Abstract

Objective

Life stress consistently increases the incidence of major depression. Recent evidence has shown that individual symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) differ in important dimensions such as their genetic and etiological background, but the impact of stress on individual MDD symptoms is not known. Here we assess whether stress affects depression symptoms differentially.

Method

We used the chronic stress of medical internship to examine changes of the nine DSM-5 criterion symptoms for depression in 3,021 interns assessed prior to and throughout internship.

Results

All nine depression symptoms increased in response to stress (all p < 0.001), on average by 173%. Symptom increases differed substantially from each other (p < 0.001), with psychomotor problems (289%) and interest loss (217%) showing the largest increases, and suicidal ideation (146%) and sleep problems (52%) the smallest. Symptoms also differed in their severities under stress (p < 0.001): fatigue, appetite problems and sleep problems were most prevalent, psychomotor problems and suicidal ideation were least prevalent.

Conclusion

Stress differentially affects the DSM-5 depressive symptoms. Analyses of individual symptoms reveal important insights obfuscated by sum-scores.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder, life stress, internship

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a highly heterogeneous disorder (1–3). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) (4) uses nine symptoms to define depression, three of which are comprised of opposite symptoms (e.g., ‘insomnia or hypersomnia’), leading to 1,497 unique symptom profiles that qualify for the same diagnosis (5). In line the with the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) strategic plan for mood disorder research (6), a growing body of evidence suggests that the analysis of individual depression symptoms is an untapped source of important and clinically relevant data. For instance, MDD symptoms differ from each other in their genetic (7–9) and etiological (10) background, differentially impact impairment of psychosocial functioning (11), and show differential associations with important clinical variables such as demographic information, personality traits, life events, and lifetime comorbidities (12).

Life stress is one of the most robust triggers for MDD (13,14). Elevated levels of depression after experiencing stress have been documented both in patients and general population samples (14,15), with depression rates 2.5 to 7 times higher for individuals exposed to serious stressors (16,17). Despite the overwhelming evidence that depression diagnoses are increased in the context of stress, we know little about the behavior of individual depressive symptoms in response to stress.

Here we prospectively investigate the impact of life stress on the nine DSM MDD criterion symptoms in a cohort study of interns. Internship is a well-established serious chronic stressor, and interns are faced with long work hours, sleep deprivation, loss of autonomy, as well as extreme emotional situations (18,19). In a previous longitudinal study of interns, depression levels increased from 3.9% at baseline to 25.7% during internship (20). Utilizing internship as prospective stress model offers the opportunity to assess depression symptoms in a large sample before and after the reliable onset of severe chronic stress.

Aims of the study

The present report uses a cohort of 3,021 interns to examine whether internship stress impacts some depression symptoms more strongly than others, as well as the magnitude of potential differences.

Material and methods

Sample

7,429 interns entering internship programs in the USA during the 2007-2012 academic years were invited to participate in the study; 59 percent (N = 4,383) accepted the invitation. The institutional review boards at participating hospitals approved the study. Participating subjects provided electronic informed consent, and were given $50 in gift certificates.

Assessment

All surveys were conducted through a secure online website designed to maintain confidentiality. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (21). The PHQ-9 is a self-report component of the PRIME-MD inventory that screens for the DSM-5 criterion symptoms of depression. For each of the nine symptoms, subjects indicated whether, during the previous 2 weeks, the symptom had bothered them “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day.” Each item yields a score of 0, 1, 2 or 3. The nine symptoms assessed by the PHQ-9 are: ‘little interest or pleasure in doing things’ (interest), ‘feeling depressed or hopeless’ (mood), ‘sleep problems’ (sleep), ‘feeling tired’ (fatigue), ‘appetite problems’ (appetite), ‘feeling bad about yourself / that you are a failure’ (self-blame), ‘trouble concentrating on things’ (concentration), ‘moving or speaking slowly / being fidgety or restless’ (psychomotor), and ‘suicidal ideation’ (suicide).

Subjects completed a baseline survey 1-2 months prior to commencing internship that assessed general demographic factors (age, sex) and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9). Participants were contacted via email 3,6,9 and 12 months into their internship year and asked to complete the PHQ-9 again.

Statistical Analysis

We compared symptom severity at baseline with average symptom severity during the four measurements across the internship. This approach has been used in previous publications based on this dataset (10,20), and has the advantage of increased reliability of symptom assessment within internship through repeated measurement. When averaging the within-internship symptom scores, 1,362 (31.1%) of the 4,383 subjects were dropped via listwise deletion because they had missing data on two or more time points, leaving 3,021 interns in the analytic sample.

