Abstract

Humans are reported to discount delayed rewards at lower rates than nonhumans. However, nonhumans are studied in tasks that restrict reinforcement during delays, whereas humans are typically studied in tasks that do not restrict reinforcement during delays. In nonhuman tasks, the opportunity cost of restricted reinforcement during delays may increase delay discounting rates. The present within-subjects study used online crowdsourcing (Amazon Mechanical Turk, or MTurk) to assess the discounting of hypothetical delayed money (and cigarettes in smokers) under four hypothetical framing conditions differing in the availability of reinforcement during delays. At one extreme, participants were free to leave their computer without returning, and engage in any behavior during reward delays (modeling typical human tasks). At the opposite extreme, participants were required to stay at their computer and engage in little other behavior during reward delays (modeling typical nonhuman tasks). Discounting rates increased as an orderly function of opportunity cost. Results also indicated predominantly hyperbolic discounting, the “magnitude effect,” steeper discounting of cigarettes than money, and positive correlations between discounting rates of these commodities. This is the first study to test the effects of opportunity costs on discounting, and suggests that procedural differences may partially account for observed species differences in discounting.

Keywords: delay discounting, opportunity cost, money, cigarette, hypothetical, crowdsourcing, human

Delay discounting is the tendency for organisms to devalue an outcome because its receipt is delayed. In humans, the extent to which one discounts future outcomes is associated with a variety of problem behaviors. For example, substance-dependent individuals tend to discount delayed rewards to a greater degree than demographically matched control participants (for a meta-analysis of this literature, see MacKillop et al., 2011). Rates of delay discounting are also correlated with treatment response in substance-dependent individuals (e.g., Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007; Sheffer et al., 2012; Stanger et al., 2012; Washio et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2007; but see Heinz, Peters, Boden, & Bonn-Miller, 2013, & Peters, Petry, LaPaglia, Reynolds, & Carroll, 2013). Greater rates of delay discounting are associated with subsequent rapid self-administration acquisition, escalation of drug-taking, and drug-primed reinstatement in nonhumans (e.g., Carroll, Anker, Mach, Newman, & Perry, 2010; Diergaarde et al., 2008; Stein & Madden, 2013), which is suggestive of a causal role for delay discounting in the development of substance abuse. Beyond substance abuse, greater delay discounting is related to a myriad of other important behavioral health issues: gambling, obesity, lack of exercise, skipping breakfast, not using safety belts, not using sunscreen, not having mammograms, not having Pap smears, not having prostate examinations, not having dental visits, not having cholesterol tests, and not having flu shots (Axon, Bradford, & Egan, 2009; Bradford, 2010; Daugherty & Brase, 2010; Dixon, Marley, & Jacobs, 2003; Petry, 2001; Weller, Cook, Avsar, & Cox, 2008). Given these robust associations between discounting and maladaptive behaviors, understanding the effects of behavioral or biological variables on discounting may inform programs, interventions, and policy making that improves public health.

Humans have appeared to discount delayed rewards at much lower rates than nonhumans (e.g., Stevens & Stephens, 2010; Tobin & Logue, 1994). Rather than appeal solely to a biological explanation for cross-species differences in discounting, Paglieri (2013) suggested that economic variables such as the degree to which the costs of reward delays are experienced could also prove influential. In his analysis, Paglieri identified three types of costs experienced to some degree during reward delays: (1) direct costs of the delay (e.g., discomfort, boredom), (2) opportunity costs of the delay (i.e., loss of access to alternative sources of reinforcement), and (3) opportunity costs of the reward (i.e., zero utility of the reward until the delay has elapsed). In what Paglieri termed “operant” tasks (i.e., laboratory procedures typically used to assess discounting in nonhumans) Paglieri argued that delays preceding “larger–later” rewards are arranged so as to maximize the influence of each of these delay costs. In the typical discrete-choice arrangement, when a nonhuman subject responds (e.g., lever press, key peck) for a larger–later reward, a delay period is initiated before reward delivery. With the exceptions of putatively rewarding activities such as grooming and locomotion, there are no alternative sources of reinforcement available during the delay (Cost 2) and until the reward is eventually delivered, its utility is null (Cost 3). Although difficult to confirm experimentally, it is possible that nonhuman subjects experience aversive subjective effects during delay (Cost 1) that are analogous to the discomfort experienced during delays by humans (e.g., while waiting in line).

By contrast, in what Paglieri termed “questionnaire” tasks (henceforth, typical human delay discounting tasks) only the opportunity cost of the delayed reward itself (Cost 3) is implicit in the description of the choice alternatives (e.g., $5 now or $100 in 1 month). Because the durations of larger–later delays in typical human delay discounting tasks are substantially longer than those in operant tasks (e.g., months or years compared to minutes or seconds), it is likely that human participants assume that access to other rewards (e.g., other sources of money) will not be restricted during the delay (Cost 2), resulting in minimal direct costs of the delay (e.g., boredom or discomfort; Cost 1). When the phylogenetic discrepancy is conceptualized in this way, it is perhaps not surprising that humans discount delayed rewards much less steeply than do nonhumans. Recent human studies have shown, however, that when discounting is assessed using operant tasks in which larger–later reward delays are functionally equivalent to those experienced by nonhumans (i.e., they theoretically incorporate all of the aforementioned delay costs), delayed rewards are discounted orders of magnitude more steeply than is usually demonstrated in typical human delay discounting tasks (Jimura, Myerson, Hilgard, Braver, & Green, 2009; Jimura et al., 2011; Johnson, 2012; Rosati, Stevens, Hare, & Hauser, 2007, but see Genty, Karpel, & Silberberg, 2012). These findings provide support for Paglieri’s hypothesis that species differences reported in the delay discounting literature are, in part, the result of divergent methods, which, once approximately aligned, would eliminate the confound of differential delay costs and permit comparison of discounting performances solely on the basis of species differences between humans and nonhumans.

We believe that Paglieri (2013) has made an important theoretical contribution to our understanding of delay discounting and its assessment by proposing that costs incurred during larger–later reward delays are important determinants of discounting rates. However, we remain skeptical as to whether the three types of costs described by Paglieri are behaviorally distinguishable. In our opinion, Costs 2 and 3 are both opportunity costs involving restricted access to reinforcement (Cost 2 involves restriction of alternative reinforcers; Cost 3 involves temporary restriction of the delayed reinforcer). What Paglieri referred to as direct costs of delay (e.g., discomfort, boredom; Cost 1) may be interpreted as the subjective experience of opportunity costs rather than costs per se. In essence, Paglieri’s costs can be understood simply as opportunity costs during the reward delay.

Although the aforementioned studies have shown that humans discount substantially steeper in operant tasks than in typical human delay discounting tasks, the two task types have differed on dimensions other than opportunity cost (e.g., commodity type, delay durations, real vs. hypothetical). Thus, no study has explicitly manipulated opportunity cost during larger–later reward delays in order to determine effects on delay discounting rates, a critical step in evaluating Paglieri’s hypothesis. The present study investigated the effects of opportunity costs on rates of delay discounting. We chose to conduct the study using human participants primarily because results would have immediate utility in clinical and applied settings involving delayed rewards. We assessed discounting using a hypothetical task because we also wanted to arrange a continuum of opportunity costs ranging from unrestricted to severely restricted reinforcement during relatively long delays (e.g., 24 hrs). Ample evidence suggests that human participants discount hypothetical rewards in a manner similar to real rewards (Baker, Johnson, & Bickel, 2003; Bickel, Pitcock, Yi, & Angtuaco, 2009; Johnson & Bickel, 2002; Johnson, Bickel, & Baker, 2007; Lagorio & Madden, 2005; Madden, Begotka, Raiff, & Kastern, 2003; Madden et al., 2004; Matusiewicz, Carter, Landes, & Yi, 2013). This established finding suggests that responses provided by humans asked to consider hypothetical scenarios involving delayed rewards are likely to correspond to responses resulting from their actual experience of delayed rewards and associated opportunity costs.

