Abstract

Despite numerous technical hurdles, the realization of true personalized medicine is becoming a progressive reality for the future of patient care. With the development of new techniques and tools to measure the genetic signature of tumors, biomarkers are increasingly being used to detect occult tumors, determine the choice of treatment and predict outcomes. Methylation of CpG islands at the promoter region of genes is a particularly exciting biomarker as it is cancer-specific. Older methods to detect methylation were cumbersome, operator-dependent and required large amounts of DNA. However, a newer technique called methylation on beads has resulted in a more uniform, streamlined and efficient assay. Furthermore, methylation on beads permits the extraction and processing of miniscule amounts of methylated tumor DNA in the peripheral blood. Such a technique may aid in the clinical detection and treatment of cancers in the future.

Keywords: biomarker, cancer detection, colon cancer, CpG island methylation, methylation on bead, pancreatic cancer, personalized medicine

Cancer diagnosis: personalized medicine as the future

Despite advances in intervention and care, cancer continues to be a leading cause of death. As cancer heterogeneity is known to be widely existent [1,2], there is a pressing need to utilize advances in genomic and epigenomic research to personalize cancer treatments. Large-scale sequencing analyses of solid cancers have identified extensive diversity between individual tumors, which may account for treatment failures. Tumor heterogeneity is evident in the randomized controlled trials performed with hundreds of patients [3]. While the majority will respond to the first-line therapies, there are always patient outliers, those who do not conform to the norm. Furthermore, such trials are cumbersome, time-consuming, costly and fail to address patients with outlier tumors. It is evident that we must tailor our detections and treatments to our patients’ needs, the so-called era of personalized medicine [4]. Identifying the genetic variants underlying each tumor phenotype and tailoring medical intervention to each individual can dramatically improve health [5,6]. We are on the cusp of new techniques and tools to measure the genetic signature of tumors, with the expectation that this signature will direct the choice of treatment and predict outcome [7]. An innovation termed methylation on beads (MOB) has permitted detection of tumor signatures in blood samples. Here, we will discuss how tumor signatures are utilized as bio-markers, the evolution of MOB and the clinical applicability of this innovative technique.

Biomarkers: avenues for personalized medicine

Personalized medicine is dependent upon bio-markers that can detect cancer, give information regarding patient prognosis and can predict response to various therapies. The greatest obstacle in personalized medicine is the identification of biomarkers that are clinically useful and can be obtained via non-invasive means. Biomarkers comprise cellular components or products that provide information about the cells from which they were derived. Biomarkers can be categorized as detection, prognostic or predictive biomarkers [8]. Detection biomarkers reveal information regarding the presence or absence of a given disease state, such as cancer. Early detection of cancers provides the best survival outcomes as patients whose cancers are caught in early stages have the best prognosis [9]. One well-known early detection biomarker is prostate-specific antigen, which permits the detection of prostate cancer at early stages, although with variable sensitivity and specificity [10].

Prognostic biomarkers offer information about a patient’s expected outcome, independent of treatment, for example, breast cancer gene-expression signatures – marketed for clinical use as Oncotype DX (Genomic Health), MammaPrint (Agendia) and the H/I test (AviaraDx) – that estimate the probability of the original breast cancer recurring after it has been resected [11,12].

Predictive biomarkers provide information as to how a patient will respond to a given type of therapy. This is highlighted in the treatment of breast cancer where chemotherapies are targeted against particular receptors based upon the presence or absence of the receptor(s) in question. If the receptor is present, the targeted drugs will be of benefit to patients, for example, patients with breast cancer in which the gene ERBB2 (also known as HER2 or NEU) is amplified (i.e., extra copies are present) benefit from treatment with trastuzumab (Herceptin), whereas when the gene encoding the estrogen receptor is expressed by the tumor, the patients respond to treatment with tamoxifen [13]. Patients lacking the receptor derive little to no benefit from treatment with the targeted chemotherapeutic agent [14].

