Abstract

Objective. To assess the long-term sustainability of continuing professional development (CPD) training in pharmacy practice and learning behaviors.

Methods. This was a 3-year posttrial survey of pharmacists who had participated in an unblinded randomized controlled trial of CPD. The online survey assessed participants’ perceptions of pharmacy practice, learning behaviors, and sustainability of CPD. Differences between groups on the posttrial survey responses and changes from the trial’s follow-up survey to the posttrial survey responses within the intervention group were compared.

Results. Of the 91 pharmacists who completed the original trial, 72 (79%) participated in the sustainability survey. Compared to control participants, a higher percentage of intervention participants reported in the sustainability survey that they had utilized the CPD concept (45.7% vs 8.1%) and identified personal learning objectives (68.6% vs 43.2%) during the previous year. Compared to their follow-up survey responses, lower percentages of intervention participants reported identifying personal learning objectives (94.3% vs 68.6%), documenting their learning plan (82.9% vs 22.9%) and participating in learning by doing (42.9% vs 14.3%) in the sustainability survey. In the intervention group, many of the improvements to pharmacy practice items were sustained over the 3-year period but were not significantly different from the control group.

Conclusion. Sustainability of a CPD intervention over a 3-year varied. While CPD-trained pharmacists reported utilizing CPD concepts at a higher rate than control pharmacists, their CPD learning behaviors diminished over time.

Keywords: Continuing pharmacy education, continuing professional development, education outcomes, learning behaviors, pharmacy practice, sustainability

INTRODUCTION

Traditional continuing pharmacy education (CPE) is typically based on completing predefined learning activities to earn credit hours towards pharmacist relicensure without the ability to personalize learning objectives. Continuing professional development, in contrast, is a systematic learning process that is self-directed using a 4-stage cycle (reflect, plan, act, and evaluate).1,2 Reflecting on one’s personal knowledge, skills, and competence aids in the creation of a personal development plan designed to address personal learning needs. Activities are then chosen to meet identified, personalized learning objectives, which are evaluated upon completion to determine if they have been achieved.2

While the effect of CPD on learning and practice has been investigated among physicians, little evidence has been reported of its efficacy among pharmacists. In 2008, Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) conducted a pre-post, randomized controlled trial of 100 pharmacists to assess the effect of CPD compared to traditional continuing pharmacy education (CPE) on perceptions of factors related to pharmacy practice and learning behaviors.3,4 While the CPD arm had significant improvements in perceptions of both pharmacy practice and learning behaviors relative to the CPE arm in the trial, it is unknown if these improvements are sustainable over time. Sustainability of these changes would imply that the benefits of finite CPD training would perpetuate without the need for additional interventions or motivations. The objective of this study was to assess the long-term sustainability of CPD training in changes to pharmacy practice and learning behaviors.

METHODS

A survey of pharmacists was conducted at KPCO, a not-for-profit integrated health care delivery system that, at the time of the survey, employed over 300 full-time and part-time pharmacists and provided services to more than 530 000 members. Pharmacists who participated in the CPD trial and were still KPCO employees were invited to participate in an online sustainability survey in May 2012, approximately 3 years after the CPD trial.3,4 The survey queried pharmacists on perceptions of pharmacy practice and learning behaviors and the sustainability of CPD. Approval to conduct this survey was obtained from the KPCO Institutional Review Board. Re-consent was not required by the review board as participation in the sustainability survey was voluntary and only open to pharmacists who were consented for the CPD trial.

