Abstract

The perplexing mystery of why so many trephined skulls from the Neolithic period have been uncovered all over the world representing attempts at primitive cranial surgery is discussed. More than 1500 trephined skulls have been uncovered throughout the world, from Europe and Scandinavia to North America, from Russia and China to South America (particularly in Peru). Most reported series show that from 5-10% of all skulls found from the Neolithic period have been trephined with single or multiple skull openings of various sizes. The unifying hypothesis proposed by the late medical historian Dr. Plinio Prioreschi (1930-2014) regarding the reason for these trepanations (trephinations) is analyzed. It is concluded that Dr. Prioreschi's cohesive explanation to explain the phenomenon is valid and that his intriguing hypothesis is almost certainly correct. In the opinion of this author, the mystery within an enigma has been solved.

Keywords: History of medicine, Neolithic, primitive cranial surgery, trepanation, trephination, trephined skulls

The perplexing mystery of why so many skulls from the Neolithic period have been uncovered all over the world with trephination holes has been solved for nearly 25 years, and yet this fact has not percolated through recent surgical history. Thus uninformed, the mystery continues to perplex medical historians. For about the same period of time, the “Renaissance” physician, scientist, linguist, and medical historian, the late Plinio Prioreschi (1930–2014), M.D., Ph.D., warned physicians and surgeons of the danger of neglecting medical history and delegating the task to professional (social) historians with little or no medical or surgical knowledge.[4] Physicians, surgeons, and in this instance, neurosurgeons, although busy with their practices, research, and occupied with new surgical and technological advances, should not neglect medical and surgical history.

Returning to the subject at hand, when I wrote my series of articles on “Violence, mental illness, and the brain – A brief history of psychosurgery” (2013), I offered the conventional views on the topic of trephination in primitive medicine:

“Trephination (or trepanation) of the human skull is the oldest documented surgical procedure performed by man. Trephined skulls have been found from the Old World of Europe and Asia to the New World, particularly Peru in South America, from the Neolithic age to the very dawn of history. We can speculate why this skull surgery was performed by shamans or witch doctors, but we cannot deny that a major reason may have been to alter human behavior – in a specialty, which in the mid-20th century came to be called psychosurgery!”[1]

Following the footsteps of the renowned physician and medical historian Dr. William Osler and other conventional scholars,[8,9,11] I further stated, “Surely we can surmise that intractable headaches, epilepsy, animistic possession by evil spirits, or mental illness, expressed by errant or abnormal behavior could have been indications for surgical intervention prescribed by the shaman of the late Stone or early Bronze Age.”[1] A more recent and substantive paper from the related fields of anthropology and bioarchaeology still substantiates the conventional views of ancient cranial surgery as it relates to Peru (c. A.D. 1000–1250).[2]

I had unfortunately not read Dr. Prioreschi's seminal article, “Possible reasons for Neolithic skull trephining,”[7] in which he had in fact unraveled the mystery within an enigma of why the primitive surgeons of the Neolithic period performed trepanations and at such a high frequency. Recently, I finally had the opportunity to read the first volume on “Primitive and Ancient Medicine” of Dr. Prioreschi's monumental A History of Medicine. Thus armed, I revisited the subject and analyzed carefully the hypothesis propounded by Dr. Prioreschi.[5,6,7]

Prioreschi had extensively reviewed surgical history and found no cohesive explanation for the phenomenon. Spurred by the unsolved mystery, he applied the deductive reasoning of the celebrated but fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes (created by another physician and author, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle), to the task and arrived to the logical explanation that follows. Before we discuss Prioreschi's intriguing hypothesis, we should first consider some key facts related to the problem at hand.

