Abstract

Chilling rapidly (<4 h) clusters Glycoprotein - (GP)Ib receptors on blood platelets, and ß2-integrins of hepatic macrophages bind ßGlcNAc residues in the clusters leading to rapid clearance of acutely chilled platelets following transfusion. Although capping the ßGlcNAc moieties by galactosylation prevents clearance, this strategy is ineffective after prolonged (>24 h) refrigeration. We report here that prolonged refrigeration increases the density/concentration of exposed galactose residues such that hepatocytes become increasingly involved in the removal of platelets using their Ashwell-Morell receptors. Macrophages always rapidly remove a large fraction of transfused platelets (~40%). With platelet cooling, hepatocyte-dependent clearance further diminishes their recoveries following transfusion.

INTRODUCTION

Platelets, unlike other transplantable tissues or cell types, do not tolerate refrigeration and disappear rapidly from the circulation if subjected to prior chilling 1-3. Platelets for transfusion are therefore stored at room temperature. Since platelet transfusions were routinely implemented in clinical practice in the 1950s, improvements in platelet collection and handling techniques have greatly increased the quality and safety of platelet products. However, the risk of bacterial infection transmitted through such platelet concentrate transfusion is estimated to be 50 times higher than for transfusion of refrigerated red blood cell products 4,5. Bacterial sepsis is currently considered the major risk factor for transfusion-transmitted disease. Thus, regulatory agencies limit blood storage to 5 days and this short shelf life severely compromises platelet inventories and creates chronic shortages 6,7. Cold storage of red blood cell units suppresses bacterial contamination. Presumably, platelet refrigeration would also minimize the risk of transfusion-mediated bacteremia, permitting extended storage time and reducing the number of outdated products. However, cold storage per se does not prevent bacterial or viral contamination of donated blood. A combination of pathogen inactivation technology however, could reduce bacterial and viral growth 8, eliminating severely compromised platelet inventories and chronic platelet shortages.

We recently defined that β2 integrins on hepatic resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) selectively recognize irreversibly clustered glycans (β-N-acetylglucosamine (βGlcNAc)-terminating immature glycans) on GPIb receptors on < 4 h short-term cooled (0 °C) platelets, leading to their rapid clearance from the circulation 2. Capping surface βGlcNAc residues by enzymatic galactosylation with endogenous enzymes prevents short-term cooled murine platelet clearance and inhibits the ingestion of chilled human platelets by human macrophage-like cells (THP-1 cells) in vitro 9, providing a simple method to accommodate human chilled platelet survival. For logistical reasons, we used in our early studies isolated platelets and had not stored mouse platelets for clearance studies longer than hours. In contrast, platelets for transfusion are stored for days as platelet rich plasma. Therefore, the clinical trial has been performed using apheresis platelets refrigerated for 48 h. This phase I clinical trial administering autologous, radiolabeled galactosylated apheresis platelets refrigerated for 48 h into human volunteers clearly showed that the galactosylation procedure did not extend their circulation time 10. Subsequently we found that just as with human platelets stored in plasma, galactosylation has no effect on the survival of > 48 h long-term cooled mouse platelets 10. The use of 48 h of cold storage was based on a study showing that prolonged refrigeration (> 12 h) is necessary to induce accelerated clearance of platelets refrigerated in plasma 3. In addition, temperature induced changes, such as microtubular disassembly, become irreversible with > 24 h of cooling 11,12.

Using the murine transfusion model, we have dissected the clearance mechanism for platelets refrigerated for > 48 h. We have found that as with short-term cooling, platelets refrigerated for 48 h (designated throughout the manuscript as long-term refrigerated platelets or 4 °C platelets) are removed from the recipients’ circulation by the liver 13 but, unexpectedly, by the hepatocyte Ashwell-Morell asialoglycoprotein receptor (Asgr1/2). Prolonged refrigeration increases the density/concentration of exposed βgalactose (βGal) residues on platelet glycoproteins, specifically on GPIbα and its major ligand von Willebrand factor (vWf), such that hepatocytes effect clearance mediated by their Asgr1/2 receptors. These findings again link glycan exposure with a lectin-mediated platelet clearance mechanism.

RESULTS

Clearance of refrigerated platelets is mediated by hepatocytes

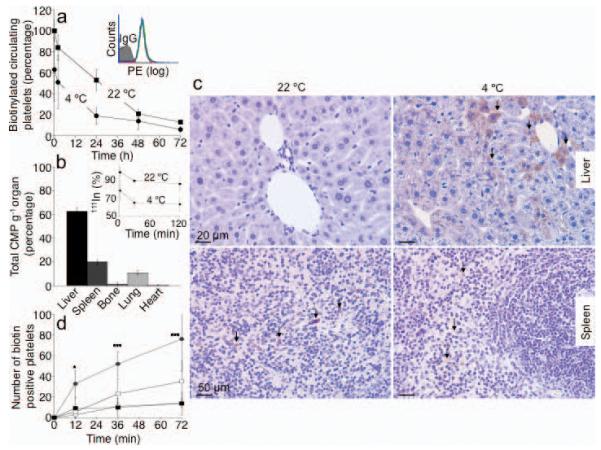

Murine platelets refrigerated in plasma for 48 h and injected into wild type (WT) mice are cleared rapidly from the circulation independent of αMβ2 receptors on macrophages 10, indicating the presence of other clearance mechanisms. Approximately 50% of biotinylated long-term (4 °C) refrigerated (Fig. 1a) or 111Indium-labeled (Fig. 1b, Inset) platelets were cleared within 2 h following platelet infusion, as previously demonstrated for fluorescently-labeled platelets 10. The diminished recoveries and survivals of long-term refrigerated biotinylated platelets do not reflect a loss of platelet labeling as platelet biotinylation was stable at 4 °C for at least 48 h (Fig. 1a, Inset). As expected, fresh room temperature (22 °C) biotinylated (Fig. 1a) or 111Indium-labeled (not shown) platelets are cleared at a constant rate, with a half-life less than 24 h. Survivals of biotinylated fresh (22 °C) platelets or biotinylated platelets stored for 48 h at 4 °C were 72.34 ± 5.4 h and 59.48 ± 3.9 h, respectively; recoveries of fresh or 48 h (4 °C) stored biotinylated platelets were 78.0 ± 12 h and 60.2 ± 9.25 h, respectively.

Figure 1.

