Abstract

Background

Six1 plays an important role in the development of several vertebrate organs, including cranial sensory placodes, somites and kidney. Although Six1 mutations cause one form of Branchio-Otic Syndrome (BOS), the responsible gene in many patients has not been identified; genes that act downstream of Six1 are potential BOS candidates.

Results

We sought to identify novel genes expressed during placode, somite and kidney development by comparing gene expression between control and Six1-expressing ectodermal explants. The expression patterns of 19 of the significantly up-regulated and 11 of the significantly down-regulated genes were assayed from cleavage to larval stages. 28/30 genes are expressed in the otocyst, a structure that is functionally disrupted in BOS, and 26/30 genes are expressed in the nephric mesoderm, a structure that is functionally disrupted in the related Branchio-Otic-Renal (BOR) syndrome. We also identified the chick homologues of 5 genes and show that they have conserved expression patterns.

Conclusions

Of the 30 genes selected for expression analyses, all are expressed at many of the developmental times and appropriate tissues to be regulated by Six1. Many have the potential to play a role in the disruption of hearing and kidney function seen in BOS/BOR patients.

Keywords: preplacodal ectoderm, pan-placodal region, otocyst, olfactory, cranial ganglia, BOS syndrome, BOR syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Vertebrate Six genes are highly related to the Drosophila sine oculis gene that is critical for fly visual system development (Cheyette et al., 1994). They play major roles in the development of the eye, but also in other sense organs, cranial sensory ganglia, the central nervous system, muscle, kidney, genitalia, limb buds and lungs (Oliver et al., 1995; Kawakami et al., 1996; Ohto et al., 1998; Spitz et al., 1998; Pandur and Moody, 2000; Ghanbari et al., 2001; Fougerousse et al., 2002; Laclef et al., 2003; Bessarab et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2003; Brodbeck and Englert, 2004; Ozaki et al., 2004; Zou et al., 2004; Brugmann and Moody 2005; Grifone et al., 2005; Konishi et al., 2006; Zou et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Ikeda et al., 2010; Sato et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2011). Several experiments indicate that Six1 has a central role in controlling development of the cranial sensory placodes, which are patches of thickened embryonic ectoderm that will give rise to the anterior pituitary, olfactory sensory epithelium, lens, auditory and vestibular inner ear structures, and the large, distally-located neurons of the cranial sensory ganglia (reviewed in Schlosser, 2007; Schlosser, 2010; Streit, 2004; Bailey and Streit, 2006; Streit, 2007; Ladher et al., 2010; Park and Saint-Jeannet, 2010; Graham and Shimeld, 2013; Saint-Jeannet and Moody, 2014). Loss of Six1 function or repression of its downstream targets in Xenopus, chick and zebrafish results in the loss of markers specific to the pre-placodal region (PPR) and placodes (Brugmann et al., 2004; Bricaud and Collazo, 2006, 2011; Schlosser et al., 2008; Christophorou et al., 2009). In particular, otic placode defects (Christophorou et al., 2009), and loss of inner ear hair cells (Bricaud and Collazo, 2006; Bricaud and Collazo, 2011) are observed. Six1-null mice have olfactory, inner ear and cranial sensory ganglion malformations (Oliver et al., 1995; Laclef et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2003; Ozaki et al., 2004; Zou et al., 2004; Konishi et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Ikeda et al., 2010). Conversely, Six1 gain-of-function specifically in the PPR expands the domains of placode genes in frog and chick (Brugmann et al., 2004; Christophorou et al., 2009), indicating that it is a key regulator of placode fate.

In humans, SIX1 mutations can cause Branchio-Otic Syndrome (BOS, specifically BOS3; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] #608389; www.omim.org), whose phenotypes include mild craniofacial defects and significant hearing loss (Ruf et al., 2004). Nine mutations in BOS3 patients from 16 unrelated families have been reported to date. Seven are missense mutations in an N-terminal domain, called the Six Domain (SD; Kawakami et al., 2000), which disrupt interactions with co-factors, and two are mutations in the homeodomain, which disrupt interactions with the DNA (Ruf et al., 2004; Ito et al., 2006; Sanggaard et al., 2007; Kochhar et al., 2008; Patrick et al., 2009; Noguchi et al., 2011; Patrick et al., 2013). In zebrafish, expression of mutant Six1 mRNA that carries a BOS patient mutation in the SD (R110W) interferes with the Six1/Eya1 interaction that promotes hair cell formation (Bricaud and Collazo, 2011). The Catweasel (Cwe) mouse mutant harbors a missense mutation in the SD (Bosman et al., 2009) that is similar to at least one BOS family (Mosrati et al., 2011). Heterozygous-Cwe mice have an ectopic row of hair cells in the cochlea and homozygous-Cwe mice have a loss of hair cells in the cochlea, semicircular canals and utricle. Mutations in the Six1 co-factor called EYA1 (Ohto et al., 1999) causes BOS1 (OMIM #602588) and the related Branchio-Otic-Renal (BOR1; OMIM #113650) syndrome, in which kidney development is additionally disrupted (Abdelhak et al., 1997; Kumar et al., 1997; Ozaki et al., 2002; Rodriguez-Soriano, 2003; Spruijt et al., 2006). However, mutations in Six1 and Eya1 only account for about half of the BOS and BOR cases, indicating that there are other genes in the Six/Eya genetic pathway that contribute to these syndromes.

To identify potential causative genes for BOS and BOR, we generated a more complete list of genes likely to be regulated by the Six1 transcription factor. We expressed Six1 in animal cap ectodermal explants (ACs), which were raised to an early neural plate stage at which time Six1 is highly expressed in the PPR, and compared their expression profile to control, uninjected ACs that will give rise to non-neural epidermis. Herein we describe the expression patterns of 30 genes that were significantly different between these two data sets, most of which have not been previously characterized in Xenopus. We also identified several chick homologues and present their expression patterns. The majority of the genes characterized are expressed at the correct times to be regulated by Six1, particularly in the otic placode and nephric mesoderm. Thus, they may play a role in the disruption of hearing and kidney functions seen in BOS/BOR patients.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To identify a more complete list of genes likely to act downstream of Six1 during development, animal cap ectoderm (AC) was explanted at blastula stages from embryos microinjected with Six1 mRNA at the 2-cell stage and from control, uninjected sibling embryos. Explants were cultured to neural plate stages when the PPR is specified (Ahrens and Schlosser, 2004; Pieper et al., 2012), and prepared for microarray expression assays as previously described (Yan et al., 2010).

Six1 alters the expression of numerous genes in ectodermal explants

Of the ~14,400 genes represented on the Affymetrix GeneChip v1, 72 were expressed at a >2-fold (p<0.05, ANOVA) higher level in the Six1-injected ACs (Table 1). Gene identities were determined by BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and GOs were determined by searching the Xenopus and mouse gene databases (http://www.xenbase.org; http://www.informatics.jax.org). Based on gene title or most similar match, the largest category of the up-regulated genes is “unknown” function (44.4%). Genes with known function were most commonly involved in metabolic processes (15.2%), signaling (11.1%), and transcription (9.7%); a small number of other functions also were identified (Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Genes up-regulated >2 fold by Six1 in microarray assays

| Affymetrix Probe set ID | Fold Change | Accession Number | Gene Title, Unigene Cluster or EST name | GO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xl.19919.1.A1_at | 4.613 | BQ400635 | UniGene Xl.940; neuropilin1 (nrp1), aka A5-protein | signaling |

| Xl.17484.1.A1_at | 4.428 | BG812762 | EST: daf30h01.y1; similar to arrestin beta2 (arrb2) | metabolism |

| Xl.24006.1.S1_at | 4.300 | AW640051 | UniGene Xl.78601; aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family, member A1 (aldh7a1) | metabolism |

| Xl.3228.1.A1_at | 3.811 | BG022063 | EST: dg21d06.x1 | unknown |

| Xl.26192.1.A1_at | 3.561 | CD324856 | EST: AGENCOURT_14164067; most similar to Xenopus laevis clone CH219-20I13 | unknown |

| Xl.20029.2.S1_a_at | 3.484 | M80798.1 | PDGFα receptor | signaling |

| Xl.21032.1.S1_at | 3.413 | AF546707.1 | Cryptic tubulin | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.6623.1.S1_at | 3.200 | BU900288 | UniGene Xl.22052; heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear protein R (hnrnpr) | nuclear |

| Xl.23944.1.S1_at | 3.057 | BG885936 | UniGene Xl.37859; hypothetical protein LOC100037047 | unknown |

| Xl.12902.1.A1_at | 3.046 | BJ092409 | EST: BJ092409 | unknown |

| Xl.19820.1.A1_at | 3.030 | BQ399495 | EST: NISC_mp03h05.x1; most similar to Xenopus laevis clone CH219-33D5 | unknown |

| Xl.2439.1.A1_at | 2.996 | BG023545 | UniGene Xl.2439; hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase1 (hrpt1) | metabolism |

| Xl.23880.1.A1_at | 2.989 | BJ083747 | UniGene Xl.4536; RNA binding motif protein 42 (rbm42-b) | RNA binding |

| Xl.19782.1.A1_at | 2.958 | BQ398913 | UniGene Xl.52003; hypothetical protein LOC 414689 | unknown |

| Xl.12791.1.A1_at | 2.944 | BJ090916 | EST: BJ090916 | unknown |

| Xl.23533.1.S1_at | 2.918 | BC044278.1 | Uncx4.1 homeobox | transcription |

| Xl.19504.1.S1_at | 2.879 | BQ386473 | UniGene Xl.19504; xyloside xylosyltransferase 1 (xxylt1) | metabolism |

| Xl.11568.1.S1_a_at | 2.859 | AW872117 | EST: db22e02.y1; matches several genes at 5′ end | unknown |

| Xl.21833.1.A1_at | 2.839 | BG345845 | EST: dg42a07.y1 | unknown |

| Xl.17880.1.A1_at | 2.826 | BG812152 | EST: daf66c03.x1 | unknown |

| Xl.4077.2.A1_at | 2.780 | BF024988 | EST: dc82d05.x1; similar to mitogen-activated protein kinase binding protein 1 | signaling |

| Xl.15434.2.A1_at | 2.689 | BJ079756 | UniGene Xl.15434; N-acetylglucomsamine-1-phosphate transferase, gamma subunit (gnptg) | metabolism |

| Xl.17452.3.A1_at | 2.665 | BG409705 | UniGene Xl.54929; cyclin L1 (ccnl1) | transcription |

