Abstract

American Muslims represent a growing and diverse community. Efforts at promoting cultural competence, enhancing cross-cultural communication skills, and improving community health must account for the religio-cultural frame through which American Muslims view healing. Using a community-based participatory research model, we conducted 13 focus groups at area mosques in southeast Michigan to explore American Muslim views on healing and to identify the primary agents, and their roles, within the healing process. Participants shared a God-centric view of healing. Healing was accessed through direct means such as supplication and recitation of the Qur'an, or indirectly through human agents including imams, health care practitioners, family, friends, and community. Human agents served integral roles, influencing spiritual, psychological, and physical health. Additional research into how religiosity, health care systems, and community factors influence health-care-seeking behaviors is warranted.

Keywords: culture / cultural competence, focus groups, healing, model building, religion / spirituality

Culture shapes individuals' notions of health, their understanding and perception of illness, their beliefs about health risks, and their expectations of the doctor–patient relationship (Bennstam, Strandmark, & Diwan, 2004; Fukuhara et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 1999; Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, 1978; Nielsen, Hoogvorst, Konradsen, Mudasser, & van der Hoek, 2003). Culture also influences patients' adherence to doctors' recommendations and health outcomes [AU Q: 1] (Fukuhara et al.). Hence, understanding the influence of patient and health care provider cultures on the health care encounter is integral to delivering optimal health care, and inadequately accounting for divergent cultural frames has multiple consequences for the patient–doctor relationship.

For example, different conceptualizations of disease and cure can lead to unmet expectations for both parties, because clinicians tend to focus on disease states and optimizing biological markers to improve patient health; yet, patients more often view the health care encounter through a different lens, and focus on reducing the burden of the illness, which is interpreted to stem from both disease and the side-effects of medicine. Thus, issues of patient adherence can arise from potentially competing cultural frames of disease and illness. Furthermore, cultural conflict and ethical challenges can arise from competing value systems (Kleinman et al., 1978). For example, a patient might view cervical cancer screening as a challenge to modesty, whereas the clinician might view this procedure as essential to disease prevention. The resolution of these conflicts bears significance for the patient's future health-care-seeking behavior.

On a community level, some ethnic groups might forgo treatment because of different concepts of illness, and delay treatment because of cultural conflicts, experiences of discrimination, and lack of clinical accommodation (Kleinman et al., 1978; Malat & van Ryn, 2005). Therefore, assessing the cultural values and practices around health and healing within patients' specific ethnic, racial, and religious communities is important for enhancing community health (Hartog & Hartog, 1983; Kleinman et al.). For some communities, religious beliefs, practices, and values form an integral part of their cultural identity. With regard to interactions with the health system, religion can inform expectations of health care providers, guide medical decision making, and influence adherence to medical treatment (Fukuhara et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 1999; Nehra & Kulaksizoglu, 2002; Nielsen et al., 2003). Thus, for some patient populations, their religious values serve as an important alternative entry point, beyond the biomedical model, for developing and articulating meanings of health and understanding health practices and choices (Yehya & Dutta, 2010).

American Muslims are one such community, that although diverse ethnically and racially, is bound together by a shared religious tradition that shapes its members' worldview and informs their behaviors. Estimates of the American Muslim population vary widely because of methodological challenges, such as the inherent difficulty of assuming Islamic affiliation based on naming algorithms and country-of-origin proxies, and sociopolitical factors such as the decreased overt self-identification as Muslim in a post-September 11, 2001 world. Nonetheless, the average estimate is 5.4 million, with more recent sources citing a figure closer to 7 million (Ba-Yunus, 1997; Obama, 2009; Smith, 2002). The major ethnic groups within the American Muslim community are indigenous African Americans, South Asians, and Arabs (Allied Media Corp., n.d.). This diverse community might share religiously informed views on health, illness, and the healing process, which might manifest in similar health behaviors and health-care-seeking patterns.

Systematic research on the influences of Islam on American Muslim health behaviors is challenging. Population-based representative samples of the American Muslim community do not exist because most national health care databases do not adequately capture religious affiliation, and naming algorithms used for proxies have not been fully validated. Although the qualitative literature does capture some Islamic influences on American Muslim health values and behaviors, most of these studies were focused only on one ethnic group within this diverse community (Beine, Fullerton, Palinkas, & Anders, 1995). We are not aware of an empirical study that drew from multiple groups within the American Muslim community to assess views on the healing process and the agents within that process.

Understanding conceptual models of well-being, health, and disease within this diverse community is a first step toward providing patient-centered care and designing culturally sensitive health promotion programs, as the types of explanatory models held by patients influence their receptivity to and expectations from medical care, health-promotion messaging, and their preventive and treatment-seeking health behaviors (Healey-Ogden & Austin, 2011; Kreuter & McClure, 2004; Maier & Straub, 2011; Milat, Carroll, & Taylor, 2005). Thus, giving voice to the patient perspective on healing will help health care providers understand the American Muslim worldview and negotiate health-promoting behaviors and medical treatments within their cultural frames. Indeed, the Institute of Medicine (2002, 2003) has called for culturally targeted health messages and interventions to take account of patient explanatory models of health, illness, and disease. Furthermore, there might be community agents and social support mechanisms that American Muslims use within healing that can be used to promote community health and holistic medical care.

The extant literature provides some insight into how American Muslims view health. In a study of immigrant Pakistani families, conceptions of health were reported to include social, spiritual, and physical domains. The authors noted that the acceptance of medical treatments was mediated by a sense of concordance within this holistic conception of health (Jan & Smith, 1998). In a similar fashion, Afghan American elders residing in California reported their health being tied to Islamic adherence, and thus used various religious practices as a means for healing (Morioka-Douglas, Sacks, & Yeo, 2004). In a study of South Asian Americans, Muslim participants consistently evoked spiritual factors such as performance of prayer as health promoting (Tirodkar et al., 2010). Similarly, in a study of Somali immigrant women, participants shared spiritual explanations for illness and reported that discordant health beliefs between themselves and their providers often led to misunderstandings, a lack of trust, and unmet expectations (Pavlish, Noor, & Brandt, 2010).

