Abstract

Background

Weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is common. Endoscopic sclerotherapy is increasingly used for treatment of this weight regain.

Objectives

To report safety, outcomes, durability, and predictors of response to sclerotherapy from a large prospective cohort.

Design

Retrospective analysis of prospective cohort study of patients with weight regain after RYGB.

Patients

231 consecutive patients undergoing 575 sclerotherapy procedures between September 2008 – March 2011.

Interventions

Single or multiple sclerotherapy procedures to inject sodium morrhuate into the rim of the gastrojejunal anastomosis.

Main outcome measurements

We report weight loss, complications, and predictors of response. We also used Kaplan-Meir survival analysis and log-rank test to compare time to continuation of weight regain after sclerotherapy between patients undergoing a single vs. multiple sclerotherapy procedures.

Results

At 6 and 12 months from last sclerotherapy procedure weight regain stabilized in 92% and 78% of the cohort, respectively. Those who underwent 2 or 3 sclerotherapy sessions had significantly higher rates of weight regain stabilization than those who underwent a single session (90% vs. 60% at 12 months) (p= 0.003). The average weight loss at 6 months from last sclerotherapy session for the entire cohort was (10 lb, SD 16) representing 18% of the weight regained after RYGB. A subset of 73 patients (32% of the cohort) had higher weight loss at 6 months (26 lb, SD 12) representing 61% of the weight regained. Predictors of favorable outcome included higher magnitude of weight regain and number of sclerotherapy procedures. Bleeding was reported in 2.4% of procedures and transient diastolic blood pressure elevations in 15%, without adverse health outcomes. No gastrointestinal perforations were reported.

Conclusions

Endoscopic sclerotherapy appears to be a safe and effective tool for the management of weight regain after RYGB.

Keywords: Sclerotherapy, gastric bypass, RYGB, weight regain, recidivism, anastomosis, endoscopic, endoscopic suturing, endoscopic therapy, obesity

Introduction

Obesity and its associated conditions, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, have reached epidemic proportions. The burden of this disease is particularly evident in the developed world, where the consequences include substantially increased morbidity, mortality, and cost to the health care system[1–3] Of the many therapeutic approaches for the treatment of obesity and its complications, gastrointestinal weight loss surgery (GIWLS) shows the most promise in achieving significant and sustained weight loss and diabetes resolution, when compared with medications or dietary and behavioral modifications. [4]

The proven efficacy of GIWLS coupled with an improved surgical safety profile afforded by the introduction of laparoscopic techniques have led to a surge in the number of bariatric procedures performed in the USA and worldwide, with an estimated 220,000 bariatric operations performed in the USA and Canada in 2008. [5–6] Despite this increase, a large mismatch exists between the magnitude of the obesity epidemic and the number of GIWLS performed, promising further increase in the number of bariatric surgery procedures.

Even after a common and effective procedure such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB), weight regain in the long-term is typical and associated with negative impact on patient quality of life and health status. [7–8] This coupled with a prohibitive rate of morbidity and mortality associated with surgical revision [9–11], have presented the field of interventional endoscopy with the challenge of preventing and treating this unfavorable post-RYGB outcome.

