Abstract

Purpose

This study sought to determine whether the effects of three parent-coached language interventions, two focused on augmented communication using a speech generating device and one only on speech, for toddlers with developmental delays and fewer than 10 words (Romski et al., in press) generalized to children’s joint engagement during interactions with parents that took place outside the intervention context.

Method

Fifty-seven toddlers who participated in one of three parent-coached language interventions were observed both pre- and post-intervention interacting with their parents using a Communication Play Protocol that produced samples of communication related to social-interacting, requesting, and commenting. Their engagement states were reliably coded from the videorecords of these interactions.

Results

Symbol-infused joint engagement of children in all three intervention groups increased significantly from pre- to post-intervention. The amount of symbol-infused joint engagement observed post-intervention was significantly associated with whether or not the child produced spoken words and, for children in the two augmented conditions, the number of augmented words used during the last intervention session.

Conclusions

The effects of parent-coached augmented language interventions generalize to children’s engagement in child-parent interactions outside the intervention context in ways that may facilitate additional language acquisition.

Promoting the generalization of intervention gains has long been recognized as a central goal of early language interventions for children who are not speaking and as a key justification for broadening the intervention context and for training parents as interventionists (e.g., Harris, 1975; Warren, 1988; Warren & Kaiser, 1986), yet all too often generalization is not adequately addressed when intervention outcomes are assessed (Schlosser & Lee, 2000; Snell, Chen, & Hoover, 2006). In this research note, we examine the generalization of successful parent-coached augmented language interventions for young children with severe developmental and language delays (Romski et al., in press, this journal). Specifically, we ask whether significant gains in vocabulary acquisition within the intervention setting are associated with significant gains in the child’s symbol-infused joint engagement during parent-child interactions that take place outside the intervention setting.

We chose to assess the effect of interventions on children’s joint engagement because of recent evidence indicating that the form and scope of joint engagement with their caregiver changes decisively as language is acquired and that participation in certain forms of joint engagement bodes well for further language development (Adamson, Bakeman, & Deckner, 2004; Adamson, Bakeman, Deckner, & Romski, 2009). By definition, joint engagement occurs when the child is actively attending to the same event as his social partner who may act in ways that enrich the child’s experience with actions and symbols well beyond what might occur during periods of solitary object engagement.

Forms of joint engagement change developmentally. Prior to the acquisition of language, infants typically develop ways to sustain periods of joint engagement during which they are actively involved with the same object or event as their caregiver (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984). During these periods, children may focus solely on the shared event (a state called supported joint engagement) or they may also actively acknowledge their social partner by repeatedly coordinating their attention between the partner and the shared event (a state called coordinated joint engagement), often by visually referencing the parent at critical junctures in the interaction. Once this pre-verbal communicative structure is consolidated, symbol-infused joint engagement rapidly increases between 18 and 30 months of age in typically developing toddlers (Adamson, et al., 2004), and it often emerges, albeit later, in young children with autism and Down syndrome (Adamson, et al., 2009). For an episode of joint engagement to be considered symbol-infused (SI), the child must act in ways that clearly indicate attention to symbols as well as to shared objects and actions by, for example, speaking (“A doll!”) or following the mother’s specific statements (e.g., correctly placing the object when the mother says “Put the doll to bed”). Symbol infusion can occur during episodes of either coordinated or supported joint engagement. For example, joint engagement would be coded both symbol-infused and coordinated if the child looks at the parent and smiles each time one of them names puzzle pieces they are sharing. A similar episode would be coded both symbol-infused and supported if the child actively focused on the shared naming activity, but did not actively acknowledge the parent’s participation. The infusion of symbols into periods of joint engagement increases the richness and scope of communication (Adamson & Bakeman, 2006), and it provides an important context for further language development (Adamson et al., 2004; 2009).

When a young child with developmental delay is unable to speak, the transition to SI joint engagement is likely to be severely compromised even if he or she is able to sustain periods of nonsymbol-infused supported and coordinated joint engagement. Thus, one important goal for early intervention with toddlers who have severe language deficits is to stimulate the uptake and use of symbols so that the child acquires a means to engage with partners in symbol-infused interactions that in turn may stimulate additional vocabulary acquisition.

This research note reports data for 57 children and their parents systematically observed before intervention began and soon after the last intervention session using a Communication Play Protocol (CPP, Adamson et al., 2004; 2009). Not included were 5 of the 62 children in the intervention study (Romski et al., in press) who did not complete the CPP due to scheduling difficulties or family moves. Of this sample, 39 children were male and 18 female; 15 were African-American, 6 Asian-American, and 36 European-American. Their mean ages during the pre- and post-intervention CPPs were 30.7 and 35.6 months (SDs = 4.5 and 4.7), respectively. All of the children were essentially nonspeaking at its onset. Participant selection criteria included not having begun to talk, which was operationally defined as a vocabulary of at most 10 intelligible spoken words and a score of less than 12 months on the expressive language scale of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995). Medical etiology included genetic syndromes, seizure disorders, cerebral palsy, or unknown medical etiology.

