Abstract

Objective

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a progressive fibrosing disorder that may develop in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) after administration of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs). In the setting of impaired renal clearance of GBCAs, gadolinium (Gd) deposits in various tissues and fibrosis subsequently develops. However, the precise mechanism by which fibrosis occurs in NSF is incompletely understood. Because other profibrotic agents, such silica or asbestos, activate the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and initiate IL-1β release with the subsequent development of fibrosis, we evaluated the effects of GBCAs on inflammasome activation.

Methods

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) from C57BL/6, Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice were incubated with three Gd-containing compounds and IL-1β activation and secretion was detected by ELISA and Western blot analysis. Inflammasome activation and regulation was investigated in IL-4- and IFNγ-polarized macrophages by ELISA, qRT-PCR and NanoString nCounter analysis. Furthermore, C57BL/6 and Nlrp3−/− mice were injected i.p. with GBCA and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the peritoneum was analyzed by FACS.

Results

Both free Gd and GBCAs activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and induce IL-1β secretion in vitro. Gd-DTPA also induces the recruitment of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes to the peritoneum in vivo. Gd activated IL-4-polarized macrophages more effectively than IFNγ-polarized macrophages, which preferentially expressed genes known to downregulate inflammasome activity.

Conclusion

These data suggest that Gd released from GBCAs triggers a NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent inflammatory response that leads to fibrosis in an appropriate clinical setting. The preferential activation of IL-4-differentiated macrophages is consistent with the predominantly fibrotic presentation of NSF.

Keywords: gadolinium, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, inflammasome, NLRP3, macrophages

INTRODUCTION

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a progressive fibrosing disorder that primarily affects individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) following exposure to GBCAs administered for magnetic resonance imaging and angiography. NSF presents with skin thickening, tethering, and hyperpigmentation, accompanied by joint contractures that often result in limited mobility.[1, 2] Skin biopsies of established NSF lesions show thick and thin collagen bundles, few inflammatory cells, and a hypercellular dermis with prominent spindle cells derived from circulating fibrocytes.[3, 4] Multinucleated giant cells and dendritic cells that express CD68 and Factor XIIIa may also be present in the skin of patients with NSF.[5] Additionally, extracutaneous fibrosis may occur.[6, 7] A causal relationship between GBCA administration and the onset of NSF has been confirmed and Gd deposition has been identified in biopsies of affected tissues.[7–9] However, the precise mechanism by which fibrosis develops following GBCA exposure is incompletely understood.

Gd is a rare earth metal that is highly toxic in its free, unchelated form and is therefore complexed with an organic chelate when used as a contrast agent. It is believed that release of Gd from its chelate and its subsequent deposition in tissues plays an important role in the pathogenesis of NSF. The use of GBCAs with nonionic linear chelates, which release Gd more readily than those with macrocyclic chelates, [10] and the prolonged half-life of GBCAs in the circulation of patients with CKD, are important factors that contribute to the development of NSF.[11] The subcutaneous injection of mice with small amounts of GBCAs, which simulates GBCA extravasation, induced edema and inflammatory infiltrates containing neutrophils and macrophages in the dermis and subcutis.[12] Thus, as has been demonstrated in other fibrosing disorders such as diffuse systemic sclerosis, [13] the fibrotic stage of NSF might be preceded by an early inflammatory stage.

In vitro, GBCAs induce the production of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines by peripheral blood monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages[14, 15] and promote fibroblast activation and proliferation[16] and the production of extracellular matrix components, such as types I and III collagen and hyaluronic acid.[17] Signaling through toll-like receptors 4 and 7[18] and activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)[15] may mediate these biological effects. NLRP3 is a component of a family of protein complexes, called inflammasomes, which play an important role in innate immunity. Upon activation, NLRP3 interacts with the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain) to activate caspase-1 and mature and release interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18.[19] In addition to its proinflammatory effects, IL-1β can promote fibrosis without significant inflammation by stimulating fibroblasts directly[20, 21] and also by inducing TGF-β1, which then signals through the fibrogenic Smad3 pathway.[22] Because metal-containing particulate materials, such as alum and silica, induce fibrosis and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages, [23] we hypothesized that NLRP3 might also play a role in the development of Gd-induced fibrosis.

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is tightly regulated by a variety of mechanisms.[24] Recently, extracellular calcium, signaling through the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR), has been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome effectively.[25] High concentrations of free Gd also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome through the CASR, as Gd and calcium have similar ionic radii.[25] In the current report, we have extended these observations to demonstrate that GBCAs induce both the production of mature IL-1β by macrophages in vitro and peritoneal inflammation in vivo through NLRP3-dependent mechanisms.

