Abstract

Objective

Teachable moments (TM) are opportunities created through physician–patient interaction and used to encourage patients to change unhealthy behaviors. We examine the effectiveness of TMs to increase patients’ recall of advice, motivation to modify behavior, and behavior change.

Methods

A mixed-method observational study of 811 patient visits to 28 primary care clinicians used audio-recordings of visits to identify TMs and other types of advice in health behavior change talk. Patient surveys assessed smoking, exercise, fruit/vegetable consumption, height, weight, and readiness for change prior to the observed visit and 6-weeks post-visit.

Results

Compared to other identified categories of advice (i.e. missed opportunities or teachable moment attempts), recall was greatest after TMs occurred (83% vs. 49–74%). TMs had the greatest proportion of patients change in importance and confidence and increase readiness to change; however differences were small. TMs had greater positive behavior change scores than other categories of advice; however, this pattern was statistically non-significant and was not observed for BMI change.

Conclusion

TMs have a greater positive influence on several intermediate markers of patient behavior change compared to other categories of advice.

Practice implications

TMs show promise as an approach for clinicians to discuss behavior change with patients efficiently and effectively.

Keywords: Health promotion, Health behavior change, Communication, Primary care, Teachable moment

1. Introduction

Unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, lack of physical activity and poor nutrition are responsible for a significant portion of morbidity and mortality [1–4]. The prevalence of excess weight, smoking and sedentary lifestyle in developed countries is substantial. In the United States, 84.5% of adults visiting a primary care clinician are overweight, smoke cigarettes, or fail to exercise at the recommended levels [5]. The label “teachable moment” (TM) has been applied to health behavior change messages that leverage the salient features of a patient’s particular circumstance to create powerful or persuasive advice [6–8] for patients in the primary care setting [9–11]. Initially conceived as serendipitous events caused by a constellation of emergent factors [12–14], recent work has examined TMs as opportunities created through the patient– clinician interaction and utilized by patients and physicians to encourage health behavior change [15–17].

Our prior work has identified three essential communication components of a TM: (1) talk that links a patient’s salient concern to the health risk, (2) talk designed to motivate the patient to change and (3) a patient response that indicates engagement and a commitment toward changing the identified behavior [17]. The current study builds on this work and examines the effectiveness of a ‘teachable moment’ for increasing patient recall of advice, perceived helpfulness of the advice, motivation to modify behavior, and positive behavior change.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and participants

This cross-sectional cohort study included primary care clinicians and a sample of their adult patients. All primary care physicians in a regional, practice-based research network who care for adult patients were invited to participate in the study. Of 94 invited family and internal medicine clinicians, 41 (44%) agreed to participate. Thirteen clinicians who agreed to participate were excluded from data collection because of insufficient patient volume (n = 9) or because the practice was too far from the research center (n = 4).

Consecutive patient care days were scheduled for data collection with each participating clinician from March 2006 through December 2008. Adult patients (18–70) scheduled for a visit with a participating clinician were eligible to participate. An invitation to participate was mailed to patients, and verbal consent was obtained by phone. On the day of their office visit, a study team member met the patient and confirmed consent. Clinician and patient participants were informed that the study was about clinician–patient communication; specific study hypotheses were not shared. The University Hospitals Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures.

2.2. Data collection

Consenting patients completed three surveys by phone. Approximately 1–3 days prior to the scheduled visit, demo-graphics, current health behaviors and readiness to change health behaviors were assessed. Within 48 h of the observed visit, patient recall of health behavior discussions, satisfaction and readiness to change were assessed. Six weeks after the observed visit, information collected at baseline was reassessed. Each visit was audio-recorded.

2.3. Data management

Audio recordings were transcribed and text data were organized using Atlas.ti v5 (Scientific Software, GmbH). Coded data from the transcripts were exported and linked with the patient survey data using a unique study identifier and tabulated using SPSS v19.

