Abstract

AIM: To investigate the relationship between the economy and the adult prevalence of fatty liver disease (FLD) in mainland China.

METHODS: Literature searches on the PubMed and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure databases were performed to identify eligible studies published before July 2014. Records were limited to cross-sectional surveys or baseline surveys of longitudinal studies that reported the adult prevalence of FLD and recruited subjects from the general population or community. The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was chosen to assess the economic status. Multiple linear regression and Loess regression were chosen to fit the data and calculate the 95%CIs. Fitting and overfitting of the models were considered in choosing the appropriate models.

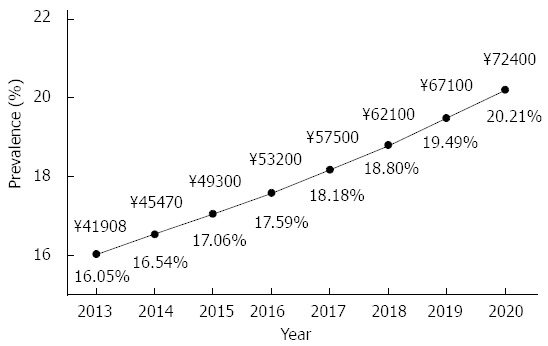

RESULTS: There were 27 population-based surveys from 26 articles included in this study. The pooled mean prevalence of FLD in China was 16.73% (95%CI: 13.92%-19.53%). The prevalence of FLD was correlated with the GDP per capita and survey years in the country (adjusted R2 = 0.8736, PGDP per capita = 0.00426, Pyears = 0.0000394), as well as in coastal areas (R2 = 0.9196, PGDP per capita = 0.00241, Pyears = 0.00281). Furthermore, males [19.28% (95%CI: 15.68%-22.88%)] presented a higher prevalence than females [14.1% (95%CI: 11.42%-16.61%), P = 0.0071], especially in coastal areas [21.82 (95%CI: 17.94%-25.71%) vs 17.01% (95%CI: 14.30%-19.89%), P = 0.0157]. Finally, the prevalence was predicted to reach 20.21% in 2020, increasing at a rate of 0.594% per year.

CONCLUSION: This study reveals a correlation between the economy and the prevalence of FLD in mainland China.

Keywords: Fatty liver disease, Epidemiology, Gross domestic product per capita, Prevalence, Economy

Core tip: The influence of the economy on the prevalence of fatty liver disease (FLD) is unclear, especially in China, which was the world’s fastest-growing major economy. In this study, a systematic review of population-based surveys was performed to explore the adult prevalence of FLD in mainland China. The gross domestic product per capita was chosen as an indicator to evaluate local economic status. Our analysis indicated that the mean prevalence of FLD in China was 16.73% and that the prevalence increased as China’s economy developed over the past 20 years. In addition, the prevalence over the next 7 years was estimated based on the current trend.

INTRODUCTION

Fatty liver disease (FLD), characterized by macrovesicular steatosis in hepatocytes, is a chronic liver disorder that can progress to hepatic cirrhosis, hepatic failure and even hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. FLD can be divided into nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD) based on the assessment of ethanol consumption[2,3]. According to the guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, NAFLD is diagnosed when ethanol consumption is less than or equal to 20 g/d in females and 30 g/d in males after the exclusion of other causes, hepatitis virus infection and of steatogenic drug administration[4]. In addition to excess alcohol intake, factors such as insulin resistance (IR), oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, immune deregulation, and adipokine release play important roles in the pathogenesis of FLD[5-7].

In the past decades, with a prevalence reaching approximately 30%, FLD has become one of the most common chronic liver disorders in industrialized Western countries[8]. It has been accepted that lifestyle changes significantly with economic development. With economic growth rates averaging 10% over the past 30 years, Westernized diet, alcoholic beverage intake and sedentary lifestyle have dramatically reshaped the pattern of Chinese daily life. The gradually growing prevalence of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome (MS) has put the Chinese population at the risk of developing FLD[9,10].

As mentioned above, the prevalence of FLD might vary with the change in lifestyle. A higher economic status tends to come with better material condition. Nevertheless, the fast pace and heavy pressure of life and work also bring problems of unhealthy diet, increased alcohol consumption and less physical exercise in the meantime. This phenomenon could have led to the diversity of FLD prevalence among the areas with different economic statuses. A limited number of studies have hypothesized that compared with developed areas, FLD is considered to be less common in underdeveloped areas[10,11]. However, the influence of the economic status on the prevalence of FLD is unclear, especially in China, which has the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

In this study, a systematic review of population-based surveys was performed to explore the adult prevalence of FLD in mainland China. By linking the prevalence to the economy, we believe that the results will be valuable to evaluate the prevalence of FLD from a novel epidemiological perspective.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategies and study inclusion

In this study, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used for the study evaluation and protocol description[12]. Literature searches on the PubMed and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases were performed to identify eligible studies published before July 10, 2014. The searches were conducted with the following terms: (fatty liver) and (prevalence or incidence or epidemic OR morbidity).

Records were limited to cross-sectional surveys or baseline surveys of longitudinal studies that offered the adult prevalence of FLD and recruited subjects from the general population or community. Additionally, surveys were included if they provided the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence based on the local population census. Convenience studies were excluded, including hospital check-up program and surveys examining adolescent or elderly or sub-groups from a specific career or race. In terms of the sample size, at least 500 adults (aged 15 years and older) were involved in each survey. If multiple studies were conducted from the same population, the authors were contacted to avoid duplication. Abstracts or unpublished data were not included.

