Abstract

Objectives

Rates of preventive asthma care after an asthma emergency department (ED) visit are low among inner-city children. The objective of this study was to test the efficacy of a clinician and caregiver feedback intervention (INT) on improving preventive asthma care following an asthma ED visit compared to an attention control group (CON).

Methods

Children with persistent asthma and recent asthma ED visits (N = 300) were enrolled and randomized into a feedback intervention or an attention control group and followed for 12 months. All children received nurse visits. Data were obtained from interviews, child salivary cotinine levels and pharmacy records. Standard t-test, chi-square and multiple logistic regression tests were used to test for differences between the groups for reporting greater than or equal to two primary care provider (PCP) preventive care visits for asthma over 12 months.

Results

Children were primarily male, young (3–5 years), African American and Medicaid insured. Mean ED visits over 12 months was high (2.29 visits). No difference by group was noted for attending two or more PCP visits/12 months or having an asthma action plan (AAP). Children having an AAP at baseline were almost twice as likely to attend two or more PCP visits over 12 months while controlling for asthma control, group status, child age and number of asthma ED visits.

Conclusions

A clinician and caregiver feedback intervention was unsuccessful in increasing asthma preventive care compared to an attention control group. Further research is needed to develop interventions to effectively prevent morbidity in high risk inner-city children with frequent ED utilization.

Keywords: Management/control, pediatrics, prevention

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease affecting 7.1 million U.S. children and is the number one cause of pediatric emergency department (ED) visits [1–4]. The cornerstone of treatment for persistent asthma is inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) [5]. When ICS medications are prescribed and used properly, they can prevent acute exacerbations and maintain asthma control [6–8]. Yet, less than 50% of inner-city children with asthma receive or use recommended anti-inflammatory preventive medications [9–11]. One major reason for poor anti-inflammatory medication use is the low rate of preventive asthma follow-up with a primary care provider/physician (PCP) for children with frequent ED asthma visits [8,12–14]. Lack of appropriate preventive asthma care results in under-treatment of persistent or uncontrolled asthma [15] and subsequent increased morbidity and mortality [9].

Several strategies focused on enhancing communication with the child’s PCP have been associated with improved preventive asthma care in inner-city children. Timely communication with a child’s PCP via a letter of child asthma health information, including asthma control level and recommendations for guideline-based care, resulted in a significant decrease in ED visits but not in symptom days for inner-city children with moderate to severe asthma [16]. Prompting PCPs about asthma severity with guideline-based recommendations yielded increased discussion of asthma prevention, increased use of AAPs and increased rate of initiating or stepping up preventive asthma medications in low income children [16,17]. However, few interventions have concurrently targeted both the PCP and caregiver to improve access to preventive asthma care by providing information about the child’s level of asthma control, medication use and environmental exposures, such as second hand smoke (SHS). The objective of this study was to test the efficacy of a clinician and caregiver feedback intervention on increasing the rate of preventive asthma visits after an asthma ED visit compared to an attention control group (CON) in inner-city children with asthma.

Methods

This was a prospective randomized controlled trial that was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Medical Institution and the University of Maryland Medical Institutional Review Boards. Children were recruited from two urban pediatric hospital EDs in Baltimore, Maryland, using attendance records. Contact information was obtained for children with recent ED asthma visits using a HIPAA waiver, and a letter was sent to families requesting permission to recruit participants. Families who did not return the letter or call to opt out of recruitment were contacted. Between December 2008 and January 2010, 300 children aged three to ten years with physician diagnosed persistent asthma [5] who reported controller medication use or had two or more ED asthma visits over the past 12 months were enrolled along with their caregivers. After written informed caregiver consent was obtained and child verbal assent (age > 8 years) completed, children were randomly assigned using random-number generation and stratified by child age (3–5 versus 6–10 years) to the feedback intervention (INT) or attention control (CON) group via opaque sealed envelopes viewed by the study coordinator. Children were excluded if they had other respiratory conditions that could interfere with asthma outcomes, such as cystic fibrosis or bronchopulmonary dysplasia. All study personnel, excluding the study coordinator and nurse interventionists, were blinded to group assignment. All child participants were followed over 12 months using face-to-face interview questionnaires, pharmacy fill data and child salivary cotinine levels as a biomarker for second hand smoke (SHS) exposure.

Description of the interventions

All enrolled children received three nurse visits by a specially trained community health nurse over 4 months with a different location of one of the visits for the INT group. Children and caregivers assigned to the attention control (CON) group received asthma education only during three home visits, including the identification of asthma triggers, medication device training, environmental control education and the importance of controller medication use and preventive asthma care. Caregivers of children assigned to the CON received their child’s level of exposure to SHS (cotinine concentration) and tips for implementing a total home smoking ban [18], by mail at the end of the study.

