Summary

Cell division in Escherichia coli begins with assembly of the tubulin-like FtsZ protein into a ring structure just underneath the cell membrane. Spatial control over Z ring assembly is achieved by two partially redundant negative regulatory systems, the Min system and nucleoid occlusion (NO), which cooperate to position the division site at midcell. In contrast to the well-studied Min system, almost nothing is known about how Z ring assembly is blocked in the vicinity of nucleoids to effect NO. Reasoning that Min function might become essential in cells impaired for NO, we screened for mutations synthetically lethal with a defective Min system (slm mutants). By using this approach, we identified SlmA (Ttk) as the first NO factor in E. coli. Our combined genetic, cytological, and bio-chemical results suggest that SlmA is a DNA-associated division inhibitor that is directly involved in preventing Z ring assembly on portions of the membrane surrounding the nucleoid.

Introduction

Cell constriction (cytokinesis) in bacteria is carried out by the septal ring (Errington et al., 2003). Assembly of this multicomponent structure initiates with the polymerization of the tubulin-like FtsZ protein into a circumferential ring just underneath the cell membrane (Bi and Lutkenhaus, 1991). Formation of this Z ring in Escherichia coli requires at least one of the essential FtsZ binding proteins (ZBPs): FtsA or ZipA. Along with a nonessential ZBP (ZapA), these likely form part of the Z ring structure at the earliest stages of its assembly (Gueiros-Filho and Losick, 2002; Hale and de Boer, 1999; Pichoff and Lutkenhaus, 2002). The FtsZ-ZBP complexes that make up the Z ring recruit additional septal ring components, resulting in the assembly of a mature division machine capable of driving the coordinate invagination of the cell envelope layers (Aarsman et al., 2005; Goehring et al., 2005).

Spatial control over FtsZ assembly is achieved by two partially redundant inhibitory systems, Min and NO (nucleoid occlusion), which cooperate in the proper positioning of the FtsZ/septal ring at midcell (Errington et al., 2003; Yu and Margolin, 1999). In E. coli, the Min system is composed of the MinC, MinD, and MinE proteins encoded by the minB operon (de Boer et al., 1989). The system has been extensively characterized and essentially functions through a rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of the FtsZ-assembly antagonist MinC in a process that is driven by a set of interactions among the Min proteins, ATP, and membrane phospholipids (Hu et al., 2002; Hu and Lutkenhaus, 2001; Hu et al., 2003; Lackner et al., 2003; Raskin and de Boer, 1999; Shih et al., 2003). Oscillation of MinC causes its time-averaged concentration at the membrane to be highest at the cell poles and lowest at the cell center. This concentration differential of the division inhibitor is proposed to guide Z ring formation toward a narrow permissible zone around midcell (Hale et al., 2001; Meinhardt and de Boer, 2001). Loss of the Min system is not lethal but leads to frequent polar divisions, yielding chromosomeless minicells in addition to both normally sized and mildly filamentous cells (de Boer et al., 1989).

In contrast to Min, the mechanism responsible for the negative influence of the nucleoid on Z ring formation, NO, has long remained mysterious (Harry, 2001; Margolin, 2001). During the course of this study, a break through was reported by Wu and Errington (2004), who identified the first NO factor (Noc) in the Gram(+) bacterium Bacillus subtilis upon noticing that combinations of min mutations with deletions covering the yyaA (noc) gene in the soj-spoOJ region were lethal. Noc is a member of the ParB family of DNA binding proteins and was found distributed on the nucleoid in vivo. In the absence of a functional Min system, loss of Noc resulted in division inhibition and the aberrant formation of Z ring structures over nucleoids. In addition, Noc− cells failed to prevent the formation of septa over nucleoids when DNA replication was blocked, and Noc overproduction resulted in mild division inhibition. These results established Noc as a nucleoid-associated division modulator that, directly or indirectly, mediates NO in B. subtilis (Wu and Errington, 2004).

We took a direct genetic approach to uncover NO factors in the Gram(−) rod E. coli. Reasoning that an NO defect might be lethal in the absence of Min, we screened for mutations synthetically lethal with a defective Min system (slm mutants). Two such mutations mapped to slmA (ttk), a gene of unknown function that is predicted to encode a member of the TetR family of DNA binding proteins. Our results show that, similar to B. subtilis Noc, SlmA is a nucleoid-associated division inhibitor capable of mediating NO. Moreover, the in vivo and in vitro properties of SlmA strongly indicate that it promotes NO through a direct interaction with FtsZ.

Results

Isolation of slm Mutants

Recently, we described a generally applicable screening method for synthetic lethality in E. coli. Wishing to identify additional factors involved in FtsZ/septal ring assembly and its regulation, we applied the method to screen for mutants synthetically lethal with a defective Min system (slm mutants) (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004). The screen is modeled after the classic Saccharomyces cerevisiae synthetic lethal screen (Bender and Pringle, 1991) and relies on a colony-sectoring phenotype to identify mutants that retain a normally unstable mini-F plasmid (pTB8) containing the minCDE operon and lacZ under control of the lac promoter (Plac). Because the Min system is not essential, a ΔminCDE ΔlacIZYA strain readily loses pTB8 and forms either sectored-blue or solid-white colonies on nonselective LB agar containing IPTG and X-gal (LB-IX agar). Mutants with a Slm phenotype form colonies with a contrasting solid-blue appearance and are therefore readily identifiable.

For this study, strain TB43/pTB8 [ΔlacIZYA ΔminCDE/bla lacIq Plac::minCDE::lacZ] was mutagenized with EZTnKan-2 (Epicentre), yielding a library of about 2 × 105 independent transposon-insertion mutants. ~80,000 colonies were screened for rare mutants forming solid-blue colonies on LB-IX agar at 25 or 30°C. A total of 21 mutants were isolated. The majority of these displayed a slow growth phenotype in the absence of Min that varied from mild to severe. Slm127 and Slm267 were of particular interest, because they strictly required minCDE expression for colony formation. When grown in LB medium containing IPTG (Min+), Slm127 and Slm267 cells appeared normal (Figures 1A and 1C and data not shown). In the absence of IPTG (Min−), however, they formed long, mostly nonseptate filaments (Figures 1B and 1D and data not shown). Thus, septation itself, rather than just proper septal placement, had become dependent on a functional Min system in these mutants.

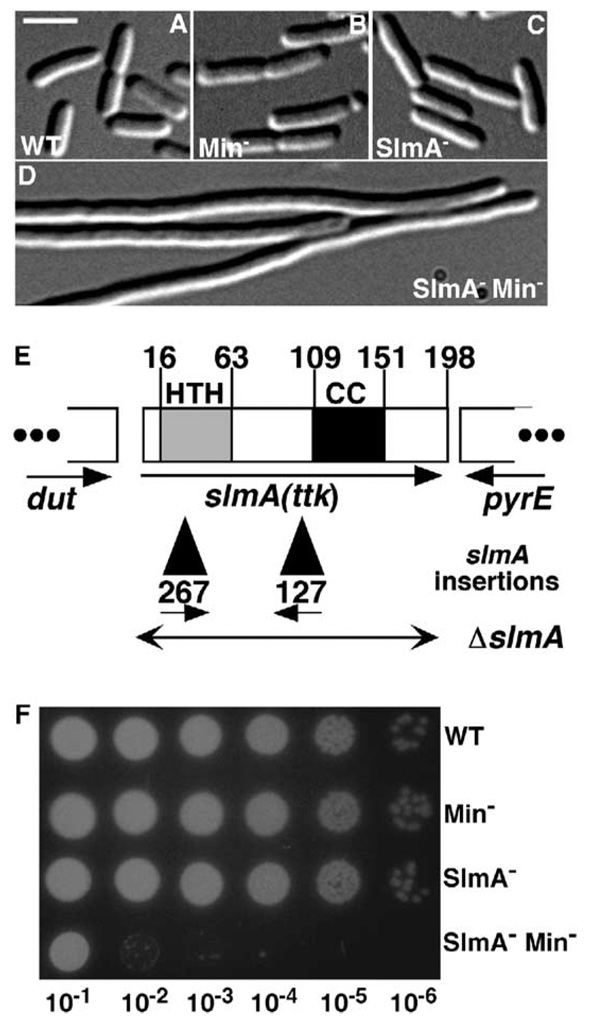

Figure 1. The slmA (ttk) Locus and Phenotypes of slmA Mutants.