Two investigators (Wang YM and Dai YN) performed independently the eligibility evaluation. The agreement between the two investigators was evaluated by kappa coefficient. Any disagreements on study eligibility or data extraction were resolved according to a third reviewer’s opinion (Zhu JZ).

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted according to the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guideline and the results were crosschecked[13].

If there were discrepancies in the extracted data, a consensus was reached by reviewing of the original reports and engaging in further discussion. Data were extracted to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2011 Edition for Mac; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States) and stored for further utilization. From each study, two researchers (Wang YM and Dai YN) independently extracted the information as follows: author(s), publication year, year(s) when the survey was conducted, region(s), recruitment methods, diagnosis criteria, number of subjects, age range, the prevalence in the general population and the gender-specific prevalence, if available.

Gross domestic product per capita and Chinese economic geography

The Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was chosen to assess the local economic status for the survey year. The GDP per capita information is available on the National Bureau of Statistics of China[14] website or can be acquired from the yearbooks of the local Bureau of Statistics via an internal network.

If one study was concerned with multiple cities in a province, the data of the province were considered in the analysis. Provided that the survey was performed for more than one year, the middle-year of the period was regarded as the survey year in the analysis. If an article failed to offer the precise time when the survey was conducted, the year was estimated according to the following equation: survey year = publication year - mean survey duration (2.57 years, according to the available data).

In addition, the GDP per capita in 2013-2020 was estimated according to the data from 2013, the growing rate over the past 5 years and The Twelfth Five-Year Guideline[15] approved by the National People’s Congress.

The method used to separate the interior areas from the coastal areas was referred from the Wikipedia page concerning Chinese economic geography[16].

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

All statistical tests were two-sided, and all statistical analyses were carried out with RStudio software (version 0.98.484; RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, United States). The significance level was set at 0.05. Data visualization was utilized to gain the initial distribution of the data, which allowed the authors to build models. Multiple linear regression and Loess regression were chosen to fit the data and to calculate 95%CIs. Fitting and overfitting of the models were considered in choosing appropriate models. An unpaired t-test was used to compare one value in two related samples. Associated data were plotted using RStudio software and Prism 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, United States).

RESULTS

Studies involved

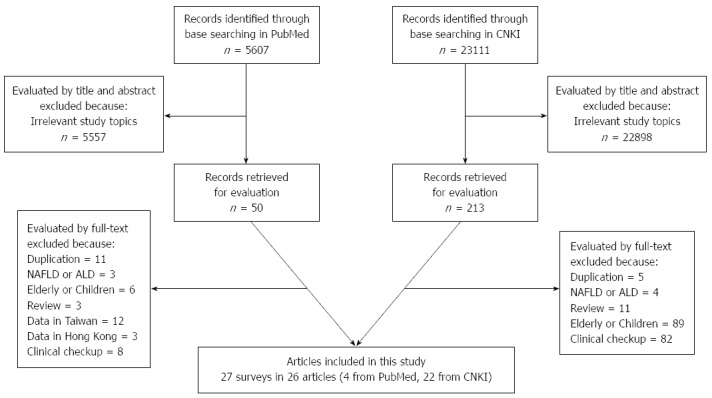

As shown in Figure 1, 5607 records on PubMed and 23111 records on CNKI were obtained from the literature search. From those, 50 articles on PubMed and 213 articles on CNKI that appeared to be relevant to the topic were identified. Finally, 27 surveys from 26 articles (4 English and 22 Chinese) were included in this study (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study evaluation process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of surveys included in the study

| Ref. | Publication year | Survey year | No. of subjects | Prevalence (%) | Male prevalence (%) | Female prevalence (%) | Cities, provinces | Recruitment methods |

| Shang et al[35] | 2004 | 2003 | 14950 | 7.85 | 9.12 | 5.41 | Handan, Hebei | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Fan et al[36] | 2005 | 2002-2003 | 3175 | 17.29 | 19.30 | 15.08 | Shanghai | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| He et al[37] | 2006 | 2001-2005 | 14069 | 17.80 | 21.70 | 10.90 | Fuoshan, Guangdong | All residents in selected communities |

| Chen et al[38] | 2006 | NA | 670 | 12.52 | 23.54 | 9.53 | Nantong, Jiangsu | All residents in selected communities |

| Peng et al[39] | 2007 | 2006 | 5313 | 9.80 | NA | NA | Shantou, Guangdong | All residents in selected communities |

| Ma et al[40] | 2007 | NA | 2043 | 13.81 | 18.55 | 14.54 | Guangdong | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Zhou et al[41] | 2007 | 2005 | 3164 | 19.09 | 21.07 | 18.03 | Guangdong | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Zhang et al[42] | 2007 | NA | 15701 | 4.80 | 5.09 | 4.21 | Guangxi | All residents in selected communities |

| Wang et al[43] | 2007 | 1995-2004 | 12247 | 22.20 | 28.10 | 13.80 | Wuhan, Hubei | All residents in selected communities |

| Tang et al[44] | 2007 | 2006 | 628 | 4.10 | NA | NA | Zhuzhou, Hunan | Cluster sampling |

| Luo et al[45] | 2007 | NA | 5267 | 24.20 | 30.77 | 17.32 | Shaoyang, Hunan | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Huang et al[46] | 2007 | 2005 | 1495 | 16.76 | 19.90 | 10.20 | Nantong, Jiangsu | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Shi et al[47] | 2007 | NA | 5703 | 3.50 | NA | NA | Shenyang, Liaoning | Cluster sampling |

