Abstract

Although social competence in children has been linked to the quality of parenting, prior research has typically not accounted for genetic similarities between parents and children, or for interactions between environmental (i.e., parental) and genetic influences. In this paper, we evaluate the possibility of a gene-by-environment (GxE) interaction in the prediction of social competence in school-age children. Using a longitudinal, multi-method dataset from a sample of children adopted at birth (N = 361), we found a significant interaction between birth parent sociability and sensitive, responsive adoptive parenting when predicting child social competence at school entry (age 6), even when controlling for potential confounds. An analysis of the interaction revealed that genetic strengths can buffer the effects of unresponsive parenting.

Keywords: social competence, parenting, adoption design, GxE interaction

Social competence is a key landmark in child development (Sroufe, 1979) and thus is often the target of empirical research. Although several different approaches to the study of social competence in children have emerged over time (Ladd, 1999), a common definition involves effectiveness in interpersonal interactions (Waters & Sroufe, 1983). Social competence is therefore not simply the absence of behavioral problems, but is comprised of adaptive social characteristics. Within this broad definition, operationalizations of social competence generally refer to specific skills and behaviors, but may also include the attainment of high social status or the quality of interpersonal relationships (Rose-Krasnor, 1997). In this paper, we examine the predictors of social competence in school-age children, with an emphasis on the behavioral aspects of social competence, which include cooperation, communication, responsibility, and self-control in social interactions (Rose-Krasnor, 1997).

Existing research on social competence among school-age children finds that socially competent children are more successful in establishing valuable personal relationships with peers and teachers and, as a result, are able to obtain support from others as needed to attain specific goals, resolve problems, or cope with personal distress (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; Sroufe, 1983). A greater degree of social competence during the transition to school has been found to contribute to a host of beneficial long-term outcomes, including increased academic success and reduced risk of externalizing and internalizing problems (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2010; Burt, Obradović, Long, & Masten, 2008; Ladd et al., 1999; Malecki & Elliot, 2002; Welsh, Parke, Widaman, & O'Neil, 2001). Social skill deficits, in contrast, can trigger a cascade of negative experiences, leading to higher levels of substance use and aggressive behavior in late adolescence (Dodge, Greenberg, & Malone, 2008; Dodge et al., 2009).

Parenting is considered to be a key contributor to the development of social competence in children and adolescents (Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, 2007; Pettit, Dodge, & Brown, 1988). Based on theories of attachment (Bowlby, 1969) and social cognition (Bandura, 1986), contingent parental responsiveness in infancy and childhood is hypothesized to promote the development of internal representations or working models that anticipate interpersonal interactions as a source of pleasure and safety; in contrast, children with a history of rejecting, neglecting, or inconsistent care develop models of others as unresponsive, unreliable, and potentially hurtful (Ainsworth, 1989; Bretherton, 2005; Sroufe, 1988; Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986). Typically, assessment of parental sensitivity and responsiveness includes the tendency to be supportive, affectionate, and aware of the child's needs, to express approval when the child exhibits positive behavior, and to direct positive verbal expressions and positive affect toward the child (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). As children gain more sophisticated cognitive skills during the preschool period, they are able to observe and internalize parents' interpersonal behavior, and these scripts and models are used to guide their behavior in new settings, such as interactions with peers (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999). Thus, parenting that is sensitive and responsive can contribute to higher levels of socially competent behavior and lower levels of incompetent or antisocial behavior in toddlers and school age children (Brody & Flor, 1998; Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992; Hart, Newell, & Olsen, 2003). Similarly, children that rarely experience parental sensitivity and responsiveness have been shown to be less sensitive and less responsive with peers (Lindsey, Mize, & Pettit, 1997). Sensitive and responsive parenting has also been linked to the development of empathy (Zhou et al., 2002) and self-regulation (Brody, Flor, & Gibson, 1999) in children, which in turn support the development of social competence.

Some studies have failed to find a link between parenting and child social competence (e.g., Brody et al., 1999), which raises the question of whether other factors may be in play. One such factor could be shared genes between parent and child, since much of the parenting research has been conducted using biological families. Indeed, research with twins and adopted children has found a substantial genetic basis for many aspects of social behavior (Edelbrock et al., 1995). For example, genetic influences have been found for self-disclosure in social interactions with family, teachers, and peers among both school-aged children and adolescents (Manke, McGuire, Reiss, Hetherington, & Plomin, 1995; Manke & Plomin, 1997; for review see Manke & Pike, 2003). The extant literature also contains examples of research on toddlers and school-age children in which genetic influences explain half or more of the total variance in important precursors to social competence, such as self-regulation (Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997), social relatedness (Van Hulle, Lemery-Chalfant, & Goldsmith, 2007), and sociability (Eid, Riemann, Angleitner, & Borkenau, 2003; Schmitz, Saudino, Plomin, Fulker, & DeFries, 1996); this research mainly used twin designs and questionnaire measures, although Van Hulle et al. (2007) used a parent interview measure. Boivin and colleagues (2013) have also found significant genetic contributions to social difficulties in elementary school as assessed by sociometric nominations and interview data.