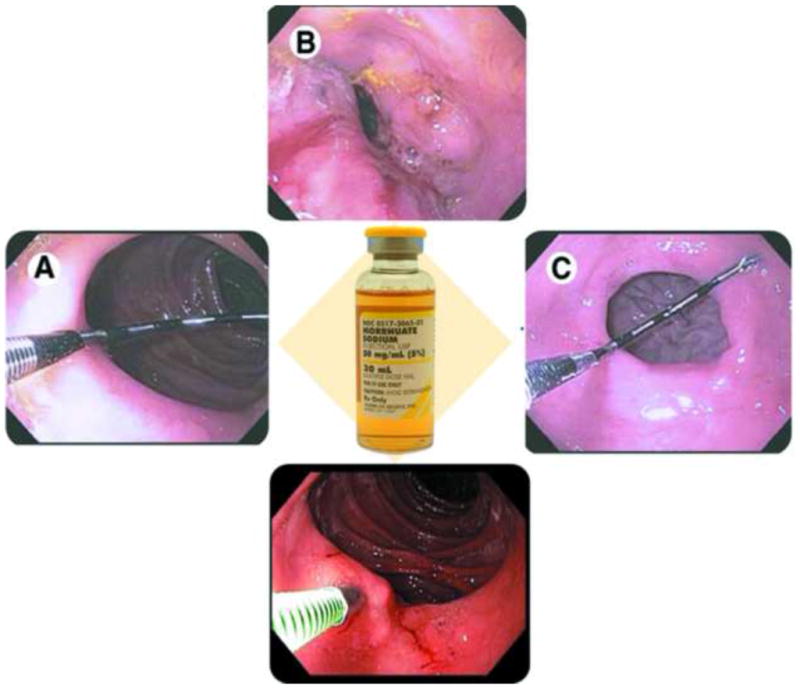

Much of the focus on endoscopic revision of the RYGB has been on the gastrojejunal anastomosis and gastric pouch, as dilation of the anastomosis, and/or enlargement of the gastric pouch, are thought to be risk factors for suboptimal weight loss and weight regain after surgery [12–13]. Although postsurgical physiology and the exact mechanisms of weight regain remain unclear, this has led to the development of a variety of less invasive endoscopic techniques that focus on the reduction of gastrojejunal stomal aperture and gastric pouch volume. [14] Of these, endoscopic sclerotherapy (Figure 1) has started to gain acceptance for a variety of reasons, including wide spread availability, ease of administration, short procedural time, relatively low cost, and short-term effectiveness demonstrated in small uncontrolled studies. [15–19]

Figure 1.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy for weight regain after RYGB. A) Endoscopic measurement of the GJ stoma diameter. B) Injection of sodium morrhuate into the rim of the GJ stoma and the appearance of the GJ stoma immediately after the injections. C) The GJ stoma 3 months after sclerotherapy.

In this study we report short and mid-term outcomes, complications, and predictors of response to sclerotherapy as a treatment for weight regain after RYGB, in a consecutive cohort of 231 subjects undergoing 575 procedures. We also compare outcomes after single vs. multiple sclerotherapy sessions to demonstrate a dose response effect.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on 231 consecutive patients undergoing 575 sclerotherapy sessions for weight regain after RYGB between September 2008 – March 2011. All patients had reached nadir weight after RYGB, and were actively gaining weight at the time of inclusion to the study. Weight regain was defined from nadir, and subjects with gastrogastric fistula on baseline upper endoscopy or barium study were excluded. All patients had failed dietary counseling and conservative measures within a weight management program. Patients were also seen in clinic before their first sclerotherapy session to discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives to this procedure. The available literature and our limited experience with the procedure were discussed with patients at this visit.

Our primary outcome was time to continuation of weight regain after last scleratherapy procedure. Continuation of weight regain was defined as equal to or greater than 5 pounds (lbs) increase from pre-sclerotherapy weight. Our secondary outcome was absolute weight change in pounds at an average follow-up of 6 months from last sclerotherapy procedure.

All subjects were interviewed before each sclerotherapy procedure to gather base-line demographics, weight trends after RYGB, and information about potential confounders. This information was recorded on standardized data entry forms. Subjects’ heights and weights were measured before each sclerotherapy procedure and their weight changes from last sclerotherapy procedure were recorded at each follow-up endoscopy and clinic appointment. Gastric pouch length and GJ stoma diameter were measured before sclerotherapy using a consistent protocol. Calibrations on the upper endoscope shaft were used to measure gastric pouch length, and a direct reading calibrated endoscopic measuring instrument (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) was positioned across the GJ stoma to measure maximal diameter (figure 1).