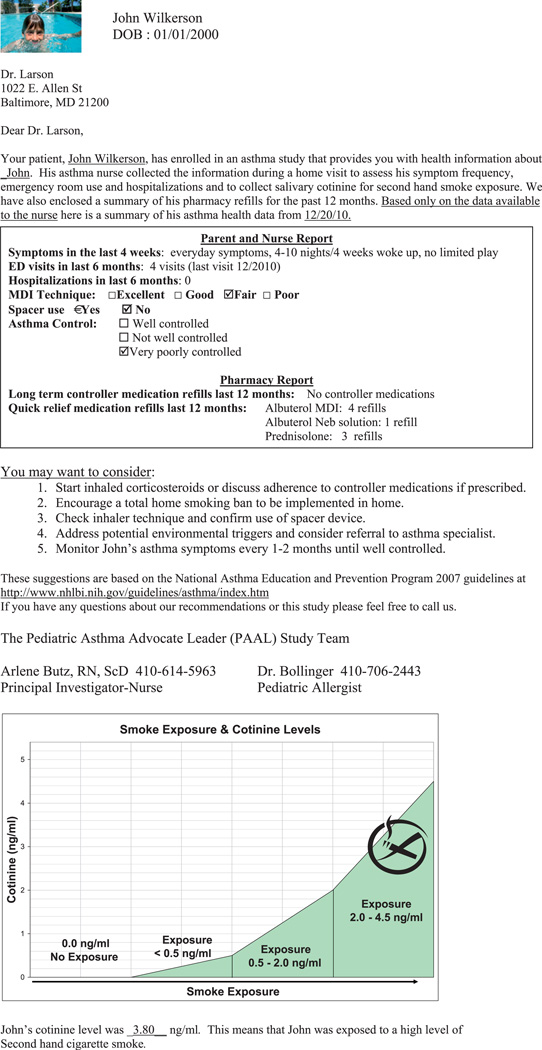

For children in the INT group, the caregiver received asthma education during two home visits including the same topics as the CON group. Additionally during the home visits, the INT nurse reviewed the caregiver feedback letter that explained the number of the child’s asthma medication fills over the past 12 months, the child’s cotinine concentration, and tips for implementing a total home smoking ban. For the third INT nurse visit, the nurse joined the caregiver and child at the PCP office for a preventive asthma care visit. During the PCP visit, the nurse delivered a separate clinician feedback letter to the PCP explaining the child’s report of symptom days, inhaler technique, asthma medication fills and cotinine concentration (Figure 1). In addition, the nurse prompted the PCP to deliver a controller medication prescription, address SHS exposure for children with any exposure and sign a prepared AAP form. The PCP feedback letter included (1) a summary of the child’s symptom frequency, inhaler technique, asthma control and pharmacy fill report, (2) the child’s cotinine level and (3) recommendations for preventive care based on national asthma guidelines [5]. All feedback letters were developed and signed by a pediatric allergist and a primary care pediatrician. After each PCP visit, the nurse completed an intervention clinic checklist recording (1) PCP review of feedback letter, (2) nurse discussion of controller and rescue medication fills, (3) nurse and parent discussion of cotinine level with PCP and home smoking ban counseling and (4) PCP review of the prepared AAP. Fidelity of the INT and CON interventions were measured by review of manualized nurse visit forms [19] during bi-weekly supervision with INT and CON nurses to discuss issues that may have hindered delivery of the intervention. Co-visits with nurses by senior nurse investigators occurred during 10% of visits.

Figure 1.

Example of Clinician Feedback Letter (Patient name anonymous).

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) [20,21] served as the conceptual framework for the feedback intervention. The CCM is a primary care-based framework to improve care of chronically ill patients and by definition is designed to foster more productive interactions between prepared, proactive primary care teams and well-informed, motivated patients [20–22]. Our feedback intervention targeted four of the six CCM elements associated with high-quality care: provider decision support, clinical information systems, community linkage and resources and caregiver self-management support to improve interactions between PCP and caregiver. The intervention was not designed to address the health care organization or delivery system design elements of the CCM.

Measurement of variables

Health outcome measures

The primary outcome for this study was the number of preventive asthma care visits with a PCP and the secondary outcome was the number of ED visits over 12 months. Caregivers reported the number of PCP visits for preventive asthma care and ED visits for the past 6 months at every 6-month data point. A summary variable for the number of PCP and ED visits was calculated at 12 months. Additional health outcomes included asthma severity and control. Asthma severity was based on the day and night time symptom frequency over the past two weeks using national asthma guidelines [5]. Asthma control categories (well controlled, not well controlled or very poorly controlled) were based on the number of symptom days and nights, rescue medication use, activity limitation and number of ED visits and hospitalizations. The use of an AAP in the home was assessed every 6 months.

Asthma medication use

Pharmacy dispensation records of asthma medications dispensed over a year were obtained at baseline and at 12 months. Pharmacy records included the dispensing date, product name, strength, dosage form and quantity dispensed. Rescue medications were defined as short acting B-agonists (SABA) and controller medications were defined as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), leukotriene modifiers (LTM), long acting beta agonists (LABA) and mast cell stabilizers. Oral corticosteroid (OCS) prescription fills were analyzed separately. As a proxy of appropriate controller medication use, ratios of controller to total asthma medications were calculated at the 12 month follow-up, i.e. the total number of controller medication canisters or equivalents as the numerator and the total number of controller and SABA canisters or equivalents filled as the denominator [23]. Ratios of 0.50 or higher have been associated with decreased asthma morbidity and quality of life [23]. Caregiver report of controller medication use was recorded at baseline and 12 months.

Second hand smoke exposure

Second hand smoke (SHS) is a known preventable environmental trigger of asthma and airway inflammation and was targeted in the INT protocol to motivate caregivers and PCPs to reduce the child’s SHS exposure. Child saliva samples were collected for cotinine analysis as a biomarker of SHS exposure over the prior 24 h. Two small sorbettes with mini sponges were placed under the child’s tongue, collected and stored at −20 °C. All samples were analyzed at Salimetrics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, using enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) analysis. The lower limit of cotinine sensitivity was 0.05 ng/ml and average intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 5.8 and 7.9%, respectively. A cotinine cutoff level of 1.0 ng/ml was used to define positive SHS exposure based on a comparable sample of inner-city children with asthma [24,25].