Engagement of several signaling pathways during maturation drive macrophages to differentiate into subtypes that generally are classified into two groups: M1 and M2.[26–28] M1 and M2 macrophages differ in their immunologic roles as well as in their association with clinical conditions.[29, 30] M1 macrophages are considered to be proinflammatory and exhibit antimicrobial activity, whereas M2 macrophages are regarded as anti-inflammatory and are involved in wound healing and fibrogenesis.[26] A role for M2 macrophages has been proposed in the pathogenesis of SSc and other fibrosing disorders.[31] Thus, we also investigated the differential responses of M1 and M2 macrophages to stimulation with GBCAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice were provided by Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA, USA) and backcrossed to C57BL/6. The University of Massachusetts Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal experiments.

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM)

Bone marrow cells were harvested from long bones of C57BL/6 (WT), Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice. Macrophage development was promoted by culturing the cells for 7 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin, streptomycin and 20% L929-conditioned medium. Cells were then harvested and replated in 12-well-plates at a concentration of 5×105 cells per well. In separate experiments, differentiation into M1 and M2 macrophages was also induced on the next day by incubation for 4 hours with 150 U/ml IFNγ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or 20 U/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems), respectively. All cells were primed for 4 hours with serum free DMEM containing 20 ng/ml ultra-pure lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA), at which time Gd-containing compounds were added for an additional 6 hours. Nigericin, poly(dA:dT), and silica were prepared and used as described.[23, 32] Cell culture supernatants and cell lysates were collected for ELISA and immunoblotting. Cell viability was evaluated in each experiment by microscopic examination of cells for viability and, in several experiments, by flow cytometry using the DNA intercalating agent TO-PRO-3 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) to stain for dead cells.

Chemicals

Omniscan®, consisting of gadolinium complexed with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic-acid-bis-methylamide (DTPA-BMA), was provided by GE Healthcare (Waukesha, WI, USA). Nigericin and poly(dA:dT) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Silica crystals were obtained from US Silica (Frederick, MD, USA). Gd-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA), and Gd chloride (GdCl3) were also obtained from Sigma and diluted in sterile water to 500 mM, pH 7.4. Lipofectamine 2000 was obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). For in vitro and in vivo studies, reagents were diluted in DMEM or phosphate buffered saline (PBS), respectively.

ELISA and Western Blotting

IL-1β present in the culture fluids was quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems). IL-1β processing was determined by Western blot, as described, [33] using goat anti-mouse IL-1β (R&D Systems) and anti-β-actin antibody for loading control (Sigma).

Gene expression analysis

Differentiation into M1 and M2 macrophages was verified by qRT-PCR for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos) and arginase 1 (arg1), respectively. RNA was isolated with Qiagen RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and Quanta qScript (Quanta Bioscience, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used for reverse transcription. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with specific primer pairs (Supplementary Figure). Gene expression is presented relative to the housekeeping-gene guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 (GNB2L1). RNA samples, isolated from unpolarized or M1- or M2-polarized macrophages that had then been primed with LPS, were analyzed with the NanoString nCounter Analysis System (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA). Unprimed BMDM served as control. Samples were prepared and data analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene expression is reported relative to the housekeeping-genes glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β-glucuronidase (GUSB), hypoxanthinphosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1), and clathrin heavy chain 1 (CLTC).

Cell recruitment to peritoneal cavity

Nine to ten week old male C57BL/6 and Nlrp3−/− mice were injected i.p. with 500 μM Gd-DTPA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). PBS injected C57BL/6 served as controls. After 24 hours, mice were euthanized and cells were collected from the peritoneal cavity. Cells were stained for flow cytometry with anti-CD11b, anti-Ly6G (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and anti-Ly6C (AbDSerotec, Raleigh, NC, USA), recorded on a LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism, Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and are shown as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using an unpaired Student t test or ANOVA, as indicated. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Gd-containing compounds induce IL-1β secretion

Chronic inflammation can trigger a fibrotic tissue response by several mechanisms.[20–22, 34] Since exposure to Gd-containing compounds has been associated with the subsequent development of systemic fibrosis, we assessed whether Gd-containing compounds could induce the release of the cytokine IL-1β. BMDM from C57BL/6 mice were primed with LPS to promote NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression and were then treated with increasing concentrations of three different Gd-containing compounds: GdCl3, Omniscan® and Gd-DTPA. GdCl3 is a salt of Gd, which is not complexed to any chelate. Omniscan® is an aqueous solution of a GBCA that is used for intravenous injection and which contains 287 mg/mL (0.5 mol/L) of gadodiamide and 12 mg/mL of excess chelate (caldiamide). Gd-DTPA is the GBCA in Magnevist®, but without the excess chelate (meglumine and diethylenetriaminepentaaceticacid) that is present in the aqueous solution used for intravenous injection. These agents were selected to determine whether the observed outcomes were due to free Gd and whether chelating agents might have a protective impact on Gd-mediated effects. The NLRP3 inflammasome activator nigericin and the AIM2 inflammasome ligand poly(dA:dT) were used as controls.