Hepatocytes clear long-term refrigerated platelets. (a) Comparison of fresh (22 °C) or 48 h refrigerated (4 °C) biotinylated platelet survival in wild type (WT) mice. Data are from 5 mice for each condition. Insert. Platelet biotinylation is stable: fresh (red line); 24 h (green line) or 48 h (blue line) refrigerated platelet histograms. (b) 111Indium-labeled refrigerated platelets were injected into WT mice and tissues were harvested after 30 min. The survival of 111Indium-labeled platelets is also shown (Inset). Data are expressed as percent of total radioactivity CPM g−1 tissue. Each bar depicts the mean values for 4 animals ± s.e.m. (c) Biotinylated fresh (22 °C, left panel) or 48 h refrigerated (4° C, right panel) platelets were injected into WT mice. Livers (upper panels) and spleens (lower panels) were harvested 5 min after platelet transfusion and the distribution of platelet-derived biotin determined. Abundant biotin (arrows) is detected in hepatocytes when 4 °C, but not when fresh, 22 °C platelets were transfused. Images are representative of 10 randomly selected fields in organs harvested from 3 different mice. (d) Biotin-positive hepatocytes or macrophages were quantified in sections of organs harvested 5, 15 and 30 min after platelet transfusion (* P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Spleen 22 °C (□) and 4 °C (■); Liver 22 °C (○) and 4 °C (●). Data from 3 mice at each time point ± s.e.m.

We next investigated the tissue fate of these long-term refrigerated platelets transfused into recipient mice. The major destination of 111Indium labeled long-term refrigerated platelets is the liver (Fig. 1b), followed by the spleen and lungs, whereas fresh room temperature platelets are removed equally in both the spleen and liver 2,14. Surprisingly, 5 min after transfusion, biotinylated long-term refrigerated platelets associate with hepatocytes (Fig. 1c, upper right panel) and not with liver resident macrophages, as shown earlier for short-term cooled platelets2. Biotin-labeling intensities vary between hepatocytes (Fig. 1c), most likely reflecting the platelet accessibility to the hepatocyte apical surface as blood flows through the hepatic sinusoids resulting in differential binding and uptake of platelets by hepatocytes. Biotinylated long-term refrigerated platelets are found in hepatocytes as early as 5 min following transfusion (Fig. 1c and d). Quantification of platelet ingestion in liver sections revealed 4-6-fold more hepatocytes (P < 0.001) containing biotin in livers isolated 30 min after infusion of long-term refrigerated platelets compared to those from animals injected with fresh platelets (22 °C) (Fig. 1d). Few transfused biotinylated freshly isolated platelets were found in recipient livers at these time points (Fig. 1c, upper left panel and Fig. 1d). In spleen, biotin staining was associated only with the macrophage-containing red pulp following the infusion of either fresh isolated or cold-stored platelets (Fig. 1c, lower panels). A slightly higher (2-fold) amount of biotin-positive cells was found in spleens removed from mice 30 min after transfusion with fresh platelets (Fig. 1d).

HepG2 cells ingest long-term refrigerated human platelets in vitro

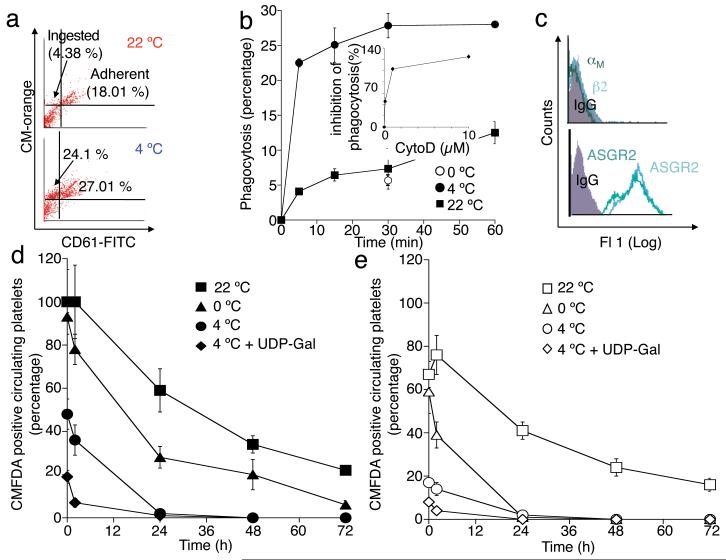

The surprising finding that hepatocytes contain transfused platelets in situ led us to investigate if cultured hepatocyte cell lines (HepG2 cells) are also capable of ingesting human platelets in vitro. Isolated and labeled platelets were added to cultures of HepG2 cells and the degree of binding and ingestion determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 2a). Human platelets avidly bind to the surface of HepG2 cells and are internalized (Fig. 2b). Platelet binding to HepG2 cells was enhanced by ~10% by cold storage (Fig. 2a). However, human platelet ingestion by HepG2 cells is ~4 fold increased by cold storage (Fig. 2b). Since HepG2 cells do not express αMβ2-receptors (Fig. 2c), which we reported previously as being able to recognize short-term cooled platelets, it is therefore not surprising that short-term cooling did not enhance platelet uptake by HepG2 cells (Fig. 2b). Platelet ingestion by hepatocytes was inhibited by cytochalasin D showing that it requires mobilization of the hepatocyte actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 2b, Inset). The in vitro results therefore confirm our in situ finding that hepatocytes can ingest long-term refrigerated platelets.

Figure 2.

HepG2 cells ingest long-term refrigerated human platelets in vitro. (a) Ingestion of CM-Orange-labeled platelets is detected by flow cytometry as an increase in hepatocyte associated orange fluorescence (CM-Orange, y-axis). (b) Ingestion of fresh (22 °C), short-term (0 °C) or long-term refrigerated platelets (4 °C) by HepG2 cells. Long-term refrigeration increases the number of hepatocytes ingesting platelets by 4-5 fold. The inset shows a dose dependent inhibition by cytochalasin D of platelet uptake by HepG2 cells. Values are compared to room temperature platelet uptake. Mean ± s.e.m. of 3 experiments is shown. (c) HepG2 cells express both the ASGR1 and ASGR2 subunits of the Ashwell-Morell receptor but do not express αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18) receptors. Representative flow cytometry histograms are shown. (d, e) Long-term refrigerated platelets are cleared predominantly by macrophage independent mechanisms. Survival of fresh room temperature (22 °C), short-term cooled (0 °C), long-term refrigerated (4 °C) or galactosylated long-term refrigerated (4 °C + UDP-Gal) platelets injected into recipient macrophages depleted (d) mice or in mock treated mice (e) are shown. The percentage of fresh platelets at 5 min in WT mice depleted of macrophages was set at 100%. Each time point is the mean of data from seven mice ± s.e.m.