Statistical analysis

Assuming 90% power for a two-sided test with an alpha of 0.05, we estimated a sample size of 120 per group (total = 240) to detect a 0.18 absolute difference in proportion of children with more than two PCP visits over 12 months or the primary outcome (INT = 0.70 versus CON = 0.52). We enrolled 300 children in order to detect the 0.18 difference between the CON and INT groups and account for a 19% attrition rate based on our prior follow-up rates [11]. Standard frequencies, t-test and chi-square tests were used to confirm balance between INT and CON groups for baseline demographic and health variables. The intention-to-treat analysis included all of the randomly assigned study participants to compare the number of PCP preventive asthma visits over 12 months, the primary outcome, by group status. PCP preventive asthma visits were categorized as 0–1 visits (poor preventive asthma care) versus two or more visits (appropriate preventive care). The cutoff at two or more PCP visits was based on national guideline recommendations for asthma preventive care follow-up at 1-to-6-month intervals, or a minimum of two visits per 12 months [5]. Symptom-free days (SFDs) were calculated for the baseline and 12-month time points by subtracting the number of days of asthma symptoms over 2 weeks from 14 days. Several logistic regression models were tested to predict two or more PCP preventive asthma visits over 12 months, while adjusting for group status (INT versus CON), child age, medication ratio, asthma control and total ED visits over the 12-month follow-up, and caregiver education, marital status, employment and depressive symptoms. Because a subgroup of INT children failed to complete the full intervention (not attend the PCP visit with the INT nurse), a secondary analysis was conducted across three groups: INT children who completed the full intervention (INT-completers), INT children not completing the PCP component of the intervention (INT-non-completers) and controls (CON). Two-sided tests were used and p values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using procedures in SAS Version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) [26] and SPSS Version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) [27] software.

Results

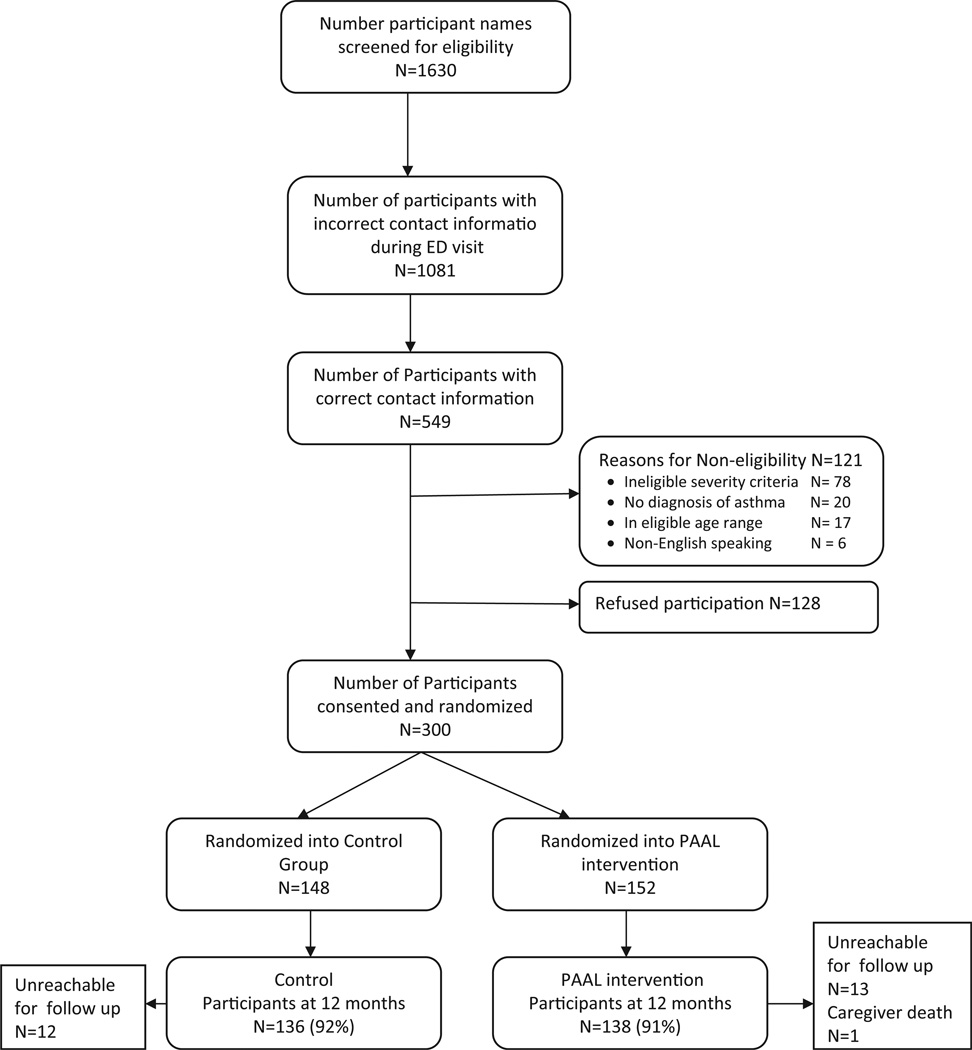

Of the 1630 eligible children identified in the pediatric ED, 1081 (66%) had incorrect contact information based on ED records (Figure 2). Out of the remaining 549 children, 300 (70%) eligible children were enrolled and randomized (CON: n = 148; INT: n = 152). No difference was noted in child age, gender, race/ethnicity, Medicaid insurance rate or zip code between a subsample of non-enrollees randomly selected from eligible children (n = 103) versus enrolled children (data not shown). At the 12-month follow-up, 274/300 (91%) of children had complete interview, pharmacy fill and cotinine data. As shown in Table 1, the children were primarily male, African American, preschool aged and Medicaid insured and the majority resided with a smoker (59%). Caregivers were predominantly single, unemployed, high school educated and were the primary household smoker (59%). Prevalence of child SHS exposure was high (57%) based on cotinine levels > 1.0 ng/ml [24,25]. Treatment groups did not differ at baseline by sociodemographic, health characteristics, having an AAP, pharmacy fill rates or mean cotinine levels.