| Xl.3765.1.A1_at | 2.641 | BF428468 | UniGene Xl.6193; Polymerase (RNA) II polypeptide I (polr2i) | transcription |

| Xl.17267.1.S1_at | 2.638 | BM262144 | UniGene Xl.17267; Predicted hamartin-like (aka tuberous sclerosis 1; tsc1) | protein binding |

| Xl.6714.1.S1_at | 2.620 | CD360857 | UniGene Xl.6714; MACRO domain containing protein 2 (macrod2) | metabolism |

| Xl.8697.1.A1_at | 2.618 | AW764878 | UniGene Xl.8697; empty spiracles homeobox 2 (emx2) | transcription |

| Xl.20538.1.S1_at | 2.546 | CD327089 | UniGene Xl.20538; strongly similar to malignant fibrous histiocytoma amplified sequence 1 (mfhas1) | unknown |

| Xl.21807.1.S1_at | 2.526 | BC041247.1 | Guanine nucleotide binding protein 13 gamma | nuclear |

| Xl.16468.1.A1_at | 2.513 | BJ048720 | EST: BJ048720; most similar to Xenopus laevis clone CH219-51A4 | unknown |

| Xl.26433.1.A1_at | 2.502 | BJ077709 | EST: BJ077709 | unknown |

| Xl.15912.2.A1_at | 2.482 | BJ055680 | UniGene Xl.18703; phosphatase, orphan 2 (phospho2) | metabolism |

| Xl.14658.1.A1_at | 2.479 | BJ052130 | EST: BJ052130 | unknown |

| Xl.9485.1.A1_x_at | 2.479 | BG264616 | UniGene Xl.10876; strongly similar to Xenopus tropicalis predicted nucleoporin 133kDA (nup133) | nuclear |

| Xl.11066.1.A1_at | 2.449 | AW764707 | UniGene Xl.11066; autophagy related 4D, cysteine peptidase (atg4d) | metabolism |

| Xl.9896.1.A1_at | 2.432 | BG019991 | EST: dc46e08.x1; most similar to Xenopus tropicalis clone CH216-157J16 | unknown |

| Xl.25648.2.A1_at | 2.398 | BI940543 | UniGene Xl.76517; strongly similar to Xenopus tropicalis predicted t-lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1 (tiam1) | signaling |

| Xl.21726.1.S1_at | 2.323 | CA790591 | EST: AGENCOURT_10301409 | unknown |

| Xl.18330.1.S1_at | 2.311 | BJ049080 | UniGene Xl.64976; moderately similar to Xenopus tropicalis predicted zinc finger protein 335-like | transcription |

| Xl.4441.1.A1_at | 2.305 | BF072093 | EST: db51d10.x1 | unknown |

| Xl.11394.1.A1_at | 2.297 | AW639023 | UniGene Xl.11394; strongly similar to JNK1/MAPK8-associated membrane protein (jkamp) | metabolism |

| Xl.535.2.S1_a_at | 2.290 | AF172400 | P75 neurotrophin receptor a-2 (p75NTRa) | signaling |

| Xl.8063.1. S1_at | 2.255 | AY099224 | Tumorhead (trhd-a) | intracellular transport |

| Xl.22358.1.A1_at | 2.249 | BG021407 | UniGene Xl.34405; E74-like transcription factor (elf2) | transcription |

| Xl.14141.1.A1_at | 2.192 | BJ079748 | EST: BJ079748; most similar to ribosomal protein L14 (rpl14) | ribosomal biogenesis |

| Xl.2873.1.A1_at | 2.187 | BG018413 | UniGene Xl.18253; Uncharacterized LOC 100037177 | unknown |

| Xl.26415.1.S1_at | 2.187 | CD361045 | UniGene Xl.26415; testis, prostate and placenta expressed (tepp) | unknown |

| Xl.18588.1.S1_at | 2.184 | BI442945 | UniGene Xl.77328; Uncharacterized LOC496297 | unknown |

| Xl.3096.1.A1_at | 2.171 | BJ085327 | UniGene Xl.57373; transmembrane and coiled-coiled domain family 2 (tmcc2) | membrane |

| Xl.13487.1.A1_at | 2.164 | CB564242 | UniGene Xl.13487; Uncharacterized protein MGC154312 | unknown |

| Xl.11706.1.S1_at | 2.163 | AY221506.1 | Putative polyA-binding protein (PABPN2) | translation |

| Xl.11463.3.S1_a_at | 2.162 | BU917037 | UniGene Xl.19374; G protein-coupled receptor kinase-interacting ArfGAP (git2) | intracellular transport |

| Xl.1095.1.S1_at | 2.162 | S71764.1 | Sperm-specific basic nuclear protein 5 (sp5) | signaling |

| Xl.13738.1.A1_at | 2.149 | BJ075690 | EST: BJ075690; most similar to WNT-inhibitory factor 1 (wif1) | signaling |

| Xl.16242.1.A1_at | 2.145 | BJ100481 | UniGene Xl.16242; strongly similar to sperm associated antigen 16 protein-like (spag16) | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.16853.1.S1_at | 2.137 | BG579925 | UniGene Xl.46098; weakly similar to predicted protein FAM178A | unknown |

| Xl.25532.1.A1_at | 2.127 | BJ055327 | UniGene Xl.25532; strongly similar to hypothetical protein LOC100488559 | unknown |

| Xl.18739.1.S1_at | 2.119 | BI445731 | UniGene Xl.18739; KIAA1456 | metabolism |

| Xl.12870.1.A1_at | 2.119 | BJ082868 | UniGene Xl.12870; moderately similar to zinc finger protein 665-like | unknown |

| Xl.21416.1.S1_at | 2.107 | AW638131 | UniGene Xl.28718; Pseudouridylate synthase 7 homolog (pus7) | unknown |

| Xl.12763.1.A1_at | 2.104 | BJ082426 | EST: BJ082426 | unknown |

| Xl.21588.1.A1_at | 2.093 | AB054535.1 | Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase (hs6st1) | metabolism |

| Xl.13831.3.S1_at | 2.088 | BJ075928 | UniGene Xl.72612; moderately similar to predicted coiled-coiled domain-containing C6orf97 | unknown |

| Xl.9563.1.S1_at | 2.078 | AF480430.1 | Pbx1b | transcription |

| Xl.6583.1.S1_at | 2.078 | AW635173 | UniGene Xl.6583; weakly similar to wars2 gene product | translation |

| Xl.15729.1.A1_at | 2.066 | BJ050119 | EST: BJ050119 | unknown |

| Xl.401.1.S1_at | 2.058 | AF032383 | Metalloprotease-disintegrin (MDC11b, aka adam11) | proteolysis |

| Xl.3198.1.A1_at | 2.050 | BG021827 | UniGene Xl.53283; testis expressed 26 (tex26) | unknown |

| Xl.19719.1.A1_at | 2.049 | BQ398489 | EST: NISC_mo08b08.x1; moderately similar to Xenopus laevis canopy FGF signaling regulator 1 (cnpy1) | signaling |

| Xl.8108.1.A1_at | 2.045 | BJ047639 | UniGene Xl.47742; Uncharacterized LOC100036828 | unknown |

| Xl.9031.1.A1_x_at | 2.019 | BG579679 | UniGene Xl.9031; Chromosome 5 open reading frame 22 (c5orf22) | unknown |

| Xl.12209.1.A1_at | 2.010 | BJ082981 | EST: BJ082981; most similar to Xenopus laevis hypothetical protein MGC115205 | unknown |

Figure 1.

Gene Ontology analysis of the genes whose expression levels in animal cap explants were significantly altered >2 fold by Six1 in a microarray analysis. A. The proportions of genes up-regulated by Six1 in each of several GO functional classes. B. The proportions of genes down-regulated by Six1 in each of several GO functional classes.

Of these 72 genes, only a few have previously been implicated in cranial placode development: Nrp1, PDGFα receptor and p75 neurotrophin receptor. Nrp1-semaphorin signaling regulates neural crest migration, which affects placode contributions to cranial ganglia in Xenopus and mouse (Koestner et al., 2008; Schwarz et al. 2008). PDGF signaling can induce ophthalmic placode formation (McCabe and Bronner-Fraser, 2008) and in combination with FGF plays a role in PPR specification (Kwon et al., 2010). The p75 neurotrophin receptor is expressed on both neural crest and placode cells in developing cranial ganglia (Vazquez et al., 1994). In addition, several of the identified genes have functions that are similar to those published for Six1, supporting the idea that they may be in the same genetic pathway. For example, Six1 is known to regulate cell proliferation and is overexpressed in several cancers (Ford et al., 1998; Coletta et al., 2004; Patrick et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2013); genes known to be involved in cell cycle regulation (Uncx4.1; Mitogen-activated protein kinase binging protein 1, Cyclin L1; Trhd1-a) and cell movement/cancer (Tiam1, Elf2, Nrp1, p75, Pbx1; MDC11b) were found in the up-regulated category. Placode development in several vertebrates is enhanced by FGF signaling and reduced by Wnt signaling (Phillips et al., 2001; Leger and Brand, 2002; Maroon et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Brugmann et al., 2004; Ahrens and Schlosser, 2005; Litsiou et al., 2005; Martin and Groves, 2005; Matsuo-Takasaki et al., 2005; Bailey et al., 2006; Hong and Saint-Jeannet, 2007; Park and Saint-Jeannet, 2008; Esterberg and Fritz, 2009; Patthey et al., 2008; Patthey et al., 2009; Kwon et al., 2010; Grocott et al., 2012); putative regulators of FGF (Cnpy1, Elf2, Ism1) and Wnt (Arrb2, Wif1) pathways were in the up-regulated category. We also searched those genes up-regulated >1.6 fold (p<0.05, ANOVA) to identify previously characterized genes that might be in the Six1 pathway based on published expression patterns (Table 2). Amongst these were genes expressed during cranial sensory placode (Ism1, Pax6, Irx1, Arnt), somite (Arnt, HoxA3) and/or kidney development (Arnt, Mdx4, Irx1).

Table 2.