Sclerotherapy was performed by injecting sodium morrhuate (50mg/mL) (Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Shirley, NY) into the rim of the GJ anastomosis using an endoscopic sclerotherapy needle. A 2-cc test dose was first administered, followed by a wait of 3 minutes to assess for sensitivity and acute adverse reactions. After the test dose, 2-cc aliquots were injected circumferentially surrounding the GJ anastomosis. The total volume of sodium morrhuate injected per session was dependant on GJ stoma diameter and tissue response to injections. Although the GJ stoma diameter was significantly reduced immediately after sclerotherapy injections, this only represents transient narrowing from inflammation and edema (Figure 1). The majority of cases were performed under conscious sedation. All patients received intravenous antibiotics, typically ciprofloxacin, and 50 mg of diphenhydramine before the procedure. All patients were also discharged on a 3 day course of either ciprofloxacin or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim in liquid form. Restriction from oral intake was required for 24 hours after the procedure and the diet was then advanced to regular over a period of 4 weeks. Oral medications were converted to liquid formulation when possible for the duration of solids restriction.

Statistical analysis

We used Kaplan-Meir survival analysis and log-rank test to compare time to continuation of weight regain after sclerotherapy. Linear regression was sued to identify significant clinical and endoscopic predictors of response to sclerotherapy. Two-sided paired t-test were used to compare weight before and after sclerotherapy. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P-value of .05 or less. A fixed effects meta-analysis was used to pool data from published sclerotherapy series for comparison. Statistical modeling was performed using SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Biostat, Englewood, NJ) was used for data pooling. Graphing was performed using JMP software (version 8; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

I- Baseline cohort and procedural characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline cohort and procedural characteristics for the enter cohort, and compare some of these characteristics in subjects undergoing one vs. two/three sclerotherapy sessions. The average age of the cohort was 47, 90% were female, 72% Whites, 16% Blacks, and 12% Hispanics. The median weight regain from nadir weight lost was 36% [IQR 22 – 50], and the average baseline GJ stoma diameter was 19 mm (SD 6). The majority of procedures were performed under conscious sedation with standard upper endoscopy sedation doses as shown in table 1b. The median number of sclerotherapy procedures performed per patient was 2 with 16 ml (SD 5) average volume of sodium morrhuate injected per procedure.

Table 1.

| Table 1a. Baseline cohort characteristics | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 47 (10) |

|

| |

| Gender (% female) | 90% |

|

| |

| Race (%) | |

| • White | 72% |

| • Black | 16% |

| • Hispanic | 12% |

|

| |

| Type of RYGB (%) | |

| • Open | 51% |

| • Laproscopic | 45% |

| • Revision | 4% |

|

| |

| RYGB center (%) | |

| • Brigham and Women’s Hospital | 63% |

| • Other | 37% |

|

| |

| Complications after RYGB (%) | |

| • Erosions / ulcers | 9.5% |

| • Revised gastrogastric fistulas | 3% |

| • Adhesions / small bowel obstruction | 3% |

| • Stricture formation | 1% |

|

| |

| Pre RYGB BMI (mean, SD) | 50 (8.9) |

|

| |

| Weight lost after RYGB (%) (median, IQR) | 39% [33 – 45] |

|

| |

| Weight regain from nadir (%) (median, IQR) | 36% [22 – 50] |

|

| |

| Time between RYGB and first scleratherapy session (years)(mean, SD) | 5.7 (2.5) |

|

| |

| Number of sclerotherapy sessions (%) | |

| • 1 | 35% |

| • 2 | 38% |

| • 3 | 20% |

| • 4 | 7% |

|

| |

| Baseline gastrojejunal stoma diameter (mm) (mean, SD) | 19 (6) |

|

| |

| Previous endoscopic suturing repair (%) | 22% |

| Table 1b. Baseline procedure characteristics

| |

|---|---|

| Number of sessions (median, IQR) | 2 [1 – 3] |

|

| |

| Volume of sodium morrhuate per session (ml) (mean, SD) | 16 (5) |

|

| |

| Sedation dose (mean, SD) | |

| • Midazolam (mg) | 5 (2) |

| • Fentanyl (mg) | 140 (45) |

| • Diphenhydramine (mg) | 50 |

| Table 1c. Baseline characteristics of subjects undergoing one compared to two/three sclerotherapy sessions | ||