In terms of agents in healing, multiple researchers noted that Muslims view God as the one who ultimately controls health and illness (DeShaw, 2006; Ypinazar & Margolis, 2006). Illustratively, researchers explored South Asian women's views on breast cancer. Among other causative factors, the women reported that God determines who develops breast cancer and who is cured. Their view that breast cancer was a “disease of fate” influenced their health-care-seeking behaviors because some believed they were destined to suffer, whereas others felt their fate could be changed through prayer and seeking medical care (Johnson et al., 1999; Rajaram & Rashidi, 1999). Arab American immigrants in New York also echoed the belief that cancer was from God, and modifiable risk factors were secondarily implacable, giving voice to a potentially fatalistic attitude (Shah, Ayash, Pharaon, & Gany, 2008). Finally, imams, or Muslim religious leaders, have also been shown to play key roles in American Muslim community health, because they are perceived as counselors and a source of spiritual cures (Abu-Ras, Gheith, & Cournos, 2008; Padela, Killawi, Heisler, Demonner, & Fetters, 2010).

Given the need to better understand the influence of Islam on American Muslim behaviors and practices, we conducted a community-based participatory research project involving segments of the African American, Arab American, and South Asian American Muslim communities. In this article, we specifically address three questions for American Muslims: What role does God play in the healing process? Who are the agents in healing? What roles do they play? By analyzing these questions, we construct a conceptual model that illustrates an American Muslim view of healing.

Increased understanding of how American Muslims view healing can help health care providers better situate medical interventions within an American Muslim cultural frame, as well as provide insight into structures outside of the allopathic system that play a role in healing for this community. Thus, our work can be placed within efforts to enhance cultural competence. Cultural competence has been shown to reduce negative stereotyping of minority patients and to enhance cross-cultural communication (Beach et al., 2005). Effective training efforts aim to instill a commitment to working to minimize the negative consequences of cultural differences in medical care (Paasche-Orlow, 2004). Thus, by appreciating the “healing” views of Muslims, health care providers might be able to avoid issues of nondisclosure of alternative treatments and prevent nonadherence with allopathic therapies. On a macro level, by identifying partners in healing and collaborators for targeted interventions, our findings have clear implications for improving community health.

Methods

Setting

We conducted this study in southeast Michigan, home to one of the longest-standing and largest populations of American Muslims in the United States. This community is estimated to number around 200,000; however, measurement is complicated by several methodological challenges and the lack of recent survey data (Arab American Institute Foundation, 2003; Hassoun, 2005; Numan, 1992).

Design

We used a community-based participatory research model by partnering with four community organizations in southeast Michigan: two Islamic umbrella organizations representing more than 35 Muslim entities including more than 25 mosques, an American Muslim policy institute, and an Arab community health organization. Representatives from these organizations, along with a multidisciplinary investigative team, comprised a steering committee that guided all phases of the project, from research question and interview guide development to sampling and participant recruitment, data analysis, and dissemination (Israel, Eng, Schulz, Parker, & Satcher, 2005). The investigative team included various experts including a Muslim physician/researcher with expertise in Islamic bioethics, a social worker active in several Muslim advocacy organizations, experienced qualitative researchers, a senior health services researcher, and a nurse investigator with research experience within this Muslim community.

We used a two-phase design. Phase 1 involved interviews with community stakeholders who held different positions within the Muslim community, and who represented a variety of different ethnicities, races, countries of origin, and theological sects (Padela et al., 2010). Participants in Phase 1 identified influences of Islam on health care behaviors and provided foundational themes to explore in the Phase 2 focus groups with community members. This project was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Sampling and Data Collection

We conducted 13 focus groups at seven mosques in southeast Michigan chosen purposefully to achieve variation on race, gender, and ethnicity, and to allow for adequate representation of Arab Americans, South Asian Americans, and African Americans. Of the 13 focus groups, 11 were held at predominately Sunni mosques, and two at a predominately Shiite mosque. The focus groups were conducted between December of 2009 and March of 2010. The focus group technique was used to allow “sharing and comparing” of views, and to probe for areas of common concern to the greater community (Morgan, 1997). The focus group guide was based on themes found during Phase 1 data collection and carefully constructed to have broad applicability to the participants. Our steering committee, comprised of Muslim community members across the ethnic and theological divides, aided in carefully constructing questions of relevance to men and women, Sunni and Shiite, African and Arab alike.

Given that our aim was to better understand the religious influences on health care behaviors, mosque-based recruitment was chosen as a proxy for self-identification with Islam and base level of religiosity. Each mosque governed the manner in which participant recruitment occurred. Thus, adult participants older than 18 years were variably recruited via banners on mosque Web sites, flyers on mosque community boards, announcements made at mosque events, or personal contact by mosque representatives serving on the community steering committee. Focus groups lasted 1.5 to 2 hours, were segmented by gender and language preference (Arabic vs. English), and were moderated by a multilingual, gender-concordant member of the investigative team (Padela and Killawi). Participants were asked about American Muslim health beliefs, challenges, and behaviors. Questions most relevant to this article included: Why do people become ill? What role, if any, does the family play in healing? What role, if any, do health professionals play in healing? What role, if any, do imams play? Is there anyone else you depend on for healing?

Think back to your experiences with health care professionals. How have these been for you? Does anyone have an experience they would like to share?

Data Analysis

Interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Because respondents sometimes spoke in Arabic, Arabic terms were translated into English by a bilingual team member and verified for accuracy by a second bilingual team member. The transcript of the one focus group in which participants spoke only Arabic was translated by a professional translation company and verified for accuracy by a bilingual team member. Qualitative content analysis was used to identify common themes, drawing on principles of grounded theory, including constant comparison of participant responses and inductive identification of themes from the data in a team-based approach.

Four analysts (Padela, Killawi, DeMonner, and another team member) immersed themselves in the data by reading and open coding the transcripts independently and developing preliminary codes. This group then met regularly to discuss emerging themes and to refine code definitions, with periodic input from the entire research team, until agreement was reached on codes and their definitions. Using the final codebook, two analysts (Killawi and another team member) independently coded and compared coding of three transcripts, resolving disagreements through consensus meetings with the PI (Padela). Each of the remaining transcripts was coded by a single coder using the final codebook. We used NVivo 8 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2008), a qualitative data analysis computer software application, to facilitate analysis.