2.4. Main measures

Height, weight and current health behaviors, including ciga-rette smoking, physical activity, and daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, were assessed by survey (see Appendix) as were patients self-reported diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and high cholesterol status. Patients who reported current cigarette smoking were identified as at risk for smoking. Patients engaging in less than 30 min of moderate exercise 5 days per week were identified as at risk for physical inactivity. Obesity risk was defined as having (1) a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or greater and the presence of one of the four chronic conditions listed above, or (2) a BMI greater than 30. Under-consumption of fruits and vegetables was defined as fewer than 4 cups of fresh fruit, fruit or vegetable juice, or vegetables per day.

2.4.1. Categorizing talk as teachable moments and other types of health behavior advice

Talk about smoking cessation, weight management, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, or increasing physical activity was considered a TM if it included: (1) talk that linked a patient’s salient concern to the health risk, (2) talk designed to motivate the patient to change, and (3) a patient response that indicated a commitment toward changing the identified behavior. A salient patient concern was defined as a symptom, worry or life issue discussed during the visit that was both meaningful to the patient and could be linked to the unhealthy risk factor (e.g. smoking, lack of exercise). Talk designed to motivate the patient to change was defined by a clinician’s attempt to persuade, motivate, or support a decision to change the health behavior. A patient response indicating commitment toward changing the identified behavior was defined as a patient display of willingness and engagement to undertake the behavior change [17].

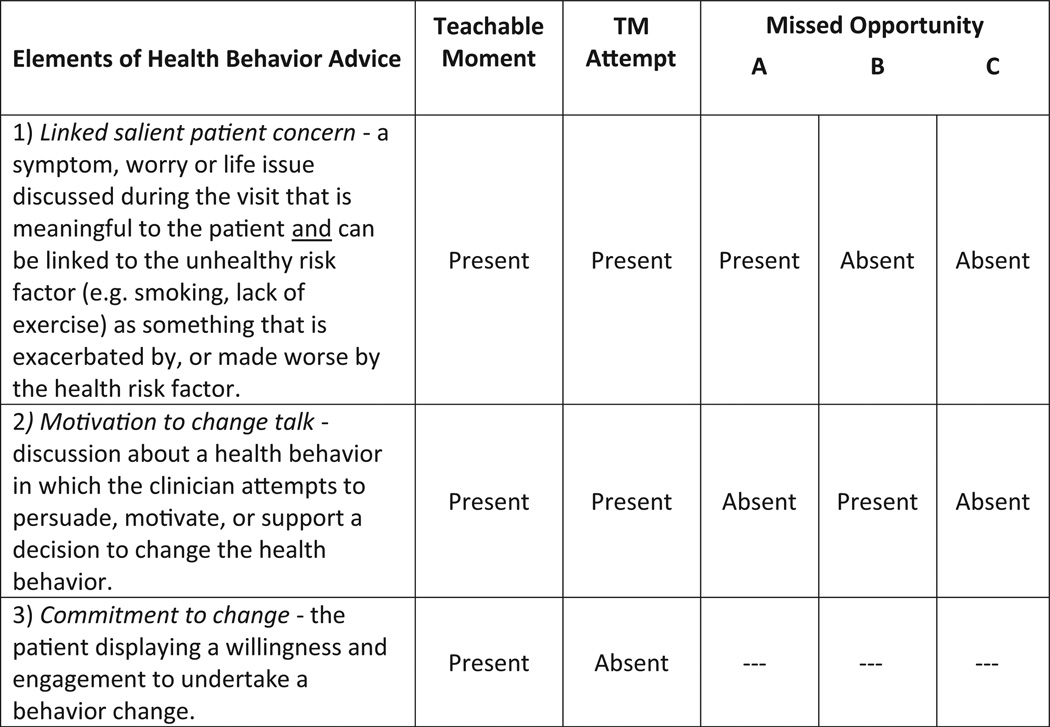

Variations of advice that lacked key elements of a teachable moment were categorized as a “teachable moment attempt” or “missed opportunity” (see Fig. 1). Teachable moment attempts lacked a patient response that indicated commitment toward changing. Missed opportunities were categorized into three groups, advice that: (A) linked a patient’s salient concern to a health behavior but did not include motivation to change talk, (B) included talk to motivate the patient to change but had no link to a salient concern, or (C) talk about a health behavior that was missing both a link to a salient concern and change motivating talk.

Fig. 1.