(A–D) DIC micrographs showing cells of TB43/pTB8 [ΔlaclZYA::frtΔminCDE::frt/Plao::minCDE::JacZ] (A and B) and its slmA127 derivative (C and D). Cells were grown to OD600 = 0.6–0.7 in liquid LB-Amp with (A and C) or without (B and D) 500 µM IPTG and fixed. Bar = 5 µm.

(E) Diagram of the slmA locus indicating the location and orientation of the slmA127 and slmA267 EZTnKan-2 insertions (black triangles, inserted after bp 313 or 88 of slmA, respectively). SwissProt annotation P06969 was used to number amino acid residues. Potential DNA binding (HTH) and coiled-coil (CC) regions are indicated. The latter was identified by using COILS (Lupas et al., 1991). The double-headed arrow indicates the endpoints of the ΔslmA::aph and ΔslmA::frt deletion-replacement alleles.

(F) Overnight cultures of TB28 [wt], TB57 [Para::minCDE], TB66 [slmA127], and TB68 [slmA127 Para::minCDE] were grown to equal density in LB-0.2% arabinose and serially diluted (10−1-10–6) in LB. Aliquots (5 µl) were spotted on LB agar without arabinose and incubated overnight at 30°C.

Identification and Genetic Analyses of slmA

The EZTnKan-2 insertions of Slm127 and Slm267 both mapped to the poorly characterized ttk gene. Until now, no phenotype had been associated with ttk, which was so named because it encodes a twenty-three-kDa protein (el-Hajj et al., 1988) (B. Weiss, personal communication). Based on its newly discovered phenotype, we renamed the gene slmA. Sequence analysis indicates that the SlmA protein contains an N-terminal, TetR-like helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (Bateman et al., 2002) and a C-terminal region predicted to form a coiled coil (Figure 1E).

To facilitate further study of the SlmA− Min− phenotype, we constructed strains containing either the slmA127 transposon insertion or a complete slmA deletion replacement (ΔslmA::aph) (Figure 1E) in combination with a min allele in which the chromosomal operon is placed under control of the araBAD promoter (Para::minCDE). These strains were arabinose dependent for growth and displayed a plating defect of three to four orders of magnitude on LB agar lacking the sugar (Figure 1F and data not shown). As with the original Slm isolates (Figure 1D), this poor growth in the absence of minCDE expression correlated with a severe filamentation phenotype (see below).

We identified two conditions that suppressed the SlmA− Min− growth and division defects: mild (2- to 3-fold) overexpression of ftsZ in cells harboring either pTB63 [ftsQAZ] or pDR3 [Plac::ftsZ] (in the presence of 10 µM IPTG) and growth on M9 minimal medium (Figure 2F and data not shown). The latter allowed us to construct strain TB86 [ΔminCDE::frt ΔslmA::aph], which grew well on M9 medium but showed the lethal SlmA− Min− division defect on LB. A detailed understanding of the medium dependence of the phenotype will require further exploration. As FtsZ levels reportedly increase significantly with slower growth rates (Aldea et al., 1990), we considered that the medium-dependent suppression of filamentation might be directly related to that mediated by ftsZ overexpression. In agreement with a more recent study (Weart and Levin, 2003), however, immunoblotting revealed that relative FtsZ levels were essentially unchanged in cells grown in M9 medium compared to LB (data not shown).

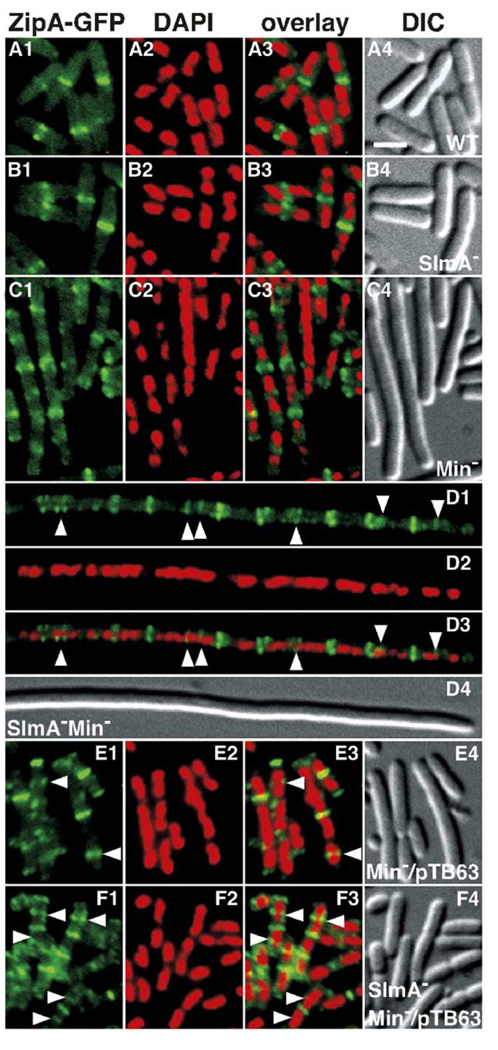

Figure 2. Septal Ring and Nucleoid Positioning in SlmA− and SlmA− Min− Mutants.

Shown are representative cells of the following λCH151 [Plac::zipA-gfp] lysogens: TB28 [wt] (A), TB85 [ΔslmA::aph] (B), TB43 [ΔminCDE::frt] (C), TB86 [ΔslmA::aph ΔminCDE::frt] (D), TB43/pTB63 (E), and TB86/pTB63 (F). Plasmid pTB63 [ftsQAZ] is a low-copy, pSC101-derivative expressing ftsQAZ from native promoters. Cells were grown to OD600 = 0.6–0.7 at 30°C in LB with 37 µM IPTG, fixed, stained with DAPI (0.25 µg/ml), and imaged with optics specific for GFP (A1, B1, C1, D1, E1, and F1), DAPI (A2, B2, C2, D2, E2, and F2), and DIC (A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, and F4). A3, B3, C3, D3, E3, and F3 show a digital overlay of the GFP and DAPI signals. Arrowheads point to examples of ZipA-GFP rings, and other types of accumulations, in regions with significant DAPI staining. Bar = 2 µm.

The SlmA− Min− division defect of TB86 [ΔminCDE::frt ΔslmA::aph] was corrected by slmA expression from pTB70 [Plac::slmA], showing that the phenotype was indeed due to the loss of slmA and not to polar effects on nearby genes (data not shown). SOS-induced division inhibition did not cause the SlmA− Min− division phenotype, as the RecA− strain TB84 [slmA127 Para::minCDE recA::Tn10] also failed to divide in the absence of arabinose (data not shown). In addition, quantitative immunoblotting of extracts from appropriate strains showed that FtsZ levels were neither affected by the absence nor by overexpression of SlmA, regardless of the Min status of cells (data not shown). Thus, even though the division block in SlmA− Min− cells could be suppressed by overexpression of ftsZ, the block did not result from reduced FtsZ levels.