All biomarkers, regardless of type, must meet several criteria in order to be considered useful in a clinical setting. Biomarkers should be both sensitive and specific, they must be able to detect the biomarker at physiologically relevant concentrations and they must detect the biomarker as it corresponds exclusively to the disease in question. Furthermore, biomarker assays must ultimately provide an opportunity to improve the current standard of care. It is worthy here to mention the fact that only few of the numerous biomarkers discovered so far are routinely used in the clinical setting. Technologies such as proteomics and DNA microarray studies have resulted in more than 150,000 papers documenting thousands of potential biomarkers, but fewer than 100 have been validated for routine clinical practice [15].

All biomarkers must be obtained from some type of body fluid or tissue [16,17]. In the past, most biomarkers have been obtained from the cancerous tissue itself. This poses a difficulty because the patient must undergo complicated and/or painful invasive procedure to obtain that tissue, whether it is a biopsy taken through the skin or one obtained from an endoscopic procedure. As an example, colonoscopy still remains the gold standard for the detection of colon cancer. Colonoscopy has been demonstrated to be both diagnostic and therapeutic for smaller lesions [18]. This has been well-recognized for over a decade. Patients who undergo screening are found to have smaller lesions, are able to be treated and have better outcomes compared with patients who do not undergo screening [19]. Nationwide campaigns have advertised this fact. Yet screening rates remain far below what would be considered to be ideal [20]. When this was investigated, it was found that one of the main reasons for this phenomenon was that patients did not want to undergo an invasive procedure [21].

In comparison, non-invasive methods of cancer detection may significantly improve patient compliance. These methods include collections from stool, sputum, or ideally, from blood [22–25]. Development of blood-based biomarkers has been hampered for several reasons. The detection of mutations in blood often requires long segments of free-floating DNA. The segments must be long as many genes have more than one location where base-pair mutations occur. Even in genes with a single point mutation, the DNA segments must derive from the tumor cells so as to reflect tumor-specific changes. Such free-floating, tumor-derived DNA fragments are exceedingly rare. Likewise, if detection of circulating tumor cells is the goal, this is hampered by the fact that circulating tumor cells are seldom found in the peripheral circulation, even when large volumes of blood are collected to optimize capture of circulating tumor cells [26,27].

DNA methylation: an attractive biomarker

DNA methylation is an attractive biomarker because it is cancer-specific, sensitive and because it can be obtained for testing via non-invasive methods. Specific regions within DNA contain clusters of CpG dinucleotides called CpG islands [28]. The CpG islands within the promoter regions are predominantly unmethylated in normal cells, except for some genes involved in tissue differentiation [29]. In cancer cells, these islands often develop abnormal levels of methylation, which distinguishes them quite clearly from normal cells [30]. Many assays for DNA methylation have shown excellent sensitivity and specificity for cancer, as reported in several studies [31,32]. The use of a gene panel that consists of several genes instead of single gene may give even better results [33]. Another advantage of DNA methylation as a biomarker for cancerous cells is that it occurs in a very limited region of DNA [34,35]. The benefit of these local changes is that only short segments of DNA need to be isolated to detect cancer-specific changes. Such short segments of DNA are commonly found in the blood and may be best suited to methylation-based approaches for isolation and detection [36]. This creates a situation in which blood-based assays are ideally suited for the detection of methylated DNA originating from tumor cells.

DNA methylation detection

While previous methods of DNA methylation detection typically required large amounts of tissue, newer methods have evolved that permit detection utilizing minute amounts of DNA template. Cancer-derived DNA is shed in the periphery by two means, either by direct shedding of tumor-derived DNA into nearby tissues or by apoptosis of circulating tumor cells. Detection of DNA methylation biomarkers can then be done in various bodily fluids to detect this free-floating DNA. Suitable bodily fluids for analysis include stool for colon cancers, saliva for oral and head and neck cancers, urine for urological cancers, bronchial lavage fluids for lung cancer and peripheral blood for all types of cancers [37–41].

