Abstract

Objective

The treatment of breast cancer tends to result in physical side effects (e.g., vaginal dryness, stomatitis, and atrophy) that can cause sexual problems. Although studies of early-stage breast cancer have demonstrated that sexual problems are associated with increased depressive symptoms for both patients and their partners, comparatively little is known about these associations in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) and how patients and partners cope together with sexual problems. We examined the links between sexual problems, depressive symptoms, and two types of spousal communication patterns [mutual constructive (MC) and demand-withdraw (DW)] in 191 couples in which the patient was initiating treatment for MBC.

Methods

Patients and partners separately completed paper-pencil surveys.

Results

Multilevel models indicated that high levels of sexual problems were significantly associated with more depressive symptoms only for patients who reported low levels of MC communication (p<0.01) and high levels of DW communication (p<0.0001). In contrast, for partners, greater sexual problems were associated with more depressive symptoms regardless of the type of communication pattern reported. These associations remained significant when we controlled for patients’ reports of average pain and functional and physical well-being and couples’ dyadic adjustment.

Conclusions

Sexual problems were associated with depressive symptoms for both MBC patients and their partners. The way in which patients and partners talk to one another about cancer-related problems appears to influence this association for patients. MBC patients may benefit from programs that teach couples how to minimize DW communication and instead openly and constructively discuss sexual issues and concerns.

Keywords: metastatic breast cancer, sexual problems, depression, communication patterns, couples

Introduction

The treatment of breast cancer can profoundly decrease the patient’s sexual functioning and thus overall quality of life (QOL) [1]. Researchers have largely focused on understanding how different treatment modalities (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy) are associated with physiological indices of sexual functioning (e.g., vaginal atrophy or lubrication). Although such research is important as it is associated with QOL, the focus on physiological indicators of function may neglect important subjective sexual experiences. In addition, the vast majority of studies has excluded patients’ spouses or intimate partners and has failed to examine the effects of sexual problems on couples’ relationships and interaction patterns [2–5]. Finally, very few studies on the sexual consequences associated with cancer have included patients with advanced disease [6, 7]. These shortcomings are unfortunate because sexual relations may help couples maintain closeness and connection during this extremely stressful time and cope with emotional distress [1, 8]. Given these gaps in the literature, we examined the presence of and associations with sexual problems in couples coping with metastatic breast cancer (MBC).

Patients with MBC are a growing segment of the cancer survivor population. A multitude of treatment options such as targeted therapies [9] have allowed many patients to live for years with their disease [10]. Despite such advances, patients with MBC must cope with a host of physical symptoms such as pain [11], sleep disturbances [12], and fatigue [13]. Additionally, 30–100% of women undergoing chemotherapy [1, 14] experience adverse treatment effects that resemble intensified menopausal symptoms (e.g., reduced libido, vaginal dryness, atrophy, and irritation) that can affect sexual function and satisfaction [15]. These side effects have been associated with depression in patients with advanced breast cancer [16, 17] and their partners [18]. Indeed, studies have shown that male partners of breast cancer patients are concerned about changes in their sexual relationships and that these concerns are exacerbated when the wives’ disease recurs [19, 20]. Although breast cancer including its side effects is a shared problem within the couple [20, 21], little is known about how sexual problems introduced by cancer are associated with couples’ psychological well-being and how couples maintain well-being despite sexual problems.

Generally, sexuality at the end of life had been a neglected research topic. Fairly recently, however, studies in palliative care settings found that loving, intimate relationships including sexual contact remain significant concerns during terminal illness [8, 22, 23] and that sexuality is an important component of holistic care, psychosocial functioning, and overall QOL [24–27]. However, the extent to which sexual problems as a result of cancer are associated with psychological function in couples coping with advanced disease such as MBC is relatively unknown. Even in the literature regarding early-stage disease or other cancer types such as prostate cancer, couples-based studies are relatively rare. Yet, we do know from the existing studies that communication processes play an important role in couples’ psychosocial adjustment to cancer [28–30], including their adaption to sexual dysfunction or problems [31–35].

As couples cope with cancer, they often experience impaired communication about changes to their sexual relationship and sexual problems that may have emerged [36]. This lack of communication is problematic because it may lead to emotional distancing within the couple [37], increasing psychological distress and decreasing marital satisfaction [34]. It may also induce feelings of fear of abandonment in women [38] because patients may feel undesirable to their partners due to treatment-related changes in appearance (i.e., mastectomy) [6]. While partners may sexually withdraw for fear of causing pain or discomfort to the patient, [39] women may withdraw from sexual affection to prevent requests for sexual activity [40]. Importantly, patients’ who report open communication with their partners appear to experience low levels of psychological distress despite sexual problems, as studies in the prostate cancer literature have demonstrated [41, 42].

