Abstract

Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) is an emerging treatment for heart failure. We have reported that epicardial placement of MSC-sheets generated using temperature-responsive dishes markedly increases donor MSC survival and augments therapeutic effects in an acute myocardial infarction (MI) model, compared to intramyocardial (IM) injection. This study aims to expand this knowledge for the treatment of ischemic cardiomyopathy, which is likely to be more difficult to treat due to mature fibrosis and chronically stressed myocardium. Four weeks after MI, rats underwent either epicardial MSC-sheet placement, IM MSC injection, or sham treatment. At day 28 after treatment, the cell-sheet group showed augmented cardiac function improvement, which was associated with over 11-fold increased donor cell survival at both days 3 and 28 compared to IM injection. Moreover, the cell-sheet group showed improved myocardial repair, in conjunction with amplified upregulation of a group of reparative factors. Furthermore, by comparing with our own previous data, this study highlighted similar dynamics and behavior of epicardially placed MSCs in acute and chronic stages after MI, while the acute-phase myocardium may be more responsive to the stimuli from donor MSCs. These proof-of-concept data encourage further development of the MSC-sheet therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy toward clinical application.

Introduction

Administration of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) has great potential to treat various diseases that are not currently curable, including graft-versus-host disease, neurologic diseases, and so on.1 Since the first clinical trial in 1995, MSCs have been injected into more than 2,000 patients, demonstrating safety and feasibility.2 For the treatment of heart disease, results of more than 10 clinical trials have been reported to date, suggesting encouraging outcome in general.3,4 Although cardiomyogenic differentiation of MSCs may be insignificant in vivo, grafted MSCs are able to secrete a range of biological factors, which help protect, repair, and regenerate the failing myocardium (“paracrine effect”).5,6,7 An important limitation of MSC-based therapy for heart failure, however, is lack of an optimal cell-delivery method. Donor cell retention and survival are extremely poor by any of the current injection methods, limiting the efficacy of the treatment.6,7

Recently, the “cell-sheet” technique (epicardial placement of cell-sheets produced with polymer (poly-N-isopropylacrylamide)-based temperature-responsive dishes) has been proposed as an advanced cell-delivery method.8,9,10,11 We have demonstrated that this method markedly increases initial retention and subsequent existence of donor MSCs in the heart, which resulted in amplified paracrine effects and augmented cardiac function improvement, compared to intramyocardial (IM) injection, in a rat acute myocardial infarction (AMI) model.9 Although AMI is an important target of cell therapy, the requirement of a protracted ex vivo culture period for MSC expansion after bone marrow collection and necessity of heart-exposure for the cell-sheet technique have encouraged us to apply this technique for the treatment of post-myocardial infarction (MI) ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM). Due to recent progress in recanalization therapies, the early mortality after AMI has been markedly reduced; however, the number of patients suffering subsequent ICM has been increasing.12 Current therapies for ICM have insufficient efficacy and/or limited availability,12 and therefore, development of new therapies is a high priority; the MSC-sheet therapy is a potential option. However, it would be more challenging to repair the chronically stressed myocardium and/or surrounding mature fibrotic scars in ICM, compared to AMI.

This study therefore aimed to establish in vivo proof-of-concept data for safety and effect of the MSC-sheet therapy for post-MI ICM. In addition, it is not fully understood how and what to extend different host conditions (ICM versus AMI) affect donor MSC behavior following epicardial placement (i.e., retention, survival, migration, differentiation, and secretion). Differences in responsiveness of the host myocardium to the MSC-therapy (i.e., myocardial repair and changes in cardiac function and morphology) in different conditions (ICM versus AMI) are also uncertain. This study, by comparing with our own previous data in an AMI model using same materials and methods,9 described timing-dependent (ICM versus AMI) effects of MSC-sheet therapy at the molecular, cellular, and organ levels in a systematic manner.

Results

MSC-sheet therapy enhanced cardiac function of ICM more extensively than IM injection

We investigated the therapeutic effect of the MSC-sheet therapy (epicardial placement of syngeneic MSC-sheets; CS group) by evaluating cardiac function and structure, in comparison with IM injection of MSC-suspensions (IM group) and sham-control (Sham group), in a rat ICM model based on left coronary artery ligation. All pretreatment indicators for cardiac performance (at 4 weeks after MI) measured by echocardiography were comparable between groups (Supplementary Table S1). During 4 weeks after treatment, there was no mortality in the CS and Sham groups (n = 11 and n = 10, respectively). In contrast, the IM group showed a 22% mortality (two out of nine rats died speculatively due to arrhythmia or heart failure within 3 days after treatment based on autopsy results). At 28 days after treatment, echocardiography demonstrated that left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in the Sham group was reduced from the pretreatment value, while the CS and IM groups had increased LVEF, with a tendency for a higher increase (statistically not significant) in the CS group (Figure 1a and Supplementary Table S1). This corresponded with reduction of both LV end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions (LVDd and LVDs) in the CS group, compared to the other groups, indicating the effect of MSC-sheet therapy to prevent progression of and recover cardiac dilatation in ICM. Consistently, cardiac catheterization showed the highest developed pressure, max dP/dt, and min dP/dt in the CS group (Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S2). The IM group appeared to improve max and min dP/dt compared to the Sham group, but this was not statistically significant. Therefore, it was collectively confirmed that the MSC-sheet therapy provided superior therapeutic effects for the treatment of ICM, compared to IM injection.