Delay discounting assessments were conducted through Amazon’s crowdsourcing website, Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk is a recruitment and data collection service that allows researchers to advertise Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs), which are tasks that require minimal effort, but cannot be completed by a computer. MTurk is an appealing alternative to conducting in-person laboratory experiments for several reasons. Perhaps most importantly, MTurk is a highly efficient and cost-effective method for rapidly obtaining a substantial volume of data. Because the amount of work required to complete a HIT is typically low, compensation is scaled accordingly (e.g., $1), a feature that enables lower total costs than laboratory studies (Mason & Suri, 2012; Rand, 2012). MTurk is also valuable to researchers who are unable to access participants directly (for example, undergraduates), or who are interested in sampling from diverse populations (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010). Aside from practical benefits, MTurk studies are capable of successfully reproducing reliable descriptive and experimental phenomena with close correspondence to laboratory findings (e.g., Crump, McDonnell, & Gureckis, 2013; Simons & Chabris, 2012; Sprouse, 2011). These advantages have resulted in anonymous MTurk Workers contributing to research questions in a variety of disciplines including clinical science (e.g., Chen et al., 2014; Hao, Rusanov, Boland, & Weng, 2014; Kiefner-Burmeister, Hoffmann, Meers, Koball, & Musher-Eizenman, 2014; MacLean & Heer, 2013; Yu, Willis, Sun, & Wang, 2013), public health (e.g., Bell, McGlone, & Dragojevic, 2014; Carter, DiFeo, Bogie, Zhang, & Sun, 2014; Turner, Kirchhoff, & Capurro, 2012), psychology (e.g., Gardner, Brown, & Boice, 2012; Summerville & Chartier, 2013), and behavioral economics (e.g., Amir, Rand, & Gal, 2012; Bickel et al., 2012; Bickel et al., 2014; Epstein et al., 2014; Raihani & Bshary, 2012; Raihani, Mace, & Lamba, 2013).

Recently, Jarmolowicz and colleagues used MTurk to examine delay discounting (Jarmolowicz, Bickel, Carter, Franck, & Mueller, 2012). Discounting rates obtained using a monetary choice questionnaire (Kirby & Maraković, 1996) were significantly correlated with demographic variables known to vary with degree of discounting (e.g., age, education, smoking status). For the purposes of the present study, the Kirby and Maraković questionnaire was disadvantageous because it constrains estimates of discounting rates to a limited set of possible values. Instead, we obtained indifference points at a series of delays and estimated discounting rates via nonlinear regression, a method that allowed us to characterize data orderliness in addition to the shape of the discounting curve. Conducting the experiment in this manner also allowed us the opportunity to validate our use of MTurk for collecting delay discounting data by confirming empirically the presence of effects well-documented in the discounting literature. Specifically, we assessed (1) whether the data were better described by a hyperbolic decay equation or an exponential decay equation, (2) whether certain demographic variables (age, education) were negatively correlated with discounting rates, (3) whether larger delayed rewards were discounted less steeply than were smaller delayed rewards (i.e., the “magnitude effect”), (4) whether, in smokers, cigarettes were discounted more steeply than was money, (5) whether, in smokers, rates of discounting of money and cigarettes were correlated, and (6) whether smokers discounted delayed money more steeply than did nonsmokers. The inclusion of comparisons of commodity types (money vs. cigarettes) and drug use statuses (nonsmokers vs. smokers) allowed us the opportunity to explore interactions between these variables and degree of opportunity cost.

Methods

Participants

Individuals registered on MTurk were recruited to serve as participants through their completion of a HIT. In order to view and accept the HIT, Workers were required to have a 95% or higher approval rating from previously submitted HITs (individuals administering HITs provide feedback on Workers upon completion of a HIT), and residence in the United States (confirmed during initial registration on MTurk). Participation was voluntary and anonymous (no name or IP address recorded). This implied consent study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

During the initial launch (8/13/13-8/15/13), 103 participants completed the survey, which was available regardless of smoking status. Because only 21 of these participants self-identified as smokers, the survey was relaunched (8/15/13-8/17/13) with recruitment limited to smokers through the use of a screening questionnaire so that the sample contained comparable numbers of smokers and nonsmokers; 64 participants completed the survey during this period. Smokers recruited through these first two launches are henceforth referred to as “Batch 1.” As described below, both smokers and nonsmokers completed a money discounting assessment. Unlike nonsmokers, however, smokers also completed a cigarette discounting assessment. Both nonsmokers and smokers were paid $1 with the chance to earn a $1 bonus payment (see Procedure for criteria). Thus, for smokers, the number of questions in the survey was approximately twice that completed by nonsmokers despite the same pay, a between-group difference that we believed could result in greater attrition of smokers. To address this potential confound, a third launch was conducted (9/2/13-9/5/13) in which 85 self-identified smokers qualified through the screening questionnaire and completed only the money delay discounting assessment (henceforth, “Batch 2”). Compensation for these participants was identical to that of prior participants ($1 with a $1 possible bonus). Overall, 252 participants completed the survey.

Materials

All surveys were hosted online by Qualtrics (Provo, UT). The screening questionnaire consisted of a description of the survey (e.g., purpose of the study, confidentiality and anonymity of responses, compensation structure) followed by questions related to demographic variables including age, sex, race, ethnicity, household income, education, and smoking status. Although qualification was contingent solely on smoking status during the second and third launches, these other questions were included to obscure this inclusion criterion. If an individual qualified for participation, he or she was given a code to access the password-protected survey.

The survey consisted of demographic questions and two delay discounting assessments (described below). Participants identifying as smokers (i.e., “yes” in response to “Do you smoke cigarettes?”) were administered the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD; formerly known as the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; Fagerström, 2012; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). Smokers (Batch 1) were also asked to calculate the number of individual cigarettes of their preferred brand they could purchase for $10 and $100. These money-equivalent values were used to assess cigarette discounting immediately following the money discounting assessment.

Money discounting

Delay discounting was assessed via hypothetical framing conditions differing descriptively in terms of the opportunity costs incurred during a delay to a monetary reward (see Table 1). Four delay framing conditions, termed “Free,” “Return,” “Browse,” and “Wait,” were presented in a randomized order. Prior to encountering each delay framing condition, participants read the following description of a hypothetical choice between receiving money now or later:

For each of the next 16 questions, imagine the following hypothetical (pretend) scenario: You are presented with a choice between money now or later. For the money now option, the money is deposited automatically into your bank account now and you are immediately free to pursue other activities. For the money later option, [framing condition-specific description provided in Table 1]. Your job is to use the slider tool to tell us the amount of money that you would like to receive immediately that would make you feel JUST AS GOOD as you would if you were to receive money after the specified time. Although the scenarios are pretend, we ask that you consider each scenario as if it was real and as if it was the only scenario you would face today. Finally, when considering each scenario, you should take into account your financial circumstances (e.g., current account balance, rent or bills due). You will now take a short quiz to confirm your understanding of these instructions.

Table 1.

Descriptions of delayed reward option for each delay framing condition.

| Condition | Description |

|---|---|

| Free | “[Y]ou don’t have to wait at

the computer or return to the computer to have the (money deposited into your bank account/cigarettes presented to you). Instead, you are immediately free to pursue other activities. After the specified time, the (money is deposited automatically into your bank account/cigarettes are presented to you), regardless of where you are at that time.” |

| Return | “[Y]ou are immediately free to pursue

other activities. After the specified time, the (money is deposited into your bank account/cigarettes are presented to you). However, you must be present at your computer when time has elapsed to confirm the (deposit/delivery of the cigarettes). You also do not have access to any sort of timepiece (e.g., watch) during the specified time.” |

| Browse | “[Y]ou must wait at your computer for

the entire time specified in the question. However, you can leave the survey and browse the Internet except for Mechanical Turk. All other sources of entertainment (e.g., cell phone, books, music) are unavailable. You cannot smoke cigarettes or sleep. You are free to leave only briefly to eat, drink, or use the restroom. After the specified time, the (money is deposited automatically into your bank account/cigarettes are presented to you).” |

| Wait | “[Y]ou must wait at your computer for

the entire time specified in the question. You cannot leave the survey and therefore cannot use the computer for other activities. All other sources of entertainment (e.g., cell phone, books, music) are unavailable. You cannot smoke cigarettes or sleep. You are free to leave only briefly to eat, drink, or use the restroom. After the specified time, the (money is deposited automatically into your bank account/cigarettes are presented to you).” |

Immediately after reading the description, participants completed a five-question, multiple-choice quiz. Quiz questions assessed participants’ understanding of the reward type relevant to the current discounting assessment (e.g., money, cigarettes), the consequences associated with “now” and “later” options, how to use the slider tool, and what factors should be taken into account when answering questions (e.g., financial circumstances). If a question was answered incorrectly, the participant was asked to try again; this process continued indefinitely until the correct answer was submitted.

