Abstract

Severe crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis is typically associated with anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). In this report, we describe a 23-year old man with severe crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Both anti-GBM and ANCA titers were negative. Kidney biopsy showed bright C3 staining in the mesangium and along capillary walls and no staining for immunoglobulins. Electron microscopy showed waxy deposits (many mesangial; few intramembranous or subendothelial), prompting an evaluation of the alternative pathway of complement. alternative pathway evaluation revealed a novel mutation in short consensus repeat (SCR) 19 of complement factor H (CFH). In addition, the patient carried CFH and C3 risk alleles. Prompt treatment with intravenous steroids followed by oral steroids resulted in symptom alleviation and improved kidney function This case shows what is to our knowledge a unique and previously unpublished cause of severe crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Furthermore, the case demonstrates an expanding spectrum of complement-mediated glomerulonephritis and shows that crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis with solely complement deposits should be evaluated for abnormalities in the alternative pathway of complement.

Crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis (GN) is the most severe form of kidney injury. In the majority of cases the pathologic process is due to injury resulting from circulating anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies, immune complex deposition, or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). These forms of glomerulonephritis are often classified as type I, type II, and type III (pauci-immune crescentic GN), respectively.(1) Immune-complex mediated GN with crescents include entities such as lupus nephritis and IgA nephropathy.

In this manuscript we report the case of a patient with severe crescentic and necrotizing GN associated with a novel mutation in the complement factor H gene (CFH), a key component in the regulation of the alternative pathway of complement.(2) We discuss the implications of these findings and suggest evaluation of the alternative pathway in certain cases of crescentic and necrotizing GN.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year old previously healthy man presented with myalgias, loss of appetite, vomiting, fever and joint pains following extensive physical exertion. He noted that his urine was brownish-red. He denied a sore throat, skin rash or dysuria. He also had not experienced any chest pain, syncope, or hemoptysis. Initial examination revealed a fever of 99°F, blood pressure 130/75, pulse 76/minute, and respiration rate of 20/minute. Cardiovascular, lung, and neurological examinations were unremarkable. He was active as a player on a college football team, and used non-steroidal analgesic drugs (NSAIDs) prior to and after games. There was no family history of kidney disease. Initial laboratory evaluation showed a serum creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL (159.12 µmol/L) corresponding to an eGFR of 51 ml/min/1.73m2 (.85 mL/s/1.73m2) as determined using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation with no schistocytes on peripheral smear. Urinalysis was significant for hematuria. The laboratory data are shown in table 1. The clinical impression was that of acute tubular necrosis secondary to dehydration or rhabdomyolysis, acute interstitial nephritis due to NSAID use, and a post-infectious GN due to the active urinary sediment. A kidney biopsy was performed to determine the cause of the kidney failure and the active urinary sediment.

Table 1.

Laboratory evaluation

| Laboratory Results | Reference range |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| at presentation | After 6 mo | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5 | 13.3 | 14–18.0 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 55 | 10 | 0–22 |

| Platelets (×103/µl) | 275 | 309 | 150–400 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 13.1 | 9.7 | 3.5–10.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.5–4.8 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase (U/L) | 58 | 49–397 | |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 137 | 142 | 136–144 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.2 | 4.5 | 3.6–5.1 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 99 | 99–109 | |

| Carbon Dioxide (mEq/L) | 29 | 22–32 | |

| Serum urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 12 | 19 | 4–20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.6–1.2 |

| eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 51 | >60 | >60 |

| C3 complement (mg/mL) | 1.35 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.52 |

| C4 complement (mg/mL) | .37 | 0.31 | 0.16–0.38 |

| ASO titers (IU/mL) | 240 | 0–250 | |

| Hepatitis serology | Negative | ||

| Urinalysis | 50–100 RBC/HPF | 3–10 RBC/HPF | |

| Urinary protein (mg/24 h) | 800 | ||

| Blood and urine cultures | Negative | Negative | |

| Cryoglobulins | Undetectable | ||

| ANA, dsDNA | Undetectable | ||

| ANCA, PR3 and MPO | Undetectable | Undetectable | |

eGFR calculated using Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation

Note: Conversion factors for units: hemoglobin in g/dL to g/L, ×10; albumin in g/dL to g/L ×10; creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, ×88.4; eGFR in mL/min/1.73 m2 to mL/s/1.73 m2 ×0.01667. No conversion is necessary for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, platelets in ×103/µL and ×109/L, WBC in ×103/µL and ×109/L, sodium in mEq/L to mmol/L, potassium in mEq/L to mmol/L, chloride in mEq/L to mmol/L, carbon dioxide in mEq/L to mmol/L, C3complement in mg/mL to g/L, C4 complement in mg/mL to g/L.