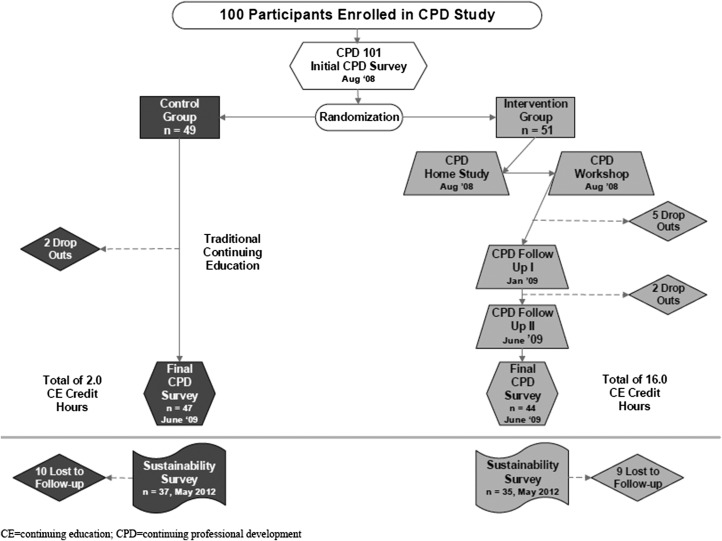

All full-time and part-time licensed pharmacists at KPCO were eligible to participate in the original trial and recruited via e-mail and at departmental meetings. Participants were provided a 2-hour “CPD 101” that detailed the history and principles of CPD and then randomized into the intervention (CPD group) or control arm. Intervention participants were provided instruction on the CPD model and how to utilize the CPD concept for their education needs. They completed 3 hours of home study about the CPD concept and a 7-hour, in-person workshop with hands-on training and participation in the CPD process. The intervention group kept track of their educational progress in a personal online CPD portfolio. In addition, their progress toward completing the learning objectives was checked at two 2-hour follow-up workshops at 5 and 10 months after the initial workshop. Nonintervention participants (control group) were instructed to maintain the traditional CPE process. In Colorado, the minimum number of credit hours needed for relicensure is 24 every 2 years (Figure 1). At the time of this survey, no monitoring of CPE for the participants occurred beyond that of the activities required by the Colorado State Board of Pharmacy.

Figure 1.

Study Timeline and Pharmacist Dispositions

Items on the sustainability survey’s questionnaire assessed participants’ perceptions of pharmacy practice and learning.3 Briefly, the questionnaire was developed by a CPD task force from previously administered educational questionnaires,5 and items were categorized as pharmacy practice, learning behaviors, and professional development sections. The CPD trial included a baseline and follow-up survey with a questionnaire, and changes in item responses were compared between the study arms. For the sustainability survey, items related to the sustainability of CPD were added to the trial questionnaire. These included items such as “In the past year, have you utilized the CPD concept?” and “In the past year, have you utilized a CPD portfolio?”

The primary outcomes were between-group comparisons of responses to sustainability survey items concerning pharmacy practice, learning behavior, and CPD sustainability. The secondary outcomes were within-group comparisons of the intervention group’s responses to items from the trial follow-up and the sustainability surveys involving intraparticipant changes to the pharmacy practice and learning behavior.

It was estimated that 85 participants would be included in the sustainability survey. With 85 participants, a phi effect size of 0.20 in the intervention group could be detected with 80% power at an alpha of 0.05. For example, a significant difference would be detected if 25 (61%) intervention and 17 (39%) control participants or 12 (29%) intervention and 5 (11%) control participants answered in the affirmative.

Data were collected from participants via online administration of the sustainability questionnaire. To increase study power, responses were dichotomized to reflect affirmative and nonaffirmative responses (eg, strongly agree/agree vs all other responses including unsure/neutral, and frequently/always vs all other responses including unsure/neutral). Response results and respondent characteristics are reported as percentages. Differences between groups’ percentages were compared using the chi-square tests of association or the Fisher exact test depending on the distribution of the cell counts (actual vs expected results). Intraparticipant changes in responses were compared using McNemar tests. To assess whether participant education and experience had an impact on response results, multivariable logistic regression modeling was performed on results with significant between-group differences in the bivariate analyses. Models included the response result and group as the dependent and independent variables, respectively, with adjustment for education (PharmD vs BSPharm) and years of pharmacist experience (0-1, 2-5, 6-10, >10 years). All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC) with the alpha set at 0.05.