Each parent-child dyad (53 mothers, 4 fathers) was randomly assigned to one of three intervention conditions. As described in Romski et al. (in press), two of the interventions employed augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) that used speech-generating devices (SGDs) to produce digitized speech (ASHA, 2002). The two AAC interventions varied in terms of focus on augmented input (Augmented Communication-Input; AC-I), or output (Augmented Communication-Output; AC-O), whereas the third focused on speech alone (Spoken Communication; SC). Intervention consisted of 24 30-minute sessions, with the parent gradually assuming the role of lead communicative partner (Romski, Sevcik, Adamson, Cheslock, & Smith, 2007). The primary focus of the intervention was vocabulary acquisition and use. The project’s SLP guided each parent to define a list of vocabulary items appropriate to the intervention routines that his or her child did not comprehend or produce in speech or sign. Target items were represented as spoken words or as augmented words on the SGD using Picture Communication Symbols (PCS; Mayer-Johnson, 1981). Each child began with 15 yet to be learned vocabulary items; during the last intervention session the mean target vocabulary size had increased from 0 to 23, 22, and 16 for children in the AC-O, AC-I, and SC interventions, respectively. Twenty-five of the 62 children produced one or more of their target words using speech during the final intervention session, and all but one of the children in the augmented groups produced one or more of their target words using the SGD.

To determine whether the increase in vocabulary evident at the end of intervention would increase SI joint engagement outside the intervention context, we observed each child and parent in the Communication Play Protocol (CPP; Adamson et al., 2004; 2009), a semi-naturalistic procedure that produces a sample of the child’s current communication during six 5-min scenes that encourage interactions in three communicative contexts: social interacting (sharing music; taking turns), requesting (gaining toys from a shelf, help playing with complicated toys), and commenting (sharing pictures, discussing objects in a container). The CPP was videorecorded through one-way mirrored windows in a playroom that had not been used during the intervention. All parents in the AC-O condition and 15 of 19 in the AC-I condition brought the SGD to the post-intervention CPP.

As in Adamson et al. (2004; 2006), coders segmented the CPP video records into engagement states that characterized the child’s active focus on people, objects, and symbols. During this process, coders identified states of non-SI supported, non-SI coordinated, SI supported, and SI coordinated engagement. This coding scheme followed the advised strategy of arranging codes in mutually exclusive sets and defining them more molecularly than may be used for subsequent analyses (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997). Recording was continuous, times were recorded to the nearest second, and percentages of time for the various states were computed for each child. Based on a 15% sample of the corpus, Cohen’s kappa for interobserver agreement (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997) was .75, a value Fleiss (1981) characterized as excellent.

Of primary interest for this report is the state of symbol-infused joint engagement. For analysis, the percent of time in SI joint engagement was formed by summing SI supported and SI coordinated joint engagement percents. Similarly, supported and coordinated percents were formed by summing the appropriate non-SI and SI percents. Then the total joint engagement percent was the sum of the supported and coordinated percents.

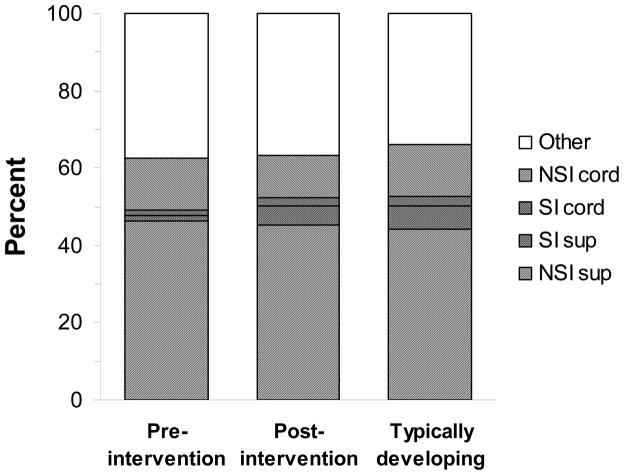

We found evidence that gains in symbol use evident during the last session of the intervention generalized to symbol use in non-intervention interactions. First, we investigated whether time spent in various joint engagement states changed from pre- to post-intervention. Figure 1 (see also Table 1) shows that time spent in joint engagement overall and in non-SI forms of joint engagement changed little and was comparable to the rate for typically-developing 18-month olds (Adamson et al., 2004). As expected, prior to intervention the children devoted very limited time to SI joint engagement (the shaded bands in the middle of the bars) even though they were often able to sustain periods of nonsymbol-infused joint engagement (unshaded bands at top and bottom). The proportion of time children spent in SI joint engagement was greater post- than pre-intervention. Specifically, the proportion of time engaged in symbol-infused joint engagement changed from an average of 2.7% to 7.1%, F(1,56) = 14.4, p < .001, pη2= .21 (i.e., from an average of 49 to 128 seconds). By comparison, the amount of supported (right-upward stripes) and coordinated (right-downward stripes) joint engagement did not change significantly.