Figure 2.

Recruitment and Retention flow diagram for 12-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and asthma health characteristics by intent-to-treat groups.

| Control (N = 148) N (%) |

Intervention (N = 152) N (%) |

Overall (N = 300) N (%) |

Statistics | |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 86 (58.1) | 92 (60.5) | 178 (59.3) | X2 = 0.18, df = 1, p = 0.67 |

| Female | 62 (41.9) | 60 (39.5) | 122 (40.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity (N = 299) | ||||

| African American | 142 (96.6) | 144 (94.7) | 286 (95.7) | X2 = 0.62, df = 1, p = 0.43 |

| White/Hispanic/other | 5 (3.4) | 8 (5.3) | 13 (4.3) | |

| Age | ||||

| 3–5 years | 82 (55.4) | 84 (55.3) | 166 (55.3) | X2 = 0.001, df = 1, p = 0.98 |

| 6–10 years | 66 (44.6) | 68 (44.7) | 134 (44.7) | |

| Type of medical insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | 137 (92.6) | 138 (90.8) | 275 (91.7) | X2 = 1.12, df = 2, p = 0.57 |

| Private/self-pay | 11 (7.4) | 14 (9.2) | 24 (8.0) | |

| Caregiver characteristics | ||||

| Relationship to child | ||||

| Birth mother | 135 (91.8) | 141 (92.8) | 276 (92.3) | X2 = 3.97, df = 2, p = 0.14 |

| Birth father | 7 (4.8) | 2 (1.3) | 9 (3.0) | |

| Other relative | 5 (3.4) | 9 (5.9) | 14 (4.7) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 108 (73.5) | 102 (68.0) | 210 (70.7) | X2 = 1.07, df = 2, p = 0.58 |

| Married | 25 (17.0) | 31 (20.7) | 56 (18.9) | |

| Divorced/widow/other | 14 (9.5) | 17 (11.3) | 31 (10.4) | |

| Education | ||||

| <High School | 46 (31.3) | 43 (28.3) | 89 (29.8) | X2 = 1.40, df = 2, p = 0.50 |

| High School grade | 60 (40.8) | 57 (37.5) | 117 (39.1) | |

| >High school (technical/college) | 41 (27.9) | 52 (34.2) | 93 (31.1) | |

| Employed | ||||

| Yes | 69 (47.6) | 65 (43.3) | 134 (45.4) | X2 = 0.538, df = 1, p = 0.46 |

| Poverty status of household at baselinea | ||||

| Above Poverty level | 7 (5.5) | 15 (11.3) | 22 (8.5) | X2 = 3.82, df = 2, p = 0.15 |

| At Poverty Level | 15 (11.8) | 10 (7.5) | 25 (9.6) | |

| Below Poverty Level | 105 (82.7) | 108 (81.2) | 213 (81.9) | |

| Number of household smokers | ||||

| None | 57 (38.5) | 66 (43.4) | 123 (41.0) | X2 = 1.10, df = 2, p = 0.58 |

| 1 | 51 (34.5) | 52 (34.2) | 103 (34.3) | |

| 2 or more | 40 (27.0) | 34 (22.4) | 74 (24.7) | |

| Caregiver is smoker | ||||

| Yes | 52/91 (57.1) | 52/86(60.5) | 104/177 (58.8) | X2 = 0.20, df = 1, p = 0.65 |

| Asthma health characteristics | ||||

| Asthma severity at baseline | ||||

| Mild intermittent | 9 (6.1) | 6 (4.0) | 15 (5.0) | X2 = 4.55, df = 3, p = 0.21 |

| Mild persistent | 49 (33.3) | 65 (43.0) | 114 (38.3) | |

| Moderate persistent | 24 (16.3) | 28 (18.5) | 52 (17.4) | |

| Severe persistent | 65 (44.2) | 52 (34.4) | 117 (39.3) | |

| Asthma control at baselineb | ||||

| Not well controlled | 9 (6.1) | 11 (7.2) | 20 (6.7) | X2 = 0.16, df = 1, p = 0.69 |

| Very poorly controlled | 139 (93.9) | 141 (92.8) | 280 (93.3) | |

| ED Visits last 6 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.22 (3.1) | 3.25 (3.3) | 3.23 (3.2) | t = −0.074, p = 0.94 |

| Symptom-free days past 14 daysc | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.28 (5.4) | 7.22 (5.2) | 6.76 (5.3) | t = −1.53, p = 0.13 |

| Symptom-free nights past 14 daysc | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.91 (5.7) | 7.86 (5.5) | 7.39 (5.6) | t = −1.46, p = 0.16 |

| Asthma action plan in home | ||||

| Yes | 53 (36.8) | 50 (33.8) | 103 (35.3) | X2 = 0.29, df = 1, p = 0.59 |

| Cotinine level | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.68(3.2) | 2.80 (3.8) | 2.74 (3.5) | t = −0.28, p = 0.78 |

| ≥1.0 (positive) | 85 (59.0) | 80 (54.8) | 165 (56.9) | X2 = 0.53, df = 1, p = 0.47 |

| N (SD) | N (SD) | N (SD) | ||

| Pharmacy fills past (12 months prior to baseline) | ||||

| ICS fills prior 12 months | 1.80 (2.1) | 1.59 (2.0) | 1.68 (2.1) | t = 0.73, p = 0.39 |