In addition to genetic influences on social behavior, research has found a substantial genetic basis for the quality of parenting (Horwitz & Neiderhiser, 2011; Kendler & Baker, 2007; Reiss, Neiderhiser, Hetherington, & Plomin, 2000). For example, studies of parents who were identical or fraternal twins or adoptive siblings suggests that there are genetic effects on self-reports of parenting, including parental warmth (Losoya, Callor, Rowe, & Goldsmith, 1997). Other research has found evocative gene-environment (rGE) effects for both parental warmth and responsiveness (Deater-Deckard, 2000), in which genetic factors were found to play a role in the elicitation of these parenting behaviors. Evidence for evocative rGE has been found for related aspects of parenting, such as parent-child mutuality (Deater-Deckard & O'Connor, 2000). In addition, research has found evidence for evocative rGE effects linking negative parenting and child behavioral problems (Braungart-Rieker, Rende, Plomin, DeFries, & Fulker, 1995; O'Connor, Deater-Deckard, Fulker, Rutter, & Plomin, 1998). These results suggest that there are a variety of mechanisms by which genes could influence parenting and child behavior as well as the link between them.

Notably, there is also evidence for the effects of the environment, rather than genetics, on precursors to and correlates of social competence in toddlers and school-age children, such as positive affectivity (Goldsmith et al., 1997), attachment classification (O'Connor & Croft, 2001), and helping behavior (Volbrecht, Lemery-Chalfant, Akzan, Zahn-Waxler, & Goldsmith, 2007). In addition, Van Hulle and colleagues (2007) found evidence for both genetic and shared environmental influences on a broad assessment of competency in young children (i.e., sustained attention, empathy, imitative play, motivation, and compliance with parents). These findings and those discussed above suggest that the development of social competence in young children may be influenced by both the environment (i.e., parenting) and shared genes, which would be considered an “additive” model. An intriguing possibility is that parenting may interact with inherited qualities when predicting social skill outcomes in children (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002). Although no research exists to support a parenting-by-genetics hypothesis in relation to social competence, the literature does contain evidence that genetic vulnerabilities can be moderated by sensitive, responsive parenting in the development of problem behavior. For example, using an adoption sample, Natsuaki and colleagues (2010) found that responsive parenting moderated the influence of genetic risk factors (as quantified by the presence of major depressive disorder in the birth mother) when predicting infant fussiness. Interaction effects involving parenting and genetic factors have also been found when predicting young children's aggression or problem behaviors (Brendgen et al., 2008a; Brendgen et al., 2008b; Leve et al., 2009). In the molecular genetic literature, a dopamine receptor polymorphism was found to moderate the link between insensitive maternal parenting and externalizing behavior in preschool-aged children (Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van IJzendoorn, 2006), and there is evidence for genetic moderation of the link between parenting and both attachment security (Barry, Kochanska, & Philibert, 2008) and attachment disorganization (Gervai et al., 2007; Spangler, Johann, Ronai, & Zimmerman, 2009) as assessed by the Strange Situation.

In the current study, we examined the main effects of shared genes and environmental (i.e., caregiving) influences, as well as their interaction, when predicting social competence in school-age children. We used an adoption sample in which children were placed in a non-relative adoptive home within the first weeks of life. When design assumptions are met (i.e., no selective placement, and prenatal factors are adequately controlled), the adoption design rules out the possibility of genetic influences due to shared genes between parent and child (i.e., passive rGE). As a marker of genetic influence, we selected birth parent sociability, which not only has a significant genetic component (Eid et al., 2003) but also has been directly linked to the development of social competence (Rubin, Hymel, & Mills, 1989).

Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that early adoptive parenting and birth parent genetic influences would both have significant main effects on child social competence during the transition to school. We also hypothesized that these two predictors would have a significant interaction term, with one predictor moderating the impact of the other. Specifically, we would normally expect insensitive and unresponsive parenting to lead to lower levels of social competence, but genetic advantage could serve as a protective factor, such that high birth parent sociability can promote the development of social competence despite insensitive and unresponsive adoptive parenting. Similarly, sensitive, responsive parenting may serve as a protective factor that promotes the development of social competence even among children at genetic risk due to low birth parent sociability.