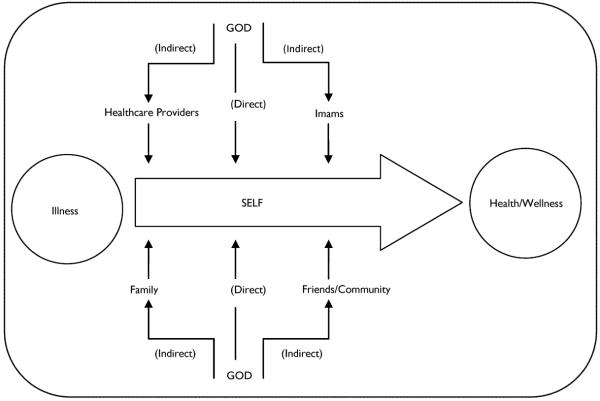

Each transcript was assigned an analyst to develop a summary by code and to begin grouping codes into higher-order conceptual themes. These summaries were used in team meetings to identify common themes and subthemes across interviews, and to integrate these themes into a conceptual model of the agents and their roles in the healing process. The validity of our findings was enhanced by detailed data from focus groups, rigorous code development, use of a group consensus process that included reflexive discussion of the data to develop findings, and a multidisciplinary research team. Through our analysis of the findings we construct a model that illustrates how American Muslims view the healing process, as well as identify the major agents within that process (see Figure 1). We present the common themes across focus groups.

Figure 1.

Agents & Roles in Healing

Findings

Focus Group Demographics

The 13 focus groups were comprised of a nearly equal number of women (n = 7, 54%) and men (n = 6, 46%). Four focus groups were predominately of Arab participants, three of South Asian members, two of African American respondents, and four were of mixed ethnicities. The number of participants in each focus group ranged from 4 to 12, with a mode [AU Q: 2] of 9. There were a total of 102 participants (56 women, 46 men) in the focus groups. They ranged in age from 18 to 75 years, with a mean of 45 years. Most participants identified as Sunni (n = 81, 82%), with 7 (7%) identifying as Shiite and 8 (8%) preferring not to share their denomination. Forty-three percent of participants were Arab American (n = 43), 23% South Asian (n = 23), and 22% African American (n = 22). The majority of participants had health insurance (n = 76, 75%), and more than half reported completing at least a bachelor's degree (n = 53, 53%).

Agents and Their Roles in Healing

Participants' viewed their overall health as having multiple components: spiritual, physical, and mental. They identified multiple actors who performed ameliorating functions within one or more of these domains of health to move from a state of illness to well-being. God was viewed as having the preeminent role in health because His decree leads to disease and feeling ill, as well healing and maintaining health. The human agents identified in the healing process included imams (n = 13), family members (n = 12), health care providers (n = 12), and friends and the greater community (n = 5). Below, we describe these actors and their roles.

The role of God in health and healing

In nearly all focus group discussions (n = 11), participants noted God's central role in the process of healing. Participants expressed their belief that “God … is the ultimate doctor. He is the one that brought down the disease. He is the one that brought down the cure”; “healing is in the hand of God before everything.” Illness from God could be interpreted in several positive ways; one participant explained:

A person … should not feel sad inside and wonder why he became ill. … Everything is from Allah [God]. First, it's predestined … to become ill. … Second, … Allah Almighty has shown kindness toward this servant by making him ill, and he shall be rewarded [for] that illness.

God's direct role

God was seen to play a direct role in facilitating healing. To directly seek healing from God, participants engaged in a variety of religious rituals such as supplication or du'a, and reciting from the Qur'an, Islam's holy book. For example, participants in some focus groups (n = 5) described the healing power of supplication, saying, “It's not always … the medicine, it [is] just the du'a and connect[ing] to Allah, and that will heal it. And we think it's coming from the medicine; actually, no, it's not. It's coming from the du'a.” Another participant described seeking healing through the Qur'an by placing her hand on the location of the illness and reciting certain verses, saying, “I always make myself feel [better] … when [I] keep reciting over the pain.”

God's indirect role

Participants also acknowledged that God can promote indirect healing through the actions of various human agents such as health care providers, family members, community members, and religious figures. For example, participants in the majority of focus groups (n = 9) noted the duty to take care of one's body and consult physicians when ill. Citing a prophetic tradition, a man in the South Asian focus group stated, “I mean, it's one of those … `tie the camel' kind of things. … If you are sick … go to the hospital.” Another respondent advised,

Take what Allah provides on earth; like He provided doctors, He provided medicine, and think—He put it in the back of your mind that it's not the doctor that is curing you, or the medication: it's Allah. … You have to utilize what Allah made accessible to us [physicians, medicine] … along with prayer.

In the majority of the focus groups (n = 8), participants described health care providers as “tools” or “instruments” of God, and expected them to be cognizant of this role. One participant shared an example of how a Muslim physician might articulate his role to his Muslim patients:

So the healing is in Allah's hands; … The medicine which … I'm prescribing is from the best of my knowledge, but Allah is going to give you the healing, so don't say that I'm giving you the healing, but [that] Allah is.

Another participant found it troubling when medical providers did not demonstrate this humble attitude:

I've had difficult moments with [medical] people. … I think that people who are very intelligent [and] have the ability to do health care of any kind can sometimes get a little arrogant … and they don't see that they are an instrument of God.

Two focus group discussions reflected the belief that God provides social support to advance healing. As one participant stated, “Allah will always send you the spiritual family that will be there … and just those little things means so much when you're down.” Another participant explained, “Then again, on the flip side, what if you don't have that support? … Allah's going to make sure that you have that connection with Him alone.”

The role of the imam in healing

All of the focus group discussions identified important roles for the imam in healing, such as delivering health care messages, providing spiritual support and healing, counseling patients, serving the needs of Muslims patients, and educating non-Muslim staff in the hospital. Participants in nearly all of the focus groups (n = 12) noted the crucial role imams play in providing health-based messages grounded in the Islamic tradition. Imams help shape their congregants' attitudes toward coping with illness, and toward health care, by motivating them to take care of their bodies as a religious obligation. One participant explained, “The imam is indeed useful when he gives advice. If a person has a certain disease, it's a trial from Allah Almighty. He is rewarded for it, and Allah compensates him. You become relieved, and the disease becomes lighter.”

Furthermore, imams can encourage their congregation to pay attention to cleanliness and other healthy habits by using illustrative examples from the Islamic tradition. One participant shared,

The imam can [have] a good influence on the community, and he can [give] the message … how to take care of your body, especially the cleaning part of your body. … I think that this … help[s] the community stay healthier. So if he is giving … you advice on washing your hands in a good way and conducting ritual ablution in a good way … it's proven [that] this is a major prevention from any flu or … many kinds of contagious disease[s].

The belief that imams also provide spiritual support and alternative practices for healing was expressed in the majority of the focus groups (n = 10). For example, imams' supplication, especially in congregation, held an important healing quality. Additionally, imams reportedly taught ill congregants specific prayers and litanies to recite, and advised them on prophetic practices that promote health.