Although spousal communication patterns can be conceptualized in various ways, studies involving cancer patients and their partners have mainly examined mutual constructive (MC) communication and demand-withdrawal (DW) communication patterns. Open and constructive spousal discussions (i.e., MC communication) about a cancer-related concern seem to be associated with greater marital satisfaction and decreased distress. In contrast, when one member of the dyad exerts pressure to talk about a problem while the other member withdraws or becomes defensive (i.e., DW communication), lower levels of relationship intimacy [32] and marital satisfaction [34] and increased levels of psychological distress [43] are reported. There is also some evidence that these patterns of communication affect patients and spouses differently. For instance, even though MC communication about cancer-related concerns was associated with less distress and more relationship satisfaction in both patients with early-stage breast cancer and their spouses [43], MC communication protected only patients but not spouses against adverse effects of sexual dysfunction associated with prostate cancer [32, 34].

Building on these findings, we sought to highlight the need to study sexual problems in couples affected by advanced disease. More specifically, the purpose of the current study was to examine the association between sexual problems and psychological function (i.e., depressive symptoms) in couples in which the patient initiated treatment for MBC. On the basis of descriptive work and intervention studies targeting communication skills [31, 33, 44, 45], we hypothesized that MC communication and DW communication moderate this association so that only couples who report low levels of MC communication and high levels of DW communication report increased depressive symptoms when faced with sexual problems. We also examined whether the associations between sexual problems, communication patterns, and depressive symptoms differ for patients compared with their partners. On the basis of previous evidence [21, 32, 34], we hypothesized that communication patterns have a stronger buffering effect for patients than for their partners. This current research was intended to extend previous findings involving couples coping with early-stage disease and inform future, couple-based psychosocial interventions addressing the specific concerns of couples coping with advanced disease.

Methods

Recruitment

The current data are from a larger longitudinal study of MBC couples’ adaptation to pain [21, 46] so that all patients in this sample indicated that they had experienced at least some sensation of pain over the last week at the time of recruitment. Patients were eligible if they 1) were initiating treatment for MBC; 2) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of ≤2 (the patient is ambulatory and capable of all self-care but is unable to perform any work activities); 3) rated their average pain over the last week as ≥1 on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [47], which asks participants to rate their pain on a 11-point scale with anchors labeled as “0 = no pain” and “10 = worst pain imaginable”; 4) could speak and understand English; and 5) had a male partner (spouse or significant other) with whom they had lived for at least 1 year.

Research staff approached 343 eligible patients and partners during the patient’s routine clinic visits; 281 couples (82%) provided written, informed consent. Patients who declined participation said they felt too distressed to participate or were not interested. We compared patients who participated with those who declined by using available data on patient age, ECOG performance status, race, average BPI score at the time of recruitment, and primary metastatic site. The only significant difference was for pain t(351) = −8.49, p = 0.001. Specifically, patients who agreed to participate had more pain (M = 4.34, SD = 3.02) than those who declined (M = 1.44, SD = 1.34).

Patients and partners who consented were asked to separately complete paper-and-pencil questionnaires and to return them in individually sealed postage-paid envelopes. All participants received $10 gift cards for survey completion. Despite reminder phone calls, 75 (27%) of the 281 couples did not return the questionnaire, and for 15 couples only one person returned the questionnaire; both the patient and the partner from 191 dyads returned the questionnaire. African American, Hispanic, and Asian patients had a greater likelihood of passive refusal than white patients did (χ2(3, 273) = 5.79, p = 0.02). The final sample comprised 201 patients and 196 partners.

Measures

Sexual Problems

We adapted Majerovitz and Revenson’s [48] 6-item measure of sexual problems, which was originally developed for couples coping with rheumatic disease. Given our dyadic design, this measure not only assesses perceptions of how sexual problems may affect one’s partner but also allows for dyadic level analyses because the items are appropriate for both patients and partners to complete. Commonly used sexual function instruments such as the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [49] tend to assess specific aspects of sexual function (e.g., attaining and maintaining lubrication, ability to achieve orgasm) without taking the participants’ intimate relationship into consideration and tend to be gender specific. Consistent with the sexual concerns frequently reported in the breast cancer literature such as loss of desire and perceived sexual attractiveness and fear of pain [5, 6, 15, 38, 50, 51], the current items focused mainly on sexual desire (e.g., “I enjoy sex less than I used to”) and the negative effect of cancer on the sexual relationship (e.g., “I’m often afraid to have sex to make my [or my partner’s] pain worse”) as opposed to sexual function per se. Study participants rated their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Higher scores indicate greater problems. The internal consistency of this measure was acceptable [52], with alpha reliability coefficients of 0.58 for patients and 0.50 for partners. See Appendix A for the patient and partner versions of the measure.

Spousal Communication Patterns

We adapted the Communication Patterns Questionnaire [53] to be cancer specific by asking participants to rate how the couple typically dealt with cancer-related problems or issues. Mutual constructive (MC) communication consisted of 7 items that assessed mutual discussion of an issue, expression of feelings, understanding of views, and feeling that the issue had been resolved. Demand-withdrawal (DW) communication consisted of 6 items that assessed how often one member of the couple pressured the other one to discuss a cancer-related problem but he or she withdrew and did not want to talk about the concern. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = unlikely to 7 = likely). Higher scores represented greater use of the particular communication pattern. Internal consistency was acceptable to good [52], with alpha reliability coefficients of 0.77 and 0.76 for communication and 0.79 and 0.80 for DW communication among patients and partners, respectively.