| Yan et al[48] | 2007 | 2005 | 1500 | 16.46 | 20.72 | 7.34 | Shanxi/ Gansu | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Zhou et al[49] | 2009 | NA | 95567 | 19.86 | 22.37 | 17.20 | Ningbo, Zhejiang | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Yu[50] | 2010 | 2008 | 14739 | 14.97 | 11.60 | 18.25 | Nanjing, Jiangsu | All residents in selected communities |

| Yi[51] | 2011 | NA | 669 | 9.26 | NA | NA | Jiangmen, Guangdong | All residents in selected communities |

| Zhang et al[52] | 2011 | 2010 | 1116 | 15.68 | 19.07 | 14.15 | Dongguan, Guangdong | All residents in selected communities |

| Lu et al[53] | 2011 | 2009-2010 | 502 | 16.40 | 18.30 | 14.85 | Guangzhou, Guangdong | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Qu et al[54] | 2011 | 2008 | 9871 | 7.22 | 7.86 | 6.55 | Yichang, Hubei | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Shi et al[55] | 2011 | 2007 | 3815 | 19.06 | 19.31 | 19.18 | Changchun, Jilin | Random sampling |

| Zheng et al[56] | 2011 | 2008 | 1872 | 11.96 | 14.58 | 10.26 | Wenzhou, Zhejiang | Cluster sampling |

| Qin et al[57] | 2012 | 2011 | 3017 | 21.25 | 24.53 | 20.40 | Shanghai | Cluster sampling |

| Yan et al[58] | 2013 | NA | 3762 | 35.10 | 45.30 | 30.00 | Beijing | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Pan et al[59] | 2014 | 2012-2013 | 800 | 21.00 | 26.75 | 15.06 | Guangzhou, Guangdong | Random multistage stratification and cluster sampling |

| Zhou[60] | 2014 | 2008 | 6129 | 20.54 | 20.11 | 20.86 | Shanghai | All residents in selected communities |

| Zhou[60] | 2014 | 2012 | 6298 | 22.39 | 25.05 | 20.47 | Shanghai | All residents in selected communities |

NA: Not applicable.

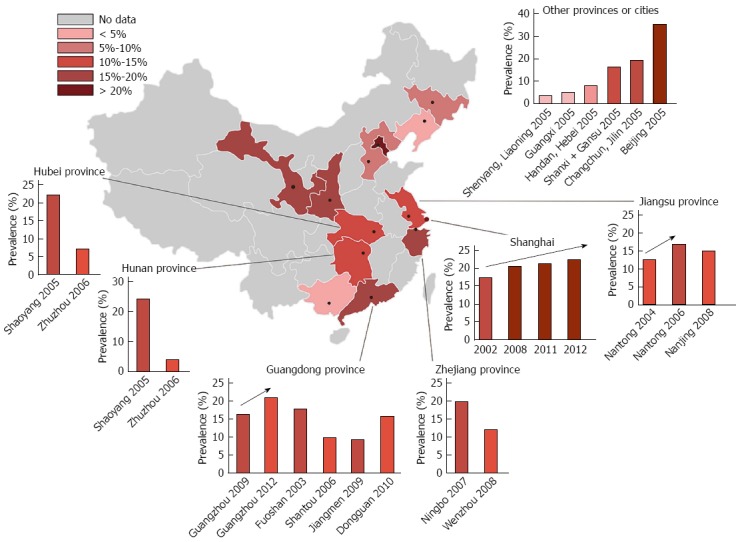

Table 2 and Figure 2 show that according to geography, there were 8 surveys conducted in the interior areas and 19 in the coastal areas. Additionally, 23 surveys presented data concerning the prevalence in males and females.

Table 2.

Pooled prevalences and correlation analyses

| No. of studies | Weighted mean prevalence (%) | Lower-upper 95%CI (%) |

Correlations between prevalence, survey years and GDP per capita |

||||

| Adjusted R2 |

P value |

Equations | |||||

| GDP per capita | Survey years | ||||||

| Mainland China | 27 | 16.73 | 13.92-19.53 | 0.8736 | 0.00426 | 0.0000394 | Prevalence = 0.0001352 x GDP per capita + 0.005158 x year |

| Region | |||||||

| Interior areas | 8 | 11.931 | 5.11-18.74 | 0.7150 | NA | 0.0025100 | Prevalence = 0.006601 x year |

| Coastal areas | 19 | 18.531 | 15.37-21.68 | 0.9196 | 0.00241 | 0.0028100 | Prevalence = 0.0001591 x GDP per capita + 0.004391 x year |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 23 | 14.012 | 11.42-16.61 | 0.9110 | 0.000808 | 0.0000554 | Prevalence = 0.0001333 x GDP per capita + 0.004394 x year |

| Male | 23 | 19.282 | 15.68-22.88 | 0.8741 | 0.066800 | 0.0000248 | Prevalence = 0.0001108 x GDP per capita + 0.007886 x year |

| Region + Gender | |||||||

| Females in interior areas | 7 | 9.293 | 3.65-14.94 | 0.7394 | NA | 0.0038200 | Prevalence = 0.00526 x year |

| Females in coastal areas | 16 | 17.1034 | 14.30-19.89 | 0.9397 | 0.008230 | 0.0017300 | Prevalence = 0.0001243 x GDP per capita + 0.0047037 x year |

| Males in interior areas | 7 | 13.92 | 4.53-23.31 | 0.7330 | NA | 0.0041200 | Prevalence = 0.008618 x year |

| Males in coastal areas | 16 | 21.824 | 17.94-25.71 | 0.9132 | 0.096440 | 0.0015600 | Prevalence = 0.0001172 x GDP per capita + 0.007758 x year |

The P-value is 0.2420, interior vs coastal areas;

The P-value is 0.0071, female vs male;

The P-value is 0.0329, female: interior areas vs coastal areas;

The P-value is 0.0157, coastal areas: female vs male. NA: Not applicable.