The counseling role of the imam, sometimes as a substitute for mental health professionals, was identified in a majority of the focus groups (n = 9). Respondents described the imam as “a counselor for moral support,” and as someone “in whom everybody confides,” because “sometimes people [do not] want to go the psychiatrist,” and they “go to a person that is … religious and knowledgeable [and] … find consolement [AU Q: 3].” Cognizant of imams' limitations in training, respondents shared that imams referred some individuals for formal treatment, yet communities' needs forced imams into being jacks of all trades. One respondent stated,

A lot of pressure is put on the imam to be … everything: the counselors, the doctors, the lawyers, everything. And what's unfortunate, the imams say this themselves. They're not … necessarily trained for those things. … For example, for psychological counseling, you need to see … a professional counselor … An imam is there to give … Islamic advice and tell you [about] the Islamic perspective.

Finally, some focus groups (n = 5) discussed the important roles imams can play in the hospital. Participants noted that imams are needed to “help … educate the staff … [and] facilitate[e] … our [Islamic] practices” to promote culturally sensitive care, and enable the “whole culture of the hospital … [to] be more accommodating to Muslim needs.” Participants explained that imams could establish formal Friday prayer services within the hospital and provide religiously based ethical guidance during critical aspects of medical care. Summing up the need for the Muslim community to be represented in pastoral care, a participant emphatically stated, “I really wish there were imams that would come to the hospital. … Every other religion does [have religious leaders in hospitals]. … We [Muslims] always get [non-Muslim] chaplains in the hospital.”

The role of the family in healing

Participants identified the following four roles of the family: providing physical care, providing emotional support, providing spiritual support, and mediating interactions with the health care system. In nearly all of the focus groups (n = 11), participants discussed the importance of the family in addressing physical needs. Participants explained that family members nurse their ill and administer home remedies. A participant connected the importance of the family with the Muslim faith:

Being Muslim, we are … family oriented. So when somebody is sick in the family, it's the responsibility of the rest of the family to take care of this person and … provide for him, not only the physical environment, but also to give him good food and nutrition and support, and … make him feel comfortable as much as he can.

This role often extends into the hospital, as well as family members who “stand by your [i.e., the patient's] side” to provide additional help such as bringing water and taking the patient to the bathroom when nursing care is unavailable. In nearly all of the focus groups (n = 11), participants also believed that the family promotes psychological health. One participant shared, “Having family support can enhance your recovery and give you a reason to live. … It's inspiration.”

Nearly half of the focus groups (n = 6) also discussed the role of the family in providing spiritual support. Family members reportedly facilitate the patient's worship practices; for example, by giving them Qur'ans to read, reminding them of special prayers to recite for illness, taking them to the mosque, and helping them to bear the burdens of illness. One participant explained, “My son has asthma and he goes, `Mom, why is this happening to me?' … I [tell him], `Say praise be to God. … When you say [that], God makes it easier.'” Additionally, family members engage in their own worship practices to facilitate healing for the patient, mainly by making supplication. One man summarized the role of the family by saying, “God gave you your family to support yourself. … If they are not there … the consequences are different. The results are different.”

In the majority of the focus groups (n = 8), participants highlighted the role of the family in mediating interactions with the health care system. For example, family members might recommend or discourage certain treatments based on shared values with their relatives.

The role of health care providers in healing

Participants discussed the role of health care providers in the healing process in nearly all of the focus groups (n = 12). Participants described their experiences with and their expectations of health care providers. Providing clinical care was the obvious role identified for health care providers, yet participants discussed their unmet needs related to communication and education by health care providers, and noted deficiencies in health care providers' collaborating with them to accommodate their religious and cultural practices. For example, participants expected allopathic providers to take account of their holistic worldview. A participant emphasized this by saying,

I think the doctor should be more … holistic, and not in terms like this is your only option, you know. Keep it open. Give the alternatives. Some doctors don't accept … if you say, “I want to try this.”

It was expected that health care providers respect Islamic religious and cultural values, as noted in two focus groups. Providers were expected to be “facilitator[s] rather than … block[s],” by allowing families to be involved in patient care, accommodating religious mandates such as modesty, and recognizing spiritual practices such as prayer and drinking holy water. One participant explained:

It's not as if the patient … has to say … “Pay attention. I am a Muslim woman, and I have this modesty issue.” … The nurse should be culturally sensitive … and research [this issue] … like she researches [the desires of] a Jehovah's Witness … not to take blood.

Another participant, a retired nurse, discussed how health care professionals should “go the extra mile” to “incorporate religious practices for patients, saying, `This is the problem in … health care. They don't make the effort to respect your culture.'”

Effective communication was an expectation that was also variably met by health care providers. In some of the focus groups (n = 5), participants explicitly mentioned physician communication positives and negatives. One participant mentioned that in comparison to doctors in his home country, American doctors “try to understand and listen well … and are … empathetic,” thus making them more in line with the “Islamic way” of being “compassionate.” Yet, others shared their frustration about interacting with providers who rushed them and didn't listen to them, saying, “I don't know what it is about some of them, but it just seems like they're so above you.”

Participants in some focus groups (n = 5) expected better education from their providers in terms of disease processes and medications. Participants expected their providers to educate them in understandable language and “in a better way than the Reader's Digest [a popular American magazine] does.” In their role as educators, health care providers should also “give advice and direction” and discuss preventive health care. As one person commented, “I think a good doctor is one who is into keeping you healthy, and they're going to talk to you about preventive kinds of things.” These gaps in education and communication were voiced further as a few participants in multiple focus groups perceived physicians to be “pushing … drugs” and scheduling unnecessary visits and tests.

The role of friends and the community in healing

In some of the focus groups (n = 5), the two main roles that emerged for friends and the community were providing emotional support and spiritual support. Participants in these groups described caring for the ill as a communal responsibility. One participant explained, “It is … our obligation when somebody is sick—it doesn't matter if you know that person or not—you have to give them support. Sometimes, there [are] people who have nobody.”

In some of the focus groups (n = 5), participants noted that just like family members, friends and community members also provide emotional support to the sick by visiting them and providing encouragement and positive reinforcement. One participant described an initiative in which “old timers from the community go and meet the [sick] people,” noting that “it makes a big difference … [that] brother so-and-so came to visit. … Our community is good.” One woman noted the importance of the community in providing moral reinforcement for the ill, and explained that this occurred in her particular community: “A society is supposed to stand by the sick person and never let him feel that he is ill or that he is handicapped. Thank God this spirit [of not making him feel ill] exists among us [Muslims].”