Figure 1.

Augmented improvement of cardiac function by MSC-sheet therapy. (a) Echocardiography showed improved cardiac function and structure in the CS group at day 28 after treatment in a rat ICM model. Data are shown as absolute changes (▵) from each corresponding pretreatment values. See Supplementary Table S1 for more detailed data. (b) Cardiac catheterization showed the greatest cardiac performance in the CS group at day 28 after treatment. See Supplementary Table S2 for more detailed results. N = 8–11 in each group in each point. *P < 0.05 versus Sham, †P < 0.05 versus IM. ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; LVDs, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LVDd, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; pre, pretreatment (28 days after left coronary artery ligation); MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells; post, post-treatment. CS, closed circle; Sham, open square; IM, dotted triangle.

Donor cell survival after MSC-sheet therapy was >11-fold higher compared to IM injection

As an underpinning factor of the enhanced cardiac function improvement by the MSC-sheet therapy compared to IM injection, we observed markedly increased donor cell retention and survival throughout the periods studied. Quantitative PCR for the male specific sry gene (after transplantation of male MSCs into syngeneic female hearts with ICM) showed that the donor cell presence at day 3 was 11-fold higher in the CS group (56.0 ± 7.2%) compared to the IM group (5.0 ± 1.0%; Figure 2a). Afterward, donor cell presence was reduced in both groups; however, day-28 donor cell presence was still 18-fold greater in the CS group (9.1 ± 1.9 versus 0.5 ± 0.2%). This represents that the donor cell survival ratio between days 3 and 28 was higher in the CS group (9.1/56.0 × 100 = 16%) compared to the IM group (0.5/5.0 × 100 = 10%). Of note, day-28 donor cell survival in the CS group was higher than day-3 survival in the IM group.

Figure 2.

Increased donor cell survival by mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC)-sheet therapy. (a) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the male specific sry gene following transplantation of male MSCs into female hearts showed that donor cell survival was increased over 11-fold in the CS group compared to the IM group at both days 3 and 28 after treatment. N = 4–5 in each group, †P < 0.05 versus IM. (b,c) Immunofluorescence showed that donor cells (CM-DiI-labeled; orange) formed cell-clusters in the IM group (b), while most of donor MSCs retained at the heart surface in the CS group (c). White-rectangle areas are higher magnification observations. Representative images from five hearts in each group are presented. cTnT, cardiac troponin T (green). (d) Picrosirius red staining detected progressive fibrosis (dark pink) in the MSC-sheets. Scale bars = 1 mm (b,c), 50 μm in (d).

Immunohistostaining revealed that the numbers of surviving donor MSCs appeared to be larger in the Sheet group than in the IM group at both days 3 and 28, consistent to above quantitative data (Figure 1a). Donor cells (labeled with CM-DiI) in the IM group formed isolated cell-clusters within the myocardium at day 3, with the size decreased by day 28 (Figure 2b). In contrast, the majority of donor cells in the CS group retained on the epicardial heart surface, with little migration into the myocardium, both at days 3 and 28 (Figure 2c). Donor cell retention was similarly found on the infarct and border myocardium at day 3 after placement. Size of the MSC-sheets reduced with time between days 3 and 28, consistent to the quantitative donor cell survival data (Figure 1a). This corresponded with progressive fibrosis within the MSC-sheets (Figure 2d). Donor cell survival at day 28 appeared to be better at the margins of infarct compared to the center of infarct. It is speculated that this may be because of limited blood supply from the heart to the center of infarct.

MSCs did not differentiate to cardiomyocytes or mesenchymal lineages

Although we did not observe donor cells (CM-DiI-labeled) that were also positive for cardiac Troponin T in either CS or IM group in immunohistolabeling studies (Figure 2b,c), there were both host-derived (CM-DiI-/PECAM1+) and donor-derived (CM-DiI+/PECAM1+) endothelial cells within the MSC-sheets at day 3 (Figure 3a,b). This suggests that donor MSCs would have differentiated to endothelial cells, or might be fused with host endothelial cells. Sprouting vessels from the myocardium to the MSC-sheets, probably feeding the MSC-sheets, were also found as early as at day 3 (Figure 3a). These vascular formations in the MSC-sheets were, however, limited to the adjunctive areas to the heart; there was no vascular formation in the middle or outer layers of the MSC-sheets. At day 28, both donor-derived and host-derived vasculatures remained detectable in the similar close-to-the-heart areas of the MSC-sheets (Figure 3c). Differentiation of MSCs to mesenchymal lineages in the heart is a possible concern associated with MSC-therapy.13 However, histological studies excluded this complication in both CS and IM groups in our study; no differentiation of donor MSCs to adipocytes or osteocytes was observed (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Endothelial differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in MSC-sheets in vivo. (a) Immunohistostaining showed that there were PECAM1+ vessels (green) connecting the heart and the MSC-sheet (orange) at day 3 after epicardial placement (blue arrows). (b) MSC-sheets contained both CM-DiI+ (orange)/PECAM1+ (green) endothelial cells (donor-derived; white arrows) as well as CM-DiI− (nonorange)/PECAM1+ (green) endothelial cells (host-derived; blue arrows) at day 3. (b) Higher-magnification image of the white-rectangle area in a. (c) At day 28 after treatment, there remained both CM-DiI+ (orange)/PECAM1+ (green) endothelial cells (white arrows) and CM-DiI− (nonorange)/PECAM1+ (green) endothelial cells (blue arrows) in the MSC-sheets. Scale bars = 100 µm (a,c), 50 mm in (b).

