Abstract

Aging is associated with oxidative stress and heightened inflammatory response to infection. Dietary interventions to reduce these changes are therefore desirable. Broccoli contains glucoraphanin, which is converted to sulforaphane (SFN) by plant myrosinase during cooking preparation or digestion. SFN increases antioxidant enzymes including NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) and heme oxygenase I (HMOX1) and inhibits inflammatory cytokines. We hypothesized that dietary broccoli would support an antioxidant response in brain and periphery of aged mice and inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and sickness. Young adult and aged mice were fed control or 10% broccoli diet for 28 days prior to an intraperitoneal LPS injection. Social interactions were assessed 2, 4, 8, and 24 h following LPS, and mRNA quantified in liver and brain at 24 h. Dietary broccoli did not ameliorate LPS-induced decrease in social interactions in young or aged mice. Interleukin (IL)-1β expression was unaffected by broccoli consumption but was induced by LPS in brain and liver of adult and aged mice. Additionally, IL-1β was elevated in brain of aged mice without LPS. Broccoli consumption decreased age-elevated cytochrome b-245 β, an oxidative stress marker, and reduced glial activation markers in aged mice. Collectively, these data suggest that 10% broccoli diet provides a modest reduction in age-related oxidative stress and glial reactivity, but is insufficient to inhibit LPS-induced inflammation. Thus, it is likely that SFN would need to be provided in supplement form to control the inflammatory response to LPS.

Keywords: Aging, BALB/c mice, broccoli, inflammation, LPS, sulforaphane

1. Introduction

Aging is accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation and increased oxidative stress, both of which are common factors in the pathology of chronic diseases [1,2]. Chronic inflammation leads to cognitive deficits and increases likelihood of developing neurodegenerative disease [3]. The aging brain is highly sensitive to inflammatory mediators generated in the periphery, evidenced by the molecular and behavioral changes that follow a peripheral immune stimulus such as infection, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin, or stress [4–6]. In fact, LPS-challenged aged mice exhibit exacerbated inflammation in the brain compared to adult mice [6,7]. Exaggerated expression of inflammatory mediators associated with immune activation in the aged signifies a need to identify interventions that attenuate age-related inflammation and oxidative stress both centrally and peripherally.

The nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is the primary transcriptional regulator of the cellular antioxidant response and is increasingly implicated in longevity and protection from inflammation. Declining Nrf2 activity may also be involved in the deleterious neurocognitive decline associated with aging [8–10]. The broccoli-derived bioactive sulforaphane (SFN) elicits activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway, which protects tissues from toxic and carcinogenic insult by promoting transcription of genes containing the antioxidant response element (ARE) [11–13]. Due to the cytoprotective nature of Nrf2, activation of the Nrf2 pathway may be a good therapeutic target for reducing oxidative and immune stress associated with chronic low-grade inflammation. In addition to evoking a Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response, SFN also displays anti-inflammatory effects in vitro, which generates further interest in SFN and foods rich in SFN as potential therapeutic candidates for chronic inflammatory diseases [14,15]. As highlighted in a recent review article, the beneficial effects of sulforaphane have also been demonstrated in a number of experimental animal models, with evidence strongly suggesting that sulforaphane is a versatile treatment for inflammation and oxidative stress [16].

Significant advances have been made in understanding the biochemical mechanisms underlying SFN-mediated activation of Nrf2 and its physiological effects, but minimal research has examined whether whole broccoli consumption influences age-associated inflammation. Broccoli provides a rich dietary source of vitamins, minerals, and flavonoids, but the unique nature of its health-promoting benefits, including cancer prevention and increased endogenous antioxidant production, have been associated with its naturally high levels of glucoraphanin [17–19]. Glucoraphanin is enzymatically hydrolyzed to the bioactive isothiocyanate SFN during crushing, chewing, or digestion of broccoli. Frequent intake of broccoli is associated with lowered risk of cancer and elevation of antioxidant enzymes [20,21]. Therefore, clinical research involving dietary supplementation with broccoli has focused primarily on chemoprevention and detoxification through activation of Phase II enzymes. Despite the accumulating evidence that SFN reduces inflammatory markers in cell culture and protects against oxidative stress during brain injury in vivo, the effects of dietary broccoli on peripheral and central inflammation in adult and aged animals have not been thoroughly investigated. Our objective was to examine whether dietary broccoli reduces LPS-induced inflammatory markers in brain or liver of aged mice, and whether dietary broccoli could alter the sickness behavior response to LPS. We hypothesized that dietary broccoli would support an antioxidant response in brain and periphery of aged mice and inhibit LPS-induced inflammation and sickness behavior. In order to test this hypothesis, we used a pre-clinical murine model to investigate whether four weeks of dietary supplementation was sufficient to decrease markers of inflammation and reduce sickness behavior in adult and aged mice challenged with LPS. Sickness behavior and molecular inflammatory response has been well-characterized in our model of LPS-challenged aged mice, and these measurements will provide useful information for determining if broccoli supplementation attenuates behavioral complications of inflammation. A reduction in LPS-induced proinflammatory markers in the broccoli-supplemented mice would indicate that broccoli is a suitable dietary addition to temper inflammation.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1 Animals and experimental diets

Adult (4-month-old) and aged (18-month-old) BALB/c mice reared in-house were individually housed in a temperature controlled environment with a reversed phase light:dark cycle (lights on 8:00 pm). During the 28-day experimental period, mice were given ad libitum access to water and diet consisting of AIN-93M or AIN-93M + 10% freeze-dried broccoli (Table 1). Soy oil was replaced with corn oil to mitigate any potential anti-inflammatory effects derived from increased omega-3 fatty acid content of soy oil. The broccoli used in the diet provided 5.22 μmol SFN/g as determined by laboratory hydrolysis using the methods described by Dosz and Jeffery [22]. Therefore, it is estimated that mice fed the 10% broccoli diet were exposed to 0.5 μmol glucoraphanin per g of diet consumed, providing up to 0.5 μmol SFN/g, depending upon the extent of glucoraphanin hydrolysis. To diminish the potential for degradation of glucosinolates from the broccoli-containing diet, both diets were replaced every other day. Body weight (BW) was recorded weekly. Mice were handled 1–2 min per day for one week prior to behavior testing. All studies were carried out in accordance with United States National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table 1.

