Abstract

We report our recent efforts directed at improving high-field DNP experiments. We investigated a series of thiourea nitroxide radicals and the associated DNP enhancements ranging from ε = 25 to 82 that demonstrate the impact of molecular structure on performance. We directly polarized low-gamma nuclei including 13C, 2H, and 17O using trityl via the cross effect. We discuss a variety of sample preparation techniques for DNP with emphasis on the benefit of methods that do not use a glass-forming cryoprotecting matrix. Lastly, we describe a corrugated waveguide for use in a 700 MHz / 460 GHz DNP system that improves microwave delivery and increases enhancements up to 50%.

Keywords: DNP, NMR, cross-effect, radicals, polarizing agent, cryoprotection

Introduction

During the past two decades, magic-angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy has emerged as an excellent analytical method to determine atomic-resolution structures in various chemical systems including pharmaceuticals,1–3 membrane proteins,4–8 amyloid fibrils,9–12 and oligomers.13, 14 Unfortunately, NMR sensitivity is inherently low and consequently many experiments require long acquisition times to achieve adequate signal-to-noise. A promising route to increase NMR sensitivity is via dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP), which seeks to polarize nuclear spins using electron polarization transferred via microwave irradiation of electron-nuclear transitions. In particular, the method has been shown to provide increases in polarization upwards of 2 to 3 orders of magnitude.15–21

Dynamic nuclear polarization was initially demonstrated in the 1950s at low magnetic fields. Following the groundbreaking work of Overhauser,22 Carver, and Slichter,23 various polarization-transfer mechanisms in solids were studied in the 1960s and 1970s and termed the solid effect (SE),24–26 the cross effect (CE),27–31 and thermal mixing (TM).19, 32–35 However, the theoretical understanding of the DNP mechanisms suggested limited applicability at magnetic fields beyond 1 T. This was followed by a brief exploration of applications of DNP to polymers at low fields (1.4 T) by Wind et al.19 and, Schaefer and co-workers.36, 37 Moreover, DNP experiments at higher fields (≥ 5 T) were hindered by the lack of stable, high-power microwave devices operating at the necessary high frequencies (e.g., 100 to 600 GHz) and also by the absence of low-temperature, high-resolution MAS NMR probes that offer both effective microwave coupling as well as the required sample cooling. Together these barriers prevented DNP from being widely applicable in the decades following its discovery. In the early 1990's, the Francis Bitter Magnet Laboratory at MIT (MIT-FBML) introduced high frequency gyrotron (a.k.a. cyclotron resonance maser) sources to magnetic resonance and DNP in particular since they can reliably provide high-frequency microwaves.38 They have now made high-field DNP viable for many applications. Combined with the improved resolution offered with higher-field MAS experiments, DNP can now be used to investigate many chemically challenging systems and areas of NMR spectroscopy including biological solids39–46, surface chemistry21, 47–49, and systems involving difficult NMR-active nuclei (e.g., low natural abundance, low gamma and / or quadrupolar nuclei).50–57

The DNP mechanism involves microwave irradiation of the EPR transitions of a paramagnetic polarizing agent that transfers the large spin polarization of electrons to nearby nuclei. In order to accomplish this at contemporary NMR fields (i.e., 200 to 1000 MHz), three criteria must be met: i.) a stable high-frequency microwave source (≥ 102 GHz), ii.) a reliable cryogenic MAS probe with adequate microwave waveguide delivery, and iii.) a suitable polarizing agent for the sample under study. The first criterion was met by the aforementioned gyrotrons, which are fast wave devices that can deliver the appropriate frequency range for stimulation of the EPR transitions at high fields, and they can be operated stably and continuously over an extended period of time (i.e., weeks to months), delivering output power up to 25 W.58 Alternative to gyrotrons, DNP can also be performed at helium cooled temperature (< 70 K) using a low-power (~ 30 – 200 mW) diode microwave source that tunes to the appropriate frequency.59 Second, to date DNP is optimally performed at cryogenic temperatures to decrease electron and nuclear relaxation rates in order to increase the obtainable non-Boltzmann polarization. To achieve the desired temperature (80–100 K) typically requires a specially designed heat exchanger / dewar system,60 vacuum-jacketed gas-transfer lines, and optional pre-chillers.61, 62 The complexity of this instrumentation is further compounded by the need for MAS in order to obtain high resolution spectra, meaning that carefully designed and constructed multichannel (e.g., 1H/13C/15N/e−) low-temperature MAS NMR probes are essential.63 The third requirement is the availability of paramagnetic species (polarization agents) that are the polarization source for various chemical systems. The polarizing agent can be exogenous or endogenous and most often comes in the form of a free radical. It should be compatible with the chemical system (e.g., non-reactive), able to yield large DNP enhancements, and chemically robust. Depending on the application, the radicals and experimental conditions can be developed to optimize a specific DNP mechanism64, 65 such as SE or CE.

Over the past two decades, development of high-field DNP has focused primarily on using the CE mechanism, since the typical SE enhancements had been considerably lower because it relies on irradiation of forbidden transitions.66 Below we make mention of both the SE and CE mechanism as recent results have shown that the SE may be useful for polarization using transition-metal based polarizing agents67 and recently has been observed to provide significant enhancements at approximately 100.68, 69 Furthermore, with the continued development of equipment producing increased microwave field strengths, the enhancements and sensitivity may match those of CE.70 The dominant polarization transfer process (SE or CE) depends on the NMR-active nuclei being polarized and also the EPR characteristics of the specific polarizing agent. Particularly, the relative magnitudes of the electron homogeneous (δ) and inhomogeneous (Δ) linewidths, and the nuclear Larmor frequency (ω0I) are the most important factors to determine the dominant polarization mechanism.

The SE mechanism, shown in Scheme 1, is a two-spin process which is dominant when ω0I > δ, Δ and microwave irradiation is applied at the electron-nuclear zero- or double-quantum transition.25, 26, 68, 69 This matching condition is given by:

| (1) |

where ω0S is the electron Larmor frequency and ωmw is the microwave frequency. For SE, since the microwave frequency required must match the condition given in Eq. (1), a polarizing agent with a narrow EPR spectrum is typically used, with an electron T1S that is optimized to allow efficient polarization of nearby nuclei without introducing large signal quenching.

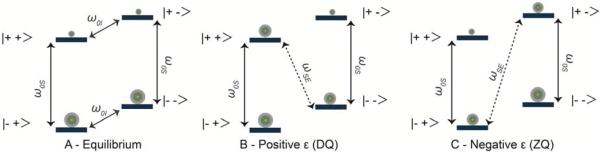

Scheme 1.

Spin population distribution for a two-spin (1 electron and 1 nucleus) system at thermal equilibrium (A). SE conditions for the positive, ω0S − ω0I (B) and negative enhancement, ω0S + ω0I (C).

The CE mechanism may be described as a three-spin flip-flop-flip process between two electrons and a nucleus, which is dominant when Δ > ω0I > δ. In order to achieve maximum efficiency, the difference between the two electron Larmor frequencies must be near the nuclear Larmor frequency.27, 29, 71, 72

| (2) |

For CE73, a radical with a broad EPR linewidth, particularly a nitroxide based radical, is often used to satisfy the condition provided in Eq. (2). CE is often the choice for high-field DNP experiments due to this mechanism being based on allowable transitions unlike the SE. Scheme 2 shows the energy level diagram for the CE mechanism.

Scheme 2.

Spin population distribution for a three-spin (2 electrons and 1 nucleus) system at thermal equilibrium with the NMR transitions marked (A). The CE condition for the negative (B) and positive (C) enhancement. Microwave saturation of the electron transition (ω0S1 or ω0S2) leads to a three-spin flip-flop-flip process that distributes the population (ωCE), thus increasing the net nuclear polarization.