Aberrant Septal Ring Assembly in SlmA− Min− Cells

To better understand the division defect in SlmA− Min− cells, we compared FtsZ/septal ring and nucleoid distribution patterns in TB28 [wt], TB85 [ΔslmA::aph], TB43 [ΔminCDE::frt], and TB86 [ΔminCDE::frt ΔslmA::aph] cells containing the prophage λCH151 [Plac::zipA-gfp]. Cells were grown to an OD600 of about 0.6 at 30°C in LB medium containing 37 µM IPTG. They were then fixed, stained with DAPI, and viewed by fluorescence and DIC microscopy. For each strain, cell length, the number of FtsZ structures present per cell, and the number of these structures observed over nucleoids were measured (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Data available with this article online). Representative micrographs are presented in Figure 2. Similar results were obtained when, instead of ZipA-GFP, a GFP-FtsZ fusion was used as a probe for FtsZ assemblies in cells (Figure S1).

As expected, the majority of wild-type (wt) cells showed a single ZipA-GFP ring at midcell situated in a gap between two segregated nucleoids (Figure 2A). In about one-fifth (35/196) of these cells, nucleoid segregation had not yet been completed, and the ring encircled a bridge of material still connecting the sister nucleoids. This result is consistent with previous work implying that NO is relieved in the gap between nucleoids prior to completion of segregation (den Blaauwen et al., 1999; Lau et al., 2003; Li et al., 2003). SlmA− cells were essentially indistinguishable from wt cells (Figure 2B and Table S1), indicating that the loss of SlmA by itself did not grossly affect nucleoid compaction/segregation or septal ring formation.

Consistent with previous results (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004; Yu and Margolin, 1999), Min− cells contained about twice as many structures per unit length as wt (Table S1), with a ring, or sometimes a double ring or spiral, of markedly variable intensity at almost every nucleoid-free region (Figure 2C). The increase in the density of Z structures was not accompanied by a significant increase in the fraction of structures located over nucleoids (76/341, ~22%). Interestingly, the SlmA− Min− filaments had an even greater density of Z structures, about 40% more per unit length than the Min− cells, with many taking the form of atypical spiral-, arc-, and focal-like accumulations as opposed to canonical rings. Moreover, the majority (~85%) of these aberrant additional structures were located over nucleoids (Figure 2D and Table S1). Compared to the Min− cells, this represented about a 2.5-fold increase in the number of Z structures observed over nucleoids per unit length (Table S1). Overall, these results indicate that the division defect of SlmA− Min− cells is not due to an in-ability to initiate Z ring assembly but rather to a topologically unrestrained formation of too many assemblies at the same time. Competition for components may then prevent any of these from maturing to a constriction competent organelle (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004; Yu and Margolin, 2000).

The fact that an extra supply of FtsZ completely alleviated the division block of SlmA− Min− cells (Figure 2F and data not shown) is consistent with this idea. These suppressed cells also formed septal ring structures over nucleoids. In fact, this defect was even more apparent than in the unsuppressed cells (compare Figures 2E and 2F; Table S1). Aberrant ZipA-GFP structures over nucleoids were also observed in SlmA− Min− cells when filamentation was suppressed by growth in M9 medium (data not shown).

It is notable that under either condition of filamentation suppression, the SlmA− Min− cells grew about as well as wt cells and did not appear to divide over and “cut” chromosomes at a significant frequency (Figure 2F and data not shown). Perhaps FtsZ assemblies that formed over the nucleoids in these cells specifically failed to mature into functional rings, or their function was somehow delayed until the underlying nucleoid was cleared away.

SlmA Is Required for the Antiguillotine Checkpoint

The results above established that SlmA− Min− cells are defective in preventing ZipA-GFP structures from forming near nucleoids, indicating that SlmA is required for NO. To test this idea further, we studied the possible involvement of SlmA in a checkpoint that normally prevents chromosomal cutting by blocking midcell septum formation when the nucleoid(s) fails to clear this site (Hirota et al., 1968). This antiguillotine checkpoint is one of the clearest manifestations of NO (Hussain et al., 1987; Mulder and Woldringh, 1989; Yu and Margolin, 1999), and it has been equally poorly understood.

Checkpoint integrity was compared in the Min+ strains TB104 [cI857 λPR::dnaA] and TB105 [ΔslmA::frt cI857 λPR::dnaA]. The chromosomal dnaA allele of these strains is controlled by the phage λ PR promoter and a temperature-sensitive mutant of λ repressor such that production of the initiator of chromosome replication is temperature dependent. Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.2, diluted 4-fold, and shifted to 30°C to repress dnaA expression. After 3.5 hr, the cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and viewed by fluorescence and DIC microscopy. The vast majority (108/110) of TB104 (SlmA+) cells were elongated and contained a single nucleoid mass centered about mid-cell (class a) (Figures 3A and 3D). As expected, septa did not form over the central nucleoid in these cells, indicating the checkpoint was intact.

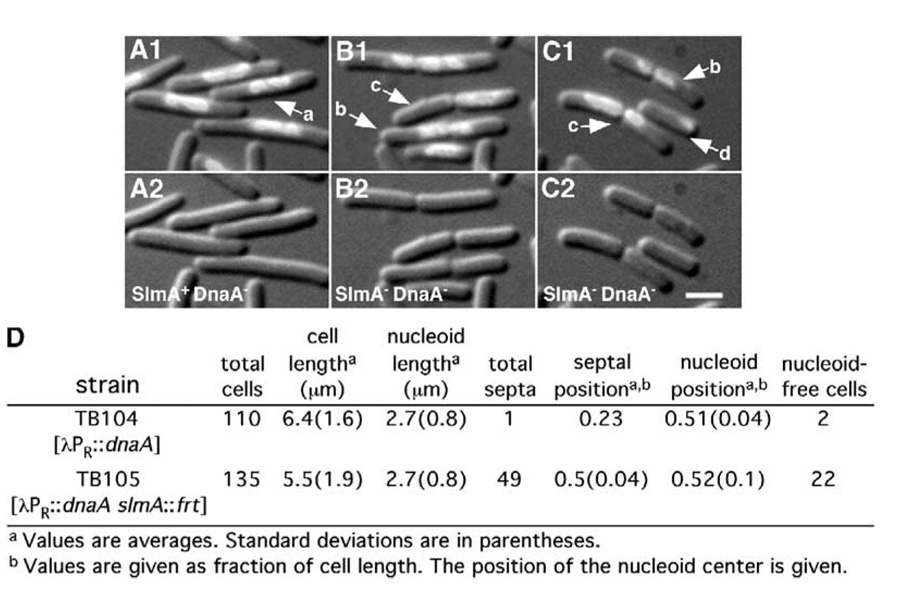

Figure 3. Nucleoid Cutting in SlmA− DnaA− Cells.

Cells of TB104 [cI857 λPR::dnaA] (A) and TB105 [ΔslmA::frt cI857 λPR::dnaA] (B and C) were grown in LB for 3.5 hr at 30°C to deplete DnaA. Cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and imaged with DAPI- and DIC-specific optics. A1, B1, and C1 show a digital overlay of the DIC and DAPI images, and A2, B2, and C2 show the DIC image only. Bar = 2 µm. Several parameters of randomly selected cells from each strain were measured, and the results are summarized in (D).