RESULTS

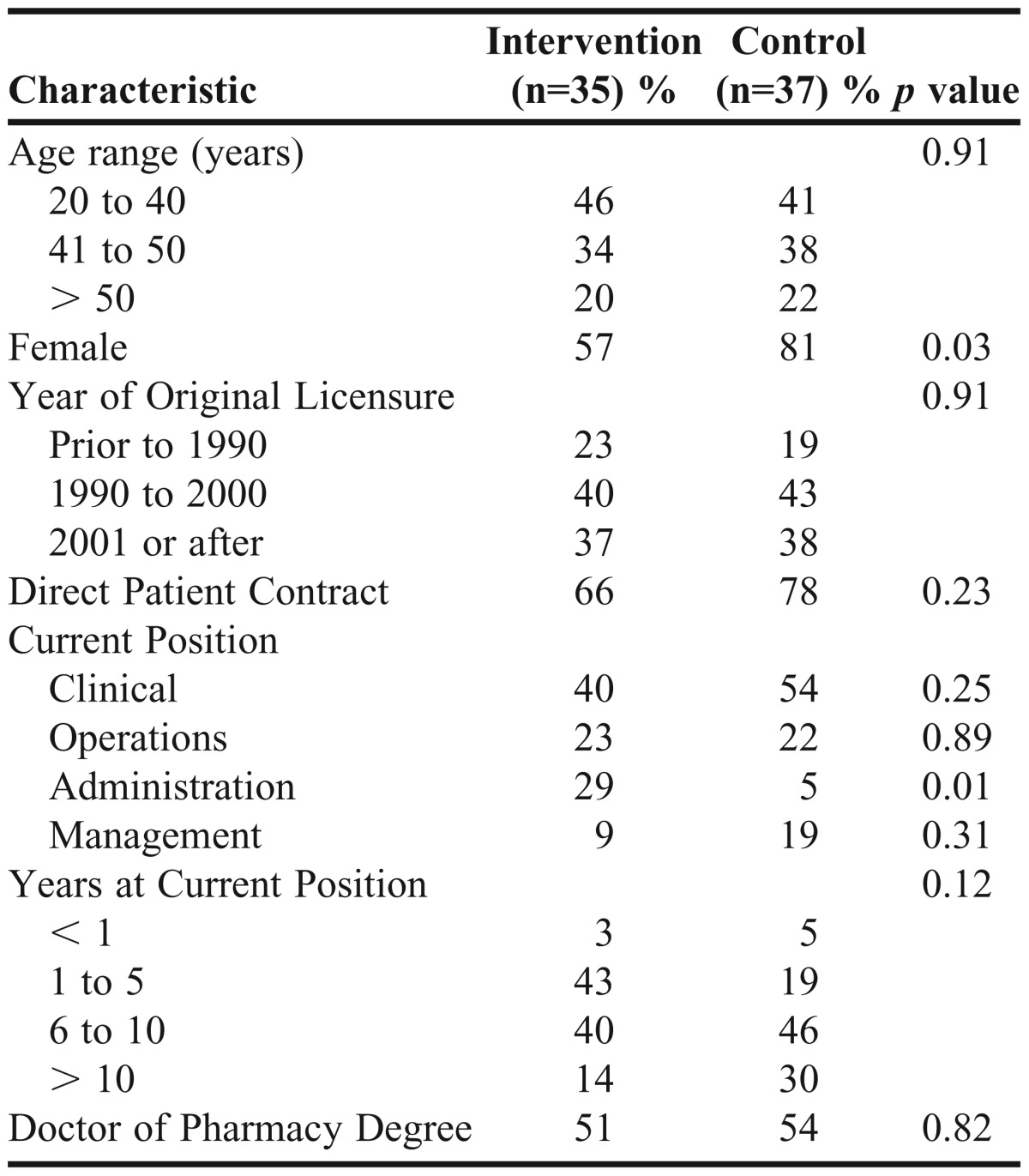

Of the original 100 pharmacists enrolled, 91 pharmacists completed the CPD randomized controlled trial, and 87 of these pharmacists still were employed by KPCO at the time the sustainability survey was administered. Seventy-two pharmacists participated in the sustainability survey, constituting 80% and 78% of the intervention and control pharmacists, respectively, who completed the CPD trial. The intervention (n=35) and control (n=37) groups were similar except that there were higher proportions of men and administrative staff in the intervention group (both p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Study Group at time of Sustainability Survey