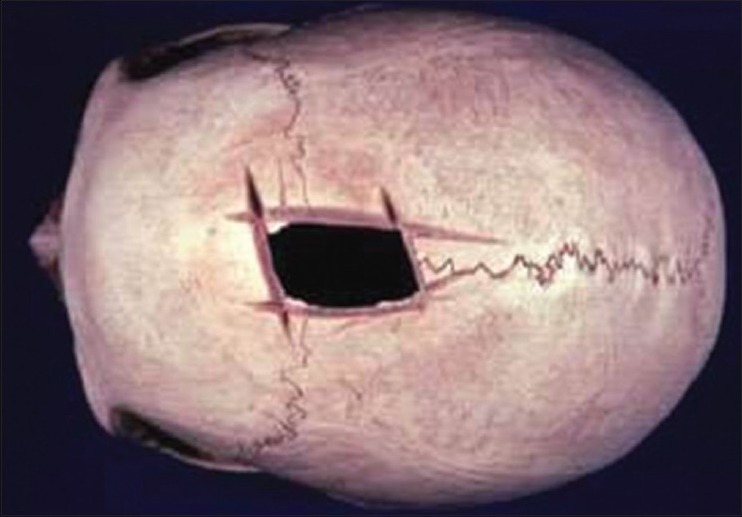

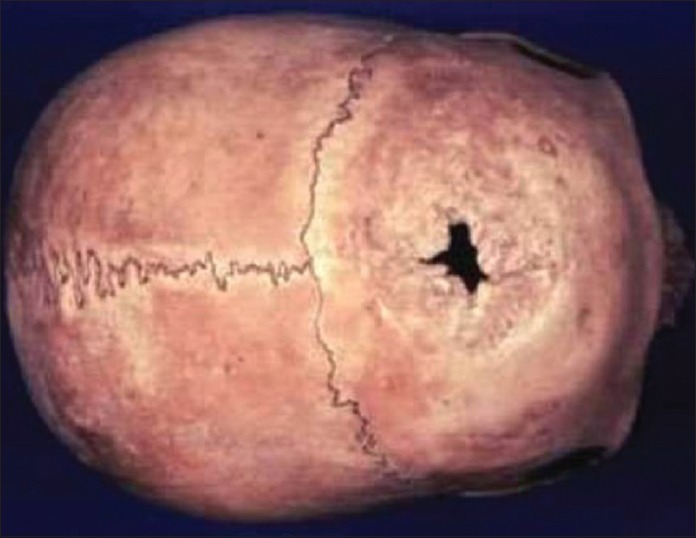

First, more than 1500 trephined skulls have been uncovered throughout the world, from Europe and Scandinavia to North America, from Russia and China to South America (particularly in Peru). Most reported series show that from 5% to 10% of all skulls (e.g., ranging from “as low as 2.5% to as high as 19%”) found from the Neolithic period have been trephined with single or multiple skull openings of various sizes.[5] Many of the skulls show evidence of fractures (i.e., half of all those discovered in South America). In some cases the operations were incomplete, as if the patients suddenly woke up and terminated the procedure. Some skull openings showed evidence of healing, meaning the patients survived the operations; others did not [Figures 1-5]. In these latter cases it is impossible to determine if the patients were already (or recently) dead or whether the patients died soon after the procedure. Trepanations (or trephinations) were performed in children as well as adults and in both males and females. The majority of trephinations, though, have been found in adult males. A variety of techniques were utilized for trephining worldwide, including scrapping, cutting, and both straight and curved grooving of the skull. The dura mater, we suspect, was not penetrated. Although claims have been made by some paleopathologists (and more recently bioarchaelogists) to the effect – namely, that they can ascertain whether patients were recently dead or had died soon after (or during the procedure) by examination of the beveled edges of the trephined skull[2] – this determination in most cases cannot be made convincingly or with any degree of certainty.[3,5,10] The criteria used by these researchers to attempt to make this determination, in fact, have been proved to be unreliable.[3,10] This fact should be stated because some of the previously entertained reasons (including my own ideas formerly maintained) determined the posited reasons for the trepanations. As noted above in my own citation, the reasons for trepanation were many, revolving on various themes. At least one or more reasons depended on whether the patient was alive (i.e., as to effect either a supernaturalistic or naturalistic surgical treatment) or dead (i.e., as a supernaturalistic magical ritual or merely to procure skull fragments as amulets) at the time of the trepanation.

Figure 1.

Prehistoric adult female cranium from San Damian, Peru (unhealed trepanation). Courtesy of the San Diego Museum of Man and their publication entitled Trephined Skulls; published in 1980

Figure 5.

Prehistoric human skull with multiple trepanations, including incomplete trephinations, from Monte Albán, Mexico, Museo del Sitio. Courtesy of Medical News Today, Prehistoric Medicine, MediLexicon International Ltd

Figure 2.

Prehistoric adult female cranium from Cinco Cerros, Peru (unhealed trepanation). Courtesy of the San Diego Museum of Man and their publication entitled Trephined Skulls; published in 1980

Figure 3.

Prehistoric adult male cranium from Cinco Cerros, Peru (healed trephination). Courtesy of the San Diego Museum of Man and their publication entitled Trephined Skulls; published in 1980

Figure 4.