|---|---|---|

| One N = 80 |

Two / Three N = 134 |

|

| Age (Year, SD) | 48 (10) | 46 (9) |

| Year RYGB (SD) | 2003 (3) | 2003 (3) |

| Pre-RYGB BMI (SD) | 50 (10) | 50 (8) |

| Weight lost after RYGB (%)(SD) | 38 (8) | 39 (9) |

| Weight regain after RYGB (%)(SD) | 40 (22) | 37.4 (19) |

| Baseline GJ stoma diameter (mm) (SD) | 19 (6) | 19 (5.5) |

| Volume of sodium morrhuate per session (ml) (mean, SD) | 17 (5.6) | 16 (5.5) |

| Drop-out number (%) | 9 (11%) | 10 (8%) |

Table 1c shows a similar distribution of age, year of RYGB, pre-RYGB BMI, percent weight lost after RYGB, percent weight regain from nadir, and baseline GJ stoma diameter between patients who underwent one sclerotherapy session vs. two/ three.

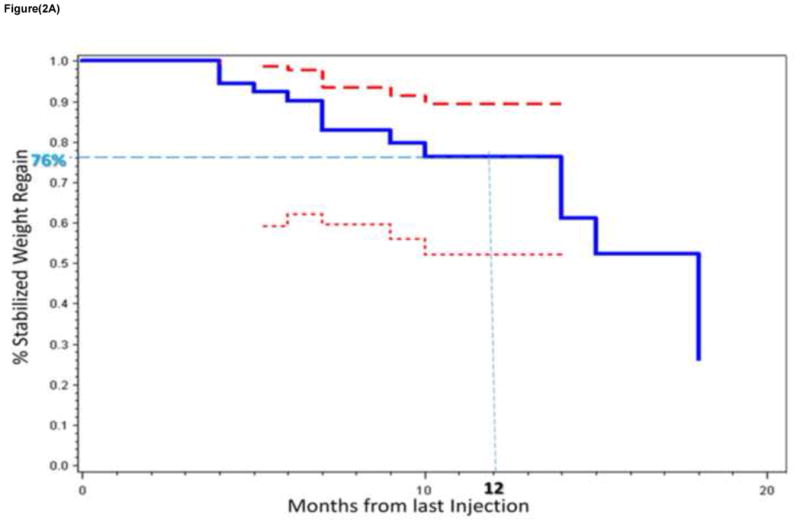

II- Weight regain stabilizes after endoscopic sclerotherapy

Figure 2 shows the percent of the cohort stabilizing their weight regain in the months after the last sclerotherapy procedure. Weight regain stabilization was defined as either weight decrease or gain of less than 5 lbs from the pre-sclerotherapy weight. As seen in figure 2a, 76% of the cohort stabilized their weight regain at 12 months from the last sclerotherapy procedure. A significantly higher percentage of those who underwent 2 or 3 sclerotherapy procedures stabilized their weight regain after RYGB compared to those who underwent only one sclerotherapy procedure, 90% vs 58% respectively at 12 months from the last sclerotherapy procedure (p = 0.0032). This difference continued to be significant after stratifying by previous endoscopic suturing repair of the gastric pouch and/or GJ stoma (p = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Kaplan-Meir plot of the percent of the cohort stabilizing their weight regain after RYGB in the months after the last sclerotherapy session (solid blue line). The 95th percent confidence bands (CB) are also shown (upper CB represented by a thick red dashed line and lower CB by a thin red dashed line).

Figure 2b. Two Kaplan-Meir plots of the percent stabilization of weight regain in those who received one sclerotherapy session (red solid line) vs. 2 or 3 session (blue dashed line).

