Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the prevalence of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, as well as the time to awakening, short-term neurologic outcomes, and cause of death in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital resuscitated cardiopulmonary arrests treated with therapeutic hypothermia.

Design

Single center, prospective observational cohort study of consecutive patients with out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests.

Setting

Academic tertiary care hospital and level one trauma center in Minneapolis, MN.

Patients

Adults with witnessed, nontraumatic, out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests regardless of initial electrocardiographic rhythm with return of spontaneous circulation who were admitted to an ICU.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

The study cohort included 154 comatose survivors of witnessed out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests who were admitted to an ICU during the 54-month study period. One hundred eighteen patients (77%) were treated with therapeutic hypothermia. The mean age was 59 years, 104 (68%) were men, and 83 (54%) had an initial rhythm of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Only eight of all 78 patients (10%) who died qualified as brain dead; and 81% of all patients (63 of 78) who died did so after withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. Twenty of 56 comatose survivors (32%) treated with hypothermia who awoke (as defined by Glasgow Motor Score of 6) and had good neurologic outcomes (defined as Cerebral Performance Category 1–2) did so after 72 hours.

Conclusions

Our study supports delaying prognostication and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment to beyond 72 hours in cases treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Larger multicenter prospective studies are needed to better define the most appropriate time frame for prognostication in comatose cardiac arrest survivors treated with therapeutic hypothermia. These data are also consistent with the notion that a majority of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest survivors die after a decision to withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment and that very few of these survivors progress to brain death.

Keywords: brain death, cardiac arrest, outcome, prognostication, therapeutic hypothermia, withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment

Out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests (OHCA) pose a significant public health burden, with an estimated annual prevalence of over 380,000 arrests evaluated by emergency medical services in the United States alone (1–4). In the decade following the 2002 landmark trials of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) to improve outcomes in comatose cardiac arrest survivors, little additional progress has been made in finding and implementing successful new neuroprotective interventions (5, 6). Therefore, TH remains the only proven neuroprotective strategy available and the focus of the resuscitation community. A number of factors explain this lack of progress: a lack of understanding of the mechanisms and circumstances leading to poor outcomes, lead time and selection biases, as well as funding and ethical considerations that make research in this field quite challenging (7–10). Finally, and most importantly, studies necessarily lack complete data on patients from whom they withdrew life-sustaining therapy before the effect of TH could be fully realized; this is the “self-fulfilling prophesy”; if care is withdrawn too early, it is impossible to know if further care would result in a higher rate of neurologically intact survival.

The existing American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2006 guidelines for the Prediction of Outcome in Comatose Survivors After Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation have only been studied in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest who have not been treated with TH (11). These guidelines recommend prognostication and decision making at 72 hours postarrest. However, the timing of clinical, electrophysiologic, and biomarker testing for neurologic prognostication during the first 72 hours postarrest have not been validated for patients who have undergone TH. The ideal paradigm for prognosticating neurologic outcomes in comatose cardiac arrest survivors treated with TH is unknown despite several studies that have tried to shed light on this crucial question (12–18). These studies have several important flaws: a lack of blinding to the results of the prognostic markers being evaluated (13, 16, 19–22), the high proportion of patients who have withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy (WLST) (12, 13, 19, 23), and a lack of understanding regarding the number of patients who die of a true neurologic cause defined brain death as opposed to WLST, cardiac, respiratory, infectious, or other causes. There are no adequate clinical data to prove or refute the notion that TH decreases the proportion of patients who progress to “brain death,” and as such, our understanding of how TH improves mortality and neurologic outcomes remains inadequate.