Depressive Mood

Participants completed the well-validated 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale [54]. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater distress. A cutoff score of ≥16 indicated “caseness” warranting further psychological evaluation. Internal consistency was good [52] for both patients and partners, with alpha coefficients of 0.89 and 0.90, respectively.

Descriptive Variables

In addition to the main study variables, demographic, medical, and other descriptive variables were assessed.

Demographic and medical variables

Participants reported their race, age, education level, employment status, marital status (married or cohabitating), and length of relationship. Patients also reported on the amount of time since their initial diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, primary metastatic site, and history of medical treatments.

Quality of Life

Patients’ functional and physical well-being were assessed with the respective subscales of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast Cancer (FACT-BC) measure [55]. Patients indicated the extent to which they had experienced each symptom or statement during the preceding 7 days on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 0 = not at all to 4 = very much). Higher scores indicated better QOL.

Relationship Satisfaction

We used the abbreviated, 7-item version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-7) [56] to assess relationship satisfaction among patients and partners. Scores can range from 0 to 36; a score <21 indicated marital distress.

Data Analysis Strategy

We calculated descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations (SD), and correlations) for each of the study variables and performed paired t-tests to determine whether mean scores differed for patients and partners. Considering that martial satisfaction, sexual problem, overall QOL, pain, and depressive symptoms tend to have shared variance in breast cancer patients [4, 12, 16, 38, 57], we controlled for patients’ reports of pain and functional and physical QOL as well as patients and spouses’ relationship satisfaction. To rule out further potential confounds, we tested for significant associations between depressive symptoms and participants’ demographic variables (e.g., age, length of relationship, employment status, education level) and patients’ medical factors (e.g., time since diagnosis, treatment types, stage at diagnosis). If associations were above a significance level of p < 0.10, we included this factors in the main analyses.

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether the level of depressive symptoms in couples experiencing sexual problems depends on the degree to which they engage in MC or DW communication and whether these associations differ for patients and partners. To accomplish these goals, we regressed participants’ depressive symptom scores on the 3-way interaction between sexual problems, communication patterns (i.e., MC or DW), and social role (i.e., patient or partner). Because of the dyadic nature of our data, we used a multilevel modeling technique in which the couple was the unit of analysis [58] by using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS [59]. As opposed to the general linear model, multilevel modeling allows testing of non-independent data without biasing the probability estimates. Significant interactions were probed using simple slope analysis as outlined by Preacher et al. [60]. This procedure was developed specifically for multilevel modeling and allows determining at which level of the moderator (i.e., communication pattern or social role) the focal variable (i.e., sexual problems) is significantly associated with the outcome (i.e., depressive symptoms). Significant 3-way interactions were decomposed by social role, and the association between sexual problems and depressive symptoms was examined at low (mean − 1 SD) and high (mean + 1 SD) levels of the specific communication pattern. On the basis of probability estimates of normal sampling distributions, 32% of scores fall above or below 1 SD of the raw mean. Even though these scores are less likely to be observed compared with the expected mean value, they are useful in interpreting interaction effects [61]. Because the instruments used to assess our focal and moderator variables (i.e., sexual problems and communication pattern, respectively) do not have standardized clinical values to identify extreme cases, standard deviations serve in place of such standardized values. For all analyses, predictor variables were centered at their grand mean [58] and effect coding was used for social role (patient = 1 and partner = −1). For significant effects, effect sizes were calculated using the formula r = [t2/(t2 + df)]1/2 [62].

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and medical characteristics of the sample. Mean CES-D scores were 14.51 (SD ± 9.62) for patients and 13.60 (SD ± 9.76) for partners. Thirty-seven percent of patients, 32% of partners, and 16% of couples met the CES-D score criterion for caseness.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 201) | Partners (N = 196) |

|---|---|---|

| White (%) | 185 (92.0) | 182 (92.9) |

| Age (mean ± SD) (range), yrs | 52.20 ± 10.5 (23–78) | 54.40 ± 10.85 (24–79) |

| College ≥2 yrs (%) | 141 (70.1) | 147 (75.0) |

| Employment status (%) | ||

| Full-time | 50 (24.9) | 131 (66.8) |

| Part-time | 21 (10.4) | 7 (3.6) |

| Unemployed | 63 (31.3) | 8 (4.1) |

| Retired | 52 (25.9) | 46 (23.5) |

| Unknown | 15 (7.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Married (%) | 199 (99.0) | |

| Length of marriage (mean ± SD) (range), yrs | 25.57 ± 13.02 (1–78) | |

| Stage at initial diagnosis (%) | ||

| I | 24 (11.9) | |

| II | 51 (25.4) | |

| III | 41 (20.4) | |

| IV | 51 (25.4) | |

| Unknown | 34 (16.9) | |

| Years since diagnosis (mean ± SD) (range) | 5.43 ± 5.20 (5 wks–25.6 yrs) | |

| Primary metastatic site (%) | ||

| Bone | 113 (56.2) | |

| Lung | 42 (20.9) | |

| Liver | 38 (18.9) | |

| Brain | 8 (4.0) | |

| Treatment (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 171 (85.1) | |

| Hormonal therapy | 22 (10.9) | |

| Palliative radiotherapy | 8 (4.0) |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the means, SDs, and correlations for major study variables by social role. Of note, all partial correlations were significant at p < 0.01, and associations between sexual problems, communication patterns, and depressive symptoms were stronger for partners compared with patients as indicated by larger correlation coefficients. Nonetheless, patients reported significantly more sexual problems than their partners (t150 = 3.01, p < 0.01, paired t-test).