Contribution of macrophages to refrigerated platelet clearance

To assess the relative roles of hepatocytes and macrophages in platelet clearance, we purged recipient mice of mature hepatic and splenic macrophages by injecting toxic clodronate-encapsulated liposomes prior to transfusions of fresh or short- or long-term refrigerated and/or galactosylated platelets 15,16. Platelet recoveries and survivals were determined in these animals and compared to mock-treated recipients (Table 1). The 5 min recoveries of fresh platelets injected into macrophage-depleted mice (119.0 ± 6.35) were set to 100% and the data (Fig. 2d and e) are presented relative to this value. Macrophage depletion enhances the recovery of fresh platelets by 30-40% but has little effect on their survival times (Fig. 2d and e, and Table 1). Diminished platelet recovery in normal mice may reflect the detection of damage inflicted during isolation and is consistently observed following the transfusion of fresh platelets into healthy volunteers 10. As expected, macrophage depletion significantly increases both the recovery and survival times (P < 0.05) of platelets stored short-term at 0 °C (Table 1), although the recovery of short-term cooled platelets is not fully restored, indicating that other cells, i.e., hepatocytes, initially also remove transfused platelets. The difference in short-term cooled platelet survival in mice depleted of macrophages and in control mice is particularly apparent following 24 h after platelet transfusion (Fig. 2), showing that short-term refrigerated platelets circulate significantly better in macrophage-depleted mice than in control mice. However, even in macrophage-depleted mice, short-term cooled platelet survival (~63 h) is slightly shorter when compared to fresh platelet survival (~78 h), indicating that other cells, i.e. hepatocytes, already participate in the clearance of short-term cooled platelets (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Recovery and survival of mouse platelets transfused into mice of indicated genotype, or transfused into control-liposome or clodronate-liposome treated mice. Recoveries and survival of O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase (OSP) treated or untreated mouse platelets transfused into WT mice are also shown. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

| Survival (h) | Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Platelets transfused into Asgr1−/− mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C | 91.57 ± 2.24** | 90.5 ± 3.56 |

| 4 °C | 71.90 ± 2.12*** | 75.24 ± 1.63 |

|

| ||

| Platelets transfused into Asgr2−/− mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C | 94.14 ± 1.59*** | 105.40 ± 2.96 |

| 4 °C | 72.81 ± 1.29*** | 75.77 ± 1.04 |

|

| ||

| Platelets transfused into WT mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C | 80.29 ± 2.02 | 76.83 ± 1.59 |

| 4 °C | 56.12 ± 2.23 | 40.57 ± 2.14 |

|

| ||

| Platelets transfused into PBS-liposome treated mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C | 75.03 ± 1.61 | 74.12 ± 4.25 |

| 0 °C | 48.33 ± 0.75 | 64.42 ± 2.60 |

| 4 °C, UDP-Glucose | 46.354 ± 0.99** | 50.92 ± 3.21 |

| 4 °C, UDP-Galactose | 54.69 ± 3.07 | 37.08 ± 5.20 |

|

| ||

| Platelets transfused into clodronate-liposome treated mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C | 78.53 ± 2.23 | 119.0 ± 6.35 |

| 0 °C | 63.41±3.47* | 96.05 ± 1.45 |

| 4 °C, UDP-Glucose | 49.47 ± 1.91 | 61.36 ± 5.44 |

| 4 °C, UDP-Galactose | 55.89 ± 2.76 | 48.42 ± 2.36 |

|

| ||

| Platelets transfused into control-liposome mice | ||

|

| ||

| 22 °C, untreated | 79.51± 4.497 | 74.52 ± 10.38 |

| 22 °C, OSP-treated | 83.58± 5.67 | 77.15 ± 7.19 |

| 4 °C, untreated | 56.49± 0.82 | 45.44 ± 6.44 |

| 4 °C, OSP-treated | 61.08± 1.75* | 67.37 ± 5.01* |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001.

As reported, recoveries of long-term refrigerated platelets are lower compared to fresh platelet recoveries in mice containing macrophages (Fig. 2e) 10. Macrophage depletion shows that only a very small portion (~10-20%) of the initial long-term refrigerated platelet removal is dependent on macrophage αMβ2 receptors (Fig 2d and e). Galactosylation covers exposed βGlcNAc residues and deprives macrophage αMβ2 receptors of this platelet ligand 9. However, the addition of galactose would be expected to promote clearance by galactose recognizing lectins. Consistent with this notion, galactosylation of long-term refrigerated platelets significantly decreased (~10-20%) their recovery (P < 0.01, not shown) in macrophage-depleted mice, showing that depriving the αMβ2 macrophage receptor of its ligand promotes clearance by galactose-recognizing lectins, pointing to the dual roles of lectin receptors in chilled platelet clearance in the liver. Therefore, the αMβ2 macrophage receptor contributes in part to the initial removal of long-term refrigerated platelets but does not determine their ultimate survival. Consistent with this result, the initial recoveries of galactosylated long-term refrigerated platelets in untreated mice are reduced by ~15% (P < 0.001, not shown) compared to non-galactosylated long-term refrigerated platelets (Fig. 2e), as shown before 10.

These findings confirm our early studies showing that after an initial and rapid macrophage-dependent removal of ~ 40% of transfused platelets independent of storage conditions, the remaining short-term refrigerated platelets in the circulation are predominantly cleared by macrophages (Kupffer cells). In contrast after prolonged refrigeration, hepatocytes become the main removal site of circulating platelets. With prolonged platelet refrigeration, hepatocyte-dependent removal mechanisms increase the rate of platelet clearance.