Figure 2.

Prevalence in China.

The diagnostic criteria mainly included the guidelines established by the Chinese Medical Association (11 surveys using the 2002 Edition[17,18], 5 surveys using the 2006 Edition[19,20], and 1 survey using the 2010 Edition[21,22], Table 3). Furthermore, all of the surveys chose ultrasound as the diagnostic tool. The recruitment methods used in these surveys primarily comprised random multistage stratification and cluster sampling (Table 1). In additional, agreement between the researchers for the evaluation of study eligibility was excellent (kappa statistic, 0.893).

Table 3.

Characteristics of surveys included in the study

| Ref. | Publication year | Survey year | Years in analysis | GDP per capita (Yuan) | Diagnosis criteria | Ages of subjects |

| Shi et al | 2007 | NA | 2005 | 29985 | NA | 18 |

| Tang et al | 2007 | 2006 | 2006 | 16526 | Self-defined | 18 |

| Zhang et al | 2007 | NA | 2006 | 8762 | NA | 20 |

| Qu et al | 2011 | 2008 | 2008 | 25445 | Standards of Ultrasonic Medicine (Chunzheng Wang, 2006, People's Medical Publishing House) | 35-74 |

| Shang et al | 2004 | 2003 | 2003 | 8936 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | NA |

| Yi et al | 2011 | NA | 2009 | 32484 | 6th Chinese Academic Materials, People's Medical Publishing House | 18 |

| Peng et al | 2007 | 2006 | 2006 | 14956 | Ultrasonic Medicine (Yong-Chang Zhou, 2006, Scientific and Technical Documentation Press) | NA |

| Zheng et al | 2011 | 2008 | 2008 | 31555 | Chinese Medical Association, 2006 Guideline | 18 |

| Chen et al | 2006 | NA | 2004 | 15806 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 20 |

| Ma et al | 2007 | NA | 2005 | 41166 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 18 |

| Yu et al | 2010 | 2008 | 2008 | 49744 | Ultrasonic Medicine (Yong-Chang Zhou, 2006, Scientific and Technical Documentation Press) | 20 |

| Zhang et al | 2011 | 2010 | 2010 | 51653 | NA | NA |

| Lu et al | 2011 | 2009-2010 | 2009 | 79383 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 18 |

| Yan et al | 2007 | 2005 | 2005 | 14847 | Chinese Medical Association, 2006 Guideline | 18-81 |

| Huang et al | 2007 | 2005 | 2005 | 19061 | Chinese Medical Association Guideline, unknown year | NA |

| Fan et al | 2005 | 2002-2003 | 2002 | 33958 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 16 |

| He et al | 2006 | 2001-2005 | 2003 | 28162 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 16 |

| Shi et al | 2011 | 2007 | 2007 | 28131 | Chinese Medical Association, 2006 Guideline | 18 |

| Zhou et al | 2007 | 2005 | 2005 | 41166 | Chinese Medical Association, 2006 Guideline | 18 |

| Zhou et al | 2009 | NA | 2007 | 61032 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 18 |

| Zhou et al | 2014 | 2008 | 2008 | 66932 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 35 |

| Pan et al | 2014 | 2012-2013 | 2012 | 106909 | Self-defined | 20 |

| Qin et al | 2012 | 2011 | 2011 | 82560 | Chinese Medical Association, 2010 Guideline | 40-70 |

| Wang et al | 2007 | 1995-2004 | 1999 | 14751 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 18 |

| Zhou et al | 2014 | 2012 | 2012 | 85373 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 35 |

| Luo et al | 2007 | NA | 2005 | 5439 | Chinese Medical Association, 2002 Guideline | 18 |

| Yan et al | 2013 | NA | 2011 | 80394 | Chinese Medical Association, 2006 Guideline | 20 |

NA: Not applicable.

Prevalence

Mainland China: As indicated in Table 2, the mean prevalence of FLD in mainland China was 16.73% (95%CI: 13.92%-19.53%).