Participants also emphasized the importance of friends and community in providing spiritual support. A participant said she found comfort in connecting with her brothers and sisters in faith. Another participant described the necessity of a “prayer partner” during her illness, saying that when her “sister” prayed with her, she “[could] feel the healing right there over the phone.”

The role of the individual in healing and interacting with the health care system

The ultimate determination of the extent to which American Muslims rely on each of these actors in their healing processes is based on perceived need, availability of the agents, illness acuity, and patterns of individual behavior. Hence, great variability exists in patterns of individual behavior. Although participants in the majority of focus groups (n = 8) noted the importance of visiting the doctor and taking medication in conjunction with using prayer, some respondents felt reticent about going to allopathic providers, and viewed religious-based therapeutics more favorably. For example, a participant shared,

I, for years, have done my own doctoring. … I just feel like they [physicians] want things from me that I don't want for my body, and they don't know my God, so I … look into prophetic medicine.”

In a similar vein, another participant shared her healing practices after being diagnosed with an ulcer:

Six months I did not take a single pill for my stomach. … I took care of myself by reciting the Quran, prayers, and ginger. I seek forgiveness from Allah, and I thank Him; I feel comfortable.

Participants also discussed using alternative or complementary treatments in conjunction with or in lieu of allopathic medicines. For example, a participant shared her experience of being diagnosed by her doctor:

My doctor tells me that I have an enlarged liver … a fatty liver. … He says, “And I want you to take [Vitamin] A, B, C, and D.” I said, “Well, you know what doctor? I don't believe in medication. So here's what I'm going to do. … I'm going to go to the health food store, and I'm going to go find something to clear up this fatty liver, because I'm not taking your zircoff.” … So that's exactly what I did. I took no medication. None whatsoever.

Some participants treated the patient–doctor relationship as analogous to a customer and a merchant, selecting from diagnostics and treatments the physician offered based on personal preference. One woman stated that she had a “very cool” doctor who allowed her to make her own decisions:

Every time I go in there, she has this list that she goes through: “So you won't get a colonoscopy?” “No.” “You won't get a mammogram?” “No.” “You won't get any drugs?” “No.” “You won't get anything?” “No.” “Any blood work?” “No.” I say to her, “If it ain't broke, I ain't going to fix it.”

Many focus group participants noted a deliberative process of consulting family, friends, and other resources before accepting the advice of a physician. For example, one participant offered her recommendation for how to interact with physicians:

I just learned the hard way … [to] go online, put your symptoms—there's like WebMed … Put your symptoms and they will give you a list … so when you … go to the doctor you can give them what you think is wrong with you. Tell them [to] try this and that.

Another participant added that it is important to

not just accept … everything [from doctors] as … law. … They call it doctor's orders, but it's more like recommendations or it's their opinion. … Ultimately, as the patient, you have the final word and the power to decide. … Am I going to listen to him, or am I going to go to somebody else, or am I going to do what I think needs to be done?

A participant summarized this point by saying, “I know my body. I know what hurts me, what doesn't hurt me. … You have to do some self-exploration yourself, along with a professional, and then make the choices.”

Discussion

Through analysis of these focus groups involving the major ethnic groups within the American Muslim community, a conceptual model emerges of the key agents in healing (see Figure 1). The participants related a God-centric narrative wherein God's will was manifested in the granting of good health or the plight of illness. Moving from illness to health was said to require the individual to seek God's cure directly through prayer, supplication, and recitation of the Qur'an, or indirectly through human agents, and sometimes both. The indirect means of restoring health are found through imams, family members, health care providers, and one's friends and community. Each agent is viewed as God's instrument, and has various roles within the healing process.

The imam is a central figure in American Muslim health, delivering health care messages framed within an Islamic worldview in lectures and sermons, counseling the distressed, providing spiritual support, and facilitating healing through communal supplications or the prescription of Qur'anic litanies. Within the hospital, they visit sick Muslim patients, aid in patient-provider-family discussions about health care, and serve as religious “translators” and cultural brokers (DeVries, Berlinger, & Cadge, 2008). These roles are similar to but distinct in scope from those of Muslim chaplains. The family also serves an important role in health restoration. They provide physical care and emotional and spiritual support while also mediating interactions with the health care system. In obvious fashion, allopathic health care providers provide clinical care and are expected to communicate and educate patients in a respectful manner, as well as facilitate their religious and cultural traditions. Finally, community members and friends help facilitate healing by providing emotional and spiritual support. In this way, the participants illustrated how the American Muslim community maintains a holistic vision of healing, and identified several key actors outside of the allopathic system that influence spiritual, physical, and psychological health.

Our findings affirm those of other researchers working with diverse segments of the American Muslim community. Researchers working with Somali immigrants, South Asians, and Arab Americans found these groups to have a holistic conception of health that incorporated social, physical, and spiritual domains. Therefore, in this population, illness might be interpreted as related to spiritual dissonance, and religious practices can be viewed as ameliorating illness and promoting health (DeShaw, 2006; Jan & Smith, 1998; Morioka-Douglas et al., 2004; Pavlish et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2008; Tirodkar et al., 2010; Ypinazar & Margolis, 2006). This resonance of health beliefs across multiple segments within the American Muslim population, and from the diverse groups within our sample, substantiates a need to better understand the linkages between religious beliefs and practices and health care expectations. Furthermore, it illustrates the potential of culturally tailored interventions being portable to different segments of the American Muslim community.

The respondents also commented on several challenges for and unmet expectations from the human agents in healing. Echoing findings from other researchers, imams fulfill important psychological counseling roles within the community, and are at times used in lieu of trained mental health professionals (Abu-Ras et al., 2008; Ali, Milstein, & Marzuk, 2005). However, most imams currently have limited education in formal counseling, and it is unclear if they appropriately recognize when to refer to trained professionals, or have established connections with such resources. Therefore, collaborations between imams and mental health providers are important to establish so as to facilitate cultural understanding on the part of health care providers and impart counseling skills to imams.