Selected genes regulated >1.6 fold by Six1 in microarray assays

| Affymetrix Probe set ID | Fold Change | Accession Number | Gene Title | GO | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xl.4323.1.A2_at | 1.988 | BJ078437 | Ism1 | signaling | Pera et al., 2002 |

| Xl.418.1.S1_at | 1.876 | NM_001090739.1 | Nfya | transcription | Li et al, 1998 |

| Xl.647.7.S1_at | 1.825 | AF154558.1 | Pax6 | transcription | Li et al., 1997; Hirsch and Harris, 1997 |

| Xl.69.1.S1_at | 1.757 | AJ001834.2 | Irx1 | transcription | Gomez-Skarmeta et al., 1998 |

| Xl.12075.1.S1_at | 1.740 | AY036894.1 | Arnt | transcription | Bollerot et al., 2001 |

| Xl.7579.1.S1_at | 1.717 | BC077576 | TBC1 domain family, member 31 (tbc1d31) | Rab GTPase activator activity | |

| Xl.9439.1.S1_at | 1.674 | BC041731.1 | HoxA3 | transcription | Klein et al., 2002 |

| Xl.26468.1.S1_at | 1.637 | AF127040.1 | Mdx4 | transcription | Newman and Krieg, 1999 |

| Xl.4910.1.S1_at | 1.623 | BC126014 | Cell division cycle associated 7-like (cdca7l) | cell cycle | |

| Xl.1354.2.S1_at | 1.615 | MGC83633 | PAP associated domain 4 (papd4-a) | mRNA processing | Rouhana et al., 2005 |

| Xl.781.1.S1_at | −1.852 | AY029294.1 | otx1 | transcription | Kablar et al., 1996 |

| Xl.13309.1.S1_at | −1.832 | X53450 | snail1 | transcription | Sargent and Bennett, 1990 |

| Xl.20089.1.S1_at | −1.715 | BC042303.1 | foxi1 (xema) | transcription | Suri et al., 2005 |

| Xl.283.1.A1_at | −1.642 | X62053.1 | hoxA1 | transcription | Sive and Cheng, 1991 |

To assess the validity of the microarray results, we performed several experiments. First, we measured the expression of ten up-regulated genes by qPCR; 10/10 were expressed at higher levels in Six1-injected ACs compared to uninjected control ACs, half of which reached statistical significance (Table 3). Second, we knocked-down endogenous Six1 in whole embryos by injecting morpholino antisense oligonucleotides; this diminished the expression of 17/20 up-regulated candidates (Table 4). Figure 2 shows examples: loss of somite expression of Cdca7l; loss of neural crest expression of HoxA3; loss of neural tube expression of Ism1. Third, we increased Six1 expression: 12/20 up-regulated candidates showed expanded expression domains by injection of mRNAs encoding either wild-type Six1 or the activating Six1-VP16 construct, and 0/20 was expanded by the repressive EnR-Six1 construct (Table 4). As examples, Figure 2 shows examples: broader neural plate and/or neural crest expression by wild-type Six1 (BG022063, Nfya) or Six1-VP16 (Frizzled 10b, Pbx1); reduced Frizzled 10b by EnR-Six1. Although nearly all of the tested candidates require Six1, it was surprising that only about half of them were increased/expanded by wild-type or activating Six1. However, these results are consistent with SO activity in the fly eye field: overexpression rarely induces ectopic eye tissue (Jusiak et al., 2014) and it promotes eye fate mainly by repressing alternate fates (Anderson et al., 2010). Thus, many of the up-regulated genes identified by the microarray assay are likely downstream of Six1 based on published function in Xenopus, chick or mouse, published expression patterns and/or changes in expression after Six1 loss- or gain-of-function. However, Six1 ChIP analyses are required to confirm if any of these candidates are direct transcriptional targets.

Table 3.

qPCR analysis of expression levels in Six1-injected animal cap explants relative to control explants

| Fold expression over control | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | ||

| BJ02409 | 5.14 | <0.05 |

| BQ399495 | 3.49 | <0.05 |

| AF546707 | 3.37 | <0.05 |

| Pdgfra | 2.34 | <0.05 |

| BG885936 | 1.85 | >0.1 |

| Hrpt1-5047264 | 1.83 | <0.05 |

| Aldh7a1 | 1.72 | >0.1 |

| Hnrnpr | 1.71 | >0.1 |

| Arrb2-4740312 | 1.35 | >0.1 |

| XXylt1-6639045 | 1.35 | >0.1 |

| Down-regulated | ||

| MGC 114680 | 0.40 | >0.1 |

| Image 3399268 | 0.55 | <0.05 |

| Dnaja4.2-4930076 | 0.79 | >0.1 |

| Ralgds-4681426 | 1.08 | >0.1 |

| Cnfn1-a-6316571 | 1.25 | >0.1 |

Table 4.

Percentage of embryos showing altered expression domains of up-regulated genes in response to changes in Six1 activity

| Candidate | Diminished by Six1 MO knock-down (n) | Expanded by wild-type Six1 (n) | Expanded by Activating Six1-VP16 (n) | Expanded by Repressive EnR-Six1 (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nrp1/BQ400635 | 41.2 (17) | 4.8 (42) | 27.8 (18) | 0.0 (28) |

| Arrb2/BG812762 | 0.0 (20) | 0.0 (52) | 0.0 (13) | 0.0 (24) |

| BG022063 | 0.0 (20) | 5.9 (34) | 0.0 (8) | 0.0 (10) |

| LOC100037047 | 43.8 (16) | 15.6 (45) | 0.0 (10) | 0.0 (20) |

| BQ399495 | 0.0 (16) | 7.1 (28) | 0.0 (7) | 0.0 (20) |

| Hrpt1/BG023545 | 8.3 (24) | 2.1 (49) | 0.0 (12) | 0.0 (16) |

| Rmb42-b/BJ083747 | 45.0 (20) | 0.0 (47) | 0.0 (14) | 0.0 (16) |

| LOC414689 | 31.6 (19) | 0.0 (45) | 0.0 (12) | 0.0 (12) |

| Uncx4.1/BC044278.1 | 28.6 (14) | 0.0 (24) | 0.0 (11) | 0.0 (10) |

| Xxylt1/BQ386473 | 28.6 (14) | 0.0 (40) | 11.1 (18) | 0.0 (14) |

| Pbx1b/AF480430.1 | 64.3 (14) | 0.0 (41) | 85.0 (20) | 0.0 (14) |

| Ism1/BJ078437 | 50.0 (12) | 0.0 (31) | 0.0 (15) | 0.0 (15) |

| Frizzled10b | 57.1 (14) | 0.0 (23) | 72.2 (18) | 0.0 (10) |

| Nfya/NM_0-01090739.1 | 75.0 (16) | 0.0 (39) | 47.1 (17) | 0.0 (10) |

| Arnt/AY036894.1 | 54.5 (11) | 0.0 (41) | 0.0 (14) | 0.0 (9) |

| Tbc1d31/BC077576 | 26.7 (15) | 0.0 (53) | 10.0 (10) | 0.0 (11) |

| HoxA3/BC041731.1 | 71.4 (14) | 0.0 (33) | 53.8 (13) | 0.0 (7) |

| Mdx4 | 38.5 (13) | 0.0 (30) | 7.7 (13) | 0.0 (9) |

| Cdca7l/BC126014 | 66.7 (12) | 0.0 (46) | 0.0 (13) | 0.0 (11) |

| Papd4/MGC83633 | 66.7 (12) | 0.0 (21) | 0.0 (14) | 0.0 (8) |

Figure 2.

Examples of changes in gene expression of putative Six1 targets after knock-down of endogenous Six1 levels by injection of antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (Six1 MOs), increased levels of wild type Six1 by mRNA injection (Six1 WT), activation of Six1 targets by mRNA injection of an activating construct (Six1-VP16), or repression of Six1 targets by mRNA injection of a repressive construct (EnR-Six1) (see Brugmann et al., 2004 for validation of these constructs). Six1 MOs: Expression of Cdca7l in the segmenting somites (arrows on control [ctrl] side) is lost on the injected (inj) side (side views, anterior to left). Expression of HoxA3 in the neural crest (nc) is greatly reduced on the injected side, whereas hindbrain (hb) expression is maintained (side views, anterior to left). Expression of Ism1 is lost in the midbrain (arrow) (frontal view, dorsal to the top). Expression of IMAGE 3399268 is expanded in the neural plate (line depicts width from midline to lateral border) on the injected side (dorsal view, anterior to the bottom). Expression patterns of Cnfn1-a in the hatching gland (arrows) and of Snail1 in the migrating neural crest are reduced and disrupted on the injected sides (frontal views, dorsal to the top). Six1 WT: Expression of BG022063 is broader in the neural plate (line) and neural crest (bracket) on the injected side (frontal view, dorsal to the top). Expression of Nfya is broader in the neural tube (line) on the injected side (dorsal view, anterior to the top). Expression of IMAGE 3399268 in the segmented somites (arrows, ctrl side) is lost on the injected side (side views, anterior to left). Expression of IMAGE 4057931 in the neural crest (bracket), otocyst (oto) and trigeminal ganglion (arrow) is greatly diminished on the injected side (side views, anterior to left). Six1-VP16: Expression of Frizzled10b, Pbx1 and Zic2 in the neural plate is expanded (line) on the injected side (frontal views, dorsal to the top). EnR-Six1: Expression of Frizzled10b in the neural plate is reduced (line) on the injected side (frontal view, dorsal to the top). Expression of IMAGE 4057931 is reduced in the PPR (arrows on the control side; frontal view, dorsal to the top). Expression of Zic2 and Otx1 in the neural tube is reduced (line) on the injected sides (arrows; frontal views, dorsal to the top). In MO-injected embryos, injected sides were confirmed by the use of lysamine-labeled MOs (not shown). In mRNA-injected embryos, injected sides were confirmed by the presence of nuclear β-galactosidase lineage labeling (pink dots visible in most images).

Of the genes represented on the GeneChip, 58 were expressed at a >2-fold (p<0.05, ANOVA) lower level in the Six1-expressing ACs (Table 5). The largest category of the down-regulated genes is “unknown” function (36.2%). Genes with known function were most commonly involved in metabolic processes (10.3%), signaling (19.0%), and transcription (10.3%); a small number of other functions also were identified (Figure 1B). The expression of most of the 58 genes have not been characterized across Xenopus developmental stages, but by searching a mouse expression database (http://www.informatics.jax.org) we found that many of those for which there is an identified homologue are expressed in developing tissues regulated by Six1. These include: cranial placodes (Glcci1, Rcan1, Naga, Rilpl1, Etl4, Xspr2, Jun, Phb2, Mt1, Pigc, Gap43, Tusc3), neural crest (Zic2), muscle (Rcan1, Jun, Krm2, Phb2, Rras2, Pigc, Sytl1), and nephric mesoderm (Naga, Pik3r5, Cdc42ep2, Xspr2, Rab40B, Akt, Rras2, Pigc, Vwc2, Gap43, HNF1a, Sytl1, Tusc3). Several also are transcribed in tissues in which Six1 is not normally expressed. These include: neural plate/tube (Socs3, Glcci1, Dnaj4.2, Rhot1, Pik3r5, Axin2, Xspr2, Jun, Rab40b, Akt, Krm2, Metrn, Phb2, Akap2, Ap4m1, Rras2, Mt1, Zic2; Pigc, Vwc2, Gap43, HNF1a, Sytl1, Vta1, Tusc3), epidermis (Fgk, Cnfc1, Axin2, Krm2, Phb2, Krt18-a, Pigc, Tusc3) and mesoderm (Socs3, Pik3r5, Adam13, Xspr2; Jun, Krm2, Rras2, Mt1, Pigc, HNF1a). We also searched genes down-regulated >1.6 fold (p<0.05, ANOVA) to identify previously characterized genes expected to be repressed by Six1, based on studies in chick and Xenopus (Brugmann et al., 2004; Christophorou et al., 2009). Of note are genes expressed in neural plate (Otx1), neural crest (Snail1, HoxA1) and epidermis (Foxi1/Xema) (Table 2).