Various techniques have been used in recent years to detect differentially methylated sequences in normal versus cancerous tissues. Early methods included the use of methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes followed by southern blotting or PCR. These methods can be very sensitive to incomplete digestion, which generates false-positive results and, furthermore, requires very large amounts of DNA [42,43]. One of the most widely used methodologies for detecting methylation from tissues is methylation-specific PCR (MSP). This process was first described in the mid-1990s and couples bisulfite treatment with a PCR-based strategy. During bisulfite treatment, ostensibly all unmethylated cytosines are converted to uracil, while all methylated cytosines remain unchanged. A primer set specific to the bisulfite-treated methylation sequencing is used to exclusively amplify methylated DNA, if present. This is compared with a primer set that amplifies the wild-type, unmethylated sequence. The products of amplification can then be run on a gel and imaged to assess the presence and degree of methylation in the sample [44].

MSP, while being quite sensitive, does have multiple drawbacks. The bisulfite modification exposes the DNA to a very harsh environment for an extended period of time and often causes extensive DNA fragmentation [45]. Furthermore, this bisulfite step typically takes 16 h to complete, causing long delays in obtaining results. MSP does not allow for quantification of the level of methylation [46]. Some have argued that low levels of methylation that appear as unmethylated by MSP may in fact be biologically significant. Finally, MSP requires running each gene individually and this can be labor-intensive and operator-dependent. These factors become critical when considering using MSP technology in a commercial laboratory assay.

Many of the difficulties with conventional MSP have since been addressed. Commercial kits available today have largely overcome the problem of DNA fragmentation and poor cytosine to uracil conversion rates. The bisulfite conversion step is now available as a 4-h treatment, which minimizes fragmentation and delays [47]. Quantitative MSP allows for quantification of the amount of methylation at each gene. This reduces the concern for minimal, but biologically significant amounts of methylation at the CpG island [43]. Quantitative MSP allows running multiple genes or samples at once, reducing labor requirements. Furthermore, it permits standardization, thus minimizing inter-operator variability. Finally, PCR-based methods remain the most cost–effective modalities as compared with genome-wide approaches.

Given the necessity of both the extraction of DNA and its bisulfite conversion for methylation-based epigenetic tests, there is significant utility in both optimizing and streamlining the sample preparation process. Recently, a simple but powerful technique termed ‘Methylation on Beads’ has been introduced as a means to greatly enhance the sensitivity of methylation-specific analyses of clinical samples [48,49].

Highlighting the challenges

While methylated tumor-specific circulating DNA has shown great promise as a biomarker for numerous forms of cancer, its use as a clinical diagnostic tool can be problematic due to its relative scarcity within biological samples and the fragmented nature of cell-free DNA [50–52]. Even though circulating DNA is found throughout the bloodstream, only a small fraction is likely to come from diseased or cancerous tissue. In the case of methylated DNA, the situation is even more challenging as particular epialleles represent an even smaller subset of this tumor-derived DNA. Due to this extreme rarity, conventional processing techniques have often proven inadequate for reliable extraction and detection from blood samples [53]. Thus, there is a clear need for improved techniques that allow for more efficacious extraction of circulating tumor DNA.

MOB: what & why?

MOB is an amalgamation of multiple recent advancements in DNA isolation and methylation detection. DNA is traditionally extracted from blood or other biological samples through the use of techniques based upon phenol chloroform (PC) and ethanol precipitation or, more recently, using solid phase extraction via silica-based matrices and spin-columns [54,55]. In order to analyze the methylation status of these samples, they must also undergo a separate procedure to perform bisulfite conversion prior to a methylation-sensitive assay such as MSP. This process typically requires numerous labor-intensive steps and transfers between reaction vessels. As a result of this extended sample handling, conventional procedures are often plagued by high sample loss, long assay times, increased contamination, high rates of operator error with variable data and success rates. Furthermore, both residual processing reactants as well as constituents within the biological samples themselves can result in significant inhibition of PCR.

By incorporating both the DNA extraction and bisulfite conversion into a single-tube process, MOB represents an incremental technical advancement in the processing of genomic DNA from biological samples, yet provides significant improvement over traditional and commercial extraction techniques. While originally designed for common sample volumes of 200 μl or less, it has recently been reported that advancements in the MOB process have extended its working range to volumes of up to 2 ml. Additional key improvements in DNA recovery have increased analytical sensitivity 25-fold as compared with standard techniques such as PC and silica-matrix-based extraction techniques [48,49].