Moreover, the participants expressed the desire to have greater imam representation within hospitals to meet Muslim patients' spiritual needs, and as resources for cultural competence training. Reasons for the sparse presence of imams in hospitals are multiple; imams might not have the time to devote to hospital activities and might be uncomfortable taking on a chaplaincy role because of their limited medical knowledge (Abu-Ras & Laird, 2010; Dudhwala, n.d.). From the health care system perspective, aside from a potential lack of fiscal resources, hospitals might not see a need for imams to be on staff because employed chaplains are expected to minister to patients from various religious backgrounds. Yet, pastoral care and chaplaincy training programs rarely include education on Islam, and it is uncertain if non-Muslim chaplains are morally comfortable counseling about a different religion (Abu-Ras & Laird; Hamza, 2007). Furthermore, it is unclear how well multifaith chaplains meet the spiritual needs of patients with religious backgrounds different than their own. Thus, non-Muslim hospital chaplains might not adequately fulfill the needs of Muslim patients, and because there are only a few Islamic chaplaincy programs in the United States, imams from the community can be an important resource to utilize within hospitals to meet patient needs (Dudhwala, 2008).

Given that allopathic health care providers are but one of multiple sources of healing for American Muslims, a strong patient–doctor alliance is of great importance. Some of the participants lamented that physicians sometimes did not accommodate their religious and cultural needs, and voiced concerns about their distant communication styles. Such deficiencies in the patient–doctor relationship have important implications for health care utilization and health care quality. Patient–provider communication difficulties, mistrust, and perceived discrimination all play parts in minority health care disparities and contribute to a poorer quality of care in general (Saha et al., 2008; Williams & Mohammed, 2009; Williams, 2007). Furthermore, poor patient–provider dynamics influence patient nonadherence with allopathic medicine, nondisclosure of alternative medicines, and delays in health-care-seeking (Chao, Wade, Kronenberg, Kalmuss, & Cushman, 2008 [AU Q: 4]; Lee & Lin, 2008).

Thus, our findings suggest that there is a continuing need to improve cross-cultural communication skills and enhance cultural sensitivity within the health care provider population serving American Muslims. American Muslims who find their physicians unaccommodating of their religious and cultural traditions, or not meeting their needs in terms of communication and education, might rely more heavily on folk medicines and spiritual cures in lieu of allopathic treatment. Although this pattern has been suggested by other work within the American Muslim community, such behaviors are subject to debate within other communities, and more focused research endeavors to uncover associations are necessary (Astin, 1998; Barnes, Powell-Griner, McFann, & Nahin, 2004; Chao et al., 2006; Kronenberg, Cushman, Wade, Kalmuss, & Chao, 2006; Padela et al., 2010)

It bears mention that we found a variety of healing patterns within our focus groups. Some participants held religious cures as primary, using allopathic medicines as secondary sources of healing, whereas others used them as integrative choices. Additional work is needed to explore the linkages between patient–doctor relationships and the utilization of alternative and spiritual therapies within the American Muslim community.

Moving from agents in healing to the conceptual model, our project has several significant implications for American Muslim community health. By mapping out the major actors in healing—God, imams, family members, health care providers, and friends and the community—we identify points of health care intervention to enhance community health. Given the God-centric view of healing, partnering with imams can allow for the dissemination of positive health care messages within a religious framework. Data from outside of the United States suggest that imams and mosques have the ability to improve health. For example, education of imams about tuberculosis resulted in mosque sermons leading to increased detection and treatment in Bangladesh (Rifat et al., 2008). In Afghanistan, similar outreach with imams was aimed at promoting reproductive planning to reduce maternal death rates, and in Britain, the British Heart Foundation regularly engages imams to deliver health-awareness-based sermons during Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting (Mason, 2010; Zaidi, 2006). Secondarily, given the possible patient–provider relationship difficulties noted above, imams might be able to help traverse the gap and reinforce allopathic health care as one of the means through which healing is achieved.

Given the significance of one's family and one's community and friends in healing for these American Muslims, there are also promising opportunities for strengthening social support mechanisms to promote health and healing. Family and other social support strongly influence the effectiveness of disease management programs in other family-centric ethnic communities such as Latinos in the United States, and efforts to effectively mobilize family and other social support are associated with improved management of diabetes, heart failure, and other chronic diseases (Gallant, 2003; Piette et al., 2008; Rosland, Heisler, Choi, Silveira, & Piette, 2010). Similar approaches might yield success within the American Muslim community. In addition to the importance of family in healing, in general, Muslim communities prefer the presence of family members in clinic and hospital settings, and might use familial health care decision-making processes. Many authors have commented on the need to accommodate this preference within an allopathic care model, and our findings further bolster this message (Fakhr El-Islam, 2008; Moazam, 2000; Sheets & el-Azhary, 1998).

To our knowledge, our work is the first that illustrates the major agents and their roles in healing as viewed by an extended American Muslim community. Using a community-based approach to recruitment, sampling from multiple segments of the American Muslim community, allowing for the language used within focus groups to be based on participant preference, and a qualitative research design lend strength and richness to our findings. At the same time, there are some clear limitations. Even though our data legitimately represent the voices of the southeast Michigan Muslim community, these are views of one community. The southeast Michigan Muslim community is notable in that it is large and well established, with some subgroups tracing their history in the United States across several generations (Hassoun, 2005). Ethnic density and social capital have protective health effects, and thus, there might be additional actors that our focus groups did not identify, and other significant issues and roles that might not have been captured (Halpern & Nazroo, 1999; Pickett & Wilkinson, 2008). Hence, sampling frames from different American Muslim communities, particularly those that are smaller and have fewer resources, might provide additional insight.

Furthermore, using a mosque-based recruitment strategy introduces selection bias toward those members of the Muslim American community who have a stronger or more formal religious framework; hence, our findings suggest the need for further empirical and normative research, and should not be assumed to be generalizable to all American Muslims. Given that we sought to uncover the influences of religion on health and health challenges, our sampling occurred through mosques. We felt mosques provided a first cut for identification with Islam and for religiosity. Developing and validating Islam-based measures of religiosity is integral to exploring associations between religion and health behaviors, and these efforts are still in the preliminary stages (Amer & Hood, 2008). Thus, next steps should include gaining views from multiple Muslim communities and from Muslims with varying levels of religious adherence to gauge the generalizability of our findings to these groups.

Another challenge to studying American Muslim health lies in the lack of accurate population statistics and capture of religious affiliation within national databases, which affect sampling frames and strategies for Muslim Americans. Thus, quantification of mechanistic relations between Islam, health practices and behaviors, and population health requires a concerted, systematic, sustained engagement on multiple levels involving community, state, and national actors. Our work thus represents a critical first step in setting such research agendas with several testable hypotheses; specifically, exploring the associations between specific healing practices, utilization patterns within the allopathic and community agents in healing, and religiosity merits further investigation.