The results were strikingly different for TB105 (SlmA−) cells. The majority also contained a single nucleoid mass centered about midcell (Figures 3B–3D). However, a significant number (49/135) showed a midcell septum forming directly over the nucleoid. In about half of these cells, the septum appeared to bisect the nucleoid (class b, 21/49), whereas in the others, the nucleoid was distributed asymmetrically (class c, 28/49) as if it had moved through the septal pore (Figures 3B–3D). Some cells apparently completed division over the nucleoid, guillotining the chromosome to produce cells with a small amount of polar DAPI staining (class d, 5/135). A significant number (22/135) of nucleoid-free cells were also observed. These may either have resulted from cells of class c that managed to completely transfer the nucleoid through the septal pore to one of the daughter cells or from cells of class d that contained damaged chromosomes that were degraded.

These results show that SlmA is required for the antiguillotine checkpoint in DnaA− cells and strongly support the proposal that SlmA− cells are defective in NO.

Distribution of GFP-SlmA on the Nucleoid

The presence of a TetR-like HTH domain in SlmA (Figure 1E) suggested it might bind DNA and localize to the nucleoid. To test this, we placed a gfp-slmA fusion under control of the lac promoter and integrated it in single copy at the chromosomal attachment site for phage HK022. The GFP-SlmA fusion protein was functional, as growth of the SlmA− Min− strain TB86(HKTB99) [ΔminCDE::frt ΔslmA::aph (Plac::gfp-slmA)] on LB medium was strictly dependent on the presence of IPTG, and full suppression of its SlmA− Min− division phenotype was attained at 250 µM of the inducer (data not shown).

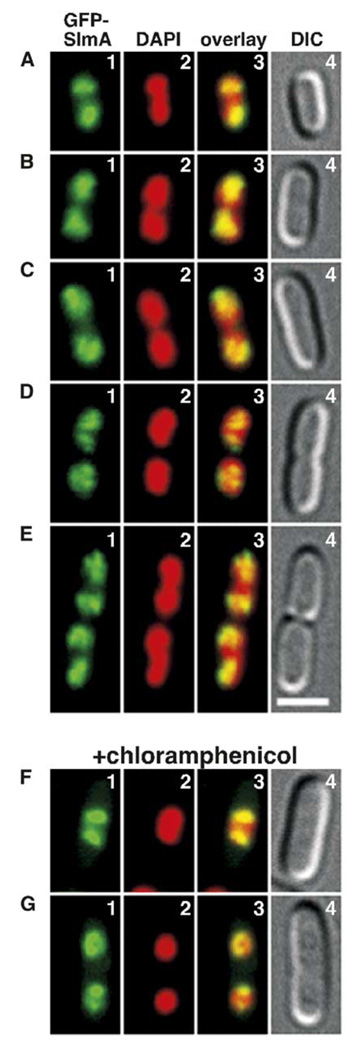

Cells of the corresponding SlmA− Min+ strain TB85 (HKTB99) [ΔslmA::aph (Plac::gfp-slmA)] were grown in LB with 250 µM IPTG, and the distributions of GFP-SlmA and DAPI-stained nucleoids were examined by microscopy of live cells. The GFP signal was weak and photobleached rapidly. Nevertheless, GFP-SlmA was clearly associated with the nucleoid(s) in all cells. Figures 4A–4E illustrate changes in GFP-SlmA distribution as a function of the cell cycle. Most newborn cells contained a single nucleoid mass on which the majority of the GFP-SlmA signal appeared segregated to both pole-proximal regions (Figure 4A). In older cells with distinctly bilobed or newly separated nucleoids (Figures 4B–4D), the GFP-SlmA signal appeared more spread out over the nucleoid(s). Finally, in cells that had completed nucleoid segregation and were about to divide, GFP-SlmA once again appeared segregated to the pole-proximal portions of the daughter cell nucleoids (Figure 4E). Confirming its affinity for the nucleoid, GFP-SlmA cocondensed with the nucleoid upon brief treatment of cells with chloramphenicol. Moreover, the fusion seemed to retain its preference for pole-proximal portions of nucleoids in many of these cells (Figures 4F and 4G).

Figure 4. Distribution of GFP-SlmA on the Nucleoid.

Shown are live cells of TB85(HKTB99) [ΔslmA::frt (Plac::gfp-slmA)] grown to OD600 = 0.5–0.6 at 30°C in LB with 250 µM IPTG. DAPI was added to 0.25 µg/ml 30 min prior to imaging. Cells in (F) and (G) were treated with chloramphenicol (100 µg/ml) and grown for an additional 30 min prior to viewing. Panels show GFP-SlmA (1), DAPI (2), merged (3), and DIC (4) images. Bar = 2 µm.

Apart from the apparent preference for pole-proximal portions of the nucleoid(s) in many of the cells, the GFP-SlmA signal often appeared partially concentrated in (combinations of) multiple dots, arcs, rings, or spiral forms (e.g., Figures 4C–4E and data not shown). Whether these simply reflect contours of the nucleoid, the specific binding of GFP-SlmA to multiple sites, or some other special architecture is not clear.

To determine if the HTH domain of SlmA is required for its nucleoid association, we examined the localization of a GFP fusion lacking this domain [GFP-SlmA(65–198)]. Production of the truncated fusion from pTB73 [Plac::gfp-slmA(65–198)] resulted in a uniform cytoplasmic fluorescence signal in TB28 [wt], and failed to correct the division defect of TB86 [ΔminCDE::frt ΔslmA::aph] (data not shown). Immunoblotting indicated that the cytoplasmic signal and corresponding loss of function were not the result of excessive proteolysis of GFP-SlmA(65–198). We conclude that the HTH domain of SlmA is required for both its association with the nucleoid and its ability to mediate NO.

SlmA-Mediated Division Inhibition and Recruitment of FtsZ to the Nucleoid

The results above showed that SlmA is a nucleoid-associated protein that is required for NO. An attractive possibility, also proposed for Noc (Wu and Errington, 2004), is that SlmA is a division inhibitor capable of mediating NO directly. Quantitative immunoblotting revealed that an average wt cell contains 300–400 copies of SlmA, which is comparable to the concentration of the division inhibitor MinC (data not shown) (Szeto et al., 2001). Consistent with the idea that SlmA acts as a division inhibitor was the observation that its overproduction by about 50-fold from plasmid pTB67 (Ptac::slmA) caused a complete division block in TB28 [wt] (Figure 5B and data not shown). This was not due to SOS- or MinC-mediated division inhibition, because TB49 [recA::Tn10] and TB43 [ΔminCDE::frt] cells were also sensitive to SlmA-induced filamentation (data not shown). As controls, we also studied three other E. coli TetR-like proteins that are of comparable size and/or charge as SlmA (22.8 kDa, pI = 8.8). Even when massively overproduced, however, AcrR (24.8 kDa, pI = 5.7), BetI (21.8 kDa, pI = 10.2), and YcdC (23.7 kDa, pI = 8.9) failed to block cell constriction, showing that division inhibition is not a general outcome of overproduction of this class of proteins (data not shown).