| SABA fills prior12 months | 3.07 (2.9) | 2.94 (3.1) | 3.00 (3.0) | t = 0.13, p = 0.72 |

| Leukotriene Modifier fills prior 12 months | 1.02 (2.0) | 0.89 (1.6) | 0.95 (1.8) | t = 0.30, p = 0.58 |

| ICS/LABA combination fills at 12 months | 0.14 (0.7) | 0.18 (0.7) | 0.16 (0.7) | t = 0.16, p = 0.69 |

| OCS fills prior 12 months | 1.59 (1.5) | 1.41 (1.5) | 1.49 (1.5) | t = 0.86, p = 0.35 |

| Medication Ratio | 0.31 (0.2) | 0.30 (0.2) | 0.30 (0.2) | t = 0.49, p = 0.62 |

Above poverty level = 200% of poverty level, At poverty level = 100% of poverty level, Below poverty level = less than 100% poverty level.

No participants classified with “Well Controlled” at baseline.

Number of days reported over 2 weeks (range 0–14).

Overall, delivery of the nurse interventions was high with the majority of CON (88%) and INT (71%) families receiving all three nurse visits, i.e. CON received three home visits and INT received two home visits and one clinic co-visit. Multiple nurse contacts (e.g. phone calls and attempted home visits) were required to deliver the study protocol to both groups, but the number of nurse contacts did not differ by INT or CON group (Mean [SD] contacts: INT, 8.30 contacts [3.6]; CON, 7.59 contacts [4.3]; t = −1.57, p = 0.12). Mean completed nurse visits were significantly higher for the CON group (Mean [SD] visits: CON, 2.76 [0.7]; INT, 2.59 [0.6]; ALL children, 2.68 [0.68], t = 2.186, p = 0.03) (data not shown). Despite efforts by INT nurses to reduce barriers to attending PCP visits, a subset of INT children (n = 44, 29%) did not complete the scheduled PCP visit component of the intervention, but did complete the two nurse home visits. All children had a PCP on record for follow-up at the index ED visit. Reasons for non-completion of the PCP visits included caregiver stressful life events such as hospitalization or death of a family member, difficulty scheduling PCP visits due to conflicts with caregiver work schedule, child school priorities and a lack of belief in preventive care by caregiver. Anecdotal data from nurse logs also suggested that mental health and substance abuse problems in the family system may have contributed to the low PCP visit completion rate. For those children attending the visit, PCP actions during the visit recorded by the nurse in response to the feedback intervention were moderately consistent. The majority of PCPs: (1) reviewed the feedback letter (70%), (2) discussed the child’s controller and rescue medication fill rates with parent (68%), (3) discussed cotinine level with parent (58%) and (4) reviewed completed AAPs (88%). There was no association between the PCP discussing the child’s cotinine level and a low cotinine level at 12 months (<1.0 ng/ml; X2 = 0.65, p = 0.42). No adverse events occurred in either group.

Impact of caregiver and PCP feedback intervention

Overall, most children in both groups remained very poorly controlled (62%), continued with high ED use over the 12-month follow-up (mean: 2.29 ED visits over 12 months), and experienced only 2–3 additional symptom free days (SFDs) over the 12-month follow-up (Table 2). Most children in the total group reported two or more PCP visits over the follow-up (76%) and only 65% reported having an AAP in the home. Comparison by group (CON versus INT) indicated no differences in the level of asthma control, mean ED or PCP visits or mean change in SFDs asthma morbidity, health care utilization, cotinine level or having an AAP in the home over the 12-month follow-up. Despite 88% of INT caregivers reviewing an AAP with the child’s PCP, only 62% reported having one in the home.

Table 2.

Asthma morbidity, health care utilization and medication use at 12 months by group.

| Control (N = 136) N (%) |

Intervention (N = 138) N (%) |

Overall (N = 274) N (%) |

Statistics | |

| Asthma morbidity and health care utilization outcomes | ||||

| Symptom Free Days past 14 daysa | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.74 (4.8) | 9.15 (5.2) | 9.44 (5.0) | t = 0.97, p = 0.34 |

| Change in Symptom Free Days from baseline to 12 monthsa | ||||

| Mean (SD) | +3.51 (7.0) | +2.15 (6.8) | +2.83 (6.9) | t = 1.62, p = 0.11 |

| Symptom free nights past 14 daysa | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.01 (5.2) | 10.49 (4.7) | 10.25 (4.9) | t = −0.81, p = 0.42 |

| Asthma Control | ||||

| Well controlled | 21 (15.4) | 18 (13.1) | 39 (14.3) | X2 = 0.80, df = 2, p = 0.67 |

| Not well controlled | 30 (22.1) | 36 (26.3) | 66 (24.2) | |

| Very poorly controlled | 85 (62.5) | 83 (60.6) | 168 (61.5) | |

| Total ED visits over 12 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.24 (2.7) | 2.34 (2.7) | 2.29 (2.7) | t = −0.28, p = 0.78 |

| Total Hospitalizations over 12 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.45 (0.9) | 0.35 (1.0) | 0.40 (1.0) | t = 0.82, p = 0.42 |

| Number of PCP visits over 12 months | ||||

| 0–1 visit | 35 (26.7) | 29 (21.5) | 64 (24.1) | X2 = 1.00, df = 1, p = 0.32 |

| 2 or more visits | 96 (73.3) | 106 (78.5) | 202 (75.9) | |

| Cotinine exposure | ||||

| ≥1.0 (positive) | 78 (58.2) | 77 (56.6) | 155 (57.4) | X2 = 0.07, df = 1, p = 0.79 |