In summary, the participants described several ways in which Islam influenced their views of actors in the healing process. First, that healing as well as illness and health are grants from God. The healing process takes place by seeking the assistance of the Divine through supplication and scripture-based cures and through human actors including imams, health care practitioners, family, and one's community and friends. Each human agent plays several key roles in this process affecting spiritual, psychological, and physical health. Several challenges were noted for these actors. Ameliorating the challenges faced by these actors and incorporating them as partners in improving health has the potential to improve American Muslim community health.

Acknowledgments

We thank the respondents for sharing their time and insight with us, as well as the community partners and steering committee members for their invaluable recruitment assistance and support: Muzammil Ahmed MD, Hamada Hamid DO MPH from the Institute for Social Policy & Understanding, Najah Bazzy RN from the Islamic Center of America, Adnan Hammad PhD from the Arab Community Center for Economic & Social Services, Mouhib Ayyas MD from the Islamic Shura Council of Michigan, and Ghalib Begg from the Council of Islamic Organizations of Michigan. We also thank Sonia Duffy RN and Michael D. Fetters MD MPH MA for assistance with study design, qualitative methods, and intellectual support. We also thank our research assistants for their assistance with data collection: Afrah Raza, Shoaib Rasheed, Ali Beydoun, Nadia Samaha, David Krass, and Samia Arshad MPH. [AU Q: 5]

Funding The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project and the time effort of authors Padela, Killawi, and DeMonner were supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. Additional project funding was provided by the Institute for Social Policy & Understanding. [AU Q: 7]

Biographies

Aasim I. Padela, MD, MS, is an emergency medicine physician and researcher in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program in the Departments of Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Amal Killawi, MSW, is a research assistant at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Jane Forman, ScD, MHS, is a research scientist at the Veteran Affairs Center for Practice Management and Outcomes Research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Sonya DeMonner, MPH, is a research associate at the Robert Woods Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and the Veteran Affairs Center for Practice Management and Outcomes Research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Michele Heisler, MD, MPA, is an associate professor at the Department of Internal Medicine and Health Behavior & Health Education, and a research scientist at the Veteran Affairs Health Services Research & Development Center of Excellence at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. [AU Q: 6]

References

- Abu-Ras W, Gheith A, Cournos F. The imam's role in mental health promotion: A study of 22 mosques in New York City's Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2008;3:155–176. doi:10.1080/15564900802487576. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ras W, Laird L. How Muslim and non-Muslim chaplains serve Muslim patients? [AU Q: 8] Does the interfaith chaplaincy model have room for Muslims' experiences? Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;50(1):46–61. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9357-4. doi:10.1007/s10943-010-9357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali OM, Milstein G, Marzuk PM. The imam's role in meeting the counseling needs of Muslim communities in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(2):202–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.202. Retrieved from http://psychservices.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/56/2/202[AU Q: 9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allied Media Corp. Muslims American demographic facts. n.d. Retrieved from http://www.allied-media.com/AM/[AU Q: 10]

- Amer MM, Hood RW., Jr Special issue: Part II. Islamic religiosity: Measures and mental health. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2008;3(1):1–5. doi:10.1080/15564900802156544. [Google Scholar]

- Arab American Institute Foundation Michigan. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.aaiusa.org/page/file/f6bf1bfae54f0224af_3dtmvyj4h.pdf/MIdemographics.pdf[AU Q: 11]

- Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(19):1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Advance Data. 2004;343:1–19. [AU Q: 12] doi:10.1016/j.sigm.2004.07.003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba-Yunus I. Muslims of Illinois—A demographic report. East-West University; Chicago: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio, et al. Cultural competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [AU Q: 13] Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad343.pdf[AU Q: 14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beine K, Fullerton J, Palinkas L, Anders B. Conceptions of prenatal care among Somali women in San Diego. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1995;40(4):376–381. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(95)00024-e. doi:10.1016/0091-2182(95)00024-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennstam A, Strandmark M, Diwan V. Perception of tuberculosis in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Wali ya nkumu in the Mai Ndombe district. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:299–312. doi: 10.1177/1049732303261822. doi:10.1177/1049732303261822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MT, Wade C, Kronenberg F. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine to conventional medical providers: Variation by race/ethnicity and type of CAM. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100(11):1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31514-5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709648/[AU Q: 15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MT, Wade C, Kronenberg F, Kalmuss D, Cushman LF. Women's reasons for complementary and alternative medicine use: Racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(8):719–720. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.719. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShaw P. Use of the emergency department by Somali immigrants and refugees. Minnesota Medicine. 2006;89(8):42–45. Retrieved from http://www.minnesotamedicine.com/PastIssues/PastIssues2006/August2006/ClinicalAugust2006/tabid/2784/Default.aspx[AU Q: 16] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries R, Berlinger N, Cadge W. Lost in translation: The chaplain's role in health care. Hastings Center Report. 2008;38(6):23–27. doi: 10.1353/hcr.0.0081. doi:10.1353/hcr.0.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhwala IY. Building bridges between theology and pastoral care. n.d. Retrieved from http://www.eurochaplains.org/060518_theology_yunus.pdf[AU Q: 17]

- Dudhwala IY. The growth of Muslim chaplaincy in the UK. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.plainviews.org/AR/c/v5n13/a.html[AU Q: 18]

- Fakhr El-Islam M. Arab culture and mental health care. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(4):671–682. doi: 10.1177/1363461508100788. doi:10.1177/1363461508100788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara S, Lopes AA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Kurokawa K, Mapes DL, Akizawa T, et al. Health-related quality of life among dialysis patients on three continents: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney International. 2003;64(5):1903–1910. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00289.x. [AU Q: 19] doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. doi:10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern D, Nazroo J. The ethnic density effect: Results from a national community survey of England and Wales. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1999;46(1):34–46. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600105. doi:10.1177/002076400004600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza DR. Faith-based practice on models of hospital chaplaincies: Which once works best for the Muslim community? Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2007;2:65–79. doi:10.1080/15564900701238591. [Google Scholar]