Region

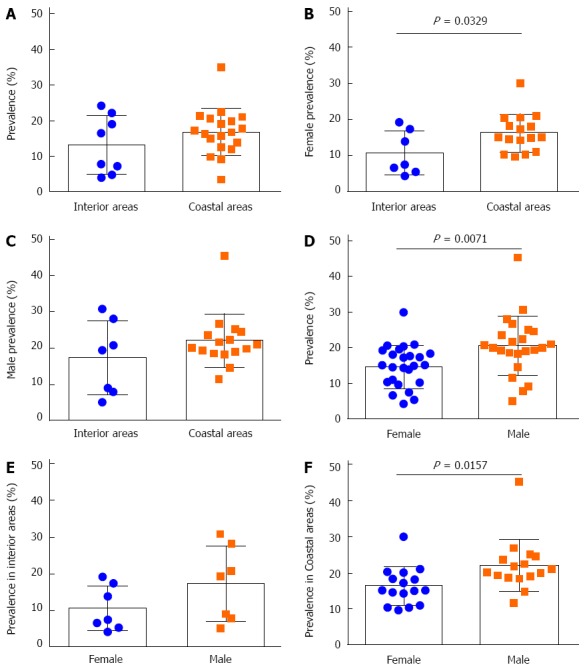

The prevalence of FLD was 11.93% (95%CI: 5.11%-18.74%) in the interior areas, while it was 18.53% (95%CI: 15.37%-21.68%) in the coastal areas. No apparent difference was found in the general prevalence between the two areas (P = 0.2420, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Comparisons of the prevalence of fatty liver disease according to gender and region. A: All: Interior areas vs coastal areas; B: Females: interior areas vs coastal areas; C: Males: interior areas vs coastal areas; D: All: females vs males; E: Interior areas: females vs males; F: Coastal areas: females vs males.

Gender

In terms of gender, the mean prevalence was 14.1% (95%CI: 11.42%-16.61%) in females, whereas it was 19.28% (95%CI: 15.68%-22.88%) in males, which was significantly higher than the female prevalence (P = 0.0071, Figure 3D).

Cross-comparisons between gender and region

In the interior areas, the prevalence of FLD between males [13.92% (95%CI: 4.53%-23.31%)] and females [9.29% (95%CI: 3.65%-14.94%)] showed no difference (P = 0.1584, Figure 3E). By contrast, in the coastal areas, males [21.82% (95%CI: 17.94%-25.71%)] presented a higher prevalence of FLD than females [17.01% (95%CI: 14.30%-19.89%)] (P = 0.0157, Figure 3F). Furthermore, the prevalence of FLD in females in the interior areas was lower than that in the coastal areas (P = 0.0329, Figure 3B).

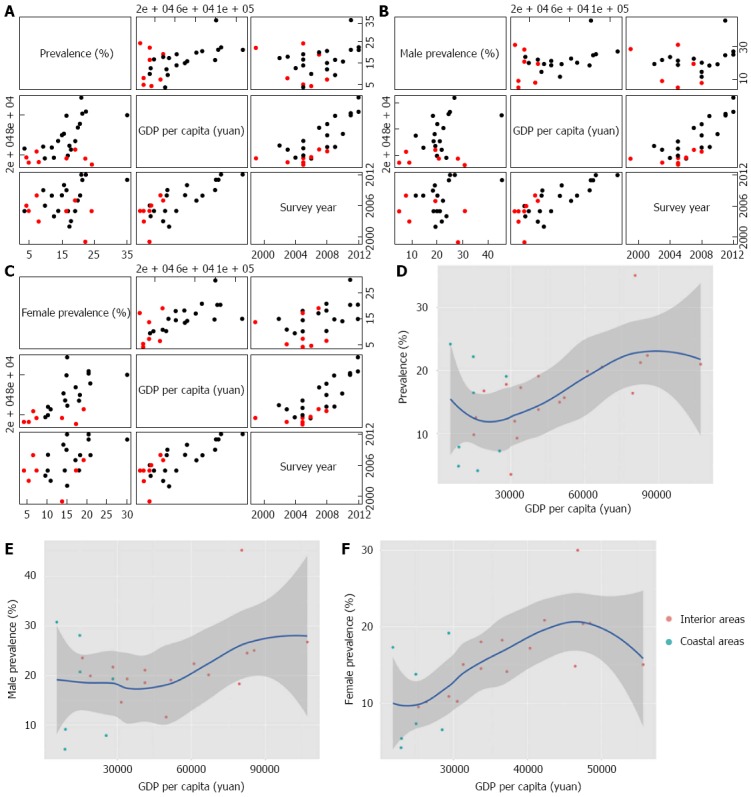

Correlations

General: A significant correlation of the prevalence of FLD with GDP per capita and survey years was detected (R2 = 0.8736, PGDP per capita = 0.00426, Pyears = 0.0000394, Figure 4A and Table 2).

Figure 4.

Correlations of the prevalence with the gross domestic product per capita and survey years. A: The general prevalence; B: The prevalence in males; C: The prevalence in females (Black spots: Studies in coastal areas; Red spots: Studies in interior areas). Survey years and changes of the prevalence according to the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita; D: The general prevalence; E: The prevalence in males; F: The prevalence in females (Red spots: Studies in coastal areas; Green spots: Studies in interior areas).

Region: Although the prevalence of FLD correlated with the survey years (R2 = 0.715, P = 0.00251), the interior areas failed to present a correlation of the prevalence with the GDP per capita. Interestingly, in the coastal areas, a correlation of the prevalence of FLD with the GDP per capita and survey years was observed (R2 = 0.9196, PGDP per capita = 0.00241, Pyears = 0.00281, Figure 4A and Table 2).

Gender: Twenty-three surveys provided the prevalence of FLD by gender and indicated the correlation of the prevalence with GDP per capita and survey years in females (R2 = 0.911, PGDP per capita = 0.000808, Pyears = 0.0000554, Figure 4C and Table 2). However, the prevalence of FLD in males failed to correlate with the GDP per capita (R2 = 0.8741, PGDP per capita = 0.0668, Pyears = 0.0000248, Figure 4B and Table 2).