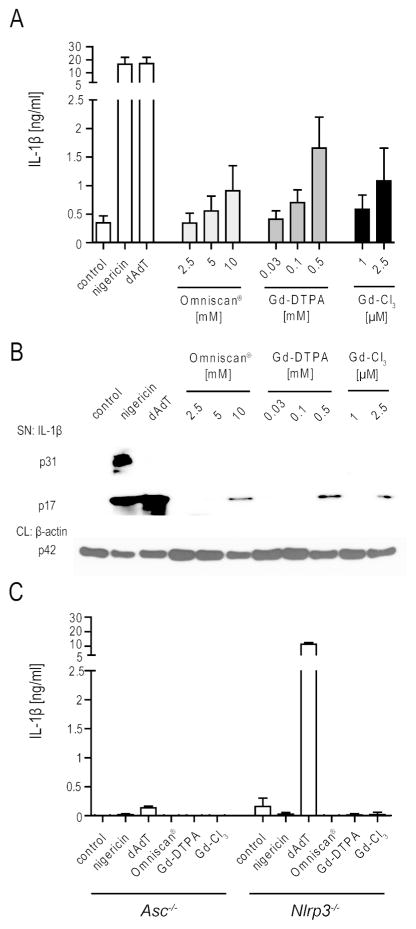

All three tested Gd-containing compounds induced the concentration-dependent secretion of processed IL-1β, as detected in culture fluids by ELISA (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the free Gd salt GdCl3 was the most potent activator, inducing the release of detectable IL-1β levels (1085 ± 576 pg/ml) at a concentration of 2.5 μM. A 200-fold higher concentration of Gd-DTPA (500 μM) and a 4000-fold higher concentration of the GBCA Omniscan® (10 mM) also induced IL-1β production (Fig. 1A). For all three substances, Western blot analysis confirmed that pro-IL-1β was processed to mature IL-1β (Fig. 1B). None of the Gd-containing compounds induced evidence of increased cell death; in contrast, nigericin induced extensive cell death with release of pro-IL-1β into the culture supernatants (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that Gd containing compounds activate IL-1β release from BMDMs and suggest that the free unchelated Gd salt is the active agent that induces processing of IL-1β.

Figure 1.

Induction of processed IL-1β by GBCA is dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome. (A) IL-1β secretion by BMDM obtained from WT mice after LPS priming (20 ng/ml) and stimulation with the indicated concentrations of Gd containing compounds, compared to stimulation by nigericin (1hr) and poly(dA:dT) (6 hrs), as detected by ELISA. (B) Western blot analysis of supernatants (SN) and cell lysates (CL) from BMDM described above, analyzed for IL-1β and for β-actin, respectively. (C) IL-1β secretion of BMDM obtained from Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice. Omniscan®, Gd-DTPA and Gd-Cl3 were used at 10mM, 500 μM and 2.5 μM, respectively. Values are mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments, each with duplicates of BMDM obtained from one mouse.

Gd-induced IL-1β release depends on NLRP3

Both inflammasome- and non-inflammasome-mediated pathways can induce IL-1β cleavage.[19, 35, 36] Maturation of IL-1β by inflammasomes usually depends on the caspase-1-binding adaptor protein ASC.[19] To determine whether Gd compounds mature IL-1β through an inflammasome-dependent mechanism, the Gd-containing reagents were assayed using BMDM from Asc−/− mice. None of the Gd-containing reagents induced IL-1β release from the Asc−/− BMDM, thereby implicating the activation of an ASC-dependent inflammasome in the Gd-induced release of IL-1β (Fig. 1C).

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in the inflammatory response to a range of chemical and crystal compounds. To determine whether Gd activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, BMDM from NLRP3-deficient mice were included in our analysis. Nlrp3−/−- BMDM were as unresponsive to the Gd-containing compounds as Asc−/− BMDM (Fig. 1C). As expected, nigericin, which activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by binding to NLRP3, did not activate either Asc−/− or Nlrp3−/− BMDM. The AIM2 ligand poly(dA:dT) induced IL-1β release from Nlrp3−/−, but not from Asc−/− cells. These data show that free Gd and GBCA induce the secretion of IL-1β through engagement of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