MSC-sheet therapy developed enhanced myocardial repair compared to IM injection

Histological studies detected myocardial repair in ICM-hearts by the MSC-sheet therapy. At day 28 after treatment, picrosirius red staining showed that pathological extracellular collagen deposition observed in the Sham group was significantly attenuated widely in both border and remote areas in the CS group (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure S2a). Collagen fraction in the remote area was reduced in the Sheet group compared to the IM group, with a reducing tendency for the Sheet group in the border area. Additional histological assessments demonstrated that infarct size, wall thickness of the infarct, and the amount and constitution of collagen deposition in the infarct were all similar among the groups (Supplementary Figure S3a–d). Isolectin B4 staining showed that the capillary density was increased in both border and remote areas in the CS group compared to the Sham group (Figure 4b and Supplementary Figure S2b). Increased capillary density in the IM group compared to the Sham group did not reach the statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Enhanced myocardial repair (paracrine effects) by mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-sheet therapy. (a) Collagen volume fraction at day 28 after treatment, assessed by picrosirius red staining, was reduced in both border (peri-infarct) and remote areas in the CS group compared to the Sham group (see Supplementary Figure S2a for representative images). (b) Isolectin B4 staining detected increased capillary density at day 28 after treatment in both border (peri-infarct) and remote areas in the CS group (see Supplementary Figure S2b for representative micrographs). (c,d) Immunohistostaining showed that accumulation of (c) CD163+ cells and (d) CD86+ cells in the border areas at day 3 after treatment were increased in the CS and IM groups, respectively (see Supplementary Figure S4a,b for representative micrographs). (e) Quantitative RT-PCR detected myocardial upregulation of a group of genes possibly underpinning MSC-mediated myocardial repair at day 3 after treatment in the CS groups. N = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus Sham, †P < 0.05 versus IM. RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

A role of cardiac macrophages, particularly the alternatively activated M2 phenotype that is known to suppress inflammation and promote tissue healing, to contribute to cell therapy-mediated post-MI myocardial repair has been suggested.14,15 Consistent with this, immunohistolabeling showed that the number of CD163+ M2 “reparative” macrophages was increased in the CS group (Figure 4c and Supplementary Figure S4a). The IM group also had a weak tendency for increased CD163+ cells (statistically not significant), while this was associated with increased CD86+ proinflammatory (M1) macrophages compared to other groups (Figure 4d and Supplementary Figure S4b).

MSC-sheet therapy upregulated reparative factors more robustly than IM injection

To gain a further insight into the myocardial repair augmented by the MSC-sheet therapy, we performed quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction screening for factors relevant to MSC-mediated paracrine effects.1,5,6,7,9 As a result, we observed that myocardial expression of a range of factors was weakly (<1.5-fold) upregulated in the IM group at day 3 compared with the Sham group, which was more evidently amplified in the CS group, including TIMP-1, IGF-1, VCAM-1, SDF-1α, HIF-1α, and MMP-2 (Figure 4e). This amplified upregulation of reparative genes in the CS group agrees with the increased donor cell survival (Figure 2a) as well as promoted myocardial repair, i.e., increased capillary density and reduced pathological fibrosis (Figure 3a,b).