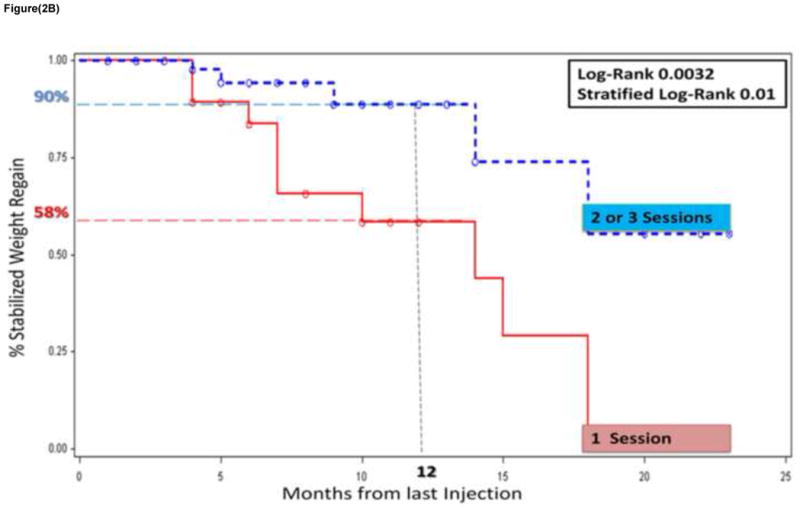

III- Distribution of weight loss at 6 months

Figure 3 shows a normal distribution of weight loss at an average follow-up of 6 months form the last sclerotherapy session for the entire cohort. The mean weight loss was 10 lbs (SD 16) representing 18% of the weight regained from nadir post RYGB weight, and 4.4% of the total body weight at the time of the first sclerotherapy session. This was significantly different from the pre-sclerotherapy weight (p < 0.005). A third of the cohort (73 patients) were high responders with a mean weight loss at 6 months of 26 lbs (SD 12), representing 61% of the weight regained (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Normal distribution of weight loss in the entire cohort at an average follow-up of 6 months from last sclerotherapy procedure. Area highlighted in light pink indicates percent high responders.

IV- Predictors of response to sclerotherapy

Given the distribution of response to sclerotherapy for treatment of weight regain, we used multivariate linear regression analysis to identify significant predictors of response to this procedure as a treatment modality for weight regain after RYGB. As seen in table 2, the greater the amount of weight regain from nadir and the more sclerotherapy sessions performed predicted better response. Patients who had prior endoscopic suturing repair of the gastric pouch and/or GJ stoma had a trend to better response after sclerotherapy (p = 0.056). The diameter of the GJ stoma prior sclerotherapy was not associated with response (p = 0.52).

Table 2.

Multivariate linear regression of predictors of response to sclerotherapy

| Standardized Beta | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.68 |

|

| ||

| Race | 0.03 | 0.64 |

| Non-white vs. White | ||

|

| ||

| Follow-up time from last injection (months) | −0.10 | 0.1 |

|

| ||

| Weight regain from nadir (%) | 0.33 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Previous endoscopic suturing repair | 0.12 | 0.056 |

|

| ||

| GJ stoma diameter (mm) | −0.04 | 0.52 |

|

| ||

| Number of sclerotherapy sessions | ||

| 1 | 0.21 | 0.002 |

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

V- Sclerotherapy related complications

Table 3 details the intra and post-procedural complications of sclerotherapy for treatment of weight regain after RYGB. Three patients were admitted for work up of post-procedural abdominal pain and were managed conservatively. Small ulcerations were found on repeat endoscopy after 6 procedures (1%). Bleeding occurred in 14 out of 575 (2.4%) sclerotherapy procedures, with 8 requiring endoscopic clipping. No gastrointestinal perforations occurred in the cohort. Transient diastolic blood pressure elevations were observed in 15% of the procedures and correlated with higher volumes of sodium morrhuate (odds ratio 1.7, CI 0.9 – 3.1). Thse transient diastolic blood pressure elevations resolved by the time patients were in recovery and were not associated with any adverse health outcomes.

Table 3.