The aim of the study was to test the hypothesis that treatment of comatose OHCA survivors with TH may result in awakening beyond 72 hours, with good neurologic outcomes assessed by Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) at hospital discharge. Additional objectives are to describe times to WLST, causes of death, and the proportion of patients who progressed to brain death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a prospective observational cohort consisting of all adult patients brought to the Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) emergency department (ED) after resuscitated, nontraumatic OHCA. HCMC is an academic tertiary care hospital and level one trauma center in Minneapolis, MN. All consecutive adult survivors of nontraumatic OHCA treated at HCMC from July 2007 through December 2011 were considered for inclusion in this study. Approval for this study was obtained from the HCMC Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria for this study were age of 18 years and older, witnessed arrest and successful resuscitation as defined by a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and an ongoing loss of consciousness as defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale motor score (mGCS) equal or less than 5 in the ED after ROSC (24). Exclusion criteria were intracranial hemorrhage and baseline CPC equal to or greater than 3.

Although this study did not specify any of the therapeutic or diagnostic interventions to be performed due to its observational nature, all patients followed the standard institutional TH protocol. This protocol specified propofol as the sedative agent of choice and midazolam as the preferred alternative agent. For patients under neuromuscular blockade (NMB), the minimum dose of propofol was 40 μg/kg/min, and a minimum dose of 20 μg/kg/min to be used in the absence of NMB. In the case of midazolam, the minimal dose to be used during NMB was 5 mg/ hr and a minimum infusion of 1 mg/hr to be used in the absence of NMB. Fentanyl at a starting dose of 50 μg/hr was used in all patients during TH, with down titration as able after rewarming to maintain patient comfort. Sedation was to be titrated to patient comfort, ventilator synchrony, and as an adjunct to avoid shivering during induction and rewarming of TH. Sedation was aggressively titrated down and stopped completely whenever possible until patients awoke, after which they were titrated to the minimum necessary until extubation, with daily interruptions of sedation unless otherwise clinically contraindicated. After completion of rewarming, fentanyl was the preferred agent to maintain comfort during mechanical ventilation. Atracurium was the paralytic of choice when necessary and cisatracurium as the agent of choice in cases of renal dysfunction.

TH was initially not offered to patients presenting with initial rhythms of pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole. The decision of initiating TH was left to the discretion of the ED and the intensive care teams; at the start of the study, TH was offered only to ventricular tachycardia (VT)/ventricular fibrillation (VF) arrests. However, the routine application of hypothermia to all comatose OHCA survivors became standard in 2009. Institutional criteria to exclude patients from receiving TH included sustained hypotension with a mean arterial pressure less than 60 mm Hg for greater than 30 minutes after ROSC while on high-dose vasopressors; uncontrolled bleeding; pregnancy; refractory VF (electrical storm); preexisting multiple organ failure, septic shock; do not attempt resuscitation status, terminal illness, or baseline unresponsiveness. Furthermore, patients were excluded if technical issues precluded safe provision of TH (extremes of weight).

Data Collection, Definitions, and Outcomes

Data collected were classified as prearrest, arrest, and postarrest data. Prearrest data included patient demographics and baseline comorbid states including history of known hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and end-stage renal dysfunction on hemodialysis. Arrest data collected included the following: initial rhythm, time to ROSC, and if the arrest was witnessed or not. Postarrest data collected were as follows: use of TH and ICU length of stay, awakening (defined as wakefulness and a consistent motor GCS score of 6 on serial assessments), information pertaining to discharge destination (home, nursing home, or subacute rehabilitation facility) or if the patient expired; and time from admission to one of these endpoints. Neurologic outcomes were classified according to the Glasgow-Pittsburgh CPC scores, with a “good” clinical outcome reflective of a CPC score of 1–2. CPC scores greater than or equal to 3 were consistent with a poor outcome (i.e., 3 = severe cerebral disability, 4 = coma or a vegetative state, 5 = brain death or death defined by traditional criteria) (24–26). Discharge outcomes were based on a combination of physical and occupational therapy, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and neurologic evaluations prior to discharge as documented in the electronic medical record. In the patients with OHCA who died, we examined the process by which they progressed to death. Patients who were declared brain dead were declared to be so after an initial examination and a second confirmatory examination performed by the neurology or neurosurgery consult service in accordance to established national and institutional guidelines (27). Patients were considered unsupportable when they died as defined by traditional criteria (not brain death) while on full support and despite maximal medical interventions. Finally, patients were considered to have had WLST when limitation of medical interventions was agreed upon between the treating team and the patient’s legal decision maker or based on existing adequately supported advance directives from the patient.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test for dichotomous variables, with use of the Fisher exact test reported as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Student t test (two-tailed) if normally distributed and the Mann-Whitney U test if not normally distributed. Time to awakening was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazard model. Censoring events for this analysis included death by any mechanism, including withdrawal of care, as well as hospital discharge prior to awakening. All statistical analyses were done using Stata IC 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