At the center of MOB is the use of silica superparamagnetic beads (SSBs) that act as versatile DNA carriers throughout the entire process. SSBs are composed of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles embedded within silica microparticles [44,56–58]. The magnetic nanoparticles endow the particles with action-at-a-distance magnetic properties, allowing for easy handling within reaction vessels, while their superpara-magnetic nature allows the particles to become demagnetized in the absence of a magnetic field, thereby allowing them to be readily dispersed in solution. SSBs have long been utilized as a means of solid phase extraction of nucleic acids by capitalizing on silica’s inherent affinity toward nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropes and/or an appropriately acidic pH. At higher pH (or non-polar solvents), silica notably loses its affinity toward nucleic acids, allowing them to be readily eluted back into solution. Lastly, silica is utilized throughout biochemistry due to its inertness and well-known chemiresistance to most solvents, allowing its use with the vast majority of chemicals.

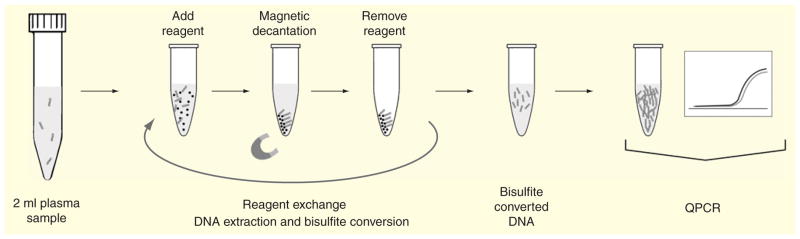

The entire MOB process can be performed using commercially available reagents including the SSBs and a simple magnet or magnetic separator. The basic MOB process is illustrated in Figure 1 [49]. The overall process involves iterations of reagent addition, incubation and magnetic decantation, all within a single reaction vessel. Briefly, a biological sample, such as serum, plasma or sputum, is proteolytically digested in the reaction vessel (typically a 2–15 ml tube) prior to the addition of SSBs. Internal comparisons among several different protease solutions have shown that proteinase K performs superiorly for this purpose. Following proteolytic digestion, SSBs are added to the sample, along with a low pH buffer containing chaotropes, which helps precipitate nucleic acids and greatly facilitates the non-specific adsorption of the nucleic acids within the sample onto the SSBs. Recent advancements in the MOB technique have included the further addition of carrier RNA into each of the binding steps. This carrier RNA is added last to help precipitate and aggregate remaining nucleic acids so as to enhance overall DNA recovery during binding steps [59]. After magnetic decantation, the DNA-laden beads are washed several times before the addition of a high salt, alcohol-based elution buffer to release the purified DNA into solution. Without transfer into a separate vessel, commercially available bisulfite conversion reagents can then be added to the resultant solution and incubated to allow bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosine residues from the recovered DNA into uracil residues. As previously mentioned, this process leaves methylated cytosine residues intact, thereby allowing the methylation status of the DNA to be analyzed downstream [60]. Lastly, following bisulfite conversion, the converted DNA is once again washed through a series of wash buffer additions, each followed by magnetic decantation before the DNA is finally eluted into purified water for analysis.

Figure 1.

Overall, the MOB process requires minimal training and can be performed in as little as 4 h when using the Lightning bisulfite conversion kits (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) [47] compared with the greater than 24 h required for traditional extraction and processing using PC-based methods [61]. The process has additionally been shown to be readily amenable to sample volumes of up to at least 2 ml, allowing for facile concentration of the extracted DNA into final volumes of 100 μl or less. Parallelization is easily accomplished through the use of so-called magnetic separation racks, allowing up to 24 samples to be simultaneously extracted, purified and converted within only a few hours.

In terms of performance, MOB yields surprising improvements in analytical sensitivity. For example, we previously demonstrated that compared with traditional 500 μl PC-based extraction and processing techniques, Ct values decreased by an average of 6.8 cycles when using MOB with 2 ml samples, resulting in 26.8 = 111-fold increased analytical sensitivity (>25-fold taking into the increased starting material) [49]. This dramatic increase can only partially be accounted for by increased DNA recovery and thus we have hypothesized that the bulk of the increase in analytical sensitivity is a result of a significant decrease in PCR inhibition due to increased washing efficiencies [62].