Table 5.

Genes down-regulated >2 fold by Six1 in microarray assays

| Affymetrix Probe set ID | Fold Change | Accession Number | Gene Title, Unigene Cluster or EST name | GO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xl.22313.1.S1_at | −3.876 | BC080322 | Xenopus laevis cDNA clone IMAGE 4174145 | unknown |

| Xl.26171.1.A1_s_at | −3.610 | BC079829 | Xenopus laevis cDNA clone IMAGE 3399268 | unknown |

| Xl.14963.1.A1_x_at | −3.378 | BG264797 | EST: daa32g06.x1; IMAGE 4057931; most similar to 5′biphosphate nucleotidase 1 (bpnt1) | metabolism |

| Xl.9924.1.A1_at | −3.322 | BG020210 | EST: dc48g12.y1; IMAGE 3400511 | unknown |

| Xl.2213.1.A1_at | −3.311 | BG022871 | UniGene Xl.2213; suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (Socs3) | signaling |

| Xl.4337.1.A1_at | −3.215 | BC097548 | Xenopus laevis hypothetical protein MGC114680 | unknown |

| Xl.15435.1.A1_at | −3.185 | BJ081509 | UniGene Xl.79199; Fin and gill-specific type-1 keratin (fgk) | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.16561.1.A1_at | −3.135 | CF521493 | EST: AGENCOURT_15529711; IMAGE 7010138 | unknown |

| Xl.16590.1.S1_at | −3.115 | BJ049628 | UniGene Xl.63625; Glucocorticoid induced transcript 1 (glcci1) | unknown |

| Xl.23897.1.S1_at | −2.994 | BC068675 | Cornifelin gene1 (Cnfn1-a) | unknown |

| Xl.7794.1.A1_at | −2.833 | BQ897357 | EST: AGENCOURT_8670989; most similar to Xenopus tropicalis ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (ralgds) | signaling |

| Xl.2209.1.S1_at | −2.695 | CB562491 | UniGene Xl.55075, complement component 3 (c3) | signaling |

| Xl.1064.1.S1_at | −2.695 | U63818.1 | Ring finger protein | transcription |

| Xl.13604.1.A1_at | −2.646 | BJ088530 | EST: BJ088530; most similar to Xenopus laevis IMAGE clone 4965486 | unknown |

| Xl.23980.1.A1_at | −2.618 | AW764542 | EST: da88e01.x1 | unknown |

| Xl.2443.1.S1_at | −2.604 | BC046660.1 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 1 (Dnaja4.2) | protein folding |

| Xl.9975.1.A1_at | −2.597 | BJ088036 | EST: BJ088036; most similar to ras homolog family member T1 (rhot1) | signaling |

| Xl.23110.1.A1_at | −2.584 | BJ076210 | UniGene Xl.83926; Regulator of calcineurin 1 (rcan1) | signaling |

| Xl.22434.1.A1_at | −2.525 | CB560725 | UniGene Xl.22434; N-acetylgalactosaminidase alpha (naga-a) | metabolism |

| Xl.2361.1.A1_at | −2.475 | BQ399921 | UniGene Xl.2361; phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 5 (pik3r5) | metabolism |

| Xl.16796.1.S1_at | −2.463 | BJ085230 | EST: BJ085230; most similar to Xenopus tropicalis Rab interacting lysosomal protein-like 1 (rilpl1) | protein transport |

| Xl.166.1.S1_at | −2.439 | U66003.1 | Adam13 | proteolysis |

| Xl.15263.1.A1_at | −2.421 | BQ400687 | UniGene Xl.63771; predicted sickle tail protein like (etl4) | unknown |

| Xl.16177.1.A1_at | −2.421 | BJ055605 | UniGene Xl.16177; Axin 2 (Axis inhibition protein 2) | signaling |

| Xl.16447.1.A1_at | −2.387 | BE505669 | UniGene Xl.16447; strongly similar to mouse CDC42 small effector protein 2 (cdc42ep2) | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.15778.1.A1_at | −2.370 | BJ056356 | EST: BJ056356 | unknown |

| Xl.2755.1.S1_at | −2.336 | AY062263.1 | Sp1-like zinc-finger protein (XSPR-2) | transcription |

| Xl.541.1.S1_s_at | −2.315 | BC041183.1 | jun oncogene | transcription |

| Xl.11153.1.A1_at | −2.288 | BJ057396 | EST: BJ057396; most similar to Xenopus tropicalis clone ISB1-168-L6 | unknown |

| Xl.23887.1.A1_at | −2.283 | BJ090458 | UniGene Xl.23887; Rab40B | signaling |

| Xl.738.1.S1_at | −2.268 | AF317656.1 | Akt | signaling |

| Xl.15014.1.A1_at | −2.262 | BJ048100 | EST: BJ048100 | unknown |

| Xl.15701.1.S1_at | −2.247 | AY150813.1 | Kremen2 (krm2) | signaling |

| Xl.25379.1.A1_at | −2.242 | BM262157 | UniGene Xl.25379; weakly similar to meteorin-like protein-like (metrn) | unknown |

| Xl.15834.1.S1_at | −2.222 | BJ050466 | UniGene Xl.63885; Xenopus laevis MGC84728 protein, most similar to similar to mouse/human prohibitin 2 (phb2) | transcription |

| Xl.13799.1.A1_at | −2.217 | BJ085895 | EST: BJ085895 | unknown |

| Xl.16517.1.A1_at | −2.217 | AW199946 | UniGene Xl.16517; zinc finger protein 830 | cell cycle |

| Xl.8910.1.S1_at | −2.212 | BC042269.1 | Keratin type I cytoskeletal 18-A (krt18-a) | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.13511.1.A1_at | −2.203 | BJ085865 | EST: BJ085865 | unknown |

| Xl.2612.1.A1_at | −2.188 | BJ097651 | UniGene Xl.2612; A-kinase anchor protein 2 (akap2) | cytoskeleton |

| Xl.13965.1.A1_at | −2.179 | BJ081606 | UniGene Xl.4228; Adaptor-related protein complex 4, mu 1 subunit (ap4m1) | protein transport |

| Xl.11640.1.A1_at | −2.169 | BJ075244 | UniGene Xl.78983; strongly similar to related RAS viral (rras2) oncogene homolog | signaling |

| Xl.2784.1.S1_at | −2.159 | M96729.1 | Metallothionein (mti) | metabolism |

| Xl.17176.1.A1_at | −2.141 | BM261509 | EST: dai45d06.x1 | unknown |

| Xl.1085.1.S1_at | −2.132 | U57453.1 | Zic2 | transcription |

| Xl.11033.1.A1_at | −2.114 | BM191782 | UniGene Xl.75442; phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class C (pigc) | metabolism |

| Xl.4175.2.A1_at | −2.101 | BJ081456 | EST: BJ081456 | unknown |

| Xl.15853.1.A1_at | −2.062 | BJ089315 | UniGene Xl.15853; strongly similar to Xenopus tropicalis von Willebrand factor C domain-containing protein 2-like, gene 2 precursor (vwc2l) | signaling |

| Xl.15479.1.A1_at | −2.062 | CD328587 | UniGene Xl.15479; Xenopus laevis uncharacterized protein MGC116516; weakly similar to mouse/human mitogen-activated protein kinase 12 (mpk12) | cell cycle |

| Xl.25273.1.A1_x_at | −2.058 | AW782822 | UniGene Xl.25885; weakly similar to Xenopus laevis zinc finger protein 33A | unknown |

| Xl.3057.2.S1_at | −2.053 | BU901475 | UniGene Xl.3057; Xenopus laevis uncharacterized protein LOC100158313; weakly similar to human ZYX gene product | unknown |

| Xl.9994.1.S1_s_at | −2.028 | BC043990.1 | Hypothetical protein MGC64520; strongly similar to Xenopus laevis growth associated protein 43 (gap43-b) | cell adhesion |

| Xl.24413.1.S1_at | −2.020 | BQ397907 | UniGene Xl.24413; moderately similar to Xenopus tropicalis acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3a precursor | metabolism |

| Xl.428.1.S1_at | −2.012 | X64762.1 | HNF1 homeobox A (hnf1a-a) | transcription |

| Xl.13762.1.A1_at | −2.012 | BJ085361 | EST: BJ085361 | unknown |

| Xl.15997.1.A1_at | −2.008 | BJ043804 | UniGene Xl.15997; synaptotagmin-like 1 (sytl1) | protein transport |

| Xl.22640.1.A1_at | −2.008 | BJ086587 | UniGene Xl.22640; Vps20-associated 1 homolog (vta1) | protein transport |

| Xl.19274.1.S1_at | −2.004 | BI442114 | UniGene Xl.19274; Tumor suppressor candidate 3 (tusc3) | ion transport |

To assess the validity of the microarray results, we performed several experiments. First, we measured the expression of five down-regulated genes by qPCR; 3/5 were expressed at lower levels in Six1-injected ACs compared to uninjected control ACs, one of which reached statistical significance (Table 3). Second, we knocked-down endogenous Six1 in whole embryos by injecting morpholino antisense oligonucleotides; this altered the expression patterns of 10/15 down-regulated candidates (Table 6). The expression domains of two were expanded (e.g., IMAGE 3399268), whereas the remainders were reduced (e.g., Cnfn1-a, Snail1; Figure 2). Third, we increased Six1 expression: 15/15 down-regulated candidates had diminished expression domains by injection of mRNAs encoding either wild-type Six1 or the repressive EnR-Six1 construct, and only 4/15 by the activating Six1-VP16 construct (Table 6). Figure 2 shows examples: reduced somite (IMAGE 3399268) and neural crest/placode (IMAGE 4057931) expression by wild-type Six1; reduced PPR (IMAGE 4057931) and neural tube (Zic2, Otx1) expression by EnR-Six1. Interestingly, Zic2 neural tube expression was expanded by Six1-VP16 (87.5%, n=17; Figure 2). Thus, many of the down-regulated genes identified by the microarray assay are likely downstream of Six1 based on published function in Xenopus, chick or mouse, published expression patterns and/or changes in expression after Six1 loss- and gain-of-function. However, Six1 ChIP analyses are required to confirm if any of these candidates are direct transcriptional targets.