Comparisons of the effect of MSC-sheet therapy for AMI and ICM

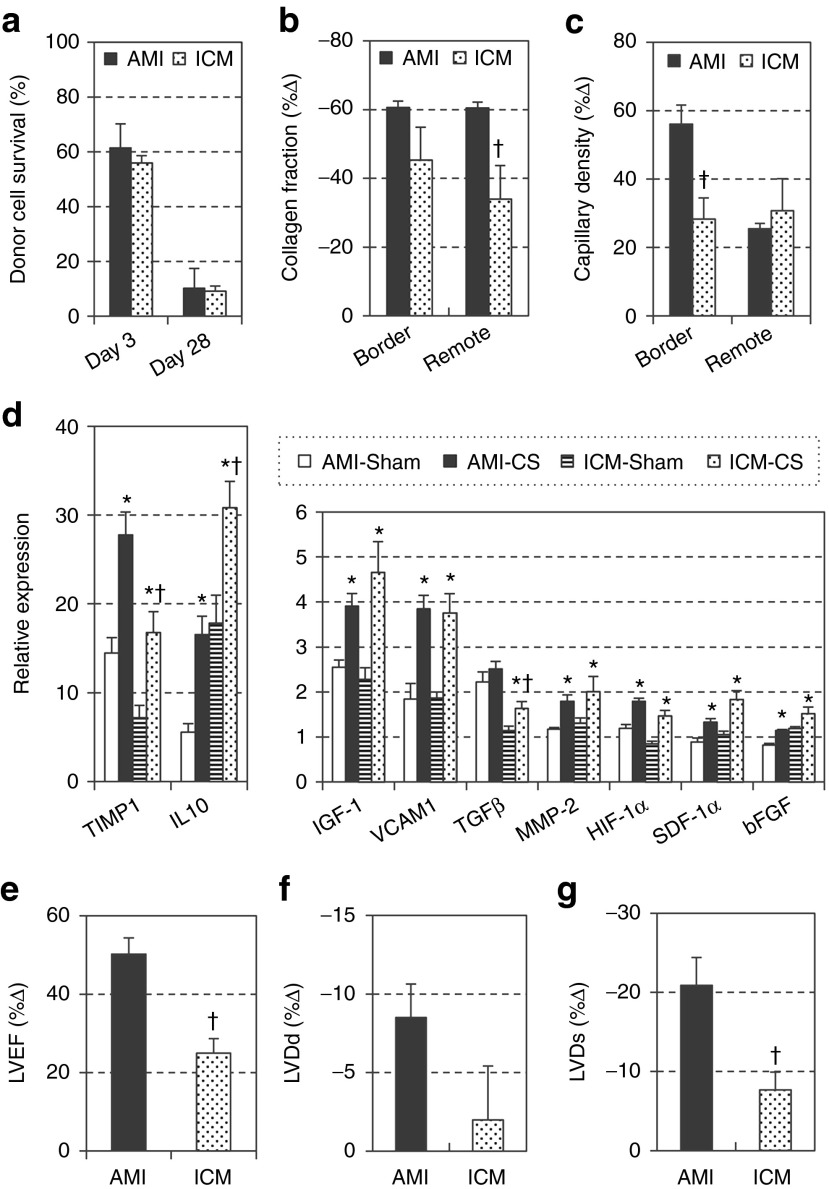

Although this and previous studies demonstrated that the MSC-sheet therapy is effective for the treatment of both AMI and ICM,9,11 it is likely that donor cell behavior as well as host myocardial responses after MSC-sheet therapy at cellular and molecular levels may be distinctive according to the host condition (i.e., AMI versus ICM). To date, there has been no report that investigated this aspect of MSC-based therapy in a comprehensive manner. By comparing with our published data of the MSC-sheet therapy for the treatment of AMI,9 in which the materials, protocols, and procedures used were all the same, this present study using an ICM model can provide new insights in this respect. The data from the two studies were standardized to each corresponding sham-group data (AMI-Sham and ICM-Sham) in order to allow comparisons, where needed. As a result, it was observed that donor cell survival after epicardial MSC-sheet placement was almost identical between the AMI and ICM models at both days 3 and 28 (Figure 5a). Donor cell localization was also the same, on the epicardial surface with minimum migration into the myocardium. These similarities corresponded with the analogous profile and degree of myocardial upregulation of paracrine factors relevant to myocardial repair and/or regeneration, including IGF-1, VCAM-1, MMP-2, HIF-1α, and SDF-1 (Figure 5d). Although expression of TIMP-1, IL-10, and TGF-β appeared to be different between the models, this could be due to different baseline (Sham-control in AMI versus Sham-control in ICM) values. Differentiation of donor MSCs was also comparable; endothelial differentiation (or fusion) was detectable similarly in both models, while no cardiomyogenic or mesenchymal differentiation was observed. On the other hand, responses of the host myocardium to these “similar” stimuli were different; reduction of collagen deposition and increase in capillary density in the ICM model were less substantial than in the AMI model (Figure 5b,c). Corresponding to this, improvement of heart function and reduction of cardiac dilatation were less extensive in ICM (Figure 5e–g). Collectively, it was demonstrated that the MSC-sheet therapy is able to provide similar survival, localization, differentiation, and secretion of donor MSCs in AMI and ICM, while the AMI-hearts are more sensitive and/or responsive to the stimuli from grafted MSCs.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of the effect of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-sheet therapy on ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) versus acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Effects of the MSC-sheet therapy in the ICM-heart were compared with the results in the AMI-hearts previously reported by us (ref. 9), including donor cell survival measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for sry (a). To enable comparisons, data of collagen volume fraction in the border area at day 28 post-treatment assessed by picrosirius red staining (b), capillary density in the border area at day 28 evaluated by Isolectin B4 staining (c), LVEF, LVDd, LVDs at day 28 measured by echocardiography (e–g), were standardized to each corresponding Sham group data, and shown as %▵ (= (values–Sham group value) ÷ Sham group value × 100). Myocardial expression of paracrine factors assessed by quantitative RT-PCR at day 3 is presented with normalization to the value of the normal intact hearts (d). †P < 0.05 versus AMI model, *P < 0.05 versus corresponding Sham. RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the MSC-sheet therapy (epicardial placement of scaffold-free MSC-sheets) provided augmented improvement of cardiac structure and function through markedly increased donor cell survival and amplified myocardial repair, compared to the current standard method, IM injection of MSC suspensions, in a post-MI ICM model in rat. In addition, MSC-sheet therapy offered safety advantages, including obviated formation of IM cell-clusters, which could cause electrical and mechanical disruption.6,7,16 The MSC-sheet therapy is also free from the risk of coronary embolism, which is a critical complication of intracoronary injection, particularly when this relatively larger-sized cell type is injected into diseased, narrowed coronary arteries with jeopardized collaterals.3,6,7 These proof-of-concept data for safety and efficacy encourage us to further develop the MSC-sheet therapy toward clinical application for treating ICM.