Table 2.

Correlations, means, standard deviations (SDs), and paired t-tests on major study variables for patients and partners

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient (r)

|

Means ± SD (Range)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | Sexual Problems | MC | DW | Patients | Partners | t+ | df | |

| CES-D | .23** | .43*** | −.42*** | .46*** | 14.51 ± 9.62 (0–47) | 13.60 ± 9.76 (0–46) | 1.40 | 175 |

| Sexual Problems | .35*** | .37*** | −.24** | .25** | 2.69 ± 0.71 (1–5) | 2.55 ± 0.61 (1–4.33) | −3.01** | 172 |

| MC Communication | −.20** | −.16* | .34*** | −.59*** | 14.66 ± 9.03 (−15–23) | 14.48 ± 8.29 (−17–23) | .62 | 172 |

| DW Communication | .26*** | .18* | −.44*** | .38*** | 12.22 ± 7.92 (6–38) | 12.64 ± 8.06 (6–38) | .29 | 150 |

Patient correlations are on lower diagonal and shaded in light grey, partner correlations on upper diagonal, and partial correlations are on the diagonal and shaded in dark grey. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale; MC, mutual constructive communication; DW, demand-withdrawal communication.

Paired t-test examined differences in patient and partner scores.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

For patients, the mean BPI score was 4.26 (SD ± 3.03), functional well-being score was 17.69 (SD ± 6.24), and physical well-being score was 17.97 (SD ± 6.48). Previous studies of MBC patients have reported mean scores of average pain on the BPI ranging between 1.7 and 5.31 [12, 16, 17, 63, 64], indicating that the current sample is representative of the MBC population regarding their experience of average pain. Additionally, with respect to functional and physical well-being, our sample was fairly comparable to previous MBC samples [65, 66].

Relational satisfaction mean scores were 25.66 (SD ± 6.24) for patients and 24.80 (SD 5.60) for partners; 22.5% of patients, 21.6% of partners, and 10% of couples met the criteria for marital distress. Relationship satisfaction (patients: p < 0.05; partners: p < 0.001) and patients’ pain, functional well-being, and physical well-being (all p < 0.001) were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. These variables were included as covariates. None of the patients’ medical variables (i.e., time since diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, primary metastatic site, and treatment history) and none of the participants’ demographic characteristics were significantly associated with depressive symptoms; consequently, we did not include those variables in our main analyses.