Table 6.

Percentage of embryos showing altered expression domains of down-regulated genes in response to changes in Six1 activity

| Candidate | Diminished (↓) or expanded (↑) by Six1 MO knock-down (n) | Diminished by wild-type Six1 (n) | Diminished by Repressive EnR-Six1 (n) | Diminished by Activating Six1-VP16 (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMAGE 4174145 | 0.0 (12) | 66.7 (21) | 92.9 (14) | 0.0 (16) |

| IMAGE 3399268 | 70.0 (10) ↑ | 82.6 (46) | 91.7 (12) | 0.0 (14) |

| IMAGE 4057931 | 20.0 (10) ↓ | 73.0 (37) | 100.0 (13) | 0.0 (16) |

| IMAGE 3400511 | 70.0 (10) ↓ | 59.4 (32) | 88.2 (17) | 0.0 (10) |

| Socs3/BG022871 | 0.0 (15) | 58.5 (41) | 100.0 (15) | 0.0 (5) |

| MGC114680 | 0.0 (14) | 37.8 (37) | 100.0 (12) | 17.6 (17) |

| IMAGE 7010138 | 0.0 (11) | 40.0 (45) | 87.5 (16) | 0.0 (21) |

| Cnfn.1a/BC068675 | 75.6 (14) ↓ | 50.0 (26) | 83.3 (12) | 0.0 (17) |

| Ralgds/BQ897357 | 42.9 (14) ↓ | 50.0 (16) | 88.9 (9) | 14.3 (14) |

| Dnaja4.2/BC046660.1 | 50.0 (14) ↓ | 45.0 (20) | 86.7 (15) | 5.9 (17) |

| Otx1 | 11.8 (17) ↓ | 73.3 (15) | 77.8 (9) | 5.9 (17) |

| Snail1 | 78.6 (14)↓ | 84.2 (19) | 83.3 (15) | 0.0 (10) |

| Foxi1 (Xema) | 71.4 (14) ↓ | 61.1 (18) | 90.9 (11) | 0.0 (16) |

| HoxA1 | 0.0 (14) | nd | 80.0 (15) | 0.0 (16) |

| Zic2 | 42.9% (14) ↑ | nd | 80.0 (5) | 0.0 (17) |

Legend: nd, not done

Expression patterns of uncharacterized genes

The data above suggest that many of the genes whose expression patterns are altered by Six1 are likely to be involved in Six1-related developmental processes. Since a large number of these genes are of unknown function (Figure 1) and/or their developmental expression patterns have not been reported in Xenopus, we randomly picked 10 genes of unknown function up-regulated >2-fold (highlighted in Table 1) and 10 genes of unknown function down-regulated >2-fold (highlighted in Table 5) and performed expression analyses. We also chose a few uncharacterized >1.6 fold altered genes to analyze, and provide more detail for a few characterized genes (shaded in Tables 1, 2 and 5).

RT-PCR

To demonstrate expression levels over time, RT-PCR was performed for 12 of the up-regulated genes (Figure 3A). Nrp1 is strongly expressed maternally, is reduced at blastula stages, strongly expressed during neural ectoderm/neural plate stages, and is reduced at tail bud stages. Arrb2 is expressed at very low levels until late tail bud stages. BG022063 and LOC10003704 are expressed at low levels prior to gastrulation, are highly expressed from neural plate through tail bud stages, after which expression decreases. BQ399495 is strongly expressed from cleavage through gastrulation stages, followed by peaks at early and late tail bud stages. Hrpt1 is highly expressed at cleavage and blastula stags, followed by reduced expression through the remaining stages. LOC414689 is weakly detected at all stages, but more highly at neural tube through tail bud stages. Uncx4.1 is strongly expressed nearly uniformly across all stages. Xxylt1 is highly expressed at cleavage and blastula stages, decreasing at neural plate stages, and peaking again at late tail bud stages. Ism1 is expressed nearly uniformly across all developmental stages, Arnt is strongly expressed from early neural plate to late tail bud stages and Hox3A is highly expressed maternally, then uniformly at lower levels from gastrula through early tail bud, then at increased levels at later tail bud stages.

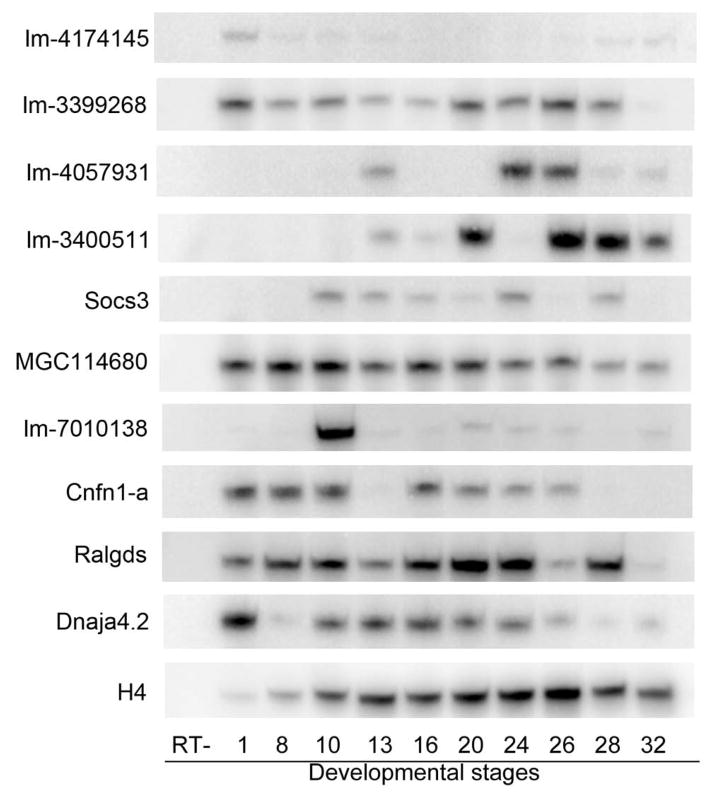

Figure 3.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR assays illustrate the temporal expression patterns of previously uncharacterized up-regulated (A) and down-regulated (B) genes in normal, unmanipulated Xenopus embryos. RT-, minus RT step; numbers across the bottom indicate the developmental stages. H4 is an internal control. Im, IMAGE

RT-PCR was performed for 10 of the down-regulated genes (Figure 3B). IMAGE 4174145 is weakly expressed at all stages. IMAGE 3399268 is moderately expressed at all stages. IMAGE 4057931 is detected at early neural plate and early tail bud stages. IMAGE 3400511 is weakly expressed until early neural plate and late tail bud stages. Socs3 is weakly expressed from gastrulation through tail bud stages. MGC114680 and Ralgds are expressed at uniform levels from cleavage through tail bud stages, with less expression at later stages. IMAGE 7010138 is highly expressed at gastrulation and expressed at low levels after that (but see tissue expression patterns below). Cnfn1-a is highly expressed at cleavage to gastrulation stages, and again at late neural plate through early tail bud stages. Dnaja4.2 is strongly expressed at cleavage stages and then moderately expressed from gastrula though tail bud stages.

These temporal expression profiles partially overlap with that of Xenopus Six1. Six1 expression is not detected by RT-PCR or in situ hybridization at cleavage or blastula stages (Pandur and Moody, 2000). This indicates that during these early stages Six1 does not regulate the expression of the up-regulated or the down-regulated genes. However, Six1 expression is detected by RT-PCR at gastrula (st 10.5), neural plate (st 12), neural tube (st 19), tail bud (st 26/27) and larval (st 37/38; st 40) stages when placodes, somites, and kidney anlage form (Pandur and Moody, 2000). This partial overlap with the RT-PCR data for each of the tested genes (Figure 3) is consistent with the possibility that Six1 may regulate these genes after the onset of gastrulation.

In situ expression of up-regulated genes

To demonstrate spatial expression patterns, whole embryo in situ hybridization (ISH) analyses were performed for 14 up-regulated genes for which no ISH data are available, and for 5 up-regulated genes for which the data are incomplete (Nrp1, Pbx1b, Ism1, Arnt, HoxA3). At the early developmental stages, all 19 genes share very similar expression patterns (Figures 4–6, Table 7). All are expressed maternally, with enhanced localization to the animal hemisphere at cleavage stages (Figure 4). To be assured that this was not due to lack of probe penetration into the yolky vegetal cells, we also bisected embryos prior to ISH; enhanced animal hemisphere expression and lack of vegetal expression was consistently observed (Figure 7). At blastula stages, expression remained in the animal half of the embryo (Figure 4), in some cases extending into the equatorial region (Table 7; Figure 8). At gastrula stages, all genes but Ism1 are diffusely expressed throughout the ectoderm germ layer; as previously reported (Pera et al., 2002), Ism1 instead is expressed in the ventrolateral portion of the blastopore lip of the gastrula (Table 7). Some genes had enhanced expression in the animal pole ectoderm (Nrp1, Arrb2, LOC100037047, Uncx4.1); sectioning the embryos showed that others also had weak expression in the involuting mesoderm (Hprt1, Xxylt1, Trhd, Pbx1b, Nfya, Arnt, Tbc1d31, HoxA3, Cdca7l, Papd4) (Figures 4, 8; Table 7). To be assured that the diffuse staining at these early stages was not the result of non-specific background, embryos also were processed with sense directed RNA probes; very little background was detected (Figure 9).

Figure 4.