The Ashwell-Morell receptor in refrigerated platelet clearance

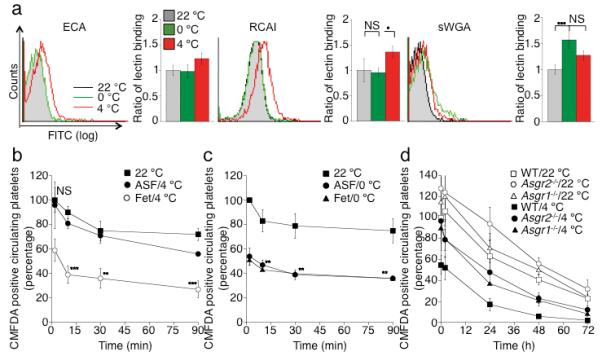

We previously reported that short-term cooled platelets have exposed/clustered βGlcNAc residues that are recognized and phagocytozed by the αMβ2 hepatic macrophage receptors 9,17. In contrast, platelets refrigerated for long periods have increased galactose exposure as evidenced by the galactose-binding lectins, RCA I and ECA (Fig. 3a), suggesting that galactose-recognizing asialoglycoprotein receptors may be involved in their clearance. We, therefore, investigated if long-term refrigerated platelet clearance is mediated by Ashwell-Morell receptors on hepatocytes. Co-injections of long-term refrigerated platelets and the Ashwell-Morell receptor competitor asialofetuin into wild type mice dramatically improved recoveries and circulation of long-term refrigerated (4 °C) platelets compared to fresh room temperature (22 °C) platelet recoveries (Fig. 3b). In contrast, recoveries and survivals of short-term refrigerated platelets are not affected by asialofetuin co-injections (Fig. 3c). These results indicate that the Ashwell-Morell receptor mediates the initial removal of circulating long-term, but not short-term refrigerated platelets in vivo. We next evaluated the survival of long-term refrigerated platelets in mice lacking either the Asgr1 or Asgr2 chains of the Ashwell-Morell receptor. Long-term refrigerated platelets, transfused into mice lacking Asgr1 or 2, had similar recoveries as fresh platelets and their survival times were almost normalized in Asgr1 and 2 deficient animals (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001 for Asgr1−/−; Asgr2−/−, respectively) (Fig. 3d and Table 1). Therefore, the removal of long-term refrigerated platelets is mediated by Ashwell-Morell receptors on hepatocytes. The recovery and survival of fresh platelets were also significantly enhanced in Asgr1 or Asgr2 deficient mice (Fig. 3d and Table 1) revealing that the hepatocyte Ashwell-Morell receptors routinely survey the platelet surface for galactose exposure 18.

Figure 3.

The Ashwell-Morell receptor mediates the hepatic recognition and clearance of long-term refrigerated platelets. (a) βGalactose exposure on glycoproteins is detected with RCA I and ECA lectins. Lectin binding to fresh (22 °C), short-term cooled (0 °C) or long-term refrigerated (4 °C) platelets are compared. Exposure of βGlcNAc residues on platelet glycoprotein is detected with the sWGA lectin. The mean fluorescence detected on fresh platelets (22 °C) is defined as 1. Histograms report the mean ± s.e.m. for 3 separate experiments. (b) Long-term refrigerated platelets were co-injected with asialofetuin (ASF/4 °C), a competitive binding inhibitor of the Ashwell-Morell receptor, or fetuin as control (Fet/4 °C) (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Fresh control platelets were also transfused (22 °C). Data are compared to platelet recoveries and survivals of fresh platelets. (c) Short-term cooled platelets were co-injected with asialofetuin (ASF/0 °C), or fetuin (Fet/0 °C) (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Fresh platelets were transfused as a control (22 °C). Data are compared to platelet recoveries and survivals of fresh platelets. (d) Survival of transfused long-term refrigerated (4 °C) or fresh platelets (22 °C) in mice of indicated genotypes. Data on 22 °C platelet clearance: mean of 6 mice ± s.e.m.; Data on 4 °C platelet clearance: mean of 3-5 mice ± s.e.m.

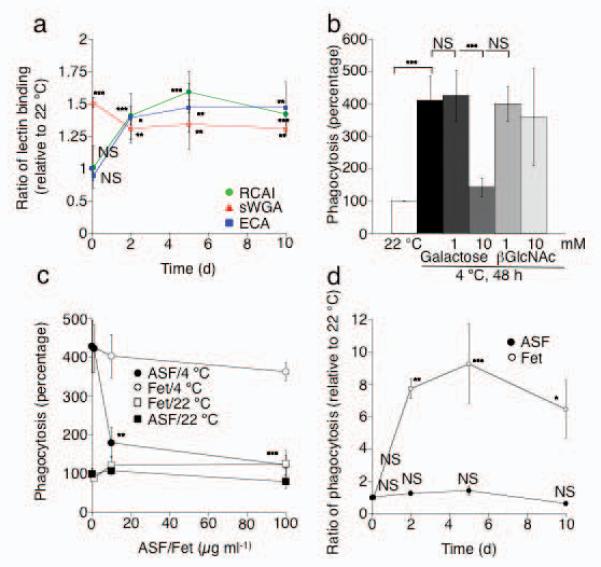

HepG2 cells express both chains (ASGR1 and ASGR2) of the Ashwel-Morell receptor but do not express αMβ2 (CD18/CD11b) receptors (Fig. 2c). As shown for murine platelets, human platelets refrigerated for > 2 h up to 10 d have significantly increased galactose exposure, as measured by RCA I and ECA lectin binding. βGal exposure peaks after 5 d of refrigeration (Fig. 4a). In contrast, elevated βGlcNAc exposure is observed after 2 hours (p < 0.001) of refrigeration, as measured by sWGA lectin binding (Fig. 4a). We observe a slight decrease of sWGA binding after 48 h of refrigeration (Fig. 4a), similar to that found for murine platelets (Fig. 3a). To address the role of galactose exposure in platelet uptake in vitro, we tested if soluble sugars (Galactose or βGlcNAc) inhibit the uptake of long-term refrigerated platelets by HepG2 cells.

Figure 4.

Asialoglycoproteins on long-term refrigerated human platelets are targets for the Ashwell-Morell receptor on HepG2 cells. (a) Platelet concentrates were stored at 4 °C for up to 10 d. βGal or βGlcNAc exposure on human platelets was measured using RCA I and ECA lectin or sWGA lectin, respectively. MFI values for each lectin measured at 22 °C were set as 1. Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of 4 independent experiments. NS > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All values are compared to lectin binding values to 22 °C platelets. (b) Effect of soluble galactose, or βGlcNAc, on the ingestion of long-term refrigerated platelets (4 °C) by HepG2 cells. All values are compared to HepG2 cells incubated with 22 °C platelets. (c) Asialofetuin (ASF), but not fetuin (Fet), inhibits the ingestion of long-term refrigerated platelets by HepG2 cells. ASF or fetuin was added to HepG2 cells and platelets at the indicated concentrations. Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of 3 independent experiments. All values are compared to HepG2 cells incubated with 22 °C platelets. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (d) Effect of Asialofetuin (100 μg ml−1, ASF) or fetuin (100 μgml−1, Fet) on the ingestion of human platelets refrigerated for up to 10 days by HepG2 cells. All values are compared to HepG2 cells incubated with fresh RT and 100 μg ml−1 fetuin. NS > 0.05 *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The uptake of long-term refrigerated platelets is significantly (P < 0.01) inhibited by 10 mM of galactose whereas βGlcNAc was without effect (Fig. 4b). Asialofetuin, but not fetuin, also significantly inhibited long-term platelet uptake in a dose dependent manner (P < 0.05 and 0.001 for 10 and 100 μg ml−1 asialofetuin, respectively) (Fig. 4c), consistent with its effect on the survival of platelets in mice transfused with long-term refrigerated murine platelets (Fig. 3b). We next tested if human platelets refrigerated for longer periods (≤10 d) are taken up by HepG2 cells in similar fashion to 48 h refrigerated platelets. Platelets cooled for 2 h at 0°C are not ingested by HepG2 cells, whereas prolonged refrigeration leads to a significant increase of platelet uptake by HepG2 cells at d 2, 5 and 10 (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4d). Maximal platelet ingestion is observed after 5 d of refrigeration, which correlates with the increased βGal exposure measured at d 5 (Fig. 4a). Ingestion of long-term refrigerated platelets is significantly inhibited by the addition of asialofetuin (100 μg ml−1). These findings point to exposed galactose residues and the Ashwell-Morell receptors in the HepG2-mediated human platelet uptake in vitro.

