Abstract

Cross-species viral transmission subjects parent and progeny alphaviruses to differential post-translational processing of viral envelope glycoproteins. Alphavirus biogenesis has been extensively studied, and the Semliki Forest virus E1 and E2 glycoproteins have been shown to exhibit differing degrees of processing of N-linked glycans. However the composition of these glycans, including that arising from different host cells, has not been determined. Here we determined the chemical composition of the glycans from the prototypic alphavirus, Semliki Forest virus, propagated in both arthropod and rodent cell lines, by using ion-mobility mass spectrometry and collision-induced dissociation analysis. We observe that both the membrane-proximal E1 fusion glycoprotein and the protruding E2 attachment glycoprotein display heterogeneous glycosylation that contains N-linked glycans exhibiting both limited and extensive processing. However, E1 contained predominantly highly processed glycans dependent on the host cell, with rodent and mosquito-derived E1 exhibiting complex-type and paucimannose-type glycosylation, respectively. In contrast, the protruding E2 attachment glycoprotein primarily contained conserved under-processed oligomannose-type structures when produced in both rodent and mosquito cell lines. It is likely that glycan processing of E2 is structurally restricted by steric-hindrance imposed by local viral protein structure. This contrasts E1, which presents glycans characteristic of the host cell and is accessible to enzymes. We integrated our findings with previous cryo-electron microscopy and crystallographic analyses to produce a detailed model of the glycosylated mature virion surface. Taken together, these data reveal the degree to which virally encoded protein structure and cellular processing enzymes shape the virion glycome during interspecies transmission of Semliki Forest virus.

Keywords: glycoprotein, virus, alphavirus, structure, glycosylation

Introduction

Semliki Forest virus (SFV) is a prototypic alphavirus within the Togaviridae family and was first isolated in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in Uganda in 1944.1 Although SFV infection only causes mild febrile illness in humans, it is highly pathogenic in rodents and has become a model system for investigating viral encephalitis2 caused by other neurotropic alphaviruses such as Sindbis virus, Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

The positive-sense, single-stranded RNA alphavirus genome encodes nine proteins, three of which are structural and encoded in the second of two open reading frames. In the mature particle, the capsid protein C forms an icosahedral shell (triangulation T = 4) that encapsulates the viral RNA and is surrounded by a lipid bilayer.3,4 Two membrane-bound glycoproteins, E1 and E2, form an outer icosahedral shell (triangulation T = 4)4,5 and are responsible for host cell fusion and attachment, respectively.6 E1 and E2 are generated by proteolytic cleavage of polyprotein precursor via the E1–p62 intermediate.7

Alphaviruses assemble in the plasma membrane, where the cytoplasmic tail of the E2 glycoprotein interacts with the RNA-containing capsid, leading to budding of mature virions.8 Co-translational formation of the E1–p62 heterodimer is necessary for proper folding.7 The E1–p62 heterodimer forms concomitantly to protein folding in the ER, and the glycans are initially processed in the context of this structure.7 The initial formation of single trimeric viral spikes, (E1–p62)3, is thought to occur in this stage.9 Proteolytic cleavage by furin in the trans-Golgi network is required to cleave p62 into E2 and a third glycoprotein, E3.10 This cleavage primes E1 for fusion and enables the formation of trimers of E1/E2 heterodimers on infectious virus particle.4

The E1 glycoprotein forms a class-II fusion glycoprotein fold11 with a sequence-internal hydrophobic fusion peptide that is buried within the E1–E2 interface.12 Upon endosomal acidification during clathrin-mediated host cell entry, E1 undergoes conformational rearrangements into fusogenic homotrimers, which merge the virion and endosomal membranes.13−15 The structure of the E2 glycoprotein was revealed through crystallographic analysis of the E1–E2 complex from CHIKV.12 E2 is composed of three immunoglobulin-like domains and forms a ∼2500 Å2 protein–protein contact surface with E1.12,16

Infectious particles are targeted by the host antibody response, which is directed predominantly to E2.17 This is consistent with E2 being more membrane distal and solvent-exposed than E1.12,18−20 The capacity of alphaviruses to infect a wide range of species is suggested to be, in large part, due to the ability of the E2 glycoprotein to attach to and interact with multiple cellular receptors.21

Alphaviral glycosylation is an important determinant of cellular tropism and virulence,22−25 and the composition of alphavirion glycans derived from mammalian cell lines has been the subject of extensive study.26−36 The alphaviral E1 and E2 glycoproteins are post-translationally modified with N-linked glycosylation. For example, SFV has one N-linked sequon on E1 and two on E2.37 Across alphaviruses, it has been generally observed that glycans from the E1 fusion glycoprotein derived from mammalian cell lines are highly processed and composed of complex-type glycosylation. Conversely, glycans from the E2 glycoprotein exhibit endoglycosidase H (Endo H) sensitivity and are, therefore, composed of hybrid- or oligomannose-type structures. For example, across the eastern equine encephalitis alphaviruses, E1 exhibits complex-type glycosylation, while E2 has a high level of Endo H-sensitive structures.32 Similarly, Barmah Forest virus exhibits predominantly complex-type glycosylation on E1 but has no glycans on E2.29,30 In Sindbis virus, E1 primarily exhibited complex-type glycosylation, while E2 exhibited a greater degree of oligomannose-type glycosylation.31,36 Importantly, the location of the N-linked glycan sequons is not well-conserved across the alphaviruses, and the precise environment of a glycan can heavily influence processing.38

The identification of less-processed structures has implicated C-type lectins, DC-SIGN and L-SIGN, as putative mammalian attachment receptors for alphaviruses.22 Host species have a significant impact on glycosylation processing, however, which may introduce or eliminate these lectin-binding motifs.39 For example, SFV derived from mosquito C6/36 cells exhibited Endo D-sensitive paucimannose structures on E1, while E2 was almost entirely sensitive to Endo H.24,26 The formation of paucimannose structures necessitates extensive Golgi-mediated processing for biosynthesis.33,34 These structures are therefore biosynthetically analogous to the processed complex-type glycosylation of mammals.