Whole mount in situ hybridization assays at early developmental stages illustrating the common expression patterns of 14 up-regulated genes. A: Nrp1, Arrb2, BG022063, LOC100037047, BQ399495, Hrpt1, Rbm42-6. B: LOC414689, Uncx4.1, Xxylt1, Nfya, Tbc1d31, Cdca7l, Papd4-a. For all genes, expression is enhanced in the animal cells (an) of cleavage and blastula embryos (side views). At gastrula stages, expression is throughout the ectoderm, occasionally enhanced in the animal cells (e.g., Arrb2) or the dorsal cells (e.g., Nrp1) (side views). At early neural plate stages, all genes are expressed in the epidermis (epi), often more intensely on the dorsal (d) side, including neural plate (np) and border zone (bz) (all except Nrp1 are side views with anterior [a] to the left; Nrp1 is an anterior view with dorsal to the top). At late neural plate and neural tube stages, expression is strongest in the neural crest (nc), preplacodal region (ppr), neural tube (nt) and occasionally cement gland (cem) (all are anterior views). For Nrp1, embryos were sectioned in the horizontal plane to demonstrate that the ppr stripe in the whole embryo is due to expression in the deep (d) layer of the ectoderm, not the superficial (s) layer of the ectoderm or the pharyngeal endoderm (phe); ph, lumen of pharynx.

Figure 6.

Whole mount in situ hybridization assays illustrating the expression patterns of previously characterized genes up-regulated (Trhd-a, Pbx1b, Ism1, Arnt, HoxA3) or down-regulated (Foxi1-Xema) genes at stages previously unpublished. Abbreviations are as in Figures 4 and 5.

Table 7.

Developmental expression patterns of up-regulated genes

| Gene title/accession # OB Clone # | Cleavage | Blastula st 8–9 |

Gastrula st 10–11.5 |

Neural Plate E: st 12–13 L: st 14–17 |

Neural tube closure st 18–22 |

Tail bud st 23–31 |

Larva st 32–38 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nrp1/BQ400635 4969039 |

animal | AC | animal ecto, dorsal ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi, stripe in midbrain, noto |

1. spcd, NC, PPR | 1. spcd, NC, PPR, dorsal gut; Hb, ret, olf, lens, oto, dorsal epi, epibranchial placodes, cem, BA, nephric meso | same, plus pineal, spcd, IX/Xg, BA-distal patches, heart |

| Arrb2/BG812762 4740312 |

animal | AC | animal ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi, cem, dorsal meso |

NT, NC, dorsal epi, cem, somites | Hb, ret, oto, BA, somites | same, plus dorsal spcd, lens, head epi, nephric meso |

|

BG022063 3749434 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi, dorsal meso |

NT, NC, olf, lens, oto, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

| LOC100037047/BG885936 3437507 |

animal | AC | animal ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, head epi, cem, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, cem, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

|

BQ399495 4965752 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, oto, BA, somites | same, plus lens, nephric meso, heart |

| Hprt1/BG023545 5047264 |

animal | AC, eq | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, noto, somites | brain, ret, stripe in Mb, lens, oto, head epi, BA | same, plus nephric meso |

| Rbm42-b/BJ083747 6635289 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, head epi, BA, somites | same, plus cranial ganglia, nephric meso |

| LOC414689/BQ398913 6636835 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi, dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, head epi, cem, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, head epi, cem, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso, heart |

| Uncx4.1/BC044278.1 5543082 |

animal, eq | AC, eq | animal ecto | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT-lat stripes in Mb, Hb and spcd, NC, olf, head epi, somites, nephric meso | brain, ret, spcd, olf, oto, head epi, BA, somites, nephric meso | same, plus lens |

| Xxylt1/BQ386473 6639045 |

animal | AC, eq | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso, heart |

| Trhd-a/AY099224 | 2. present* | AC, eq | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, oto, epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso, pharyngeal pouches |

| Pbx1b/AF480430.1 | animal | AC, eq | ecto, meso |

3. NP, BZ dorsal meso |

3. brain, ret, ant spcd, BA somites |

3. same, plus nephric meso, lateral plate meso olf, lens, oto, somites |

|

| Ism1/BJ078437 4888159 |

4. animal | AC | 4. ventro-lateral blastopore lip |

4. E: same, plus noto 4. L: ant NP, BZ pharyngeal endoderm |

4. Mb, post spcd, NC, Dlp, paraxial meso | 4: Di, Mb, oto, BA, tailbud, ventral blood islands | same, plus somites |

| Nfya/NM_0-01090739.1 6631251 |

5. present* animal |

AC | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, olf, lens, oto, somites | brain, ret, ant spcd, olf, lens, oto, BA, somites, nephric meso | same |

| Arnt/AY036894.1 4203590 |

6. animal | 6. AC | 6. animal ecto, meso | 6. NP, BZ, epi, dorsal meso | NT, NC, PPR, epi, somites |

6. brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, BA, somite, nephric meso olf, cranial ganglia |

9. same |

| Tbc1d31/BC077576 5079674 |

animal | AC | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, diffuse epi, BA, noto, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

| HoxA3/BC041731.1 4683538 |

animal, weak | AC | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites |

7. spcd, caudal BAs, somites Strong stripe in Hb |

same |

| Cdca7l/BC126014 6864704 |

animal | AC | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, epi, somites | same, plus scattered epi cells, BA, nephric meso |

| Papd4/MGC83633 5084876 | 8. present* animal | AC | ecto, meso | E: dorsal ecto, epi L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

ISH expression patterns at different developmental stages for 14 genes for which there are no ISH expression data. ISH patterns also were completed for 5 genes for which there are available descriptions. For 3 genes (Trhd-a, Nfya, Papd4) presence of expression (*) was detected only by Northern blot, RNase protection, RT-PCR or RNA-Seq.

Abbreviations: AC, animal cap; BA, branchial arches; BZ, border zone; cem, cement gland; dlp, dorso-lateral placode; E, early; ecto, ectoderm; epi, epidermis; eq, equatorial; Hb, hindbrain; IX/Xg, glossopharyngeal/vagal ganglion; L, late; Mb, midbrain; meso, mesoderm; NC, neural crest; NP, neural plate; NT, neural tube; OB, Open Biosystems; olf, olfactory placode; oto, otocyst; PPR, pre-placodal region; ret, retina; spcd, spinal cord; st, stage; Vg, trigeminal ganglion; VIIg, facial ganglion.

Figure 7.

Four examples of cleavage stage gene expression in embryos that were bisected prior to the in situ hybridization protocol to facilitate probe access to all of the cells. In each case the probe was detected in the animal pole blastomeres (a) and in marginal zone animal blastomeres (arrows), but not in vegetal blastomeres (v).

Figure 8.

Examples of embryos bisected after the in situ hybridization protocol to reveal expression patterns in internal cells. BQ399495: At blastula (left image, sagittal section), expression is primarily in the animal cap (AC) cells, and barely detected in the equatorial (eq) zone. At neural plate stages (right image, transverse section), expression is observed in the neural plate (np), somites (so) and epidermis (epi). Hprt1: At blastula (left image, sagittal section), expression is in both animal cap and equatorial cells. At gastrula stages (right image, sagittal section, anterior to the left), expression is observed in the surface ectoderm (ecto) and involuting mesoderm (meso); bl, dorsal blastoporal lip. Xxylt1: At blastula (left image, sagittal section), expression is in both animal cap and equatorial cells. At neural plate stages (right image, sagittal section, anterior to the left), expression is observed in the neural plate and underlying dorsal mesoderm (meso). IMAGE 3399268: At blastula (left image, sagittal section), expression is in both animal cap and equatorial cells. At gastrula stages (right image, sagittal section, anterior to the left), expression is observed in the animal ectoderm, but barely detected in the involuting mesoderm. Cnfn1-a: At gastrula stages (sagittal section, anterior to the left), expression is observed in the animal ectoderm, but not in the involuting mesoderm. IMAGE 7010138: At blastula (left image, sagittal section), expression is primarily in the animal cap cells, and barely detected in the equatorial zone. At gastrula stages (middle image, sagittal section, anterior to the left), there is strong expression in both the ectoderm and involuting mesoderm. At neural plate stages (right image, sagittal section, anterior to the left), weak expression is observed in both the neural plate and underlying dorsal mesoderm.

Figure 9.

Examples of Xenopus embryos hybridized with sense RNA probes to evaluate the extent of non-specific staining at the early stages when expression patterns are diffuse (cf. Figures 4, 5, 6, 10).

At neural plate stages all 19 genes are expressed in the ectoderm/epidermis, with enhanced expression on the dorsal side of the embryo, including the early neural plate and neural border zone (BZ); for nearly all of these genes sectioning the embryos also showed expression in the dorsal mesoderm (Table 7; Figure 8). At early neural plate stages Arrb2 is additionally expressed in the cement gland, and Ism1 in the pharyngeal endoderm. At neural tube closure stages, all 19 genes are expressed in the neural tube and neural crest; 15/19 genes are additionally expressed in the PPR or a subset of cranial placodes. At later tail bud and larval stages, expression patterns diverge (Figure 5, Table 7). However, each of the 19 genes is expressed in at least two tissues whose development is known to be regulated by Six1: at least one placode-derived structure (17/19), somite (18/19) or nephric mesoderm (17/19); the latter is consistent with a potential role in the BOR kidney deficit. Of those with placode expression, 17/17 are expressed in the otocyst, consistent with a potential role in the BOS3 hearing deficit. Although Six1 is thought to be primarily important in placode development, recent work also shows it is required for some neural crest derivatives (Yajima et al., 2014; Garcez et al., 2014); consistent with these reports we find that all 19 of the up-regulated genes are detected in the cranial neural crest and the branchial arch mesoderm. However, it should be noted that many of the 19 genes also have prominent expression in tissues that do not have detectable levels of Six1 at these developmental stages: neural tube/retina (19/19), heart (4/19), cement gland (3/19), pharyngeal endoderm/pouches (2/19), and blood islands (1/19). Therefore, additional transcriptional pathways must regulate these genes in these additional tissues.

Figure 5.

Whole mount in situ hybridization assays at tail bud to larval stages illustrating more divergent expression patterns of 14 up-regulated genes. A: Nrp1, Arrb2, BG022063, LOC100037047, BQ399495. B: Hrpt1, Rbm42-6, LOC414689, Uncx4.1, Xxylt1. C: Nfya, Tbc1d31, Cdca7l, Papd4-a. Side views at tail bud (left column) and larval (middle column) stages, with anterior to the left and dorsal to the top, and transverse sections at larval stages (right side) with dorsal to the top. Abbreviations: ba, branchial arches; cem, cement gland; ep, epibranchial placodes; epi, epidermis; fb, forebrain; h, heart; hb, hindbrain; IX/Xg, glossopharyngeal/vagal ganglion; l, lens; mb, midbrain; ne, nephric mesoderm; olf, olfactory placode; oto, otocyst; p, pineal; r, retina; spcd, spinal cord; so, somites; Vg, trigeminal ganglion; VIIg, facial ganglion.