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; PR3, proteinase 3; MPO, myeloperoxidase; RBC, red blood cell; HPF, high-power field; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA

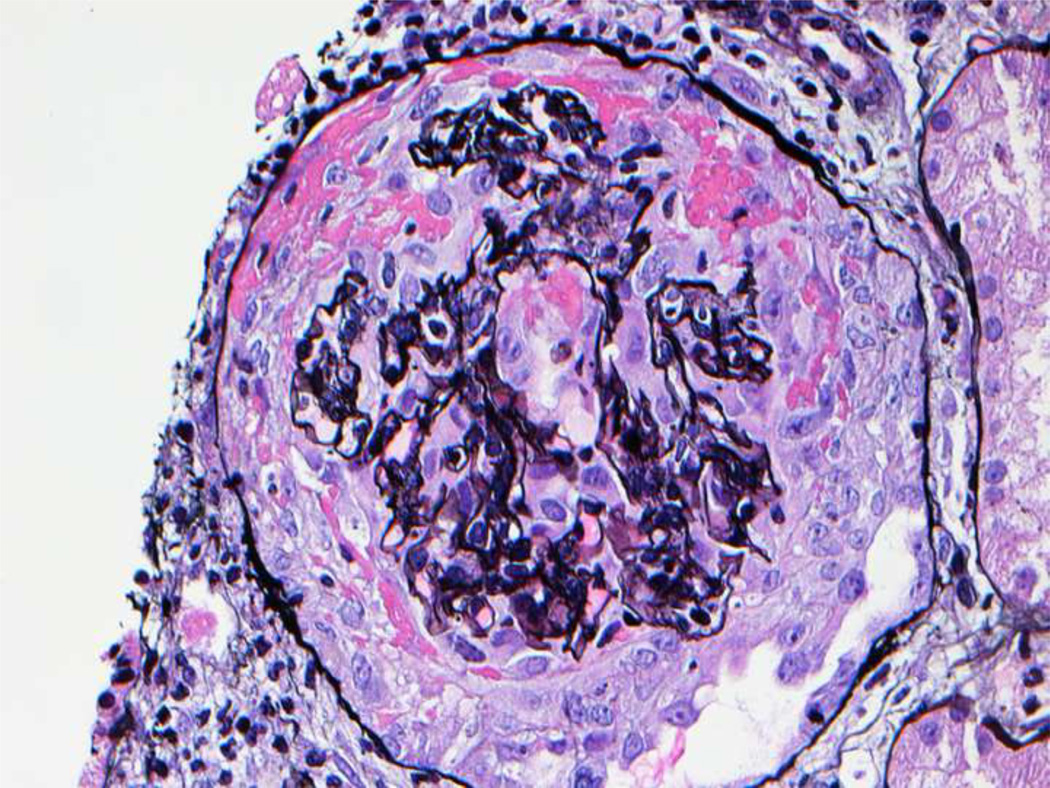

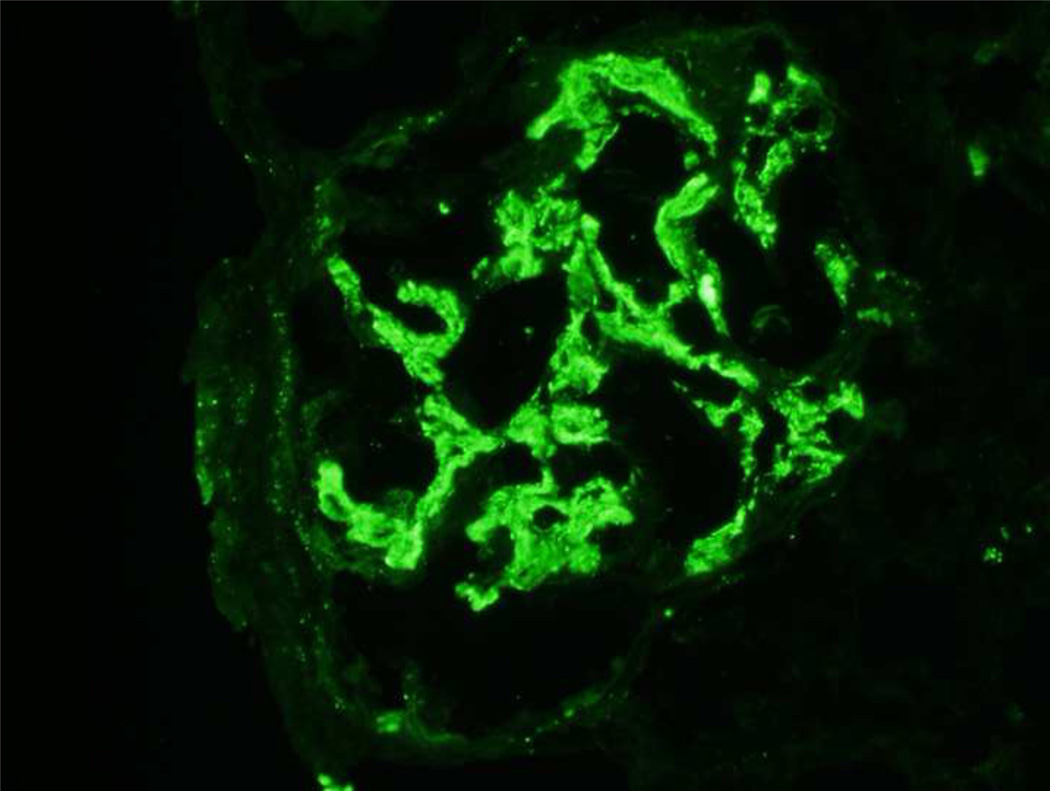

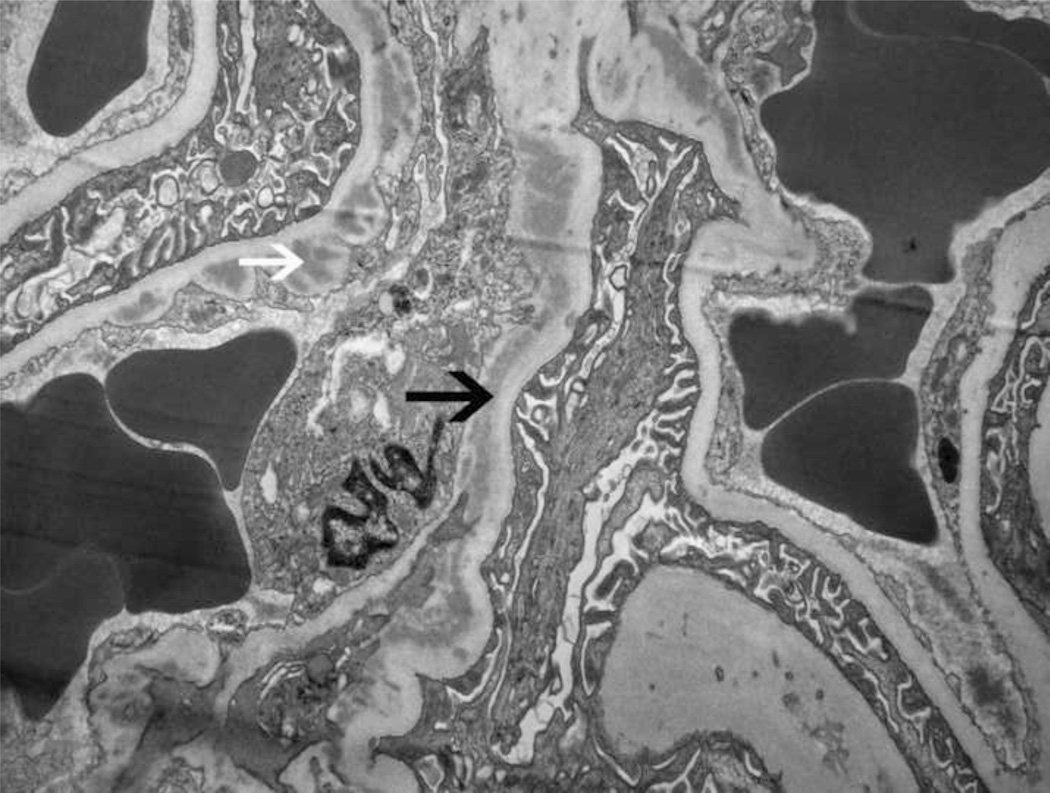

Twenty glomeruli were present for light microscopic evaluation, one of which was globally sclerosed. Two glomeruli showed segmental scars with adhesion of the scarred segments to the Bowman’s capsule. Nine of the remaining 17 glomeruli showed large circumferential cellular crescents (Figure 1A and B), with many areas of segmental fibrinoid necrosis (necrotizing lesions). Few intracapillary neutrophils were also noted, but most of the glomeruli not within the region of the crescents or necrosis appeared unremarkable and did not show any proliferative or exudative features. There was no interstitial inflammation present. Tubules contained RBCs and RBC casts. There was no significant tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis present. Vessels were unremarkable. Immunofluorescence studies revealed 7 glomeruli, one of which was globally sclerosed. The glomeruli showed bright granular 3+ mesangial and capillary wall staining for C3 (Figure 1C). In the glomeruli, IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, kappa and lambda light chains were undetectable. Electron microscopy revealed mesangial and paramesangial electron dense deposits (Figure 1E). A few subepithelial “hump-like” deposits (Figure 1F) and a few small