It has been long appreciated that both cellular (e.g., cell type) and viral factors (e.g., protein-directed glycosylation) play an important role in determining the chemical composition of glycans.24,38,40 We selected the prototypic alphavirus, SFV, to investigate the compositional variation of glycosylation through a side-by-side comparison of virus derived from both arthropod and rodent cell lines. We performed mass spectrometric analysis of the glycans from SFV purified from both types of cell lines using ion-mobility mass spectrometry and collision-induced dissociation analysis. We observe that in contrast with the fully processed E1 glycoprotein, E2 preserves under-processed oligomannose-type structures regardless of host species. By integrating this analysis with known crystallographic and electron microscopy data, we rationalize these observations and propose that glycan processing on E2 is restrained by local steric-hindrance, whereas the E1 glycan is accessible to enzymes despite being located at the base of the multimeric viral spike. Our mass spectrometric study comprises the first structural and compositional analysis of alphavirus N-linked glycosylation. These data reveal the consequence of steric protection and cellular processing enzymes on the composition of the virion glycome during interspecies transmission of SFV.

Material and Methods

Virus Preparation

BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney-21) cells were maintained in Glasgow minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% tryptose phosphate broth and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. C6/36 cells were maintained in Schneider’s Drosophila medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 2% glutamine and grown at 28 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Wild-type SFV (strain pSP6-SFV4)41 was kindly provided by Prof. M. Kielian (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY) and propagated in BHK-21 cells to determine virus titer. C6/36 cells and BHK-21 were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1 and 0.1, respectively. Media containing secreted SFV were collected ∼136 h following infection in C6/36 cells and ∼22 h after infection in BHK-21 cells, similar to previous methods.42 Virion purification was based on that previously described for alphaviruses.43 Supernatants were cleared from cell debris by low-speed centrifugation, and viral particles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation. For SFV isolation from BHK-21 cells, an additional sucrose density gradient centrifugation step was added. Virus purity and endoglycosidase F1 (Endo F1) susceptibility was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis. Endo F1 was expressed as a fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase (GST) and has been previously described by Grueninger-Leitch et al.44

Electron Microscopy

To confirm sample integrity, we vitrified purified SFV from BHK cells by rapid plunge-freezing on “C-flat” electron microscopy grids (Protochips, Raleigh, NC) into a mixture of liquid ethane (37%) and propane (63%).45 Electron cryomicroscopy was performed using a 300 kV “Polara” transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands) operated at a temperature of ∼80 K. Images of SFV were taken at −4 μm defocus using a charge-coupled device camera (Ultrascan 4000SP; Gatan, Pleasanton, CA) at a nominal magnification of ×93 000, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 0.24 nm with a dose of ∼12 e–/Å2.

Glycan Isolation

Oligosaccharides were released from SFV E1 and E2 glycoproteins with peptide-N-glycosidase F (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) from Coomassie blue-stained PAGE gels, as previously described.46 Gel bands were excised, washed five times alternatively with acetonitrile and deionized water, and rehydrated with 30 units of aqueous PNGase F solution. After incubation for 12 h at 37 °C, enzymatically released glycans were eluted with water.

Ion-Mobility Mass Spectrometry

Glycan samples were diluted with 5 μL of water. A 1 μL aliquot was cleaned with a Nafion membrane47 and diluted with water (4 μL), methanol (5 μL), and 0.1 M ammonium phosphate (0.5 μL, to maximize formation of [M+H2PO4]− ions) and centrifuged at 9500g for 1 min. Electrospray (ESI) and ion mobility experiments were carried out in negative ion mode with a Waters Synapt G2 traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometer (Waters MS-technologies, Manchester, U.K.)48 fitted with an ESI ion source. Samples were infused through Waters thin-wall nanospray capillaries. The ESI capillary voltage was 1.2 kV, the cone voltage was 80 V, and the ion source temperature was maintained at 80 °C. The T-wave velocity and peak height voltages were 450 m/sec and 40 V, respectively. Instrument calibration was performed with released N-linked glycans from bovine fetuin. The T-wave mobility cell (nitrogen) was operated at a pressure of 0.55 mbar. Fragmentation was performed after mobility separation in the transfer cell with argon as the collision gas. Data acquisition and processing were carried out using the Waters Driftscope (version 2.1) software and MassLynx (version 4.1). Analysis of MS data was performed using the previously described methods49−51 by comparison with spectra of well-characterized N-linked glycans from ribonuclease B,52 bovine fetuin,53 and human transferrin.54

Model Construction

A model of N-linked glycan presentation on the alphavirus surface was created using the crystal structure of the CHIKV E1–E2 envelope glycoprotein complex fit into the Sindbis virus cryo-EM map (PDB accession number 2XFB(12)). N-linked glycans, representative of those observed on SFV when produced in BHK and C6/36 cells (see Results and Discussion), were modeled onto the N-linked carbohydrate attachment sites Asn141 on E1 as well as Asn200 and Asn262 on E2. Figures were illustrated using PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Nomenclature

The symbolic representation of glycans follows that of Harvey et al.55 with residues in both the schematic diagrams and molecular graphics following the color scheme of the Centre for Functional Glycomics, as previously implemented.56,57 A key is given in Figure 2. Thus, ions retaining charge on the nonreducing terminus are named “A” (cross-ring), “B”, and “C” (glycosidic) with corresponding ions from the reducing terminus named X, Y, and Z. Subscript numbers define the bonds cleaved in the glycan sequence. For fragmentation analysis, we applied an extension of the Domon and Costello nomenclature by Harvey et al.,58,59 whereby the subscript number for the reducing terminal GlcNAc residue is replaced by “R” and the number from the adjacent GlcNAc is replaced by “R-1”. This nomenclature describes fragmentations of different glycan cores to avoid confusion by the subscript number changing in response to different antenna lengths. Bonds cleaved in the cross-ring cleavage reactions are indicated by superscript numbers.

Figure 2.