Cross-analyses between gender and location: In Table 2, the interior areas presented correlations only between the survey year and the prevalence of FLD in males (R2 = 0.733, P = 0.00412) and females (R2 = 0.7394, P = 0.00382), individually. By contrast, in the coastal areas, a correlation of the female FLD prevalence with the GDP per capita and survey years was observed (R2 = 0.9397, PGDP per capita = 0.00823, Pyears = 0.00173, Table 2). However, the prevalence did not seem to correlate with the GDP per capita for males (R2 = 0.9132, PGDP per capita = 0.09644, Pyears = 0.00156, Table 2).

Trend of the prevalence

General trends: As shown in Figure 4D, the general prevalence of FLD increased along with the GDP per capita in mainland China, although two slight decreases were observed in two ranges (GDP per capita < 30000 Yuan and GDP per capita > 90000 Yuan). Regarding gender, the prevalence of FLD in males increased steadily (Figure 4E), whereas the trend of the prevalence in females dropped remarkably, after the time when GDP per capita reached approximately 8000 yuan (Figure 4F).

Trends in cities: Figure 2 displays the multiple surveys conducted in Shanghai (2002, 2008, 2011 and 2012), Nantong (2004 and 2005) and Guangzhou (2009 and 2012). It was evident that all of the three cities witnessed an upward trend of the FLD prevalence in the past decade. Specifically, the prevalence in Shanghai was 17.29% in 2002, which increased to 20.54% in 2008 and 21.25% in 2011, and reached 22.39% in 2012.

Prevalence from 2013 to 2020

Given the equation of the GDP per capita, survey years and prevalence obtained by regression analysis (Prevalence = 0.0001352 x GDP per capita + 0.005158 x year) in Table 2, the prevalence of FLD in China from 2013 to 2020 was estimated (Figure 5). Based on this calculation, the prevalence will stably increase at a rate of 0.594% per year to 20.21% by 2020.

Figure 5.

Estimated prevalence of fatty liver disease from 2013 to 2020, based on the current trend.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that the weighted mean prevalence of FLD in mainland China was 16.73%. The correlation of the prevalence with the GDP per capita and survey years demonstrated that the prevalence of FLD in China increased along with China’s economic development in the past 20 years.

After the United States, China has the second largest economy in the world by the nominal GDP and by purchasing power parity. It is the world’s fastest-growing major economy, with growth rates averaging 10% over the past 30 years. It is well known that the coastal areas have obtained the highest benefit for the recent development of the Chinese economy. By contrast, the interior areas tend to be regarded as the less well-developed areas.

Population aging, urbanization, Westernized diet, increased alcoholic beverage consumption, and sedentary lifestyle, along with a consequent obesity and diabetes epidemic, have probably led to the rapid increase in the FLD burden in the Chinese population[10]. The Chinese dietary structure has recently changed, with traditional Chinese food being replaced by foods that are higher in fat, sugar, and salt. Owing to the rapid rate of urbanization, the Chinese lifestyle is experiencing a series of changes, including a reduction in physical activity.

Given this background, obesity and MS have drawn widespread concern. It had been confirmed that obesity predisposes the individuals to the development of both ALD[23] and NAFLD[24], whereas the latter has been recognized as the liver manifestation of MS[25]. Popkin et al[26] reported a difference in the association between the socioeconomic status and obesity in rural and urban areas in China in 1993. Another study by Li et al[27] suggested that the pooled prevalence of NAFLD in the northern part of China is higher than in the southern part (21.87% and 18.21%, respectively). A national survey concerning the diabetes prevalence in China by Yang et al[28] revealed that there was a remarkable upward trend of the prevalence of diabetes in China, increasing from 2.5%[29] in 1994 to 5.5%[30] in 2001 and reaching 9.7% in 2008. This study also suggested that the level of economic development and the associated lifestyle and diet might explain the differences in the prevalence of diabetes between persons living in urban settings and those living in rural areas. There can be little doubt that the risks for the development and progression of ALD are increasing as the intake of alcohol increases[31,32]. China witnessed a consistent upward trend of recorded alcohol consumption per capita between 2000 and 2010, according to Global Information System on Alcohol and Health[33]. The previous studies have also revealed a male predominance in the prevalence of NAFLD. A previous meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of NAFLD in males was almost two times that of females[27]. A possible reason for this is the difference in hormonal regulation between males and females[34].

In this study, the prevalence of FLD was confirmed to correlate with the GDP per capita and survey years in mainland China and in the coastal areas. In contrast, the prevalence in the interior failed to correlate with the GDP per capita. Additionally, the prevalence between the interior areas and the coastal areas failed to present a difference. The two negative results probably stemmed from the notable diversity among the studies in the interior. The results above demonstrated that the prevalence of FLD in mainland China increased as the economy developed, especially in the coastal areas.

Regarding gender, males presented a higher prevalence than females in mainland China and in the coastal areas. Furthermore, the prevalence of FLD in females in the interior was lower than that in the coastal areas. Interestingly, the female FLD prevalence correlated with the GDP per capita and survey years within the country and in the coastal areas.

Shanghai, the largest city and the commercial and financial center of China, displayed a steadily rising trend of the FLD prevalence from 2002 to 2012. Correspondingly, the similar rise was observed in Guangzhou and Nantong, two well-developed cities in the coastal areas. Additionally, based on the current trend, the prevalence of FLD in China was predicted to reach 20.21% in 2020, increasing at a rate of 0.594% per year.

This study has several strengths. First, the GDP per capita was chosen as an indicator to evaluate the local economic status. In additional, considering the diversity of the economy and environment, 22 cities and 2 provinces were divided into two groups, the interior and the coastal. Finally, the prevalence over the next 7 years was estimated based on the current trend.