Multilevel Analysis

MC Communication

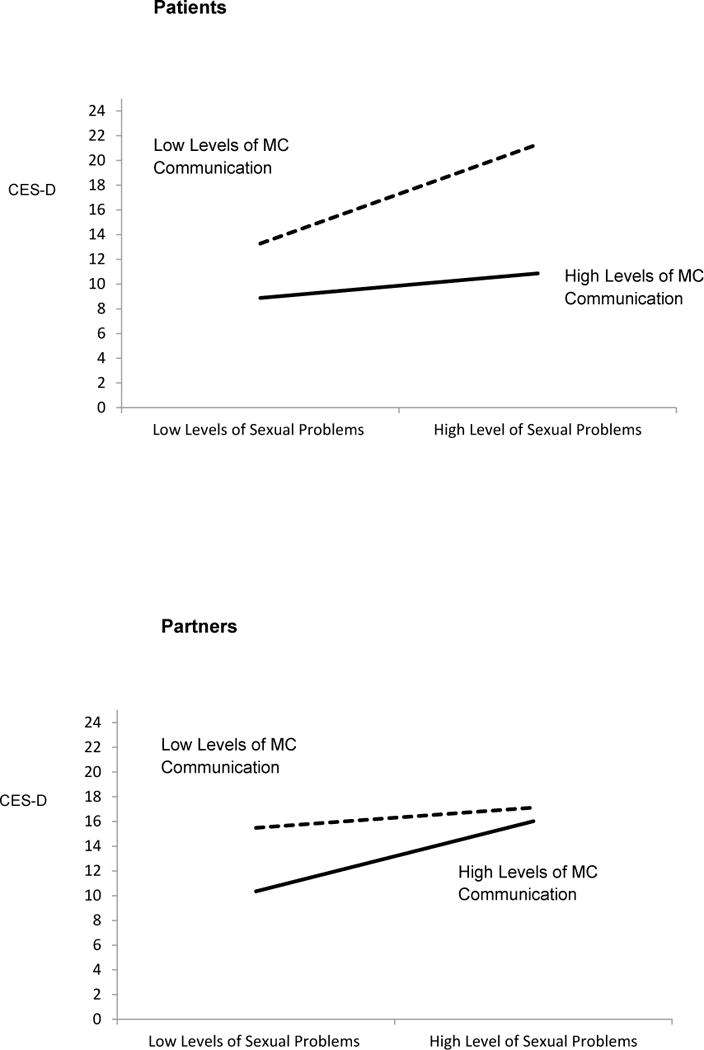

As hypothesized, there was a significant 3-way interaction between sexual problems, MC communication, and social role (F1,309 = 7.46, p < 0.01) (Table 3). Simple slope analyses revealed that, when patients experienced greater sexual problems, they reported greater depressive symptoms if they reported low levels (mean − 1 SD) of MC communication (z = 3.85, p < 0.0001). Patients who reported high levels of sexual problems and high levels (mean + 1 SD) of MC communication did not have increased depressive symptoms (z = 1.00, p = 0.32) (Figure 1, top). Simple slope analyses for partners revealed that high levels of MC communication did not protect against increased depressive symptoms when partners reported high levels (mean + 1 SD) of sexual problems (z = 0.99, p = 0.32). However, when partners reported low levels (mean − 1 SD) of sexual problems, they reported significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms when they reported high compared with low levels of MC communication (z = 3.16, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1, bottom). Because the 3-way interaction was significant, we did not test lower-order terms [67].

Table 3.

Sexual problems, communication pattern, and social role on depressive symptoms

| Mutual Constructive Communication Pattern | Demand-Withdraw Communication Pattern | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| B | SE | T | R | B | SE | t | r | |

| Intercept | 15.96 | 2.46 | 16.71 | .65 | ||||

| Pain | .21 | .16 | 1.29 | .21 | .16 | 1.33 | ||

| Physical well-being | −.07 | .09 | −.75 | −.10 | .09 | −1.05 | ||

| Functional well-being | −.49 | .09 | −5.57*** | .42 | −.45 | .08 | −5.39*** | .40 |

| Dyadic adjustment | −.05 | .09 | −.51 | −.07 | .09 | −.85 | ||

| Sexual problems | 2.65 | .95 | 2.77** | .15 | 2.33 | .93 | 2.50* | .14 |

| Communication Pattern | −.16 | .07 | −2.14* | .12 | .19 | .08 | 2.31* | .13 |

| Social role | −1.24 | .94 | −1.32 | −1.51 | .93 | −1.61 | ||

| Sexual Problems × Communication | .17 | .10 | 1.72 | −.25 | .11 | −2.31* | .13 | |

| Sexual Problems × Social role | 1.03 | 1.42 | .73 | 1.14 | 1.39 | .82 | ||

| Communication × Social role | −.24 | .10 | −2.35* | .15 | .28 | .11 | 2.47* | .13 |

| Sexual problems Communication × Social role | −.43 | .15 | −2.73** | .14 | −.62 | .16 | 3.87*** | .24 |

B, raw coefficient; SE, standard error; Social Role (patient = 1; partner = −1). Effect size r = [t2/(t2 + df)]1/2.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Results of multilevel model analysis revealing a significant 3-way interaction depicting patient (top) and partner (bottom) depressive symptoms as a function of sexual problems and mutual constructive (MC) communication (higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms).