The descriptions for the SE and the CE DNP mechanism, vide supra, do not incorporate sample rotation. That is, the effects of MAS on modulating energy levels that create level crossings and impact polarization transfer. Recently, Thurber and Tycko74 and Mentink-Vigier et al.75 discussed the CE mechanism in MAS, showed experimental MAS DNP NMR data on the SH3 protein and described theoretical models of the effect MAS has on both the CE and the SE mechanism.

In this paper, we provide a brief overview of recent developments in high-field DNP at the MIT-FBML, including polarizing agents, sample preparation methods, and improvements to the 700 MHz / 460 GHz DNP spectrometer.

i. Development of CE Biradicals

Nitroxide monoradicals (e.g., TEMPOL) were popular in early high-field DNP experiments. They are suited for CE DNP of 1H because the breadth of the EPR spectrum is on the order of ~600 MHz at 5 T.76 They are also low-cost, commercially available, highly water-soluble, and offer reasonable DNP enhancements between ε = 20 to 50.38, 77 For these monoradicals, a concentration of up to 40 mM usually provides the best signal enhancements. However, at these elevated electron concentrations, paramagnetic relaxation strongly competes with DNP enhancement and only provides moderate electron-electron dipolar couplings between 0.2 to 1.2 MHz. Increasing the concentration of radical (i.e., beyond 40 mM electrons) further is unsuitable for high-resolution NMR work because of line broadening and signal quenching effects at these higher radical concentrations.78–80

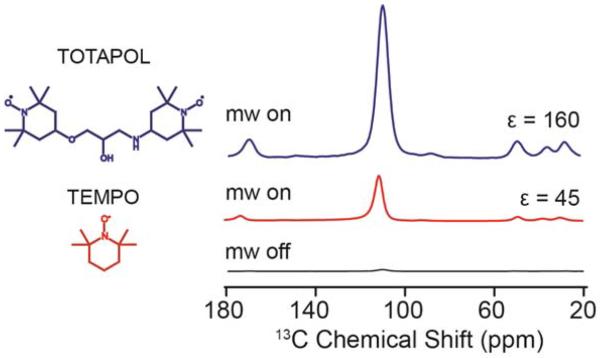

To improve the CE efficiency, biradicals were introduced for DNP in order to improve the electron-electron dipolar coupling critical to CE DNP while lowering the overall radical concentration to minimize paramagnetic effects (i.e., signal quenching and broadening). By tethering two TEMPO monoradicals, one such biradical, TOTAPOL,81 has an effective electron – electron coupling of ~ 26 MHz, is water-soluble, and provides greater 1H enhancements than TEMPO based monoradicals by nearly four-fold at 5 T as shown in Figure 1. The discovery of TOTAPOL as a polarization agent and the then-unprecedented signal enhancements it produced belies the extreme sensitivity of the CE efficiency to molecular perturbations. Tethering nitroxide radicals introduces several parameters that can be optimized, and synthetic organic chemistry is the primary tool of modulating dipolar coupling (i.e. inter-electron distance), g-tensor orientation, water solubility, and relaxation behaviors. All of these factors impact the resulting DNP signal enhancement. The large synthetic opportunity has led us and others to pursue new generations of biradicals in order to achieve even greater DNP enhancements.82–86

Figure 1.

13C{1H} cross-polarization of 13C-urea in a 60/30/10 v/v d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O with 20 mM TOTAPOL (top, 1H DNP) and 40 mM TEMPO (bottom, 1H DNP) acquired at 140 GHz / 212 MHz DNP NMR spectrometer with 8 W of microwave power, 4.5 kHz MAS, and 16 scans (on-signal) and 256 scans (off-signal).

Here we examine a series of biradicals that are structural variants of bT-thiourea to illustrate the impact of molecular structure upon DNP enhancement. The bT-thioureas were synthesized to improve aqueous solubility exhibited by bT-urea73, but they have a lower enhancement as shown in Figure 2. The reason for this reduction in obtainable signal enhancement from bT-urea to bT-thiourea (bT-thio-3) may be due to a compression of the TEMPO moieties from the increased steric bulk stemming from the sulfur (as opposed to oxygen) in the thiourea, or alternatively it may be due to an undesirable gain in torsional mobility upon switching the urea group to a thiourea group. We observed a further loss of DNP enhancement upon utilizing the bT-thionourethane (bT-thio-2) biradical. The increased conformational flexibility of the bT-thionourethane may be deleterious in that the only other conformation available to this molecule (versus BT-thiourea) features the oxygen-bound TEMPO moiety beneath the thionourethane linker. This would result in a reduced inter-electron distance similar to other highly-coupled biradicals.73 Nevertheless, it should be noted that increasing conformational flexibility is not always deleterious. bT-thionocarbonate (bT-thio-1) is the most conformationally flexible structural variant studied, and it shows a larger enhancement than bT-thionourethane. The slightly preferred s-trans orientation of thionocarbonates is apparently more than enough to compensate for the modestly diminished inter-electron distance resulting from the shorter C-O (vs. C-N) bonds, therefore producing a DNP enhancement similar to that of bT-thiourea (BT-thio-3).

Figure 2.

13C{1H} cross-polarization spectra of 13C-urea in DMSO/D2O/H2O (60:30:10, v/v) and 10 mM biradical polarizing agent (20 mM electrons) acquired at 140 GHz / 212 MHz DNP NMR spectrometer with 8 W of microwave power. 1H DNP enhancements were scaled with respect to TOTAPOL using three thiourea variants. From top to bottom five radicals were studied including TOTAPOL (black), BT-urea (red), BT-thio-1 (thionocarbonate, grey), BT-thio-2 (BT-thionourethane, blue) and BT-thio-3 (BT-thiourea, green). The spectra inset are the on/off 13C{1H} CPMAS spectra scaled to the TOTAPOL enhancement in DMSO/water mixture.

The study of the bT-thiourea-based radicals highlights the multi-dimensional problem of developing radicals for DNP. As the study continues, more effective radicals will be discovered for DNP application to different chemistry problems. For example, many biradicals currently are optimized for dissolution in cryoprotectants such as glycerol/water or DMSO/water for studying biological samples at cryogenic temperatures.81, 82 The glassing behavior of cryoprotectants disperses the radical homogeneously throughout the sample and allows uniform polarization. Amongst organic solids, some systems have meta-stable amorphous phases such as the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin,87, 88 but they may not be miscible with existing biradicals such as TOTAPOL for effective DNP experiments. For this reason, we used the organic biradical bis-TEMPO terephthalate (bTtereph) for our DNP study on amorphous ortho-terphenyl and amorphous indomethacin.89 We found that the biradical exhibits similar EPR and DNP profiles as TOTAPOL (Figure 3) and can be incorporated uniformly within amorphous ortho-terphenyl and indomethacin samples without needing other glassing agents.

Figure 3.

bTtereph synthetic process (a) and resulting 140 GHz EPR spectrum (b) and 1H DNP field (c) profile of 10 mM bTtereph incorporated in 95% deuterated amorphous ortho-terphenyl.