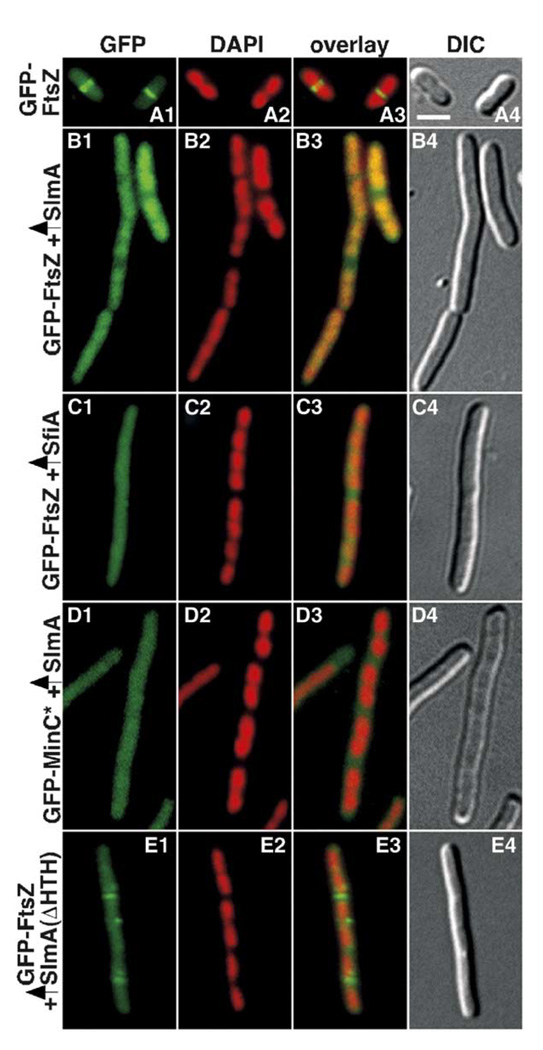

Figure 5. slmA Overexpression Blocks Z Ring Formation.

Shown are cells of strain TB28/pDB407 [wt/λPR::gfp-ftsZ] harboring pJF118EH [vector] (A), pTB67 [Ptac::slmA] (B), pDR144 [Plac::sfiA] (C), or pTB108 [Ptac::slmA(58–198)-h] (E). D1–D4 show a cell of strain TB28/pLL14/pTB67 [wt/λPR::gfp-minC(141–231)/Ptac::slmA]. Cells were grown to OD600 = 0.25–0.3 at 39°C in LB-Amp-Spc. DAPI (to 0.25 µg/ml) and IPTG (to 50 µM) were added, and growth was continued for 30 min prior to imaging. Cells were imaged live, and panels show GFP (1), DAPI (2), merged (3), and DIC (4) images. Bar = 2 µm. Note that continued incubation of the cells in panels B1–E4 led to the formation of very long nonseptate filaments, indicative of a complete division block.

To determine the effect of slmA overexpression on Z ring formation, GFP-FtsZ was expressed from pDB407 [λPR::gfp-ftsZ], and cells were examined shortly after SlmA overproduction was initiated. Surprisingly, not only was Z ring formation blocked but also a significant portion of GFP-FtsZ actually accumulated on the nucleoids (Figure 5B). Accumulation of FtsZ on the nucleoid has not been previously observed under any other circumstance (Addinall et al., 1996; Ma et al., 1996; Romberg and Levin, 2003). For example, GFP-FtsZ appears uniformly cytoplasmic when Z ring formation is blocked by the SOS-regulated division inhibitor SfiA (SulA) (Figure 5C) (Mukherjee et al., 1998). SlmA-induced nucleoid recruitment of GFP-FtsZ was specific for the FtsZ portion of the fusion as a normally cytoplasmic GFP-MinC(141–231) fusion (Johnson et al., 2002) remained cytoplasmic upon SlmA overproduction (Figure 5D).

Overproduction of SlmA(58–198)-H, a truncated version that lacks the HTH motif, also induced filamentation and did so whether or not native SlmA was present in the cells (Figure 5E and data not shown). A few partial GFP-FtsZ assemblies often remained in these filaments, but most of the signal appeared cytoplasmic without any noticeable preference for nucleoids (Figure 5E). These results indicate that neither SlmA nor FtsZ need to accumulate on the nucleoid in order for SlmA-induced filamentation to occur.

SlmA and FtsZ Interact In Vitro

The recruitment of GFP-FtsZ to the nucleoid upon SlmA overproduction suggested that the two proteins might interact directly. For in vitro experiments, we purified His6-T7.tag-SlmA (HT-SlmA). This tagged version of SlmA was functional in vivo as judged by the ability of plasmid pTB82 [Plac::ht-slmA] to correct the division phenotype of TB86 [Δ minCDEr.frt Δ slmA::aph] (data not shown). AcrR, BetI, and YcdC were similarly tagged and purified to serve as control reagents. Purified HT-BetI was poorly soluble and not useful in subsequent assays, but the other proteins behaved well.

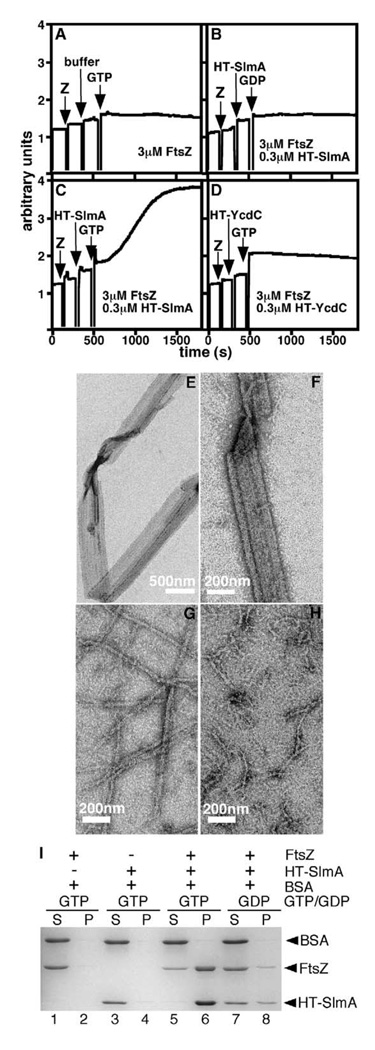

We used a light-scattering assay to determine if HT-SlmA affected FtsZ polymerization. Reaction parameters (3 µM FtsZ at pH 7.2) were chosen to be physiologically relevant rather than optimal for polymer formation (Mukherjee and Lutkenhaus, 1999). Addition of GTP to reactions containing FtsZ alone led to the formation of short polymers. These ranged in width from 5–15 nm, corresponding to single protofilaments and complexes of two to four laterally-associated ones (Figure 6H). Formation of these structures caused a negligible increase in light scattering (Figure 6A). When HT-SlmA (0.3 µM) was included in the reaction, however, the addition of GTP led to a striking increase in scatter, suggesting the formation of much larger structures (Figure 6C). Electron microscopy revealed that HT-SlmA caused FtsZ protofilaments to arrange into long, ribbon-like assemblies about 200–500 nm wide, which increased in size with increasing SlmA:FtsZ ratios (Figures 6E and 6F and data not shown). Control reactions showed that ribbon formation required the presence of FtsZ, HT-SlmA, and GTP, regardless of the SlmA:FtsZ ratio (Figures 6B and 6H and data not shown). When GTP was replaced with GDP, only some clusters of amorphous material were seen (data not shown). Analysis of sedi-mented ribbons confirmed that they contained both FtsZ and HT-SlmA (Figure 6I).

Figure 6. Formation of FtsZ-SlmA Ribbons.