Platelet GPIbα is a counter receptor for Ashwell-Morell receptors

We investigated if GPIbα, a component of the GPIb-IX-V receptor complex that binds von Willebrand factor plays a role in the removal of long-term refrigerated platelets, as we previously reported for short-term cooled platelets. The extracellular domain of GPIbα contains 60% of total platelet glycan content in the form of N- and O-linked glycan chains 19-21. Two of the putative N-linked glycans are localized within the 45 kDa of GPIbα extracellular domain 22. We stripped the 45 kDa domain of the extracellular GPIbα domain from human and mouse platelets with mocarhagin or O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase, respectively 2, and determined whether its loss affected platelet uptake by HepG2 cells in vitro or platelet survival in recipient mice in vivo. Removal of the extracellular domain of GPIbα before platelet storage prevents human platelet ingestion by HepG2 cells in vitro (P < 0.001) and significantly improves the recovery and survival of long-term refrigerated platelets (P < 0.05) injected into wild type mice (Fig. 5a and b and Table 1) (P < 0.05). These findings, therefore, implicate recognition of GPIbα glycans by the Ashwell-Morell receptor as a critical event in the initiation of platelet clearance.

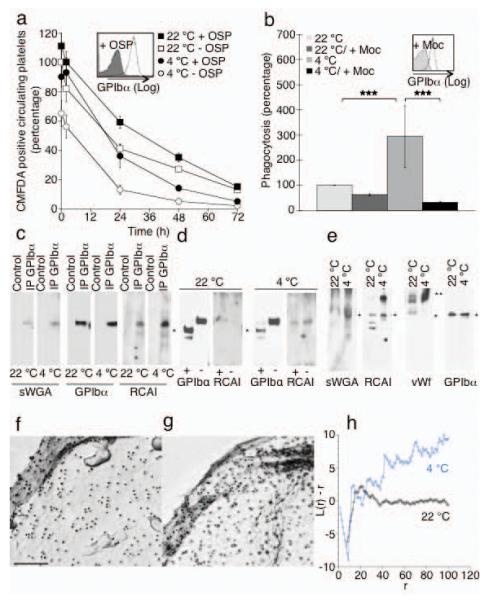

Figure 5.

The extracellular domain of GPIbα is required for recognition of platelets by the Ashwell receptor. (a) Survivals of fresh (22 °C) or long-term refrigerated mouse platelets (4 °C) stripped of GPIbα 45 kDa domain by enzymatic treatment with O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase (+ OSP). Mean ± s.e.m. for 5-6 recipient mice. Inset. Flow cytometric analysis of GPIbα on untreated (− OSP) and treated (+ OSP) platelets. (b) Effect of the GPIbα N-Terminus removal by mocarhagin (Moc, inset) on the ingestion of fresh (22 °C) or long-term refrigerated human platelets (4 °C) by HepG2 cells. ***P < 0.001 (c) GPIbα immunoprecipitates (IP GPIbα) from fresh (22 °C) or long-term refrigerated mouse platelets (4 °C) were subjected to immunoblotting using RCA I or sWGA lectins. n = 3. (d) GPIbα immunoprecipitates from control platelets (−) or following treatment with OSP (+) were subjected to immunoblotting using anti GPIbα antibodies or RCA I lectin. GPIbα’s C-Terminus is indicated (*). (e) Immunoblotts of total platelet lysates from fresh (22 °C) or long-term refrigerated platelets (4 °C) using sWGA, RCA I lectins or antibodies to mouse vWf or GPIbα. GPIbα (*) and VWf (**) are indicated. n = 3. (f-h) GPIbα aggregates on human cold stored platelets. GPIbα is visualized by electron microscopy. Surface of a (f) fresh platelet (22 °C) and a (g) long-term refrigerated platelet (4 °C). (h) Quantification of gold aggregate size in control and stored platelets. A plot of L(r) - r vs. r visualizes clustering. Values <-1 indicate dispersal whereas values >1 indicate significant clustering.

We next demonstrated that exposed βGlcNAc or βGal residues that mediate the recognition by the αMβ2 lectin domain, or the Ashwell-Morell receptor, reside on GPIbα, respectively. Binding of peroxidase-labeled sWGA 9 or RCA I to GPIbα is readily detectable in displays of total platelet proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5e), demonstrating that GPIbα contains the bulk of glycans with exposed βGal residues present on platelets. Binding of sWGA and RCA I to GPIbα is also detectable in GPIbα immunoprecipitates from fresh mouse platelets (Fig. 5c). However, following prolonged platelet refrigeration and rewarming, lectin binding to βGlcNAc and βGal residues on the GPIbα polypeptide is markedly increased (Fig. 5c). No binding of RCA I to the C-terminal region of GPIbα was observed following treatment of platelets with O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase (Fig. 5d), showing that the bulk of RCA I reactive βGal resides within GPIbα’s N-terminus. A small portion of GPIbα, recognized by peroxidase-conjugated RCA I, remains intact after O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase treatment, possibly because it is sequestered in the open canalicular system (Fig. 5d). Immunoblots of lysates from fresh platelets with peroxidase-labeled RCA I contain multiple stained bands: one corresponding to GPIbα; two polypeptides of lower molecular weights (Fig. 5e); and a large polypeptide of ~260 kDa. RCA I lectin binding to the ~260 kDa polypeptide is markedly increased after long-term refrigeration. This platelet-associated protein of 260 kDa has the similar molecular mass as vWf as shown by immnoblotting using an antibody to mouse vWf (Fig. 5e).

In accordance with this finding we detect increased vWf binding to the surface of long-term refrigerated human and murine platelets by flow cytometry. Refrigeration of human platelets for 48 h in plasma increased binding of vWf by 6-fold (4.5% ± 0.77 for RT, 31% ± 1.99 for 48 h, 4 °C, P < 0.05). Similarly, long-term refrigeration of murine platelets in plasma resulted in enhanced binding of vWf (1.1% ± 0.1 for RT to 9.5% ± 0.2 for 48 h, 4 °C, P < 0.01). Normally, GPIbα is arranged in linear arrays on the surface of fresh resting platelets 23 but aggregates following short term refrigeration3. Prolonged cooling promotes clustering of GPIbα on the surface of the long-term stored cells (Fig. 5 f-h).