Within each delay framing condition, discounting of two magnitudes ($10 & $100) was assessed separately in a randomized order (i.e., $10 magnitude followed by the $100 magnitude, or vice versa). The delays within each magnitude were 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 hr, 3 hr, 6 hr, 12 hr, and 24 hr. Delays were always presented in an ascending order. Each delay question was presented individually along with the “money now” and “money later” descriptions for the current delay framing condition. Below these descriptions was an elicitation prompt in the following format: “Receiving X after D makes me feel JUST AS GOOD as:” where X was equal to the delayed money amount ($10 or $100) and D was equal to the delay. An interactive slider tool displayed below the elicitation prompt allowed participants to designate an amount in “dollars now” that was subjectively equivalent to the discounted value of the delayed amount. Numerical values ranging from zero to the delayed amount were displayed above the slider tool in increments corresponding to tenths of the delayed amount. The default position of the slider was always the delayed amount (rightmost position). As participants moved the slider, a value rounded to the nearest cent was displayed to the right of the slider. Once the participant had moved the slider to his/her desired location, he/she clicked a button to submit the corresponding value and advance to the next question. With the exception of distractor questions (described below), participants could not advance to the next question unless the slider had been moved from its default position.

Cigarette discounting

With the exception of the following modifications, the cigarette discounting assessment was identical to the money discounting assessment. First, cigarettes replaced money as the discounted commodity (see Table 1), and as such, only smokers (Batch 1) completed this section. Second, rather than taking their financial circumstances into account when considering each framing condition, participants were asked to take into account their current smoking patterns. Finally, as described below, the response topography differed slightly from that of the slider tool used in the money discounting assessment.

For each delay question, the following elicitation prompt was presented immediately below the “cigarettes now” and “cigarettes later” descriptions: “Receiving X cigarettes after D makes me feel JUST AS GOOD as receiving right now the number of cigarettes in the text box below. This number below must be less than or equal to X.” In this prompt, X was equal to the money-equivalent cigarette value calculated earlier in the survey by the participant and D was equal to the delay. Participants entered into a text box located below the prompt the number of cigarettes receivable immediately that would be subjectively equivalent to receiving the delayed amount.

Procedure

The HIT was advertised on MTurk with the title, “Tell us how you feel about hypothetical (pretend) reward scenarios. 30-minute survey with $1 bonus possible.” Clicking the hyperlink to the survey opened a new tab in the participant’s browser. Participants were instructed to complete the survey in one sitting. Within the survey and following demographic questions, the money discounting assessment always preceded the cigarette discounting assessment (Batch 1 only). At the conclusion of the survey, participants were instructed to generate and submit a 6-digit alphanumeric code. Upon returning to MTurk to submit the completed HIT, participants were prompted to enter this code into a text box to verify that they had completed the survey. All participants with matching codes received $1 as base pay for submitting the survey and completing the HIT.

Three tactics were employed to improve participant attention and engagement or allow us to detect poor attention and engagement. First, in the HIT and survey descriptions, participants were instructed that paying attention during the survey and answering questions carefully could potentially result in a $1 bonus payment. Second, during the survey, occasional distractor questions instructed participants to provide a specific response to demonstrate that they had paid attention (e.g., “move slider to zero”). Distractor questions were distributed equally among delay framing conditions (i.e., one per framing condition) with the exception of the Return framing condition for the cigarette discounting assessment, which did not contain a distractor question due to experimenter error. Finally, at the conclusion of the survey, participants were asked if they had paid attention and whether the experimenters should use their data. A participant was deemed eligible for a $1 bonus payment if (a) he/she provided appropriate responses to distractor questions, and (b) his/her discounting data were judged to be systematic (described below).

Data Analysis

Indifference points were calculated as a proportion of the delayed reward magnitude to facilitate comparisons across different magnitudes and commodities. Participants whose data indicated inattention to survey questions (i.e., failed ≥ 1 distractor question) were excluded from further analysis. Criteria based on those proposed by Johnson and Bickel (2008) were applied to indifference points to identify deviations from systematic discounting. The first criterion was that, beginning with the second delay (10 min), no indifference point could exceed the immediately preceding indifference point by more than 20%. The second criterion was that the indifference point at the final delay (24 hr) could not exceed the indifference point at the first delay (5 min) by more than 10%. Unlike the distractor questions, these criteria were not used as a basis for data exclusion. Rather the criteria were used to determine if a bonus was to be awarded and to characterize the orderliness of the data.

Nonlinear regression was used to fit the hyperbolic decay model (Mazur, 1987) to indifference points (GraphPad Prism version 6.03 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA):

| (1) |

In Equation 1, IND is the indifference point expressed as a proportion of the delayed reward amount, D is the delay to receipt of the reward, and k, a free parameter, quantifies discounting rates. Because D was coded in the unit of hours in the nonlinear regressions, resulting k values carried the units of hours−1. For comparative purposes, an exponential decay model was also fit to the data:

| (2) |

Variables in Equation 2 are defined as in Equation 1, and e represents Euler’s number. Root mean squared errors (RMSE) from hyperbolic (Eq. 1) and exponential (Eq. 2) model fits were compared across reward magnitudes and delay framing conditions for each commodity. Compared to R2, RMSE is a superior measure of goodness-of-fit because it is calculated irrelative of error accounted for by the mean of the data, thereby avoiding greater stringency for lower discounting rates (i.e., a systematic positive correlation between R2 and discounting rates; Johnson & Bickel, 2008).

Estimates of discounting rates (k) from Equation 1 were nonnormally distributed and were log10 transformed, which improved the normality of the data, prior to subsequent analyses. For all participants, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA; PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0) was used to examine the within-subject effects of delay framing condition and reward magnitude on money discounting. RM ANOVA was also performed exclusively using data from smokers (Batch 1) and with the addition of commodity (money vs. cigarettes) as a within-subject factor. Finally, to examine the between-subject effect of smoking status on money discounting, nonsmokers, Batch 1 smokers, and Batch 2 smokers were first compared demographically using Chi-square tests for categorical variables (sex, race, ethnicity) and one-way ANOVA for interval variables (age) and ordinal variables (income, education). Significant demographic differences were addressed via post hoc matching prior to conducting a mixed-model ANOVA. That is, individuals were removed from either group in order to minimize differences in demographics between groups. Importantly, this selection was based solely on demographics and not on dependent measures (i.e., discounting data). In the event of violations of assumed sphericity, degrees of freedom were corrected according to the Greenhouse-Geisser method. For all tests, alpha was set at .05. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni corrections to alpha. Effect sizes were calculated as generalized eta squared.

Spearman rank correlations compared discounting rates between delay framing conditions within each commodity. Spearman rank correlations were also conducted between money and cigarette discounting rates within each delay framing condition, as well as between discounting rates for both commodities and participant age and education.

Results

Data Orderliness

All 252 participants who completed the main survey indicated that they had paid attention during the survey and that their data should be included in any analyses. However, 50 (19.8%) participants failed at least one distractor question; their data were excluded listwise from all analyses.

The remaining 202 participants—66 nonsmokers, 66 Batch 1 smokers, and 70 Batch 2 smokers—provided 2144 sets of indifference points. One hundred and eighty-three (8.5%) sets failed the first criterion (i.e., no indifference point > 20% of immediately preceding indifference point) and 192 (8.9%) sets failed the second criterion (i.e., final indifference point no greater than 10% that of the first indifference point).

Shape of Discounting Functions

Table 2 shows the number of sets of indifference points best fit by Equations 1 and 2 for each magnitude-delay framing condition combination. For 12 sets of money-discounting data (five participants [four smokers]), neither model converged on a fit. These cases were treated as ties for the purpose of the present comparison, but were removed from subsequent statistical analyses because nonlinear regression was unable to estimate k. In all 16 magnitude-delay framing conditions, more individual participant data sets were better described by (i.e., lower RMSE) Equation 1 than Equation 2. For 13 of the 16 conditions, the majority of participants (i.e., ≥ 50%) were best fit by Equation 1 (i.e., hyperbolic RMSE < exponential RMSE). For the three condition combinations in which ties predominated ($10 & $100 Money and $100 Cigarettes in the Free delay framing condition), Equation 1 provided a superior fit for more participants than Equation 2.

Table 2.