More recently, a new truxene-based radical, TMT, was found to be persistent, having a half-life (t1/2) of 5.8 h in a non-aqueous solution exposed to air.90 EPR at 140 GHz shows a g-value very close to that of BDPA91 and a linewidth of 40 MHz (Figure 4). The radical may be ideal for supporting the CE, either alone for low-γ nuclei such as 15N, or as part of a biradical or radical mixture with Trityl OX063 or TEMPO.66, 92 Current work is aimed at increasing the radical's solubility in aqueous solvent mixtures suitable for DNP of biological samples and improving its stability under ambient conditions.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures and 140 GHz EPR spectra of three narrow-line radicals: (a) Trityl (OX063), (b) TMT, and (c) SA-BDPA.

ii. Direct Polarization of Low-Gamma Nuclei using Trityl

Currently, the conventional wisdom is that the most efficient electron-nuclear transfer mechanism in the solid state is the CE. Consequently, many polarization agents are designed from nitroxide based radicals due to their broad EPR profile easily satisfying the CE match condition in Eq. (2) for 1H. For many systems, polarizing 1H (indirect polarization) by CE is an effective method because 1H typically have shorter relaxation times, which enables rapid signal averaging as well as offers additional gains by means of cross-polarization to other low-gamma nuclei that are often less abundant. However, direct polarization of low-gamma nuclei is also of interest considering the theoretical maximum DNP enhancement is given by the ratio γe/γI,19, 42, 54, 55, 57, 92–94 and the technique would offer a significant sensitivity boost for chemical systems that cross-polarize poorly, or where high-Ɣ nuclei (i.e., 1H, 19F, etc.) are absent. Focusing on the five most common nuclei used in biomolecular NMR, three of them have I=1/2 (i.e., 1H, 13C and 15N) while 2H has I=1 and 17O has I=5/2. With the exception of 1H, these nuclei are low-gamma and low natural abundance (Table 1). Moreover, the latter two nuclei are quadrupolar and consequently experience additional line broadening brought about by the interaction between the intrinsic electric quadrupole moment and the electric field gradient (EFG) generated by the surrounding environment, thereby giving rise to quadrupolar coupling. This additional interaction negatively impacts NMR sensitivity because the quadrupolar coupling constant covers a spectral range from tens of kHz up to a few MHz. With these factors in mind, DNP experiments that directly polarize low-gamma and/or quadrupolar nuclei can potentially be useful and open new possibilities for high field DNP.

Table 1.

Physical properties for selected biologically relevant NMR nuclei.

| NMR Active Isotope | N.A. (%) | Magnetogyric Ratio (MHz / T) | Sensitivity Relative to 1H | Theoretical Σmax(Ɣe/Ɣn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 99.99 | 42.57 | 1 | 658 |

| 13C | 1.07 | 10.71 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 2616 |

| 2H | 0.01 | 6.53 | 1.11 × 10−6 | 4291 |

| 17O | 0.037 | 5.77 | 1.11 × 10−5 | 4857 |

For the direct polarization experiments, we can utilize radicals with narrower lines than needed to polarize protons by CE but still able to satisfy the CE match condition of low-gamma nuclei. The water-soluble narrow-line monoradical trityl(OX063)95, 96 with its EPR spectrum is depicted in Figure 4. The EPR spectrum is considerably narrower than that of the common nitroxide based radicals, with a linewidth of approximately 50 MHz at 5 T.55, 92, 97 This narrow profile creates the possibility for both SE and/or CE mechanism to contribute to the DNP enhancement depending on the targeted nucleus. In order to determine the effectiveness of trityl on three low-gamma nuclei (i.e., 13C, 2H, and 17O), a series of DNP experiments were attempted, followed by the characterization of the mechanisms with assistance from the DNP field profiles (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Direct polarization of 13C (circle, blue), 2H (diamond, red) and 17O (triangle, grey) field profiles acquired at 5 T using 40 mM Trityl radical. 140 GHz EPR spectrum of trityl (black, top) with the appropriate SE matching conditions illustrated with the corresponding colored dashed lines.

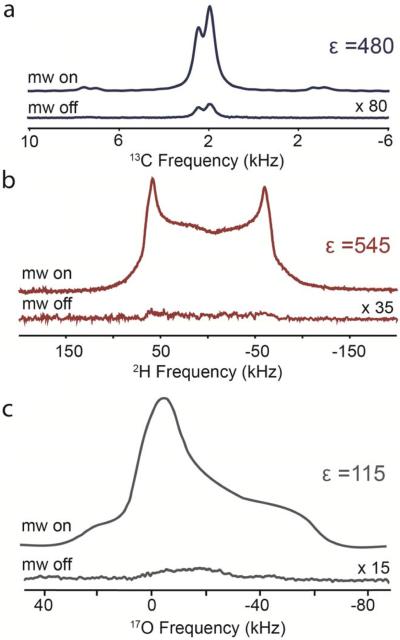

For direct polarization of 13C, we obtained an enhancement of 480 (Figure 6a) using trityl, which is nearly 180% larger than using TOTAPOL.92, 94 Examining more closely at the positive and negative maxima of the DNP profile, we can see there is a clear asymmetry (i.e., −380 vs. 480) present. However, unlike the 1H field profile of trityl68 there is no feature in the center of the profile between the two maxima. This suggests that CE polarization mechanism is making some contribution to the DNP mechanism. Nevertheless, the nuclear Larmor frequency of 13C is slightly larger than the breadth of the trityl EPR spectrum at 5 T, and therefore by definition the SE must be considered. Looking at the positive and negative maxima of the 13C DNP field profile, the positions are in remarkably good agreement (Figure 5, blue dotted lines) with those predicted for the SE mechanism, suggesting a significant contribution.

Figure 6.

Direct polarization of low-gamma nuclei using 40 mM trityl on (a) 13C (νL = 53 MHz), (b) 2H (νL = 32 MHz) and (c) 17O (28 MHz) in a glycerol/water cryoprotectant. DNP enhanced signals were acquired using 8 W of CW microwave power with the magnetic field set to the optimum field position (positive) shown in Figure 5.

The nuclear Larmor frequencies of 2H and 17O are separated by only ~ 4 MHz at 5 T and appear to behave similarly as the field profiles are nearly overlapping. Although the electron inhomogeneous linewidth of the trityl radical is small, it is still large enough to satisfy the CE match condition for both nuclei. Both field profiles do not exhibit resolved features at frequencies corresponding to ω0S ± ω0I (Figure 5, red and grey lines), which assures that the CE mechanism is dominant for both 2H and 17O. For static DNP experiments acquired at 85 K, the 2H and 17O enhancements are 545 and 115, respectively (Figure 6b and 6c). This makes trityl still one of the most effective radicals to polarize such nuclei under MAS and static conditions.54, 55, 98 The EPR spectrum is nearly symmetric which gives rise to the nearly symmetric positive and negative maxima in the DNP field profile. The smaller enhancement for 17O may be attributed to the comparably short polarization build-up time constant (TB = 5.0 ± 0.6 s) inhibiting saturation. This suggests a relatively fast nuclear relaxation rate that inhibits the build-up of non-Boltzmann polarization. In the case of 2H and 13C, both nuclei exhibit larger DNP gains and both have longer TB (Table 2). The large quadrupolar coupling of 17O may also be a factor, and studies are currently underway to elucidate this. We would also like to note that for all of these nuclei studied the trityl EPR line was not saturated by using 8 W of microwave power, and further enhancement gains should be possible by increasing the available microwave power.

Table 2.

Direct polarization of various biologically relevant nuclei using trityl at 5 T.

| Nucleus | ε (positive) (± 10%) | ε (negative) (± 10%) | TB (s) | ω0I/2π (MHz) | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H68 | 90 | −81 | 22 | 212.03 | SE |

| 13C92 | 480 | −380 | 225 | 53.3 | CE/SE |

| 2H | 545 | −565 | 75 | 32.5 | CE |

| 17O54 | 115 | −116 | 5.5 | 28.7 | CE |

iii. Sample Preparation Techniques

The effective DNP polarization of a biological solid requires a few key criteria to be met. The first is to disperse the polarizing agent, which allows uniform polarization across the whole sample followed by effective spin-diffusion. For biological samples such as membrane proteins, amyloid fibrils, and peptides, a cryoprotecting matrix such as glycerol/water or DMSO/water, which forms an amorphous “glassy” state at low temperatures to protect the sample against freezing damage, can be used to homogeneously disperse the polarizing agent for DNP. Labeling of the cryoprotecting matrix, in particular D2O, deuterated glycerol, and deuterated DMSO, can be used to fine tune 1H-1H spin-diffusion to optimize the obtainable DNP enhancement, while reverse labeling the matrix (e.g., 12C-glycerol) can minimize solvent background. In our experience, a cryoprotecting matrix that is heavily deuterated is optimal for DNP, and typically we prepare our samples in a 60/30/10 v/v d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O. However, the NMR of a homogeneous, amorphous chemical system can be limited in resolution due to line-broadening stemming from a distribution of chemical shift, a commonly observed occurrence for many organic and inorganic amorphous materials, as well as from slower side-chain dynamics at cryogenic temperatures. Despite this limitation, DNP has been successfully applied to heterogeneous systems like the membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin15, 39, 40, 58, 99 and M2100, and by combining with methods including specific labeling101–103 and crystal suspension in liquid41, 47, 48, 104, 105. DNP NMR also has been demonstrated on various chemical systems without adding a cryoprotectant, due to either thermal stability or self-cryoprotecting ability.45, 89, 106–108