subendothelial and intramembranous deposits were also present (Figure 1G). Sausage-shaped large electron dense deposits were not present along the glomerular basement membranes. Based on these findings, the initial kidney biopsy diagnosis was of a post-infectious GN, with crescents and necrosis.

Figure 1. Kidney biopsy findings.

(A) Low power view of 4 glomeruli, 3 with crescents and 1 unremarkable (Jones stain 10×). (B) High power image of a glomerulus with a large circumferential crescent and necrotizing lesion. Note absence of endocapillary proliferation, or mesangial or membranoproliferative features (Jones stain, 40×). Immunofluorescence studies reveal (C) bright 3+ staining for C3 in the mesangium and along capillary walls (40×), and (D) bright fibrinogen staining in the glomerular tufts indicating fibrinoid necrosis (necrotizing lesion). Electron microscopy reveals (E) mesangial and paramesangial deposits with a fuzzy/waxy character (black arrows point to deposits) (5800×); (F) a subepithelial hump (7400×); and (G) few subendothelial (white arrow) and intramembranous deposits (black arrow)(7400×).

A search for an infectious etiology found no indication of a triggering event of this nature. Multiple blood and urine cultures gave negative results. Anti-streptolysin O titers were not elevated. ANCA and anti-GBM titers were negative. Due to the severe crescentic and necrotizing lesions on the kidney biopsy, the patient was initially treated with bolus intravenous steroids for 3 days. He was then switched to oral prednisone and the dose