Number of sets of indifference points best fit by Equations 1 and 2

| Money (n = 202) | Cigarettes (n = 66) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Magnitude | Hyp. (%) | Exp. (%) | Tie (%) | Hyp. (%) | Exp. (%) | Tie (%) |

| Free | $10 $100 |

82 (40.6) 77 (38.1) |

17 (8.4) 21 (10.4) |

103 (51.0) 104 (51.5) |

34 (51.5) 29 (43.9) |

8 (12.1) 8 (12.1) |

24 (36.4) 29 (43.9) |

| Return | $10 $100 |

136 (67.3) 133 (65.8) |

37 (18.3) 33 (16.3) |

29 (14.4) 36 (17.8) |

44 (66.7) 39 (59.1) |

16 (24.2) 17 (25.8) |

6 (9.1) 10 (15.2) |

| Browse | $10 $100 |

101 (50.0) 106 (52.5) |

78 (38.6) 73 (36.1) |

23 (11.4) 23 (11.4) |

36 (54.5) 36 (54.5) |

23 (34.8) 22 (33.3) |

7 (10.6) 8 (12.1) |

| Wait | $10 $100 |

106 (52.5) 112 (55.4) |

70 (34.7) 71 (35.1) |

26 (12.9) 19 (9.4) |

41 (62.1) 36 (54.5) |

20 (30.3) 23 (34.8) |

5 (7.6) 7 (10.6) |

Effects of Opportunity Costs on Money Discounting

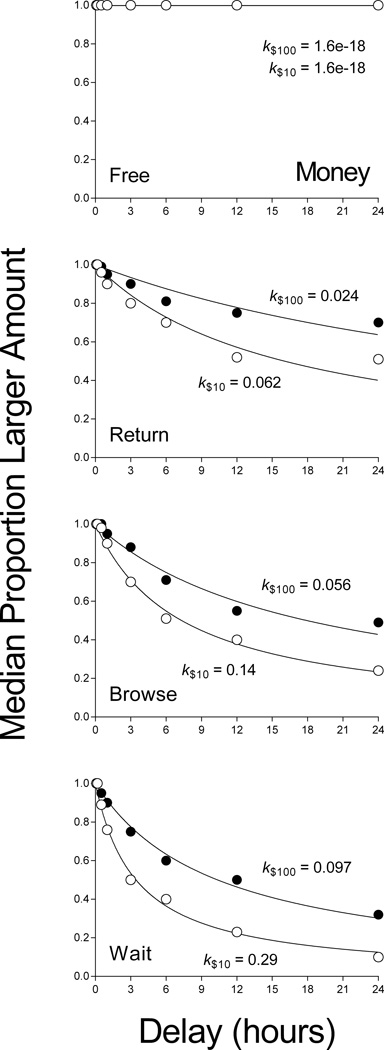

Figure 1 depicts group median indifference points (i.e., immediate money amount equivalent to the delayed money amount) for each of the four money discounting delay framing conditions for 202 participants, regardless of smoking status. Delay frame plots are arranged from top (Free) to bottom (Wait) in order of increasing opportunity costs associated with delay. Best-fit curves (Eq. 1) and resulting k estimates are also shown for each set of median indifference points. With the exception of the Free delay framing condition, median indifference points generally decreased in response to increases in delay to the larger money amount. Across the four delay framing conditions, rates of discounting increased as a function of increased opportunity costs incurred during the larger–later delay period. A magnitude effect (i.e., larger delayed magnitudes discounted less steeply than smaller delayed magnitudes) was also evident in each delay framing condition with the exception of the Free delay framing condition.

Figure 1.

Consistent with these observations, a RM ANOVA comparing log k values (n = 197) revealed a significant interaction between delay framing condition and reward magnitude, F(2.64, 517.65) = 4.82, p < .01, η2G < .01. To further explore the interaction, we performed separate RM ANOVAs post hoc to compare log k values at each delay framing condition within each magnitude; alpha was adjusted for the number of tests (.05/2 = .025). A significant main effect of delay framing condition was observed for the $10 magnitude, F(2.23, 436.76) = 131.05, p < .001, η2G = .21, as well as for the $100 magnitude, F(2.53, 495.59) = 110.16, p < .001, η2G = .19. Of the post hoc pairwise comparisons conducted between delay framing conditions, all comparisons involving the Free and Return conditions were significant (log kFree < log kReturn & log kBrowse & log kWait; log kReturn < log kBrowse & log kWait; all p values < .001). Browse and Wait log k values were not significantly different for either magnitude (p values ≥ .13).

Within-subject Spearman rank correlations examined the correspondence between money discounting rates obtained in each combination of delay framing condition and reward magnitude (Table 3). Among the 197 participants included in this analysis, discounting rates were positively and significantly correlated in 24 out of 28 cases (all p values < .01). The remaining 4 cases in which significant correlations were not observed exclusively involved both magnitudes from the Free and Wait delay framing conditions (all p values ≥ .07).

Table 3.

Between-condition Spearman rank correlation matrices for money and cigarette log k values

| Money (n = 197) | Cigarettes (n = 65) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Magnitude | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Free | $10 $100 |

- .79 |

- | - .90 |

- | ||||||||||||

| Return | $10 $100 |

.40 .32 |

.28 .45 |

- .67 |

- |

.57 .57 |

.45 .51 |

- .88 |

- | ||||||||

| Browse | $10 $100 |

.30 .30 |

.21 .37 |

.66 .54 |

.43 .55 |

- .70 |

- |

.38 .43 |

.32 .43 |

.73 .69 |

.75 .79 |

- .83 |

- | ||||

| Wait | $10 $100 |

.11 .12 |

.02 .13 |

.56 .48 |

.34 .40 |

.62 .54 |

.50 .59 |

- .65 |

- |

.43 .45 |

.36 .35 |

.52 .58 |

.56 .66 |

.74 .68 |

.62 .69 |

- .81 |

- |

Note: Italicized text indicates p < .01. Bolded text indicates p < .001.

Effects of Commodity Type

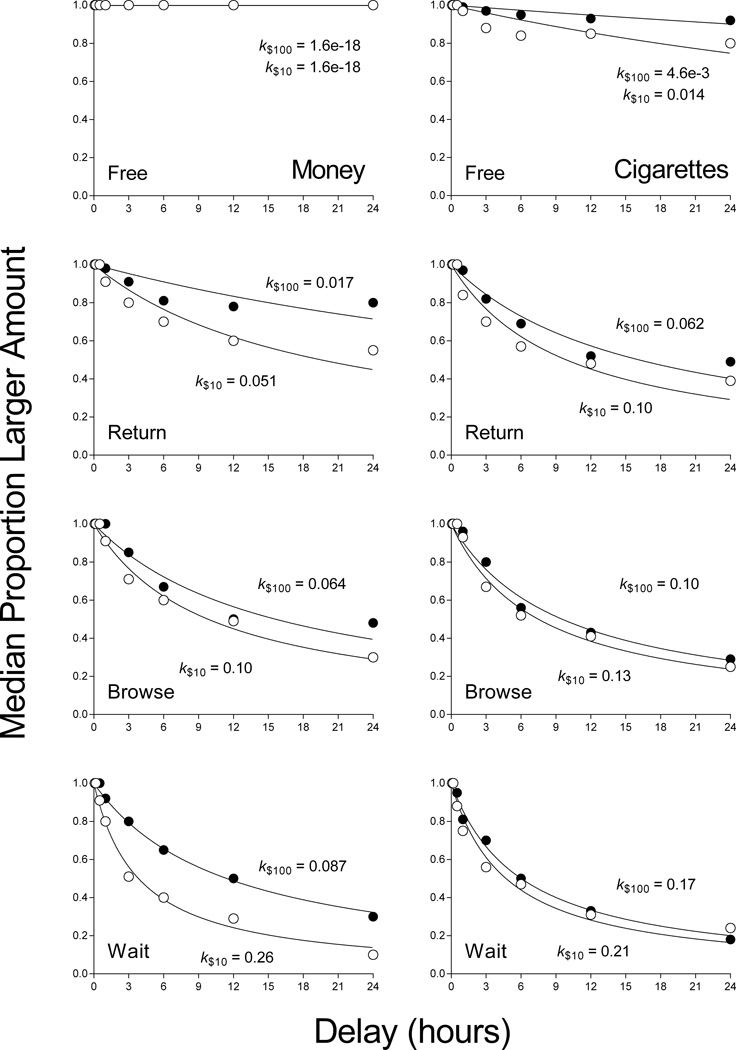

Figure 2 depicts group median indifference points with best-fitting curves for each magnitude, delay framing condition, and commodity for Batch 1 smokers only (n = 66). With the exception of median indifference points for money from the Free delay framing condition, median indifference points decreased for both money and cigarettes as a function of delay until receipt of the commodity. As observed in the money discounting assessment, rates of cigarette discounting increased as a function of the increasing opportunity costs associated with the delay period (i.e., across delay framing conditions). In almost all of the commodity-delay framing condition combinations, larger magnitudes were discounted less than smaller magnitudes (i.e., k$100 < k$10). Finally, delayed money was discounted less steeply than delayed cigarettes of equivalent monetary value in seven out of eight comparisons (i.e. all except Wait $10).