Because the expression patterns of five of the genes identified in the microarray analysis were previously published, but not for all stages of development, we completed their developmental expression patterns (Figures 4–6, Table 7). Of note, Nrp1, a receptor for Sema3a, is expressed in the deep layer of the PPR (Figure 4A) and in several placodes including otic (Figure 5A). Trhda is a maternally-expressed nuclear protein that inhibits neural differentiation (Wu et al., 2001); since no ISH data are available we present the entire developmental series (Figure 6). Pbx1, a homeobox-containing transcription factor that interacts with Meis and Hox proteins to influence hindbrain and neural crest gene expression (Maeda et al., 2002), is additionally expressed in the animal ectoderm, some placodes and somites (Figure 6). Ism1 is a novel secreted factor co-expressed in FGF8-expressing domains (Pera et al., 2002); we found that in addition to the published expression pattern it is expressed in the pharyngeal endoderm and somites (Figure 6). Arnt is a bHLH/PAS factor that regulates many aspects of vertebrate development and tumorigenesis (Crews and Fan, 1999; Labrecque et al., 2013); we found that in addition to the published expression pattern (Bollerot et al., 2001), it is expressed in the neural plate, neural crest, PPR, olfactory placode, cranial ganglia and somites (Figure 6, Table 7). HoxA3 is a homeodomain transcription factor involved in axis and craniofacial patterning (Quinonez and Innis, 2014); we found that in addition to the expression pattern posted on Xenbase (http://www.xenbase.org/gene/showgene.do?method=display&geneId=482266&) it is expressed in a pattern very similar to the other up-regulated genes prior to neural tube closure, but is not subsequently expressed in the placodes (Figure 6, Table 7).

In situ expression of down-regulated genes

ISH analyses were performed for 10 down-regulated genes for which there are no ISH data available, and for 1 gene for which the data are incomplete (Foxi1/Xema) (Figures 6, 10–11, Table 8). At the early developmental stages, the 10 uncharacterized genes share very similar expression patterns with each other and with the up-regulated genes. All are expressed maternally, with enhanced localization to the animal hemisphere at cleavage and blastula stages (Figure 10); this localization was not due to poor probe penetration (Figure 7). At blastula stages, expression remained in the animal half of the embryo (Figure 10), in some cases extending into the equatorial region (Table 8; Figure 8). At gastrula stages, all 10 genes are expressed throughout the ectoderm; sectioning the embryos showed that a few also had weak expression in the involuting mesoderm (IMAGE 4057931, IMAGE 7010138, Ralgds, Dnaja4.2) (Table 8, Figure 8). The diffuse staining at early stages was not the result of non-specific background, as demonstrated by processing embryos with sense directed RNA probes (Figure 9).

Figure 10.

Whole mount in situ hybridization assays at early stages illustrating common expression patterns of 10 down-regulated genes. A: IMAGE 4174145, IMAGE 3399268, IMAGE 4057931, IMAGE 3400511, Socs3. B: MGC 114680, IMAGE 7010138, Cnfn1-a, Ralgds, Dnaja4.2. For all genes, expression is enhanced in the animal cells (an) of cleavage and blastula embryos, and is throughout the ectoderm at gastrula stages (side views). At early neural plate stages, all genes are expressed in the epidermis (epi), often more intensely on the dorsal (d) side, including neural plate (np) and border zone (bz) (all except IMAGE 3400511 are side views with anterior [a] to the left; IMAGE 3400511 is an anterior view). At later neural plate and neural tube stages, expression is strongest in the neural crest (nc), preplacodal region (ppr), neural tube (nt) and epidermis (epi) (anterior views). Cnfn1-a is uniquely expressed in the hatching gland (hg).

Figure 11.

Whole mount in situ hybridization assays at tail bud to larval stages illustrating more divergent expression patterns of 10 down-regulated genes. A: IMAGE 4174145, IMAGE 3399268, IMAGE 4057931, IMAGE 3400511, Socs3. B: MGC 114680, IMAGE 7010138, Cnfn1-a, Ralgds, Dnaja4.2. Side views at tail bud (left column) and larval (middle column) stages, with anterior to the left and dorsal to the top, and transverse sections at larval stages (right side) with dorsal to the top. Abbreviations are as in Figure 10. For Cnfn1-a: hg, hatching gland; clo, cloaca.

Table 8.

Developmental expression patterns of down-regulated genes

| Gene title/ accession # OB # |

Cleavage | Blastula st 8–9 |

Gastrula st 10–11.5 |

Neural Plate E: st 12–13 L: st 14–17 |

Neural tube closure st 18–22 |

Tail bud st 23–31 |

Larva st 32–38 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMAGE 4174145/BC080322 4174145 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, head epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

| IMAGE 3399268/BC079829 3399268 |

animal | AC, eq | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, cranial ganglia, epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

| IMAGE 4057931/BG264797 4057931 |

animal | AC | ecto, weak meso | E: ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, pineal, ret, spcd, lens, oto, BA, somites | same, plus olf, cranial ganglia, nephric meso |

| IMAGE 3400511/BG020210 3400511 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, head epi, BA, somites | same, plus oto, cranial ganglia, heart |

| Socs3/BG022871 4173655 |

animal 1. not detected* |

AC 1. not detected* |

ecto 1. not detected* |

E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso 1. strong expression* |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites 1. strong expression* |

brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, BA, somites 1. strong expression* |

same, plus cranial ganglia, nephric meso 1. strong expression* |

| MGC114680/BC097548 6316942 |

animal | AC | ecto | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, epi, BA, somites | same, plus cranial ganglia, nephric meso |

| IMAGE 7010138/CF521493 7010138 |

animal | AC, eq | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, epi, somites | same, plus BA, nephric meso |

| Cnfn1-a/BC068675 6316571 |

animal 2. present* |

AC 2. present* |

ecto 2. present* |

E: dorsal ecto L: scattered cells in NP and BZ 2. present* |

hatching gland, dorsal epi 2. present* |

hatching gland, cem, scattered cells in epi 2. present* |

same, plus brain, ret, spcd, oto, Vg, BA, somites, nephric meso, ventral pharynx, caudal noto 2. present* |

| Ralgds/BQ897357 4681426 |

animal | AC | ecto, meso | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, olf, lens, oto, cranial ganglia, head epi, BA, somites | same, plus nephric meso |

| Dnaja4.2/BC046660.1 4930076 |

animal | AC | ecto, weak meso | E: dorsal ecto L: NP, BZ, epi dorsal meso |

NT, NC, PPR, dorsal epi, somites | brain, ret, spcd, lens, oto, BA, somites | same, plus olf, cranial ganglia, nephric meso |

| Foxi1 (Xema) | 3. not detected* | 3. AC ecto | 3. antero-ventral ecto | 3. BZ, antero-ventral ecto | 3. antero-ventral ecto | 3. antero-ventral ecto | brain, ret, spcd, oto, cranial ganglia, BA, somites |

ISH expression patterns at different developmental stages for 10 genes for which there are no ISH expression data. ISH pattern also was completed for 1 gene for which there are available descriptions. For 2 genes (Socs3, Cnfn1-a) presence of expression (*) was detected only by Northern blot, RNase protection, RT-PCR or RNA-Seq.

At early neural plate stages ectodermal expression is enhanced on the dorsal side of the embryo, including the early neural plate and BZ. At later neural plate stages all genes are expressed in the epidermis, neural plate, neural crest, PPR, and epidermis, and most were also expressed in the dorsal mesoderm. Cnfn1-a is not detected in the mesoderm (Figure 8), and is uniquely expressed in scattered cells throughout the ectoderm. At neural tube closure stages, 9/10 of the genes are expressed in the neural tube, neural crest, PPR, dorsal epidermis and somites. At neural tube through tail bud stages Cnfn1-a is uniquely expressed in the hatching gland and in the epidermis near the ventral midline and surrounding the cloaca (Figures 10B, 11B). At later tail bud and larval stages, expression patterns diverge (Figure 11, Table 8). However, all 10 genes are expressed in tissues whose development is known to be regulated by Six1, including at least one placode derived structure (10/10), neural crest (9/10), somites (10/10) and nephric mesoderm (8/10). These temporal patterns of expression are mostly congruent with the RT-PCR results (Figure 3B), although in some cases the color reaction was allowed to develop for up to 48 hours due to the low abundance of the transcripts. For example, even though IMAGE 7010138 is mostly detected by RT-PCR only at the onset of gastrulation, it is clearly detectable by ISH at earlier and later stages, albeit, with less chromogenic intensity (Figure 8). Foxi1-Xema is a transcription factor involved in epidermal development (Suri et al., 2005). We found that in addition to tissues previously reported, at larval stages there is expression in neural tube-derived structures, placode-derived otocyst and cranial ganglia, neural crest-derived branchial arches and in somites (Figure 6, Table 8).

One would expect down-regulated genes to be detected in tissues that do not also express Six1. For some stages and tissues, this expectation holds. For example, 11/11 are expressed in the cleavage and blastula precursors of the ectoderm, which do not express Six1 (Pandur and Moody, 2000). In addition, at later stages 11/11 are expressed in the epidermis and neural tube; these results are consistent with gain-of-function studies in chick and frog showing that when Six1 is ectopically expressed it represses genes characteristic of these tissues (reviewed in Grocott et al., 2012; Saint-Jeannet and Moody, 2014). However, inconsistent with this expectation, most of the putative down-regulated genes are also expressed in the PPR, placodes (including otocyst), neural crest, somites, and nephric mesoderm. This overlap with Six1 expression suggests that additional transcriptional pathways upregulate these genes even in the presence of Six1.