was tapered down to 20 mg/day over 6 weeks. His serum creatinine returned to 1.2 mg/dL (106.08 µmol/L) corresponding to an eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (> 1 mL/s/1.73 m2). However, when the prednisone was stopped the symptoms, including back pain, returned and the patient started feeling worse. The serum creatinine started to rise again and urinalysis showed hematuria. The patient was restarted on oral prednisone. He also developed hypertension for which he was started on amlodipine. At this time he was referred to the Mayo Clinic.

A review of the biopsy showed some features that were atypical for postinfectious GN, but instead were suggestive of a unique and severe crescentic and necrotizing GN resulting from an abnormality in the alternate pathway of complement (alternative pathway).(3) These included the following: 1) Many glomeruli did not show endocapillary proliferation or mesangial proliferation; 2) Immunofluorescence studies showed bright 3+ staining for C3 in the mesangium and along capillary walls and the absence of immunoglobulin staining; and 3) Many mesangial and paramesangial deposits, few subendothelial and subepithelial deposits, and few waxy intramembranous deposits were noted on electron microscopy. In our experience, the strong 3+ staining for C3, absence of immunoglobulin staining, intramembranous and occasional subepithelial deposits are good markers for GN resulting from dysregulation of the alternative pathway. Thus, the alternative pathway was evaluated and this led to rather surprising results.