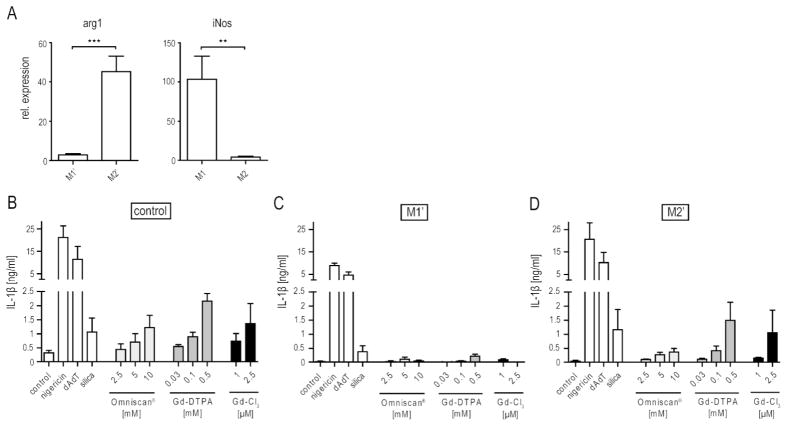

GBCA preferentially activate M2′ macrophages

M1 macrophages are generally considered to be proinflammatory, whereas M2 macrophages are largely associated with healing and fibrosis.[37] Polarizing BMDM with IFNγ or IL-4 generated M1 and M2 macrophages, respectively (Fig. 2A). Both types of macrophages were then primed with low doses of LPS to induce pro-IL-1β expression. Because the M2 subset is often analyzed without prior LPS-priming, we will refer to these primed macrophages as M2′. Similarly, we will refer to LPS-primed M1 cells as M1′. Polarization of both the M1′ and M2′ subsets was confirmed for each experiment by qPCR of the M1-associated gene iNos and the M2-associated gene arginase 1.[38] As expected, iNos and arginase 1 expression were highly up-regulated in M1′ and M2′ macrophages, respectively (Fig. 2A), and thus were similar to non-LPS-primed M1 and M2 macrophages.

Figure 2.

Effect of macrophage polarization on GBCA-induced IL-1β production. (A) Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos) and arginase 1 (arg1) in IFNγ- and IL-4-polarized macrophages after LPS priming (20 ng/ml for 4 hrs) expressed relative to the housekeeping gene guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 (GNB2L1), as measured by qRT-PCR. Values are mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments. (B–C) IL-1β secretion of IFNγ-polarized (B) and IL-4-polarized (C) cells after LPS priming (20 ng/ml) and incubation with Gd containing compounds, poly(dA:dT) or silica (200 μg/ml) for 6 hrs or nigericin for 1 hr. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each with duplicates of BMDM obtained from one mouse. Statistical significance: ★= p<0.05; ★★= p<0.01; ★★★=p<0.001.

The polarized populations were then incubated with nigericin, poly(dA:dT), or silica, as well as with the three Gd-containing compounds. Strikingly, undifferentiated and M2′ macrophages secreted more IL-1β in response to each of the Gd-containing compounds than did M1′ macrophages, in which the response was barely detectable (Fig. 2B). Even the M2′ responses to nigericin and silica were approximately twice those of the M1′ responses. This effect was not NLRP3-specific, since poly(dA:dT) also induced a decreased response in M1′ macrophages (Fig. 2B).

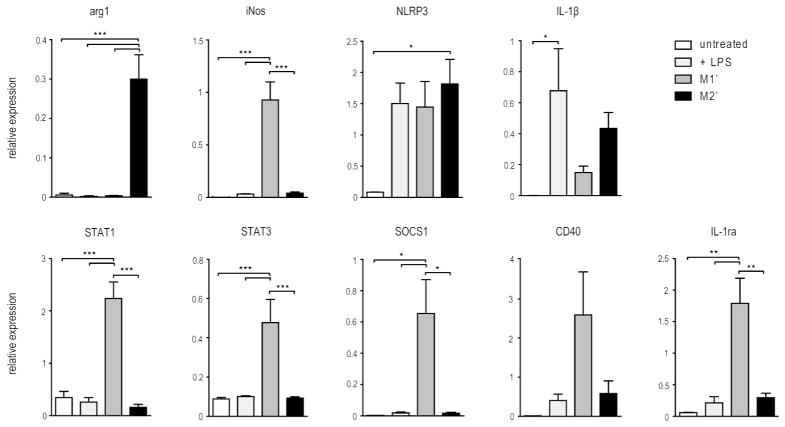

Whereas type 1 and type 2 interferons have been shown to regulate inflammasome activation, [39, 40] inflammasome regulation has not been rigorously compared in LPS-primed M1 and M2 subsets. To further explore the potential pro-inflammatory activity of M1′ and M2′ macrophages, the expression of known inflammasome regulators was evaluated using a non-enzymatic RNA profiling technology employing bar-coded fluorescent probes to analyze mRNA expression levels of a selection of genes simultaneously (nCounter, Nanostring). This analysis revealed a number of important similarities and intriguing differences (Fig. 3). LPS priming induced comparable NLRP3 expression in M1′ and M2′ cells. However, about 3-times as much IL-1β was expressed by the M2′ cells, consistent with recently published data showing down-regulation of IL-1β by IFNγ. [41] Importantly, we found that STAT1 and STAT3, both known to negatively regulate inflammasome signaling, were expressed at much higher levels in the M1′ cells. Furthermore, CD40 and SOCS1 have been proposed to inhibit inflammasome signaling and both were up-regulated in M1′, but not M2′, macrophages.[24, 41] The M1′ macrophages were functional, since they exhibited increased CD40 and SOCS1 expression. The IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1ra was also up-regulated in M1′ cells. These gene expression patterns are consistent with the higher IL-1β levels secreted by the M2′ than by the M1′ subset.