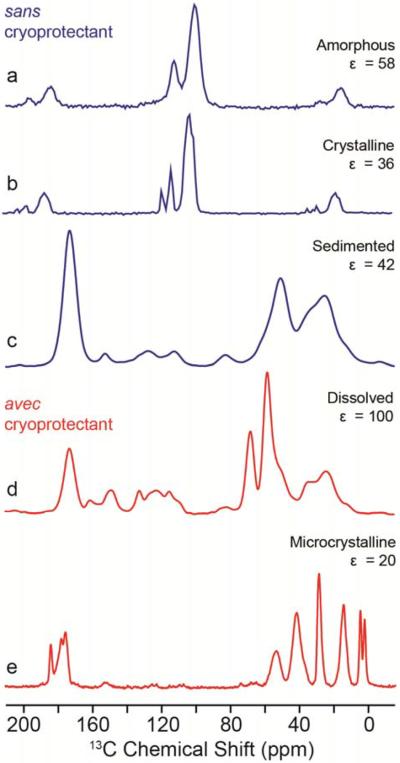

Figure 7 illustrates the various sample preparation methods both with and without cryoprotecting matrix. Figure 7a and b show DNP of amorphous and crystalline 95% deuterated ortho-terphenyl. While both samples show large 1H DNP enhancements, the crystalline sample has somewhat improved resolution of the various 13C resonances. The resolution as described above is not impacted by temperature, but by the distribution in chemical shift brought about by the formation of a disordered homogeneous solid. Figure 7c and d show DNP enhanced spectra of apoferritin complex (480 kDa) prepared using either a traditional glycerol/water cryoprotectant (Figure 7d) or the new sedimentation method (SedDNP) (Figure 7c) where the amount of free water is significantly reduced109, 110 either by ultracentrifugation (ex situ)107, 111–113 or via fast magic angle spinning (in situ).106, 114, 115 Either sedimentation method results in a “microcrystalline” glass that effectively distributes the polarizing agent within the sample, allows efficient spin diffusion through the whole sample, and protects against potential damage from ice crystal formation. Both approaches provide high sensitivity, however the sedimentation method minimizes the solvent present and so reduces the solvent resonances (e.g., glycerol at ~60–70 ppm) while improving the overall filling factor when using the ex situ method. The sedimentation technique has an added advantage where cooling to cryogenic temperatures and employing DNP can offer additional structural information and constraint not observed at experiments performed at ambient condition. The low temperature spectra can provide extensive information on side chain motion and details concerning aromatic regions that are often lost due to decoupling interference at room temperature.101, 116

Figure 7.

MAS DNP sample preparation protocols for biophysical systems. Without cryoprotecting solvents (sans) include distributing a polarizing agent within the organic solid: amorphous (a) or crystalline (b) 95% deuterated ortho-Terphenyl (OTP) with 0.5 mol% bTtereph or using the SedDNP approach, U-13C,15N-Apoferritin (2 mM TOTAPOL) (c). Alternative is distributing the radical in a cryoprotecting solvent (avec) homogenously, U-13C,15N-Apoferritin in d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (v/v 60/35/5) and 15 mM TOTAPOL (d) or heterogeneously using microcrystals, [U-13C,15N GNNQ]QNY in d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (w/w 70/23/7) and 35 mM TOTAPOL (e).

Finally, nanocrystalline preparation of GNNQQNY104, 117 (Figure 7e) by suspension in a cryoprotecting matrix provides high resolution and DNP enhancement for structural understanding in both crystalline and amyloid forms. Wetting of microcrystals has also been attractive for the study of various surface science questions whereby a nitroxide biradical is dispersed into an organic solvent and added to the crystalline material of choice prior to cooling.47–49 Furthermore, a solvent-free dehydration approach whereby the radical is placed onto the system such as glucose or cellulose, followed by evaporation has also recently shown promise for natural abundance systems.45, 108 Although these methods lead to a more heterogeneous distribution of radicals and hence polarization is not uniform within the samples, they maintain excellent sensitivity and produce excellent spectral resolution from an overall smaller effect from paramagnetic broadening.

iv. Improving DNP Instrumentation at High Fields (≥ 16 T)

In recent years, high-field DNP has evolved beyond 9.4 T (400 MHz, 1H). The innovation in gyrotron technology has led to more adoptions of high-field DNP spectrometers such as the 600 MHz / 395 GHz62, 118 (Osaka University, Japan and University of Warwick, UK), the 700 MHz / 460 GHz61 (MIT, Cambridge, MA), and the commercial 600 MHz/ 395 GHz and 800 MHz / 527 GHz from Bruker Biospin. However, DNP theory predicts the experiment to be less effective at high fields, with an inverse scaling of CE DNP and an inverse-squared scaling of SE DNP enhancement with respect to increasing magnetic field.71 This is because the inhomogeneous EPR linewidth of the polarizing agent increases proportionally with respect to the magnetic field (Δ ∝ Bo), meaning that the CE matching condition becomes harder to satisfy. The challenge is compounded by the difficult tasks of maintaining effective cooling capabilities at elevated MAS frequencies (e.g., limiting frictional heating) and also coupling gyrotron microwaves to the NMR sample. Therefore, considerable effort has been made to improve instrumentation in order to gain reasonable DNP enhancement at these fields. Given the inherent better resolution of high field NMR (vide infra), successful DNP can become a valuable approach to obtain structural information on challenging biological samples.

One particular difficulty in implementing DNP at higher magnetic fields is the transmission of high-power microwaves from the gyrotron to the sample with minimal loss. This can be achieved by using corrugated overmoded waveguides, which are more efficient than the previously used fundamental mode waveguides, to minimize mode conversion and ohmic loss. At the MIT-FBML, the microwave source of the 700 MHz DNP system is a 460 GHz gyrotron operating in the second harmonic, in a TE11,2 mode.119 The produced microwaves are guided through a ~ 465 cm long, 19.05 mm inner diameter (i.d.) corrugated waveguide that connects the 16.4 T NMR magnet and the 8.2 T gyrotron magnet. The alignment is critical to maintain a clean microwave mode with minimum energy loss through the long waveguide, and we were able to achieve less than 1 dB loss from the gyrotron window to the final miter-bend that directs the microwaves into the probe body. The final ~107 cm of the waveguide is located within the NMR probe, and it was initially constructed by a series of down tapers reducing the i.d. from 19.05 to 4.6 mm. using a combination of smooth-walled macor, aluminum and copper waveguide portions. However, due to the significant loss of microwave power associated with 4.6 mm waveguide and macor sections at 460 GHz (λ = 0.65 mm), several changes were implemented to improve microwave transmission to the sample. A newly designed waveguide for our home-built DNP NMR probes now includes a modified tapered and corrugated aluminum waveguide section from 19.05 to 11.43 mm i.d. at the base of the NMR probe (Figure 8), and at which point the microwaves are directed toward the stator via a 45° miter-bend. The microwaves are then reflected off a copper mirror into a multi-section corrugated waveguide with an 11.43 mm i.d. consisting of a stainless steel section at the base which acts as a thermal break followed by two copper sections. The final 50 mm portion approaches the reverse magic-angle microwave beam launcher and features an aluminum corrugated part that is tapered from 11.43 to 8 mm i.d. in order to direct and focus the microwave beam into the 3.2 mm MAS stator housing. A small Vespel® washer is installed prior to the final taper to act as an electrical break between the microwaves and the RF. Finally, the waveguide is terminated by a copper microwave launcher at the reverse magic-angle, and aligned using three brass set screws. With these modifications, the new probe waveguide design reduces the loss of microwave power being transmitted to the sample while maintaining the effective Gaussian beam content. The new design has improved the high-field DNP enhancements by 40–50%, from −38 (4) to −53 (5) on a sample of 1 M 13C-urea at 80 (2) K with MAS frequency of 5.2 kHz, and from −21 to −33 on a sample of 0.5 M U-13C-proline with MAS frequency of 9.2 kHz. Figure 9 shows a DNP enhanced 13C-13C DARR spectrum of U-13C-proline that illustrates the good resolution and sensitivity gain that can be achieved with high field DNP.