DISCUSSION

We have made the surprising observation that the removal of platelets stored long-term by refrigeration that escape a careful initial macrophage surveillance system is mediated primarily by the Ashwell-Morell asialoglycoprotein receptor (Asgr1/2) on hepatocytes. This conclusion is based on the following evidence: (1) macrophage depletion in mice using clodronate encapsulated liposomes, a procedure that significantly improves the circulation of 2h chilled and transfused platelets, does not prevent the clearance of 48h chilled platelets; (2) streptavidin-POD staining reveals abundant long-term refrigerated and biotinylated platelets in hepatocytes; (3) 48 h-refrigeration increases by ~1.5-fold the binding of the βgalactose-recognizing lectin RCA; (4) KO mice lacking Asgr-1 or Asgr-2 subunits of the Asgr1/2 support 48 h-refrigerated platelet circulation times comparable to room temperature stored platelets; (5) Co-injection of asialofetuin, a competitive inhibitor of asialoglycoprotein-receptors, restores the survival of 48 h-refrigerated platelets in WT mice; and (6) hepatocyte HepG2 cells ingest fluorescently labeled long-term refrigerated platelets in culture, and asialofetuin prevents this ingestion. Regarding the platelet target of the Asgr-1/Asgr-2 receptors, circulation of 48 h-refrigerated platelets is markedly improved by removal of GPIbα’s N-Terminal domain using O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase by hepatocyte Ashwell-Morell receptors.

Our studies, combined with the recent report by Grewal et al, point out the importance of a hepatic-based platelet removal system that uses its Asgr1/2 to recognize defectively sialylated proteins and remove platelets expressing desialylated glycans on their surface 18. The idea that hepatocytes might ingest larger material has been controversial 24. Whether hepatocytes also remove senile platelets remains to be established. Platelet lifespan is ultimately limited by endogenous platelet apoptotic machinery 28. Although macrophages are widely regarded as the key phagocytes in platelet removal 25-27 we have found that refrigerated and fresh room temperature platelets are cleared in their absence. Although macrophages do not play a substantial role in determining platelet survival, they regulate platelet recoveries following transfusion (Table 1).

Platelets from ST3GalIV−/− mice have exposed galactose on surface glycoproteins because they lack α2-3-sialyltransferase activity 18,29. In long-term refrigerated and rewarmed platelets, the mechanism of galactose exposure remains to be determined. Release, or activation, of sialidase activity during storage could cleave terminal sialic acid residues, revealing underlying galactose residues. Evidence that supports this mechanism is the increased binding of galactose recognizing lectins to platelets. Glycans associated with GPIbα are the major target of this activity. However, the extent of galactose exposure on refrigerated platelets is less than that present on the surface of ST3GalIV+/− platelets that retain their ability to circulate with normal lifetimes 18,29. Hence, other changes in the platelet with cooling might amplify the galactose signal. For example, clustering of GPIbα subunits, facilitated by cytoskeletal and membrane phase changes 30,31, could increase the localized density of galactose or glycan presentation, enhancing lectin avidity and binding. Changes in lipid structure could facilitate protein clustering, and facilitate alterations in lipid-glycan density and/or presentation 32,33. However, the functional relationship between GPIbα clustering and platelet clearance by hepatocyte Ashwell-Morell remains to be established, particularly, if proteolytic removal of GPIbα’s N-Terminal 45 kDa portion alters clustering.

How does GPIbα presentation influence platelet clearance? Although platelets stripped of the extracellular domain of GPIbα do not circulate when transfused 34, removal of the N-terminal extracellular 45 kDa vWf binding domain of GPIbα from long-term refrigerated platelets restores survival (Fig. 5a), and prolongs the survival of fresh platelets (Fig. 5a) 3. GPIbα’s N-terminal domain contains di-, tri-, and tetra-antennary N-linked glycans 35,36 whereas O-linked glycans reside within the C-terminal domain 21,37. Removal of the N-terminal 282 residues of GPIbα from human platelets using the snake venom protease mocarhagin 38 or O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase eliminates two putative N-glycan residues, as well as the vWf-binding region of GPIbα 38. It is tempting to speculate that most of the exposed βGal residues reside within N-linked glycans on GPIbα, as shown previously for βGlcNAc 10 and that these changes mediate the recognition and removal of platelets, consistent with the shown effects of ligand valency (tetra-, > tri-, > di-, > mono-antennary) and sugar spacing (20 Å > 10 Å > 4 Å) on glycan binding to hepatic Asgrs 24.

Removal of the 45 kDa domain does not, however, completely rescue the initial recovery of long-term refrigerated platelets (Fig. 5), indicating that other factors influence the initial recovery. Cleavage of the GPIbα by ADAM 17 causes a dramatic loss of platelet recovery following transfusion 39. Loss of GPIbα following refrigeration and rewarming could modulate the recoveries of long-term refrigerated platelets. Exposure of galactose residues on other highly glycosylated receptors such as αIIbβ3, or on platelet bound vWf, could also be effectors, since sialic acid deficient vWf is cleared by Asgr1/2 receptors 18,29 and cooling increases the association of vWf with platelets (Fig. 5d). Proteolytic removal of the GPIbα N-terminal region deprives GPIbα of its vWf-binding domain and bound vWf. Whether vWf-glycans contribute to recognition of platelets by Ashwell-Morell receptor remains to be determined.

Our original finding that galactosylation of platelets stored short term by refrigeration rescues circulation is contradictory to the notion that galactose recognition by Ashwell-Morell receptors promotes platelet removal. We hypothesize that βGal added to exposed βGlcNAc represents only a very small portion of the total platelet glycans, with the majority remaining fully sialylated. Neuraminidase-treated and transfused murine and rabbit platelets are removed rapidly 41, demonstrating the fundamental importance of immature/desialylated glycans in eliciting Asgr lectin-mediated clearance. Here we demonstrate that the duration of platelet refrigeration influences the nature of glycan exposed, i.e., either βGlcNAc or βGal. It is, therefore, not surprising that lectin receptors on macrophages and/or hepatocytes cooperate to remove refrigerated platelets. The two mechanisms mediating the clearance of refrigerated platelets are summarized in the supplemental material section (Fig. S1).

Future studies will investigate if re-glycosylation, i.e. a combination of galactosylation and sialylation of immature platelet surface glycans, can rescue refrigerated platelet survival to accommodate their refrigeration for transfusion. Inhibition of sialidase activity could also enhance survival of long-term refrigerated platelets. The surprising presence of multiple glycosyltransferases (galactosyltransferases and sialyltransferases) in and on the surface of platelets may have implications for platelet functionality as suggested previously 43,44. It is possible that donor sugars and secreted glycosyltransferases regulate platelet function and survival.

METHODS

Animals

Age-, strain- and sex-matched C57BL/J6 WT mice of ages 5 to 7 weeks were used for all clearance and survival studies (Charles River Laboratories Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Mice were maintained and treated as approved by Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals according to NIH standards as set forth in The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Asgr1−/− mice 45 and Asgr2−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory, stock 002387 46) were provided by Dr. J. D. Marth (University of California, San Diego, CA, USA).