DW Communication

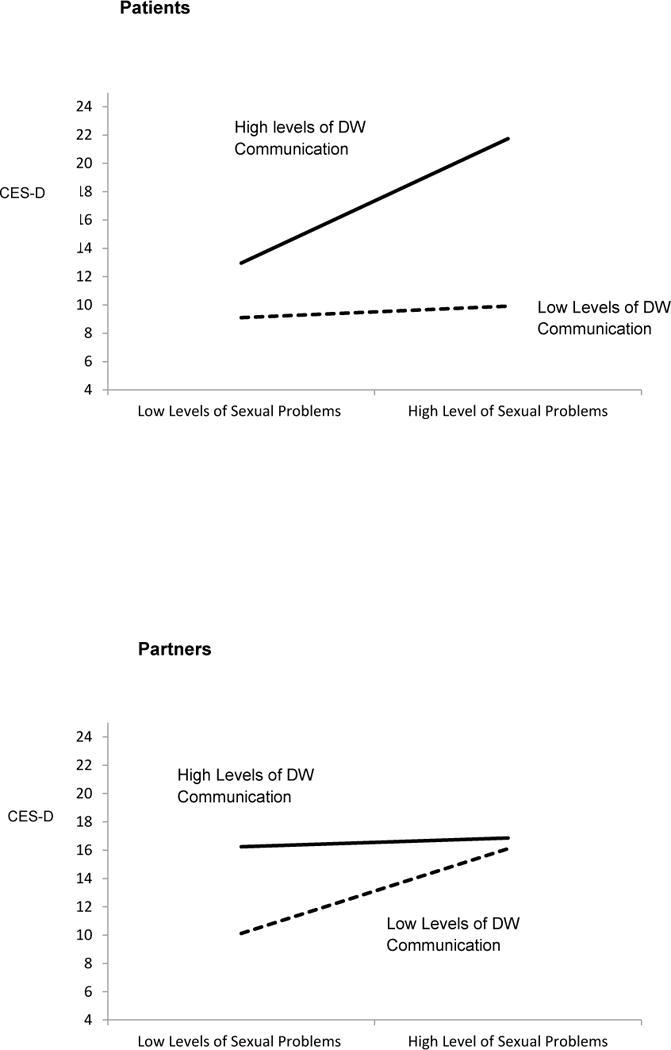

There was also a significant 3-way interaction between sexual problems, DW communication, and social role (F1,304 = 15.20, p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Simple slope analyses for patients revealed that when patients experienced greater sexual problems, they reported greater depressive symptoms if they reported high levels (mean + 1 SD) of DW communication (z = 4.74, p < 0.0001). For patients reporting low levels (mean − 1 SD) of DW communication, greater sexual problems were not significantly associated with increased depressive symptoms (z = 0.40, p = 0.69) (Figure 2, top). Simple slope analyses for partners revealed that low levels of DW communication did not protect against increased depressive symptoms when partners reported high levels (mean + 1 SD) of sexual problems (z = 0.35, p = 0.73). However, when partners reported low levels (mean − 1 SD) of sexual problems, they reported significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms when they reported low compared with high levels of MC communication (z = 3.65, p < 0.0001) (Figure 2, bottom). Again, because the 3-way interaction was significant we did not test lower-order terms [67].

Figure 2.

Results of multilevel model analysis revealing a significant 3-way interaction depicting patient (top) and partner (bottom) depressive symptoms as a function of sexual problems and demand-withdraw (DW) communication (higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms).

Discussion

Our study results suggests that sexual problems are a significant QOL concern among couples coping with MBC, as sexual problems are associated with depressive symptoms in both patients and their partners. We hypothesized that if MBC couples reported more sexual problems but also engaged in higher levels of MC communication, they would be less likely to report depressive symptoms. We further hypothesized that if MBC patients and their partners reported more sexual problems and higher levels of DW communication, they would be more likely to report depressive symptoms. In addition, we expected these associations to be stronger for patients than for their partners. Consistent with our hypotheses, multilevel analysis revealed that patients reporting a high level of MC communication or a low level of DW communication did not report increased depressive symptoms despite experiencing high levels of sexual problems, even after relationship satisfaction, pain, and physical and functional well-being were controlled for. For partners, communication patterns were significantly associated with levels of depressive symptoms when they experienced low sexual problems; however, when sexual problems were high, there was no evidence that the level of MC or DW communication moderated the association between sexual problems and depressive symptoms.

Our results for patients are consistent with previous findings reported for early-stage breast cancer [31, 33] and for prostate cancer [34], suggesting that MC communication processes may facilitate adjustment to cancer-related sequelae such as sexual problems, that DW communication processes may hinder adjustment, and that these processes may be more helpful to patients than to partners [32, 34]. Of note, our study extends these previous findings, emphasizing that sexual problems such as dissatisfaction are important to couples dealing with MBC because the more sexual problems, the more likely they are to experience depressive symptoms.

Our findings also support the idea that even though both members of a dyad may be equally distressed, the factors affecting and maintaining each person’s depressive symptoms may differ. For instance, patients reported significantly more sexual problems than their partners did, but the association between sexual problems and depressive symptoms were stronger for partners than for patients. Furthermore, despite the strong associations between communication patterns and depressive symptoms for partners, MC and DW communication buffered against the association between high levels of sexual problems and depressive symptoms only for patients. Consequently, sexual problems may have stronger implications for partners, who may interpret sexual problems as indicators of deterioration in patients’ health and thus experience depressive symptoms regardless of communication patterns. Alternatively, partners’ need for sexual satisfaction may simply not be compensated for by communication processes. Because the nature of our sample did not allow us to separate the effects of social role from those of gender, this finding may mainly reflect a gender difference such that sexual problems may be more important to men than women in managing emotional distress.

Nonetheless, we emphasize a need for couple-based interventions that address both patients’ and partners’ sexual concerns to alleviate depressive symptoms for both after a diagnosis of MBC. Teaching effective communication patterns characterized by mutual engagement and open exchange of thoughts, concerns, and feelings with the goal of joint problem-solving may be particularly effective components of such programs. In addition to targeting communication skills, interventions that enhance both emotional intimacy and sexual satisfaction may improve psychological adjustment among couples coping with metastatic disease. To date, only a small number of couple-based intervention studies in the cancer literature exist, and an even smaller number of programs target both psychosocial and sexual adjustment. Of note are the studies of Baucom et al. [31] and Scott et al. [33]. In a relationship enhancement intervention involving women with early-stage cancer and their partners, Baucom et al. [31] demonstrated improvements in the sexual drive of both patients and partners compared with couples receiving usual care. The relationship enhancement program targeted dyadic coping, including communication skills training involving mutual disclosing of thoughts and feelings and joint problem-solving. Scott et al.’s CanCOPE program [33] including couples coping with early-stage breast or gynecological cancer also targeted coping and communication skills; however, the authors found improvements in the sexual adjustment of women but not of men. Similarly to these programs, we recommend that, rather than treating problems associated with emotional and sexual intimacy as separate concerns, programs integrate these components in order to alleviate distress in both members of a dyad. On the basis of the current findings, such interventions need to be available to couples coping with advanced disease as well.