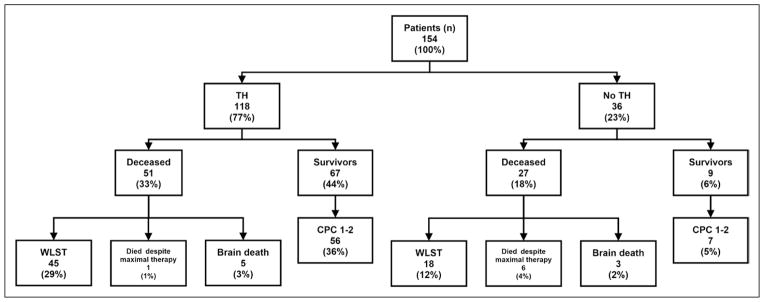

During the 54-month study period, 423 consecutive, adult nontraumatic patients with OHCA were evaluated and treated in the ED. Of those, 154 were witnessed arrests that survived to ICU admission and met all inclusion criteria as well as having complete datasets (Fig. 1). Of the 154 patients included, 76 patients (49%) were discharged alive and 63 (41%) had good neurologic outcomes (CPC, 1–2). The demographic characteristics and associated comorbidities of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. Patients treated with hypothermia were younger than patients not treated with hypothermia. Patients who did not undergo hypothermia were more likely to have had an initial rhythm of PEA/asystole. The mean hospital length of stay was 15.86 days (95% CI, 13.21–18.5 d). The time to awakening did not differ between TH and non-TH groups (p = 0.194). It is critical, however, to note that all of the patients who did not undergo TH and awoke did so before 72 hours, whereas more than a third of those with good recovery in the TH group awoke beyond 72 hours. Of 56 patients treated with TH who had good neurologic outcomes, 20 (36%) awoke after 72 hours, whereas all seven of the seven patients who had good neurologic outcomes in the normothermic group awoke before 72 hours (Table 2). Seventy-six patients (49%) in total (treated with and without TH) survived to hospital discharge; however, it should also be noted that a patient with a VT/VF arrest who underwent TH and one who had a PEA/asystolic arrest with subsequent TH were discharged without recovering consciousness at 22 and 27 days postarrest, respectively.

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment into therapeutic hypothermia use or no therapeutic hypothermia use. Data are (n). CPC = Cerebral Performance Category, ROSC = return of spontaneous circulation.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of Study Cohort

| Study Characteristic | All Patients (n = 154) | TH (n = 118) | No TH (n = 36) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr; mean ± sd | 59±16 | 57±15 | 64±17 | 0.03a |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (32) | 40 (34) | 10 (28) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||||

| History of hypertension | 74 (48) | 58 (49) | 16 (44) | 0.62 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 29 (19) | 23 (19) | 6 (17) | 0.70 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 22 (14) | 15 (13) | 7 (19) | 0.31 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 36 (23) | 30 (25) | 6 (17) | 0.28 |

| History of end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis | 7 (5) | 5 (4) | 2 (6) | 0.74 |

|

| ||||

| Characteristics of arrest | ||||

| Initial rhythm ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 83 (54) | 74 (62) | 9 (25) | 0.0001a |

| Initial rhythm pulseless electrical activity/asystole, n (%) | 71 (46) | 44 (38) | 27 (75) | 0.0001a |

| Time to return of spontaneous circulation; min; mean ± sd | 23±17 | 23±17 | 26±21 | 0.25 |

TH = therapeutic hypothermia.

Denotes statistical significance.

TABLE 2.