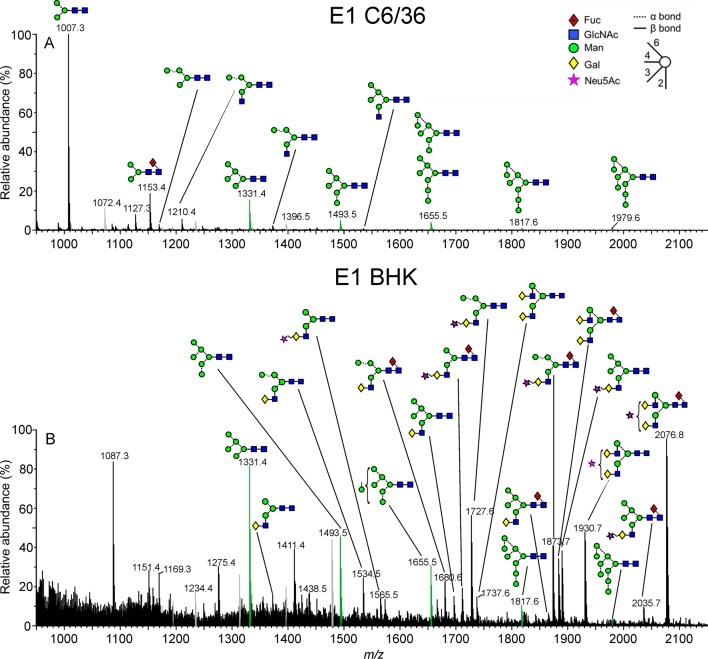

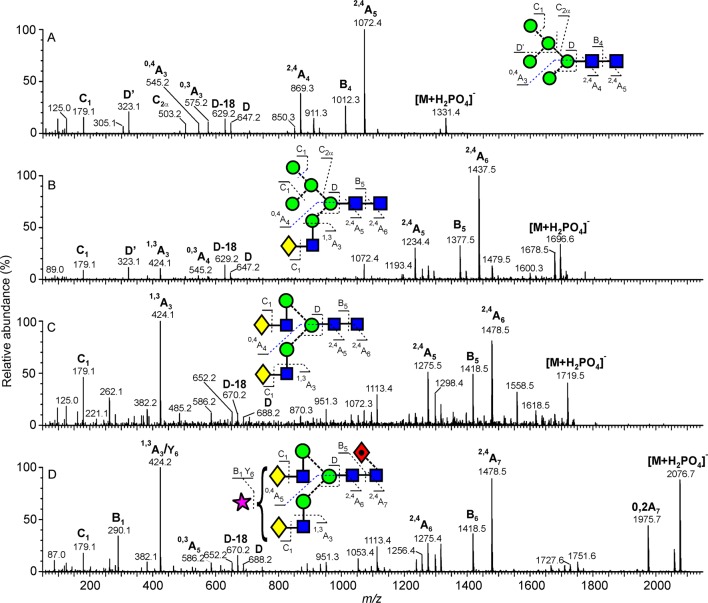

Mobility-extracted singly negatively charged N-glycan ions from the E1 glycoproteins from the mosquito (spectrum A) and rodent cell lines (spectrum B). A key to the symbols used for the glycan structures is displayed in the upper right-hand corner of panel A. The linkages are shown by the angle of the lines connecting the symbols (| = 2-link, / = 3-link, – = 4-link, and \ = 6-link). α-Bonds are shown with broken lines and β-bonds are shown with full lines. Full details are given in ref (80). Oligomannose-type glycans are highlighted in green, and fragment ions are shown in gray.

Results and Discussion

The glycosylation of alphavirus has been extensively studied, and the SFV E1 and E2 glycoproteins have been shown to exhibit differing degrees of biosynthetic processing of N-linked glycans. However, the composition of these glycans, including that arising from different host cells, has not been determined. We have applied ion-mobility mass spectrometry to define the virion glycome in two principal host species, rodent and mosquito.

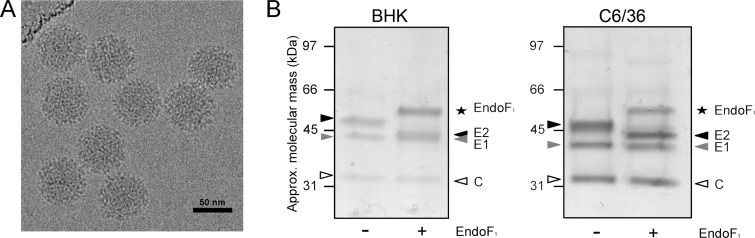

Preparation of Rodent and Mosquito SFV Glycoforms

For virus propagation and purification, BHK and mosquito C6/36 cells were infected with SFV. These cell lines were chosen because the natural hosts of SFV include mosquitoes and rodents.1,2,60 To purify and isolate virions, we subjected media from infected cells to ultracentrifugation. We verified that our production and purification system was generating mature intact particles by electron microscopy and SDS-PAGE analysis (Figure 1). The electron micrographs revealed uniform virions consistent with their T = 4 icosahedral symmetry11 (Figure 1A). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed three discrete bands consistent with E1, E2, and the capsid protein (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Sample preparation of SFV from BHK and C6/36 cell lines. (A) Electron cryomicroscopy image of SFV virions, purified from BHK cells, taken at −4 μm defocus. Scale bar: 50 nm. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of SFV purified from BHK (lanes 1 and 2) and C6/36 cells (lanes 3 and 4). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue, and the protein bands correspond to the SFV structural proteins: capsid (labeled “C”; white triangle), E1 (gray triangle), and E2 (black triangle) proteins. BHK- and C6/36-derived SFV were treated with endoglycosidase F1 (Endo F1; star) in lanes 2 and 4, respectively. Endo F1 was expressed as a fusion protein with GST, as previously reported.44

E1 and E2 Differ in Sensitivity to Endoglycosidase F1

Following previous investigations of alphaviral glycosylation,26−36 we studied the sensitivity of the virion-associated E1 and E2 glycans to Endo F1 digestion (Figure 1B). The Endo F1 used in this study has been previously described by Grueninger-Leitch et al.44 Endo F1 hydrolyzes the di-N-acetylchitobiose core (GlcNAcβ1→4GlcNAc) of oligomannose-type and hybrid-type glycans.61 Complex-type glycans are insensitive to Endo F1.61 E1, regardless of being derived from BHK or C6/36 cells, was largely insensitive to Endo F1 (Figure 1B) and is therefore largely devoid of oligomannose- and hybrid-type glycosylation. In contrast, E2 exhibited a reduction in apparent molecular mass by several kilodaltons (Figure 1B), indicating the presence of oligomannose- or hybrid-type glycan structures. These results are consistent with the role of E2 in C-type lectin binding22 as well as with previously described radiolabeling experiments, which revealed differential processing of E1 and E2 in C6/36 cells.26 While E2 from both cell lines migrated similarly, E1 from BHK cells was measurably larger in apparent molecular mass than E1 from C6/36 cells (Figure 1B). These results suggest that N-linked post-translational modifications are more substantial in BHK cells than in C6/36 cells. Our findings support the conclusion that SFV exhibits glycosylation directed by viral and cellular factors on E2 and E1 glycoproteins, respectively.