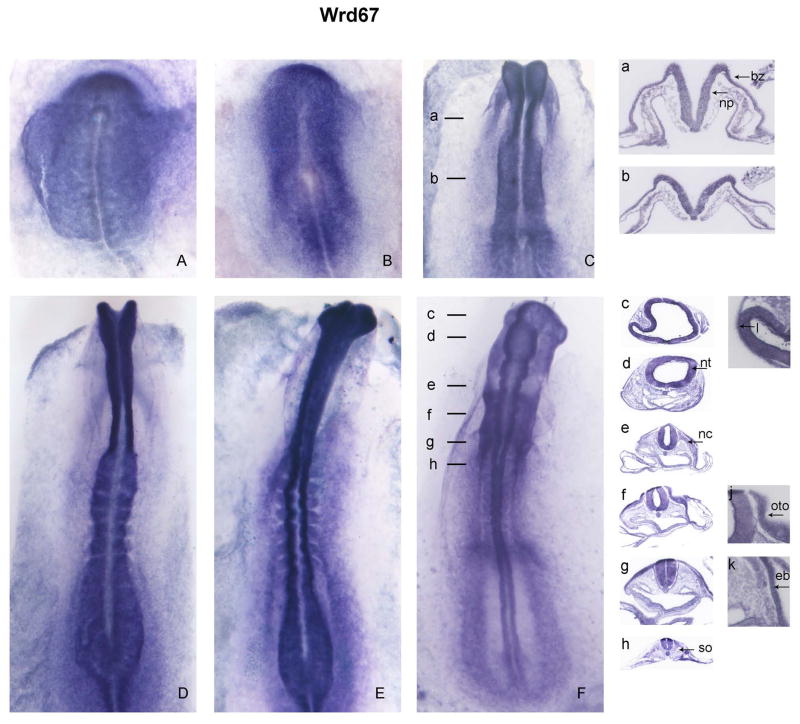

In situ expression of homologous genes in chick

To assess whether the expression of putative Six1 target genes is conserved in amniotes we identified chick homologues using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Out of 19 up-regulated and 17 down-regulated Xenopus transcripts we determined 17 and 11 chick mRNAs with high sequence identity. Of those, we selected five up-regulated genes (Pbx1, Arnt, XXYLT1, WDR67, Nrp1) and one down-regulated gene (DNAJA1) for expression analysis. Except Nrp1, all transcripts show similar expression profiles to their Xenopus homologues (Figures 12–16; Table 9). Nrp1 is not expressed in the ectoderm at any stage investigated, but found in the endoderm underlying the PPR (not shown). In contrast, Pbx1, Arnt, Wrd67 and DNAJA1 are broadly expressed in all three germ layers from primitive streak to 11–14 somite stages. However, their expression is generally enriched in the ectoderm including the future neural plate and PPR, the developing neural tube, neural crest cells and placodal tissue, in particular the otic and epibranchial placodes. Hybridization with sense-directed RNA probes indicates that these diffuse patterns of expression are not the result of non-specific background staining (Figure 17). At neural tube stages Six1 remains expressed in all placodes except for the lens (Sato et al., 2012). Interestingly, Pbx1, Arnt, XXYLT1 and WDR67 are also absent from the lens, whereas DNAJA1, a down-regulated transcript, is present. Unlike the other transcripts, XXYLT1, starts to be expressed in the posterior epiblast and primitive streak at gastrulation stages before being strongly upregulated in the neural plate and forming neural tube. At placodal stages it is present in the otic and epibranchial placodes, neural crest cells and the intermediate and posterior lateral plate mesoderm. Thus, expression patterns of selected genes in chick are generally similar to those observed in Xenopus.

Figure 12.

Whole mount in situ hybridization for Pbx1 from primitive streak to 14-somite stages. Rostral is to the top, caudal to the bottom of the images. Lines in C and E indicate the levels of sections shown in a–h; i–k are higher magnifications of the placode areal shown in c, f and g respectively. bz, border zone; eb, epibranchial placode; l, lens placode; nc, neural crest; np, neural plate; oto, otic placode; so, somite.

Figure 16.

Whole mount in situ hybridization for DNAJA1 from primitive streak to 14-somite stages. Rostral is to the top, caudal to the bottom of the images. Lines in C and E indicate the levels of sections shown in a–h; i–k are higher magnifications of the placode areal shown in c, f and g respectively. Abbreviations are as in Figure 12.

Table 9.

Developmental expression patterns of chick homologous genes

| Gene Symbol/ NCBI gene ID/EST # | HH4 Gastrula | HH5 Head process | HH6/HH7 Neural plate | HH8/9 Neural folds | HH9/HH10 Neural tube | HH11/12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBX1 / 395505/ ChEST643j12 | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm | NP, NC, PPR, mesoderm, endoderm | NP, NC, PPR, somites | NT, NC, otic, epibranchial placodes, notochord, somites, lateral plate mesoderm, endoderm | Mid- and hindbrain, NC, otic, epibranchial placode, notochord, somites, lateral plate mesoderm, endoderm |

| ARNT /374026 / ChEST814a24 | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm | NP, NC, PPR, ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm | NP, NC, PPR, somites, epidermis | NT, NC, otic, epibranchial placodes, epi, notochord, somites, lateral plate mesoderm, endoderm, blood islands | Brain, notochord, NC, otic, epibranchial placode, epi, somites, lateral plate mesoderm, endoderm |

| XXYLT1 / 424896/ ChEST85d22 | Primitive streak, posterior epiblast | NE, BZ | NP, NC | NP, NC, posterior paraxial mesoderm | Fore-, mid- and anterior hindbrain, cranial NC, posterior paraxial mesoderm | Brain, NC, otic, nephric mesoderm, posterior paraxial mesoderm |

| WDR67/ 420349/ ChEST325c2 | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm, posterior epiblast | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm, posterior ectoderm | NP, NC, PPR, head fold | NP, NC, PPR, notochord, mesoderm, endoderm | NT, otic, epibranchial placodes, somites, notochord, mesoderm, endoderm | Brain, NC, lens placode, otic, epibranchial placode, epi somites, notochord, mesoderm, endoderm |

| DNAJA1/427376/ ChEST151p15 | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm, posterior epiblast | NE, BZ, mesoderm, endoderm, posterior ectoderm | NP, NC, PPR, lateral mesoderm, lateral endoderm, posterior ectoderm | NP, NC, PPR, somites, posterior ectoderm | NT, NC, lens placode, otic, epibranchial placode somites, lateral plate mesoderm, paraxial mesoderm, endoderm, blood islands | Brain, NC, lens placode, otic, epibranchial placode somites, lateral plate mesoderm, nephric mesoderm, endoderm, blood islands |

Abbreviations: BZ, border zone; epi, epidermis; HH, Hamburger-Hamilton stage; NC, neural crest; NE, neural ectoderm; NP, neural plate; NT, neural tube; otic, otic placode or vesicle; PPR- Pre-placodal region

Figure 17.

Examples of chick embryos hybridized with sense RNA probes to evaluate the extent of non-specific staining (cf. Figures 12 – 16). A, D, F, I: primitive streak stages. G, head fold stage. B, E, J: 3–4 somite stage. C, 14-somite stage.

Summary

The expression patterns of the genes identified in this study as potential targets of Six1 are consistent with previous reports showing that Six1 plays an important role in the development of vertebrate cranial sensory placodes, somites and kidney. The majority of up-regulated genes are expressed in tissues known to express Six1 (PPR, placodes, somites, nephric mesoderm), which is expected for putative activated targets. However, their expression in Six1-negative tissues, including neural plate, and epidermis, indicates that they also are regulated by additional factors. The down-regulated genes are expressed in Six1-negative tissues, which is expected for putative repressed targets; their expression in some Six1-positive tissues indicates that they also are upregulated by additional factors even in the presence of Six1. Because the majority of the genes described herein are expressed in the developmental precursors of two organs whose defects are diagnostic for BOS and BOR syndromes, the ear and the kidney, they are new candidates for potential involvement in these birth defects.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Frog embryos, animal cap explants and microinjections

Fertilized Xenopus laevis eggs were obtained by either in vitro fertilization (for ACs) or gonadotropin-induced natural mating of adult frogs (for ISH) as described elsewhere (Moody, 2000). mRNAs were synthesized by in vitro transcription (Ambion, mMessage mMachine kit). mRNA encoding wild-type Six1 (400pg) was injected into the animal poles of both cells at the 2-cell stage. ACs were dissected from microinjected embryos and from uninjected siblings (controls) at stages 8.5–9.0, cultured in 1X Modified Barth’s solution and collected when sibling embryos reached stage 16. For assessment of Six1 levels on gene expression in whole embryos, previously characterized Six1-specific morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (Six1 MOs) or mRNAs encoding wild type Six1 (400pg), an activating Six1-VP16 fusion protein (100pg), or a repressive EnR-Six1 fusion protein (100pg) were injected into lateral-animal blastomeres of 16-cell embryos (Brugmann et al., 2004). Embryos for RT-PCR and in situ hybridization (ISH) assays were cultured in 100% Steinberg’s solution through blastula stages and in 50% Steinberg’s solution from blastula through larval stages.

Microarray and Statistical Analyses

Four independent samples of Six1 mRNA-injected ACs were collected. Each sample was derived from one different male and two different females and contained ~100 ACs. For each Six1-expressing sample, a control, uninjected sample from sibling embryos also was collected. All samples were processed in parallel for cDNA labeling and chip hybridization to reduce inter-sample variations. Total RNAs were extracted from ACs with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Integrity of RNA was assessed using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and only samples with an integrity number > 8.0 were used. Total RNAs were labeled and fragmented with the Ovation Biotin RNA Amplification and Labeling System (NuGEN Technologies, Inc.). Briefly, 50ng total RNA was used for first- and second-strand cDNA syntheses. The synthesized cDNAs were amplified, purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen), then labeled and fragmented following the Ovation kit instructions. The labeled cDNAs were purified with the Dye Ex kit (Qiagen).

Chip hybridization and statistical analyses were performed by the NINDS-NIMH Microarray Consortium at The Translational Genomics Research Institute (T-GEN, Tempe, AZ). The Affymetrix GeneChip® Xenopus laevis Genome Array (v1.0) bears 15,503 probe sets representing about 14,400 transcripts. The chips were washed and scanned as recommended by the Ovation Biotin RNA Amplification and Labeling System User Guide (version 1.0). GCOS software was used to determine signal intensities and detection calls for each gene. Five replicates of each sample were analyzed. The average replicate correlation values for the control samples and for the Six1-injected samples each were 0.94, indicating consistency between replicates despite random genetic variance between parental frogs. Using GeneSpring software, all experimental arrays were normalized to their matched control array. Genes were then filtered for at least 2 present calls out of 8 calls. The remaining list was tested for significant changes by ANOVA (p<0.05). The raw and processed data are available (GEO accession number GSE11144).

RT-PCR and qPCR

For RT-PCR analysis, whole, wild type Xenopus embryos were snap-frozen at a series of developmental stages. Total RNA was extracted the with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR within linear ranges was performed as previously described (Yan et al., 2009). Some primer sequences were obtained from published papers, whereas the others were designed with the Primer3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000; Supplemental Table 4). Reverse transcription was performed with 1.0μg of RNA using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Standard PCR amplifications were performed with PCR Supermix (Invitrogen) including 1.0μCi α-[32P]dATP (Amersham) in the reaction mixture. All PCR assays were repeated at least three times with independent samples. Bands were visualized with a Storm 860 phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).