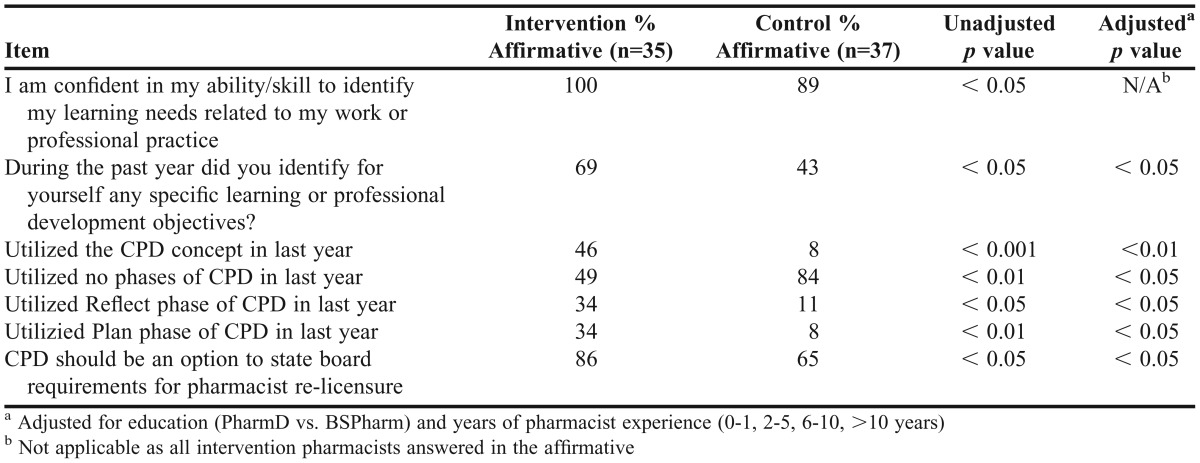

When comparing control and intervention responses from the sustainability survey, more intervention participants than control participants reported they were confident in their perception of their ability to identify their learning needs related to their work or professional practice (100% vs 89.2%, p<0.05; p value with adjustment not applicable because all intervention pharmacists responded in the affirmative) (Table 2). Similarly, a higher percentage of intervention than control participants reported they had identified personal learning objectives in the previous year (68.6% vs 43.2%, p<0.05, p<0.05 with adjustment). A higher percentage of intervention compared to control participants reported utilizing the CPD concept in the last year (45.7% vs 8.1%, p<0.001, p<0.01 with adjustment). While the majority of intervention (85.7%) and control (64.9%) participants agreed that CPD should be an option for state board requirements for pharmacist relicensure, more intervention than control participants responded in the affirmative (p<0.05, p<0.05 with adjustment).

Table 2.

Significant Affirmative Responses from the Sustainability Survey by Study Group: Learning Behaviors

Although there were differences between groups in the proportion of affirmative responses to perceptions of learning behaviors, no significant differences were identified between groups on the perceptions of pharmacy practice items in the sustainability survey. For example, similar percentages in the intervention and control groups reported perceptions of gaining meaningful learning from education activities (42.9% vs 40.5%, respectively), applying learning from educational programs to work (22.9% vs 18.9%, respectively), reinforcing learning from educational programs through practice (20.0% vs 27.0%, respectively), and making a conscious commitment to do something as a result of education activities (17.1% vs 24.3%, respectively) (all p>0.05). In addition, perceptions of the 2 groups were similar regarding educational activities enhancing professional knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. And finally, no differences were identified between the groups in perceptions of their ability to answer patient questions (28.6% vs 24.3%), to increase depth of patient counseling (28.6% vs 16.2%), to change patient care (20.0% vs 18.9%), to provide better medication therapy management services (20.0% vs 18.9%), or to interact better with other health care professionals (11.4% vs 16.2%) as a result of education activities (all p>0.05).