Intra and post-procedural complications related to sclerotherapy after 575 procedures

|

Intra-procedural

| |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 0 |

|

| |

| Hypersensitivity reaction to sodium morrhuate | 0 |

|

| |

| Bleeding | 14 (2.4%) |

| • Stopped spontaneously | 4 |

| • Epinephrine injection | 2 |

| • Epinephrine and endoscopic clipping | 8 |

|

| |

| Transient diastolic blood pressure elevation | |

| • > 105 mmHg | 64 / 425 (15%) |

| • > 25 mmHg from pre-procedure reading | |

|

| |

|

Post-procedural

| |

| Delayed bleeding | 1 (0.2%) |

|

| |

| Admissions for post-procedural abdominal pain | 3 (0.5%) |

|

| |

| Small ulcers on repeat upper endoscopy | 6 (1%) |

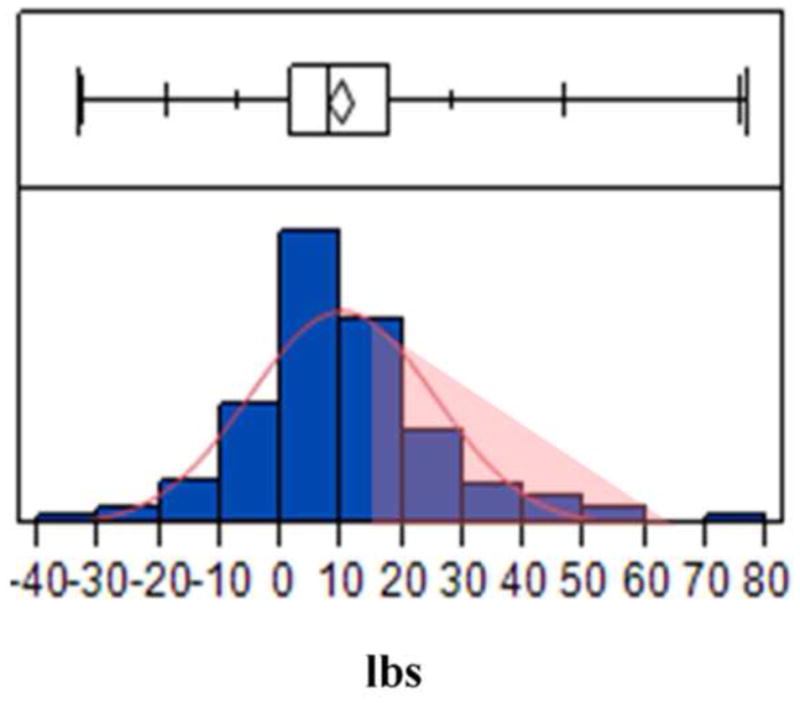

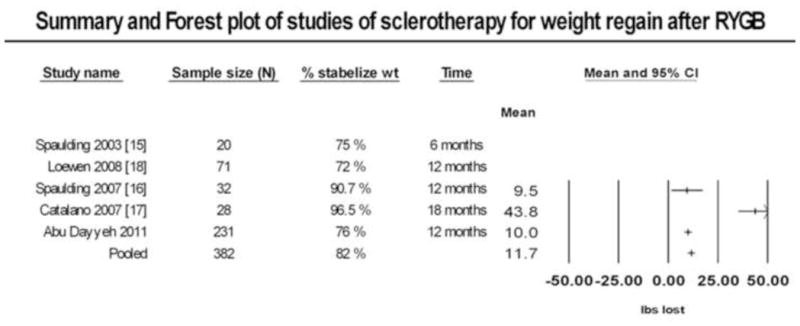

VI- Data pooling from published sclerotherapy series

Figure 4 shows a summary of published studies using sclerotherapy for weight regain after RYGB. There are a total of 151 patient in published series, with an average follow-up of 12 months. All studies reported the percent of subject stabilizing their weight regain after sclerotherapy, defined as weight loss or no further weight regain on clinical follow-up. The average percent of subjects stabilizing their weight regain after sclerotherapy across all studies was 83.5% compared to 76% at 12 months in our cohort. Three studies reported actual mean weight loss in their entire respective cohorts. These were pooled using a fixed effects meta-analysis showing a mean weight loss of 11.7 lbs (95th CI 9.7 – 13.6) at an average follow-up of 12 months from last sclerotherapy procedure.

Figure 4.