| AIN-93M | AIN-93M + 10% Broccoli | |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 14.7% | 14.7% |

| Carbohydrate | 75.9% | 75.9% |

| Fat | 9.4% | 9.4% |

| Freeze-dried broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. cv “Green Magic”) | -- | 100 g |

| Casein | 140 g | 113.6 g |

| Corn Starch | 495.7 g | 473.8 g |

| Maltodextrin 10 | 125 g | 110.1 g |

| Sucrose | 100 g | 99.1 g |

| Cellulose | 50 g | 25.7 g |

| L-Cystine | 1.8 g | 1.8 g |

| Mineral Mix | 35 g | 35 g |

| Vitamin Mix | 10 g | 10 g |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.5 g | 2.5 g |

| Corn oil | 40 g | 36.5 g |

Broccoli was grown at the University of Illinois, Urbana. All other diet ingredients were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN).

Nutrient content of broccoli was obtained from the USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference

2.2 Immune challenge

Escherichia coli LPS (serotype 0127:B8, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile saline prior to experimentation. On day 29 of dietary intervention, mice from each diet group (n = 7) were given LPS (0.33 mg/kg BW) or saline intraperitoneally (i.p.). Treatments were administered during the first hour after onset of the dark phase of the light:dark cycle.

2.3 Behavioral testing

To determine whether broccoli diet reduced sickness behavior, social exploratory behavior was assessed in all mice 2, 4, 8, and 24 h after treatment, as previously described in detail [23]. Base-line social exploratory behavior was determined 24 h prior to treatment and was used as a basis of comparison for calculating percent baseline time spent investigating a novel juvenile. A novel juvenile conspecific mouse was placed inside a protective cage before being placed in the home cage of the experimental mouse. Social interactions were video-recorded for 5 min and scored by an experimenter blinded to the treatments. Social exploration is determined as the amount of time spent investigating the juvenile (sniffing, in close proximity to the juvenile) and is reported as percent of baseline.

2.4 Tissue collection and analysis

Animals were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation 24 h after treatment, perfused with sterile ice-cold saline, then brain and liver tissues were dissected and flash frozen. All tissue samples were stored at −80°C until further processing for analysis.

RNA was isolated using E.Z.N.A. Total RNA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA). Synthesis of cDNA was carried out using a high capacity RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed to detect changes in mRNA expression of ARE genes NQO1 (Mm.PT.56a.9609207) and HMOX1 (Mm.PT.56a.9675808) and the transcription factor Nrf2 (Mm.PT.56a.29108649M). The inflammatory cytokine IL-1β (Mm.PT.56a.41616450) was used as a marker to detect if inflammatory cytokine production was reduced in animals fed the broccoli diet. The glial activation markers GFAP (Mm.PT.56a.6609337.q), CD11b (Mm.PT.56a.9189361), MHC-II (Mm.PT.56a.43429730), and CX3CR1 (Mm.PT.56a.17555544) were used to determine whether astrocyte and microglial activation was affected by dietary intervention. All genes were analyzed using PrimeTime qPCR Assays (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and were compared to the housekeeping control gene GAPDH (Mm.PT.39.a.1) using the 2−ΔΔCt calculation method as previously described [24]. Data are expressed as fold change versus control diet mice treated with saline.

2.5 Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS, Cary, NC). Data were subjected to three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for main effects of age, diet, and LPS, and all 2- and 3-way interactions. Where ANOVA revealed a significant interaction, post hoc Student’s t test using Fisher’s least significant differences was used to determine mean separation. All data are expressed as means ± standard error of mean (SEM).

3. Results

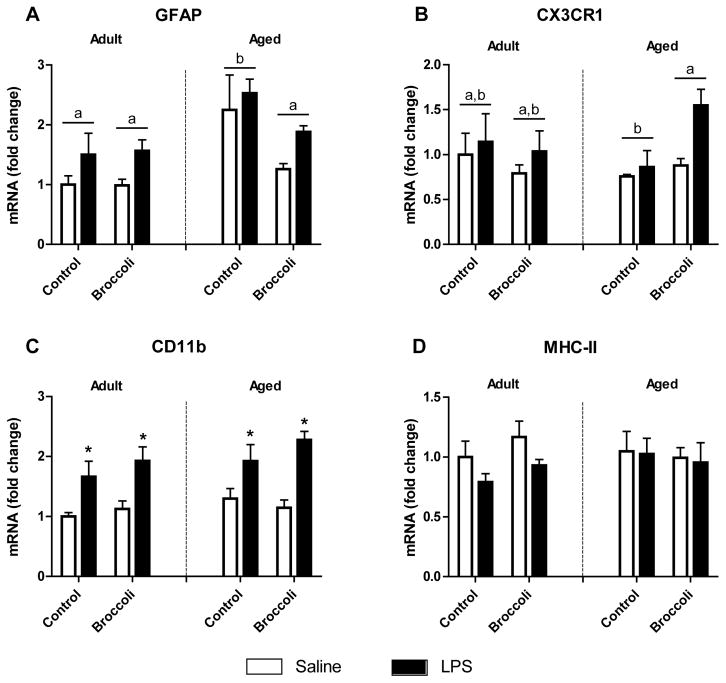

3.1 LPS increased glial markers while broccoli diet reduced GFAP and increased CX3CR1 mRNA in aged mice

ARE gene expression is elevated in glial cells treated with SFN, indicating that glia may be sensitive to the protective benefits of SFN [25–27]. Because glial cells are also the predominant producers of proinflammatory mediators in brain, we measured expression of several markers of glial reactivity. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was elevated in brain of aged mice (p < 0.001). Interestingly, broccoli diet lowered expression of GFAP in aged mice (Age x Diet interaction, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1). To determine whether dietary broccoli could decrease neuroinflammation in response to systemic LPS, we measured markers of glia reactivity in LPS or saline treated mice. GFAP was increased in mice given LPS (p < 0.05). The microglial activation markers MHC-II and CD11b were quantified to examine reactivity in microglia. MHC-II expression was not changed 24 h following LPS, but LPS did induce higher CD11b expression (p < 0.0001). Diet had no effect on the expression of these microglial activation markers at 24 h after LPS treatment.