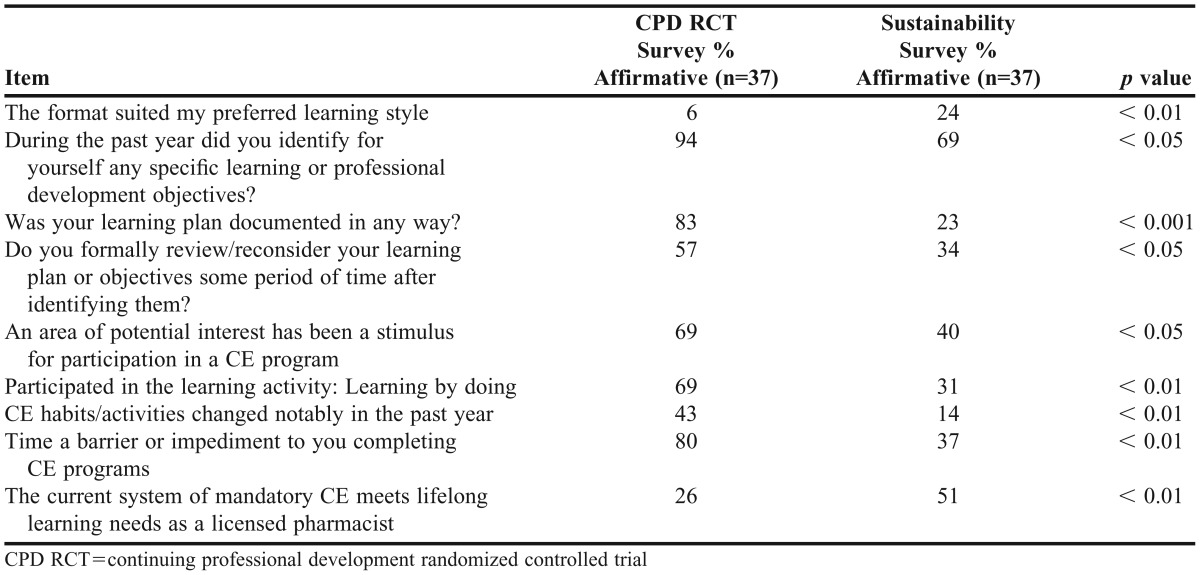

Regarding intraparticipant changes in responses from the CPD trial follow-up survey to sustainability survey (Table 3), fewer intervention participants reported in the latter that they had identified personal learning objectives (68.6% vs 94.3%, p<0.01). Additionally, fewer intervention participants reported in the sustainability survey documenting their learning plan (22.9% vs 82.9%, p<0.001) or reviewing/reconsidering their learning plan (34.3% vs 57.1%, p<0.05). Furthermore, fewer intervention participants reported in the sustainability survey selecting a program based on potential interest (40.0% vs 68.6%, p<0.05) and participating in learning by doing (31.4% vs 68.6%, p<0.01).

Table 3.

Significant Intraparticipant Survey Response Comparisons of the Intervention Group: Learning Behaviors

In the CPD trial follow-up survey, intervention participants reported perceiving that their continuing education habits/activities had changed notably in the previous year. However in the sustainability survey, fewer intervention participants reported a perception of a change in educational habits/activities within the previous year (14.3% vs 42.9%, p<0.01). In addition, the perception that time was a barrier to completing continuing education was reported by fewer intervention participants in the sustainability survey than in the trial follow-up survey (37.1% vs 80.0%, p<0.01). Twice as many intervention participants in the sustainability survey than in the trial follow-up survey reported that the current system of mandatory continuing education was meeting their lifelong learning needs (51.4% vs 25.7%, p<0.01).