For clinical application of the MSC-sheet therapy, it will be a reasonable strategy to add it to elective coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). CABG is an established therapy for ICM patients who have the ischemic and viable myocardium; however the overall efficacy is not satisfactory.17 Of note, meta-analysis of clinical trials has shown that an addition of cell-therapy (even with the less-effective, current cell-delivery methods) increases therapeutic effects of CABG.18 In addition, in conjunction with CABG, the MSC-sheet therapy can save the shared costs for pre-/postevaluations and care, and for open chest surgery. The MSC-sheet therapy can be readily integrated into ordinary CABG; immediately after completion of bypass grafting, surgeons can place MSC-sheets on the surface of target myocardial areas (no suture needed), and then close the chest as usual. There are >7,000 ICM patients undergoing CABG every year in the United Kingdom,19 who could benefit from the MSC-sheet therapy. In future, this treatment may be conducted as a sole therapy by using a less-invasive endoscopic approach or small-incision surgery, which will further expand the application of this therapy.20

This study in an ICM model, in conjunction with our own previous report in an AMI model using the same materials, protocols, and procedures,9 provides important information regarding the timing of cell therapy for the treatment of MI at either acute or chronic phase. To our knowledge, there has been no direct comparison study that has systemically described the differences of donor cell behavior or difference in responsiveness of host myocardium due to different host conditions (ICM versus AMI) at cellular and molecular levels. Comparisons between this and previous9 reports, both from our laboratory, revealed that the MSC-sheet therapy was able to achieve similar retention, survival, localization, differentiation, and secretion of donor MSCs in AMI and ICM, while the AMI-hearts are more sensitive and/or responsive to the similar paracrine stimuli from grafted MSCs. We speculated that treatment in the acute phase has a disadvantage of reduced donor cell survival (and function) due to intense acute myocardial inflammation due to AMI. However, dynamics of epicardially placed cells did not appear to be affected by acute inflammation in AMI, compared to ICM; this may be because of diverse localization of donor cells (within the myocardium after injection versus on the epicardial heart surface after epicardial placement). On the other hand, the established mature infarct scar and surrounding myocardium suffering chronic stress in ICM was likely to be more difficult for the MSC-sheet therapy to repair, consistent to previous observations.21,22 These data will provide an important clue to optimize the timing to treat AMI patients by MSC-sheet therapy.

This preclinical study demonstrated that the MSC-sheet therapy provided substantial therapeutic effects for ICM, but there may be room to further improve the effect of this approach. Although the MSC-sheet therapy achieved a satisfactory donor cell retention and survival by day 3, there was significant amount of donor cell death between days 3 and 28. Our results suggested that vascular formation to feed the MSC-sheets might be insufficient. Although there were detectable neovascularization in the portion of cell-sheets adjacent to the heart with formation of connecting vessels between the sheets and the host myocardium, these events did not occur in the middle or outer layers of the MSC-sheets. It was presumed that this resulted in insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrition to the MSC-sheet, leading to progressive death of donor cells, which were replaced by fibrotic tissue. Thus, it will be useful to improve perfusion of the MSC-sheets for the purpose of further increasing donor cell survival and further enhancing the therapeutic effects. Sasagawa et al.23 have shown that prevascularization by adding endothelial cell-layers improves survival of multilayered myoblast-sheets which were generated by the temperature-responsive culture dishes. Kawamura et al.10 have reported that wrapping of the cell-sheets (generated with the same technology) with the omentum flap increases survival of induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes. Further study is warranted to develop clinically applicable solutions to this goal.

As the mechanism behind the effects of MSC-sheet therapy, we observed myocardial upregulation of various key factors, which are reported to play a role in the MSC-mediated paracrine effects. The paracrine effects mediated by MSCs are known to be extremely wide ranging, including neovascular formation, fibrosis reduction, anti-inflammation, myocardial regeneration through endogenous stem/progenitor cells, cardiomyocyte protection, etc.5,24,25 Therefore, it will be more reasonable to consider that a group of molecules collectively contribute to the paracrine effects in a synergistic or additive manner, rather than thinking that one single molecule or two induces all these benefits. In addition, it is an important issue whether these upregulated genes after MSC-sheet therapy were either from donor cells and/or host cells (in response to the stimuli from MSCs). Considering gene expression or protein secretion of cultured MSCs,5,26,27 most of genes we detected were likely to be from donor MSCs, but this does not exclude the possible contribution from host cardiac cells.

In general, macrophages are functionally polarized into classically activated M1 (proinflammatory) or alternatively activated M2 (anti-inflammation and tissue healing) phenotypes according to the environmental condition. We found that the MSC-sheet therapy increased the number of CD163+ M2-like macrophages, which could play a role in the paracrine effects. Recent research has shown that the adult mouse heart contains heart-resident macrophages that have an alternatively activated M2-like phenotype.28 These cells have diverse subpopulations; some subsets are originated from yolk sack, while others are recruited from the bone marrow.29 However, detailed characterization of these subsets remains incomplete. It will be interesting to identify the origin and characteristics of accumulated CD163+ cells after the MSC-sheet therapy; however, it was not possible here because our study was not designed to investigate this point. Further study using an appropriate model, e.g., bone marrow chimera animals or genetically labeled animals, is warrantied.