Figure 3.

Gene expression profiles of IFNγ- and IL-4-polarized BMDM. mRNA expression of inflammasome regulating genes detected with the NanoString nCounter in untreated and LPS primed (20 ng/ml) macrophages as well as IFNγ- and IL-4-polarized BMDM obtained as described in the methods. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each using BMDM obtained from different mice. Statistical significance: ★= p<0.05; ★★= p<0.01; ★★★=p<0.001.

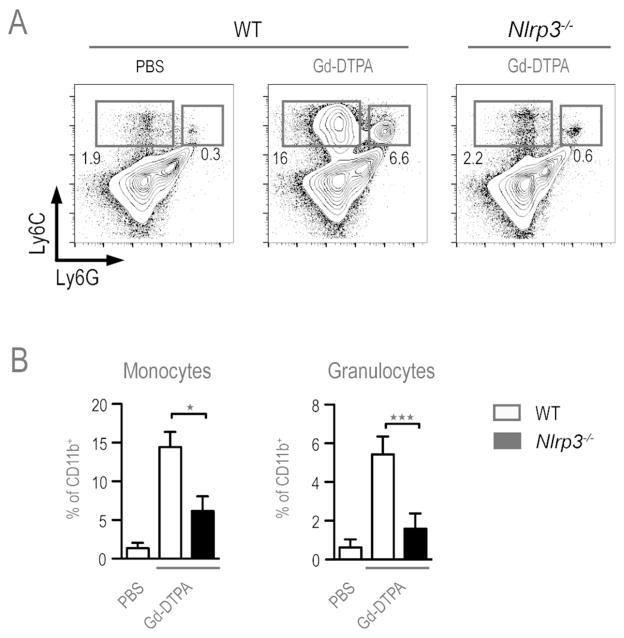

The in vivo inflammatory response to Gd is NLRP3-dependent

To determine whether chelated Gd compounds trigger inflammasome activation in vivo, WT and Nlrp3−/− mice were injected i.p. with Gd-DTPA or PBS and the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes into the peritoneal cavity was measured after 24 hours. Mice receiving Gd-DTPA showed both a relative and an absolute increase in the number of inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+, Ly6Chi, Ly6Gint) and granulocytes (CD11b+, Ly6Cint, Ly6Ghi), compared to PBS injected mice (Fig. 4). This inflammatory response was dependent upon the NLRP3 inflammasome, since the influx of inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes was markedly reduced in Nlrp3−/− mice compared to Gd-DTPA injected WT mice (Fig. 4). These results demonstrate that recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and granulocytes into the peritoneal cavity, in response to GBCA, requires engagement of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 4.

Gd-DTPA induced peritoneal inflammation. WT and Nlrp3−/− mice were injected with either PBS or 500 μM Gd-DPTA in PBS and peritoneal exudate cells were collected 24 hrs later. CD11b+ cells were further stained for Ly6C and Ly6G expression to identify inflammatory monocytes (Ly6C+ Ly6Gint) and granulocytes (Ly6C+ Ly6G+). (A) Representative FACS plots. (B) Bar graphs displaying mean ± SEM for compiled data from 3 experiments involving WT (n=8) and Nlrp3−/−(n=7) mice. Statistical significance: ★= p<0.05; ★★= p<0.01; ★★★=p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

GBCA exposure is essential for the development of NSF.[42] However, the mechanism by which tissue fibrosis develops is incompletely understood. At the time of diagnosis, examination of NSF patient skin biopsies typically reveals extensive fibrosis with little evidence of inflammation.[3] However, the possibility of an initial inflammatory phase is supported by the observation that subcutaneous injection of mice with GBCA produce an inflammatory response.[12] Furthermore, biopsies of NSF patients obtained within 20 weeks of disease onset show some evidence of inflammation.[43, 44] The occasional presence of CD68- and Factor XIIIa-positive inflammatory cells in skin biopsies from patients with NSF supports the concept that inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of NSF.[5] However, most biopsies are not performed early enough to detect such an inflammatory response prior to the onset of cutaneous fibrosis. Our data, which demonstrate the rapid NLRP3-dependent IL-1β induction by Gd-containing compounds, support the hypothesis that NSF begins as an inflammatory response to GBCA.