(A–D) 90° angle light scattering was monitored in reactions containing 3 µM FtsZ before and after the addition of HT-SlmA storage buffer and GTP (1 mM) (A), HT-SlmA (0.3 µM) and GDP (1 mM) (B), HT-SlmA (0.3 µM) and GTP (1 mM) (C), and HT-YcdC (0.3 µM) and GTP (1 mM) (D).

(E–H) Electron micrographs of structures formed in reactions containing 3 µM FtsZ and 1 mM GTP with the addition of 0.6 µM HT-SlmA (E and F), 0.6 µM HT-YcdC (G), or HT-SlmA storage buffer (H). Bar = 500 nm (E) or 200 nm (F–H).

(I)SDS-PAGE analysis of supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions after centrifugation of reactions containing nucleotide (1 mM) and proteins (6 µM each) as indicated. Note that the pellet fractions were twice as concentrated as the supernatant fractions (see Experimental Procedures).

In contrast to HT-SlmA, the presence of HT-AcrR had no measurable effect on FtsZ polymer assembly (data not shown), whereas that of HT-YcdC led to a small increase in light scatter (Figure 6D). This increase correlated with the presence of polymer bundles that were only a few times wider (20–40 nM) than those seen in the absence of HT-YcdC. Because FtsZ is acidic (pI = 4.7) and HT-YcdC basic (pI = 9.3), the increased tendency of FtsZ polymers to bundle in the presence of HT-YcdC may result from a reduction in electrostatic repulsion between individual filaments due to nonspecific charge compensation (Tang and Janmey, 1996). This is also thought to explain how polyvalent cations like Ca2+, Mg2+, and DEAE-dextran promote bundling of FtsZ polymers (Mukherjee and Lutkenhaus, 1999).

Because HT-SlmA is equally basic (pI = 9.4), charge compensation may also contribute to its ability to stimulate the lateral alignment of FtsZ protofilaments. However, the efficiency by which HT-SlmA mediated polymer association was far greater than that of HT-YcdC and rather comparable to that of the known ZBPs, ZipA and ZapA, in inducing bundling of FtsZ polymers in vitro (Gueiros-Filho and Losick, 2002; Hale et al., 2000) (data not shown). Both this high efficiency and the markedly regular nature of the ribbon-like assemblies induced by HT-SlmA indicate that its interaction with FtsZ must be fairly specific.

Taken together with the genetic and cytological results presented above, these results indicate that SlmA is likely to effect NO via a direct interaction with FtsZ.

Discussion

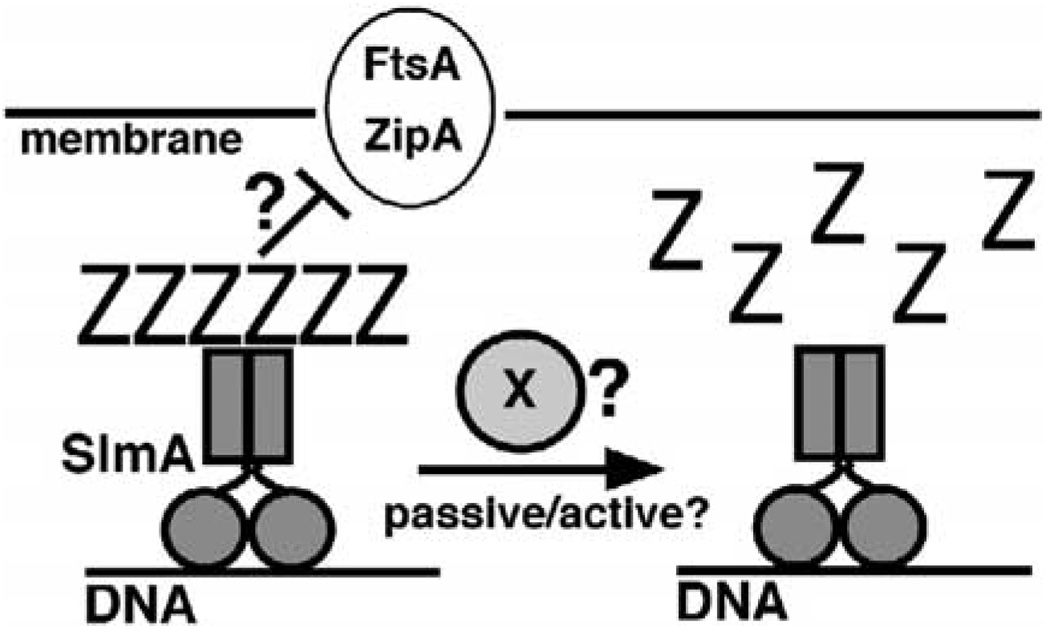

The nucleoid occlusion phenomenon in bacteria has long remained mysterious. Aiming to gain a molecular handle on the process, we searched for mutants synthetically lethal with a Min− phenotype and identified SlmA as the first factor required for NO in E. coli. We further showed that SlmA is a nucleoid-associated protein that can bind FtsZ (polymers) directly. The in vivo and in vitro properties of SlmA favor models in which the DNA bound protein mediates NO by directly interfering with Z ring formation in its vicinity (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Model for SlmA Function.

DNA bound SlmA, presumed to be a dimer, competes with membrane bound septal ring components, such as ZipA and FtsA, for binding FtsZ polymers. In subsequent steps, SlmA may play a rather passive role in that SlmA bound polymers may simply turn-over due to their intrinsic GTP hydrolytic activity. A more attractive possibility is that SlmA, perhaps in combination with some other factor (X), actively promotes the disassembly of the FtsZ polymers.

To block Z ring formation, nucleoid bound SlmA may compete with membrane-associated ZBPs, such as FtsA and ZipA, for binding to FtsZ polymers and thus prevent them from developing into an FtsZ ring. In the simplest scenario, SlmA merely acts as a nucleoid-associated sink for FtsZ polymers without reducing their stability. In fact, our observation that SlmA promotes the association of FtsZ protofilaments into ribbon-like assemblies in vitro suggests that SlmA may actually stabilize Z polymers on the nucleoid. Arguing against this, however, is that a substantial depository of FtsZ on the nucleoid is usually not evident by microscopy (Figure 5A) (Addinall et al., 1996; Ma et al., 1996). In an alternative scenario, SlmA actively promotes the depolymerization of FtsZ in vivo. This possibility is attractive as it is consistent with the absence of an obvious FtsZ depository on nucleoids and would seem a more efficient way of effecting NO. Despite some effort, we have not found conditions under which SlmA destabilizes FtsZ polymers in vitro, suggesting that SlmA may require partner molecules to do so in vivo. One obvious factor that might convert SlmA into an FtsZ-depolymerase is DNA. Addition of DNA from various sources had no effect on the formation of FtsZ-SlmA ribbons in our purified system (data not shown), but SlmA may require specific DNA sequences and/or to-pologies.

Although the observed SlmA-FtsZ interaction favors a direct role for SlmA in the mechanism of NO, indirect roles are difficult to exclude with certainty. For example, SlmA may be a transcription factor required for production of the actual NO factor(s), themselves presumably nucleoid bound modulators of FtsZ assembly. Alternatively, SlmA may have a more general function in nucleoid organization and/or packing, and its loss may secondarily affect NO. One argument against these possibilities is that overproduction of a cytoplasmic (ΔHTH) version of SlmA still interfered with Z ring assembly (Figure 5E), implying that DNA binding is not a prerequisite for SlmA to affect the process. In addition, it was recently shown that, although nucleoid density/compaction can affect NO, a severe degree of nucleoid decondensation is required to abolish it (Sun and Margolin, 2004). We did not notice any change in nucleoid structure in the absence of SlmA (Figure 2B), suggesting that an alteration of nucleoid structure is not at the heart of the SlmA− defect.