Direct sequence analysis of the coding region of CFH including analysis of intron/exon boundaries revealed a heterozygous single-nucleotide polymorphism, a guanine to adenine change at nucleotide 3,350 of the CFH complementary DNA (c.3350A>G; corresponding to an asparagine to serine change at amino acid 1,117 [p.Asn1117Ser]), which occurs in short consensus repeat (SCR) 19 (figure 2). This substitution has, to our knowledge, not been previously described. The consequence score is 5 exposed (1, low; 9, high) and PolyPhen, a tool that predicts the potential effects of an amino acid substitution on a protein of interest (available at genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/), suggests that this change is possibly damaging. In addition, risk alleles that were identified included 2 copies of the CFH risk polymorphism H402 (reference single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs) number 1061170; corresponding to a tyrosine to histidine change at amino acid 402 in SCR7), two copies of the C3 risk allele G102 (an arginine to glycine substitution at amino acid 102), and 1 copy of the C3 risk allele L314 (a proline to leucine substitution at amino acid 314). The CFH risk allele I62 (rs800292), by contrast, was not present. Moreover, sequence analysis of the genes for complement factors B (CFB) and I (CFI), membrane cofactor protein (CD46), CFHrelated protein 5 (CFHR5), and the CFHR3-CFHR1 region (by multiplex ligationdependent probe amplification) revealed the patient was homozyogous for the wild-type alleles. Antibodies to complement regulating proteins, including C3 nephritic factor (C3NeF), CFH, and CFB, were also undetectable (table 2).

Figure 2. Schematic of complement factor H (CFH) and relevant mutations.

CFH contains 20 short consensus repeats (SCRs; indicated by circles). SCR19, the location of the polymorphism described in this case, is shown with an arrow. Dark blue circles represent C3b binding sites (SCR 1–4, SCR 7–15, SCR 19–20). Mutations in SCR1–4 are usually associated with dense deposit disease/C3 glomerulonephritis (DDD/C3 GN), while mutations in SCR 19–20 are associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). Some cases of DDD/C3 GN have also reported in association with mutations in SCR 7–15.

Table 2.

Characterization of the alternative pathway via functional assays and antibody detection analysis

| Complement Test | Result | Criteria for Negative/Normal Result |

|---|---|---|

| CFH Autoantibody | negative | Titer <1:50 |

| Hemolytic Assay | Normal, no hemolysis detected | <3% hemolysis |

| Alternative Pathway Functional Assay | 79.86% | Within reference range of 65%–130% |

| C3 Nephritic Factor | ||

| ELISA | negative | OD < 2 SD above normal based on 50 healthy controls |

| Immunofixation electrophoresis | negative | <7.5% |

| C3 convertase stabilizing assay | negative | <20% |

| C3 convertase stabilizing assay with properdin | negative | <20% |

Abbreviations: CFH, complement factor H; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OD, optical density; SD, standard deviation

We performed laser microdissection and mass spectrometry to determine the glomerular proteomic profile. (4) There was extensive deposition of fibrinogen α, fibrinogen β, and fibrinogen γ, consistent with crescentic and necrotizing GN. There was also deposition of C3 and CFHR1, and less intense spectra corresponding to proteins identified with lower confidence as C9 and CFHR5 (figure 3). There was no evidence suggesting accumulation of complement factors of the classical complement pathway, such as C1, C2 or C4. In addition, there was no immunoglobulin present.

Figure 3. Laser microdissection and mass spectrometry.

(A) glomeruli marked for microdissection. (B) The top 19 proteins detected by mass spectrometry. The proteomic data show accumulation of fibrinogen α, β, and γ, C3, and CFHR1 (yellow-starred records) based on >95% probability of a positive match of mass spectrometric data with protein databases. Lower-probably matches were seen for C9 and CFHR5.

As a result of these additional investigations, the diagnosis was refined to crescentic and necrotizing GN, severe, associated with dysregulation of the alternative pathway of complement resulting from a mutation and a permissive background in CFH and C3.

At time of writing, one year after initial presentation, the patient is well and asymptomatic. His serum creatinine is stable at 1.2 mg/dL (eGFR > 60 ml/minute) and he has been maintained on prednisone (15 mg/day) for the last 6 months. Attempts to reduce the dosage have resulted in a return of symptoms.