Awakening According to Therapeutic Hypothermia and Neurologic Outcomes

| Discharge Cerebral Performance Category, n (%) | Awakening Within 72 Hr | Awakening After 72 Hr | Total | p | Awakening Within 72 Hr | Awakening After 72 Hr | Total | p | Awakening Within 72 Hr | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| TH + No TH | TH | No TH | ||||||||

| 1 | 27 (55.1) | 9 (36) | 36 (48.65) | 23 (57.5) | 9 (36) | 32 (49.23) | 4 (44.44) | 4 (44.44) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 | 16 (32.65) | 11 (44) | 27 (36.49) | 13 (32.5) | 11 (44) | 24 (36.92) | 3 (33.33) | 3 (33.33) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 3 | 6 (12.24) | 5 (20) | 11 (14.86) | 4 (10) | 5 (20) | 9 (13.85) | 2 (22.22) | 2 (22.22) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | 49 (100) | 25 (100) | 74 (100) | 0.298 | 40 (100) | 25 (100) | 65 (100) | 0.245 | 9 (100) | 9 (100) |

TH = therapeutic hypothermia.

Of 118 patients who received TH, 45 (38%) had WLST and of those five (4%) had WLST during the first 72 hours postarrest. In the group of 36 patients who did not receive TH, 18 (50%) had WLST and 14 of the 18 (39% of the total of 36) had WLST in the initial 72 hours postarrest. For those who underwent TH, the mean time to WLST was 7.62 days (95% CI, 5.72–9.53 d), and for those who did not undergo TH, it was a mean of 1.61 days (95% CI, 0.42–2.81 d). Patients who did not undergo TH were significantly more likely to have WLST in the first 72 hours than patients treated with TH (two-tailed Fisher exact test; p = 0.0001). Of 63 patients who underwent WLST, 19 (30%) did so during the first 72 hours postarrest, including five patients who had undergone TH. Three of the 19 patients who had care withdrawn in the first 72 hours had preexisting “do-not-resuscitate” directives that had been unknown to prehospital and ED personnel. The remaining 16 patients had care withdrawn based on family input, and specific reasons were clearly cited in five cases (two due to underlying terminal illness, two due to other comorbidities, and one due to age of 92). Ten percent of patients (8 of 78) resuscitated from OHCA progressed to brain death (Fig. 2). Only 9% (7 of 78) died despite ongoing aggressive therapy, and the remaining 81% of patients (63 of 78) who died in this cohort did so after withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

Figure 2.

Causes of death and neurologic outcomes. Data are number of patients and percentages. CPC = Cerebral Performance Category, TH = therapeutic hypothermia, WLST = withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 36% of all patients treated with TH who had good neurologic outcomes (CPC, 1–2) awoke after the first 72 hours. This suggests that an observation period of only 72 hours might not be adequate in the post-TH era. This study supports existing opinions that delayed neurologic recovery after TH is possible due to a variety of factors including sedation, alterations in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, as well as the effects of hypothermia itself despite a lack of solid evidence as to the exact mechanism of the delay (13, 19, 28–30). These findings are important because current practice favors neurologic prognostication at 72 hours often leading to subsequent and potentially premature WLST (7). This in turn could negatively impact a significant number of patients who could otherwise have gone on to have a good neurologic recovery.

New advances in neuroprotection are hindered by a lack of understanding of how TH alters the natural history of the post–cardiac arrest syndrome. Understanding the time to awakening in comatose survivors post-TH is crucial to knowing when prognostication efforts and plans for WLST become appropriate. These findings as well as those of other recent small studies serve as a base for future controlled studies to determine when prognostic testing is to be performed as well as when to start considering WLST (31, 32). Although not controlling for sedation regimens, duration, cumulative doses, and renal function is a shortcoming in this study, it does reflect clinical practice. No patients in the study received pharmacologic agents such as amantadine, modafenil, or methylphenidate to stimulate arousal (33).