Overall, three analyses were performed. First, we investigated whether PHQ-9 symptoms increased with stress. We used one paired samples t-test per symptom to compare severities, and adjusted p-values for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Second, we tested whether symptoms differed from each other in response to stress, a test to assess whether stress had differential impacts on specific depressive symptoms. Instead of performing 36 individual tests comparing each symptom increase against all other symptom increases, we conducted one omnibus test. We fitted two longitudinal mixed models to the data with the subject variable as a random effect, using the LMER function of the R-package LME4 (22). In model I, symptom increases from baseline to the stress condition were allowed to be freely estimated, whereas increases were constrained to be equal in model II (i.e. slopes were forced to be equal). We then examined whether the constrained model II showed significantly decreased model fit compared to model I, as would be expected if symptoms increased differentially in response to stress. We compared models using a χ2-difference test, and used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (23) as goodness-of-fit statistic (the lower the value, the better the fit).

Third, we examined the stress condition symptom score to see if the nine depressive symptoms differed in their severities after stress onset. Similar to analyses two we performed one omnibus test by fitting two mixed models to the cross-sectional data of timepoint two using the LMER function of the R-package LME4, once again using the subject variable as random effect. Model I allowed for a free estimation of symptom severities, while model II constrained all symptoms to have equal severities. Model fit was compared similar to analysis two.

Lastly, we provide detailed descriptive information about symptom severity and increases. Analysis one was performed using SPSS v21.0 (24), analyses two and three with R v3.1.0 (25). We consider p-values of <0.05 significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

3,021 individuals were included in the analyses; 48.4% of the study participants were male, and the mean age was 27.5 (SD = 2.7) (Table 1). Participants that were dropped due to missing values did not differ significantly from the retained participants regarding the variables age, sex, or history of depression (all p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 1462 (48.4) |

| Female | 1559 (52.6) |

| Age, y | |

| ≤25 | 536 (17.7) |

| 26-30 | 2146 (71) |

| 31-35 | 281 (9.3) |

| >35 | 58 (1.) |

| History of depression | |

| Yes | 1326 (43.9) |

| No | 1693 (55.1) |

| Specialty | |

| Internal Medicine | 1106 (36.6) |

| Other | 394 (13) |

| Pediatrics | 350 (11.6) |

| General Surgery | 306 (10.1) |

| Psychiatry | 217 (7.2) |

| Emergency Medicine | 197 (6.5) |

| Family Medicine | 137 (4.5) |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 123 (4.1) |

