Abstract

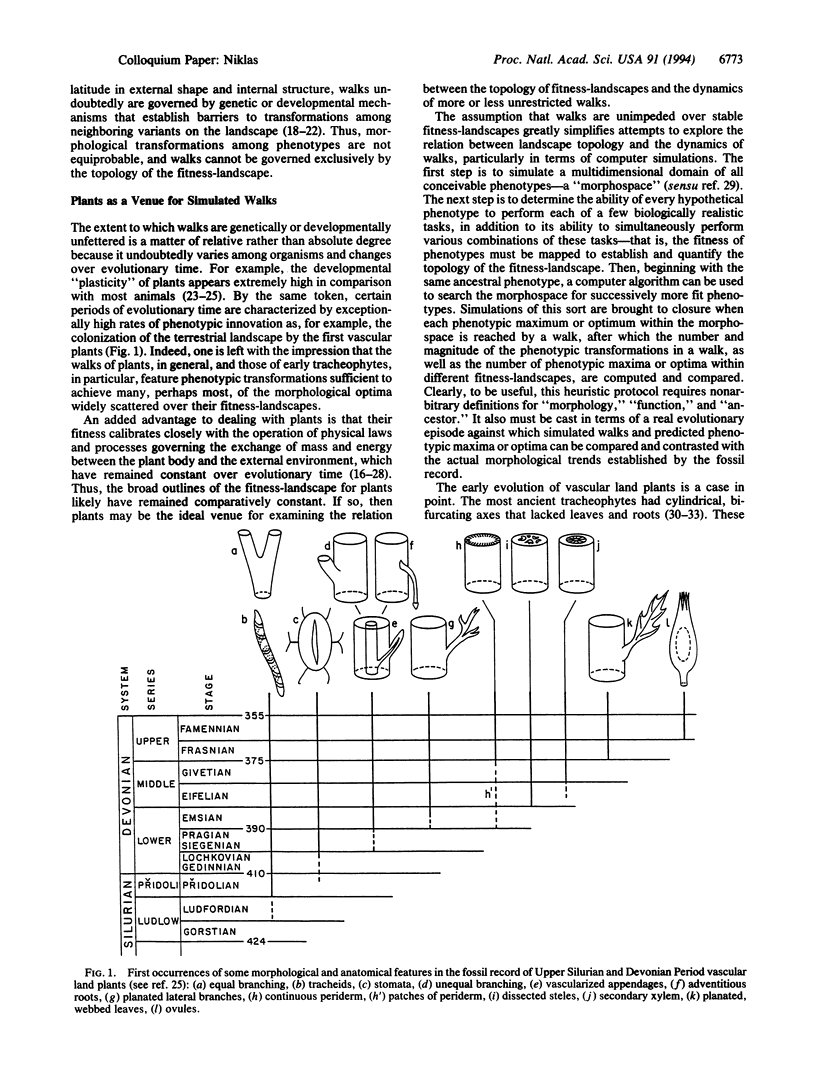

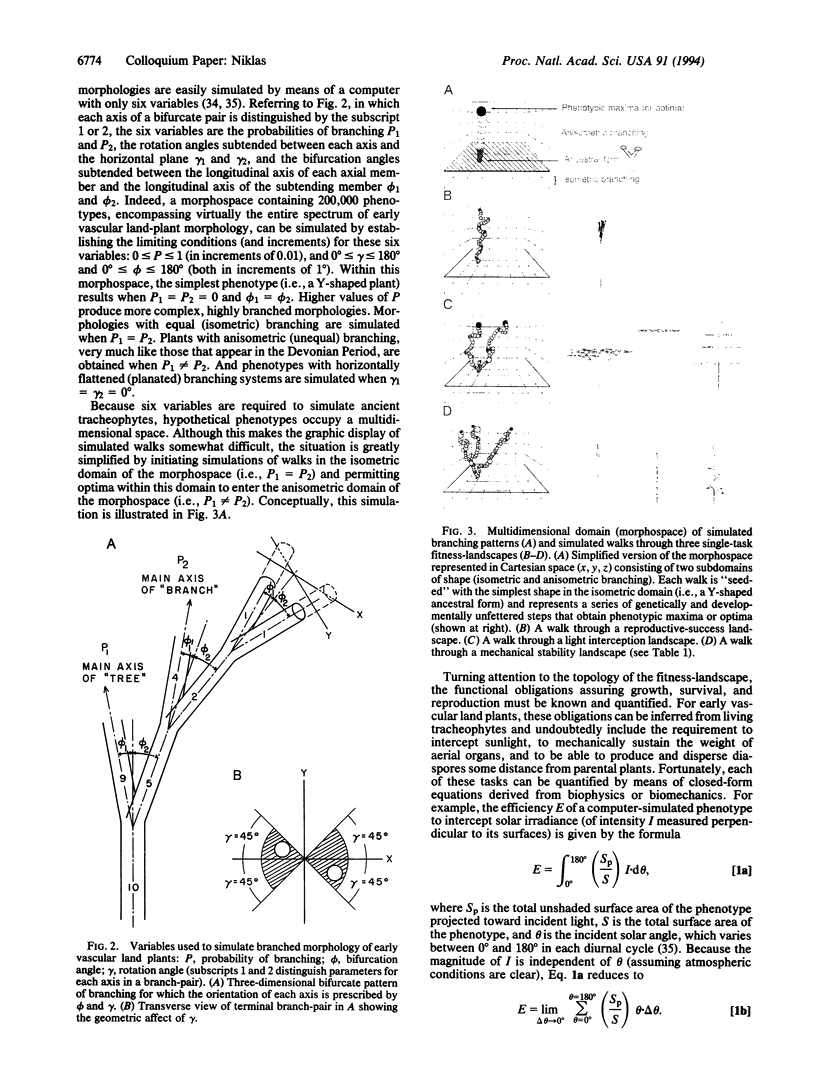

Computer simulated phenotypic walks through multi-dimensional fitness-landscapes indicate that (i) the number of phenotypes capable of reconciling conflicting morphological requirements increases in proportion to the number of manifold functional obligations an organism must perform to grow, survive, and reproduce, and (ii) walks over multi-task fitness-landscapes require fewer but larger phenotypic transformations than those through single-task landscapes. These results were determined by (i) simulating a "morphospace" containing 200,000 phenotypes reminiscent of early Paleozoic vascular sporophytes, (ii) evaluating the capacity of each morphology to perform each of three tasks (light interception, mechanical support, and reproduction) as well as the ability to reconcile the conflicting morphological requirements for the four combinatorial permutations of these tasks, (iii) simulating the walks obtaining all phenotypic maxima or optima within the seven "fitness-landscapes," and (iv) computing the mean morphological variation attending these walks. The results of these simulations, whose credibility is discussed in the context of early vascular land-plant evolution, suggest that both the number and the accessibility of phenotypic optima increase as the number of functional obligations contributing to total fitness increases (i.e., as the complexity of optimal phenotypes increases, the fitnesses of optima fall closer to the mean fitness of all the phenotypes under selection).

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Eigen M. New concepts for dealing with the evolution of nucleic acids. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:307–320. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin I., Lewontin R. C. Is the gene the unit of selection? Genetics. 1970 Aug;65(4):707–734. doi: 10.1093/genetics/65.4.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. H. A simple stochastic gene substitution model. Theor Popul Biol. 1983 Apr;23(2):202–215. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(83)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman S., Levin S. Towards a general theory of adaptive walks on rugged landscapes. J Theor Biol. 1987 Sep 7;128(1):11–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(87)80029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell G. M., Oster G., Alberch P., Burnside B. The mechanical basis of morphogenesis. I. Epithelial folding and invagination. Dev Biol. 1981 Jul 30;85(2):446–462. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics. 1931 Mar;16(2):97–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/16.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]