Summary and Forest plot showing individual and pooled results from studies of sclerotherapy for treatment of weight regain after RYGB. Percent stabilization in weight regain was available in all studies. Actual weight loss for the entire cohort was available for three studies.

Discussion

Given the projected increase in the number of RYGB surgeries, fueled by the large mismatch between disease burden and those receiving effective treatment, a number of endoscopic device and techniques have been introduced to manage the weight regain commonly observed after bariatric surgery. [14]

In order to satisfy patients, providers, and payers, such endoscopic approaches must be effective, minimally invasive, safe, durable, and cost-effective. In this report, we demonstrated in a large prospective cohort the minimally invasive nature, safety, and mid-term durability of sclerotherapy as a treatment modality for weight regain after RYGB. Furthermore, we demonstrated a dose-response effect of sclerotherapy in multivariate linear regression analysis and significant superiority of multiple sclerotherapy procedure compared to a single procedure on Kaplan-Meir analysis (Figure 2b). Thus, arguing for superiority over an active control group undergoing a less invasive alternative.

Our results were consistent with others showing stabilization of weight regain in the majority of post RYGB patients undergoing sclerotherapy (Figure 4). The degree of weight loss among these studies; however, was modest with the exception to the study by Catalano and colleagues, which differed in selecting patients with higher weight regain and more aggressive sclerotherapy injections as evidenced by higher rates of ulcer formation on repeat endoscopy (36%). [17] These results argue that implementing sclerotherapy protocols as a preventative measure or early in the weight regain trajectory may maximize benefit and minimize risk associated with significant weight regain and the need for more aggressive interventions.

Interestingly, the diameter of the GJ stoma before sclerotherapy was not predictive of treatment response, and sclerotherapy complimented previous endoscopic suturing repair techniques for weight regain after RYGB (Table 2). This underscores the complexity and multifactoerial nature of weight regain, which likely involves an interplay between a permissive psychosocial environment, nutritional habits, and a complex genetic and anatomic milieu that effect many physiological regulatory pathways controlling food-intake behavior and energy. [20–21] Thus, GJ stoma diameter might be a mere surrogate to a compliant gastric pouch outlet, which permits accommodation of larger meal boluses before the activation of gastric wall mechanoreceptors inhibiting orexigenic gastric peptides, such as ghrelin or it could play a more direct role by altering the rate by which the gastric pouch empties partially digested nutrients to the jejunum. [22–27] This, in turn, modulates the production of incretins and other neurohormonal signaling to the brain and other organs altering gastrointestinal motility, satiety and food intake behaviors, insulin secretion, and energy expenditure.[27]

In this study we demonstrated a favorable safety profile of sclerotherapy for the treatment of weight regain after RYGB in a large cohort. However, clinicians should be vigilant and discuss with their patients the potential risks of sodium morrhuate including hypersensitivity reaction, ulcer formation, and bleeding. A complication that deserves discussion given it’s relatively high frequency is that of transient self-limited diastolic blood pressure elevation, observed in 15% of procedures (Table 3). Despite lack of association with adverse health outcomes or events, we caution the use of sclerotherapy in patients with cardiovascular co-morbidities or coagulopathy. Interestingly, older studies on variceal sclerotherapy reported transient hemodynamic changes due to increase in pulmonary and systemic vascular resistance possible mediated by prostaglandins. [28–30]

Several limitations deserve comment. First, although we used patients who received a single sclerotherapy procedure as a reference group these were not randomly selected. Second, the number of sclerotherapy sessions performed and volume of sodium morrhuate used per session was based on endoscopist judgment not on a pre-specified blinded criteria. Third, despite using Kaplan-Meir analysis to account for missing follow-up data, the possibility of informed censoring cannot be excluded in such an observational study not using intention to treat analysis. Finally, we lacked complete information regarding adherence to post-procedural diet and physical activity.

In summary, this is the largest prospective cohort study demonstrating the safety, mid-term durability, and efficacy of sclerotherapy as a treatment modality for weight regain after RYGB. Additionally, it appears that better outcomes are achieved when more than one sclerotherapy session is performed. Longer term safety and weight loss outcomes are also being assessed.