In terms of weaknesses, first, this study failed to compare the rural and the urban areas, owing to a lack of GDP per capita. Second, there were several factors that were difficult to detect, including ethnic, dietary or cultural disparities among areas. Moreover, although ALD and NAFLD differ in a series of characteristics, ranging from differences in clinical features to patient outcomes, this study failed to separately process the two prevalences because most Chinese records only offered FLD data, not separated data. Finally, the numbers of studies from the interior and the coastal areas were clearly imbalanced. More studies reporting the prevalence in the west and the central areas are required.

In conclusion, this is the first study to explore the relationship between the economy and the prevalence of FLD in mainland China. This study demonstrated that the prevalence increased as the GDP per capita grew over the past 20 years, especially in the coastal areas. In addition, males presented a higher prevalence than females in the country and in the coastal areas in particular. We believed that this study suggests a symbiotic correlation between the prevalence of FLD and the economy, offering a novel epidemiologic perspective on the global situation of FLD.

COMMENTS

Background

A limited number of studies have hypothesized that compared with developed areas, fatty liver disease is considered to be less common in underdeveloped areas. However, the influence of the economic status on the prevalence of fatty liver disease is unclear, especially in China, which has the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

Research frontiers

With the remarkable economic development in the past decades, population aging, urbanization, Westernized diet, increased alcoholic beverage consumption, and sedentary lifestyle probably contributed to the rapid increase of fatty liver disease in China.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study revealed that the weighted mean prevalence of fatty liver disease (FLD) in mainland China was 16.73%. Furthermore, the correlation of the prevalence with the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and survey years demonstrated that the prevalence of FLD in China increased with the development of China’s economy over the past 20 years.

Applications

This study suggested a symbiotic correlation between the prevalence of FLD and the economy, offering a novel epidemiologic perspective on the global status of FLD. However, more studies reporting the prevalence in the west and the central areas of China are required.

Terminology

The GDP is the total market value of all of the final products and services produced during a specific time period in a country. It is considered to be the foremost parameter of the standard of living of a country. The GDP per capita is an indicator used by many countries to indicate the overall growth and development of a country. It is calculated by dividing the GDP by the population of the country. It is studied under macroeconomics and is related to national accounts.

Peer-review

Authors evaluated association between prevalence of FLD and GDP in China by using published articles from 2007 to 2014. Then they made a projection for the prevalence of FLD in 2020 if GDP continues to increase steadily.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: All authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: November 18, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Article in press: February 11, 2015

P- Reviewer: Abenavoli L, Balaban YH, Iwasaki Y, Lonardo A, Wu J S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohapatra S, Patra J, Popova S, Duhig A, Rehm J. Social cost of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence in high-income countries. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn W, Angulo P, Sanderson S, Jamil LH, Stadheim L, Rosen C, Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Shah VH. Utility of a new model to diagnose an alcohol basis for steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1057–1063. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nascimbeni F, Pais R, Bellentani S, Day CP, Ratziu V, Loria P, Lonardo A. From NAFLD in clinical practice to answers from guidelines. J Hepatol. 2013;59:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol. 2004;34:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machado M, Cortez-Pinto H. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:637–642. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000241677.40170.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. Management of fatty liver disease with the metabolic syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:487–500. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.903798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amarapurkar DN, Hashimoto E, Lesmana LA, Sollano JD, Chen PJ, Goh KL. How common is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region and are there local differences? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:788–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan JG. Epidemiology of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28 Suppl 1:11–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan JG, Farrell GC. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Hepatol. 2009;50:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Bureau of Statistics of China. Data of GDP per capita. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/

- 15.Wikipedia. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan of The People Republic of China. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five-year_plans_of_the_People’s_Republic_of_China.

- 16.Wikipedia. Geography of China, Economic geography. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_China - Economic_geography.

- 17.Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease Study Group, Chinese Liver Disease Association. [Diagnostic criteria of alcoholic liver disease] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2003;11:72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease Study Group of Chinese Liver Disease Association. [Diagnostic criteria of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2003;11:71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease Study Group of the Chinese Liver Disease Association. [Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2006;14:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng MD, Li YM, Chen CW, Lu LG, Fan JG, Wang BY, Mao YM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of alcoholic liver disease. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:113–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan JG, Jia JD, Li YM, Wang BY, Lu LG, Shi JP, Chan LY. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: update 2010: (published in Chinese on Chinese Journal of Hepatology 2010; 18: 163-166) J Dig Dis. 2011;12:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YM, Fan JG, Wang BY, Lu LG, Shi JP, Niu JQ, Shen W. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of alcoholic liver disease: update 2010: (published in Chinese on Chinese Journal of Hepatology 2010; 18: 167-170) J Dig Dis. 2011;12:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108–111. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazo M, Hernaez R, Eberhardt MS, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Guallar E, Koteish A, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:38–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, Melchionda N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003;37:917–923. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popkin BM, Keyou G, Zhai F, Guo X, Ma H, Zohoori N. The nutrition transition in China: a cross-sectional analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993;47:333–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Xue J, Chen P, Chen L, Yan S, Liu L. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mainland of China: a meta-analysis of published studies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:42–51. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, Shan Z, Liu J, Tian H, Ji Q, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1090–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan XR, Yang WY, Li GW, Liu J. Prevalence of diabetes and its risk factors in China, 1994. National Diabetes Prevention and Control Cooperative Group. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1664–1669. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.11.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu D, Reynolds K, Duan X, Xin X, Chen J, Wu X, Mo J, Whelton PK, He J. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the Chinese adult population: International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterASIA) Diabetologia. 2003;46:1190–1198. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toshikuni N, Tsutsumi M, Arisawa T. Clinical differences between alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8393–8406. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellentani S, Saccoccio G, Costa G, Tiribelli C, Manenti F, Sodde M, Saveria Crocè L, Sasso F, Pozzato G, Cristianini G, et al. Drinking habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol induced liver damage. The Dionysos Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:845–850. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Global Information System on Alcohol and Health. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/alcohol/en/