| Asthma action plan in the home (YES) | 91 (66.9) | 86 (62.3) | 177 (64.6) | X2 = 0.63, df = 1, p = 0.43 |

| Medication use | ||||

| Controller medicine use (Parent report) | ||||

| Yes | 119 (86.9) | 119 (86.9) | 238 (86.9) | X2 = 0.10, df = 1, p = 0.76 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Statistics | |

| Pharmacy fills | ||||

| ICS fills at 12 months | 3.55 (3.5) | 3.39 (3.9) | 3.46 (3.7) | t = 0.35, p = 0.73 |

| Mean change in ICS fills from baseline to 12 months | 1.92 (2.9) | 1.76 (2.9) | 1.83 (2.9) | t = 0.44, p = 0.66 |

| SABA fills at 12 months | 5.97 (5.2) | 6.09 (5.5) | 6.03 (5.4) | t = −0.18, p = 0.85 |

| Mean change in SABA fills from baseline to 12 months | 3.00 (3.7) | 3.07 (3.5) | 3.04 (3.6) | t = −0.15, p = 0.88 |

| Leukotriene modifier (LTM) fills at 12 months | 2.94 (4.4) | 2.39 (4.0) | 2.66 (4.2) | t = 1.19, p = 0.28 |

| Mean change in LTM fills from baseline to 12 months | 1.88 (4.8) | 1.50 (4.1) | 1.67 (4.4) | t = 0.68, p = 0.49 |

| OCS fills at 12 months | 2.64 (2.4) | 2.28 (2.5) | 2.45 (2.4) | t = 1.21, p = 0.23 |

| Medication ratio | 0.38 (0.2) | 0.36 (0.2) | 0.37 (0.2) | t = 0.52, p = 0.60 |

Number of days reported over 2 weeks (range 0–14).

Mean ICS and LTM fills over 12 months remained low at 3.46 (SD 3.7) and 2.66 (SD 4.2), respectively, for all children indicating intermittent use. There were no differences in ICS or LTM fills by group at 12 months. Alternatively, rescue medication use was high for all children with mean SABA fills at 6.0 fills and oral corticosteroid fills at 2.45 fills over 12 months. There were no difference in SABA or oral corticosteroid fills by group. Use of ICS and long acting beta agonist combination medications were low for all children at 13%.

Several multivariate logistic regression models were tested to predict two or more PCP asthma preventive care visits over 12 months. In the final regression model, children having an AAP at baseline were almost two times more likely to attend two or more primary care asthma preventive care visits over 12 months while controlling for treatment group, child age, asthma control level and number of ED visits over 12 months (Table 3). Attending two or more ED visits over the 12 months trended toward predicting two or more primary care asthma preventive care visits over 12 months. Intervention status was not significantly associated with attending two or more primary care asthma preventive care visits over 12 months. The model indicated goodness of fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow p = 0.35). Prior models including predictors of caregiver employment, marital status and cotinine levels were not statistically significant for predicting two or more primary care asthma preventive care visits.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model for predicting 2 or more PCP visits for preventive asthma care over 12 months.

| Model 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | Standard error | Wald | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Child age | |||||

| 6–10 versus 3–5 years (Reference = 3–5 years) | −0.39 | 0.30 | 1.57 | 0.69 (0.38,1.24) | 0.21 |

| Asthma control at 12 months | |||||

| Not well controlled versus well controlled | 0.71 | 0.47 | 2.22 | 2.03 (0.80, 5.13) | 0.14 |

| Very poorly controlled versus well controlled (Reference = Well controlled) | 0.42 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 1.53 (0.67, 3.49) | 0.31 |

| Total ED visits over follow-up | |||||

| 2 or more versus 0–1 visits (Reference = 0–1 ED visits) | 0.62 | 0.32 | 3.69 | 1.85 (0.99, 3.47) | 0.06 |

| Treatment group | |||||

| INT versus CON (Reference = Control) | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.89 | 1.33 (0.74, 2.39) | 0.35 |

| Asthma action plan in home at baseline | |||||

| Yes (Reference = No) | 0.67 | 0.33 | 3.98 | 1.95 (1.01, 3.74) | 0.05 |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 8.93, df = 8, p = 0.35 | ||||

To further understand the lack of significance in the number of PCP visits for asthma over 12 months by group, a secondary analysis was conducted to compare INT non-completers separately from the total INT group to examine attending two or more PCP asthma preventive visits over 12 months, i.e. guideline-based preventive care. Children were categorized as (1) INT-completers, (2) INT non-completers (no nurse facilitated PCP visit) and (3) the CON group. Significantly more INT-completers attended two or more PCP asthma preventive care visits over the 12 month follow-up compared to INT–non-completers and the CON group (INT-Completers: 84.8%, CON: 73.3%, INT–Non-Completers: 61.1%; X2 = 9.14, df = 2, p = 0.01). Comparison of the CON group with each INT sub-group revealed that significantly more INT-completers attended two or more PCP preventive asthma visits than the CON group (p = 0.04) but there was no difference in attending two or more PCP visits between the CON and the INT non-completers (p = 0.16).