Discussion

We report a case of young man with a severe crescentic and necrotizing GN associated with a novel mutation in CFH, the most important regulator of the alternative complement pathway. Mutations in CFH result in dysregulation and uncontrolled activation of the alternative pathway, causing deposition of activated complement factors and complement degradation products in the glomeruli, ultimately leading to proliferative GN.(2) Based on electron microscopy, such lesions are classified as either Dense Deposit Disease (DDD) or C3 GN. (3, 5, 6) In both DDD and C3 GN, the underlying lesion is typically one of a proliferative GN, such as mesangial, endocapillary, or membranoproliferative GN. Crescents and necrotizing lesions can also be present, but the predominant lesion is that of a proliferative GN.(7, 8) Our case was extremely unusual in that the kidney biopsy showed a severe crescentic and necrotizing GN with no significant mesangial or membranoproliferative features. It is likely that the lesion developed acutely with no time for progression and development of mesangial or membranoproliferative features. Treatment with intravenous high-dose steroids followed by oral low-dose steroids for maintenance controlled the disease process by both alleviating symptoms and improving kidney function.

Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed bright C3 staining in the mesangium and along capillary walls and complete absence of Ig staining. In addition, small waxy intramembranous, subendothelial, and subepithelial deposits suggested complement deposits (as opposed to Ig-containing deposits, which appear darker and more sharply demarcated). These findings prompted assessment of the alternative pathway, which to our surprise revealed a polymorphism in the sequence corresponding to SCR19 of CFH (Figure 2), an extremely unusual finding in the setting of crescentic and necrotizing GN since mutations in SCR19 have not been previously described to cause C3 GN or DDD. Evaluation also revealed 2 copies of the H402 allele of CFH, and in C3, 2 copies of the G102 allele and 1 copy of the L314 allele. These variants of CFH and C3 are causally associated with increased baseline alternative pathway activity even in healthy controls and are linked to both C3 GN and DDD.(9–11)

CFH has 20 SCRs, each of which is about 60 amino acids long. SCRs 1–4 are at the amino terminus, bind C3b, and are important for fluid-phase regulation of the C3 convertase. Mutations in these domains have been reported in DDD and C3 GN. (5, 6) SCRs 19–20 at the carboxy terminus are essential for CFH binding to host surfaces, and also interact with the C3b degradation products iC3b and C3d.(12) The importance of these two SCRs has been verified in experiments using a recombinant protein containing only SCR 19–20 of CFH; this truncated protein competes with full-length CFH for C3b binding sites and host polyanions, resulting in complement activation on host surfaces in vitro. (13) Mutations in SCR19–20 are causally associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) (14, 15) but have not been reported in the setting of a crescentic and necrotizing GN. Thus, this case demonstrates a new pattern/manifestation of severe injury, i.e., crescentic and necrotizing GN, associated with a polymorphism in SCR19 of CFH and, we suggest, a permissive environment resulting from the presence of the H402 variant of CFH and the G102 and L314 variants of C3.

Severe crescentic and necrotizing GN in the absence of significant mesangial or membranoproliferative features is typically seen in anti-glomerular basement membrane GN and ANCA-associated pauci-immune GN. At the same time, severe crescentic and necrotizing GN due to a CFH mutation has not been reported. To our knowledge this is the first case to link a severe crescentic and necrotizing GN to a CFH mutation. This also expands the spectrum of kidney lesions that occur due to abnormalities of the alternative pathway. Although this case could fall under the umbrella of C3 glomerulopathy and C3 GN (given the bright C3 staining on immunofluorescence studies and mesangial and capillary wall deposits on electron microscopy), the morphologic pattern of severe injury, i.e., crescentic and necrotizing GN, is extremely unusual. Laser microdissection–mass spectrometry data was consistent with a necrotizing GN associated with complement deposition because large signals corresponding to fibrinogen and C3 were noted in the glomeruli along with the absence of any detectable immunoglobulin deposition (figure 3).

It is possible that some cases currently labeled as pauci-immune crescentic and necrotizing GN may be a result of alternative pathway dysfunction, particularly those belonging to the 15% that are ANCA-negative. The finding of glomerular C3 staining (in the absence of Ig staining) is sometimes dismissed as non-specific in the setting of a pauci-immune crescentic and necrotizing GN. Based on the case described in this report, we postulate that some of these cases may be associated with alternative pathway dysfunction.