Figure 8.

Artistic rendering of the new waveguide designed for the 460 GHz / 700 MHz DNP NMR spectrometer (FBML-MIT). The inset is an 13C{1H} cross-polarization MAS spectrum (mw on/off) of 1M 13C-Urea in d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (v/v 60/30/10) with 10 mM TOTAPOL and packed into a 3.2 mm sapphire rotor, acquired at 80 K and a spinning frequency of 5.2 kHz. Abbreviations: copper (Cu), aluminum (Al) and stainless steel (SS).

Figure 9.

(A) 13C-13C DARR spectrum of U-13C-Proline (0.5 M) in d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (v/v 60/30/10) with 10 mM TOTAPOL (1H enhancement of 33 (3)) using a 20 ms DARR mixing period. (B) An enlarged aliphatic and carbonyl region illustrating the connectivity of U-13C-Proline. Sample was packed into a 3.2 mm sapphire rotor, data was acquired with 8 scans, rd = 20 s, 64 increments, 11 W of microwave power, sample temperature 82 (2) K and a spinning frequency of 9.2 kHz.

We recently used the improved 700 MHz/460 GHz DNP system to study apoferritin, which is an important protein for maintaining available non-toxic soluble forms of iron in various organisms.120, 121 Apoferritin, the iron-free form, is a 480 kDa globular protein complex consisting of 24 subunits, with each unit being 20 kDa in size. The protein is a challenging system for NMR122, 123 due to its large size comprised of nearly 4,000 residues.124 Nevertheless, chemical shift separation can be achieved at higher magnetic fields, and structural insight can be gained through a combination of approaches including solution and solid-state methods (i.e., SedNMR)115, 122, 123 as well as combining with DNP (i.e., SedDNP).106 Figure 10 is an overlay of U-13C,15N-apoferritin collected at 212 MHz / 140 GHz and 697 MHz / 460 GHz employing a 13C-13C PDSD dipolar recoupling experiment. Although the DNP enhancement is lower (partially attributed to acquiring our data at the negative side of the TOTAPOL field profile, figure 2) at the higher field (ε = −6, with ε† = −21 accounting for Boltzmann population difference between cryogenic and room temperature, defined as ε† = ε(TRT/TDNP)) compares to the lower field enhancement (ε = 42), we can see that the aliphatic region is significantly more dispersed in the higher field spectrum enabling differentiation between the Cα and Cβ region. Continuing effort at improving instrumentation and developing new radicals will potentially increase enhancement further than what is currently obtainable.

Figure 10.

13C-13C correlation spectrum of U-13C,15N-apoferritin at 5 T (green, ωr/2π = 4.8 kHz, T = 82 K, mw = 9 W) and 16.4 T (blue, ωr/2π = 8.8 kHz, T = 87 K, mw = 10 W) using DNP MAS NMR.

Conclusion

In this topical review, we discussed the recent DNP efforts at MIT-FBML including new radical polarization-agent development, direct polarization of low-gamma nuclei, various sample preparation methods, and hardware improvements to the MIT-FBML 700 MHz / 460 GHz DNP NMR spectrometer. As developmental efforts continue and along with the recent commercialization of DNP systems, we foresee the method achieving greater sensitivity for NMR and becoming a more general method to study various biological and chemical systems. We expect the wider adoption of DNP to be a very fruitful endeavor leading to many new and exciting scientific discoveries.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bjorn Corzilius, Eugenio Daviso, Albert Smith, Loren Andreas, Galia Debelouchina, Jennifer Mathies, Michael Colvin, Emilio Nanni, Sudheer Jawla, Ivan Mastrovsky and Richard Temkin for helpful discussions during the course of this research. Ajay Thakkar, Jeffrey Bryant, Ron DeRocher, Michael Mullins, David Ruben and Chris Turner are thanked for technical assistance. The National Institutes of Health through grants EB002804, EB003151, EB002026, EB001960, EB001035, EB001965, and EB004866 supported this research. This work has been supported by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, the European Commission, contract Bio-NMR no. 261863, and Instruct, part of the ESFRI, MIUR PRIN (2009FAKHZT_001) and supported by national member subscriptions. Specifically, we thank the EU ESFRI Instruct Core Centre CERM, Italy. V.K.M. acknowledges the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada for a Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