Discussion

In this select population of high risk young, inner-city children with asthma, a complex clinician and caregiver feedback intervention delivered by community nurses did not increase preventive asthma care visits as compared to an attention control group. Although this intensive feedback intervention provided timely delivery of individualized clinical data and specific recommendations for both caregivers and clinicians to promote more productive interactions with well-informed caregivers, it was not successful in increasing preventive asthma care visits when compared to an attention control group also receiving home nurse visits. Similarly, control children reported a comparable increase in receipt of a written AAP as the INT group. This suggests that the control group caregivers may have benefited from three nurse home visits that provided asthma education and increased self-management support for their child’s asthma, as noted in prior home-visiting programs [28]. Anecdotally, the nurses in our study reported that families in both groups were highly receptive to home visits and a strong relationship of trust, open communication and shared decision making developed between caregiver and nurse over two-three visits. Interestingly, almost all intervention children who did not attend the protocol required PCP visit (e.g. the intervention non-completers), did complete the required nurse home visits. Reaching this sub-group of children who are at highest risk for low rates of preventive asthma care, may require that services be delivered directly to them and their caregivers in the context of their homes.

It is important to note, however, that while children in both groups improved clinically, they continued to suffer from significant asthma morbidity, with the majority remaining poorly controlled at follow-up. For some families, preventive health care is not prioritized, and/or barriers to preventive care are difficult to overcome even with support [29]. Other reasons for intervention ineffectiveness may include our enrollment of young children with frequent ED utilization, known to be at very high risk for asthma morbidity. Further, there are many complex steps required for a child to receive appropriate guideline-based asthma care [30], and not all were addressed in this program.

High SHS exposure was detected in over half of children (59%) and was not reduced after the 12-month intervention, nor did exposure differ by group. This rate of SHS exposure is comparable to a hospital-based sample of low income children with asthma [31], but slightly lower than the 68% reported in community based screening of urban children with asthma [24]. Given that SHS exposure in children with asthma has been associated with increased risk for development and severity of asthma [32] and chronic airway inflammation [33], this high rate of SHS exposure may have contributed to the continued high rate of poor asthma control at 12 months. While feedback regarding the child’s cotinine level was presented to the caregiver and the PCP, the intervention did not include specific caregiver smoking cessation counseling beyond referral to quit lines and free smoking cessation classes. Alternately, caregiver misconception of the ubiquitous penetration of SHS in their home and/or residing in multiunit dwellings may have prohibited reducing cotinine levels some children assigned to the intervention [34]. A subset of children assigned to the intervention group (INT) failed to complete the protocol by not attending the scheduled PCP follow-up visit. This group likely represents the highest risk children for whom preventive care is difficult to implement. Non-completers were characterized as older children (6–10 years old) and less likely to have an AAP at baseline or attend two or more PCP visits over the 12-month follow-up, resulting in potential risk for unscheduled office visits, hospitalization and ED visits. Older children may be less likely than younger children to attend a PCP visit due to competing school obligations. Further, caregivers of older children may allow the child to self-manage their asthma and be less attentive to an older child’s recurrent symptoms [18].

Notably, children having an AAP at baseline were almost two times more likely to have two or more PCP visits over 12 months, which is consistent with prior data indicating that having an AAP in the home is associated with substantially higher medical follow-up in children after asthma ED visit [35]. It is concerning that 88% of the INT caregivers discussed the AAP during their PCP visit per the nurse record, yet only 62% of INT caregivers reported having an AAP in the home. This discrepancy suggests either lack of awareness and/or appreciation of an AAP in the home. The presence of an AAP in the home indicates a prior connection to preventive asthma care, however it may not necessarily equate to delivery of preventive actions by a clinician. In a group of Medicaid insured urban children with persistent asthma who attended a pediatric visit, receipt of preventive care was low; only 19% of caregivers reported that their child received a preventive medication action such as a prescription for a new or step up in controller medication therapy [15]. Yet, children who received an AAP and a prescription for a controller medication in the ED had a substantially higher medical follow-up after an asthma ED visit [35].

The Chronic Care Model [20,21] advocates fostering more productive interactions between prepared, proactive primary care teams and well-informed, motivated patients [20–22]. This intervention targeted clinician decision support by providing timely asthma health information and recommendations to the clinician, prompting the clinician to prescribe a controller medication and promoting caregiver self-management with the goal of improving interactions between the clinician and caregiver. However, we did not anticipate the level of non-adherence to follow-up care with the clinician in a subset of families. To increase the likelihood of optimal asthma preventive care visits, more targeted and individualized interventions may be necessary to engage caregivers who have substantial barriers to primary care. Our experience with inner-city low-income caregivers suggests that screening and intervening on caregiver major life stressors, that may impede the delivery of care, are perhaps a critical precursor to establishing productive interactions among primary care teams and informed and motivated caregivers.

There are several limitations to be considered with this study. Use of an AAP and controller medication may be overestimated based on caregiver self-report. However, agreement between caregiver report and medical record for AAPs and preventive medication actions was high (77% and 85%, respectively) [15]. While we compared an intensive clinician- and home-based nurse intervention with an attention control group who also received home visits, we did not compare the intervention to a usual care group. The original study was designed to test the efficacy of a multifaceted intervention and to determine if the intervention was more efficacious than a less intensive intervention in increasing preventive asthma care and reducing morbidity in high-risk children. The study was not designed as a comparative effectiveness study of usual asthma care. Although we obtained pharmacy records regarding the number of prescriptions dispensed over 12 months, we are unable to determine actual medication use. However, prescription records have been shown to be a reliable source of drug exposure [36]. Finally, generalizability is limited in that we purposely recruited children with more severe or uncontrolled asthma in order to maximize our ability to detect a difference in preventive visits.

Conclusion

In summary, an intensive clinician and caregiver feedback intervention that included home and nurse facilitated follow-up PCP visits was no more successful than a home-based nurse asthma education intervention in improving the number of preventive asthma care visits for inner-city children with persistent asthma. More targeted interventions for caregivers of high-risk children with asthma, delivered in the clinic or in the context of their home, may be necessary to prevent morbidity and increase preventive asthma care for these children.