Analysis of N-Linked Glycans from Intact Virions by Ion Mobility MS

To identify the chemical composition of the N-linked glycans from E1 and E2 of SFV, we performed mass spectrometric analysis of enzymatically released glycans. Because low-abundance biological samples often pose challenges to detailed characterization,51 we chose to employ ion mobility MS. This technique enables the separation of glycan ions that are otherwise obscured by contamination arising during sample preparation.51 We hypothesized that this method would enable analysis of glycans from intact virions at sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, which hitherto has been limited.

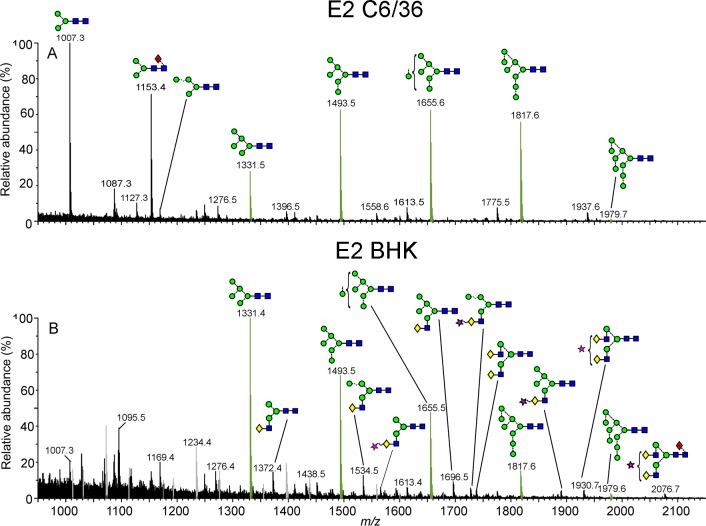

For ion mobility MS, E1 and E2 glycans from both C6/36 and BHK cells were released by PNGase F exoglycosidase treatment. This treatment releases all N-linked glycans except for those with core α1→3-fucosylation.63 The resulting spectra of the extracted glycans from E1 and E2 are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively, and reveal the utility of ion mobility MS for studying low abundance samples.

Figure 3.

Mobility-extracted singly negatively charged N-glycan ions from the E2 glycoproteins from the mosquito (spectrum A) and rodent cell lines (spectrum B). Symbols used for the glycan structures are as defined in Figure 2. Oligomannose-type glycans are highlighted in green, and fragment ions are shown in gray.

Cell-Line-Dependent Processing of E1

Consistent with the protein migration shift observed in Figure 1B, ion mobility MS revealed that the molecular mass of E1 glycans produced in the rodent cells (BHK) was considerably larger than E1 glycans produced in the mosquito cells (C6/36) (Figure 2). The spectrum of mosquito cell-derived E1 glycans was dominated by paucimannose structures and minor fucosylated derivates, such as Man3GlcNAc2 and Man3GlcNAc2Fuc, respectively (Figure 2A). This is consistent with extensive glycan processing in the mosquito Golgi apparatus.64 In this insect system, glycans are trapped in the paucimannose state by hexosaminidase activity, which removes the GnT I-mediated GlcNAc necessary for the action of other transferases.64 In contrast, the spectrum of E1 glycans derived from the rodent cell line exhibited considerable complexity, dominated by biantennary glycans exhibiting variable occupancy of terminal galactose and sialic acid (Figure 2B). This observation supports a model whereby the E1 glycan is fully accessible to enzymatic processing. Hybrid-type glycans are also present together with a minor population of smaller oligomannose-type glycans. Importantly, the relative population of oligomannose-type glycans matched that observed in the spectrum of mosquito-derived E1 with Man5GlcNAc2 > Man6GlcNAc2 > Man7GlcNAc2. This comparable distribution is suggestive of conserved processing between systems. We suggest this is likely to arise from similar glycan presentation and accessibility to biosynthetic enzymes in the ER.

Virion-Directed Glycosylation of E2

Comparison of the spectra of E2 glycans from mosquito and rodent cell lines revealed substantial convergence of composition despite the considerable variation in the processing machinery of the two systems (Figure 3). Both spectra were dominated by the full oligomannose series, Man5–9GlcNAc2, with only a minor population of glycans exhibiting Golgi processing, characteristic of that primarily observed on E1 glycans. In contrast with the conserved distribution of oligomannose-type structures in E1 (Figure 3), the distribution of oligomannose-type structures differed between rodent and mosquito-derived E2. In mosquito-derived E2, the Man9GlcNAc2 glycan was most abundant with decreasing levels down the series to Man5GlcNAc2. Surprisingly, this trend was reversed in the rodent system. This reversal indicates that while E2 glycans are largely protected from processing following the calnexin/calreticulin folding checkpoint, the efficacy of the mosquito α-mannosidases differs from that of the rodent system. We would not expect the physical presentation of these conserved, early glycans to differ between systems, and these differences are therefore likely driven by dissimilarities in specific activity of cell resident α-mannosidases or in transit time. The variance in E2 oligomannose processing between cell lines may also indicate that the conservation of the processing of the minor oligomannose series observed on E1 is somewhat coincidental. Given the functional importance of oligomannose-type glycans,22 it would be valuable to investigate the stability of α-mannosidase processing in related alphaviruses. It should also be noted that the temperature difference between insect and mammalian viral production can influence viral architecture, and this may influence glycan processing.65,66 Finally, E3 is shed in various stages during alphavirus biogenesis,4 and the influence of E3 on glycan processing is unknown.

Glycan Assignments by MS/MS

Ion mobility combined with MS/MS analysis involves a highly sensitive ion-extraction technique, able to separate low abundance glycan ions from contaminants, with the generation of fragmentation fingerprints characteristic of particular substructures within glycans. This also enables accurate assignments of isomers, for example, the effective discrimination between isobaric complex and hybrid-type structures on the virion surface.

The glycan assignments previously discussed were based on detailed MS/MS fragmentation analysis following mobility separation (Figures 4 and 5). The mass of each glycan gave the constituent monosaccharide composition in terms of isobaric residues such as hexose and N-acetylhexose (HexNAc). Structures of the di-N-acetylchitobiose core, the 6- and 3-antennae, isomers (when present), and the complex biantennary glycans were assigned based on combination of the parent molecular ion mass and the pattern of fragmentation ions produced by collision-induced dissociation. This assignment process is described later.