- 34.Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, Van Pelt RE, Wang H, Eckel RH. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang J, Li Y, Xu B, Liu L, Li Z, Zhang F. The analysis of the prevalence of fatty liver and the related factors. Zhonghua Quake Yixue Zazhi. 2004;7:1409–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan JG, Zhu J, Li XJ, Chen L, Li L, Dai F, Li F, Chen SY. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in a general population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol. 2005;43:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He W, Gao J, Tang F, Huang W, Chen J, Ouyang S. The epidemiology investigation of adult fatty liver in Ronggui and its integrating intervention. Xiandai Yiyuan. 2006;6:123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen YX, Yu XS, Jiang JH, Huang PX, Shi JH. The prevalence of fatty liver in individuals in suburbs of Haimen city. Shiyong Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2006;9:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Y, Xie DM. The analysis of the result of B-ultrasonic examination of 5313 community people. Lvxing Yixue Kexue. 2007;13:34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma JX, Zhou YJ, Chen PY, Nie YQ, Shi SL, Li YY. Epidemiological survey on fatty liver in rural area of Guangdong province. Zhongguo Gonggong Weisheng. 2007;23:874–876. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou YJ, Li YY, Nie YQ, Ma JX, Lu LG, Shi SL, Chen MH, Hu PJ. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and its risk factors in the population of South China. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6419–6424. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang C, Huang T, Yu J, Li J, He Z, Zhou D, Ye S, Deng W, Sheng Y, Zhai H, et al. Analysis of incidence of hepatic diseases in population of anti-cancer screening and HBsAg positives in rural areas of Guangxi. Zhongguo Redai Yixue. 2007;7:1316–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Xia B, Ma C, Hu Z, Chen X, Cao P. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in the Shuiguohu district of Wuhan city, central China. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:192–195. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.052258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang XY. 628 community inhabitant healthy physical examination situation analyzes. Zhongguo Mingkang Yixue. 2007;19:163–164. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo ZX, Zhang GH, Chen JY, Wang XD, Liu HW, Si JM. Epidemiological survey of prevalence cholelithiasis and its risk factors in a general adult population of Shaoyang. Xiandai Xiaohua and Jieru Zhenliao. 2007;12:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang W, Shi F. The Prevalence of Fatty Liver among the Residents of Nantong City and Relevant Factors. Zhiye and Jiankang. 2007;23:115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi XW. Investigation and analysis on chronic diseases correlation and factors of community inhabitants in Shenyang. Xiandai Yufang Yixue. 2007;34:2313–2315. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan H, Lu X, Luo J, Zhou X. Epidemiological analysis of alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver in Shanxi and Gansu province. Zhongguo Weichangbingxue and Ganzangbingxue Zazhi. 2007;16:347–353. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou J, Tong Y, Lv Q, Yu J, Li Y, Ding Q. Epidemiological survey of prevalence of fatty liver and its risk factors in a general adult population of Fenghua. Zhongguo Ganbing Zazhi. 2009;1:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu L. The report concerning the prevalence of fatty liver among the residents in Yongyang, Lishui. Heilongjiang Yixue Zazhi. 2010;32:950–951. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yi W. The analysis of rural residents check-up in Tangxia, Jiangmen. Jilin Yixue. 2011;32:4386–4387. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, Wang Q, Zhou L, Cai C, Mo X, Gao F, Liang C. Analysis of residents check-up in Zhangluo Community, Dongguan. Shequ Yixue Zazhi. 2011;9:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu Y, Yao J, Zhi M, Hu Q. The adult prevalence of fatty liver and the related factors in Jiawan, Guangdong. Shiyong Yixue Zazhi. 2011;27:3589–3591. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qu Y, Liang X, Dong Y, Qu K. The epidemiology of fatty liver among rural residents and the risk factors in Yiling, Yichang. Shequ Yixue Zazhi. 2011;9:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi X, Wei Q, He S, Tao Y, Sun J, Niu J. Epidemiology and analysis on risk factors of non-infectious chronic diseases in adults in northeast China. Jilin Dazue Xuebao. 2011;37:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng J, Chen P, Xie J. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in community residents. Zhonghua Yufang Yixue Zazhi. 2011;12:152–154. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qin L, Su Q, Gu H, Lu S, Jian W. Epidemiological survey of prevalence of fatty liver and its risk factors in adult population of Chongming district, Shanghai. Neike Lilun Yu Shijian. 2012;7:280–283. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan J, Xie W, Ou WN, Zhao H, Wang SY, Wang JH, Wang Q, Yang YY, Feng X, Cheng J. Epidemiological survey and risk factor analysis of fatty liver disease of adult residents, Beijing, China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1654–1659. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan Y, Lao R, Chen T. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in community population. Zhonguo Yiyao Daobao. 2014;11:108–110. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou L. The prevalence of fatty liver disease among the citizens older than 35 in Shanghai of 2008 and 2012. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2014;19:204–205. [Google Scholar]