Figure 1.

Mean joint engagement state percentages for the pre- and post-intervention groups and, for comparison, for typically-developing toddlers at 18 months of age from an earlier study (Adamson et al., 2004). NSI cord = non-symbol-infused coordinated joint engagement, SI cord = symbol-infused coordinated joint engagement, SI sup = symbol-infused supported joint engagement, and NSI sup = non-symbol-infused supported joint engagement. Other includes time spent in object engagement, unengaged, and person engagement. Right-upward strips represent supported and right-downward stripes represent coordinated joint engagement; gray shaded stripes in the middle represent their overlap with symbol-infused joint engagement.

Table 1.

Joint Engagement Statistics

| Joint engagement | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | pη2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 62 (18) | 63 (18) | .004 | .62 |

| Coordinated | 15 (16) | 13 (13) | .025 | .23 |

| Supported | 48 (14) | 50 (15) | .032 | .18 |

| Symbol-infused | 2.7 (3.8) | 7.1 (9.7) | .205 | <.001 |

Note. N = 57. Scores are mean percentages of time (standard deviations in parentheses). Coordinated and supported means may not sum exactly to the total mean due to rounding. Partial eta-squared is from a repeated measures analysis of variance.

The increase in SI engagement during the CPP was clearly associated with the child’s use of symbols during the last intervention session. Considering all children, the 25 children who used spoken words in the last intervention session were more often observed in SI joint engagement during the post-intervention CPP than the 32 children who did not (point bi-serial r = .46, Ms = 12.1% vs. 3.3%; η2 = .21; p <.001). By comparison, there was no significant difference in the percentage of time spent in supported or coordinated joint engagement. Considering only the children in the two augmented communication groups, the number of augmented words used in the last intervention session was associated with more time spent in SI joint engagement during the post-intervention CPP (r = .49, p = .001). Correlations with supported and coordinated joint engagement were .35 and .02, p =.027 and .88, respectively.

These findings suggest that a young child’s acquisition and use of spoken and augmented words during a parent-coached intervention may generalize to parent-child interactions that occur in non-intervention settings. It is particularly noteworthy that even modest gains in vocabulary for a child who is initially not speaking may be associated specifically with the emergence of symbol-infused joint engagement, a state that has been shown to foster further language acquisition in typically-developing toddlers and in young children with autism and with Down syndrome (Adamson et al., 2004; 2009). The documentation of this important developmental milestone in very young children who prior to intervention were essentially nonspeaking suggests that it will be informative both theoretically and clinically to learn more about how parents generalize strategies learned during the intervention to non-intervention settings in ways that can facilitate the child’s attention to and use of symbols. Further, this finding lends support to efforts to assess the effects of intervention over longer time spans to determine if initial generalization may result in fundamental changes in social interactions which in turn can stimulate further language gains.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by grants NIH DC-03799 and NIH HD-35612. We thank the families who participated in this study. We also acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of Pamela K. Rutherford, who helped manage the data set; Deborah F. Deckner, who coordinated engagement state data collection; and Melissa Cheslock, who coordinated the interventions. In addition, we thank Alicia Brady, Jesse Centrella, Sara Dowless, Ramona Blackman Jones, Tanya Kobek, P. Brooke Nelson, Lauren Pierre, Janis Sayre, Ashlyn Smith, Anjali Vasudeva, and Rebekah Walker for assisting in implementing the Communication Play Protocol and coding the video records.

References

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R. The development of displaced speech in early mother-child conversations. Child Development. 2006;77:186–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF. The development of symbol-infused joint engagement. Child Development. 2004;75:1171–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF, Romski MA. Joint engagement and the emergence of language in children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:84–96. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0601-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Adamson LB. Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant interaction. Child Development. 1984;55:1278–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Gottman JM. Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale P, Reznick S, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, Pethick S, Reilly J. MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. San Diego: Singular Publishing Co; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. New York: John Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Harris SL. Teaching language to nonverbal children – with emphasis on problems of generalization. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:565–580. doi: 10.1037/h0076903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Johnson Co. Picture Communication Symbols. Stillwater, MN: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen E. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, Cheslock M, Smith A. Parents can implement AAC interventions: Ratings of treatment implementation across early language interventions. Early Childhood Services. 2007;1:100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, Cheslock M, Smith A, Barker RM, Bakeman R. Randomized comparison of augmented and non-augmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53:350–364. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0156). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser RW, Lee DL. Promoting generalization and maintenance in augmentative and alternative communication: A meta-analysis of 20 years of effectiveness research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 2000;16:208–226. [Google Scholar]

- Snell ME, Chen LY, Hoover K. Teaching augmentative and alternative communication to students with severe disabilities: A review of intervention research 1997–2003. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2006;31:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Warren SF. A behavioral approach to language generalization. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1988;19:292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Warren SF, Kaiser AP. Generalization of treatment effects by young language-delayed children: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Speech & Hearing Disorders. 1986;51:239–251. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5103.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]