While MOB has been shown to be beneficial in basic research applications, it has the potential to be instrumental to processing all types of samples for clinical cancer detection and treatment. For example, patients have long resisted colon cancer detection via colonoscopy. Colonoscopy is an invasive procedure with a notorious preparation [18,63–65]. It requires a scheduled appointment and cannot be done in the office. Furthermore, current screening recommendations suggest that colonoscopy should be performed every 10 years even if the prior exam was negative. The alternative test, the fecal occult blood test, has a notoriously poor sensitivity and specificity when used in isolation [66,67]. As a result, there is yet to be a reliable non-invasive screening method for the early detection of colon cancer. However, DNA is continually shed into the feces by malignant and pre-malignant cells. This provides an ideal opportunity to use stool as a medium for MOB.

We have previously identified genome-wide methylation changes in colorectal cancer. Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor 2 (TFPI2) was identified as a gene being methylated at its promoter-associated CpG island in almost all invasive colorectal cancers associated with gene silencing. Methylation of the gene TFPI2 was also seen in precursor lesions including adenomas with methylation-associated silencing in 94% of serrated adenomas, 100% of tubular adenomas, 100% of villous adenomas and 99% of invasive colorectal cancers [31]. When tested in stool samples, methylation of this gene had a sensitivity of 89% based on traditional PC extraction methodologies. Colonoscopy, on the other hand, provides a sensitivity of greater than 98% but is an invasive and costly procedure [68]. Isolation of human DNA from stool is currently cumbersome and labor intensive. Alternatively, MOB can be readily amended to extract human DNA from stool in a facile manner, enabling testing for methylation markers such as TFPI2 for early detection of colon cancer. A DNA-based strategy utilizing MOB for stool samples could be used on a yearly basis for a screening mechanism in between colonoscopies. Cologuard was recently approved by the US FDA as an adjunctive screening tool. This test includes methylation detection of two genes, though it does not utilize MOB. Future study would be needed to determine if MOB provided improved sensitivity to current Cologuard screening [25].

Currently, the most immediate applications for MOB remain in the blood-based biomarkers. Upon lysis, cancer cells release DNA into the gastrointestinal tract, but it has also been reported that DNA is shed directly into the peripheral circulation [69,70]. The first documented use of MOB in the detection of cancer in the blood was published in 2013 by Yi et al. in a study documenting the use of two blood-based biomarkers to detect pancreatic cancers with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 85% [32]. This is a particularly important development in pancreatic cancer because most cancers are discovered at late stages, resulting in exceptionally high mortality rates [71]. When compared with the current blood-based biomarker, CA19-9, the use of methylation-based biomarkers was able to detect pre-invasive and early stage disease in a greater number of patients [72].

Pancreatic cancer, while rare, is often deadly [73]. The difficulty is that population-wide screening would result in an unacceptably high number of false positives (current tests have poor positive predictive values) [74]. For this reason, screening must necessarily be limited to patients at high risk for developing pancreatic cancer such as those patients with an extensive family history of the disease. Another subset of patients who may benefit from blood-based tests, as facilitated by the use of MOB, include those patients who have a pancreatic mass found on CT scan or endoscopy. For example, there is occasional uncertainty when distinguishing chronic pancreatitis from cancer on imaging [75,76]. MOB-based tests, in combination with testing for common pancreatic gene mutations including KRAS, PALB2 and GNAS, may allow us to provide better characterization of such lesions [77–79]. Finally, given its amenability to a broad range of sample types, a MOB-based strategy could also be used for surveillance for disease recurrence after resection of pancreatic cancer.

MOB-based sample preparation may also be used for predictive biomarker assays in testing responses to epigenetic therapy. Epigenetic therapy is the use of any pharmacologic agent to reverse the abnormal epigenetic changes that occur in cancer. These treatments include agents that reverse DNA methylation [80]. These demethylating agents are currently approved in the USA for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia [81,82]. Epigenetic therapy has recently been used with some success in lung and ovarian cancers, while clinical trials in colon and breast cancers are ongoing [83–85]. In both the lung and ovarian cancer trials, methylation of tumors was able to be used to predict which patients would respond to epigenetic therapies. Though this requires validation, the mechanism of predictive biomarkers is quite robust as the biomarkers and the therapies both involve methylation of genes.