Our data highlight the high number of comatose cardiac arrest survivors who die following WLST decisions (34). Many clinical trials of prognostic strategies in comatose cardiac arrest survivors treated with TH have equally high rates of WLST, and furthermore, the majority of those studies are unblinded and subject to “self-fulfilling prophecies” of poor outcomes (7, 35–38). Equally concerning is the observation that patients are having life-sustaining therapies withdrawn while still undergoing TH; this finding in our study mirrors many other studies as well as clinical practice where this is not a rare event (39). The high percentage of patients who undergo WLST without a good understanding of when and how to prognosticate neurologic outcomes in patients treated with TH may well be an important factor contributing to the large number of negative trials in the field. To put this in perspective, the largest trial to date in the field, that is, the TTM trial by Nielsen et al (40), cites WLST as the cause of death in 247 patients (26%) of the 939 patients recruited; however, this includes patients who were declared brain dead and those who were “unsupportable” due to multiple organ failure and hemodynamic failure (online supplement in [40]). If, as in the case of our study, these two groups are excluded and only patients who had WLST due to comorbidities and neurologic or ethical concerns are considered, then WLST was effectively only undertaken in 94 of 939 patients (10%). Until evidence-based recommendations on when and how to prognosticate neurologic outcomes in patients treated with TH are available, a more conservative approach to WLST may be indicated. It is also worth mentioning that in a recent study by Howell et al (41) carried out at a German neurorehabilitation center, of 113 patients admitted with disorders of consciousness following anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, as many as 6.2% of patients achieved good functional outcomes (Glasgow Outcome Scale, 4–5) with improvements being noted beginning at 8–12 weeks postanoxic event despite having had initial poor prognostic markers such as somatosensory evoked potentials. Both of these studies highlight our lack of ability to predict functional recovery, the potential for delayed recovery, and the need for further research in this area as indiscriminant delays in WLST will have a significant impact on survivors, their families, and the healthcare system.

Our study reflects current practice where the vast majority of comatose cardiac arrest survivors ultimately die after a WLST decision, and only 9% of patients die despite ongoing care and 10% progress to brain death. Gaining an understanding of how, when, and why patients die after initial resuscitation regardless of the use of TH is critical to enable the design and execution of therapeutic trials and also for delivery of care systems in patients with the recently recognized “post–cardiac arrest syndrome” (2). The results of our observational study differ significantly from the existing literature (42, 43) in that our use of a stringent definition for brain injury leading to death (declaration of brain death) eliminated potential confounders, biases, and ambiguity. This is crucial, as without a clear understanding of the mechanisms and circumstances leading to death and poor outcomes, we cannot conceive new therapeutic interventions and processes to intervene in appropriate steps of the pathophysiologic process.

The present study’s main limitations are that it is a single-center observational study focused mainly on end-of-life issues, withdrawal of care, and causes of death in OHCA survivors. Despite being conducted at a single center, we feel the practices are representative of a significant proportion of hospitals that serve as reference centers for the care of resuscitated OHCA survivors. The study does not focus on or include details of management, particularly sedative medications. We also acknowledge that the sample size is a limitation, but the data have generated important observations that may have impact on future studies. The observational nature of this study provides a realistic representation of day-to-day clinical practice. The high rate and early timing of WLST in the TH group render comparisons between the two groups very difficult; however, the aim of the present study is not to compare these groups but rather to highlight the inadequacies of prognostication at 72 hours after TH. This study is also one of the few to describe the time to awakening of patients treated with and without TH, as well as the proportion of patients who progress to brain death, and one of the first to describe time to withdrawal of care (28, 31, 32, 40, 42, 43).

This study and the majority of clinical trials and studies on the subject have been unable to accurately account for the multiple effects of TH in postcardiac arrest—be it the mechanisms of neuroprotection or the delay in awakening. It is important for the resuscitation community to consider that without a solid physiopathologic understanding of the effects of the intervention on our patients, many of these questions are unlikely to be answered satisfactorily. We believe that additional breakthroughs in basic and translational science are required to answer the many unanswered questions posed by TH and targeted temperature management.