Key elements of the teachable moment and variations of health behavior advice.

Because patients could be at risk for more than one health behavior, 1408 opportunities for TMs were evaluated among 698 patient visits. The label “no discussion” was used when patients at risk for a health behavior had no discussion of that health behavior. Health behavior discussions in which the patient reported actively working to improve a health behavior and the clinician confirmed the patient’s improvement as adequate, were excluded from the analyses as non-opportunities.

2.4.2. Intermediate outcome measures

Recall and usefulness of health behavior discussions were assessed by survey within 48 h of the visit. Patients rated importance and confidence of changing health behaviors on a scale of 1–10 before and after the visit. The patient’s readiness to change using 6 levels of readiness (18) was also assessed before and after the visit. For the analyses, change scores for readiness to change were categorized into an increase in readiness versus no change or a decrease in readiness.

Potential adverse outcomes measured were patient satisfaction and visit duration. Patients were asked “How would you rate your satisfaction with today’s visit?” using a 5-point scale from poor to excellent [18]. Visit duration was computed as the total face-to-face time with the clinician evaluated from the audio-recording.

2.5. Analysis

Chi-square statistics and ANOVA were used to test the association of health behavior advice types with patient char-acteristics, potential adverse outcomes, and intermediate out-comes. Analyses evaluating difference in importance to change, confidence to change, and increased readiness to change after the visit were adjusted for baseline values. Patient-reported health behaviors before the visit and 6 weeks after the visit were used to compute a change score for each health behavior. Health behavior change scores were standardized (z scores) and an improvement in the health behavior received a positive score. Using z scores permitted examination of the association of type of health behavior advice with any health behavior change, as well as comparison across health behaviors. The p values for all outcome associations were adjusted for the effect of discussions clustered within clinicians using generalized linear mixed models. All associations were evaluated at p < 0.05. Post hoc tests of differences between groups are reported. At the inception of the project, power and sample sizes were estimated using meaningful effect sizes of 0.30 of a standard deviation for continuous variables and 20% for categorical variables; because of small sample sizes across type of health behavior advice and thus, modest power to detect statistical significance for some comparisons, interpretations of associations were also guided by the observed effect sizes.

3. Results

The 28 clinician participants representing 16 community-based practices were residency-trained: 71% in internal medicine and 29% in family medicine. The mean number of years since completing residency training was 14.1 ± 8.0. Half of the clinicians were female and 17 (61%) were white, 8 (29%) black, 2 (7%) Asian, and 1 (4%) was another race. On average, clinicians had 30 patients enrolled in the study (range 3–47; SD 11.9).

Forty-seven percent of patients eligible for the study and contacted by phone by the study team agreed to participate and completed a pre-visit survey. Of the 1108 patients who completed a pre-visit survey, 877 (79%) presented for their visit and completed written consent. This rate was largely due to high no show rates at some practices. An audible audio-recording was obtained for 93% of these patients. Compared to patients who completed only the pre-visit survey, patients who completed the audio-recorded portion of data collection (n = 811) were more likely to be white (p < 0.001) and to report education beyond high school (p < 0.01), but were otherwise similar.

The characteristics of the 811 patients who completed a pre-visit survey and had an audible recording of their visit included in this analysis are reported in Table 1. Of these patients, 698 (86%) had at least one opportunity for discussion about a health behavior of interest due to risk status; 364 (45%) of these “at risk” patients had a health behavior discussion during the observed visit. Demographic characteristics and visit type of patients whose visit included a health behavior discussion were similar to those that did not have a discussion (see Table 1). However, patients who had a health behavior discussion were significantly more likely to have a chronic condition (p < 0.001) and a longer visit (p < 0.001). On average, patients with a discussion were at risk for 2.4 health behaviors and had 1.15 health behavior discussions. The total number of health behavior discussions for the sample was n = 418.

Table 1.