| Internal medicine/pediatrics | 73 (2.4) |

| Neurology | 48 (1.6) |

| Transitional | 43 (1.4) |

| Missing | 27 (0.9) |

Symptom increases

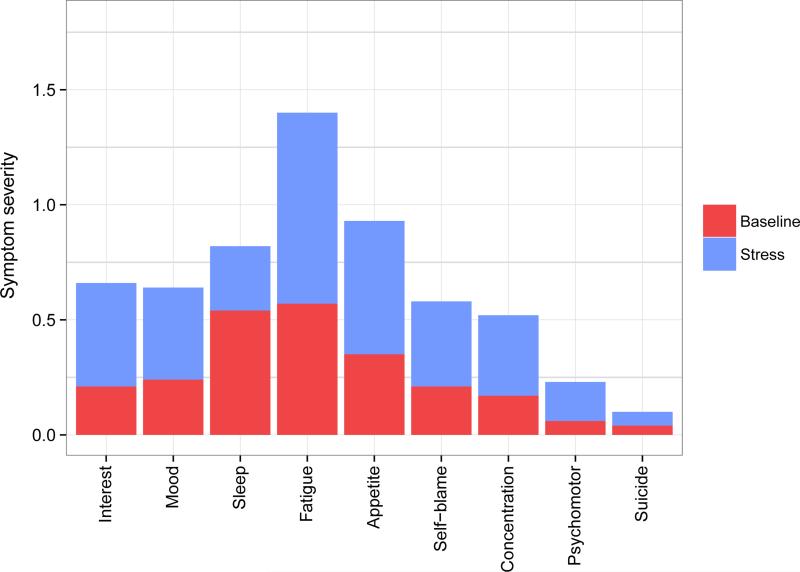

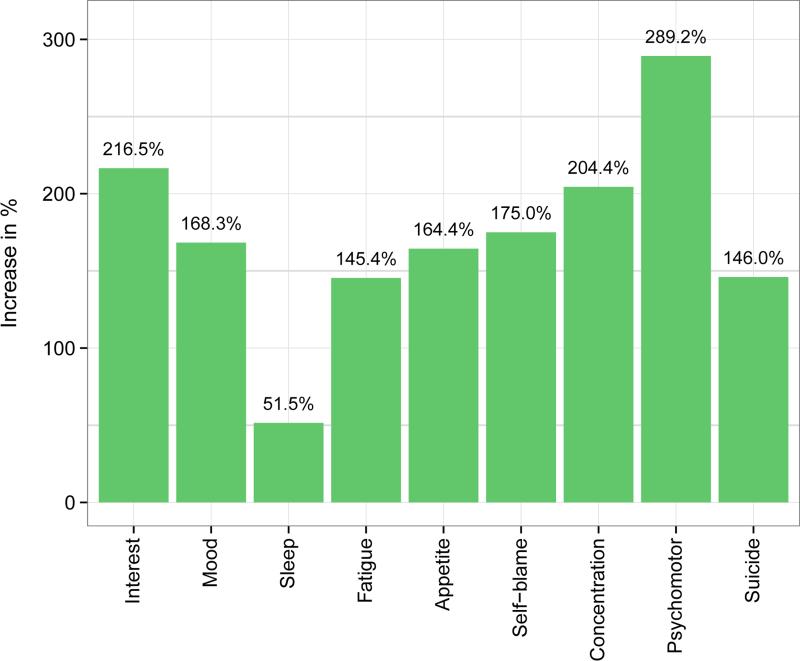

All symptoms increased significantly over time (t-values between 12.3 and 57.6, all p < 0.001) (Table 2) (Figure 1). Symptoms increased by an average of 173.4%, ranging from 51.5% (sleep) to 289.2% (psychomotor) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Symptom severities and increases.

| n = 3,021 | Baseline | Under stress | Increases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | % | p | |

| Interest | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 216.5% | *** |

| Mood | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 168.3% | *** |

| Sleep | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 51.5% | *** |

| Fatigue | 0.57 | 0.69 | 1.40 | 0.70 | 145.4% | *** |

| Appetite | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 164.4% | *** |

| Self-blame | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 175.0% | *** |

| Concentration | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 204.4% | *** |

| Psychomotor | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 289.2% | *** |

| Suicide | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 146.0% | *** |

*p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

p < 0.001, n.s. = not significant.

Fig. 1.

Depression symptoms at baseline and under stress.

Fig. 2.

Symptom change over time.

Symptoms differed in their increases: model I (variable symptom increases across time) fit the data significantly better than model II (equal symptom increases across time) (χ2diff = 2,652, dfdiff = 8, p < 0.001) (Table 3). This means that stress had differential impact on the nine depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

χ2 difference tests for the two model comparisons.

| df | BIC | χ 2 diff | dfdiff | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential symptom change | |||||

| Model Ia | 20 | 275106 | |||

| Model IIb | 12 | 277680 | 2662 | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Differential symptom severity | |||||

| Model Ic | 11 | 137110 | |||

| Model IId | 3 | 150530 | 13502 | 8 | < 0.001 |

df, degrees of freedom; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; χ2diff, χ2 statistic of the χ2 difference test; dfdiff, degrees of freedom of the χ2 difference test; p, p-value of the χ2 difference test

variable symptom increases across time

equal symptom increases across time

variable symptom severities after stress onset

equal symptom severities after stress onset.

Symptoms under stress

Model I (variable symptom severities under stress) showed a superior fit compared to model II (equal symptom severities under stress) (χ2diff = 13,644, dfdiff = 8, p < 0.001) (Table 3). The three symptoms fatigue (Mean = 1.40), appetite (M = 0.93), and sleep (M = 0.82) showed the highest mean severity under stress, while the two symptoms suicide (M = 0.10) and psychomotor (M = 0.23) showed the lowest mean severity.

Discussion

The present study examined the impact of chronic stress on the nine DSM-5 criterion symptoms for depression by prospectively assessing a population of 3,021 individuals before and after the onset of medical internship. While all symptoms increased during internship, the impact of stress varied dramatically across symptoms, with some symptoms increasing substantially more than others; especially psychomotor problems, loss of interest, and concentration problems exhibited pronounced increases. The somatic symptoms fatigue, appetite and sleep problems were most prevalent under stress.

Prior studies have focused on the relationship between stress and depression subtypes, but no clear pattern has emerged (26–28). This inconsistency is likely due to problems pertaining to the validity of MDD subtypes (29,30), a reliance on retrospective self-report of life stress that can be substantially biased (31,32), and a cross-sectional design that confounds the bidirectional influences of life stress and depression (14). The current study addresses these limitations, with a prospective design that allows for a causal interpretation: stress leads to substantial and heterogeneous increases of depressive symptoms.