IL-1β can also directly induce transformation of human epithelioid dermal microvascular endothelial cells into myofibroblasts.[45] In systemic sclerosis (SSc), a disease with cutaneous features similar to those of NSF, inflammasome involvement in fibrogenesis is suggested by the upregulation of 40 genes involved in inflammasome signaling in dermal fibroblasts obtained from SSc patients, as compared to those from healthy individuals.[46] In addition, caspase-1 inhibition decreases the expression and secretion of collagen by SSc dermal and lung fibroblasts.[46] Deposition of urate crystals, which activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, [47] has been demonstrated in biopsies of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis and has been hypothesized to initiate the development of fibrosis in some patients with this disease.[48]

Persistent induction of cytokines downstream of NLRP3 and IL-1β induced by local Gd deposits in affected tissues could then promote the development of fibrosis, as has been shown for disorders such as silicosis.[49] Moreover, a macrophage infiltrate is present in skin biopsies of SSc patients.[50] An initial inflammatory phase with accumulation of mononuclear cells and increased TGF-β and chemokine expression, followed by dermal fibrosis, is also seen in mice injected subcutaneously with bleomycin.[13] Consistent with the inflammatory response consisting of neutrophils and macrophages after subcutaneous GBCA injection of mice with GBCA, [12] we demonstrate recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the peritoneal cavity following intraperitoneal GBCA injection. This process is NLRP3-dependent, either as a direct effect of IL-1β and/or danger signals released from inflammasome-induced pyroptosis.

Progression from inflammation to fibrosis is consistent with data from a poly-IC driven model of dermal fibrosis.[34] However, the exact mechanism(s) linking inflammation to fibrosis remain unclear. Importantly, IL-1β has remarkable effects on fibrosis and fibroblast migration and thus might be an important molecule linking inflammation to the fibrosis induced by Gd.[22, 51]

GBCAs could activate NLRP3 through engagement of CASR, as recently described for free Gd, using GdCl3 concentrations that were 1000-fold higher than in our experiments.[25] We further show that unchelated Gd triggers the inflammatory response most efficiently. Free Gd that has dissociated from the chelate most likely accounts for the observed effects of the GBCAs, since much higher doses of the chelated forms of Gd were needed to induce IL-1β production. The pro-inflammatory effects of a GBCA cannot be predicted based upon the chemical structure of the chelate, since the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by monocytes can be induced by GBCAs with either linear or macrocyclic chelates.[52] However, a protective effect of chelating agents is supported by the fact that Omniscan®, which contains excess chelating agent, was less stimulating than Gd-DTPA, which does not. Nevertheless, the effective Omniscan® concentration in our system was still relevant to doses used clinically: plasma levels of approximately 5 mM have been reported following the intravenous injection of 0.1 mmol/kg gadodiamide in patients with CKD, [11] and tissue levels are likely to be much higher.

We also show that different macrophage subtypes have diverging responses to inflammasome activators. Classically, macrophages are categorized as inflammatory M1 macrophages and as M2 macrophages associated with fibrosis and wound healing.[26] However, this classification seems to be a simplification of the diversity of matured macrophages.[27, 28] Most studies on M2 function have failed to take into account the importance of a priming signal, normally delivered by a TLR ligand, in inflammasome activation. Priming macrophages with LPS for longer than was done in this study can also shift macrophage polarization.[53] In our study, primed M1′ and M2′ macrophages still expressed typical M1 and M2 markers. Although ATP and other inflammasome activators have been reported to activate predominantly M1 macrophages, [27] we found that priming of M2 macrophages with low dose LPS resulted in stronger responses to Gd, nigericin, silica, and poly(dA:dT) than those seen in LPS-primed M1 macrophages. Thus, this difference is not specific for the NLRP3 inflammasome or for certain inflammasome stimulants, such as particulates. Reasons for this dichotomy are likely to include differential regulation of inflammasome-regulating genes. Consistent with the study by Masters et al., [41] we present evidence that IFNγ pretreatment reduces IL-1β secretion, presumably as a result of decreased IL-1β mRNA expression and increased STAT3 expression, further reducing IL-1β synthesis.[39] Overexpression of SOCS1 and CD40 in M1′ macrophages could play a role in maintaining this suppression. The up-regulation of STAT1 in M1′ macrophages, may also contribute to the decreased IL-1β production, as STAT1 has been reported to suppress caspase-1 maturation.[24]

Although up-regulation of IL-1ra seen in M1′ cells in these experiments probably would not account for the effects observed in this study, IL-1ra might limit the pro-fibrotic effects of M1 cells in vivo, since it has been shown to have anti-fibrotic effects in the lung in vivo.[54] Together, the gene expression profile of M2′ compared to M1′ cells is consistent with a more protracted inflammasome-driven response in M2′ cells following Gd exposure. It will be important to determine whether the differential expression of such genes represents a universal distinction between M1′ and M2′ macrophages in vivo.