Patient and visit characteristics for all study participants, participants at risk for at least one health behavior, and participants with at least one health behavior (HB) discussion.

| Patient characteristic | All participants, n = 811 | At risk participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total at risk, n = 698 | No HB discussion, n = 334 | Any HB discussion, n = 364 | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 52 ± 12 | 53 ± 11 | 53 ± 12 | 52 ± 10 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 480 (60) | 400 (58) | 192 (58) | 208 (57) |

| Black | 289 (36) | 265 (38) | 127 (38) | 138 (38) |

| Other | 37 (5) | 30 (4) | 13 (4) | 17 (5) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 16 (2) | 14 (2) | 8 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Male, n (%) | 264 (33) | 227 (33) | 104 (31) | 123 (34) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| High school diploma or less | 237 (29) | 220 (32) | 102 (31) | 118 (32) |

| Some college | 254 (31) | 213 (31) | 101 (30) | 112 (31) |

| College degree or more | 320 (40) | 265 (38) | 131 (39) | 134 (37) |

| Chronic conditionsa, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 160 (20) | 145 (21) | 58 (17) | 87 (24) |

| High blood pressure | 327 (40) | 303 (43) | 134 (40) | 169 (46) |

| High cholesterol | 394 (49) | 365 (52) | 162 (49) | 203 (56) |

| Heart disease | 66 (8) | 62 (9) | 28 (8) | 34 (9) |

| None of the above conditionsb | 255 (31) | 189 (27) | 111 (33) | 78 (21) |

| Self-reported health status, n (%) | ||||

| Excellent | 105 (13) | 81 (12) | 49 (15) | 32 (9) |

| Very good | 250 (31) | 205 (29) | 89 (27) | 116 (32) |

| Good | 249 (31) | 225 (32) | 107 (32) | 118 (32) |

| Fair | 167 (21) | 151 (22) | 72 (22) | 79 (22) |

| Poor | 40 (5) | 36 (5) | 17 (5) | 19 (5) |

| Visit characteristic | ||||

| Visit type, n (%) | ||||

| Acute care | 217 (27) | 187 (27) | 101 (31) | 86 (24) |

| Chronic care | 417 (52) | 372 (54) | 173 (53) | 199 (55) |

| Well care | 168 (21) | 132 (19) | 55 (17) | 77 (21) |

| Visit durationb, mean ± SD | 20 ± 11 | 19 ± 11 | 18 ± 10 | 21 ± 12 |

Multiple responses allowed, percentages add to more than 100%.

Significant association with HB discussion among those at risk (p < 0.05).

The unit of analysis for subsequent analyses is the opportunity for a health behavior discussion. TMs were observed in only 58 (14%) discussions (Table 2). Teachable moment attempts and missed opportunities represented 25% and 61% of observed discussions, respectively. The approaches used to communicate health behavior change advice (i.e. TM, teachable moment attempt or a missed opportunity) did not vary by patient demographic or health status groups.

Table 2.

The association of health behavior advice type (n = 418 discussions among ‘at risk’ patients) with patient and visit characteristics.

| Patient characteristic |

Teachable moment, n = 58 |

TM attempt, n = 106 |

Missed opportunityb |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||||

| n = 44 | n = 73 | n = 137 | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 51 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 | 55 ± 10 | 50 ± 11 | 53 ± 10 | 0.05 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| White | 47 | 59 | 52 | 56 | 56 | 0.90 |

| Black | 47 | 37 | 43 | 38 | 37 | |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Hispanic, % | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.66 |

| Male, % | 43 | 33 | 32 | 30 | 34 | 0.60 |

| Educationa, % | ||||||

| High school diploma or less | 29 | 42 | 36 | 29 | 32 | 0.87 |

| Some college | 33 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 37 | |

| College degree or more | 38 | 34 | 36 | 43 | 31 | |

| Any chronic condition, % | 76 | 86 | 80 | 70 | 82 | 0.11 |

| Self-reported health statusa, % | ||||||

| Excellent | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 0.74 |

| Very good | 41 | 36 | 16 | 41 | 25 | |

| Good | 22 | 31 | 55 | 27 | 37 | |

| Fair | 22 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | |

| Poor | 7 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | |

| Visit type, % | ||||||

| Acute care | 28 | 17 | 16 | 25 | 27 | 0.07 |

| Chronic care | 57 | 61 | 70 | 43 | 53 | |

| Well care | 16 | 22 | 14 | 32 | 20 | |

Linear-by-linear association p-value used to compare ordinal variables.