Platelet preparation

We collected human venous blood from healthy volunteers by venipuncture into 1/10 of volume of Aster Jandl citrate-based anticoagulant (85 mM sodium citrate, 69 mM citric acid, 111 mM glucose, pH 4.6). Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifugation at 268 × g for 20 min at room temperature (RT). For long-term storage experiments, human platelet concentrates from individual donors (Reaserch Blood Components, LLC) were stored at 4 °C ≤10 d, without agitation. Platelet rich plasma samples (3 ml) were obtained under sterile conditions at d 0, 2, 5 and 10. Platelets were collected from the PRP by centrifugation at 834 × g for 5 min, washed in platelet buffer (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 12 mM trisodium citrate, 10 mM glucose, and 12.5 mM sucrose, 1 μg ml−1 PGE1, pH 6.0) (buffer A) by centrifugation (834 × g for 5 min) and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 0.5 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4 2 (buffer B).

Approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of both Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard Medical School, and informt consent was approved according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Murine blood isolation, PRP preparation and human or murine platelet labeling are detailed in “Supplemental Methods”.

Platelet temperature and storage protocols

To study the effects of cold on platelet survival and/or function, isolated platelets were incubated for 2 h at ice bath temperatures, a process designated as short-term cooling or as “0° C”, or resuspended in PPP and stored for 48 h at 4 °C (4° C), a process designated as long-term cooling or as “4° C”. All platelets stored in the cold were rewarmed for 15 minutes at 37 °C before use 10. All labeling procedures and enzymatic digestion of platelets with the exception of 111Indium labeling, were performed prior to storage. Freshly isolated platelets (platelets maintained for maximal 2 h at room temperature) in PPP were used as controls for all survival experiments and are designated as fresh platelets or as “22 °C”.

Histology

Mice were infused with 3×109 of biotinylated platelets. Organs were collected 5, 15 30 min and 24 h and were formalin-fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned every 3 μm. The distribution of biotin (biotinylated platelets) was visualized using Strepavidin-POD conjugate and ImmunoHisto™ Peroxidase Detection Kit. Sections were counterstained with H&E according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Quantitative analysis of staining was done in blinded samples. Ten tissue sections were selected from mice having similar levels of injected platelets and scored for hepatocytes and macrophages containing biotinylated platelets.

Macrophage depletion

Mice were depleted of phagocytic cells by a single injection of liposomes containing dichloromethylene bisphosphonate (clodronate liposomes) 15,16. Mice were injected i.v. with 0.02 ml of clodronate liposomes per 10 g body weight 24 h prior to platelet transfusions. This treatment depletes 99% of Kupffer cells and 95% of splenic macrophages 15,16. Staining for macrophages was performed using an antibody to mouse F4/80 (SEROTEC) in tissue sections of clodronate treated and untreated mice. No F4/80 staining was detected following clodronate-liposome treatment (data not shown). Control liposomes were prepared with PBS in place of clodronate.

In vitro HepG2 based platelet ingestion assay is detailed in “Supplemental Methods.”

K-function calculation

X and Y coordinates of particles (COM) were pasted into Microsoft Excel. Macros for K-function analysis were obtained from Dr. John Hancock at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. A plot of L(r)-r vs. r visualized clustering, where the L(r) - r function that has a >99% CI of ± 1 indicates significant clustering or dispersal at the radius r. Values <-1 indicate dispersal whereas values >1 indicate significant clustering 51.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated. Our experiments include imbalanced groups, where the precision of the mean effect depends directly on the sample size, the data is therefore calculated as s.e.m. All numeric data are analyzed for statistical significance using one way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, unless otherwise indicated, with Prism software (GraphPad). We considered P values of less than 0.05 as statistically significant. Degrees of statistical significance are presented as NS > 0.05, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Nayeb-Hashemi for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Henrik Clausen for helpful discussions and Dr. François Maignen for statistical expertise. Supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health grant PO1 HL056949 (to JHH and KMH) and grant HL089224 (to KMH); The Pew Scholars Award to KMH; PO1HL57345 (to JDM); Howard Hughes Medical Institute provided support to JDM; The Swedish Medical Research Council, Göteborg University Jubileums stipend to VR. KMH, VR and HHW received sponsored research support form ZymeQuest, Inc. of Beverly, MA, USA. E.C.J.’s current address is the Walter & Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Molecular Medicine, 1G Royal Parade, 3050 Vic, Parkville, Australia.

Footnotes

Authorship/contribution: VR: wrote manuscript, planned and performed experiments, data analysis and presentation of all figures; PKG: provided Asgr KO mice; performed experiments; HHW: designed research, ECJ: performed and analyzed experiment; ALS: designed research; GL: designed research; JDM: provided Asgr KO mice, laboratory space and equipment; JHH: wrote manuscript, performed experiment: KMH: designed research, wrote manuscript, performed experiments