The preferential activation of M2′ macrophages by Gd is consistent with the predominantly fibrotic presentation of NSF.[3] M2 macrophages have been detected in the skin of SSc patients who show a similar cutaneous presentation to NSF.[55] A possible explanation for the predilection of certain patients to develop NSF is that their macrophages might be programmed genetically to an M2-like phenotype; in IgA nephropathy, fibrosis has been linked to the presence of M2-like macrophages in the kidney.[56] Our finding that Gd induced a rapid NLRP3-dependent response in vivo, might pave the way for new therapeutic strategies. For example, patients developing inflammation at the site of GBCA injection could be treated with an IL-1 antagonist or an inhibitor of inflammasome activation, such as a caspase-1 inhibitor, which might prevent progression to chronic inflammation and fibrosis. In fact, NLRP3-deficient mice have been shown to be resistant to bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis.[46]

In summary, this study shows that Gd and GBCA activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, primarily in undifferentiated and LPS-primed M2 macrophages. The NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in the rapid recruitment of inflammatory monoctyes and granulocytes to the site of Gd deposition in vivo. However, further studies are needed to clarify the relative roles of NLRP3 inflammasome activation with IL-1β secretion and M2 macrophage polarization in the pathogenesis of NSF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ping-I Chiang and Hsun Fan Wang for technical assistance and Peter Düwell, Tia Bumpus and Vijay A.K. Rathinam for advice and discussion.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Alliance for Lupus Research (to A.M.R) and NIH grant HL093262 (to E.L.). C.S.-L. was supported by the Biomedical Sciences Exchange Program (Hannover, Germany).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

Licence for Publication

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in ARD and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms).