CONCLUSIONS

Guidelines currently used in many centers to determine prognosis after cardiac arrest are still based on the 2006 AAN Practice Parameters intended for patients not treated with TH despite recent evidence and new guidelines that advocate for delaying prognostication beyond 72 hours (31, 32, 39, 44, 45). Our results indicate that making WLST decisions at 72 hours postarrest could deprive as many as 36% of comatose survivors treated with TH of the opportunity to potentially achieve good neurological outcomes. Although we acknowledge that many of these patients will have a poor outcome, the possibility of a good outcome, no matter how small from this group, carries significant ethical concerns. Given the widespread practice of WLST at 72 hours, the number of those with potentially good outcomes may still be considerable. The magnitude of the potential number of patients who could achieve good functional status is unclear at this time, but our results indicate that there is room for improvement (41). This study is not designed to determine the optimal time to perform prognostication and WLST post-TH; however, it does suggest that 72 hours is an insufficient amount of time. Additionally, our findings are consistent with many other studies reporting a disproportionately high (> 80%) rate of death following WLST despite unclear data regarding appropriate timing and methods for prognostication. Our data also demonstrate that only a small proportion of OHCA survivors progress to brain death. The current uncertainties in the management of comatose-resuscitated cardiac arrest patients with TH or targeted temperature management are due, in good part, to our lack of understanding of the effects of the intervention; we feel that it is necessary for basic and translational science to help answer the many life-or-death questions we still face in this matter.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out in Hennepin County Medical Center; with statistical analysis done in Johns Hopkins Hospital and University, the article was written in collaboration across all institutions.

Dr. Gibbs is employed by the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Dr. Dhaliwal is employed by the Hennepin County Medical Center (Residency Training). Dr. Geocadin is employed by Johns Hopkins University, provided expert testimony for Medicolegal consulting, received support for development of educational presentations from University of California San Diego Continuing Medical Education and American Academy of Neurology Continuing Medical Education, and received support for travel from the American Heart Association and the Neurocritical Care Society. His institution received grant support from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

See also p. 2630.