To conclude, epicardial placement of scaffold-free MSC-sheets that were produced with temperature-responsive dishes, provided augmented recovery of function and structure of the heart suffering ICM, through increased donor cell survival and promoted myocardial repair, compared to the current cell-delivery method. These in vivo proof-of-concept data encourage us to progress further development of this approach toward clinical application.

Materials and Methods

All studies were performed with the approval of the institutional ethics committee and the Home Office, UK. The investigation conforms to the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (US National Institutes of Health Publication, 1996). All in vivo and in vitro assessments were carried out in a blinded manner.

Isolation, culture, and characterization of rat bone marrow–derived MSCs. MSCs were isolated from the bone marrow of the tibias and femurs of male Lewis rats (100–150 g; Charles River UK, Margate, UK) as described previously.9 MSCs at passage 3 or 4 were used for studies. For histological tracking of donor cells, MSCs were labeled with CM-DiI (Molecular Probes; Paisley, UK) as we have previously described.30

For cell surface marker characterization using flow-cytometry, 1 × 106 MSCs at passage 3–5 were stained with 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-CD34 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), CD45 (Chemicon, Hampshire, UK), CD90 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or Alexa 647-conjugated anti-CD29 (Biolegend, London, UK) antibodies. Corresponding isotype-matched control antibodies were used for negative controls. Samples were analyzed using the Dako Cyan flow-cytometer (Dako Cytomation, Stockport, UK).

Cultured MSCs at passage 3–5 were transferred to 24-well plates and subjected to adipogenic or osteogenic differentiation medium as previously described.9,31 Adipogenic differentiation medium was α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 100 μmol/l isobutyl methylxathine (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK), 60 μmol/l indomethacin (Fluka, Dorset, UK), 1 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.5 μmol/l hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich). Osteogenic differentiation medium was α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 0.1 μmol/l dexamethasone, 10 mmol/l β-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mmol/l ascorbic acid (all from Sigma-Aldrich). Medium was changed every 2–3 days. After 3 weeks incubation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with Oil red O (Fluka) for detecting adipocytes containing lipid vacuoles or with Alizarin red (Fluka) to detect osteocytes containing calcium deposits.9,31 All results of these characterisations (Supplementary Figure S5) consistently demonstrated that the collected cells were MSCs.

Generation of MSC-suspensions and MSC-sheets. To generate an MSC-sheet, 4 × 106 MSCs (passage 3–4) were seeded onto a 35 mm temperature-responsive dish (CellSeed, Tokyo, Japan). Fourteen hours after incubation at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the culture dish was placed at 20–22 °C, and the MSC-sheet detached from the dish as a free cellular-membrane.8,9,10 We have confirmed that the cell suspension generated from a freshly produced MSC-sheet by trypsin digestion contained 4.02 ± 0.1 × 106 (n = 3), assuring that there was no difference in the MSC number between cell-sheet and IM injection groups. For IM injection, 4 × 106 MSCs were collected using trypsinization and suspended in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline.9,14,16

Animal surgery. MI was induced in female Lewis rats (150–200 g; Charles River UK) by ligating the left coronary artery under mechanical ventilation as described previously.9,14,16 At 4 weeks, rats were subjected to echocardiography, and those showing inappropriate LVEF (>45% or <25%) were excluded from the study.9,14 Included animals were randomly allocated into three groups and assigned to undergo transplantation of 4 × 106 MSCs from syngeneic male rats under rethoracotomy by epicardial placement of a MSC-sheet (CS group) or by either IM injection (IM group). For the CS group, an MSC-sheet was placed on the heart surface to cover the infarct and surrounding border areas. After placement, MSC-sheets were found to stably adhere to the heart within a half hour. For the IM group, MSCs suspended in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline, and 100 μl of MSC suspension was injected through a 29G needle at each of two sites (one into the anterior LV wall and the other into the posterior LV wall, both aiming cell delivery to the border and infarct areas). The needle was inserted at an angle into the viable border area and advanced up to the endocardial part of the myocardium. Injection into the LV cavity was avoided by confirming no blood aspiration. While pulling out the needle, the MSC suspension was gently and slowly introduced at several depths to deliver cells from endocardial to epicaridial layers over 1–2 minutes. We avoided high pressure to minimize damage to the host myocardium and donor cells. After all the suspension was delivered, the needle was held for another 1 minute before slow and careful removal in order to minimize leakage of injected cell suspension from the injection site. There was no case that showed visual leakage in this study. We confirmed that this IM injection protocol achieves retention of a sizeable amount of donor MSCs (Supplementary Figure S6). Sham treatment (open chest surgery only) was performed as control (Sham group). After treatment, samples were collected at selected time points for assessments.

Cardiac performance measurement. Transthoracic echocardiographic determinations were assessed pretreatment (4 weeks after MI) and at 28 days post-treatment by using Vevo-770 ultrasound machine (VisualSonics, Amsterdam, Netherlands) under 1.5% isoflurane inhalation. LVEF was calculated from the data obtained with two-dimensional tracing. LV end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions (LVDd and LVDs), LV wall thickness, and heart rate were measured with M-mode. Transmitral peak E/A flow ratio was determined by spectral Doppler traces. All data were collected from at least three to five different measurements in a blinded manner.