During the course of this study, Wu and Errington (2004) presented the discovery of B. subtilis Noc. Considering that (1) E. coli and B. subtilis are evolutionary far removed, (2) SlmA and Noc belong to completely different families of DNA binding proteins (TetR and ParB, respectively), and (3) the proteins lack any obvious primary sequence similarity, it is remarkable how similar the genetic and cytological properties of SlmA− and Noc− mutants are. In fact, although it is not yet known if Noc can bind FtsZ directly, the models for SlmA’s role in NO described above equally apply to Noc.

As expected for NO factors, SlmA and Noc both localize to the nucleoid in their respective organism. Interestingly, although they can be seen throughout the nucleoid, the highest concentration of both proteins often seems present at the pole-proximal regions as if they segregate prior to bulk nucleoid segregation. The significance of this apparent presegregation is presently unclear. As suggested for Noc (Wu and Errington, 2004), however, it may cause relief of NO at midcell, allowing for the initiation of Z ring assembly prior to the completion of nucleoid replication and segregation (den Blaauwen et al., 1999; Lau et al., 2003; Li et al., 2003).

Like Noc− Min− mutants, the NO defect of SlmA− Min− mutants appeared to be incomplete in that Z ring positioning still seemed biased toward internucleoid regions. Several nonexclusive explanations for this bias are possible. Some nonspecific property of the nucleoid, like steric crowding at the membrane, may continue to bias Z ring assembly away from it. Alternatively, the bias could be generated by additional specific Z ring inhibitors present on the nucleoids or by activators of Z ring assembly located between them. One additional consideration is that septal ring assemblies themselves may contribute significantly to the bias. At sites where FtsZ had assembled over nucleoids in SlmA− Min− filaments, we frequently noted corresponding local perturbations in nucleoid shape (Figure 2D), as if the assemblies attempted to “occlude” the underlying nucleoid. Even more striking was the apparent movement of the nucleoid through the central septal pore in many of the DnaA− SlmA− cells (Figure 3). Because septal ring assemblies contain the DNA translocase FtsK (Aussel et al., 2002), movement of the nucleoid relative to these assemblies is not necessarily unexpected (Lau et al., 2003). Therefore, it seems likely that the apparent preference of septal rings for nucleoid-free regions not only results from interference with Z ring assembly by nucleoid-associated factors such as SlmA (i.e., NO in the strictest sense) but also from the ability of septal rings to clear away underlying DNA.

As long as the Min system was operational, cells lacking SlmA did not have a detectable division phenotype (Figure 1C and Figure 2B). This is consistent with previous results indicating that Min is capable of directing Z rings to midcell even in cells lacking nucleoids altogether (NO−), although perhaps less accurately than in wt (NO+) cells (Sun et al., 1998; Yu and Margolin, 1999). In the absence of Min, SlmA became critical in preventing the coincident assembly of too many Z structures, which correlated with a complete division block on rich medium. These results suggest that, under normal conditions, Min is the dominant determinant of septal ring positioning, with NO playing a partially overlapping auxilliary role. In addition, however, both SlmA (Figure 3) and Noc (Wu and Errington, 2004) have now been shown to play a critical role in the antiguillotine checkpoint that prevents septa from forming over nucleoids when problems arise during replication or segregation. In species such as E. coli and B. subtilis that employ a Min system to position the septal ring, the execution of this checkpoint may be the most important function of NO. It is tempting to speculate, however, that in organisms that lack a Min system (Rothfield et al., 1999), proteins such as SlmA and Noc are primary factors in establishing the proper plane for FtsZ assembly.

Experimental Procedures

Strains, Plasmids, Phages, Media, and slm Screen

The source or construction and the genotype of each strain, plasmid, and phage are detailed in the Supplemental Data. Relevant genotypes [in brackets] are also provided in the text. All strains described in the text are derivatives of MG1655. Plasmids are derivatives of mini-F (pTB8), pSC101 (pDB407, pLL14, and pTB63), or colE1 (all others). The prophage λCH151 was described previously (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004).

Unless noted otherwise, cultures were grown in LB (1 % tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5%–1.0% NaCl) or minimal M9 media (Miller, 1972) supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids, 50 µM thiamine, and 0.2% sugar as indicated. Solid media included 1.5% Difco-agar. Where appropriate, the medium was supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations: tetracycline (Tet, 12.5 µg/ml), kanamycin (Kan, 20 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cam, 25 µg/ml), spectinomycin (Spc, 75 µg/ml), and ampicillin, (Amp, 50 µg/ml).

EZTnKan-2 (Epicentre) transposon mutagenesis of strain TB43/pTB8, the subsequent screen for slm mutants, and the mapping of insertions by arbitrary PCR were done as described previously (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004).

Microscopy

Light and electron microscopy (EM) were performed essentially as described (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004; Hale et al., 2000). For the micrographs shown in Figure 1A, Figure 4, and Figure 5, cultures were grown overnight at 30°C in LB, and for those in Figure 2, at 37°C in M9-glucose. The cultures were diluted 1:100 into fresh LB media and treated as described in the figure legends. Cultures for Figure 1A were supplemented with Amp and those for Figure 5 with both Amp and Spc.

For the DnaA depletion experiment, cultures of TB104 [cI857 λPR::dnaA] and TB105 [ΔslmA::frt cI857 λPR::dnaA] were grown overnight in LB at 37°C and diluted 1:100 into LB. The cultures were then treated as described in the text and the legend to Figure 3. Cell fixation was carried out as described previously (Bernhardt and de Boer, 2004). Object image 2.10 (Vischer et al., 1994) was used to measure the cellular parameters in Figure 3D and Table S1.

Reactions analyzed by EM were identical to those used for the light-scattering assay (see below). Those containing 0.6 µM of HT-tagged protein are shown in Figures 6E–6G. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 15 min, and 10 µl of each was spotted on a 300-mesh carbon-coated grid for 1 min and wicked away with filter paper. Grids were washed with 10 µl H2O and stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min. The wash step was omitted for the reaction shown in Figure 6H. Control grids showed that ribbon-like structures only formed in the presence of HT-SlmA, FtsZ, and GTP.

Light-Scattering and Ribbon-Sedimentation Assays

Proteins were purified as detailed in the Supplemental Data. 90° angle light scatter was monitored in a Jobin Yvon Horiba Fluoro-Max-3 fluorometer by using a wavelength of 350 nm and slit widths of 1 mm. Reactions were kept at 30°C by using a water jacket. The reactions (150 µl) initially contained FtsZ (3 µM) in buffer A (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.2], 100 mM KCl, and 2.5 mM MgCl2). Once a baseline scatter signal was obtained, HT-tagged protein or storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 350 mM KCl, and 5% glycerol) was added and the baseline was reestablished. Finally, GTP or GDP (1 mM final) were added as indicated, and the change in light scattering was monitored. HT-tagged proteins were used at a range of concentrations, with qualitatively coherent results. Reactions containing 0.3 µM are shown in Figures 6A–6D.