For information regarding this article, rgeocad1@jhmi.edu

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee: Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2008;118:2452–2483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison LJ, Deakin CD, Morley PT, et al. Advanced Life Support Chapter Collaborators: Part 8: Advanced life support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S345–S421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan JP, Soar J. Postresuscitation care: Entering a new era. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:216–222. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283383dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geocadin RG, Peberdy MA, Lazar RM. Poor survival after cardiac arrest resuscitation: A self-fulfilling prophecy or biologic destiny? Crit Care Med. 2012;40:979–980. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182410146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson NS, Detre K, Bradley K, et al. Impact evaluation in resuscitation research: Discussion of clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:1053–1058. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198810000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewy GA, Kellum M. Advancing resuscitation science. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:221–227. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328352c702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Geocadin RG, et al. American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation: Primary outcomes for resuscitation science studies: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:2158–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182340239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, et al. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology: Practice parameter: Prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67:203–210. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227183.21314.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouwes A, Binnekade JM, Kuiper MA, et al. Prognosis of coma after therapeutic hypothermia: A prospective cohort study. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:206–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.22632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossetti AO, Oddo M, Logroscino G, et al. Prognostication after cardiac arrest and hypothermia: A prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:301–307. doi: 10.1002/ana.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Thenayan E, Savard M, Sharpe M, et al. Predictors of poor neurologic outcome after induced mild hypothermia following cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2008;71:1535–1537. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334205.81148.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rittenberger JC, Sangl J, Wheeler M, et al. Association between clinical examination and outcome after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1128–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wennervirta JE, Ermes MJ, Tiainen SM, et al. Hypothermia-treated cardiac arrest patients with good neurological outcome differ early in quantitative variables of EEG suppression and epileptiform activity. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2427–2435. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a0ff84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloostermans MC, van Meulen FB, Eertman CJ, et al. Continuous electroencephalography monitoring for early prediction of neurological outcome in postanoxic patients after cardiac arrest: A prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2867–2875. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b94f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crepeau AZ, Rabinstein AA, Fugate JE, et al. Continuous EEG in therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: Prognostic and clinical value. Neurology. 2013;80:339–344. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f089d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samaniego EA, Mlynash M, Caulfield AF, et al. Sedation confounds outcome prediction in cardiac arrest survivors treated with hypothermia. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:113–119. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronberg T, Rundgren M, Westhall E, et al. Neuron-specific enolase correlates with other prognostic markers after cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2011;77:623–630. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822a276d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bisschops LL, van Alfen N, Bons S, et al. Predictors of poor neurologic outcome in patients after cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia: A retrospective study. Resuscitation. 2011;82:696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi SP, Youn CS, Park KN, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia in adult cardiac arrest because of drowning. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fugate JE, Wijdicks EF, Mandrekar J, et al. Predictors of neurologic outcome in hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:907–914. doi: 10.1002/ana.22133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, et al. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; American Heart Association; European Resuscitation Council; Australian Resuscitation Council; New Zealand Resuscitation Council; Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada; InterAmerican Heart Foundation; Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa; ILCOR Task Force on Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Outcomes: Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: Update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa) Circulation. 2004;110:3385–3397. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147236.85306.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial II Study Group. A randomized clinical trial of calcium entry blocker administration to comatose survivors of cardiac arrest design, methods, and patient characteristics. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12:525–545. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(91)90011-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps R, Dumas F, Maynard C, et al. Cerebral Performance Category and long-term prognosis following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1252–1257. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults. Neurology. 1995;45:1012–1014. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fugate JE, Wijdicks EF, White RD, et al. Does therapeutic hypothermia affect time to awakening in cardiac arrest survivors? Neurology. 2011;77:1346–1350. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318231527d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronberg T, Horn J, Kuiper MA, et al. A structured approach to neurologic prognostication in clinical cardiac arrest trials. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:45. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunde K, Dunlop O, Rostrup M, et al. Determination of prognosis after cardiac arrest may be more difficult after introduction of therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2006;69:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossestreuer AV, Abella BS, Leary M, et al. Time to awakening and neurologic outcome in therapeutic hypothermia-treated cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1741–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold B, Puertas L, Davis SP, et al. Awakening after cardiac arrest and post resuscitation hypothermia: Are we pulling the plug too early? Resuscitation. 2014;85:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds JC, Rittenberger JC, Callaway CW. Methylphenidate and amantadine to stimulate reawakening in comatose patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:818–824. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson DK, Zive D, Daya M, et al. The impact of early do not resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cronberg T, Wise MP, Nielsen N. Mild-induced hypothermia and neuroprognostication following cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2537–2538. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825458f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouwes A, Binnekade JM, Verbaan BW, et al. Predictive value of neurological examination for early cortical responses to somatosensory evoked potentials in patients with postanoxic coma. J Neurol. 2012;259:537–541. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6224-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geocadin RG, Buitrago MM, Torbey MT, et al. Neurologic prognosis and withdrawal of life support after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2006;67:105–108. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223335.86166.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geocadin RG, Kaplan PW. The effect of therapeutic hypothermia on prognostication. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perman SM, Kirkpatrick JN, Reitsma AM, et al. Timing of neuroprognostication in postcardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:719–724. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182372f93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. TTM Trial Investigators: Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2197–2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell K, Grill E, Klein AM, et al. Rehabilitation outcome of anoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy survivors with prolonged disorders of consciousness. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1409–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laver S, Farrow C, Turner D, et al. Mode of death after admission to an intensive care unit following cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2126–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2425-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dragancea I, Rundgren M, Englund E, et al. The influence of induced hypothermia and delayed prognostication on the mode of death after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cronberg T, Brizzi M, Liedholm LJ, et al. Neurological prognostication after cardiac arrest—Recommendations from the Swedish Resuscitation Council. Resuscitation. 2013;84:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandroni C, Cavallaro F, Callaway CW, et al. Predictors of poor neurological outcome in adult comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: Patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1324–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]