Figure 1. LPS increased glial markers while broccoli diet reduced GFAP and increased CX3CR1 mRNA in aged mice.

A) GFAP was elevated by age (p<0.001) and by LPS (p<0.05). Broccoli diet decreased GFAP in aged mice. B) CX3CR1 increased with LPS (p<0.05). Broccoli diet increased CX3CR1 in aged mice compared to adult controls. C) CD11b was elevated by LPS. D) No change was evident in MHC-II after LPS. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n=5–7). Means with different letters are statistically significant. * p<0.05 compared to adult saline controls.

Fractalkine receptors (CX3CR1) expressed on microglia provide a regulatory mechanism by which microglia activity is regulated in brain. Aged mice reportedly have decreased CX3CR1 resulting in decreased immunoregulatory signals to microglia leading to prolonged activation state following LPS [28]. CX3CR1 was induced by LPS (p < 0.05). Broccoli diet increased CX3CR1 mRNA in aged mice (Age x Diet interaction; p < 0.05), suggesting another potential role of dietary broccoli in reducing glial reactivity.

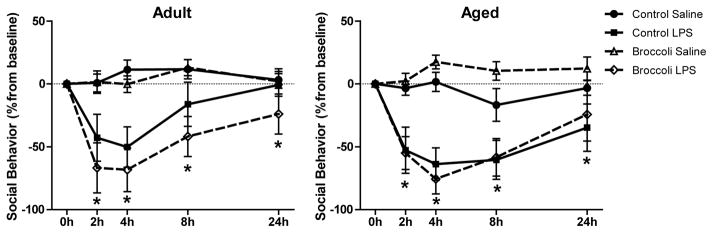

3.2 Broccoli diet did not attenuate LPS-induced reduction in social interactions

To evaluate whether dietary broccoli reduced sickness after an acute peripheral immune challenge, we used the social exploratory test. LPS decreased social investigation 2, 4, 8, and 24 h after LPS (LPS x Time interaction, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Broccoli diet did not significantly influence social behavior.

Figure 2. LPS decreased social interactions similarly in mice fed control or broccoli supplemented diet.

Data are means ± SEM (n=5–7). * indicates LPS x time effect p<0.05 compared to saline controls.

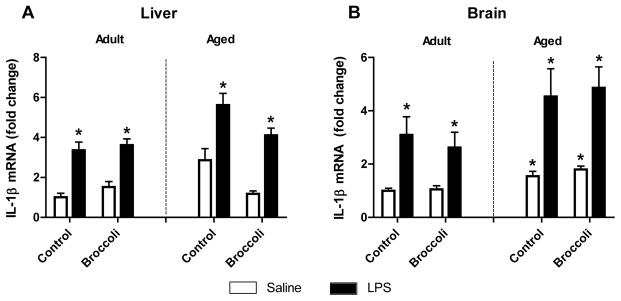

3.3 Age and LPS increased proinflammatory IL-1β mRNA in liver and brain

Because IL-1β is known to play a significant role in sickness behavior, IL-1β expression was quantified in both central and peripheral tissues [29,30]. Aged mice had elevated basal IL-1β in brain (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated increased IL-1β in aged mice and exaggerated expression to LPS [3,6,31]. LPS significantly increased IL-1β mRNA in liver and brain of both adult and aged mice (p < 0.001). The broccoli diet did not affect brain IL-1β levels in control or LPS-treated mice. Although broccoli diet appeared to decrease IL-1β in control and LPS-treated aged mice, there was no main effect of diet and the Age x Diet interaction was not significant (p = 0.12).

Figure 3. IL-1β mRNA was increased in aged mice and all mice given LPS in liver and brain.

A) IL-1β was increased 24 h after LPS in liver (p<0.001) B) IL-1β was elevated in brain of aged mice (p<0.01) and increased 24 h after LPS (p<0.0001). Bars represent means ± SEM (n=5–7). * p<0.05 compared to adult saline controls.