Implications

The present report documents substantial variability in symptom change across time and symptom severity under stress. This work adds to a growing body of evidence illuminating important differences between individual symptoms of depression (7,10,33), and indicates that the reliance on sum-scores and thresholds obfuscates crucial information about the nature of depressive symptoms. This covert heterogeneity may help to explain recent “disappointing” findings such as low reliability for MDD diagnoses in the DSM-5 field trials (34), low antidepressant efficacy compared to placebo response (35), lack of common genetic markers associated with antidepressant response (36), and failure to detect even small genetic effects with depression diagnosis in large genome-wide association studies (37).

The investigation of individual symptoms reveals clinically useful insights. For instance, about 72 percent of the interns in our study reported sleep problems on at least several days per week under stress. Sleep problems are a well-established predictor for the development of future episodes of depression (38), decrease treatment efficacy (39,40), and directly targeting sleep problems in depressed patients increases overall depression improvement (41,42). We believe that utilizing symptom-information is a crucial step towards the development of more efficient prevention and intervention strategies, and may help us understand underlying biological processes better than diagnosis level analyses.

The DSM criterion symptoms assessed in this study are only a small subset of potential MDD symptoms (43) and were largely determined by clinical consensus instead empirical evidence (12). Various other symptoms, including anxiety, irritability and anger, are prevalent amongst individuals diagnosed with MDD and may have great value in predicting the course of the disease (44,45). Assessing symptoms outside of traditional DSM criteria could advance future studies of stress and depression as well as treatment of patients, and is in line with the National Institute of Mental Health finding that strictly adhering to DSM diagnostic criteria may be inhibiting progress in elucidating the biological roots of mental illness (46). A recent study also documented that specific dimensions of rating scales for depression, such as the 6-item melancholia subscale of the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) (47,48), are more sensitive to treatment response than large multidimensional scales (49). The authors concluded that such subscales may possess greater biological validity and thus circumvent problems of heterogeneity inherent to most depression rating scales.

Limitations

The present report has three limitations. First, we only investigated symptom change in response to one specific stressor. While the particular pattern of symptom change is likely to be different with different stressors, the results of this study and others (50–52) suggest that it is unlikely that other stressors will uniformly increase the prevalence of all depressive symptoms equally. Second, interns are not a representative sample, so extrapolation to the general population should be done with caution. Third, the PHQ-9 neither assesses the direction of depressive symptoms with complex natures (e.g., hypersomnia or insomnia instead of sleep problems) nor MDD symptoms outside of the DSM-5 criteria.

Significant outcomes.

While all MDD symptoms increase in response to internship stress, symptoms differ dramatically in magnitude of increases

MDD symptoms show pronounced prevalence differences under stress.

Limitations

Internship stress is a particular stressor in a fairly homogeneous population, and extrapolation to the general population and other stressors should be done with caution

The present study did not assess the direction of depressive symptoms with complex natures (e.g., hypersomnia vs. insomnia).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Schultze and Dr K. Shedden for their valuable statistical input, and all interns who participated in the study for their kind cooperation. The research leading to the results reported in this paper was sponsored in part by the Cluster of Excellence “Languages of Emotion” (grant no. EXC302) as well as the Research Foundation Flanders (grant no. G.0806.13). Funding was also provided by the NIMH (R01 MH101459, K23 MH095109).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Lichtenberg P, Belmaker RH. Subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:131–5. doi: 10.1159/000286957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister H, Parker JD. Meta-review of depressive subtyping models. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:126–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried EI, Nesse RM. Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 172:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.010. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostergaard SD, Jensen Sow, Bech P. The heterogeneity of the depressive syndrome: when numbers get serious. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:495–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute of Mental Health . Breaking ground, breaking through: The Strategic Plan for Mood Disorders Research (NIH Publication No. 03–5121) National Institutes of Health; USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Neale MC. Evidence for Multiple Genetic Factors Underlying DSM-IV Criteria for Major Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;70:599–607. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myung W, Song J, Lim S-W, Won H-H, Kim S, Lee Y, et al. Genetic association study of individual symptoms in depression. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang KL, Livesley WJ, Taylor S, Stein MB, Moon EC. Heritability of individual depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:125–33. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried EI, Nesse RM, Zivin K, Guille C, Sen S. Depression is more than the sum score of its parts: individual DSM symptoms have different risk factors. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2067–76. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried EI, Nesse RM. The Impact of Individual Depressive Symptoms on Impairment of Psychosocial Functioning. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lux V, Kendler KS. Deconstructing major depression: a validation study of the DSM-IV symptomatic criteria. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1679–90. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazure CM. Life Stressors as Risk Factors in Depression. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1998;5:291–313. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown GW, Harris TO. Depression. In: Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Life Events and Illness. Guilford Press; USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrout PE, Link BG, Dohrenwend BP, Skodol AE, Stueve A, Mirotznik J. Characterizing life events as risk factors for depression: the role of fateful loss events. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;98:460–7. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojo-Moreno L, Livianos-Aldana L, Cervera-Martínez G, Dominguez Carabantes JA, Reig-Cebrian MJ. The role of stress in the onset of depressive disorders. A controlled study in a Spanish clinical sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:592–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0595-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butterfield PS. The stress of residency. A review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1428–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, Speller H, Chan G, Gelernter J, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:557–65. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 1.1-7. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–4.. [Google Scholar]