References

- 1.Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, et al. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356:1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02694-5. published Online First: 2000/10/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moschella SL, Kay J, Mackool BT, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 35-2004. A 68-year-old man with end-stage renal disease and thickening of the skin. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc049026. published Online First: 2004/11/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girardi M, Kay J, Elston DM, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1095–1106 e1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.041. published Online First: 2011/07/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383–393. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00001. published Online First: 2002/01/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez SA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, et al. Dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy): study of inflammatory cells and transforming growth factor beta1 expression in affected skin. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2660–2666. doi: 10.1002/art.20362. published Online First: 2004/08/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koreishi AF, Nazarian RM, Saenz AJ, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a pathologic study of autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1943–1948. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.12.1943. published Online First: 2009/12/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay J, Bazari H, Avery LL, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 6-2008. A 46-year-old woman with renal failure and stiffness of the joints and skin. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:827–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc0708697. published Online First: 2008/02/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd AS, Zic JA, Abraham JL. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.High WA, Ayers RA, Chandler J, et al. Gadolinium is detectable within the tissue of patients with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.047. published Online First: 2006/11/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenzel T, Lengsfeld P, Schirmer H, et al. Stability of gadolinium-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents in human serum at 37 degrees C. Invest Radiol. 2008;43:817–828. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181852171. published Online First: 2008/11/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joffe P, Thomsen HS, Meusel M. Pharmacokinetics of gadodiamide injection in patients with severe renal insufficiency and patients undergoing hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Acad Radiol. 1998;5:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80191-8. published Online First: 1998/07/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Runge VM, Dickey KM, Williams NM, et al. Local tissue toxicity in response to extravascular extravasation of magnetic resonance contrast media. Invest Radiol. 2002;37:393–398. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200207000-00006. published Online First: 2002/06/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–567. doi: 10.1172/jci31139. published Online First: 2007/03/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wermuth PJ, Del Galdo F, Jimenez SA. Induction of the expression of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes by gadolinium contrast agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1508–1518. doi: 10.1002/art.24471. published Online First: 2009/05/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Galdo F, Wermuth PJ, Addya S, et al. NFkappaB activation and stimulation of chemokine production in normal human macrophages by the gadolinium-based magnetic resonance contrast agent Omniscan: possible role in the pathogenesis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2024–2033. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134858. published Online First: 2010/10/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edward M, Quinn JA, Burden AD, et al. Effect of different classes of gadolinium-based contrast agents on control and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis-derived fibroblast proliferation. Radiology. 2010;256:735–743. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091131. published Online First: 2010/07/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piera-Velazquez S, Louneva N, Fertala J, et al. Persistent activation of dermal fibroblasts from patients with gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2017–2023. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127761. published Online First: 2010/06/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wermuth PJ, Jimenez SA. Gadolinium Compounds Signaling through TLR 4 and TLR 7 in Normal Human Macrophages: Establishment of a Proinflammatory Phenotype and Implications for the Pathogenesis of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. J Immunol. 2012;189:318–327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103099. published Online First: 2012/06/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stutz A, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Inflammasomes: too big to miss. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3502–3511. doi: 10.1172/jci40599. published Online First: 2009/12/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postlethwaite AE, Raghow R, Stricklin GP, et al. Modulation of fibroblast functions by interleukin 1: increased steady-state accumulation of type I procollagen messenger RNAs and stimulation of other functions but not chemotaxis by human recombinant interleukin 1 alpha and beta. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:311–318. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.311. published Online First: 1988/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postlethwaite AE, Smith GN, Jr, Lachman LB, et al. Stimulation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis in cultured human dermal fibroblasts by interleukin 1. Induction of hyaluronic acid synthesis by natural and recombinant interleukin 1s and synthetic interleukin 1 beta peptide 163–171. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:629–636. doi: 10.1172/jci113927. published Online First: 1989/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonniaud P, Margetts PJ, Ask K, et al. TGF-beta and Smad3 signaling link inflammation to chronic fibrogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175:5390–5395. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5390. published Online First: 2005/10/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. published Online First: 2008/07/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rathinam VA, Vanaja SK, Fitzgerald KA. Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:333–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2237. published Online First: 2012/03/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature. 2012;492:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11588. published Online First: 2012/11/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. published Online First: 2003/01/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Dynamics of macrophage polarization reveal new mechanism to inhibit IL-1beta release through pyrophosphates. EMBO J. 2009;28:2114–2127. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.163. published Online First: 2009/06/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005;23:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. published Online First: 2005/10/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. published Online First: 2010/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. published Online First: 2006/03/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lappalainen U, Whitsett JA, Wert SE, et al. Interleukin-1beta causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:311–318. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0309OC. published Online First: 2005/01/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. published Online First: 2010/04/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. published Online First: 2010/12/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farina GA, York MR, Di Marzio M, et al. Poly(I:C) drives type I IFN- and TGFbeta-mediated inflammation and dermal fibrosis simulating altered gene expression in systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2583–2593. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.200. published Online First: 2010/07/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guma M, Ronacher L, Liu-Bryan R, et al. Caspase 1-independent activation of interleukin-1beta in neutrophil-predominant inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3642–3650. doi: 10.1002/art.24959. published Online First: 2009/12/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossaller L, Chiang PI, Schmidt-Lauber C, et al. Cutting Edge: FAS (CD95) Mediates Noncanonical IL-1beta and IL-18 Maturation via Caspase-8 in an RIP3-Independent Manner. J Immunol. 2012;189:5508–5512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202121. published Online First: 2012/11/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. published Online First: 2011/10/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. published Online First: 2008/12/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, et al. Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2011;34:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.006. published Online First: 2011/02/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra BB, Rathinam VA, Martens GW, et al. Nitric oxide controls the immunopathology of tuberculosis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent processing of IL-1beta. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:52–60. doi: 10.1038/ni.2474. published Online First: 2012/11/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masters SL, Mielke LA, Cornish AL, et al. Regulation of interleukin-1beta by interferon-gamma is species specific, limited by suppressor of cytokine signalling 1 and influences interleukin-17 production. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:640–646. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.93. published Online First: 2010/07/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kay J, Czirjak L. Gadolinium and systemic fibrosis: guilt by association. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1895–1897. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134791. published Online First: 2010/10/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steger-Hartmann T, Raschke M, Riefke B, et al. The involvement of pro-inflammatory cytokines in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis - a mechanistic hypothesis based on preclinical results from a rat model treated with gadodiamide. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61:537–552. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.11.004. published Online First: 2009/01/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan AW, Tan SH, Lian TY, et al. A case of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:527–529. published Online First: 2004/08/27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhuri V, Zhou L, Karasek M. Inflammatory cytokines induce the transformation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells into myofibroblasts: a potential role in skin fibrogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:146–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00584.x. published Online First: 2006/09/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Artlett CM, Sassi-Gaha S, Rieger JL, et al. The inflammasome activating caspase 1 mediates fibrosis and myofibroblast differentiation in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3563–3574. doi: 10.1002/art.30568. published Online First: 2011/07/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, et al. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. published Online First: 2006/01/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cullen TH. Retroperitoneal fibroses--an association with hyperuricaemia. Br J Surg. 1981;68:199–200. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rimal B, Greenberg AK, Rom WN. Basic pathogenetic mechanisms in silicosis: current understanding. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:169–173. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000152998.11335.24. published Online First: 2005/02/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishikawa O, Ishikawa H. Macrophage infiltration in the skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1202–1206. published Online First: 1992/08/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saalbach A, Klein C, Schirmer C, et al. Dermal fibroblasts promote the migration of dendritic cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:444–454. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.253. published Online First: 2009/08/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wermuth PJ, Jimenez SA. Induction of a type I interferon signature in normal human monocytes by gadolinium-based contrast agents: comparison of linear and macrocyclic agents. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:113–125. doi: 10.1111/cei.12211. published Online First: 2013/12/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng XF, Hong YX, Feng GJ, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced M2 to M1 macrophage transformation for IL-12p70 production is blocked by Candida albicans mediated up-regulation of EBI3 expression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. published Online First: 2007/06/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higashi-Kuwata N, Makino T, Inoue Y, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages) in the skin of patient with localized scleroderma. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:727–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00828.x. published Online First: 2009/03/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikezumi Y, Suzuki T, Karasawa T, et al. Identification of alternatively activated macrophages in new-onset paediatric and adult immunoglobulin A nephropathy: potential role in mesangial matrix expansion. Histopathology. 2011;58:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03742.x. published Online First: 2011/02/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.