Section of prehistoric human skull with incomplete trepanation, c. A.D. 1000-1250. Skulls from excavated burial caves in the south-central province of Andahuaylas in the Andes, Peru. Courtesy of The Current, University of California at Santa Barbara. Photo credit: Danielle Kurin

Second, Prioreschi pointed out important additional facts. Neolithic man was a hunter and his life experience revolved around this activity. Cave dwelling paintings also testify to this phenomenon. Consequently, he was very aware of hunting and war injuries. Neolithic man noticed, for example, that penetrating injuries to the chest and abdomen were usually fatal to man and animal. Likewise, massive blunt head injuries were invariably lethal. Nevertheless, blunt injuries to the head, if not massive, were not invariably fatal. With mild blows to the head, man or animal could be knocked down briefly and then get up and run. At other times, a man could be left for “dead” in the back of the cave, but after a period of time, he could “miraculously” recover and become “undead.” It was only with head injuries that primitive man noted that this phenomenon took place – namely suddenly becoming “dead” after an injury and then “undead.” Or, as we would describe it, that a head injury caused a momentary loss of consciousness (LOC), as in a concussion, or a more prolonged LOC, as in a cerebral or brainstem contusion – and then recover as the cerebral edema subsided and neural circuits were reestablished. Of course, primitive man did not understand the pathophysiology involved. For the Stone Age man, there was also no awareness of the inevitability of death and no recognized mortality as part and parcel of the human condition. Diseases, pain and suffering, and death took place as a result of sorcery, evil spirits, or some other supernaturalistic intervention. People could become gradually “dead” from an illness or injury and then become “undead” because of some phenomenon. In the case of injuries, these conditions were caused by observed specific events, such as penetrating injuries or serious blows. These occurrences did not occur randomly. Such was also the case with becoming “dead” and “undead,” and the primitive surgeon of Neolithic times understandably reasoned that he could also do something to bring back to life those individuals essential to the survival of the group.[6]

Observing that small injuries to the head, more frequently than other injuries, resulted in “dying” (i.e., LOC with a concussion or a contusion resulting in coma) and “undying” (i.e., spontaneous recovery), they must, according to Prioreschi, come to believe that “something in the head had to do with undying.”[5,6] More blows would not accomplish the ritual, but an opening in the head, trephination, could be “the activating element,” the act that could allow the demon to leave the body or the good spirit to enter it, for the necessary “undying” process to take place. If deities had to enter or leave the head, the opening had to be sufficiently large. Prioreschi writes: “It would appear that he was trying to recall to life people who had died (or were dying) without wounds (or with minor ones), in other words, people affected with diseases and people whose small wounds (e.g., undisplaced fractures of the skull with small lacerations of the scalp) were not so serious as to prevent “undying’;.”[6] Incomplete trepanations, as mentioned previously, are explained, not because the patients died during the procedure, but because of patients waking up and interrupting the procedure by suddenly becoming “undead.”[5,6]

The head was chosen for the procedure, not because of any particular intrinsic importance or because of magic or religious reasons, but because of the unique and universally accumulated experience observed by primitive man in the Stone Age with ubiquitous head injuries during altercations and hunting. Otherwise, the pelvic bone or femur could have served the same purpose. We must recall that even the much more advanced ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Hindu, and even Hellenic civilizations believed the heart to be the center of thought and emotions, not the brain. In fact, the association of the heart with emotions lingered to the present age.

Since most Neolithic skulls were not trephined, Prioreschi further hypothesized the procedure was reserved for the most prominent male members of the group and their families.[5,6] I believe Prioreschi's hypothesis is valid and his thesis almost certainly correct, unless new evidence proves otherwise: Man in the Stone Age all over the world indulged in the ubiquitous practice of Neolithic trepanation for bringing back to life or effect the resuscitation (the act of “undying”) of prominent members of the group who were considered “dead” by their own primitive conception of death and dying from both serious illness or injury. Trephination was an effort the primitive surgeon thought was worth making to bring back to life those prominent individuals considered essential to the survival of the group in the Neolithic phase of human social development.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2015/6/1/72/156634

REFERENCES

- 1.Faria MA. Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 1 — From trephination to lobotomy. [Last accessed 2015 Apr 11];Surg Neurol Int. 2013 4:49. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.110146. Available from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2013/4/1/49/110146 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurin DS. Trepanation in south-central Peru during the early late intermediate period (c. AD 1000–1250) Am J Phys Anthropol. 2013;152:484–94. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortner DJ, Putschar WG. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1985. Identification of pathological conditions in human skeletal remains; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prioreschi P. See my review of this book in Surg Neurol Int 2015. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995. A History of Medicine. Vol. I: Primitive and Ancient Medicine; pp. xvii–xxx. In Progress. Available from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prioreschi P. Primitive and Ancient Medicine. I. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995. A History of Medicine; pp. 21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prioreschi P. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995. A History of Medicine. Vol. I: Primitive and Ancient Medicine; pp. 30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prioreschi P. Possible reasons for Neolithic skull trephining. Perspect Biol Med. 1991;2:296–303. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1991.0028. XXXIV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rifkinson-Mann S. Cranial surgery in Peru. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:411–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robison RA, Taghva A, Liu CY, Apuzzo ML. Surgery of the mind, mood and conscious state: An idea in evolution. World Neurosurg. 2012;77:662–86. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers SL. Thomas. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C; 1985. Primitive Surgery; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker AE, editor. New York: Hafner Publishing; 1967. A History of Neurological Surgery; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]