Missed opportunities: (A) link to health concern present but change talk absent; (B) change talk present but link to health concern absent; (C) link to health concern and change talk absent.

Table 3 shows the association between categories of health behavior discussions and intermediate outcomes. For all of the analyses in Table 3, TMs are compared with teachable moment attempts, missed opportunities and no health behavior discussion and post hoc comparisons are reported in footnotes. Recall of health behavior discussion was greatest when clinicians communicated using a TM (83%) compared to other approaches for delivering advice (49–74%). TMs had the highest proportion of cases reporting the discussion was useful (96%) versus all other categories (78–84%), though differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.31). Overall, TMs had the greatest proportion of cases reporting positive change in importance and confidence from pre-visit to post-visit, as well as increase in readiness to change; however the magnitude of differences among the advice categories was small, and not significant.

Table 3.

The association of health behavior advice with intermediate, health behavior, and potential adverse outcomes for 1408 opportunities for health behavior discussion during patient visits.

| Outcome measures | Teachable moment, n = 58 |

TM attempt, n = 106 |

Missed opportunitye |

No discussion, n = 990 |

pf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||

| n = 44 | n = 73 | n = 137 | |||||

| Exit survey outcomes | |||||||

| Recall health behavior discussion, % | 83 | 74 | 55 | 64 | 49 | – | <0.001g |

| Health behavior discussion useful, % | 96 | 83 | 78 | 83 | 84 | – | 0.31 |

| Importance of changing health behaviora | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 0.04h |

| Confidence in changing health behaviora | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 0.21 |

| Stage of change, % positive movement | 33 | 26 | 30 | 25 | 21 | 16 | 0.001i |

| Health behavior change scoreb,c | |||||||

| All health behaviors | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.21 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.58 |

| Cigarettes smoked (129 at risk, 74 discussions) | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.39 | −0.26 | −0.44 | −0.06 | 0.12 |

| Body mass index (388 at risk, 189 discussions) | −0.19 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.95 |

| Physical activity (290 at risk, 53 discussions) | 0.56 | 0.17 | −0.22 | −0.43 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.55 |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption (371 at risk, 36 discussions) | 0.55 | 0.35 | – | −0.38 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.80 |

| Potential adverse outcomes | |||||||

| Visit durationd, mean ± SD | 22 ±12 | 20 ±11 | 19 ± 11 | 22 ±11 | 22 ±12 | 18 ±10 | 0.01j |

| Patient satisfaction, % | |||||||

| Poor/fair/good | 13 | 26 | 16 | 21 | 13 | 22 | 0.69 |

| Very good | 35 | 30 | 32 | 30 | 33 | 37 | |

| Excellent | 52 | 44 | 52 | 49 | 54 | 51 | |

Note: Recall and usefulness outcomes analyses did not include “NoTalk” group.

Mean score on a scale of 1–10 with 1 being not important/confident at all and 10 being very important/confident.

Standardized Z scores represent negative and positive health behavior change at 6 weeks.

Sample sizes reflect the number of individuals with a complete 6-week survey, the maximum sample size for this analysis is n = 1178 teachable moment opportunities.

When no talk group is excluded there is no difference in visit duration among the 5 health behavior discussion groups (p = 0.685).

Missed opportunities: (A) link to health concern present but change talk absent; (B) change talk present but link to health concern absent; (C) link to health concern and change talk absent.

The ICCs ranged from 0.001 to 0.054. Thus, the overall impact of clustering was small (i.e. 6% or less of the variability in each health behavior outcome measure was explained by the clinician). For potential adverse outcomes, the ICCs were substantially higher, 0.25 for visit duration and 0.10 for satisfaction.

Post hoc 2 × 2 cross tabulations with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons indicated patient recall of advice was significantly greater when a teachable moment or teachable moment attempt was used compared to discussions with no link and no change talk (missed opportunity C) and when a teachable moment was used compared to discussions with a link present but no change talk (missed opportunity A), p <0.005.

Post hoc comparisons using the least significant difference pairwise multiple comparison test (LSD) showed that importance of changing was greater when a teachable moment (p = 0.05) or teachable moment attempt (p = 0.03) was used versus no discussion.