Figure 2.

These descriptive findings were confirmed statistically by the presence of significant two-way interactions involving commodity and delay framing condition, F(1.94, 124) = 4.14, p < .02, η2G = .01, commodity and reward magnitude, F(1, 64) = 8.17, p < .01, η2G < .01, and delay framing condition and reward magnitude, F(2.68, 171.66) = 2.88, p < .05, η2G < .01. The three-way interaction between these factors was not significant (p = .23). Separate RM ANOVAs were conducted for money and cigarette discounting to examine the effect of delay framing condition within each commodity (alpha = .025). For money discounting, significant main effects of reward magnitude (log k$100 < log k$10), F(1, 64) = 16.14, p < .001, η2G = .02, and delay framing condition, F(2.22, 142.12) = 53.61, p < .001, η2G = .21, were detected. No significant interaction between these two factors was observed for money discounting (p = .18). Post hoc pairwise comparisons again revealed significant differences (log kFree < log kReturn & log kBrowse & log kWait; log kReturn < log kBrowse & log kWait; all p values < .01) between all but the Browse–Wait delay framing conditions (p = .14). For cigarette discounting, only a significant main effect of delay framing condition was observed, F(1.94, 124.40) = 15.82, p < .001, η2G = .04. Neither a significant magnitude effect (p = .64) nor a magnitude by delay framing condition interaction (p = .05) were present, although the latter trended toward significance. Unlike money discounting, only post hoc pairwise comparisons involving the Free condition were significant (log kFree < log kReturn & log kBrowse & log kWait; p values < .01).

Table 3 displays Spearman rank correlations comparing cigarette discounting rates from each delay framing condition and reward magnitude combination. Among the 65 participants included in this analysis, discounting rates were positively and significantly correlated in all 28 cases (all p values ≤ .01). To determine if the higher number of significant between-condition correlations for cigarettes was due to the commodity type or the subgroup of interest (nonsmokers vs. smokers), Spearman rank correlations were also conducted for money discounting rates across all conditions for Batch 1 smokers only. Consistent with the initial analyses performed using data from all participants, significant positive correlations between conditions were identified in 22 of the 28 cases for smokers (Free $100 vs. Return $10 and Browse $10 were no longer significant, all p values ≥ .05; statistical results not shown).

Correlations between Demographic Variables and Discounting Rates

Spearman rank correlations describing the relation between rates of money discounting (log k) and age were negative in all eight magnitude-delay framing condition combinations, ranging from −.03 to −.24 (see Table 4). Only money discounting rates from the $10 magnitude (ρ = −.21, p < .01) and the $100 magnitude (ρ = −.24, p < .01) from the Free delay framing condition and the $10 magnitude from the Wait condition (ρ = −.16, p = .03) were significantly correlated with age. By contrast, in none of the magnitude-delay framing combinations for cigarettes was discounting significantly correlated with age (all p values ≥ .39).

Table 4.

Spearman rank correlations between money log k values and age or education (n = 197) or cigarette log k values (Batch 1 smokers; n = 65)

| Age | Education | Cigarette log k | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Magnitude | Spearman ρ | p | Spearman ρ | p | Spearman ρ | p |

| Free | $10 $100 |

−.21 −.24 |

<.01 <.01 |

−.16 −.24 |

.02 <.01 |

.31 .40 |

.01 <.01 |

| Return | $10 $100 |

−.09 −.03 |

.22 .69 |

−.07 −.11 |

.33 .14 |

.47 .40 |

<.01 <.01 |

| Browse | $10 $100 |

−.12 −.05 |

.10 .49 |

−.01 −.06 |

.92 .38 |

.37 .28 |

<.01 .03 |

| Wait | $10 $100 |

−.16 −.09 |

.03 .22 |

.03 .02 |

.65 .77 |

.45 .34 |

<.01 <.01 |

Spearman rank correlations between money discounting rates and education were negative in six out of eight magnitude-delay framing condition combinations, the exceptions being the $10 and $100 Wait delay framing conditions (Table 4). Similar to the correlations involving age, only money discounting rates from the $10 magnitude (ρ = −.16, p = .02) and the $100 magnitude (ρ = −.24, p < .01) from the Free delay framing condition were significantly correlated with education. Likewise, in none of the magnitude-delay framing combinations for cigarettes was discounting significantly correlated with education (all p values ≥ .18).

Correlations between Money and Cigarette Discounting Rates

Spearman rank correlations between log-transformed k values for both commodities were assessed in each of the eight magnitude-delay framing condition combinations (Table 4). Discounting rates for money and cigarettes were significantly and positively correlated in all cases (all p values ≤ .03).

Effects of Smoking Status

Before assessing the effect of smoking status on money discounting, demographic characteristics of nonsmokers, Batch 1 smokers, and Batch 2 smokers were compared statistically. With the exception of education which differed significantly between the groups (F [2, 199] = 3.11, p < .05, nonsmokers > Batch 2 > Batch 1), there were no significant demographic differences between the three groups. Subgroups were selected from among the three groups—55 nonsmokers, 59 Batch 1 smokers, and 61 Batch 2 smokers—without regard to the outcome measures so that the subgroups matched on education and no longer differed significantly (p = .49); matching did not affect other demographic differences, which remained nonsignificant (all p values ≥ .31). Demographic characteristics (postmatching) for the three groups are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Participant demographics for smoking status analysis

| Characteristic | Nonsmokers (n = 55) |

Smokers (Batch

1) (n = 59) |

Smokers (Batch

2) (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 35.6 (13.4) | 35.5 (10.7) | 35.6 (12.0) |

| Sex (% Female) | 53 | 61 | 57 |

| Race (% Caucasian/White) | 82 | 92 | 87 |

| Ethnicity (% Non Hispanic) | 91 | 88 | 92 |

| Annual Income (%) | |||

| Under $25,000 | 29 | 34 | 32 |

| $25,000-$34,999 | 15 | 19 | 14 |

| $35,000-$49,999 | 18 | 20 | 19 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 15 | 17 | 20 |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 13 | 8 | 15 |

| $100,000-$124,999 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| $125,000-$149,999 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Over $150,000 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Education (%) | |||

| No high school diploma | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| High school graduate, diploma or equivalent (GED) | 9 | 15 | 15 |

| Trade/technical/vocational training after high school | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Some college credit, no degree | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| Associate’s degree | 11 | 14 | 15 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 33 | 27 | 31 |

| Master’s degree | 9 | 7 | 10 |

| Professional/doctorate degree | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Smoking duration, years, mean (SD) | - | 15.5 (11.8) | 17.1 (12.2) |

| Cigarettes/day, mean (SD) | - | 12.8 (7.2) | 12.7 (8.3) |

| FTCD Score, mean (SD) | - | 4.0 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.7) |

Note. GED = General Educational Development; FTCD = Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding error.