- 24.IBM Corp . IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21.0. Armonk: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: p. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown GW, Nibhrolchain M, Harris T. Psychotic and neurotic depression: Part 3. Aetiological and background factors. J Affect Disord. 1979;1:195–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschfeld RM. Situational depression: validity of the concept. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:297–305. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy A, Breier A, Doran AR, Pickar D. Life events in depression. Relationship to subtypes. J Affect Disord. 1985;9:143–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melartin T, Leskelä U, Rytsälä H, Sokero P, Lestelä-mielonen P, Isometsä E. Co-morbidity and stability of melancholic features in DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1443. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pae CU, Tharwani H, Marks DM, Masand PS, Patkar AA. Atypical depression: A comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:1023–37. doi: 10.2165/11310990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry B, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Langley J, Silva PA. On the “remembrance of things past”: A longitudinal evaluation of the retrospective method. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raphael KG, Cloitre M. Does mood-congruence or causal search govern recall bias? A test of life event recall. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:555–64. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, Kraemer HC, Kuramoto SJ, Kuhl EA, et al. DSM-5 Field Trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: Test-Retest Reliability of Selected Categorical Diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:59–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pigott HE, Leventhal AM, Alter GS, Boren JJ. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: current status of research. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:267–79. doi: 10.1159/000318293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tansey KE, Guipponi M, Perroud N, Bondolfi G, Domenici E, Evans D, et al. Genetic predictors of response to serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a genome-wide analysis of individual-level data and a meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hek K, Demirkan A, Lahti J, Terracciano A. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Depressive Symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:667–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dew MA, Reynolds CF, Houck PR, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Frank E, et al. Temporal profiles of the course of depression during treatment. Predictors of pathways toward recovery in the elderly. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1016–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pigeon WR, Hegel M, Unützer J, Fan M-Y, Sateia MJ, Lyness JM, et al. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008;31:481–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichstein KL, Wilson NM, Johnson CT. Psychological treatment of secondary insomnia. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:232–40. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rybarczyk B, Lopez M, Benson R, Alsten C, Stepanski E. Efficacy of two behavioral treatment programs for comorbid geriatric insomnia. Psychol Aging. 2002;17:288–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGlinchey JB, Zimmerman M, Young D, Chelminski I. Diagnosing major depressive disorder VIII: are some symptoms better than others? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:785–90. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000240222.75201.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Fiedorowicz JG. Overt Irritability/Anger in Unipolar Major Depressive Episodes: Past and Current Characteristics and Implications for Long-term Course. JAMA psychiatry. 2013;70:1171–80. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:342–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Insel TR. Transforming Diagnosis. [May 21, 2013];National Institute of Mental Health. Available from. 2013 http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml.

- 47.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bech P, Gram L, Dein E, Jacobsen O, Vitger J, Bolwig T. Quantitative Rating of Depressive States. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1975;51:161–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Østergaard SD, Bech P, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Fava M. Brief, unidimensional melancholia rating scales are highly sensitive to the effect of citalopram and may have biological validity: Implications for the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). J Affect Disord. 2014;163:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1521–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keller MC, Nesse RM. The evolutionary significance of depressive symptoms: different adverse situations lead to different depressive symptom patterns. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006 Aug;91:316–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cramer AOJ, Borsboom D, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. The pathoplasticity of dysphoric episodes: differential impact of stressful life events on the pattern of depressive symptom inter-correlations. Psychol Med. 2013;42:957–65. doi: 10.1017/S003329171100211X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]