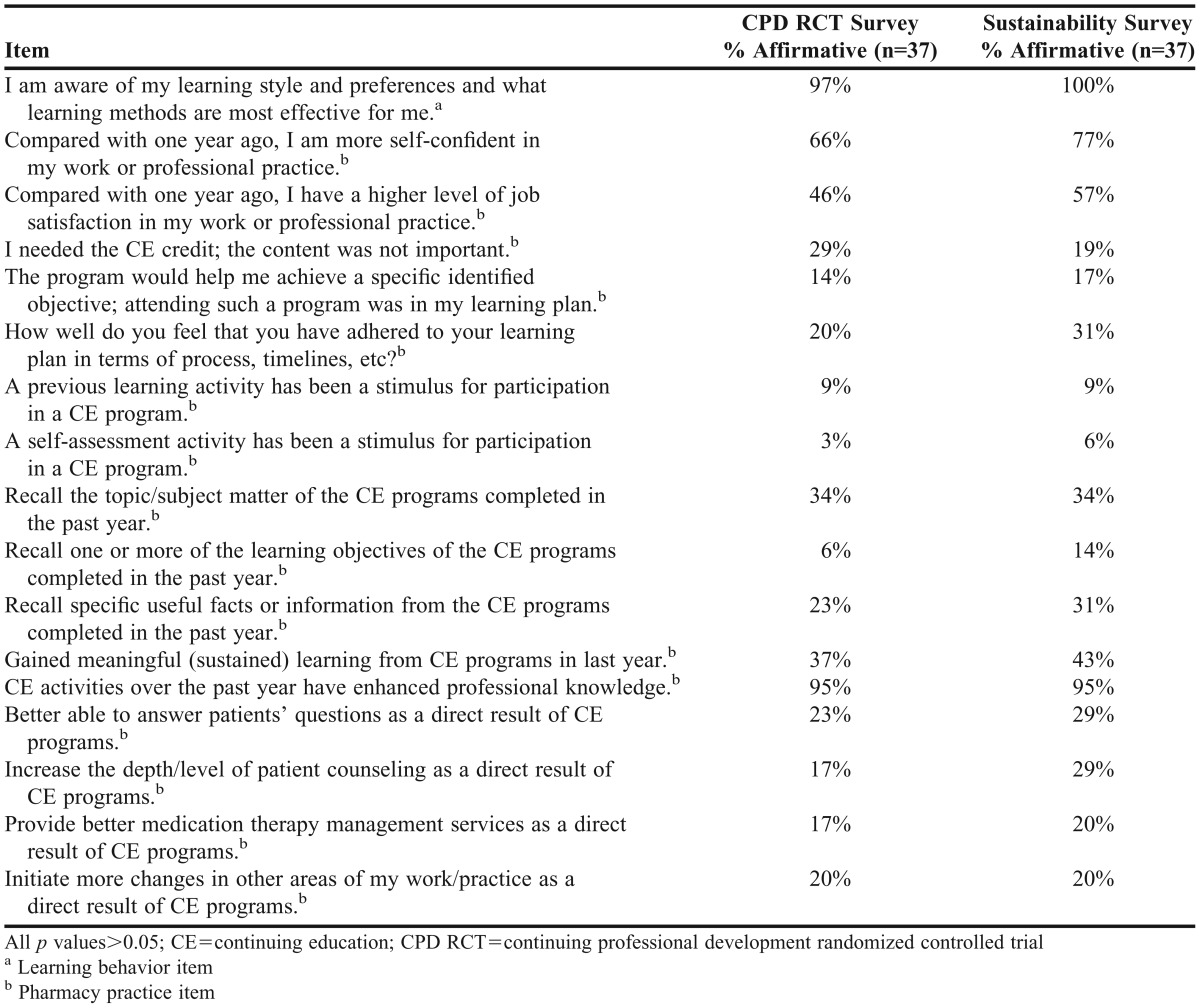

While there were no significant changes in the pharmacy practice items from the CPD trial survey to the sustainability survey for the intervention group, many of the responses either remained the same or slightly improved (Table 4), implying sustainability. Pharmacists in the intervention group reported to the same degree in both surveys that they perceived continuing education programs helped them better answer patients’ questions, increase the depth/level of patient counseling, provide better medication therapy management services, and initiate changes to their practice (all p>0.05).

Table 4.

Items Demonstrating Sustainability from the Intervention Group Intraparticipant Survey Response Comparisons

DISCUSSION

In this 3-year posttrial survey of pharmacists who had participated in a randomized controlled trial of a CPD intervention, we found that the long-term sustainability of changes to pharmacy practice and learning behaviors from CPD training varied. While CPD-trained pharmacists reported utilizing CPD concepts at a higher rate than control pharmacists in the sustainability survey, there was decay in their utilization over time. For example, pharmacists in the intervention group reported continuing to identify personal learning objectives in both surveys, but in the sustainability survey, fewer reported documenting and reconsidering their learning plans compared to responses from the CPD trial survey. Moreover, in the sustainability survey, fewer intervention pharmacists reported choosing their continuing education program based on interest and participating in learning by doing.

The intervention group demonstrated perceived sustainability on some pharmacy practice items, but these items were not statistically different from the control group. Our findings indicate that while an intensive CPD intervention, which included a 7-hour workshop, home study and 2 follow-up sessions, resulted in some sustained perceptions of learning behavior differences, the intervention group’s differences decayed and were similar to the control group’s over time.