Post hoc comparisons using LSD showed that teachable moments had a greater proportion of cases reporting positive stage of change movement compared to no discussion (p = 0.002) and discussions categorized as a missed opportunity C (p = 0.05); teachable moment attempts (p = 0.02) and discussions categorized as a missed opportunity A (p = 0.03) also had a higher proportion of cases reporting positive movement when compared to no discussion.

Post hoc comparisons using LSD showed that visit duration was longer when a teachable moment (p = 0.03) or missed opportunity B (p = 0.004) or C (p <0.001) were used compared to visits with no health behavior discussion; however, when the no discussion group is excluded no significant differences exist.

Using the omnibus measure of the health behavior change score, TMs were not significantly different from other types of advice in affecting change in health behaviors. Examining the specific health behaviors, the pattern of association shows that TMs and teachable moment attempts generally had greater positive change scores than the other categories of advice. This pattern was not observed for BMI change, which represents the largest group of discussions and the largest proportion of TMs. When weight discussions are excluded from the summary health behavior change score, the mean z-score by discussion category is as follows: TM (0.33), teachable moment attempt (0.21), no motivation to change talk (0.26), no link (−0.32), no link and no motivation to change talk (−0.12), and no talk (−0.01), p-value = 0.105. Considering the magnitude of effect size, the TM appears to perform the best, but not meaningfully different (effect size 0.30 or greater) than a teachable moment attempt or a missed opportunity that included a link but was lacking talk to motivate change. Those discussions that lack a link that is salient to the patient appear to have a negative effect on behavior change (−0.32 and −0.12 respectively) and perform worse than no discussion (−0.01).

Finally, compared to the other types of health behavior discussions (excluding no health behavior talk), visits including a TM were not different in visit length or patient satisfaction.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This research provides tentative evidence that the TM communication approach of linking a problematic health behavior to a salient patient concern, transitioning to health behavior change talk, and constructing this talk to elicit the patient’s commitment to health behavior change has a positive effect on intermediate health behavior change outcomes. The TM approach is feasible in the context of routine primary care, does not adversely affect patient satisfaction with the visit, and is not limited to certain types of visits or specific patient groups.

Conceived as a universal approach for health behavior change discussion, it is significant that TMs occurred in discussions of all health behavior topics examined: smoking cessation, weight management, physical activity and fruit/vegetable consumption. This suggests that the TM approach is applicable to a range of health behaviors and is likely to be useful in general practice. TMs occurred during only 14% of the discussions in this sample. This limits our power to detect statistically significant differences in outcomes, and we relied on examining the magnitude of effect. However, while the pattern of associations between TMs and outcomes for smoking, physical activity and fruits/vegetable consumption were similar, there was no positive association between TMs and BMI change at six weeks. This is a conundrum because BMI change requires a patient to make dietary changes and/or change levels of physical activity, and our study shows a positive association between TMs and both of these antecedent behavior changes. It is possible that change in BMI may be too crude of a measure for assessing the impact on weight manage-ment only six weeks after a discussion takes place. Further work is needed to determine if measures of small health behavior changes are predictors of future BMI change. Additionally, more research is needed to determine the influence of the TM on BMI over a longer follow-up period.

Each discussion classified as a TM in this sample included the three key elements; however, there was variation in how each element was accomplished. Some of that variation may represent tailoring to the context of the visit. Other variation might represent differences in clinicians’ skill in productively moving health behavior change discussions forward through patient engagement. Developing a guide for how to efficiently address each of the key elements may be a useful first step toward skill-building. Further, while TMs represent only 14% of the cases in our study, many of the other types of advice include elements of the approach. With some skill-building, it is likely other types of advice could be shifted to be TMs. For example, while many clinicians commonly transition talk about health behavior change by linking to a problem raised during the visit, intentionally linking to a concern that is salient to the patient is an important distinction that clinicians could learn to make. The substantial number of opportunities without a link to a patient’s salient concern illustrates the significant potential for minor changes in the pattern of the clinician–patient discussion to increase patient’s engagement in the topic.