- Hartog J, Hartog EA. Cultural aspects of health and illness behavior in hospitals. Western Journal of Medicine. 1983;139(6):910–916. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1011024/[AU Q: 20] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun R. Arab Americans in Michigan. Michigan State University Press; East Lansing: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Healy-Ogden MJ, Austin W. Uncovering the lived experience of well-being. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:85–96. doi: 10.1177/1049732310379113. doi:10.1177/1049732310379113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, McClure SM. Perceptions of the religion-health connection among African American church members. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:268–281. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275634. doi:10.1177/1049732305275634 [AU Q: 21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Speaking of health: Assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . The future of the public's health in the 21st Century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Satcher D. Methods in community-based participatory research in health. Josey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jan R, Smith CA. Staying healthy in immigrant Pakistani families living in the United States. Image—The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1998;30(2):157–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01272.x. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Balneaves LG, Grewal S, Bhagat R, Hilton BA, Clarke H. South Asian womens' views on the causes of breast cancer: Images and explanations. Patient Education & Counseling. 1999;37(3):243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00118-9. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738399198001189[AU Q: 22] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Annal of Internal Medicine. 1978;88(2):251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. Retrieved from http://www.annals.org/content/88/2/251.abstract[AU Q: 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004;25:439–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg F, Cushman LF, Wade CM, Kalmuss D, Chao MT. Race/ethnicity and women's use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: Results of a national survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(7):1236–1242. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047688. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.047688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YY, Lin JL. Linking patients' trust in physicians to health outcomes. British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London) 2008;69(1):42–46. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2008.69.1.28040. Retrieved from http://www.bjhm.co.uk/cgibin/go.pl/library/abstract.html?uid=28040[AU Q: 24] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T, Straub M. “My head is like a bag full of rubbish”: Concepts of illness and treatment expectations in traumatized migrants. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:233–248. doi: 10.1177/1049732310383867. doi:10.1177/1049732310383867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malat J, van Ryn M. African-American preference for same-race health care providers: The role of health care discrimination. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15(4):740–747. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16259502[AU Q: 25] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. USA Today. Associated Press; Mar, 2010. Mullahs help promote birth control in Afghanistan. [AU Q: 26] Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-03-04-afghanistan-births_N.htm[AU Q: 27] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley WJ, Pecchioni L, Grant JA. Personal accounts of the role of God in health and illness among older rural African American and White residents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2000;15(1):13–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1006745709687. doi:10.1023/A:1006745709687 [AU Q: 28] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milat AJ, Carroll TE, Taylor JJ. Culturally and linguistically diverse population health social marketing campaigns in Australia: A consideration of evidence and related evaluation issues. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2005;16(1):20–25. doi: 10.1071/he05020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazam F. Families, patients, and physicians in medical decision making: A Pakistani perspective. Hastings Center Report. 2000;30(6):28–37. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11475993[AU Q: 29] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Morioka-Douglas N, Sacks T, Yeo G. Issues in caring for Afghan American elders: Insights from literature and a focus group. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2004;19(1):27–40. doi: 10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015015.63501.db. doi:10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015015.63501.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehra A, Kulaksizoglu H. Global perspectives and controversies in the epidemiology of male erectile dysfunction. Current Opinion in Urology. 2002;12(6):493–496. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200211000-00009. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12409879[AU Q: 30] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Hoogvorst A, Konradsen F, Mudasser M, van der Hoek W. Causes of childhood diarrhea as perceived by mothers in the Punjab, Pakistan. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2003;34(2):343–351. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12971560[AU Q: 31] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan FH. The Muslim population in the United States: A brief statement. American Muslim Council; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Obama B. Remarks by the President on a new beginning. Speech presented at Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt; Jun, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-cairo-university-6-04-09[AU Q: 32] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow M. The ethics of cultural competence. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(4):347–350. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00012. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15044168[AU Q: 33] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padela AI, Killawi A, Heisler M, Demonner S, Fetters MD. The role of imams in American Muslim health: Perspectives of Muslim community leaders in southeast Michigan. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;50(2):359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9428-6. doi:10.1007/s10943-010-9428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlish CL, Noor S, Brandt J. Somali immigrant women and the American health care system: Discordant beliefs, divergent expectations, and silent worries. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(2):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett K, Wilkinson R. People like us: Ethnic group density effects on health. Ethnicity & Disease. 2008;13(4):321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. doi:10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Gregor MA, Share D, Heisler M, Bernstein SJ, Koelling T, Chan P. Improving heart failure self-management support by actively engaging out-of-home caregivers: Results of a feasibility study. Congestive Heart Failure. 2008;14:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.07474.x. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.07474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 8) [Computer software] Author; Melbourne, Australia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram SS, Rashidi A. Asian-Islamic women and breast cancer screening: A socio-cultural analysis. Women Health. 1999;28(3):45–58. doi: 10.1300/J013v28n03_04. [AU Q: 34] doi:10.1300/J013v28n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifat M, Rusen ID, Mahmud MH, Nayer I, Islam A, Ahmed F. From mosques to classrooms: Mobilizing the community to enhance case detection of tuberculosis. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(9):1550–1552. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117333. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18633095[AU Q: 35] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi HJ, Silveira MJ, Piette JD. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illness. 2010;6(1):22–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608. doi:10.1177/1742395309354608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):654–671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SM, Ayash C, Pharaon NA, Gany FM. Arab American immigrants in New York: Health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2008;10(5):429–436. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9106-2. doi:10.1007/s10903-007-9106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets DL, el-Azhary RA. The Arab Muslim client: Implications for anesthesia. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. 1998;66(3):304–312. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9830857[AU Q: 36] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. The Muslim population of the United States: The methodology of estimates. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2002;66:404–417. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3078769[AU Q: 37] [Google Scholar]

- Tirodkar MA, Baker DW, Makoul GT, Khurana N, Paracha MW, Kandula NR. Explanatory models of health and disease among South Asian immigrants in Chicago. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;13(2):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9304-1. doi:10.1007/s10903-009-9304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RA. Eliminating health care disparities in America: Beyond the IOM report. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yehya NA, Dutta MJ. Health, religion, and meaning: A culture-centered study of Druze women. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20:845–858. doi: 10.1177/1049732310362400. doi:10.1177/1049732310362400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ypinazar VA, Margolis SA. Delivering culturally sensitive care: The perceptions of older Arabian Gulf Arabs concerning religion, health, and disease. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:773–787. doi: 10.1177/1049732306288469. doi:10.1177/1049732306288469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi Q. Breaking barriers: Health promotion initiatives in places of worship. Practical Cardiovascular Risk Management. 2006;4(3):8–10. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/source/sourceInfo.url?sourceId=3900148504[AU Q: 38] [Google Scholar]