To our knowledge, there are no published reports regarding the sustainability of acquired knowledge and skills for pharmacists. Information on sustainability of continuing medical education is also limited. For example, Schichtel and colleagues’ review of 21 randomized controlled trials examined the effectiveness of continuing medical education interventions for primary health care professionals to promote the early diagnosis of cancer.6 Interactive education, reminder systems, and audit/feedback demonstrated positive effects on early diagnosis of cancer compared to didactic teaching alone. However, the authors stated that the evidence for the durability and sustainability of these interventions was limited and warranted further research.6 In 2010, a Cochrane Review was completed to assess the effectiveness of interventions for increasing the frequency and quality of questions formulated by health care providers in practice and in the context of self-directed learning.7 Four studies were identified that examined interventions to improve question formulation in health care professionals; 3 of the 4 studies demonstrated improvement in the short-term to moderate-term term follow up.7 However, only Cheng examined sustainability of effects over time and reported that information-seeking skills had eroded at one year.8 The authors of the Cochrane Review concluded that the sustainability of effects from educational interventions for question formulation was unknown. As these studies indicate, the sustainability of acquired knowledge and skills is either unknown or decays over time. Our study identified that perceptions of learned skills gained from a CPD intervention eroded over time. Thus, one must ask why perceptions of learning behaviors decay over time.

In 2011, Donyai and colleagues published a comprehensive review of the literature on the uptake of and attitudes towards CPD among British pharmacists.9 In the 22 studies included, barriers to CPD were identified, including time and motivation to participate in CPD. In our study, we identified that time continues to be a barrier to using CPD; approximately twice as many participants reported in the CPD trial follow-up survey than in the sustainability survey 3 years later that time was a barrier. This suggests that the intervention pharmacists allotted less (or no) time to participate in CPD, resulting in a decay in learning from CPD.

Another explanation of decay seen with CPD over time may be that pharmacists need external motivation to routinely utilize the CPD concept of self-directed learning. While pharmacists were enrolled in our CPD trial, study investigators followed up with them periodically to provide them with the opportunity to reflect and reconsider their learning objectives. However, once the study ended, there was no extrinsic motivation to encourage the pharmacists to continue CPD. If other external motivations and/or protected time existed, pharmacists may be more likely to engage in CPD and choose educational activities that pertain directly to their work.

Potential sources of external motivation are licensing bodies, such as state boards of pharmacy, certification organizations such as the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS), or pharmacist employers. State boards of pharmacy could consider incorporating aspects of CPD into the relicensure process. This, in turn, may make the requirement for maintaining licensure more applicable to the pharmacists and their work. Australia, Great Britain, and New Zealand have incorporated CPD into the relicensure requirements for their pharmacists. In the United States, however, only pharmacists licensed in North Carolina have the option to use a CPD portfolio for relicensure.10 With traditional CPE, there is no requirement for participants to assess or address their learning needs. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions” stated that, among various problems, health professionals and their employers tend to focus on meeting regulatory requirements rather than identifying personal knowledge gaps and finding programs to address them.11 If state boards of pharmacy provided external motivation to fulfill personal learning objectives by granting credit toward licensure renewal, pharmacists might choose alternatives to typical lecture-style education activities, such as learning by doing, on a more routine basis and complete in the time already allotted to complete relicensure activities.

Another source of external motivation for CPD could be from the BPS, an independent nongovernmental certification body that has provided recognition of persons involved in the advanced practice of pharmacy specialties since 1976.12 Once a pharmacist has been board certified via examination through BPS, recertification is required every 7 years to evaluate their current knowledge and skills. Recertification can be completed via BPS-approved CPE activities or through a BPS-administered recertification examination. However a lack of structured self-assessment occurs during this recertification period. Board-certified pharmacists may be taking any available BPS-approved CPE to fulfill recertification requirements without considering if the education will apply to their practice, improve outcomes of the patients and populations they serve, or fill an identified knowledge or skill gap. In contrast, the American Board of Medical Specialties developed the Maintenance of Certification model to ensure competency for medical specialties/subspecialties. The tools to achieve these competencies include lifelong learning and self-assessment.13 Similarly, BPS could consider devising a strategy to encourage pharmacists to complete relevant and usable educational activities for recertification. This could include developing a plan with personalized learning objectives and activities to complete those objectives.