The TM approach highlights the relevance of linking the health behavior to a patient’s salient concern as a strong, persuasive move in the discussion. However, this strong persuasive move (linking), frequently used by clinicians, can generate resistance. Enhancing techniques to navigate patient resistance to behavior change could complement the TM approach and may result in a shift from what we observe as a teachable moment attempt to a full TM, where the patient and clinician productively move forward in the discussion with a plan for behavior change. Patient-centered health behavior counseling strategies, such as motivational interviewing emphasize engaging the patient to identify, examine, and resolve ambivalence about change [19,20]. Pragmatically adapting aspects of motivational interviewing to the primary care setting, specifically, communication skills for eliciting the patient’s perspective, adapting to resistance, and partnering to encourage behavior change [21–25], could complement the TM approach and improve skills for negotiating patient resistance and ambivalence to change.

This study is strengthened by direct-observation in community-based practices with substantial representation of minority patients. Nearly one-third of the enrolled clinicians practiced at federally qualified health centers. One potential limitation of this study is the possibility that the presence of an audio-recording device may have influenced the frequency of health behavior discussions during visits. However, participating clinicians and patients were blinded to specific study hypotheses, and the majority of participants reported that audio-recording the visit did not alter their behavior. Similarly, the administration of the pre-visit survey, which asked patients about current health behaviors, may have influenced the patients’ behavior during visits; however, this potential effect would have likely been the same across all participants and thus seems unlikely to have a confounding effect on the findings reported here. The short follow-up period to monitor change after a single visit represents an additional potential weakness. Nonetheless, it is possible that if a small change can be made after a single primary care visit, the cumulative effect of multiple encounters can potentially increase the magnitude of behavior change. Examining longitudinal change of primary care patients is an important step for future research.

4.2. Conclusion

This study provides evidence that a TM has a greater positive influence on several intermediate markers of patient behavior change compared to other categories of advice occurring naturally during primary care visits. Future research should focus on: (1) examining the feasibly of training clinicians in the standardized delivery of TMs, (2) examining the effect of TM on health behavior change longitudinally, and (3) incorporating other resource components such as office staff and referrals to complement and extend the TM approach.

4.3. Practice implications

This study shows that TMs are applicable to a range of health behaviors and may represent a more effective approach to behavior change discussion, relative to other types of advice, which does not require additional visit time. Particularly if guided by specific skill-building training, the TM could serve clinicians as a powerful strategy to address patient health behavior change during routine primary care encounters.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the clinician and patient participants of this study, who made the conduct of this study possible. This project was funded by a grant to Susan Flocke, R01 CA 105292 and was also supported by the Behavioral Measurement Core Facility and the Practice Based Research Network Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA43703). The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendix

Cigarette smoking

Assessment items

Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?

Have you smoked at least part of a cigarette in the last 7 days?

Risk evaluation

At risk if responded ‘yes’ to both items.

Sources

Guided by recommendation by Glasgow et al. [28], items based on CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [29] and Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) consensus item [30].

Physical activity

Assessment introductions and items

Physical activities are activities that increase your heart rate, whether you do them for pleasure, work or to get somewhere.

Vigorous activities are when you heart beats rapidly, you breathe hard and sweat. Examples are aerobic classes, jogging, basketball, fast swimming, long distance biking, or racquetball (or wheelchair sports). Think only of the activities that you did for at least 10 min at a time.

How many days per week do you do vigorous physical activities?

On those days, how many minutes do you typically do vigorous physical activities? Moderate activities are when your heart beats faster than normal but the activity is not exhausting. Examples are strength training, biking, or swimming (some wheelchair exercise). Think only of the activities that you did for at least 10 min at a time. Do not include walking.

How many days per week do you do moderate physical activities?

On those days, how many minutes do you typically do moderate physical activities? Now I’m going to ask you about different kinds of walking you might do. Brisk walking could count as moderate activity if it increases your heart rate and makes you breathe faster. This walking must also be maintained for at least 10 min at a time.

How many days per week do you do this type of walking?

How many minutes do you typically spend walking on one of those days?