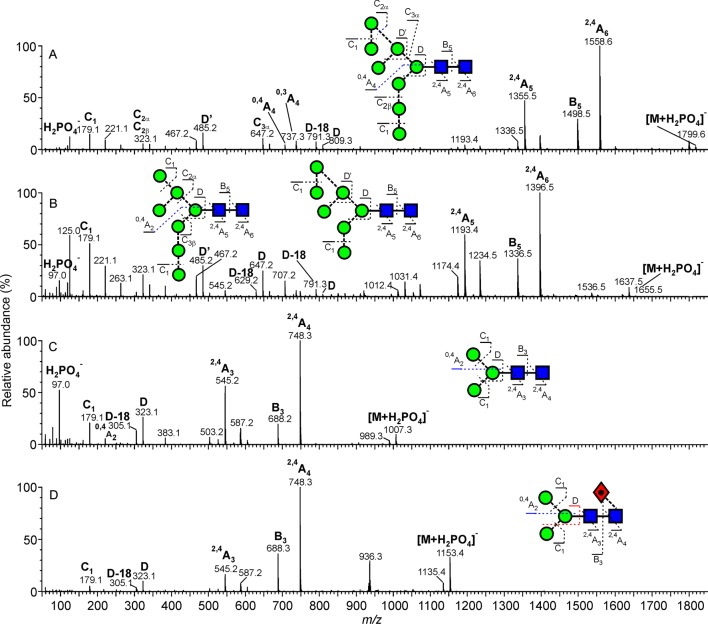

Figure 4.

Examples of mobility-extracted, negative ion CID (transfer region) spectra of N-glycans from SFV derived from a mosquito cell line. (A) Man8GlcNAc2, (B) Man7GlcNAc2, (C) Man3GlcNAc2, and (D) fucosylated Man3GlcNAc2. Symbols used for the glycan structures are as defined in Figure 2. Ion nomenclature follows that proposed by Domon and Costello58 with spectral interpretation as described by Harvey et al.49,50

Figure 5.

Examples of mobility-extracted, negative ion CID (transfer region) spectra of N-glycans from SFV derived from rodent cell lines. (A) Man5GlcNAc2, (B) hybrid-type glycan (Man5GlcNAc3Gal1), (C) biantennary glycan (Man3GlcNAc4Gal2), and (D) sialylated biantennary glycan (Man3GlcNAc4Gal2Fuc1Neu5Ac1).

The di-N-acetylchitobiose core region of all glycans was characterized by the production of abundant 2,4AR, BR-1, and 2,4AR-1 ions. (See the Nomenclature section.) For example, these ions correspond to peaks at m/z 1072, 1012, and 869 in the spectrum of Man5GlcNAc2 (Figure 5A). The phosphate adducts of the glycans resulted in the 2,4AR ion appearing at 259 mass units below that of the molecular ([M+H2PO4]−) ion. A loss of 405 mass units, as observed in the spectrum of the fucose-containing Man3GlcNAc2Fuc1 (Figure 4D), reveals that the fucose is located at the six-position of the reducing-terminal GlcNAc. (Note that the proton from the 3-OH group is lost when forming this ion, leaving the six-position as the only remaining position for substitution.) Figure 4C shows the spectrum of the corresponding unfucosylated glycan.

The composition of the 6-antenna, and by difference the 3-antenna, was defined by analysis of the D and D-18 ions (these ions are formed by the formal loss of the di-N-acetylchitobiose core 3-antenna) and 0,3AR-2 and 0,4AR-2 ions from the core branching mannose residue. These ions appear at m/z 647, 629, 575, and 545, respectively, in Man5GlcNAc2 (Figure 5A) and at m/z 809, 791, 737, and 707 in that of Man8GlcNAc2 (Figure 4A), where there is an additional mannose residue in the 6-antenna. Localization of this mannose to the 6-branch of this antenna was facilitated by identification of the abundant ion at m/z 485, termed D′. Where isomers were present, as in the case of Man7GlcNAc2 (Figure 4B), two groups of ions appeared depending on the number of mannose residues in the 6-antenna. In this spectrum, ions at m/z 647, 629, and 545 and at m/z 809, 791, 737, and 707, respectively, revealed the presence of three and four mannose residues in the 6-antenna. The presence of these ions also informed on the composition of hybrid-type glycans in the BHK-derived samples (Figure 5B,C). For example, ions at m/z 647, 629, 575, and 545 in the spectrum of Man5Gal1GlcNAc3 (Figure 5B) revealed glycans at the 6-antenna identical to those observed in the high-mannose glycan, Man5GlcNAc2 (Figure 5A). An additional feature of hybrid-type glycans (Figure 5B,C) is the presence of the 1,3A3 ion at m/z 424, which defines a Gal-GlcNAc composition at the 3-antenna. The single C1 ion at m/z 179 in the glycoforms derived from both C6/36 and BHK cells (Figures 4 and 5) confirms hexose as the terminating residue for all antennae.

Structures of the complex biantennary glycans, such as those depicted in Figure 5C,D, were similarly determined by characteristic fragmentation ions. D and D-18 ions were located at m/z 688 and 670, respectively, while the single 1,3A3 ion at m/z 424 confirmed the structure of the Gal-GlcNAc antennae. Termination of these fragments with galactose is supported by identification of the C1 ion at m/z 179. Substitution of this glycan with sialic acid (Figure 5D) gave a spectrum similar to that of the neutral glycan. The 2,4AR, BR-1, and 2,4AR-1 ions were formed with concomitant loss of the sialic acid moiety, and their mass at m/z 1478, 1418, and 1275 confirmed the presence of the core fucose. Confirmation of the sialic acid (Neu5Ac) residue was made by the B1 ion at m/z 290, and the absence of the ion at m/z 306 showed that this residue was predominantly α2→3 linked.67