Acknowledgements

We extend particular thanks to Dr. Marilyn Winkelstein for editorial review. In addition, we thank the families for their participation in this study.

All phases of this study were supported by a National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH grant NR010546.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This clinical trial is registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov and registration number is NCT00860418.

References

- 1.Bloom B, Dey AN. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey 2004. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2006;10:4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, Liu X. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;94:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of childhood asthma in the United States, 1980–2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S131–S145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. National Surveillance for Asthma – United States 1980–2004. MMWR. 2007;56:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.USDHHS. The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. 2007 NIH Publication No. 07-4051. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karnick P, Margellos-Anst H, Seals G. The pediatric asthma intervention: a comprehensive cost-effective approach to asthma management in a disadvantaged inner-city community. J Asthma. 2007;44:39–44. doi: 10.1080/02770900601125391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention: Revised 2010. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2010. [last accessed 16 July 2013]. Available from: www.ginasthma.org. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarfone RJ, Zorc JJ, Capraro GA. Patient self-management of acute asthma: adherence to national guidelines a decade later. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1332–1338. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butz AM, Tsoukleris M, Donithan M, Hsu VD, Mudd K, Zuckerman IH, Bollinger ME. Patterns of inhaled anti-inflammatory medication use in young underserved children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2504–2513. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halterman JS, Auinger P, Conn KM, Lynch K, Yoos HL, Szilagyi PG. Inadequate therapy and poor symptom control among children with asthma: findings from a multistate sample. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butz AM, Tsoukleris MG, Donithan M, Hsu VD, Zuckerman I, Mudd KE, Thompson RE, et al. Effectiveness of nebulizer use-targeted asthma education on underserved children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:622–628. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.6.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma-United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zorc JJ, Scarfone RJ, Li Y. Scheduled follow-up after a pediatric emergency department visits for asthma: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111:495–502. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leickly FE, Wade SL, Crain E, Kruszon-Moran D, Wright EC, Evans R., III Self-reported adherence, management behavior, and barriers to care after an emergency department visits by inner city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1998;101:e8. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yee AB, Fagnano M, Halterman JS. Preventive asthma care delivery in the primary care office: missed opportunities for children with persistent asthma symptoms. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kattan M, Crain EF, Steinbach S, Visness CM, Walter M, Stout JW, Evans R, III, et al. A randomized clinical trial of clinician feedback to improve quality of care for inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1095–e1103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halterman JS, Fisher S, Conn KM, Fagnano M, Lynch K, Marky A, Szilagyi PG. Improved preventive care for asthma: a randomized trial of clinician prompting in pediatric offices. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2006;160:1018–1025. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butz AM, Halterman JS, Bellin M, Kub J, Frick KD, Lewis-Land C, Walker J, et al. Factors associated with successful delivery of a behavioral intervention in high-risk urban children with asthma. J Asthma. 2012;49:977–988. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.721435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumas JE, Lynch AM, Laughlin JE, Phillips SE, Prinz RJ. Promoting intervention fidelity. Conceptual issues, methods and preliminary results from the EARLY ALLIANCE prevention trial. Am J Prevent Med. 2001;20:38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis CI, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, Greene SM, Schaefer JK, Vonkorff M. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:S7–S15. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Mosen D, Mendoza G, Apter AJ, et al. The controller-to total asthma medication ration is associated with patient-centered as well as utilization outcomes. Chest. 2006;130:43–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R, Curtis LM, Khiani S, Moy J, Shalowitz MU, Sharp L, Durazo-Arvizu RA, et al. A community-based study of tobacco smoke exposure among inner-city children with asthma in Chicago. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarville M, Sohn MW, Oh E, Weiss K, Gupta R. Environmental tobacco smoke and asthma exacerbations and severity: the difference between measured and reported exposure. Arch Dis Childh. 2013;98:510–514. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAS Statistical Software Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawyer MG, Barnes J, Frost L, Jeffs D, Bowering K, Lynch J. Nurse perceptions of family home-visiting programmes in Australia and England. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:369–374. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Mohandes AAE, Katz KS, El-Khorazaty N, McNeely-Johnson D, Sharps PW, Jarrett MH, Rose A, et al. The effect of a parenting education program on the use of preventive pediatric health care services among low-income, minority mothers: a randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1324–1332. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Backer V, Bornemann M, Knudsen D, Ommen H. Scheduled asthma management in general practice generally improve asthma control in those who attend. Respiratory Medicine. 2012;106:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakefield M, Banham D, Martin J, Ruffin R, McCaul K, Badcock N. Restrictions on smoking at home and urinary cotinine levels among children with asthma. Am J Prevent Med. 2000;19:188–192. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Redd SC. Involuntary smoking and asthma severity in children. Chest. 2002;122:409–415. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarlo SM. Workplace irritant exposures: do they produce true occupational asthma? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butz AM, Breysse P, Rand C, Curtin-Brosnan J, Eggleston P, Diette GB, Williams D, et al. Household smoking behavior: effects on indoor air quality and health of urban children with asthma. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:460–468. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0606-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ducharme FM, Zemek RL, Chalut D, McGillivray D, Noya FJ, Resendes S, Khomenko L, et al. Written action plan in pediatric emergency room improves asthma prescribing, adherence and control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:195–203. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0115OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKenzie DA, Semradek J, McFarland BH, Mullooly JP, McCamant LE. The validity of Medicaid pharmacy claims for estimating drug use among elderly nursing home residents: the Oregon experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1248–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]