Risk evaluation

Vigorous activity was weighted × 2.5. At risk if weekly minutes of vigorous activity × 2.5 + moderate activity + brisk walking combined was less than 150 min total (i.e. equivalent to less than 5 days a week for 30 min per day).

Sources

Items adapted from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [31] and CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [29].

Fruit and vegetable consumption

Assessment introduction and items

I’m going to ask some questions about eating fruits and vegetables. Think about your eating habits over the past month when you answer them.

- How frequently did you eat fresh fruit?Times per day and times per week

On average how large were those portions in cups?

- How frequently did you drink 100% fruit or vegetable juice?Times per day and times per week

Each time you drank fruit or vegetable juice, how many cups did you typically drink?

- How frequently did you eat uncooked, leafy greens?Times per day and times per week

On average how large were those portions in cups?

- How frequently did you eat raw or cooked vegetables, not counting leafy greens or potatoes?Times per day and times per week

On average how large were those portions in cups?

Risk evaluation

At risk if total average daily consumption of fresh fruit, fruit or vegetable juice, leafy greens and other vegetables per day was fewer than 4 cups.

Sources

Items were written to evaluate both the frequency and the portion size in cups of fruits and vegetables [32]. Items were largely adapted from NIH Eating at America’s Table Study Quick Food Scan [33] with intake guidelines from the Healthy People 2010 recommendations [34] and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005 [35].

Footnotes

Preliminary versions of these findings were presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group in Banff Canada, November 2011 and the American Society of Preventive Oncology in Washington DC, March 2012.

References

- 1.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm JJ, Murray CJL, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia H, Lubetkin EI. The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2005;27:156–164. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Forecasting the effects of obesity and smoking on U.S. life expectancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2252–2260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health interview survey; 2011, Data Release. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasgow RE, Eakin EG, Fisher EB, Bacak SJ, Brownson RC. Physician advice and support for physical activity: results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Smith M, Hogarth DK. Smoking cessation: the potential role of risk assessment tools as motivational triggers. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:26–33. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.084947. quiz 31–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaèn CR, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC. Making time for tobacco cessation counseling. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: the power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:320–323. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonarow GC. In-hospital initiation of statins: taking advantage of the ‘teachable moment’. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70:502–506. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlos RC, Fendrick AM. Improving cancer screening adherence: using the teachable moment as a delivery setting for educational interventions. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow RE, Stevens VJ, Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, Lichtenstein E. Changes in smoking associated with hospitalization: quit rates, predictive variables, and intervention implications. Am J Heal Promot. 1991;6:24–29. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBride CM, Puleo E, Pollak KI, Clipp EC, Woolford S, Emmons KM. Understanding the role of cancer worry in creating a teachable moment for multiple risk factor reduction. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:790–800. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Lawson PJ, Casucci BA, Flocke SA. Identifying teachable moments for health behavior counseling in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e8–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin HR, Gandek B, Roger WH, Kisinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, et al. Patients’ ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;270:835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emmons K, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings: opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing preparing people to change addictive behavior. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Why do people change? In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spanou C, Simpson SA, Hood K, Edwards A, Cohen D, Rollnick S, et al. Preventing disease through opportunistic, rapid engagement by primary care teams using behaviour change counselling (PRE-EMPT): protocol for a general practice-based cluster randomised trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll JK, Antognoli E, Flocke SA. Evaluation of physical activity counseling in primary care using direct observation of the 5As. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:416–422. doi: 10.1370/afm.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasgow RE, Ory MG, Klesges LM, Cifuentes M, Fernald DH, Green LA. Practical and relevant self-report measures of patient health behaviors for primary care research. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:73–81. doi: 10.1370/afm.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes J, Keely J, Niaura R, Ossip-Klein D, Richmond R, Swan G. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Physicial Activity Questionnaire. IPAQ English questionnaires. 2002:71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim DJ, Holowaty EJ. Brief, validated survey instruments for the measurement of fruit and vegetable intakes in adults: a review. Prev Med (Baltim) 2003;36:440–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Kahle LL, Midthune D, et al. Evaluation of 2 brief instruments and a food-frequency questionnaire to estimate daily number of servings of fruit and vegetables. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1503–1510. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005. 2005 [Google Scholar]