Hemodynamic parameters were measured by using cardiac catheterization (SPR-320; Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) as previously described.9,30 Briefly, under general anesthesia using isoflurane and mechanical ventilation, the catheter was inserted into the LV cavity through the right common carotid artery. Intra-LV and intra-aortic pressure signals were measured with a transducer and conditioner (MPVS-300; Millar Instruments) and digitally recorded with a data acquisition system (PowerLab 8/30; ADInstruments, Oxford, UK). All data were collected from at least five different measurements in a blinded manner.

Quantitative assessment of donor cell survival. To quantitatively evaluate the presence of male donor cells in the female host heart, the Y chromosome–specific sry gene was assessed by real-time PCR (Prism 7900HT; Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK).9,30 At 3 and 28 days after treatment, the ventricular walls were collected, from which genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood&Tissue kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) for the sry detection. The signal in each sample was normalized to the amount of DNA by measuring the autosomal single-copy gene osteopontin as an internal standard.9,30 For generating a standard curve, the ventricular walls from female rats at 56 days after left coronary artery ligation were mixed with known numbers (1 × 107, 1 × 106, 1 × 105, 1 × 104) of male MSCs, genomic DNA prepared, and sry content analyzed (n = 3).

Analysis of myocardial gene expression. Total RNA was extracted from the ventricular walls by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and assessed for myocardial gene expression likely relevant to the MSC-mediated paracrine effect by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Prism 7900HT; Applied Biosystems) as previously described.9,30 All TaqMan primers and probes except thymocine-β4 (Sigma-Aldrich) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Expression was normalized to Ubiquitin C, and relative expression to that in the Sham group, which was assigned to be 1.0, is presented in the figures.

Histological analysis. The hearts were harvested, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and frozen in the optimal cutting temperature compound in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections were cut and incubated with polyclonal anti-cTnT antibody (1:200 dilution; HyTest, Turku, Finland), biotin-conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia lectin I-isolectin B4 (1:100; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK), monoclonal anti-PECAM1 antibody (1:50; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK), monoclonal anti-CD86 antibody (1:100; BD Pharmingen, Oxford, UK) or monoclonal anti-CD163 antigen antibody (1:200; AbD Serotec), followed by visualization using fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Sections were then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (BZ8000; Keyence, Milton Keynes, UK) with or without nuclear counterstaining using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Ten different fields from each of the border and remote areas per heart were randomly selected and assessed.

Another set of sections were stained with 0.1% picrosirius red (Sigma-Aldrich) to assess infarct size (% of scar length to total left ventricular circumference as previously described)9,32 and wall thickness,33 and to quantify collagen fraction using NIH image-analysis software.9,30 In addition, for detecting adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation, staining with Oil red O (Sigma-Aldrich) and Alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed as previously described.9 Samples were observed and analyzed by light microscopy (BZ8000; Keyence).

Statistical analysis. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparison of two groups was performed using the student's unpaired t-test. Other data were statistically analyzed with one-way or two-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference test to compare groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. In vitro characterization of rat bone marrow-derived MSCs. Figure S2. Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in vivo. Figure S3. Histological analyses of the infarcted area after treatment. Figure S4. Supplementary data to Figure 4a,b (Enhanced myocardial repair by MSC-sheet therapy). Figure S5. Supplementary data to Figure 4c,d (Macrophage accumulation by MSC-sheet therapy). Figure S6. Initial donor cell retention after IM injection. Table S1. Changes in cardiac function measured by echocardiography. Table S2. Cardiac catheterisation analysis at day 28 post-treatment.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the British Heart Foundation (PG/12/10/29389) and Heart Research UK (RG2618/12/13), and supported by the National Institute for Health Research-funded Barts Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

In vitro characterization of rat bone marrow-derived MSCs.

Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in vivo.

Histological analyses of the infarcted area after treatment.

Supplementary data to Figure 4a,b (Enhanced myocardial repair by MSC-sheet therapy).

Supplementary data to Figure 4c,d (Macrophage accumulation by MSC-sheet therapy).

Initial donor cell retention after IM injection.

Changes in cardiac function measured by echocardiography.

Cardiac catheterisation analysis at day 28 post-treatment.