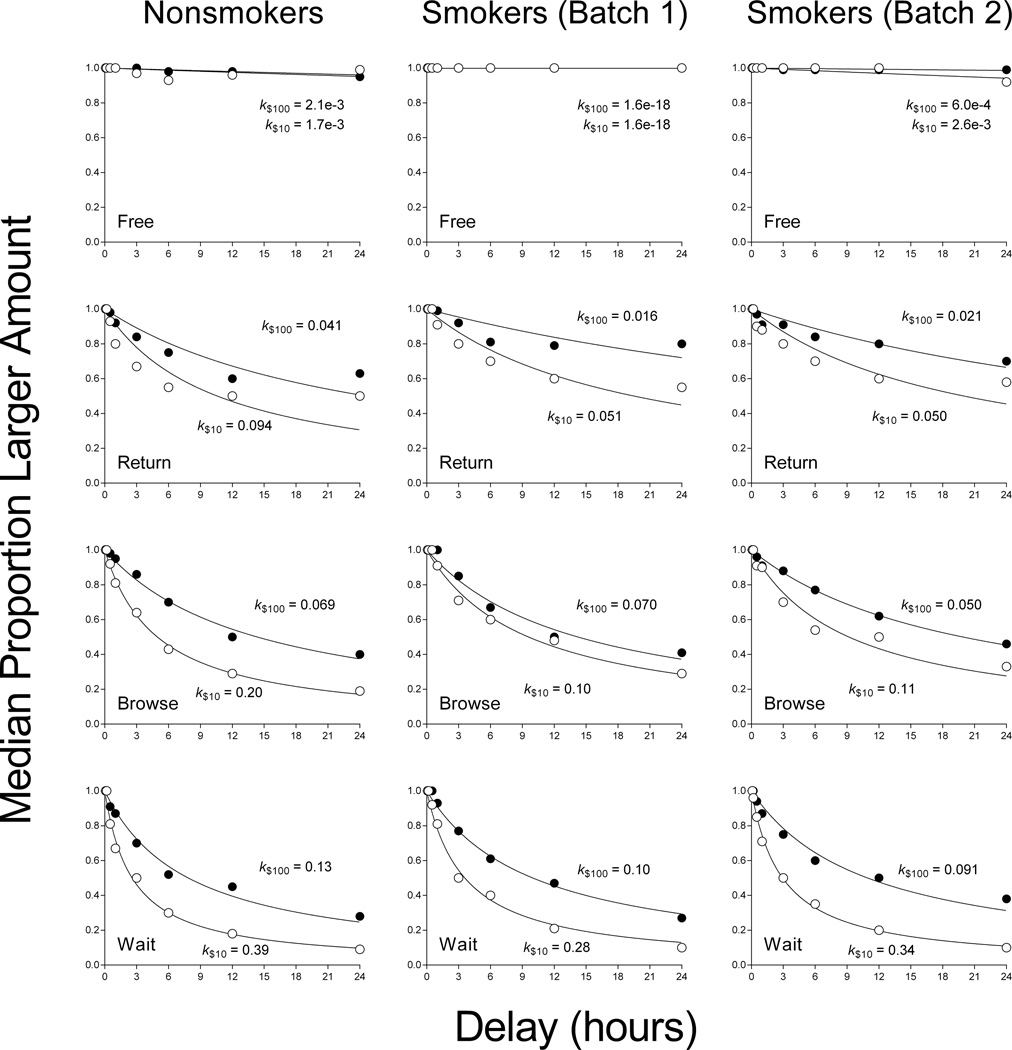

Figure 3 depicts median group indifference points and best-fitting curves for each magnitude and delay framing condition combination of money discounting for the three groups. As in previous analyses, without exception, rates of discounting increased across the four delay framing conditions as a function of increased opportunity costs incurred during the larger–later delay period. Additionally, the magnitude effect was observed in almost every magnitude-framing condition combination (the exception being the Free delay framing condition for Batch 1 smokers in which median data showed a ceiling effect for indifference points at both magnitudes). With respect to the influence of smoking status on these effects, nonsmokers consistently discounted delayed money more steeply than smokers, regardless of delay framing condition or reward magnitude. These median differences were apparent not only between nonsmokers and Batch 1 smokers, but also between nonsmokers and Batch 2 smokers. Smokers, regardless of whether they had completed one or two discounting assessments, discounted delayed money nearly identically in terms of median k estimates.

Figure 3.

Median differences were consistent with the results of the mixed model ANOVA, which detected a significant main effect of smoking status, F(2, 172) = 4.36, p = .01, η2G = .02. Because this between-subject factor did not interact significantly with any within-subject factors (all p values ≥ .65), post hoc pairwise comparisons were easily interpreted: Nonsmokers discounted delayed money significantly more steeply than Batch 1 (log kNonsmoker > log kBatch 1; p = .01), but not Batch 2 (p = .55), smokers. Discounting of smokers did not differ significantly between Batch 1 and Batch 2 (p = .29).

We conducted an auxiliary mixed model ANOVA restricting Batch 2 to only heavy smokers (i.e., ≥ 20 cigarettes/day; n =15). Fifteen nonsmokers were selected who demographically matched these 15 heavy smokers. Differences between smokers and nonsmokers were not significant (p = .82).

Discussion

The present study determined the effects of opportunity costs on delay discounting rates. In doing so, we confirmed Paglieri’s (2013) hypothesis that opportunity costs incurred during larger–later reward delays increase rates at which delayed rewards are discounted. Moreover, we reproduced reliable discounting findings from the research literature, including superior fit of the data to the hyperbolic decay equation (compared to the exponential decay equation), significant correlations between demographic variables and discounting rates, the magnitude effect, domain-specific discounting with a drug of abuse being discounted more than equivalent amounts of money, and cross-commodity correlations in discounting rates. Despite these positive findings, the study did not reproduce the finding that smokers discount delayed rewards more than nonsmokers. In the following sections, we discuss in the context of the strengths and weaknesses afforded by the methodological approach the current findings and their implications for future studies aimed at evaluating opportunity costs of delayed rewards.

The primary finding of the present study was that by asking participants to consider a range of framing conditions in which only opportunity costs were systematically varied, we were able to observe corresponding changes in rates of delay discounting across the same series of reward delays, regardless of reward magnitude or commodity type. In the Free delay framing condition, i.e., the condition most analogous to typical tasks commonly administered to human participants, discounting rarely occurred. That is, when participants were informed explicitly that delivery of the reward did not depend on their behavior (e.g., returning to or waiting in one location to collect the reward), median data showed the delayed reward retained its full value or was discounted minimally (> 86% value) at the longest delay assessed (24 hr), a finding consistent with previous research (e.g., $100 retained > 90% of its value at a 24-hr delay using both hypothetical and potentially real rewards in Johnson & Bickel, 2002). By contrast, the prospect of having to return to one’s computer at a later time to confirm delivery of the delayed reward (the Return condition) was sufficient to induce more substantial discounting. Increasingly stringent opportunity costs were imposed in the Browse and Wait delay framing conditions in which participants were asked to imagine remaining in their current location for the duration of the larger–later delay. These framing conditions were designed to model opportunity costs associated with operant tasks and, as such, significantly greater rates of delay discounting were observed in these two delay framing conditions relative to the Free and Return delay framing conditions. Across all of the delay framing conditions investigated, we observed, without exception, increases in median discounting rates when opportunity costs were increased, a pattern of findings demonstrating empirically the deleterious effects that opportunity costs have on one’s valuation of delayed rewards.

By design, we attempted to reproduce six ubiquitous features of delay discounting in an effort to validate the use of MTurk. The first of these features was the superior fit of a hyperbolic decay equation (Mazur, 1987) to obtained indifference points compared to the fit of an exponential decay equation (Samuelson, 1937). Although alternative discounting equations have been proposed in recent years (e.g., Green & Myerson, 2004; Killeen, 2009; McClure, Ericson, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen, 2007; Rachlin, 2006), the hyperbolic decay equation is the simplest formulation (i.e., fewest free parameters) with the ability to readily account for preference reversals (e.g., Ainslie, 1975; Loewenstein & Thaler, 1989) and, as a result, it has been applied extensively across species and commodities (Madden & Bickel, 2010). In the present study, the hyperbolic decay equation described a greater percentage of sets of indifference points than did the exponential decay equation in all 16 magnitude-commodity-framing condition combinations. The finding that hyperbolic discounting predominates in our data set relative to exponential discounting provides some support for our use of an elicitation procedure to generate indifference points. By contrast, the Kirby and Maraković (1996) monetary choice questionnaire assumes hyperbolic discounting and therefore does not enable researchers to assess empirically the possibility of exponential discounting.

The second discounting feature of interest was the common finding in human studies that demographic variables such as age and education are significantly and negatively related to discounting rates for delayed money (e.g., Bickel et al., 2012; de Wit, Flory, Acheson, McCloskey, & Manuck, 2007; Green, Fry, & Myerson, 1994; Green, Myerson, Lichtman, Rosen, & Fry, 1996; Jarmolowicz et al., 2012; Jaroni, Wright, Lerman, & Epstein, 2004; Jimura et al., 2011; Olson, Hooper, Collins, & Luciana, 2007; Scheres et al., 2006; Yoon et al., 2007). Interestingly, while our data also revealed negative correlations between these demographic variables and money discounting rates, statistical significance of these correlations was almost entirely exclusive to the Free delay framing condition. Conversely, correlations between these variables and cigarette discounting rates were not consistently negative or significant in any case. These compelling findings suggest that the oft-cited relations between demographic variables (e.g., age, education) and delay discounting may in fact be limited to assessments involving money under conditions involving little or no opportunity cost.