The IOM recommends that continuing education be self-directed, practice-based, and teach both identification of problems and application of solutions.11 Such continuing education would benefit not only pharmacists, but also employers. One strategy that employers might incorporate into the work environment is the Individual Development Plan (IDP). An IDP is a structured plan, written by the employee, to manage their professional development. It contains specific goals and objectives, activities, needed resources and support, and measures of success.14 Such a plan can be developed alongside a manager, but it is not intended to be a part of a performance review or driven by management. Individual development plans should be actively managed to accomplish objectives. If employers allowed pharmacists to complete their IDPs during work time, IDPs could help overcome the barriers of both time and external motivation.

Another source of external motivation could be longitudinal CPD sessions or follow-up of CPD objectives, like those utilized during the CPD trial. By reinforcing the benefits of CPD, and providing scheduled time to discuss and re-address learning plans, CPD may be more routinely utilized. For many practicing pharmacists, CPD was not the modality taught or encouraged for continuing education. Practicing pharmacists may need more than one training on the CPD concept to fully embrace it as a long-term educational strategy. Teaching the CPD concept during pharmacy school is effective and, with repeated CPD training, pharmacy students improve their ability to write learning objectives.15

Our study was not without limitations. All participants were employees of a staff model health system and had access to internal CPE activities that allowed them to fulfill their state board of pharmacy continuing education requirements during work hours. However, participants were drawn from a broad range of pharmacy practice settings (eg, clinical, administration), thus increasing the generalizability among practice types. We estimated that 85 pharmacists from the original trial would participate in the sustainability survey. However, approximately 21% of the original trial participants were lost to follow-up, so, our study only had 80% power to detect a phi effect size of 0.23. Reported trends may have resulted in statistical differences if a larger number of pharmacists had participated in the sustainability survey. Due to the novelty of this research, there is no validated instrument to assess the sustainability of CPD. The questionnaire used in the study was the only available tool previously used to assess CPD. Finally, the outcomes of the study were based on subjective perceptions reports by participants. No objective practice outcomes were assessed. Such outcomes should be addressed in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The 3-year sustainability of a CPD intervention among pharmacists was limited. CPD-trained pharmacists reported utilizing CPD concepts at a higher rate than pharmacists who had no CPD training, but there was still decay in CPD use among the former over time. Future research should examine if external motivation and protected time can improve the sustainability of benefits from CPD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; 1997. Continuing professional development: the IPD policy; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouse MJ. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61:2069–2076. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.19.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McConnell KJ, Newlon CL, Delate T. The impact of continuing professional development versus traditional continuing pharmacy education on pharmacy practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(10):1585–1595. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnell KJ, Delate T, Newlon CL. Impact of continuing professional development versus traditional continuing pharmacy education on learning behaviors. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(6):742–752. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legreid Dopp A, Moulton J, Rouse MJ, Trewet C. A five-state continuing professional development pilot program for practicing pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj740228. Article 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schichtel M, Rose PW, Sellers C. Educational interventions for primary healthcare professionals to promote the early diagnosis of cancer: a systematic review. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(4):274–290. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2013.11494186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horsley T, O’Neill J, McGowan J, Perrier L, Kane G, Campbell C. Interventions to improve question formulation in professional practice and self-directed learning. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12(5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007335.pub2. CD007335. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007335.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng GY. Educational workshop improved information seeking skills, knowledge, attitudes and the search outcome of hospital clinicians: a randomized controlled trial. Health Info Lib J. 2003;20(Suppl 1):22–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.20.s1.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donyai P, Herbert RZ, Denicolo PM, Alexander AM. British pharmacy professionals’ beliefs and participation in continuing professional development: a review of the literature. International J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(5):290–317. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tofade TS, Hedrick JN, Dedrick SC, Caiolo SM. Evaluation of pharmacist continuing professional development portfolios. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(3):237–247. doi: 10.1177/0897190012452311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2009. Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Board of Pharmacy Specialties. 2013 WHITE PAPER. Five‐Year Vision for Pharmacy Specialties. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Board of Medical Specialties. http://www.abms.org/Maintenance_of_Certification/ABMS_MOC.aspx. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- 14.Clifford PS, Fuhrmann CN, Lindstaedt B, Hobin JA. An individual development plan will help you get where you want to go. Physiologist. 2013;56(2):43–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tofade T, Khandoobhai A, Leadon K. Use of SMART learning objectives to introduce continuing professional development into the pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(4):68. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]