- 1.Harris RK. Applications of Solid-State NMR to Pharmaceutical Polymorphism and Related Matters*. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2007;59(2):225–239. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.2.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogt FG. Evolution of Solid-State NMR in Pharmaceutical Analysis. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;2(6):915–921. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SP. Applications of High-Resolution H-1 Solid-State NMR. Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. 2012;41:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott A. Structure and Dynamics of Membrane Proteins by Magic Angle Spinning Solid-State NMR. Annual Review of Biophysics. 2009;38:385–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreas LB, Eddy MT, Pielak RM, Chou J, Griffin RG. Magic Angle Spinning NMR Investigation of Influenza a M2(18–60): Support for an Allosteric Mechanism of Inhibition. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132(32):10958–10960. doi: 10.1021/ja101537p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cady S, Wang T, Hong M. Membrane-Dependent Effects of a Cytoplasmic Helix on the Structure and Drug Binding of the Influenza Virus M2 Protein. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(30):11572–11579. doi: 10.1021/ja202051n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddy MT, Ong TC, Clark L, Teijido O, van der Wel PCA, Garces R, Wagner G, Rostovtseva TK, Griffin RG. Lipid Dynamics and Protein-Lipid Interactions in 2d Crystals Formed with the Beta-Barrel Integral Membrane Protein Vdac1. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134(14):6375–6387. doi: 10.1021/ja300347v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi LC, Ahmed MAM, Zhang WR, Whited G, Brown LS, Ladizhansky V. Three-Dimensional Solid-State NMR Study of a Seven-Helical Integral Membrane Proton Pump-Structural Insights. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;386(4):1078–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tycko R. Solid-State NMR as a Probe of Amyloid Structure. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2006;13(3):229–234. doi: 10.2174/092986606775338470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayro MJ, Debelouchina GT, Eddy MT, Birkett NR, MacPhee CE, Rosay M, Maas WE, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. Intermolecular Structure Determination of Amyloid Fibrils with Magic-Angle Spinning and Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(35):13967–13974. doi: 10.1021/ja203756x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick AWP, Debelouchina GT, Bayro MJ, Clare DK, Caporini MA, Bajaj VS, Jaroniec CP, Wang LC, Ladizhansky V, Muller SA, et al. Atomic Structure and Hierarchical Assembly of a Cross-Beta Amyloid Fibril. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(14):5468–5473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219476110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertini I, Gonnelli L, Luchinat C, Mao JF, Nesi A. A New Structural Model of a Beta(40) Fibrils. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(40):16013–16022. doi: 10.1021/ja2035859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertini I, Gallo G, Korsak M, Luchinat C, Mao J, Ravera E. Formation Kinetics and Structural Features of Beta-Amylod Aggregates by Sedimented Solute NMR. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:1891–1987. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chimon S, Ishii Y. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:13472–13473. doi: 10.1021/ja054039l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni QZ, Daviso E, Cana TV, Markhasin E, Jawla SK, Temkin RJ, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. High Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Accounts of Chem Research. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ar300348n. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maly T, Debelouchina GT, Bajaj VS, Hu KN, Joo CG, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Sirigiri JR, van der Wel PCA, Herzfeld J, Temkin RJ, et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at High Magnetic Fields. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2008;128(5) doi: 10.1063/1.2833582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abragam A, Goldman M. Nuclear Magnetism: Order and Disorder. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atsarkin VA. Dynamic Polarization of Nuclei in Solid Dielectrics. Soviet Physics Solid State. 1978;21:725–744. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wind RA, Duijvestijn MJ, Vanderlugt C, Manenschijn A, Vriend J. Applications of Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization in C-13 Nmr in Solids. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 1985;17:33–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes AB, Paëpe GD, Wel P. C. A. v. d., Hu K-N, Joo C-G, Bajaj VS, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Sirigiri JR, Herzfeld J, Temkin RJ, et al. High Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization for Solid and Solution Biological NMR. Applied Magnetic Resonance. 2008;34:237–263. doi: 10.1007/s00723-008-0129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Lesage A, Copéret C, Emsley L. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Surface Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ar300322x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overhauser AW. Polarization of Nuclei in Metals. Physical Review. 1953;92(2):411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carver TR, Slichter CP. Polarization of Nuclear Spins in Metals. Physical Review. 1953;92(1):212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeffries CD. Polarization of Nuclei by Resonance Saturation in Paramagnetic Crystals. Physical Review. 1957;106(1):164–165. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abragam A, Proctor WG. Une Nouvelle Methode De Polarisation Dynamique Des Noyaux Atomiques Dans Les Solides. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires Des Seances De L Academie Des Sciences. 1958;246(15):2253–2256. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffries CD. Dynamic Orientation of Nuclei by Forbidden Transitions in Paramagnetic Resonance. Physical Review. 1960;117(4):1056–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessenikh AV, Lushchikov VI, Manenkov AA, Taran YV. Proton Polarization in Irradiated Polyethylenes. Soviet Physics-Solid State. 1963;5(2):321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessenikh AV, Manenkov AA, Pyatnitskii GI. On Explanation of Experimental Data on Dynamic Polarization of Protons in Irradiated Polyethylenes. Soviet Physics-Solid State. 1964;6(3):641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang CF, Hill DA. New Effect in Dynamic Polarization. Physical Review Letters. 1967;18(4):110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang CF, Hill DA. Phenomenological Model for New Effect in Dynamic Polarization. Physical Review Letters. 1967;19(18):1011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wollan DS. Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization with an Inhomogeneously Broadened Esr Line .1. Theory. Physical Review B. 1976;13(9):3671–3685. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman M. Spin Temperature and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in Solids. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1970. p. ix.p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duijvestijn MJ, Wind RA, Smidt J. A Quantitative Investigation of the Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization Effect by Fixed Paramagnetic Centra of Abundant and Rare Spins in Solids at Room-Temperature. Physica B & C. 1986;138(1–2):147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenckebach WT, Swanenburg TJB, Poulis NJ. Thermodynamics of Spin Systems in Paramagnetic Crystals. Physics Reports. 1974;14(5):181–255. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borghini M, Boer WD, Morimoto K. Nuclear Dynamic Polarization by Resolved Solid-Effect and Thermal Mixing with an Electron Spin-Spin Interaction Reservoir. Physics Letters. 1974;48A(4):244–246. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Afeworki M, McKay RA, Schaefer J. Selective Observation of the Interface of Heterogeneous Polycarbonate Polystyrene Blends by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization C-13 NMR Spectroscopy. Macromolecules. 1992;25:4048–4091. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afeworki M, Vega S, Schaefer J. Direct Electron-to-Carbon Polarizaiton Transfer in Homogeneously Doped Polycarbonates. Macromolecules. 1992;25:4100–4105. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becerra LR, Gerfen GJ, Bellew BF, Bryant JA, Hall DA, Inati SJ, Weber RT, Un S, Prisner TF, Mcdermott AE, et al. A Spectrometer for Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization and Electron-Paramagnetic-Resonance at High-Frequencies. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series A. 1995;117(1):28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Bajaj VS, Hornstein MK, Belenky M, Griffin RG, Herzfeld J. Energy Transformations Early in the Bacteriorhodopsin Photocycle Revealed by DNP-Enhanced Solid-State NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(3):883–888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706156105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bajaj VS, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Belenky M, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Functional and Shunt States of Bacteriorhodopsin Resolved by 250 GHz Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced Solid-State NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(23):9244–9249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900908106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debelouchina GT, Bayro MJ, van der Wel PCA, Caporini MA, Barnes AB, Rosay M, Maas WE, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of GNNQQNY Nanocrystals and Amyloid Fibrils. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2010;12(22):5911–5919. doi: 10.1039/c003661g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akbey Ü, Franks WT, Linden A, Lange S, Griffin RG, Rossum B.-J. v., Oschkinat H. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Deuterated Proteins. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2010;49:7803–7806. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linden AH, Lange S, Franks WT, Akbey U, Specker E, Rossum B. J. v., Oschkinat H. Neurotoxin Ii Bound to Acetylcholine Receptors in Native Membranes Studied by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:19266–19269. doi: 10.1021/ja206999c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potapov A, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced 13C NMR Spectroscopy of Static Biological Solids. J Magn Reson. 