Acknowledgments

This study was reviewed and approved by the Partner’s Institutional Review Board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The Institutional Review Board protocol number is 2003P001597. This study was exempt from written informed consent requirement.

Funding: This project was supported in part by a T32 National Institutes ofHealth training grant to the Massachusetts General Hospital and BarhamAbu Dayyeh (T32DK007191).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, Hinojosa MW, Lane JS. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:928–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery Worldwide 2008. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1605–11. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohn GP, Galanko JA, Overby DW, Farrell TM. Recent trends in bariatric surgery case volume in the United States. Surgery. 2009;146:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christou NV, Look D, Maclean LD. Weight gain after short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Ann Surg. 2006;244:734–40. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikramuddin S, Kellogg TA, Leslie DB. Laparoscopic conversion of vertical banded gastroplasty to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1927–30. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweeney JF, Goode SE, Rosemurgy AS. Redo Gastric Restriction: A Higher Risk Procedure. Obes Surg. 1994;4:244–7. doi: 10.1381/096089294765558458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inabnet WB, 3rd, Belle SH, Bessler M, Courcoulas A, Dellinger P, Garcia L, et al. Comparison of 30-day outcomes after non-LapBand primary and revisional bariatric surgical procedures from the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abu Dayyeh BK, Lautz DB, Thompson CC. Gastrojejunal stoma diameter predicts weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mali J, Jr, Fernandes FA, Valezi AC, Matsuo T, de Menezes MA. Influence of the actual diameter of the gastric pouch outlet in weight loss after silicon ring Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: an endoscopic study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1231–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryou M, Ryan MB, Thompson CC. Current status of endoluminal bariatric procedures for primary and revision indications. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:315–33. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spaulding L. Treatment of dilated gastrojejunostomy with sclerotherapy. Obes Surg. 2003;13:254–7. doi: 10.1381/096089203764467162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaulding L, Osler T, Patlak J. Long-term results of sclerotherapy for dilated gastrojejunostomy after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:623–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalano MF, Rudic G, Anderson AJ, Chua TY. Weight gain after bariatric surgery as a result of a large gastric stoma: endotherapy with sodium morrhuate may prevent the need for surgical revision. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewen M, Barba C. Endoscopic sclerotherapy for dilated gastrojejunostomy of failed gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:539–42. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.09.014. discussion 42–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madan AK, Martinez JM, Khan KA, Tichansky DS. Endoscopic sclerotherapy for dilated gastrojejunostomy after gastric bypass. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:235–7. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vetter ML, Cardillo S, Rickels MR, Iqbal N. Narrative review: effect of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:94–103. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stylopoulos N, Hoppin AG, Kaplan LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass enhances energy expenditure and extends lifespan in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1839–47. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogiso K, Asakawa A, Amitani H, Inui A. Ghrelin: a gut hormonal basis of motility regulation and functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 (Suppl 3):67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfluger PT, Castaneda TR, Heppner KM, Strassburg S, Kruthaupt T, Chaudhary N, et al. Ghrelin, peptide YY and their hypothalamic targets differentially regulate spontaneous physical activity. Physiol Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang PY, Caspi L, Lam CK, Chari M, Li X, Light PE, et al. Upper intestinal lipids trigger a gut-brain-liver axis to regulate glucose production. Nature. 2008;452:1012–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansotia T, Maida A, Flock G, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, Seino Y, et al. Extrapancreatic incretin receptors modulate glucose homeostasis, body weight, and energy expenditure. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:143–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI25483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond B, Fairman RP, Monroe P, Glauser FL, Sugarman H, Davis D. The pulmonary hypertension of sclerosing agents is prevented by cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Am J Med Sci. 1985;290:98–101. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monroe P, Morrow CF, Jr, Millen JE, Fairman RP, Glauser FL. Acute respiratory failure after sodium morrhuate esophageal sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:693–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey-Newton RS, Connors AF, Jr, Bacon BR. Effect of endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy on gas exchange and hemodynamics in humans. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:368–73. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]