Despite the promising findings, our study had some limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional and we cannot rule out a reverse or bidirectional association of the findings. Thus, it is possible that participants who were more depressed reported more sexual problems. Because the current data are part of a longitudinal study, we will be able to examine the directions of these associations in future studies. In addition, the construct validity of the measure we used to assess sexual problems may be debatable due to its moderate to low reliability coefficients. A measure validated for couples coping with breast cancer would have been desirable. Because of the scarcity of dyadic sexuality measures in chronic disease, future research is needed to develop a more appropriate measure. Despite the fairly low reliability of the sexual problems measure, we discovered significant effects, which is remarkable considering that measurement reliability is inversely related to statistical power [68]. Thus, our hypothesis tests were conservative, and future work using a more specific measure may result in larger effect sizes compared with our current findings. Also, we did not explicitly ask if participants were sexually active at the time of survey completion; however, given a response rate of 92% for patients and 88% for spouses on this particular measure, it is unlikely that a response bias based on sexual activity status influenced our results. This study only included heterosexual couples and future research is needed to determine whether these findings generalize to MBC patients with same-sex partners. Last, we assessed how participants discussed cancer-related concerns in general as opposed to sexual problems in particular. We acknowledge that other communication types (besides MC and DW communication) that were not assessed (e.g., mutual avoidance, protective buffering) have been linked to increased psychological distress and may be relevant to managing sexual problems. Thus, future research assessing additional types of communication patterns and patterns that are specific to sexual concerns may build on our groundwork and perhaps explain the role (potentially gender) differences we found. Such research will also be helpful for fine-tuning targets for future studies. Despite these limitations, ours is one of the few studies to have examined sexual problems in MBC, and to our knowledge it is the only study that has included both members of the couple. Because of the data analytic procedure we employed, we were able to not only examine couple-level data within the same model but also test for differential associations for patients and their partners.

In conclusion, this study has laid some important groundwork for a neglected topic in an understudied population. We have demonstrated that sexuality and particularly sexual problems are a concern among MBC couples and are associated with both patients’ and partners’ depressive symptoms. We also examined the role of MC and DW communication patterns and found that high levels of MC communication and low levels of DW communication may protect against depressive symptoms associated with sexual problems in patients but not in their partners. Future interventions targeting communication patterns may alleviate depressive symptoms associated with sexual problems and facilitate couples’ successful adaptation to a chronic and life-threatening disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a multidisciplinary award from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command W81XWH-0401-0425 (Hoda Badr, Ph.D., Principal Investigator).

Appendix A: Sexual Problems Scale adapted from Majerovitz and Revenson [48]

Instructions

Many people with cancer find that their illness has had an effect on their sexual lives. Please circle the response that best describes how you currently feel about each statement.

Patient Version

I am often in the mood for sex. (Reversed scored)

I feel that my spouse is not as interested in sex as I would like him to be.

My illness makes me less sexually appealing to my spouse.

I enjoy sex less than I used to.

I feel like sex is a responsibility, not a pleasure.

I am often afraid to have sex for fear of making my pain worse.

Partner Version

I am often in the mood for sex. (Reversed scored)

I feel that my spouse is not as interested in sex as I would like her to be.

My spouse’s illness makes her less sexually appealing to me.

I enjoy sex less than I used to.

I feel like sex is a responsibility, not a pleasure.

I am often afraid to have sex for fear of making my spouse’s pain worse.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Kathrin Milbury, Department of Behavioral Science, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX

Hoda Badr, Department of Oncological Sciences, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