References

- Kode JA, Mukherjee S, Joglekar MV, Hardikar AA. Mesenchymal stem cells: immunobiology and role in immunomodulation and tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:377–391. doi: 10.1080/14653240903080367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus HM, Haynesworth SE, Gerson SL, Rosenthal NS, Caplan AI. Ex vivo expansion and subsequent infusion of human bone marrow-derived stromal progenitor cells (mesenchymal progenitor cells): implications for therapeutic use. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16:557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113:810–834. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malliaras K.Li TS.Luthringer D.Terrovitis J.Cheng K.Chakravarty T.et al. (2012Safety and efficacy of allogeneic cell therapy in infarcted rats transplanted with mismatched cardiosphere-derived cells Circulation 125100–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NG, Suzuki K. Cell delivery routes for stem cell therapy to the heart: current and future approaches. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:713–726. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima S, Sawa Y, Suzuki K. Choice of cell-delivery route for successful cell transplantation therapy for the heart. Future Cardiol. 2013;9:215–227. doi: 10.2217/fca.12.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siltanen A, Kitabayashi K, Lakkisto P, Mäkelä J, Pätilä T, Ono M.et al. (2011hHGF overexpression in myoblast sheets enhances their angiogenic potential in rat chronic heart failure PLoS One 6e19161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita T, Shintani Y, Ikebe C, Kaneko M, Campbell NG, Coppen SR.et al. (2013The use of scaffold-free cell sheet technique to refine mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapy for heart failure Mol Ther 21860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Fukushima S, Saito A, Miki K, Ito E.et al. (2013Enhanced survival of transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by the combination of cell sheets with the pedicled omental flap technique in a porcine heart Circulation 12811 suppl. 1S87–S94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi H, Planat-Benard V, Bel A, Puymirat E, Geha R, Pidial L.et al. (2011Epicardial adipose stem cell sheets results in greater post-infarction survival than intramyocardial injections Cardiovasc Res 91483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajarsa JJ, Kloner RA. Left ventricular remodeling in the post-infarction heart: a review of cellular, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic modalities. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach M, Bostani T, Roell W, Xia Y, Dewald O, Nygren JM.et al. (2007Potential risks of bone marrow cell transplantation into infarcted hearts Blood 1101362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Shintani Y, Narita T, Ikebe C, Tano N, Yamahara K.et al. (2013Extracellular high mobility group box 1 plays a role in the effect of bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation for heart failure PLoS One 8e76908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Mordechai T, Holbova R, Landa-Rouben N, Harel-Adar T, Feinberg MS, Abd Elrahman I.et al. (2013Macrophage subpopulations are essential for infarct repair with and without stem cell therapy J Am Coll Cardiol 621890–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima S, Varela-Carver A, Coppen SR, Yamahara K, Felkin LE, Lee J.et al. (2007Direct intramyocardial but not intracoronary injection of bone marrow cells induces ventricular arrhythmias in a rat chronic ischemic heart failure model Circulation 1152254–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, Jain A, Sopko G, Marchenko A.et al.; STICH Investigators 2011Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction N Engl J Med 3641607–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donndorf P, Kundt G, Kaminski A, Yerebakan C, Liebold A, Steinhoff G.et al. (2011Intramyocardial bone marrow stem cell transplantation during coronary artery bypass surgery: a meta-analysis J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 142911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman R, Systems DC.2008The Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland Sixth National Adult Cardiac Surgical Database Report . < http://www.scts.org/_userfiles/resources/SixthNACSDreport2008withcovers.pdf >.

- Kimura T, Miyoshi S, Okamoto K, Fukumoto K, Tanimoto K, Soejima K.et al. (2012The effectiveness of rigid pericardial endoscopy for minimally invasive minor surgeries: cell transplantation, epicardial pacemaker lead implantation, and epicardial ablation J Cardiothorac Surg 7117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Bertaso AG, Psaltis PJ, Frost L, Carbone A, Paton S.et al. (2013Impact of timing and dose of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in a preclinical model of acute myocardial infarction J Card Fail 19342–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Huang ML, Liu KY, Jia ZB, Sun L, Jiang SL.et al. (2012Inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase by cell-based timp-3 gene transfer effectively treats acute and chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy Cell Transplant 211039–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa T, Shimizu T, Sekiya S, Haraguchi Y, Yamato M, Sawa Y.et al. (2010Design of prevascularized three-dimensional cell-dense tissues using a cell sheet stacking manipulation technology Biomaterials 311646–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Shou M, Lee CW, Barr S.et al. (2004Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms Circulation 1091543–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupcova Skalnikova H. Proteomic techniques for characterisation of mesenchymal stem cell secretome. Biochimie. 2013;95:2196–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto AR, Paolicelli R, Salimova E, Gospocic J, Slonimsky E, Bilbao-Cortes D.et al. (2012An abundant tissue macrophage population in the adult murine heart with a distinct alternatively-activated macrophage profile PLoS One 7e36814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B.et al. (2014Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation Immunity 4091–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita T, Shintani Y, Ikebe C, Kaneko M, Harada N, Tshuma N.et al. (2013The use of cell-sheet technique eliminates arrhythmogenicity of skeletal myoblast-based therapy to the heart with enhanced therapeutic effects Int J Cardiol 168261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Nishida T, Ishii S, Iijima H.et al. (2008Topical transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells accelerates gastric ulcer healing in rats Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294G778–G786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagawa J, Zhang Y, Wong ML, Sievers RE, Kapasi NK, Wang Y.et al. (2007Myocardial infarct size measurement in the mouse chronic infarction model: comparison of area- and length-based approaches J Appl Physiol (1985) 1022104–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane AA, Chuang JS, Shah A, Hu DP, Dalton ND, Gu Y.et al. (2011Increased infarct wall thickness by a bio-inert material is insufficient to prevent negative left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction PLoS One 6e21571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In vitro characterization of rat bone marrow-derived MSCs.

Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in vivo.

Histological analyses of the infarcted area after treatment.

Supplementary data to Figure 4a,b (Enhanced myocardial repair by MSC-sheet therapy).

Supplementary data to Figure 4c,d (Macrophage accumulation by MSC-sheet therapy).

Initial donor cell retention after IM injection.

Changes in cardiac function measured by echocardiography.

Cardiac catheterisation analysis at day 28 post-treatment.