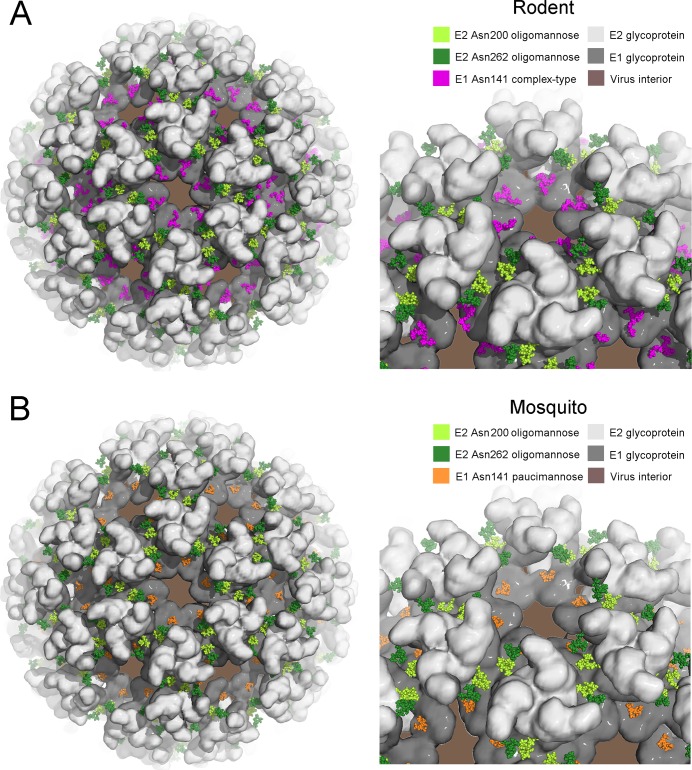

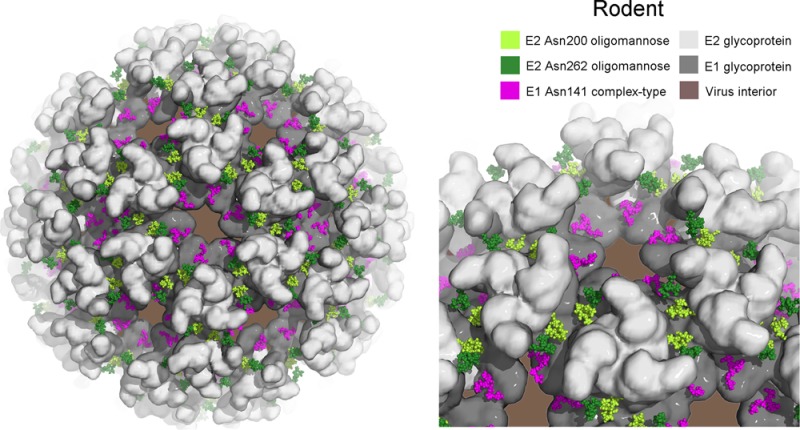

Distribution of Glycans Across the Alphaviral Surface

Our analysis supports the conclusion that the glycans of the E2 glycoprotein are largely resistant to enzymatic processing. There are many examples where the local environment of glycans limits processing in the ER and Golgi apparatus in both mammalian and viral glycoproteins.38 One extreme example is the processing of the envelope attachment glycoprotein gp120 from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1).68 The density of N-linked glycans is sufficient to induce a minimally processed “mannose patch” of oligomannose-type glycans on intact virions.69−71 More commonly, protein–carbohydrate packing can also disrupt the processing of N-linked glycosylation.38,72,73

The presence of oligomannose-type glycans on SFV can influence cellular tropism and virulence24 and suggests that there may have been evolutionary pressure on the virus to control the processing of host glycosylation by indirectly altering the proteinous environment around the glycans. When considering the structural influences on glycan processing, it is important to evaluate the presentation of glycans to α-mannosidases both from initial folding in the ER and Golgi transit. In SFV biosynthesis, initially isolated E1–p62 heterodimers are formed in the ER and are then thought to trimerize.7 The trimers are transported from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and further toward the plasma membrane. During later stages of transport, (E1–p62)3 complexes are thought to form higher order assemblies similar to those observed in the virion.9

To rationalize the structure of the glycans on the mature virion surface, we constructed a model of the mature (E1–E2)3 viral spike from the structure of the related alphaviral CHIKV glycoproteins. Glycans were modeled onto the E1 and E2 glycoprotein using the crystallographic coordinates reported for a sialylated complex-type glycan74 and an oligomannose-type glycan,75 respectively. A model for the virion surface was further constructed by using the glycosylated CHIKV E1–E2 structure fitted into the electron microscopy map of Sindbis virus12 for SFV produced in both rodent (Figure 6A) and mosquito (Figure 6B) cells.

Figure 6.

Models of the glycosylated alphavirus surface as derived from rodent (A) and mosquito (B) cells. The crystal structure of the CHKV E1–E2 envelope glycoprotein complex was fitted into the Sindbis virus cryo-EM map (PDB accession number 2XFB).12 E1 and E2 are shown in a surface representation in dark gray and light gray, respectively. Oligomannose-type glycans, presented by E2 at Asn200 and Asn262, are shown as light- and dark-green spheres, respectively (Man9GlcNAc2, from PDB accession code 2WAH(75)). At Asn141, glycan structures are modeled as complex-type glycans for rodent-derived alphavirus (panel A; pink spheres, from PDB accession code 4BYH(74)) and paucimannose-type for mosquito-derived alphavirus (panel B; orange spheres, from PDB accession code 2WAH).

Despite being located in the crevices created by the virion spike, the E1 glycan is fully accessible both in isolated (E1–E2)3 complexes, which are likely to be observed in the Golgi apparatus and ER, and in the mature virion through the hexagonal space formed between protomers (Figure 6). This presentation is entirely consistent with host-dependent glycosylation in rodent (Figure 6A) and mosquito (Figure 6B) cellular secretion pathways, whereby glycosylhydrolases and glycosyltransferases help to determine glycan composition. In contrast with E1, the E2 glycans are more membrane-distal and are located on the side of the viral spike, which is presumably sufficient to limit α-mannosidase processing in the ER and early Golgi (Figure 6). In the mature virion, the glycans are driven into close proximity to the protein surface of opposing protomers of the trimer and yet are accessible for cell attachment by DC-SIGN recognition.22

Conclusions

Our study provides a glycomic analysis of the N-linked glycans displayed on the major glycoproteins from SFV, a prototypic alphavirus. Consistent with early electrophoretic analyses of alphaviral glycans,26−36 we show that E1 and E2 display predominantly complex- and oligomannose-type glycosylation, respectively. These results indicate that in contrast with E1, which presents glycans characteristic of the host species, the glycan processing of E2 is particularly restricted. Such compositional differences may be attributed to localized steric-controlled hindrance of enzymatic processing imposed by the virus.