Expert commentary

Personalized medicine is the future of cancer detection and treatment, however, it is dependent upon robust and validated biomarkers. DNA methylation is a particularly attractive biomarker because it is often cancer-specific and it generally occurs not only in cancers, but also in pre-malignant lesions. This provides a unique opportunity to detect and treat cancers while they are still in early stages. However, its usefulness in the clinical setting has been limited up to this point. This is because detection of DNA methylation required a large amount of DNA material such as a sample collected from a biopsy. A biopsy is considered to be an invasive technique and clinicians limit the use of biopsies to situations where there is a high index of suspicion for cancer.

MOB demonstrates key improvements in DNA recovery, which has significantly increased the sensitivity to detect DNA methylation. This permits DNA methylation detection in samples with low volumes of DNA such as blood, stool and sputum. These samples can be obtained via non-invasive means. As a result, these tests become more attractive to both physicians and patients for use as a screening tool. Testing for these alterations in large populations may help identify cancers at earlier stages, target therapies and improve patient outcomes.

Five-year view

The promise of methylation for the detection and treatment of various cancers has been well established in the literature. However, up to this point, nearly every study has been conducted directly on cancer tissue samples. MOB opens up the possibility of studying cancers indirectly, by examining the bodily samples into which cancer DNA is shed. The major benefit of this is that these samples can be obtained either at home by the patient or in a laboratory by a phlebotomist. There are three major tasks that must be accomplished in the coming years: to develop a panel of genes unique to each tumor type, to establish the fidelity of MOB and to automate the MOB process.

Five years from now, we believe that MOB will be used in a clinical setting to screen patients for cancer. Because it will be relatively new, we do believe that it will be used selectively, such as in those patients with a family or personal history of cancer. We anticipate that it will be used in combination with current detection models such as the use of colonoscopy for colon cancer or mammography for the detection of breast cancer. As more data accumulate regarding the use of MOB, we believe that its place in the clinical setting will expand.

Key issues.

Biomarkers are needed to detect tumors, determine choice of treatment and predict response.

Methylation of CpG islands at the gene promoter region is a cancer-specific phenomenon with excellent promise for biomarkers.

Methylation of several genes in pancreatic and colon cancer has been shown to have excellent specificity and sensitivity for the detection of early stage cancer.

Older methods of methylation detection were cumbersome, operator-dependent and required large amounts of DNA.

Methylation on beads is a technique that permits a more uniform, streamlined and efficient detection of DNA methylation.

Methylation on beads is able to extract and process minute amounts of methylated DNA in the peripheral blood for downstream analysis. This may aid in the early detection of colon and pancreatic cancers in a clinical setting.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Guzzetta AA is supported by an NIH T32 Institutional Training Grant. Ahuja N is supported by the NIH grant NCI K23CA127141, the American College of Surgeons/Society of University Surgeons, Career Development Award and the Lustgarten Foundation. Wang TH is supported by the NIH grants R01CA155305 and U54CA151838. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