To study the composition of the ribbons observed by EM, reactions (55 µl) containing FtsZ (6 µM), HT-SlmA (6 µM), BSA (6 µM), GTP (1 mM), or GDP (1 mM) were prepared in buffer B (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.2], 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgCl2) as indicated in Figure 6I and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The reactions were then centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 rpm in a microfuge at room temperature. The supernatant was reserved and mixed with an equal volume of 2× sample buffer, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 µl 1× sample buffer. The proteins in 20 µl of each fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained as described above. Note that the pellet fractions were twice as concentrated as the supernatant fractions. Prior to centrifugation, a 5 µl aliquot of each reaction was removed and used to prepare EM grids as described above. Again, ribbon-like structures were only observed in the reaction containing HT-SlmA, FtsZ, and GTP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Don Court, Elliot Crooke, Steve Elledge, Cynthia Hale, Laura Lackner, Brenley McIntosh, David Raskin, Barry Wanner, and Ry Young for strains and plasmids; Cynthia Hale for purified FtsZ and help with electron microscopy; and members of our laboratory for support and helpful comments. We also thank Jeff Errington and Ling Juan Wu for communicating their discovery of Noc prior to publication. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM57059. T.G.B. was supported by the Damon Run-yon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-1698-02).

Footnotes

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Supplemental References, one figure, and three tables and are available with this article online at http://www.molecule.org/cgi/content/full/18/5/555/DC1/.

References

- Aarsman ME, Piette A, Fraipont C, Vinkenvleugel TM, Nguyen-Disteche M, den Blaauwen T. Maturation of the Escherichia coli divisome occurs in two steps. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1631–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addinall SG, Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring formation in fts mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3877-3884.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldea M, Garrido T, Pla J, Vicente M. Division genes in Escherichia coli are expressed coordinately to cell septum requirements by gearbox promotors. EMBO J. 1990;9:3787–3794. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aussel L, Barre F-X, Aroyo M, Stasiak A, Stasiak AZ, Sherratt D. FtsK is a DNA motor protein that activates chromosome dimer resolution by switching the catalytic state of the XerC and XerD recombinases. Cell. 2002;108:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Howe KL, Marshall M, Sonnhammer EL. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:276–280. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Pringle JR. Use of a screen for synthetic lethal and multicopy suppressee mutants to identify two new genes involved in morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:1295–1305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. Screening for synthetic lethal mutants in Escherichia coli and identification of EnvC (YibP) as a periplasmic septal ring factor with murein hydrolase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:1255–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer PAJ, Crossley RE, Rothfield LI. A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the mini-cell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E.coli. Cell. 1989;56:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Blaauwen T, Buddelmeijer N, Aarsman ME, Hameete CM, Nanninga N. Timing of FtsZ assembly in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:5167–5175. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5167-5175.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Hajj HH, Zhang H, Weiss B. Lethality of a dut (deoxyuridine triphosphatase) mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1069–1075. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1069-1075.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J, Daniel RA, Scheffers DJ. Cytokinesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:52–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.52-65.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring NW, Gueiros-Filho F, Beckwith J. Premature targeting of a cell division protein to midcell allows dissection of divisome assembly in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2005;19:127–137. doi: 10.1101/gad.1253805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueiros-Filho FJ, Losick R. A widely conserved bacterial cell division protein that promotes assembly of the tubulin-like protein FtsZ. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2544–2556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, de Boer PAJ. Recruitment of ZipA to the septal ring of Escherichia coli is dependent on FtsZ, and independent of FtsA. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:167–176. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.167-176.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, Rhee AC, de Boer PAJ. ZipA-induced bundling of FtsZ polymers mediated by an interaction between C-terminal domains. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5153–5166. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5153-5166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, Meinhardt H, de Boer PAJ. Dynamic localization cycle of the cell division regulator MinE in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2001;20:1563–1572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry EJ. Bacterial cell division: regulating Z-ring formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:795–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Ryter A, Jacob F. Thermosensitive mutants of E.coli affected in the process of DNA synthesis and cellular division. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1968;33:677–693. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1968.033.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Lutkenhaus J. Topological regulation of cell division in E. coli. spatiotemporal oscillation of MinD requires stimulation of its ATPase by MinE and phospholipid. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Gogol EP, Lutkenhaus J. Dynamic assembly of MinD on phospholipid vesicles regulated by ATP and MinE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6761–6766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102059099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Saez C, Lutkenhaus J. Recruitment of MinC, an inhibitor of Z-ring formation, to the membrane in Escherichia coli: role of MinD and MinE. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:196–203. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.196-203.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain K, Begg KG, Salmond GPC, Donachie WD. ParD: a new gene coding for a protein required for chromosome partitioning and septum localization in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1987;1:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Lackner LL, de Boer PAJ. Targeting of (D)MinC/MinD and (D)MinC/DicB complexes to septal rings in Escherichia coli suggests a multistep mechanism for MinC-mediated destruction of nascent FtsZ-rings. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:2951–2962. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2951-2962.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner LL, Raskin DM, de Boer PA. ATP-dependent interactions between Escherichia coli Min proteins and the phospholipid membrane in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:735–749. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.735-749.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau IF, Filipe SR, Soballe B, Okstad OA, Barre FX, Sherratt DJ. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:731–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Youngren B, Sergueev K, Austin S. Segregation of the Escherichia coli chromosome terminus. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:825–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Ehrhardt DW, Margolin W. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12998–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin W. Spatial regulation of cytokinesis in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001;4:647–652. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(01)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt H, de Boer PAJ. Pattern formation in Escherichia coli: a model for the pole-to-pole oscillations of Min proteins and the localization of the division site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14202–14207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251216598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. Analysis of FtsZ assembly by light scattering and determination of the role of divalent metal cations. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:823–832. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.823-832.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization by SulA, an inhibitor of septation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2885–2890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder E, Woldringh CL. Actively replicating nucleoids influence positioning of division sites in Escherichia coli filaments forming cells lacking DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:4303–4314. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4303-4314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. Unique and overlapping roles for ZipA and FtsA in septal ring assembly in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2002;21:685–693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin DM, de Boer PAJ. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4971–4976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romberg L, Levin PA. Assembly dynamics of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ: poised at the edge of stability. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:125–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.012903.074300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfield L, Justice S, García-Lara J. Bacterial cell division. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:423–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih YL, Le T, Rothfield L. Division site selection in Escherichia coli involves dynamic redistribution of Min proteins within coiled structures that extend between the two cell poles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232225100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Margolin W. Effects of perturbing nucleoid structure on nucleoid occlusion-mediated toporegulation of FtsZ ring assembly. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3951–3959. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3951-3959.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Yu X-C, Margolin W. Assembly of the FtsZ ring at the central division site in the absence of the chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:491–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto TH, Rowland SL, King GF. The dimerization function of MinC resides in a structurally autonomous C-terminal domain. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6684–6687. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6684-6687.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JX, Janmey PA. The polyelectrolyte nature of F-actin and the mechanism of actin bundle formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8556–8563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer NOE, Huls PG, Woldringh CL. Object-Image: an interactive image analysis program using structured point collection. Binary. 1994;6:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Weart RB, Levin PA. Growth rate-dependent regulation of medial FtsZ ring formation. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:2826–2834. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.9.2826-2834.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LJ, Errington J. Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2004;117:915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X-C, Margolin W. FtsZ ring clusters in min and partition mutants: role of both the Min system and the nucleoid in regulating FtsZ ring localization. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:315–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X-C, Margolin W. Deletion of the min Operon Results in Increased Thermosensitivity of an ftsZ84 Mutant and Ab-normal FtsZ Ring Assembly, Placement, and Disassembly. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6203–6213. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6203-6213.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.