References

- 1.Sadovsky R, et al. Cancer and sexual problems. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):349–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yurek D, Farrar W, Andersen BL. Breast cancer surgery: comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(4):697–709. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burwell SR, et al. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2815–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barni S, Mondin R. Sexual dysfunction in treated breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(2):149–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1008298615272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fobair P, et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):579–94. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makar K, Cumming CE, Lees AW, Hundleby M, Nabholtz J-M, et al. Sexuality, body image, and quality of life after high dose or conventional chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 1997;6(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karamouzis MV, Ioannidis G, Rigatos G. Quality of life in metastatic breast cancer patients under chemotherapy or supportive care: a single-institution comparative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16(5):433–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordern A, Currow DC. A patient-centred approach to sexuality in the face of life-limiting illness. Medical journal of Australia. 2003;179(6):S8–S11. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauri D, et al. Multiple-Treatments Meta-analysis of Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapies in Advanced Breast Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(24):1780–1791. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg PA, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with complete remission following combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(8):2197–205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler LD, et al. Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on pain in women with metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2009;28(5):579–87. doi: 10.1037/a0016124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palesh OG, et al. A longitudinal study of depression, pain, and stress as predictors of sleep disturbance among women with metastatic breast cancer. Biol Psychol. 2007;75(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosher CE, Duhamel KN. An examination of distress, sleep, and fatigue in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pon.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krychman ML, et al. Sexual oncology: sexual health issues in women with cancer. Oncology. 2006;71(1–2):18–25. doi: 10.1159/000100521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blume E. Sex after chemo: a neglected issue. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(10):768–70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.10.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler LD, et al. Psychological distress and pain significantly increase before death in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(3):416–26. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041472.77692.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koopman C, et al. Social support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Psychooncology. 1998;7(2):101–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199803/04)7:2<101::AID-PON299>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northouse LL, Swain MA. Adjustment of patients and husbands to the initial impact of breast cancer. Nurs Res. 1987;36(4):221–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foy S, Rose K. Men’s experiences of their partner’s primary and recurrent breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2001;5(1):42–8. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2000.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher KA, Lewis FM, Haberman MR. Cancer-related concerns of spouses of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;19(10):1094–101. doi: 10.1002/pon.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badr H, et al. Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):169–80. doi: 10.1037/a0018165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hordern A. Intimacy and Sexuality After Cancer: A Critical Review of the Literature. Cancer Nursing. 2008;31(2):9–17. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305695.12873.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemieux L, et al. Sexuality in palliative care: patient perspectives. Palliat Med. 2004;18(7):630–7. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm941oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stausmire JM. Sexuality at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21(1):33–9. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redelman MJ. Is there a place for sexuality in the holistic care of patients in the palliative care phase of life? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(5):366–71. doi: 10.1177/1049909108318569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilmoth MC. Sexuality: a critical component of quality of life in chronic disease. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(4):507–14. v. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse J, Baldwin MA. Dealing sensitively with sexuality in a palliative care context. Br J Community Nurs. 2008;13(1):20–5. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2008.13.1.27979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manne SB, H Intimacy processes and psychological distress among couples coping with head and neck or lung cancers. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):941–54. doi: 10.1002/pon.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manne S, Badr H, Kashy DA. A longitudinal analysis of intimacy processes and psychological distress among couples coping with head and neck or lung cancers. J Behav Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2541–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baucom DH, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):276–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manne S, et al. Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(1):74–85. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1122–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badr H, Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):735–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AM, Robinson JW, Carlson LE. Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. Urol Oncol. 2009;27(2):137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cytron S, Simon D, Segenreich E. Changes in the sexual behavior of couples after prostatectomy. A prospective study. European Urology. 1987;13(1–2):35–38. doi: 10.1159/000472733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ofman US. Sexual quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 1995;75(S7):1949–1953. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anllo L. Sexual life after breast cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(3):241–8. doi: 10.1080/00926230050084632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cagle JG, Bolte S. Sexuality and life-threatening illness: implications for social work and palliative care. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(3):223–33. doi: 10.1093/hsw/34.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henson HK. Breast Cancer and Sexuality. Sexuality and Disability. 2000;20(4):261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canada AL, et al. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2689–700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maliski SL, Heilemann MV, McCorkle R. Mastery of postprostatectomy incontinence and impotence: his work, her work, our work. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(6):985–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manne S, et al. Cancer-related relationship communication in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(3):234–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chambers SK, et al. ProsCan for Couples: randomised controlled trial of a couples-based sexuality intervention for men with localised prostate cancer who receive radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott JL, Kayser K. A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women’s sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15(1):48–56. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badr H, Milbury K. Associations between depression, pain behaviors, and partner responses to pain in metastatic breast cancer. Pain. 2011;152(11):2596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cleeland C, Syrjala K. How to assess cancer pain. In: Turk D, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. Guilford Press; New York: 1992. pp. 362–387. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Majerovitz SD, Revenson TA. Sexuality and rheumatic disease: the significance of gender. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7(1):29–34. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crandall C, et al. Association of breast cancer and its therapy with menopause-related symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11(5):519–30. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000117061.40493.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wimberly SR, Carver CS, Antoni MH. Effects of optimism, interpersonal relationships, and distress on psychosexual well-being among women with early stage breast cancer. Psychology and Health. 2008;23(1):57–72. doi: 10.1080/14768320701204211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortina JM. What Is Coefficient Alpha – an Examination of Theory and Applications. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78(1):98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christensen A, Shenk JL. Communication, conflict, and psychological distance in nondistressed, clinic, and divorcing couples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(3):458–63. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brady MJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spanier G. In: Dyadic Adjustment Scale. C.M.-h.S. Inc, editor. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giese-Davis J, et al. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):413–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating Actor, Partner, and Interaction Effects for Dyadic Data Using PROC MIXED and HLM: A User–Friendly Guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(3):327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Oaks; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao JJ, et al. Feasibility trial of electroacupuncture for aromatase inhibitor–related arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8(2):123–9. doi: 10.1177/1534735409332903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen J, et al. Palliative response and functional interference outcomes using the Brief Pain Inventory for spinal bony metastases treated with conventional radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23(7):485–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.01.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abernethy AP, et al. Phase 2 pilot study of Pathfinders: a psychosocial intervention for cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(7):893–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0823-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sherrill B, et al. Quality of life in hormone receptor-positive HER-2+ metastatic breast cancer patients during treatment with letrozole alone or in combination with lapatinib. Oncologist. 2011;15(9):944–53. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hays WL. Statistics. 4. Orlando, FL: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosenthal R. Methodology. In: Tesser A, editor. Advanced Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]