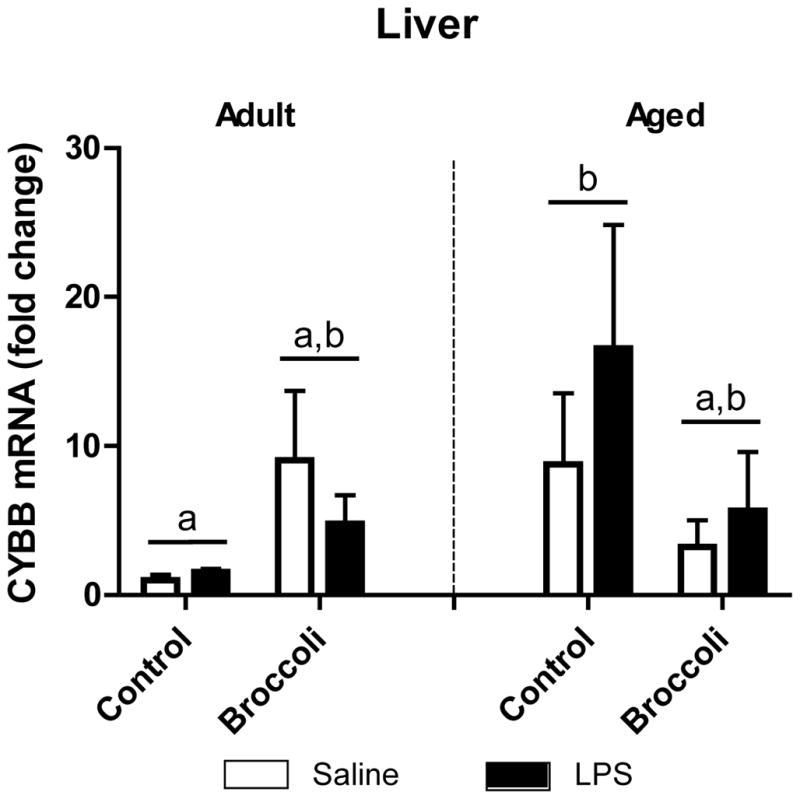

3.4. CYBB was elevated in liver of aged mice

NADPH oxidase generates neurotoxic and hepatotoxic reactive oxygen species that have been implicated in development of chronic disease [32,33]. Cytochrome B-245 β (CYBB) is a functional component of the NADPH oxidase system that contributes to release of free radicals from phagocytic cells. We examined whether broccoli attenuated CYBB expression. An Age x Diet interaction revealed that CYBB expression was increased in the liver of aged control animals compared to adult control animals (p < 0.05), and broccoli diet tended to prevent the elevation in CYBB in aged mice (p < 0.10) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. CYBB was elevated in liver of aged mice.

CYBB was elevated in the aged control diet group compared to adult controls (Age x Diet interaction, p<0.05). In aged mice, broccoli diet tended to decrease CYBB compared to control diet (p<0.10). Values are means ± SEM (n=5–7).

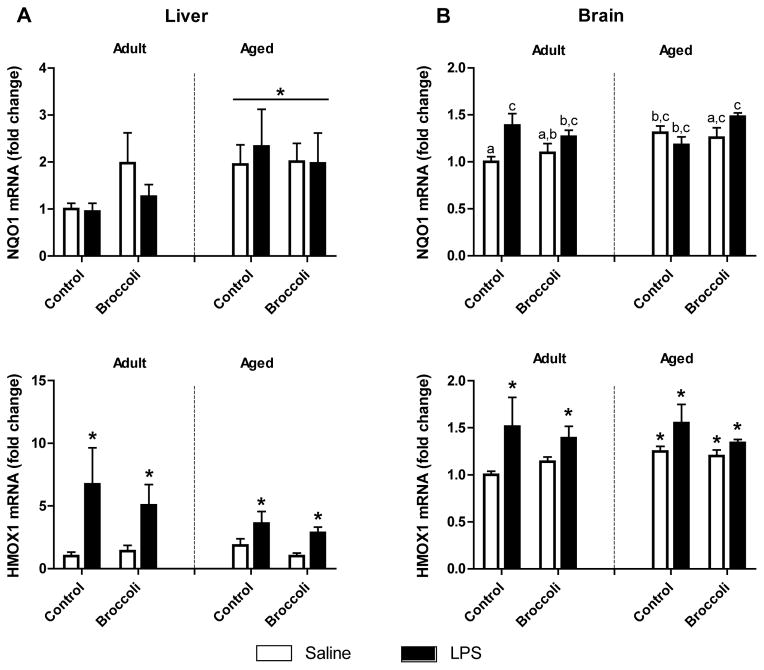

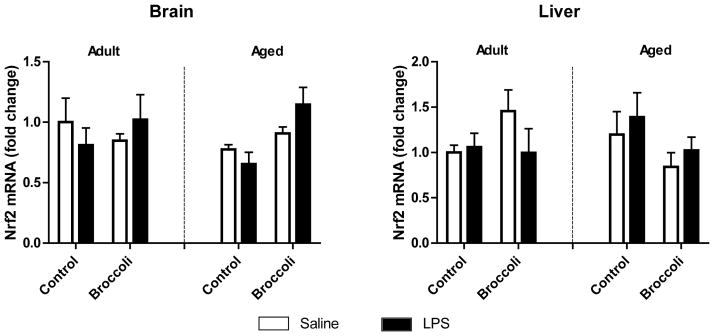

3.5 Broccoli did not significantly influence the Nrf2 pathway

Several studies demonstrate that broccoli consumption increases Nrf2-inducible antioxidant enzyme activity in colon and liver tissue, presumably through SFN absorbed from dietary broccoli [34]. Importantly, SFN also induces Nrf2 antioxidant pathway in brain leading to increased ARE gene expression that provides neuroprotective benefits [35,36]. To determine whether this anti-inflammatory effect is exhibited in brain or periphery of aged mice following dietary broccoli consumption, we measured Nrf2 gene expression after four weeks of control or broccoli diet in mice given LPS or saline. Broccoli diet marginally increased Nrf2 expression in brain of LPS-treated mice, although this increase did not reach significance (p < 0.10). LPS did not induce Nrf2 expression at 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 5). Neither diet, treatment, nor age effected Nrf2 expression in liver.

Figure 5. Broccoli diet did not increase Nrf2 mRNA.

Broccoli and LPS tended to increase Nrf2 in brain 24 h after LPS (Age x Diet interaction p<0.10). Data are represented as means ± SEM (n=5–7).

NQO1 increased in liver of aged mice (p = 0.05). Analysis of brain tissue revealed an Age x Diet x Treatment interaction (p < 0.05), where increased NQO1 expression was most evident in mice fed broccoli diet and given LPS. LPS increased HMOX1 expression in brain and liver (p < 0.01), but dietary broccoli had no affect (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. NQO1and HMOX1 in brain tissue were increased in aged mice and all LPS-treated mice.