The presence of both complex- and oligomannose-type glycosylation on the envelope glycoproteins of membranous viruses is an emerging theme in viral glycomics. As an extreme, the oligomannose-type glycans on gp12069 of HIV-1 are thought to arise by local steric constraints imposed by both glycan–glycan clustering and glycan–protein interactions.70 Similar to SFV,22−25 precise glycan processing influences the cellular tropism of HIV-1.76 In addition, broadly neutralizing antibodies that recognize mixed glycan/protein epitopes have emerged as guides to HIV vaccine design and even as potential antivirals.77−79 To this end, our analysis of SFV virion glycosylation assists in the definition of the alphaviral antigenic surface. Defining how the host modulates alphavirion glycosylation will assist in understanding how the mammalian immune system differs in the recognition of insect- and mammalian-derived particles.

We anticipate that the sensitive ion mobility methodologies adopted in this study will enable the precise analysis of glycans from membrane viruses where low abundance has impeded traditional mass spectrometric approaches. The resolution of our method further allows us to explore the range of structures displayed by each of the alphaviral glycoproteins. We show that specific glycan types are not exclusive to either glycoprotein and observe that both proteins display a full range of glycan structures, ranging from oligomannose series with little biosynthetic processing to fully processed complex-type glycans. Such compositional variation, which is either imposed by the virus or the host, is likely to influence host-cell tropism and immunological responses to alphavirus infection.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to the late Dr. Chris Scanlan. We thank Prof. Raymond Dwek FRS, Prof. E. Yvonne Jones, and Prof. David Stuart FRS for helpful discussions. C6/36 mosquito cells and BHK cells were kindly provided by Prof. Richard Elliott (University of Glasgow, U.K.). We thank the Wellcome Trust (grant number 090532/Z/09/Z; 089026/Z/09/Z to T.A.B.), Academy of Finland (grant number 130750, 218080 to J.T.H.), and Medical Research Council (MR/L009528/1 to T.A.B.) for funding. The laboratory of M.C. is supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and CHAVI-ID. M.C. is a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Smithburn K. C.; Haddow A. J.; Mahaffy A. F. A neurotropic virus isolated from Aedes mosquitoes caught in the Semliki forest. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1946, 26, 189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins G. J.; Sheahan B. J.; Dimmock N. J. Semliki Forest virus infection of mice: a model for genetic and molecular analysis of viral pathogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 1985, 66Pt 3395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S. D.; Berriman J. A.; Butcher S. J.; Gowen B. E. Low pH induces swiveling of the glycoprotein heterodimers in the Semliki Forest virus spike complex. Cell 1995, 81, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaney M. C.; Duquerroy S.; Rey F. A. Alphavirus structure: activation for entry at the target cell surface. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venien-Bryan C.; Fuller S. D. The organization of the spike complex of Semliki Forest virus. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 236, 572–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J. H.; Strauss E. G. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 58, 491–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H.; Barth B. U.; Ekstrom M.; Garoff H. Oligomerization-dependent folding of the membrane fusion protein of Semliki Forest virus. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 9654–9663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. E.; Kielian M. Semliki forest virus budding: assay, mechanisms, and cholesterol requirement. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 7708–7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soonsawad P.; et al. Structural evidence of glycoprotein assembly in cellular membrane compartments prior to Alphavirus budding. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11145–11151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Fugere M.; Day R.; Kielian M. Furin processing and proteolytic activation of Semliki Forest virus. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2981–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescar J.; et al. The Fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: an icosahedral assembly primed for fusogenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell 2001, 105, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss J. E.; et al. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature 2010, 468, 709–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian M.; Helenius A. pH-induced alterations in the fusogenic spike protein of Semliki Forest virus. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 101, 2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J. M.; Bron R.; Wilschut J.; Garoff H. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus involves homotrimers of the fusion protein. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 7309–7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons D. L.; et al. Conformational change and protein-protein interactions of the fusion protein of Semliki Forest virus. Nature 2004, 427, 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E.; Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R. J. In Fields Virology; Knipe D.M., Ed.; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, 2007; Vol. 1, pp 1001–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; et al. 4.4 A cryo-EM structure of an enveloped alphavirus Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. The EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3854–3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuchenko V. A.; et al. The structure of barmah forest virus as revealed by cryo-electron microscopy at a 6-angstrom resolution has detailed transmembrane protein architecture and interactions. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 9327–9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.; et al. Molecular links between the E2 envelope glycoprotein and nucleocapsid core in Sindbis virus. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 414, 442–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. S.; Schmaljohn A. L.; Kuhn R. J.; Strauss J. H. Antiidiotypic antibodies as probes for the Sindbis virus receptor. Virology 1991, 181, 694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra W. B.; Nangle E. M.; Smith M. S.; Yurochko A. D.; Ryman K. D. DC-SIGN and L-SIGN can act as attachment receptors for alphaviruses and distinguish between mosquito cell- and mammalian cell-derived viruses. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12022–12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabman R. S.; et al. Differential induction of type I interferon responses in myeloid dendritic cells by mosquito and mammalian-cell-derived alphaviruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K. M.; Heise M. Modulation of cellular tropism and innate antiviral response by viral glycans. J. Innate Immun. 2009, 1, 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabman R. S.; Rogers K. M.; Heise M. T. Ross River virus envelope glycans contribute to type I interferon production in myeloid dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 12374–12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim H. Y.; Koblet H. Asparagine-linked oligosaccharides of Semliki Forest virus grown in mosquito cells. Arch. Virol. 1992, 122, 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev S. V.; et al. Locations of carbohydrate sites on alphavirus glycoproteins show that E1 forms an icosahedral scaffold. Cell 2001, 105, 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecham J. O.; Trent D. W. Glycosylation patterns of the envelope glycoproteins of an equine-virulent Venezuelan encephalitis virus and its vaccine derivative. J. Gen. Virol. 1982, 63Pt 1121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.; et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Barmah Forest virus genome. Virology 1997, 227, 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgarno L.; et al. Characterization of Barmah forest virus: an alphavirus with some unusual properties. Virology 1984, 133, 416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne J. T.; Bell J. R.; Strauss E. G.; Strauss J. H. Pattern of glycosylation of Sindbis virus envelope proteins synthesized in hamster and chicken cells. Virology 1985, 142, 121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizki J. M.; Repik P. M. Structural protein relationships among eastern equine encephalitis viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75Pt 112897–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh P.; Robbins P. W. Regulation of asparagine-linked oligosaccharide processing. Oligosaccharide processing in Aedes albopictus mosquito cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 2375–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh P.; Rosner M. R.; Robbins P. W. Host-dependent variation of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides at individual glycosylation sites of Sindbis virus glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 2548–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth B. U.; Garoff H. The nucleocapsid-binding spike subunit E2 of Semliki Forest virus requires complex formation with the E1 subunit for activity. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 7857–7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S. C. Regulation of glycosylation. The influence of protein structure on N-linked oligosaccharide processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 19303–19317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N.; Sicheritz-Ponten T.; Gupta R.; Gammeltoft S.; Brunak S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd P. M.; Dwek R. A. Glycosylation: heterogeneity and the 3D structure of proteins. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997, 32, 1–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux P.; Varki A. Evolutionary considerations in relating oligosaccharide diversity to biological function. Glycobiology 1999, 9, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld R.; Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 631–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljestrom P.; Garoff H. Internally located cleavable signal sequences direct the formation of Semliki Forest virus membrane proteins from a polyprotein precursor. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karo-Astover L.; Sarova O.; Merits A.; Zusinaite E. The infection of mammalian and insect cells with SFV bearing nsP1 palmitoylation mutations. Virus Res. 2010, 153, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S. D.; Argos P. Is Sindbis a simple picornavirus with an envelope?. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 1099–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueninger-Leitch F.; D’Arcy A.; D’Arcy B.; Chene C. Deglycosylation of proteins for crystallization using recombinant fusion protein glycosidases. Protein Sci. 1996, 5, 2617–2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivol W. F.; Briegel A.; Jensen G. J. An improved cryogen for plunge freezing. Microsc. Microanal. 2008, 14, 375–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küster B.; Wheeler S. F.; Hunter A. P.; Dwek R. A.; Harvey D. J. Sequencing of N-linked oligosaccharides directly from protein gels: in-gel deglycosylation followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry and normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 250, 82–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börnsen K. O.; Mohr M. D.; Widmer H. M. Ion exchange and purification of carbohydrates on a Nafion(R) membrane as a new sample pretreatment for matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1995, 9, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Giles K.; et al. Applications of a travelling wave-based radio-frequency-only stacked ring ion guide. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 18, 2401–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. J. Fragmentation of negative ions from carbohydrates: Part 2, Fragmentation of high-mannose N-linked glycans. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2005, 16, 631–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. J.; Royle L.; Radcliffe C. M.; Rudd P. M.; Dwek R. A. Structural and quantitative analysis of N-linked glycans by MALDI and negative ion nanospray mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 376, 44–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. J.; et al. Ion mobility mass spectrometry for extracting spectra of N-glycans directly from incubation mixtures following glycan release: application to glycans from engineered glycoforms of intact, folded HIV gp120. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22, 568–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D.; Chen L.; O’Neill R. A. A detailed structural characterization of ribonuclease B oligosaccharides by 1H NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 261, 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E. D.; Adelt G.; Baenziger J. U.; Wilson S.; Van Halbeek H. The asparagine-linked oligosaccharides on bovine fetuin. Structural analysis of N-glycanase-released oligosaccharides by 500-megahertz 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 18253–18268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spik G.; et al. Studies on glycoconjugates. LXIV. Complete structure of two carbohydrate units of human serotransferrin. FEBS Lett. 1975, 50, 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M.; et al. A human embryonic kidney 293T cell line mutated at the Golgi alpha-mannosidase II locus. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 21684–21695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; et al. Engineering hydrophobic protein-carbohydrate interactions to fine-tune monoclonal antibodies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9723–9732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden T. A.; et al. Chemical and structural analysis of an antibody folding intermediate trapped during glycan biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17554–17563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B.; Costello C. E. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate J. 1988, 5, 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. J. Collision-induced fragmentation of underivatized N-linked carbohydrates ionized by electrospray. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000, 35, 1178–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D. W.; Peacock S.; Randles W. J. On the pathogenesis of Semliki forest virus (SFV) infection in the hamster. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1967, 48, 228–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble R. B.; Tarentino A. L. Identification of distinct endoglycosidase (endo) activities in Flavobacterium meningosepticum: endo F1, endo F2, and endo F3. Endo F1 and endo H hydrolyze only high mannose and hybrid glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 1646–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarentino A. L.; Gomez C. M.; Plummer T. H. Jr. Deglycosylation of asparagine-linked glycans by peptide:N-glycosidase F. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 4665–4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendic D.; Wilson I. B. H.; Paschinger K. The Glycosylation Capacity of Insect Cells. Croat. Chem. Acta 2008, 81, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; et al. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 6795–6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibriansah G.; et al. Structural changes in dengue virus when exposed to a temperature of 37 degrees C. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7585–7592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S. F.; Harvey D. J. Negative ion mass spectrometry of sialylated carbohydrates: Discrimination of N-acetylneuraminic acid linkages by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight and electrospray-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 5027–5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuochi T.; et al. Carbohydrate structures of the human-immunodeficiency-virus (HIV) recombinant envelope glycoprotein gp120 produced in Chinese-hamster ovary cells. Biochem. J. 1988, 254, 599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomelli C.; et al. The glycan shield of HIV is predominantly oligomannose independently of production system or viral clade. PLoS One 2011, 6, e23521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores K. J.; et al. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 13800–13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; et al. Determining the structure of an unliganded and fully glycosylated SIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Structure 2005, 13, 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwek R. A. Glycobiology: Toward Understanding the Function of Sugars. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 683–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M. D.; et al. Monoglucosylated glycans in the secreted human complement component C3: implications for protein biosynthesis and structure. FEBS Lett. 2004, 566, 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M.; Yu X.; Bowden T. A. Crystal structure of sialylated IgG Fc: Implications for the mechanism of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, E3544–3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden T. A.; et al. Unusual molecular architecture of the machupo virus attachment glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8259–8265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.; KewalRamani V. N. Dendritic-cell interactions with HIV: infection and viral dissemination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch D. H.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 2013, 503, 224–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejchal R.; et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science 2011, 334, 1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M.; Bowden T. A. Antibodies expose multiple weaknesses in the glycan shield of HIV. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 771–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. J.; et al. Proposal for a standard system for drawing structural diagrams of N- and O-linked carbohydrates and related compounds. Proteomics 2009, 9, 5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]