• of considerable interest

- 1.Heppner GH. Tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 1984;44(6):2259–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314(5797):268–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O’Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2198–204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin L, Andersen JN, Futreal PA. Cancer genomics: from discovery science to personalized medicine. Nat Med. 2011;17(3):297–303. doi: 10.1038/nm.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Ashfaq R, et al. Multiple biomarkers improve prediction of bladder cancer recurrence and mortality in patients undergoing cystectomy. Cancer. 2008;112(2):315–25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23162. An excellent review of the types of biomarkers, their use in the clinical setting and why DNA methylation is such a promising biomarker. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):301–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laird PW. Early detection: the power and the promise of DNA methylation markers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(4):253–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harlan LC, Hankey BF. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end-results program database as a resource for conducting descriptive epidemiologic and clinical studies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2232–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.94.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, Basler JW. Detection of organ-confined prostate cancer is increased through prostate-specific antigen-based screening. JAMA. 1993;270(8):948–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyers CL. The cancer biomarker problem. Nature. 2008;452(7187):548–52. doi: 10.1038/nature06913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):845–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. NEngl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher B, Anderson S, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy for axillary node-negative, estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-23. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):931–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poste G. Bring on the biomarkers. Nature. 2011;469(7329):156–7. doi: 10.1038/469156a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu S, Loo JA, Wong DT. Human body fluid proteome analysis. Proteomics. 2006;6(23):6326–53. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanash SM, Pitteri SJ, Faca VM. Mining the plasma proteome for cancer biomarkers. Nature. 2008;452(7187):571–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1893–907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2093–103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traverso G, Shuber A, Levin B, et al. Detection of APC mutations in fecal DNA from patients with colorectal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(5):311–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlquist DA, Skoletsky JE, Boynton KA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening by detection of altered human DNA in stool: feasibility of a multitarget assay panel. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(5):1219–27. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmisano WA, Divine KK, Saccomanno G, et al. Predicting lung cancer by detecting aberrant promoter methylation in sputum. Cancer Res. 2000;60(21):5954–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibbe AG, Miller MC, Terstappen LW. Statistical considerations for enumeration of circulating tumor cells. Cytometry A. 2007;71(3):154–62. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sleijfer S, Gratama JW, Sieuwerts AM, et al. Circulating tumour cell detection on its way to routine diagnostic implementation? Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(18):2645–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196(2):261–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. A study detecting early stage colorectal cancer using methylation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 as a biomarker. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Straussman R, Nejman D, Roberts D, et al. Developmental programming of CpG island methylation profiles in the human genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(5):564–71. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1594. The first study using methylation on beads to detect pancreatic cancer in a blood-based assay. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuebel KE, Chen W, Cope L, et al. Comparing the DNA hypermethylome with gene mutations in human colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(9):1709–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glockner SC, Dhir M, Yi JM, et al. Methylation of TFPI2 in stool DNA: a potential novel biomarker for the detection of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4691–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi JM, Guzzetta AA, Bailey VJ, et al. Novel methylation biomarker panel for the early detection of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(23):6544–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(8):3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes LA, Melotte V, de Schrijver J, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype: what’s in a name? Cancer Res. 2013;73(19):5858–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(6):415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swarup V, Rajeswari MR. Circulating (cell-free) nucleic acids – a promising, non-invasive tool for early detection of several human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(5):795–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viet CT, Schmidt BL. Methylation array analysis of preoperative and postoperative saliva DNA in oral cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(12):3603–11. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Fraipont F, Moro-Sibilot D, Michelland S, et al. Promoter methylation of genes in bronchial lavages: a marker for early diagnosis of primary and relapsing non-small cell lung cancer? Lung Cancer. 2005;50(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinert T, Modin C, Castano FM, et al. Comprehensive genome methylation analysis in bladder cancer: identification and validation of novel methylated genes and application of these as urinary tumor markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(17):5582–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cairns P. Detection of promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in urine from kidney cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1022:40–3. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cairns P, Esteller M, Herman JG, et al. Molecular detection of prostate cancer in urine by GSTP1 hypermethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(9):2727–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bird AP. Use of restriction enzymes to study eukaryotic DNA methylation: II. The symmetry of methylated sites supports semi-conservative copying of the methylation pattern. J Mol Biol. 1978;118(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, et al. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(8):E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, et al. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(18):9821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grunau C, Clark SJ, Rosenthal A. Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(13):E65–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahuja N, Li Q, Mohan AL, et al. Aging and DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa and cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58(23):5489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khanna A, Czyz A, Syed F. EpiGnome [trade] Methyl-Seq Kit: a novel post-bisulfite conversion library prep method for methylation analysis. Nat Meth. 2013;10:10. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey VJ, Zhang Y, Keeley BP, et al. Single-tube analysis of DNA. methylation with silica superparamagnetic beads. Clin Chem. 2010;56(6):1022–5. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.140244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keeley B, Stark A, Pisanic TR, Ii, et al. Extraction and processing of circulating DNA from large sample volumes using methylation on beads for the detection of rare epigenetic events. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;425(0):169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50••.Diehl F, Li M, Dressman D, et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(45):16368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507904102. The original study describing the methodology of methylation on beads. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51••.Jung K, Fleischhacker M, Rabien A. Cell-free DNA in the blood as a solid tumor biomarker-A critical appraisal of the literature. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(21–22):1611–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.032. Describes using methylation on beads to detect methylation of circulating tumor DNA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DSB, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(6):426–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeerleder S. The struggle to detect circulating DNA. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):142. doi: 10.1186/cc4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirby KS. New method for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acids - evidence on the nature of bonds between deoxyribonucleic acid and protein. Biochem J. 1957;66(3):495–504. doi: 10.1042/bj0660495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirby KS, Cook EA. Isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from mammalian tissues. Biochem J. 1967;104(1):254–7. doi: 10.1042/bj1040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daimon K, Komai S, Takarada Y. Method of extracting nucleic acids using particulate carrier. Toyo Boseki Kabushiki Kaisha; Japan: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otto P. MagneSil™ paramagnetic particles: magnetics for DNA purification. J Assoc Lab Autom. 2002;7(3):34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan WH, Wang KM, He XX, et al. Bionanotechnology based on silica nanoparticles. Med Res Rev. 2004;24(5):621–38. doi: 10.1002/med.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallagher ML, Burke WF, Orzech K. Carrier RNA enhancement of recovery of DNA from dilute-solutions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;144(1):271–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang RYH, Gehrke CW, Ehrlich M. Comparison of bisulfite modification of 5-methyldeoxycytidine and deoxycytidine residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(20):4777–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.20.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myöhänen S, et al. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(18):9821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schrader C, Schielke A, Ellerbroek L, Johne R. PCR inhibitors - occurrence, properties and removal. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113(5):1014–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dominitz JA, Eisen GM, Baron TH, et al. Complications of colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(4):441–5. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, et al. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53(2):277–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lofton-Day C, Model F, Devos T, et al. DNA methylation biomarkers for blood-based colorectal cancer screening. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):414–23. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.095992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2704–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahlquist DA, Wieand HS, Moertel CG, et al. Accuracy of fecal occult blood screening for colorectal neoplasia. A prospective study using Hemoccult and HemoQuant tests. JAMA. 1993;269(10):1262–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rockey DC, Paulson E, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Analysis of air contrast barium enema, computed tomographic colonography, and colonoscopy: prospective comparison. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):305–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17784-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DS, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(6):426–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fleischhacker M, Schmidt B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer – a survey. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775(1):181–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gemmel C, Eickhoff A, Helmstadter L, Riemann JF. Pancreatic cancer screening: state of the art. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3(1):89–96. doi: 10.1586/17474124.3.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fry LC, Monkemuller K, Malfertheiner P. Molecular markers of pancreatic cancer: development and clinical relevance. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393(6):883–90. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klapman J, Malafa MP. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: why, who, and how to screen. Cancer Contr. 2008;15(4):280–7. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Erkan M, Hausmann S, Michalski CW, et al. The role of stroma in pancreatic cancer: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(8):454–67. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Erkan M, Hausmann S, Michalski CW, et al. How fibrosis influences imaging and surgical decisions in pancreatic cancer. Front Physiol. 2012;3:389. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(92):92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brune K, Hong SM, Li A, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of familial pancreatic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(12):3536–42. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324(5924):217. doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):2042–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81•.Kaminskas E, Farrell AT, Wang YC, et al. FDA drug approval summary: azacitidine (5-azacytidine, Vidaza) for injectable suspension. Oncologist. 2005;10(3):176–82. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-3-176. Uses DNA methylation to predict patients’ response to epigenetic therapies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wijermans P, Lubbert M, Verhoef G, et al. Low-dose 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, a DNA hypomethylating agent, for the treatment of high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: a multicenter phase II study in elderly patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(5):956–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Juergens RA, Wrangle J, Vendetti FP, et al. Combination epigenetic therapy has efficacy in patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(7):598–607. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fu S, Hu W, Iyer R, et al. Phase 1b-2a study to reverse platinum resistance through use of a hypomethylating agent, azacitidine, in patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(8):1661–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matei D, Fang F, Shen C, et al. Epigenetic resensitization to platinum in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2197–205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]