A) NQO1 was increased in liver of aged mice (p=0.05). HMOX1 was increased in liver 24 h after LPS (p<0.01). B) NQO1 was increased in brain of aged mice (p<0.05) and was elevated 24 h after LPS (p<0.01). Means with different letters are statistically significant (Age x Diet x LPS interaction p<0.05). Bars represent means ± SEM (n=5–7). * p<0.05 compared to adult saline controls.

4. Discussion

Dietary interventions that reduce aging-related inflammation garner significant research interest. While broccoli and broccoli sprouts are drawing increased interest from medical and nutritional scientists, much of the research focus has been centered on the benefits of dietary broccoli for cancer treatment and prevention. In the present studies, we focused on the anti-inflammatory properties of compounds found in whole broccoli and sought to determine whether a broccoli-supplemented diet was beneficial for attenuating systemic and central inflammation in aged mice. In these studies, four weeks of feeding a 10% freeze-dried broccoli diet mildly improved markers of glial reactivity in aged mice and tended to prevent age-induced increase in hepatic CYBB. In contrast to in vitro studies in which supra-physiological concentrations of SFN reduced LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines, dietary broccoli did not reduce proinflammatory cytokines in mice that were challenged with LPS.

CYBB expression is regulated by a number of transcription factors, including the redox sensitive nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB). Our data and others suggest that CYBB expression increases with age, which may contribute to increased oxidative stress that occurs with age [33,37]. While CYBB expression levels are not a direct indication of ROS, transcriptional regulation of CYBB has a marked impact on ROS production [38,39]. We demonstrate that dietary broccoli may prevent the age-induced elevation in CYBB, which may hold significance for reducing increased oxidative stress associated with aging.

Using both in vitro and in vivo models, SFN conveys Nrf2-dependent neuroprotective effects to cultured astrocytes and microglia and to brain regions including hippocampus, striatum, and cortex [36,40,41]. Consistent with previously published data, we saw transcriptional increases in GFAP in aged mice, suggesting increased astrocyte reactivity [42]. Interestingly, broccoli diet down-regulated LPS-induced GFAP expression in aged mice suggesting that astrocytes may be sensitive to low circulating levels of SFN achieved from consuming dietary broccoli. This finding may demonstrate that based on the juxtaposition of astrocytes with brain blood vessels, astrocytes may be better positioned to respond to the anti-inflammatory effects of SFN. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence to suggest that dietary broccoli influences GFAP. In light of this, it would be interesting to further examine the effects of feeding a broccoli-supplemented diet to mice on changes in surface expression of glial reactivity markers in primary culture. This has been tested to some extent with SFN, but to our knowledge, not with dietary broccoli. We also observed evidence of microglia or perivascular macrophage reactivity. Increased expression of the genetic marker for microglia/macrophage activation, CD11b, was expectedly increased in animals treated with LPS. Expression of CD11b was unaffected by diet suggesting that neither microglia nor brain resident macrophages were responsive to the beneficial effects of a broccoli diet in our model. This was surprising, given that microglia and macrophages are robust producers of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species during inflammatory stimulation. However, these cells are also quite sensitive to LPS induced inflammation and the dose of LPS used may have overwhelmed the beneficial effects of dietary broccoli. These data indicate that gliosis induced by a peripheral stimulus is aggravated by age, and that dietary broccoli may reduce aging-associated glial reactivity.

The fractalkine ligand (CX3CL1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) is an important regulatory system for tempering the microglial response following activation from endogenous and exogenous immune stimuli. Indeed, mice with a genetic deletion of CX3CR1 have an exaggerated microglial inflammatory response and increased duration of sickness behavior compared to wild-type mice. CX3CR1 knockout mice have a similar response to LPS treatment as to that observed in aged animals [28,43,44]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that LPS decreases CX3CR1 at both the mRNA and protein level in microglia [28]. We observed an LPS-induced decrease in CX3CR1 expression in our model that was prevented in aged animals given LPS and fed broccoli diet. These data suggest that aged animals that consume dietary broccoli may have suppressed microglial activation compared to animals that do not consume broccoli in the diet and therefore may have improved long term brain health, e.g. improved neuron survival and increase in neurogenesis, when confronted with infectious disease due to potential suppression of microglial hyperactivity that has been described in aged mice [28,45]. Consumption of broccoli has not been previously reported to upregulate CX3CR1 and it is important to note that additional research is required to determine if the increase in mRNA translates to cell surface expression on primary microglia and whether this change promotes long term brain health due to attenuated microglia activation.

Increased glia reactivity is accompanied by elevated IL-1β [44,46]. Since broccoli diet decreased markers of glial reactivity in aged mice, we examined IL-1β expression to determine if broccoli diet attenuated additional inflammatory mediators. IL-1β is a key inflammatory cytokine in both the peripheral and central immune response [47]. IL-1β induces sickness behaviors such as anorexia, decreased locomotion, and social activity when exogenously administered while inhibition of IL-1β signaling attenuates sickness behaviors in response to LPS treatment [30,48,49]. For these reasons, we hypothesized that broccoli diet would exert an anti-inflammatory benefit by inhibiting IL-1β expression and this would attenuate LPS-induced sickness behaviors. In the present study, decreased social behavior was paralleled by increased IL-1β in brain, but there was no evidence that broccoli diet moderated LPS-induced sickness behavior. It is possible that the dose of LPS used (0.33 mg/kg) overwhelmed the anti-inflammatory dietary effects of consuming broccoli. It is also likely that the anorexic effect of LPS-induced sickness limited broccoli intake, resulting in lowered SFN exposure. Indeed, we observed that 24 h food consumption was decreased in LPS-treated mice compared to saline controls (data not shown). SFN is metabolized and excreted rapidly following broccoli consumption, and metabolites are not retained in tissue past 24 h [50–52]. It seems plausible that diminished intake of broccoli during the 24 h sickness period could account for the lack of effectiveness against acute peripheral inflammation. Our findings are in contrast to other studies where dietary luteolin, resveratrol, or α-tocopherol and selenium improved LPS-induced sickness behavior in aged mice. Collectively these nutritional interventions suggest that dietary supplements are a viable therapeutic vehicle to ameliorate prolonged sickness in aged models [31,53,54]. A more successful approach may be to incorporate SFN in supplement form into the diet. In agreement with this approach, some studies have demonstrated reduced neuroinflammation using purified SFN given intraperitoneally at doses of 50 mg/kg, which is several-fold higher than could be reasonably obtained through the 10% broccoli diet [36,41]. It remains to be determined whether the concentrations of SFN that were necessary to achieve reductions in inflammatory markers in these studies can be obtained through voluntary dietary consumption.