Finally, this case is noteworthy because aHUS, DDD, and C3 GN are all complement-mediated diseases. The p.Asn1117Ser mutation were described herein lies in SCR19, a commonly mutated SCR in aHUS (Figure 2), but the resulting phenotype in this case was severe crescentic and necrotizing GN and not aHUS, suggesting that other modifying genetic changes may be present in this person. Distinguishing DDD and C3 GN at the genetic and biomarker levels is more challenging, but again, this case offers some insights. Fluid-phase dysregulation of the C3 convertase alone is sufficient to result in DDD as Martínez-Barricarte and colleagues demonstrated in a small nuclear family in which a mother and her two identical twin boys segregated a two amino-acid deletion in the MG7 domain of C3 (the loss of the aspartate and glycine residues at amino acids 923 and 924, respectively).(16) The association of severe crescentic and necrotizing GN with a polymorphism in SCR19 of CFH suggests that dysregulation of the C5 convertase may also be important in some cases of complement-mediated GN.(17)

To summarize we present a case of severe crescentic and necrotizing GN associated with a novel mutation in CFH and the presence of 2 copies of the H402 allele of CFH and 2 copies of the G102 and 1 copy of the L314 alleles of C3. A crescentic and necrotizing GN with extensive glomerular C3 staining on immunofluorescence studies warrants an in depth evaluation of the alternative pathway.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julie A. Vrana and Jason D. Theis for their help with laser microdissection and mass spectrometry.

Support: This research was supported in part by NIH grant DK074409 to Dr. Sethi and Dr. Smith, and Fulk Family Foundation award (Mayo Clinic) to Dr. Sethi

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Jennette JC, Olson LJ, Schwartz MM, Silva GF. Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney. 6th Edition edn. Wolters Kluwer and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 255–319. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipfel PF, Skerka C. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nri2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethi S, Fervenza FC, Zhang Y, Nasr SH, et al. Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Secondary to Dysfunction of the Alternative Pathway of Complement. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;6:1009–1017. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07110810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethi S, Gamez JD, Vrana JA, Theis JD, et al. Glomeruli of Dense Deposit Disease contain components of the alternative and terminal complement pathway. Kidney Int. 2009;75:952–960. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RJH, Alexander J, Barlow PN, Botto M, et al. New Approaches to the Treatment of Dense Deposit Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18:2447–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servais A, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Lequintrec M, Salomon R, et al. Primary glomerulonephritis with isolated C3 deposits: a new entity which shares common genetic risk factors with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007;44:193–199. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker PD, Ferrario F, Joh K, Bonsib SM. Dense deposit disease is not a membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:605–616. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leroy V, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Peuchmaur M, Baudouin V, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with C3NeF and genetic complement dysregulation. Pediatric Nephrology. 2011;26:419–424. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrera-Abeleda MA, Nishimura C, Smith JLH, Sethi S, et al. Variations in the Complement Regulatory Genes Factor H (CFH) and Factor H Related 5 (CFHR5) are Associated with Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis Type II (Dense Deposit Disease) J Med Genet. 2006;43:582–589. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.038315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrera-Abeleda MA, Nishimura C, Frees K, Jones M, et al. Allelic Variants of Complement Genes Associated with Dense Deposit Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;22:1551–1559. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Meyer NC, Wang K, Nishimura C, et al. Causes of Alternative Pathway Dysregulation in Dense Deposit Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012 doi: 10.2215/CJN.07900811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jokiranta TS, Hellwage J, Koistinen V, Zipfel PF, et al. Each of the Three Binding Sites on Complement Factor H Interacts with a Distinct Site on C3b. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:27657–27662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK, Cortés C. Complement control protein factor H: The good, the bad, the inadequate. Molecular Immunology. 2010;47:2187–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehtinen MJ, Rops AL, Isenman DE, van der Vlag J, et al. Mutations of Factor H Impair Regulation of Surface-bound C3b by Three Mechanisms in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:15650–15658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jokiranta TS, Jaakola V-P, Lehtinen MJ, Parepalo M, et al. Structure of complement factor H carboxyl-terminus reveals molecular basis of atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome. EMBO J. 2006;25:1784–1794. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Barricarte R, Heurich M, Valdes-Cañedo F, Vazquez-Martul E, et al. Human C3 mutation reveals a mechanism of dense deposit disease pathogenesis and provides insights into complement activation and regulation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:3702–3712. doi: 10.1172/JCI43343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sethi S, Nester CM, Smith RJH. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and C3 glomerulopathy: resolving the confusion. Kidney Int. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]