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.H.W and K.M.H. are consultants for ZymeQuest. H.H.W has stock options in ZymeQuest. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Becker G, Tuccelli M, Kunicki T, Chalos M, Aster R. Studies of platelet concentrates stored at 22°C and 4°C. Transfusion. 1973;13:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.1973.tb05442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmeister K, et al. The clearance mechanism of chilled blood platelets. Cell. 2003;10:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy S, Gardner F. Effect of storage temperature on maintenance of platelet viability -- deleterious effect of refrigerated storage. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:1094–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196905152802004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuehnert M, et al. Transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection in the United States, 1998 through 2000. Transfusion. 2001;41:1493–1499. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41121493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blajchman M. Bacterial contamination of blood products. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2001;24:245. doi: 10.1016/s1473-0502(01)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comprehensive Report on Blood Collection and Transfusion in the United States in 2001. Executive Summary. National Blood Data Resource Center; Bethesda, MD: 2001. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCullough J. Transfusion Medicine. Lipincott Wilkins & Williams; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webert KE, et al. Proceedings of a Consensus Conference: pathogen inactivation-making decisions about new technologies. Transfus Med Rev. 2008;22:1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmeister K, et al. Glycosylation restores survival of chilled blood platelets. Science. 2003;301:1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1085322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wandall HH, et al. Galactosylation does not prevent the rapid clearance of long-term, 4 degrees C-stored platelets. Blood. 2008;111:3249–3256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGill M. Temperature cycling preserves platelet shape and enhances in vitro test scores during storage at 4 degrees. J Lab Clin Med. 1978;92:971–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGill M. Platelet storage by temperature cycling. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1978;28:119–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valeri C, Giorgio A, Macgregor H, Ragno G. Circulation and distribution of autotransfused fresh, liquid-preserved and cryopreserved baboon platelets. Vox Sang. 2002;83:347–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2002.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alves-Rosa F, et al. Macrophage depletion following liposomal-encapsulated clodronate (LIP-CLOD) injection enhances megakaryocytopoietic and thrombopoietic activities in mice. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:130–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rooijen N, van Nieuwmegen R. Elimination of phagocytic cells in the spleen after intravenoous injection of liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate: an enzyme-histochemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238:355–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00217308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooijen N, van Kesteren-Hendrikx E. “In vivo“ depletion of macrophages by liposome-mediated “suicide”. Methods Enzymol. 2003;373:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)73001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josefsson E, Gebhard H, Stossel T, Hartwig J, Hoffmeister K. The macrophage alphaMbeta2 integrin alphaM lectin domain mediates the phagocytosis of chilled platelets. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18025–18032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grewal PK, et al. The Ashwell receptor mitigates the lethal coagulopathy of sepsis. Nat Med. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nm1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berndt M, et al. Purification and preliminary characterization of the glycoprotein Ib complex in the human platelet membrane. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985;151:637–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez J, et al. Cloning of the alpha chain of human platelet glycoprotein Ib: a transmembrane protein with homology to leucine-rich alpha 2-glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 1987;84:5615–5619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji T, et al. The carbohydrate moiety of human platelet glycocalicin. J. Biol.Chem. 1983;258:6335–6339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuji T, Osawa T. The carbohydrate moiety of human platelet glycocalicin: the structures of the major Asn-linked sugar chains. J Biochem. 1987;101:241–249. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezzell R, Kenney D, Egan S, Stossel T, Hartwig J. Linkage of the membrane glycoprotein GPIb to the actin cytoskeleton by a defined domain of actin-binding protein (ABP) in resting and thrombin-activated human platelets. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:211a. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rensen P, et al. Detemination of the upper size limit for uptake and processing of ligands by the asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepacytes in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37577–37584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki K, Lee RT, Lee YC, Kawasaki T. The differences in structural specificity for recognition and binding between asialoglycoprotein receptors of liver and macrophages. Glycoconj J. 1995;12:268–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00731329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlepper-Schafer J, et al. Endocytosis via galactose receptors in vivo. Ligand size directs uptake by hepatocytes and/or liver macrophages. Exp Cell Res. 1986;165:494–506. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb-Bachofen V, Schlepper-Schafer J, Roos P, Hulsmann D, Kolb H. GalNAc/Gal-specific rat liver lectins: their role in cellular recognition. Biol Cell. 1984;51:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322x.1984.tb00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason K, et al. Programmed anuclear cell death delimits platelet life span. Cell. 2007;128:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellies L, et al. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-IV operates as a dominant modifier of hemostasis by concealing asialoglycoprotein receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10042–10047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142005099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmeister K, et al. Mechanisms of Cold-induced Platelet Actin Assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24751–24759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crowe J, et al. Stabilization of membranes in human platelets freeze-dried with trehalose. Chem Phys Lipids. 2003;122:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gousset K, Tsvetkova NM, Crowe JH, Tablin F. Important role of raft aggregation in the signaling events of cold-induced platelet activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1660:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leidy C, et al. Lipid phase behavior and stabilization of domains in membranes of platelets. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2004;40:123–148. doi: 10.1385/CBB:40:2:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergmeier W, et al. Metalloproteinase inhibitors improve the recovery and hemostatic function of in vitro-aged or -injured mouse platelets. Blood. 2003;102:4229–4235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korrel S, et al. Identification of a tetrasialylated monofucosylated tetraantennary N-linked carbohydrate chain in human platelet glycocalicin. FEBS Lettt. 1988;15:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuji T, Osawa T. The carbohydrate moiety of human platelet glycocalicin: the structures of the major Asn-linked sugar chains. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1987;101:241–249. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korrel SA, et al. Structural studies on the O-linked carbohydrate chains of human platelet glycocalicin. Eur J Biochem. 1984;140:571–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward C, Andrews R, Smith A, Berndt M. Mocarhagin, a novel cobra venom metalloproteinase, cleaves the platelet von Willebrandt factor receptor glycoprotein Ibα. Identification of the sulfated tyrosine/anionic sequence Tyr-276-Glu-282 of glycoprotein Ibα as a binding site for von Willebrandt factor and α-thrombin. Biochemistry. 1996;28:8326–8336. doi: 10.1021/bi952456c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergmeier W, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates GPIbalpha shedding from platelets in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res. 2004;95:677–683. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000143899.73453.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denis CV, Christophe OD, Oortwijn BD, Lenting PJ. Clearance of von Willebrand factor. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:271–278. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimers HJ, Greenberg J, Cazenave JP, Packham MA, Mustard JF. Experimental modification of platelet survival. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;82:231–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-4220-5_48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wahrenbrock M, Varki A. Multiple hepatic receptors cooperate to eliminate secretory mucins aberrantly entering the bloodstream: are circulating carcer mucins the “tip of the iceberg”? Cancer Res. 2006;66:2433–2441. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barber A, Jamieson G. Platelet collagen adhesion characterization of collagen glucosyltransferase of plasma membranes of human blood platelets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;252:533–545. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(71)90156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauvois B, et al. Membrane glycoprotein IIb is the major endogenous acceptor for human platelet ectosialyltransferase. FEBS Lett. 1981;125:277–281. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80737-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soukharev S, Miller JL, Sauer B. Segmental genomic replacement in embryonic stem cells by double lox targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishibashi S, Hammer RE, Herz J. Asialoglycoprotein receptor deficiency in mice lacking the minor receptor subunit. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27803–27806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker G, Sullam P, Levin J. A simple, fluorescent method to internally label platelets suitable for physiological measurements. Am. J. Hem. 1997;56:17–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199709)56:1<17::aid-ajh4>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown S, Clarke M, Magowan L, Sanderson H. Constitutive death of platelets leading to scavenger receptor-mediated phagocytosis. A caspase independent program. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5987–5995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kotze HF, Lötter MG, Badenhorst PN, Heyns A.d.P. Kinetics if In-111-Platelets in the Baboon: I. Isolation and labeling of a viable and representative Platelet Population. Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 1985;53:404–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham C, et al. Actin-binding protein requirement for cortical stability and efficient locomotion. Science. 1992;255:325–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1549777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prior IA, Parton RG, Hancock JF. Observing cell surface signaling domains using electron microscopy. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:PL9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.177.pl9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falet H, Ramos-Morales F, Bachelot C, Fischer S, Rendu F. Association of the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1C with the protein tyrosine kinase c-Src in human platelets. FEBS Lett. 1996;383:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laemmli U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (Lond) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.