Broccoli was selected for this study because it is a frequently consumed glucoraphanin-containing vegetable [55,56]. Although the SFN-precursor glucoraphanin is more concentrated in broccoli sprouts compared to broccoli, high glucosinolate content adds additional bitterness to the taste of the sprout, making it less palatable than broccoli [12,57]. Preparation of freeze-dried broccoli has been optimized to preserve glucosinolates and prevent inactivation of myrosinase. This is particularly important because SFN is not stable and is more bioactive when fed to rats in its glucosinolate precursor form than when hydrolyzed prior to being fed to rodents [34]. Addition of 10–20% freeze-dried broccoli to rodent diet has been reported to increase activity of hepatic and colonic ARE enzymes [58–60]. In contrast to these reports, 10% broccoli diet utilized in our studies did not increase ARE genes in brain or liver tissue of aged mice. However, in this study, HMOX1 was induced by LPS, suggesting that this gene is activated in response to increased oxidative stress generated by LPS-induced inflammation [61]. HMOX1 is an endogenous antioxidant that inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase in LPS-stimulated macrophages, and higher HMOX1 mRNA and protein is associated with an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype [62–64]. Although HMOX1 is notable as part of the antioxidant cascade activated by Nrf2, HMOX1 mRNA expression was also responsive to inflammation induced by LPS. Induction of HMOX1 by LPS in our model was an expected component in agreement with findings indicating that, in addition to containing a Nrf2-inducible ARE promoter region, HMOX1 is upregulated by the proinflammatory NFκB transcriptional pathway that is strongly activated by LPS [65]. Based on our findings, HMOX1 appears to be more transcriptionally responsive to activation of NFκB during inflammation than to 10% broccoli diet. A 10% broccoli diet may be insufficient to elevate SFN levels in circulation to temper acute inflammation in mice. In agreement with this suggestion, Innamorato et al. reported that HMOX1 protein is induced in the brain by a high dose of SFN injected i.p. [36], but there are no published data reporting in vivo induction of HMOX1 transcription and translation following low doses of SFN such as that obtained when consuming broccoli supplemented diet. A clinical study that examined gene expression in gastric mucosa after consumption of broccoli soup reported that while several antioxidant genes were elevated in gastric mucosa, only a fraction of genes previously induced by SFN in vitro were altered by the broccoli soup [66]. It is evident that additional pre-clinical and clinical studies are needed to determine effective timing and dosage of broccoli inclusion in the diet.

Another explanation for the lack of ARE gene expression induced by broccoli diet is that other peripheral tissues, such as intestine or resident macrophages of the peritoneum, may be more sensitive to broccoli supplemented diet. Several phamacokinetic studies report that SFN metabolites are widely distributed in tissues following orally administered SFN, but bioactivity in these tissues is not well-established and distribution of SFN does not appear to correlate with tissue-specific bioactivity [52,67]. Based on our findings, dietary broccoli is insufficient to upregulate HMOX1 and NQO1 in liver and brain. Future studies will help to determine if broccoli supplemented diets are more beneficial in low-grade peripheral inflammatory conditions than acute conditions such as LPS.

An apparent limitation to this study is that reduced food intake is part of the natural sickness response to LPS. Decreased intake of dietary broccoli in LPS-injected mice on the final day of the study may have interfered with acute effects that would have been apparent if the mice ate as usual. The overall lack of effects due to dietary broccoli may have been due to reduced food intake.

In summary, we have demonstrated that consumption of a 10% broccoli diet mildly reduced neuroinflammation in aged mice by preventing upregulation reactive glia markers. However, we did not find evidence to support our hypothesis that LPS-induced inflammatory markers and sickness behavior could be attenuated by dietary broccoli. While these data do not support a role for broccoli consumption in suppressing sickness behaviors associated with an LPS-induced acute inflammatory response, they do not rule out that components found in broccoli, such as SFN, may be beneficial when consumed in pharmacological doses via supplementation. Taken together, our data suggest potential health benefits for the aged human population using dietary broccoli to improve the low-grade neuroinflammation that is associated with aging.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Edward Dosz for analysis of SFN content of broccoli used in the experimental diets. Thanks to Marcus Lawson for editing assistance. This study was supported by NIH grant AG16710 to RWJ and USDA/NIFA 2010-65200-20398 to EHJ.