A third reliable feature of delay discounting is that larger delayed rewards are discounted less steeply than smaller rewards (i.e., the magnitude effect). Both visual and statistical analyses confirmed the presence of the magnitude effect in the present study, but with two important exceptions. First, the magnitude effect was rarely observed in the Free delay framing condition, a finding which is readily explained by a ceiling effect on indifference points and a maximum delay (24 hr) that is much shorter than typically used in studies used to show the magnitude effect. Second, unlike money discounting, there was no statistically significant difference between the discounting of the $10 and $100 cigarette magnitudes (i.e., money-equivalent amounts of cigarettes). It is worth noting, however, that the interaction between cigarette magnitude and delay framing condition was nearly significant. Indeed, the largest of these magnitude differences occurred in the Free delay framing condition, a finding consistent with studies reporting the magnitude effect with cigarettes in smokers (Baker et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2007). By comparison, discounting of the two magnitudes was not as differentiable in conditions associated with opportunity costs, suggesting that opportunity costs may supersede the effect of magnitude for consumable commodities (but see Experiment 3 of Jimura et al., 2009, for a reported magnitude effect with liquid rewards in an operant task with humans). Further research is needed to reconcile these seemingly incongruous findings.

A fourth finding from the discounting literature that we attempted to reproduce is that consumable rewards are generally discounted more steeply than money (e.g., Bickel et al., 2011; Charlton & Fantino, 2008; Odum, Baumann, & Rimington, 2006; Odum & Rainaud, 2003; Weatherly, Terrell, & Derenne, 2010). This outcome has also been documented in cigarette smokers, for whom delayed cigarettes are discounted more steeply than money (Baker et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2007; Odum & Baumann, 2007). Consistent with these studies, we also observed steeper discounting of cigarettes than money in smokers. However, commodity type did not interact significantly with delay framing condition, suggesting that relative differences between cigarette and money discounting rates were unaffected by the imposition of opportunity costs. Additional work is needed to verify this finding, perhaps through the use of operant tasks in humans given the availability of amenable procedures (e.g., Jimura et al., 2009; Johnson, 2012; Reynolds & Schiffbauer, 2004). Effects of opportunity costs on discounting of delayed primary versus generalized conditioned reinforcement could also be investigated in nonhumans. Interestingly, pigeons have been shown to choose larger–later over smaller–sooner rewards in the context of token reinforcement (Jackson & Hackenberg, 1996), a preference opposite the one typically observed when choice is between immediate and delayed food rewards. A similar approach could compare preference when rates of alternative reinforcement available during reward delays (i.e., opportunity costs) are systematically manipulated for each reinforcer type.

Along these same lines, a fifth finding is that within-subject discounting rates of multiple commodities are often significantly correlated (e.g., Bickel et al., 2011; Friedel, DeHart, Madden, & Odum, 2014; Johnson et al., 2010; Odum, 2011), suggesting some trait-like aspect of delay discounting. The present study found evidence to support this hypothesis in the form of significant positive correlations between money and cigarette discounting rates for smokers in every condition examined. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate the reliability of within-subject, cross-commodity correlations between discounting rates across a range of opportunity costs.

Finally, we assessed whether cigarette smokers would discount delayed money more steeply than would nonsmokers, a finding that is particularly reliable within the discounting literature (e.g., Baker et al., 2003; Bickel, Odum, & Madden, 1999; Heyman & Gibb, 2006; Johnson et al., 2007; Mitchell, 1999; Mitchell & Wilson, 2012; Reynolds, 2006). After controlling for group differences in education, we were unable to demonstrate the predicted effect. Nonsmokers did not differ from Batch 2 smokers in their discounting of delayed money, but nonsmokers discounted delayed money significantly more steeply than Batch 1 smokers. Both findings differ from previous findings that smokers discount money more steeply than do nonsmokers. The molar contingencies governing survey completion (e.g., relation between compensation and work requirement, or unit price for task time) could have influenced the integrity of our sampling. That is, Batch 1 smokers took longer to complete the survey than the nonsmokers despite equivalent pay. Therefore, high-discounting smokers could have exited the survey during this extra task time, leaving a sample of relatively low-discounting smokers. Batch 2 attempted to control for this confound by assessing only money discounting in smokers (i.e., equating unit price for task time with that of nonsmokers), but a discounting difference between this group and nonsmokers was still not obtained.

One possible explanation for the lack of a group discounting difference involves the range of larger–later delays investigated in the present study relative to studies reporting an effect of smoking status. For practical reasons, the longest delay at which discounting was assessed in the present study was 24 hr. By comparison, a delay of 24 hr is equal to or less than the shortest delay assessed in nearly all of the aforementioned studies showing differences in discounting related to smoking status. Given the use of a common delay between the present study and Johnson et al. (2007), we reexamined their indifference point data for $10 and $100 gains at the 24-hr (presented as “1 day”) delay among never smokers, light smokers, and heavy smokers to determine whether an effect of smoking status was evident at this delay and therefore expected in the present study. A mixed model ANOVA with smoking status and magnitude as factors revealed no significant main effects of either factor at the 24-hr delay (both p values ≥ .08). Similarly, no discounting differences as a function of smoking status or magnitude were observed in our Free delay framing condition, the condition most analogous to the typical human delay discounting task used by Johnson et al. (2007). In addition to the consistent lack of statistically significant discounting differences, the overall level of discounting at the 24-hr delay was extremely similar between the two studies: Median indifference points (across both magnitudes) for Johnson et al.’s (2007) never smokers (.98), light smokers (.96), and heavy smokers (.94) were comparable to the present study’s nonsmokers (.97) and Batch 2 smokers (.96). Thus, while the lack of a significant smoking status effect on discounting in the present study seems at first glance at odds with previous research, given that the longest delay was 24 hr in the present study, the lack of difference between smokers and nonsmokers is actually consistent with previous research.

Taken together, our results provide convergent support for Paglieri’s (2013) hypothesis that differences in nonhuman and human discounting performances may be in part driven by procedural differences, specifically the degree of (implicit or explicit) opportunity cost. Overall, results from the Free delay framing condition resembled closely the pattern of minimal discounting observed in typical human delay discounting tasks (i.e., loss of ≤ 10% value at a delay of 1 day), whereas discounting rates from the Return, Browse, and Wait conditions (i.e., conditions involving opportunity costs) resembled those of operant tasks and were higher than rates from the Free condition by orders of magnitude, a distinction consistent with discounting differences observed between nonhuman subjects and human participants. We also found that age and education were significantly and negatively correlated with discounting rates, but almost exclusively in the Free delay framing condition. A related finding was reported by Jimura et al. (2011) in that money discounting rates from a typical human delay discounting task were significantly higher for younger adults compared to older adults, whereas there were no differences between the two groups in the discounting of delayed juice in an operant task. Another difference between delay framing conditions that mirrors the difference between typical human delay discounting task and operant task performances was that money discounting rates from the two extreme conditions, Free and Wait, were not significantly correlated with one another, suggesting two distinct patterns of behavior. This finding is consistent with the results of Johnson (2012), which reported no significant correlations between discounting rates from typical human delay discounting tasks and operant tasks, although rates from tasks of the same type were correlated with one another. Collectively, these outcomes suggest that, across several dimensions, opportunity costs contribute fundamentally to the determination of discounting rates and should therefore be taken into account when comparing between task types within a single species and especially when comparing discounting rates between species.

Several strengths of the present study deserve mention. First, the use of MTurk as a recruitment platform greatly facilitated the rate of data collection while simultaneously minimizing the total cost of the study. MTurk is especially beneficial in this respect when compared to the anticipated time, effort, and financial costs associated with in-person laboratory screening and experimental procedures. Second, although the quality of MTurk data is typically high (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Shapiro, Chandler, & Mueller, 2013), we instituted several tactics to encourage participant attention and engagement such as awarding bonus payments contingent upon systematic delay discounting and embedding distractor questions within the survey. For each of the criteria used to evaluate the quality of discounting data, less than 9% of all sets of indifference points were in violation. This percentage is comparable to laboratory-based delay discounting studies (Beck & Triplett, 2009; Berry, Sweeney, Morath, Odum, & Jordan, 2014; Johnson, 2012; Johnson et al., 2010; Johnson & Bruner, 2012; Lawyer, Williams, Prihodova, Rollins, & Lester, 2010; Mitchell & Wilson, 2010) that have applied similar criteria based on those proposed by Johnson and Bickel (2008). We also conservatively excluded 20% of participants on the basis of failure to correctly answer all distractor questions. Other MTurk researchers have implemented similar strategies based on response accuracy (e.g., Jackson, Weinstein, & Balota, 2013) and completion time (e.g., Bickel et al., 2014; Jarmolowicz et al., 2012. Third, when asked to compare our HIT to others they had completed, MTurk Workers rated the present study as above average (i.e., > 50 [average] on a 0–100 visual analog scale) on the dimensions of ease of completion (M = 65, SD = 29), interest level (M = 61, SD = 28), fairness of compensation (M = 68, SD = 26), and overall experience (M = 65, SD = 23). Despite the comprehensiveness of our discounting assessments, it is encouraging that our survey was viewed favorably by the MTurk community of Workers.