2013;231(0):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi H, Ayala I, Bardet M, De Paëpe G, Simorre J-P, Hediger S. Solid-State NMR on Bacterial Cells: Selective Cell Wall Signal Enhancement and Resolution Improvement Using Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135(13):5105–5110. doi: 10.1021/ja312501d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gelis I, Vitzthum V, Dhimole N, Caporini M, Schedlbauer A, Carnevale D, Connell S, Fucini P, Bodenhausen G. Solid-State NMR Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization as a Novel Tool for Ribosome Structural Biology. J Biomol NMR. 2013;56(2):85–93. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lesage A, Lelli M, Gajan D, Caporini MA, Vitzthum V, Mieville P, Alauzun J, Roussey A, Thieuleux C, Mehdi A, et al. Surface Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132(44):15459–15461. doi: 10.1021/ja104771z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lelli M, Gajan D, Lesage A, Caporini MA, Vitzthum V, Mieville P, Heroguel F, Rascon F, Roussey A, Thieuleux C, et al. Fast Characterization of Functionalized Silica Materials by Silicon-29 Surface-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy Using Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(7):2104–2107. doi: 10.1021/ja110791d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lafon O, Thankamony ASL, Kobayashi T, Carnevale D, Vitzthum V, Slowing II, Kandel K, Vezin H, Amoureux J-P, Bodenhausen G, et al. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Loaded with Surfactant: Low Temperature Magic Angle Spinning 13C and 29si NMR Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2012;117(3):1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lumata L, Merritt ME, Hashami Z, Ratnakar SJ, Kovacs Z. Production and NMR Characterization of Hyperpolarized 107,109ag Complexes. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2012;51(2):525–527. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michaelis VK, Markhasin E, Daviso E, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Oxygen-17. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2012;3(15):2030–2034. doi: 10.1021/jz300742w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vitzthum V, Mieville P, Carnevale D, Caporini MA, Gajan D, Cope C, Lelli M, Zagdoun A, Rossini AJ, Lesage A, et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Quadrupolar Nuclei Using Cross Polarization from Protons: Surface-Enhanced Aluminium-27 NMR. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1988–1990. doi: 10.1039/c2cc15905h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitzthum V, Caporini MA, Bodenhausen G. Solid-State Nitrogen-14 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Using a Gyrotron. Jour Magn Resonance. 2010:204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michaelis VK, Corzilius B, Smith AA, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of 17o: Direct Polarization. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2013 doi: 10.1021/jp408440z. 10.1021/jp408440z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maly T, Andreas LB, Smith AA, Griffin RG. 2h-DNP-Enhanced 2h-13C Solid-State NMR Correlation Spectroscopy. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2010;12(22):5872–5878. doi: 10.1039/c003705b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanc F, Sperrin L, Jefferson DA, Pawsey S, Rosay M, Grey CP. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enhanced Natural Abundance 17o Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135(8):2975–2978. doi: 10.1021/ja4004377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lafon O, Thankamony ASL, Rosay M, Aussenac F, Lu X, Trebosc J, Bout-Roumazeilles V, Vezin H, Amoureux J-P. Indirect and Direct 29si Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Dispersed Nanoparticles. Chemical Communications. 2013;49(28):2864–2866. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bajaj VS, Hornstein MK, Kreischer KE, Sirigiri JR, Woskov PP, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Herzfeld J, Temkin RJ, Griffin RG. 250 GHz Cw Gyrotron Oscillator for Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in Biological Solid State NMR. J Magn Reson. 2007;189(2):251–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thurber KR, Yau WM, Tycko R. Low-Temperature Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at 9.4 T with a 30 mW Microwave Source. J Magn Reson. 2010;204(2):303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allen PJ, Creuzet F, Degroot HJM, Griffin RG. Apparatus for Low-Temperature Magic-Angle Spinning Nmr. J Magn Reson. 1991;92(3):614–617. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barnes AB, Markhasin E, Daviso E, Michaelis VK, Nanni EA, Jawla SK, Mena EL, DeRocher R, Thakkar A, Woskov PP, et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at 700 MHz/460 GHz. J Magn Reson. 2012;224:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuki Y, Takahashi H, Ueda K, Idehara T, Ogawa I, Toda M, Akutsu H, Fujiwara T. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Experiments at 14.1 T for Solid-State NMR. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2010;12(22):5799–5803. doi: 10.1039/c002268c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barnes AB, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Matsuki Y, Bajaj VS, van der Wel PCA, DeRocher R, Bryant J, Sirigiri JR, Temkin RJ, Lugtenburg J, et al. Cryogenic Sample Exchange NMR Probe for Magic Angle Spinning Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J Magn Reson. 2009;198(2):261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimon D, Hovav Y, Feintuch A, Goldfarb D, Vega S. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in the Solid State: A Transition between the Cross Effect and the Solid Effect. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2012;14(16):5729–5743. doi: 10.1039/c2cp23915a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hovav Y, Levinkron O, Feintuch A, Vega S. Theoretical Aspects of Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in the Solid State: The Influence of High Radical Concentrations on the Solid Effect and Cross Effect Mechanisms. Applied Magnetic Resonance. 2012;43(1–2):21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu KN, Bajaj VS, Rosay M, Griffin RG. High-Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Using Mixtures of Tempo and Trityl Radicals. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2007;126(4) doi: 10.1063/1.2429658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corzilius B, Smith AA, Barnes AB, Luchinat C, Bertini I, Griffin RG. High-Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with High-Spin Transition Metal Ions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(15):5648–5651. doi: 10.1021/ja1109002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corzilius B, Smith AA, Griffin RG. Solid Effect in Magic Angle Spinning Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2012;137(5) doi: 10.1063/1.4738761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith AA, Corzilius B, Barnes AB, Maly T, Griffin RG. Solid Effect Dynamic Nuclear Polarization and Polarization Pathways. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2012;136(1) doi: 10.1063/1.3670019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith AA, Corzilius B, Bryant JA, DeRocher R, Woskov PP, Temkin RJ, Griffin RG. A 140 GHz Pulsed Epr/212 MHz NMR Spectrometer for DNP Studies. J Magn Reson. 2012;223:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu KN, Debelouchina GT, Smith AA, Griffin RG. Quantum Mechanical Theory of Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in Solid Dielectrics. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2011;134(12) doi: 10.1063/1.3564920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hovav Y, Feintuch A, Vega S. Theoretical Aspects of Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in the Solid State - the Cross Effect. J Magn Reson. 2012;214:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu K-N, Song C, Yu H.-h., Swager TM, Griffin RG. High-Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Using Biradicals: A Multifrequency Epr Lineshape Analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:052321. doi: 10.1063/1.2816783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thurber KR, Tycko R. Theory for Cross Effect Dynamic Nuclear Polarization under Magic-Angle Spinning in Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance: The Importance of Level Crossings. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2012;137(8) doi: 10.1063/1.4747449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mentink-Vigier F, Akbey Ü, Hovav Y, Vega S, Oschkinat H, Feintuch A. Fast Passage Dynamic Nuclear Polarization on Rotating Solids. J Magn Reson. 2012;224(0):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gerfen GJ, Becerra LR, Hall DA, Griffin RG, Temkin RJ, Singel DJ. High-Frequency (140 Ghz) Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization - Polarization Transfer to a Solute in Frozen Aqueous-Solution. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1995;102(24):9494–9497. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hall DA, Maus DC, Gerfen GJ, Inati SJ, Becerra LR, Dahlquist FW, Griffin RG. Polarization-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy of Biomolecules in Frozen Solution. Science. 1997;276:930–932. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Corzilius B, Andreas LB, Smith AA, Ni QZ, Griffin RG. Paramagnet Induced Signal Quenching in MAS-DNP Experiments on Homogeneous Solutions. J Magn Reson. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.11.013. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Gajan D, Rascon F, Rosay M, Maas WE, Coperet C, Lesage A, Emsley L. One Hundred Fold Overall Sensitivity Enhancements for Silicon-29 NMR Spectroscopy of Surfaces by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with Cpmg Acquisition. Chemical Science. 2012;3(1):108–115. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lange S, Linden AH, Akbey U, Franks WT, Loening NM, van Rossum BJ, Oschkinat H. The Effect of Biradical Concentration on the Performance of DNP-MAS-NMR. J Magn Reson. 2012;216:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song CS, Hu KN, Joo CG, Swager TM, Griffin RG. TOTAPOL: A Biradical Polarizing Agent for Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Experiments in Aqueous Media. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(35):11385–11390. doi: 10.1021/ja061284b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsuki Y, Maly T, Ouari O, Karoui H, Le Moigne F, Rizzato E, Lyubenova S, Herzfeld J, Prisner T, Tordo P, et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with a Rigid Biradical. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2009;48(27):4996–5000. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kiesewetter MK, Corzilius B, Smith AA, Griffin RG, Swager TM. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with a Water-Soluble Rigid Biradical. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134(10):4537–4540. doi: 10.1021/ja212054e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zagdoun A, Casano G, Ouari O, Lapadula G, Rossini AJ, Lelli M, Baffert M, Gajan D, Veyre L, Maas WE, et al. A Slowly Relaxing Rigid Biradical for Efficient Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Surface-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy: Expeditious Characterization of Functional Group Manipulation in Hybrid Materials. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134(4):2284–2291. doi: 10.1021/ja210177v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zagdoun A, Casano G, Ouari O, Schwarzwälder M, Rossini AJ, Aussenac F, Yulikov M, Jeschke G, Copéret C, Lesage A, et al. Large Molecular Weight Nitroxide Biradicals Providing Efficient Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at Temperatures up to 200 K. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja405813t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sauvée C, Rosay M, Casano G, Aussenac F, Weber RT, Ouari O, Tordo P. Highly Efficient, Water-Soluble Polarizing Agents for Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at High Frequency. Angewandte Chemie. 2013;125(41):11058–11061. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borka L. Polymorphism of Indomethacin - New Modifications, Their Melting Behavior and Solubility. Acta Pharmaceutica Suecica. 1974;11(3):295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imaizumi H, Nambu N, Nagai T. Pharmaceutical Interaction in Dosage Forms and Processing .18. Stability and Several Physical-Properties of Amorphous and Crystalline Forms of Indomethacin. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1980;28(9):2565–2569. doi: 10.1248/cpb.28.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ong TC, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Walish JJ, Michaelis VK, Corzilius B, Smith AA, Clausen AM, Cheetham JC, Swager TM, Griffin RG. Solvent-Free Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Amorphous and Crystalline Ortho-Terphenyl. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2013;117(10):3040–3046. doi: 10.1021/jp311237d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Frantz DK, Walish JJ, Swager TM. Organic Letters. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haze O, Corzilius B, Smith AA, Griffin RG, Swager TM. Water-Soluble Narrow-Line Radicals for Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14287–14290. doi: 10.1021/ja304918g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Michaelis VK, Smith AA, Corzilius B, Haze O, Swager TM, Griffin RG. High-Field 13C DNP with a Radical Mixture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja312265x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lafon O, Rosay M, Aussenac F, Lu X, Trebosc J, Cristini O, Kinowski C, Touati N, Vezin H, Amoureux J-P. Beyond the Silica Surface by Direct Silicon-29 Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Angewandte Chemie. 2011;50(36):8367–8370. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maly T, Miller A-F, Griffin RG. In-Situ High-Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization – Direct and Indirect Polarization of 13C Nuclei. Chemphyschem. 2010;11:999–1001. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Macholl S, Johannesson H. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with Trityls at 1.2 K. Applied Magnetic Resonance. 2008;34(3–4):509–522. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thaning M. Free Radicals. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Farrar CT, Hall DA, Gerfen GJ, Rosay M, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Griffin RG. High-Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in the Nuclear Rotating Frame. J Magn Reson. 2000;144(1):134–141. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Michaelis VK, Markhasin E, Daviso E, Corzilius B, Smith A, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. DNP NMR of Oxygen-17 Using Mono- and Bi-Radical Polarizing Agents. Experimental NMR Conference; Miami, FL, Miami, FL. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barnes AB, Corzilius B, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Andreas LB, Bajaj VS, Matsuki Y, Belenky ML, Lugtenburg J, Sirigiri JR, Temkin RJ, et al. Resolution and Polarization Distribution in Cryogenic DNP/MAS Experiments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12 doi: 10.1039/c003763j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Andreas LB, Barnes AB, Corzilius B, Chou JJ, Miller EA, Caporini M, Rosay M, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Study of Inhibitor Binding to the M2 Proton Transporter from Influenza A. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2774–2782. doi: 10.1021/bi400150x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bayro MJ, Debelouchina GT, Eddy MT, Birkett NR, MacPhee CE, Rosay M, Maas WE, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. Intermolecular Structure Determination of Amyloid Fibrils with Magic-Angle Spinning, Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13967–13974. doi: 10.1021/ja203756x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bayro MJ, Maly T, Birkett N, MacPhee C, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. High-Resolution MAS NMR Analysis of Pi3-Sh3 Amyloid Fibrils: Backbone Conformation and Implications for Protofilament Assembly and Structure. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7474–7488. doi: 10.1021/bi100864t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Debelouchina GT, Platt GW, Bayro MJ, Radford SE, Griffin RG. Intermolecular Alignment in B2-Microglobulin Amyloid Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17077–17079. doi: 10.1021/ja107987f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van der Wel PCA, Hu KN, Lewandowski J, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Amyloidogenic Peptide Nanocrystals: GNNQQNY, a Core Segment of the Yeast Prion Protein Sup35p. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(33):10840–10846. doi: 10.1021/ja0626685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Hegner F, Schwarzwälder M, Gajan D, Copéret C, Lesage A, Emsley L. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR Spectroscopy of Microcrystalline Solids. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16899–16908. doi: 10.1021/ja308135r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ravera E, Corzilius B, Michaelis VK, Rosa C, Griffin RG, Luchinat C, Bertini I. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Sedimented Solutes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja312553b. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ravera E, Corzilius B, Michaelis VK, Luchinat C, Griffin RG, Bertini I. DNP-Enhanced MAS NMR of Bovine Serum Albumin Sediments and Solutions. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2013 doi: 10.1021/jp500016f. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takahashi H, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Matrix-Free Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enables Solid-State NMR 13C-13C Correlation Spectroscopy of Proteins at Natural Isotopic Abundance. Chemical Communications. 2013 doi: 10.1039/c3cc45195j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fragai M, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E. Practical Considerations over Spectral Quality in Solid State NMR Spectroscopy of Soluble Proteins. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2013;57(2):155–166. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E. Water and Protein Dynamics in Sedimented Systems: A Relaxometric Investigation. Chemphyschem. 2013;14(13):3156–3161. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bertini I, Engelke F, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E, Rosa C, Turano P. NMR Properties of Sedimented Solutes. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2012;14(2):439–447. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22978h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gardiennet C, tz AKS, Hunkeler A, Kunert B, Terradot L, Bçckmann A, Meier BH. A Sedimented Sample of a 59 kDa Dodecameric Helicase Yields High-Resolution Solid-State NMR Spectra. Angew. Chem. Int. 2012;51(31):7855–7858. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gelis I, Vitzthum V, Dhimole N, Caporini MA, Schedlbauer A, Carnevale D, Connell SR, Fucini P, Bodenhausen G. Solid-State NMR Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization as a Novel Tool for Ribosome Structural Biology. J Biomol NMR. 2013;56:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E. Sednmr: On the Edge between Solution and Solid-State NMR. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2013;46(9):2059–2069. doi: 10.1021/ar300342f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E, Reif B, Turano P. Solid-State NMR of Proteins Sedimented by Ultracentrifugation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(26):10396–10399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bajaj VS, Wel P. C. A. v. d., Griffin RG. Observation of a Low-Temperature, Dynamically Driven Structural Transition in a Polypeptide by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Jour. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:118–128. doi: 10.1021/ja8045926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Debelouchina GT, Bayro MJ, Wel P. C. A. v. d., Caporini MA, Barnes AB, Rosay M, Maas WE, Griffin RG. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of GNNQQNY Nanocrystals and Amyloid Fibrils. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12 doi: 10.1039/c003661g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pike KJ, Kemp TF, Takahashi H, Day R, Howes AP, Kryukov EV, MacDonald JF, Collis AE, Bolton DR, Wylde RJ, et al. A Spectrometer Designed for 6.7 and 14.1 T DNP-Enhanced Solid-State MAS NMR Using Quasi-Optical Microwave Transmission. J Magn Reson. 2012;215:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Torrezan AC, Han S-T, Mastovsky I, Shapiro MA, Sirigiri JR, Temkin RJ, Barnes AB, Griffin RG. Continuous-Wave Operation of a Frequency Tunable 460 GHz Second-Harmonic Gyrotron for Enhanced Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 2010;38:1150–1159. doi: 10.1109/TPS.2010.2046617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Theil EC. Ferritin - Structure, Gene-Regulation, and Cellular Function in Animals, Plants and Microorganisms. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1987;56:289–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lalli D, Turano P. Solution and Solid State NMR Approaches to Draw Iron Pathways in the Ferritin Nanocage. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ar4000983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Matzapetakis M, Turano P, Theil E, Bertini I. 13C-13C Noesy Spectra of a 480 kda Protein: Solution NMR of Ferritin. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2007;38(3):237–242. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Turano P, Lalli D, Felli IC, Theil EC, Bertini I. NMR Reveals Pathway for Ferric Mineral Precursors to the Central Cavity of Ferritin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(2):545–550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908082106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Harrison PM, Mainwaring WI, Hofmann T. Structure of Apoferritin - Amino Acid Composition and End-Groups. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1962;4(3):251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]