Abbreviations

- ARE

antioxidant response element

- CX3CR1

fractalkine receptor

- CYBB

cytochrome b-245 β

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HMOX1

heme oxygenase I

- IL

interleukin

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MHC-II

major histocompatibility complex II

- NQO1

NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

- qPCR

real-time quantitative RT-PCR

- SEM

standard error of mean

- SFN

sulforaphane

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared

References

- 1.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:7915–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harman D. Free radicals in aging. Mol Cell Biochem. 1988;84:155–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00421050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Buchanan JB, Sparkman NL, Godbout JP, Freund GG, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation and disruption in working memory in aged mice after acute stimulation of the peripheral innate immune system. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:301–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan JB, Sparkman NL, Chen J, Johnson RW. Cognitive and neuroinflammatory consequences of mild repeated stress are exacerbated in aged mice. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2008;33:755–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effros RB, Walford RL. Diminished T-cell response to influenza virus in aged mice. Immunology. 1983;49:387–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godbout JP, Chen J, Abraham J, Richwine AF, Berg BM, Kelley KW, et al. Exaggerated neuroinflammation and sickness behavior in aged mice following activation of the peripheral innate immune system. FASEB J. 2005;19:1329–31. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3776fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilger RN, Johnson RW. Aging, microglial cell priming, and the discordant central inflammatory response to signals from the peripheral immune system. J Leukocyte Biol. 2008;84:932–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calkins MJ, Johnson DA, Townsend JA, Vargas MR, Dowell JA, Williamson TP, et al. The Nrf2/ARE pathway as a potential therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disease. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2009;11:497–508. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh JH, Shenvi SV, Dixon BM, Liu H, Jaiswal AK, Liu R-M, et al. Decline in transcriptional activity of Nrf2 causes age-related loss of glutathione synthesis, which is reversible with lipoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:3381–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400282101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs L, Gautam T, Sosnowska D, Wang M, Monticone RE, et al. Age-associated vascular oxidative stress, Nrf2 dysfunction, and NF-κB activation in the nonhuman primate Macaca mulatta. J Gerontol A-Biol. 2011;66A:866–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedl MA, Saxon A, Diaz-Sanchez D. Oral sulforaphane increases Phase II antioxidant enzymes in the human upper airway. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahey JW, Zhang Y, Talalay P. Broccoli sprouts: An exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:10367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talalay P, Fahey JW, Healy ZR, Wehage SL, Benedict AL, Min C, et al. Sulforaphane mobilizes cellular defenses that protect skin against damage by UV radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:17500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiss E, Herhaus C, Klimo K, Bartsch H, Gerhäuser C. Nuclear factor κB is a molecular target for sulforaphane-mediated anti-inflammatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32008–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin W, Wu RT, Wu T, Khor T-O, Wang H, Kong A-N. Sulforaphane suppressed LPS-induced inflammation in mouse peritoneal macrophages through Nrf2 dependent pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:967–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerrero-Beltran CE, Calderon-Oliver M, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Chirino YI. Protective effect of sulforaphane against oxidative stress: recent advances. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2012;64:503–8. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffery E, Araya M. Physiological effects of broccoli consumption. Phytochem Rev. 2009;8:283–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.London SJ, Yuan J-M, Chung F-L, Gao Y-T, Coetzee GA, Ross RK, et al. Isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms, and lung-cancer risk: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Lancet. 2000;356:724–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh E, Wimalasiri KMS, Chassy AW, Mitchell AE. Content of ascorbic acid, quercetin, kaempferol and total phenolics in commercial broccoli. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2009;22:637–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambrosone CB, McCann SE, Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, Zhang Y, Shields PG. Breast cancer risk in premenopausal women is inversely associated with consumption of broccoli, a source of isothiocyanates, but is not modified by GST genotype. J Nutr. 2004;134:1134–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tse G, Eslick GD. Cruciferous vegetables and risk of colorectal neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:128–39. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.852686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dosz EB, Jeffery EH. Modifying the processing and handling of frozen broccoli for increased sulforaphane formation. J Food Sci. 2013;78:H1459–63. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S-E, Dantzer R, Kelley K, McCusker R. Central administration of insulin-like growth factor-I decreases depressive-like behavior and brain cytokine expression in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jurgens HA, Amancherla K, Johnson RW. Influenza infection induces neuroinflammation, alters hippocampal neuron morphology, and impairs cognition in adult mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3958–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6389-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergström P, Andersson HC, Gao Y, Karlsson J-O, Nodin C, Anderson MF, et al. Repeated transient sulforaphane stimulation in astrocytes leads to prolonged Nrf2-mediated gene expression and protection from superoxide-induced damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:343–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraft AD, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2-dependent antioxidant response element activation by tert-butylhydroquinone and sulforaphane occurring preferentially in astrocytes conditions neurons against oxidative insult. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1101–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3817-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konwinski RR, Haddad R, Chun JA, Klenow S, Larson SC, Haab BB, et al. Oltipraz, 3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione, and sulforaphane induce overlapping and protective antioxidant responses in murine microglial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2004;153:343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wynne AM, Henry CJ, Huang Y, Cleland A, Godbout JP. Protracted downregulation of CX3CR1 on microglia of aged mice after lipopolysaccharide challenge. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley KW, Hutchison K, French R, Bluthe RM, Parnet P, Johnson RW, et al. Central interleukin-1 receptors as mediators of sickness. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;823:234–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham J, Johnson RW. Central inhibition of interleukin-1beta ameliorates sickness behavior in aged mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang S, Dilger RN, Johnson RW. Luteolin inhibits microglia and alters hippocampal-dependent spatial working memory in aged mice. J Nutr. 2010;140:1892–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kono H, Rusyn I, Yin M, Gäbele E, Yamashina S, et al. NADPH oxidase–derived free radicals are key oxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:867–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin L, Liu Y, Hong J-S, Crews FT. NADPH oxidase and aging drive microglial activation, oxidative stress, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration following systemic LPS administration. Glia. 2013;61:855–68. doi: 10.1002/glia.22479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keck A-S, Qiao Q, Jeffery EH. Food matrix effects on bioactivity of broccoli-derived sulforaphane in liver and colon of F344 rats. J Agr Food Chem. 2003;51:3320–7. doi: 10.1021/jf026189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dash PK, Zhao J, Orsi SA, Zhang M, Moore AN. Sulforaphane improves cognitive function administered following traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Lett. 2009;460:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Innamorato N, Rojo AI, Garcia-Yague AJ, Yamamoto M, de Ceballos ML, Cuadrado A. The transcription factor Nrf2 is a therapeutic target against brain inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;181:680–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim D, You B, Jo E-K, Han S-K, Simon MI, Lee SJ. NADPH oxidase 2-derived reactive oxygen species in spinal cord microglia contribute to peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14851–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009926107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guichard C, Moreau R, Pessayre D, Epperson TK, Krause KH. NOX family NADPH oxidases in liver and in pancreatic islets: a role in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes? Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:920–9. doi: 10.1042/BST0360920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anrather J, Racchumi G, Iadecola C. NF-κB Regulates Phagocytic NADPH Oxidase by Inducing the Expression of gp91phox. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5657–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danilov CA, Chandrasekaran K, Racz J, Soane L, Zielke C, Fiskum G. Sulforaphane protects astrocytes against oxidative stress and delayed death caused by oxygen and glucose deprivation. Glia. 2009;57:645–56. doi: 10.1002/glia.20793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jazwa A, Rojo AI, Innamorato NG, Hesse M, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Cuadrado A. Pharmacological targeting of the transcription factor Nrf2 at the basal ganglia provides disease modifying therapy for experimental parkinsonism. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2011;14:2347–60. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Callaghan JP, Miller DB. The concentration of glial fibrillary acidic protein increases with age in the mouse and rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 1991;12:171–4. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(91)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–24. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corona AW, Huang Y, O’Connor JC, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Popovich PG, et al. Fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) deficiency sensitizes mice to the behavioral changes induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Neuroinflamm. 2010;7:93. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne AM, Godbout JP. Peripheral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge promotes microglial hyperactivity in aged mice that is associated with exaggerated induction of both pro-inflammatory IL-1β and anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokines. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SC, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF. Interleukin-1, nitric oxide and reactive astrocytes. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:345–54. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goshen I, Yirmiya R. Interleukin-1 (IL-1): a central regulator of stress responses. Front Neuroendocrin. 2009;30:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segreti J, Gheusi G, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Johnson RW. Defect in interleukin-1β secretion prevents sickness behavior in C3H/HeJ mice. Physiol Behav. 1997;61:873–8. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burgess W, Gheusi G, Yao J, Johnson RW, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme-deficient mice resist central but not systemic endotoxin-induced anorexia. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R1829–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.6.R1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veeranki OL, Bhattacharya A, Marshall JR, Zhang Y. Organ-specific exposure and response to sulforaphane, a key chemopreventive ingredient in broccoli: implications for cancer prevention. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:25–32. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, Zhang T, Li X, Zou P, Schwartz SJ, Sun D. Kinetics of sulforaphane in mice after consumption of sulforaphane-enriched broccoli sprout preparation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:2128–36. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clarke J, Hsu A, Williams D, Dashwood R, Stevens J, Yamamoto M, et al. Metabolism and tissue distribution of sulforaphane in Nrf2 knockout and wild-type mice. Pharm Res. 2011;28:3171–9. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0500-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abraham J, Johnson RW. Consuming a diet supplemented with resveratrol reduced infection-related neuroinflammation and deficits in working memory in aged mice. Rejuv Res. 2009;12:445–53. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg BM, Godbout JP, Chen J, Kelley KW, Johnson RW. α-Tocopherol and selenium facilitate recovery from lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness in aged mice. J Nutr. 2005;135:1157–63. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Latté KP, Appel K-E, Lampen A. Health benefits and possible risks of broccoli – An overview. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:3287–309. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNaughton SA, Marks GC. Development of a food composition database for the estimation of dietary intakes of glucosinolates, the biologically active constituents of cruciferous vegetables. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:687–97. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drewnowski A, Gomez-Carneros C. Bitter taste, phytonutrients, and the consumer: a review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72:1424–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matusheski NV, Jeffery EH. Comparison of the bioactivity of two glucoraphanin hydrolysis products found in broccoli, sulforaphane and sulforaphane nitrile. J Agr Food Chem. 2001;49:5743. doi: 10.1021/jf010809a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramsdell HS, Eaton DL. Modification of aflatoxin B1 biotransformation in vitro and DNA binding in vivo by dietary broccoli in rats. J Toxicol Env Health. 1988;25:269–84. doi: 10.1080/15287398809531209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vang O, Mehrota K, Georgellis A, Andersen O. Effects of dietary broccoli on rat testicular xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes. Eur J Drug Metab Ph. 1999;24:353. doi: 10.1007/BF03190044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rushworth SA, MacEwan DJ, O’Connell MA. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and heme oxygenase-1 protects against excessive inflammatory responses in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:6730–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sierra-Filardi E, Vega MA, Sánchez-Mateos P, Corbí AL, Puig-Kröger A. Heme Oxygenase-1 expression in M-CSF-polarized M2 macrophages contributes to LPS-induced IL-10 release. Immunobiology. 2010;215:788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soares MP, Marguti I, Cunha A, Larsen R. Immunoregulatory effects of HO-1: how does it work? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turcanu V, Dhouib M, Poindron P. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition by haem oxygenase decreases macrophage nitric-oxide-dependent cytotoxicity: a negative feedback mechanism for the regulation of nitric oxide production. Res Immunol. 1998;149:741–4. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(99)80050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lavrovsky Y, Song CS, Chatterjee B, Roy AK. Age-dependent increase of heme oxygenase-1 gene expression in the liver mediated by NFkappaB. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;114:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gasper AV, Traka M, Bacon JR, Smith JA, Taylor MA, Hawkey CJ, et al. Consuming broccoli does not induce genes associated with xenobiotic metabolism and cell cycle control in human gastric mucosa. J Nutr. 2007;137:1718–24. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu R, Hebbar V, Kim B-R, Chen C, Winnik B, Buckley B, et al. In vivo pharmacokinetics and regulation of gene expression profiles by isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:263–71. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]