These strengths notwithstanding, there were also limitations of the present study. First, in order to circumvent the practical barriers precluding an evaluation of the effects of opportunity costs on larger–later delays of substantial duration, we asked participants to imagine hypothetical delay framing conditions. Comparable discounting of delayed hypothetical and real rewards is well established (e.g., Baker et al., 2003; Bickel et al., 2009; Johnson & Bickel, 2002; Johnson et al., 2007; Lagorio & Madden, 2005; Madden et al., 2003; Madden et al., 2004; Matusiewicz et al., 2013). However, the question remains for future research whether hypothetical opportunity costs are functionally equivalent to real opportunity costs in this same way. Second, while the use of MTurk conferred numerous advantages, the limited degree of experimental control available to researchers through such an online resource may be undesirable. One example of this limitation in the present study is our inability to confirm the veracity of participants’ self-reported smoking status. In this respect, we acknowledge that there is no ideal substitute for laboratory-based assessments in which smoking status is easily verified biochemically. We also recommend that any alternative (i.e., extralaboratory) medium for research conduct be evaluated in the context of its relative benefits and drawbacks as it pertains to the topic of interest. Not all research agendas are easily integrated into an online framework, while delay discounting and other behavioral economic phenomena are exceptional in this regard. Finally, we attempted to manipulate opportunity costs associated with larger–later reward delays by varying qualitatively one’s access to reinforcement during this period, a method rich in face validity but potentially lacking in quantitative rigor. For this reason, we have purposely avoided formal inclusion of our independent variable as a parameter in Equation 1 as suggested by Paglieri. To do so convincingly would have required us to devise especially contrived hypothetical framing conditions in which opportunity costs were specified explicitly in terms of income foregone per unit time (for a behavioral-ecologic example of this approach, see Wikenheiser, Stephens, & Redish, 2013). Rather, our goal was to differentiate our delay framing conditions descriptively and in a manner that preserved somewhat their realism, an objective that was clearly effective as evidenced by differences in discounting across delay framing conditions.

In conclusion, the present study provides preliminary support for the effects of opportunity costs on the discounting of multiple commodities and reward magnitudes. In that we were able to reproduce several notable features of delay discounting, we also successfully demonstrated the feasibility of conducting sophisticated discounting assessments in an online medium (MTurk). Beyond the context of the present study, recognition of the influence of opportunity costs on valuation of delayed rewards has potential implications for the promotion of health behavior and treatment of reinforcer pathologies (Bickel, Johnson, et al., 2014), for example, differences in alternative reinforcement available in inpatient versus outpatient drug treatment facilities. Before translational efforts such as these can be realized, however, further research based in the laboratory will be required to increasingly specify the impact of this economic variable on choice involving delayed rewards.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA032363 & R21DA032717) awarded to Matthew W. Johnson. Patrick S. Johnson and Evan S. Herrmann were supported by an institutional training grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA007209). The authors wish to thank Mary Sweeney for her insightful comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Patrick S. Johnson, Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Evan S. Herrmann, Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Matthew W. Johnson, Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

References

- Ainslie G. Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:463–496. doi: 10.1037/h0076860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir O, Rand DG, Gal Y. Economic games on the internet: The effect of $1 stakes. PloS One. 2012;7:e31461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axon RN, Bradford WD, Egan BM. The role of individual time preferences in health behaviors among hypertensive adults: A pilot study. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 2009;3:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RC, Triplett MF. Test-retest reliability of a group-administered paper-pencil measure of delay discounting. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:345–355. doi: 10.1037/a0017078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, McGlone MS, Dragojevic M. Bacteria as bullies: Effects of linguistic agency assignment in health message. Journal of Health Communication. 2014;19:340–358. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MS, Sweeney MM, Morath J, Odum AL, Jordan KE. The nature of impulsivity: Visual exposure to natural environments decreases impulsive decision-making in a delay discounting task. PloS One. 2014;9:e97915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Franck CT, Carrin C, Gatchalian KM. Altruism in time: Social temporal discounting differentiates smokers from problem drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;224:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2745-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:641–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Jones BA, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish AD. Single- and cross-commodity discounting among cocaine addicts: The commodity and its temporal location determine discounting rate. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;217:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: Fictive and real money gains and losses. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:8839–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, George Wilson A, Franck CT, Terry Mueller E, Jarmolowicz DP, Koffarnus MN, Fede SJ. Using crowdsourcing to compare temporal, social temporal, and probability discounting among obese and non-obese individuals. Appetite. 2014;75:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford WD. The association between individual time preferences and health maintenance habits. Medical Decision Making. 2010;30:99–112. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09342276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon's Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ, Mach JL, Newman JL, Perry JL. Delay discounting as a predictor of drug abuse. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RR, DiFeo A, Bogie K, Zhang GQ, Sun J. Crowdsourcing awareness: Exploration of the ovarian cancer knowledge gap through Amazon Mechanical Turk. PloS One. 2014;9:e85508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SR, Fantino E. Commodity specific rates of temporal discounting: Does metabolic function underlie differences in rates of discounting? Behavioural Processes. 2008;77:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, White L, Kowalewski T, Aggarwal R, Lintott C, Comstock B, Lendvay T. Crowd-sourced assessment of technical skills: A novel method to evaluate surgical performance. Journal of Surgical Research. 2014;187:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump MJ, McDonnell JV, Gureckis TM. Evaluating Amazon's Mechanical Turk as a tool for experimental behavioral research. PloS One. 2013;8:e57410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty JR, Brase GL. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Flory JD, Acheson A, McCloskey M, Manuck SB. IQ and nonplanning impulsivity are independently associated with delay discounting in middle-aged adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Diergaarde L, Pattij T, Poortvliet I, Hogenboom F, de Vries W, Schoffelmeer AN, De Vries TJ. Impulsive choice and impulsive action predict vulnerability to distinct stages of nicotine seeking in rats. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Marley J, Jacobs EA. Delay discounting by pathological gamblers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Jankowiak N, Lin H, Paluch R, Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. No food for thought: Moderating effects of delay discounting and future time perspective on the relation between income and food insecurity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.079772. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel JE, DeHart WB, Madden GJ, Odum AL. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Discounting of monetary and consumable outcomes in current and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3597-z. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RM, Brown DL, Boice R. Using Amazon's Mechanical Turk website to measure accuracy of body size estimation and body dissatisfaction. Body Image. 2012;9:532–534. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty E, Karpel H, Silberberg A. Time preferences in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) and humans (Homo sapiens) Animal Cognition. 2012;15:1161–1172. doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Fry AF, Myerson J. Discounting of delayed rewards: A life-span comparison. Psychological Science. 1994;5:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Lichtman D, Rosen S, Fry A. Temporal discounting in choice between delayed rewards: The role of age and income. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:79–84. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao T, Rusanov A, Boland MR, Weng C. Clustering clinical trials with similar eligibility criteria features. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.01.009. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Peters EN, Boden MT, Bonn-Miller MO. A comprehensive examination of delay discounting in a clinical sample of Cannabis-dependent military veterans making a self-guided quit attempt. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21:55–65. doi: 10.1037/a0031192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GM, Gibb SP. Delay discounting in college cigarette chippers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17:669–679. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280116cfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Hackenberg TD. Token reinforcement, choice, and self-control in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;66:29–49. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.66-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JD, Weinstein Y, Balota DA. Can mind-wandering be timeless? Atemporal focus and aging in mind-wandering paradigms. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:742. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Bickel WK, Carter AE, Franck CT, Mueller ET. Using crowdsourcing to examine relations between delay and probability discounting. Behavioural Processes. 2012;91:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroni JL, Wright SM, Lerman C, Epstein LH. Relationship between education and delay discounting in smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1171–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimura K, Myerson J, Hilgard J, Braver TS, Green L. Are people really more patient than other animals? Evidence from human discounting of real liquid rewards. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:1071–1075. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.6.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]