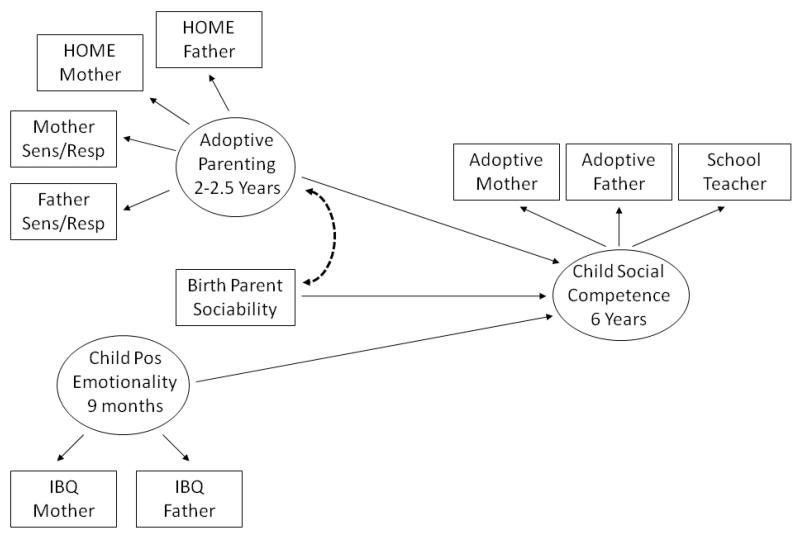

We utilized a multi-method, multi-reporter approach to capture adoptive parenting and children's social competence, and we assessed genetic influences using measures of birth mothers' and fathers' sociability (which, as noted above, has been found to have a significant genetic component and has been linked to the development of social competence). To test for moderation effects on child social competence, we included an interaction term between birth parent sociability and adoptive parenting (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Dashed line represents an interaction term.

As discussed above, an adoption design can eliminate passive rGE effects; however, it cannot account for evocative rGE effects in which an inherited (i.e., genetic) aspect of child personality or behavior elicits a certain kind of parenting. To control for this possibility, we included child positive emotionality in our model (see Figure 1). Previous research has established a genetic link between sociability and positive emotionality (Eid et al., 2003), and positive emotionality could not only influence adoptive parenting, but has also been linked to the development of social competence (Lengua, 2003; Lengua & Kovacs, 2005; Sallquist et al., 2009), suggesting the possibility of an evocative rGE effect. By controlling for child positive emotionality in our analysis, we would be more confident that our genetic (i.e., birth parent sociability) and environmental (i.e., adoptive parenting) effects were independent.

Method

Participants

The current investigation uses families from the Early Growth and Development Study Cohort I (EGDS; Leve et al., 2013). The EGDS is a prospective longitudinal adoption study of children, their adoptive parents, and their birth parents. The EGDS Cohort I (N=361) was drawn from 33 adoption agencies in 10 states from three regions in the United States: the Northwest, West/Southwest, and Mid-Atlantic. The eligibility criteria for including families in the study were the following: (a) the adoption placement was domestic, (b) the infant was placed within 3 months postpartum (M = 7.11 days postpartum, SD = 13.28; median = 2 days), (c) the infant was placed with a non-relative adoptive family, (d) birth and adoptive parents had attained an eighth-grade level or higher level of education, and (e) the infant had no known major medical conditions such as extreme prematurity or extensive medical surgeries. Forty-three percent of the children in the EGDS are female. Fifty-eight percent of the children are Caucasian, 21% are mixed race, 11% are African-American, and 11% are other or unknown. The mean ages of the adoptive mothers, adoptive fathers, birth mothers, and birth fathers at the birth of the child were 38 (SD = 5.5), 38 (SD = 5.8), 24 (SD = 5.9), and 25 (7.2), respectively. More than 90% of the adoptive mothers and fathers were Caucasian. The birth mother and birth father sample, respectively, is 71% and 75% Caucasian, 11% and 9% African-American, 7% and 9% Hispanic, and 11% and 8% multiethnic or unknown. Detailed information regarding sample recruitment, characteristics, and the overall project design is available in Leve et al. (2013). Birth fathers participated in approximately 35% of the families. A comparison of cases revealed that the presence of the birth father in the study was associated with slightly lower scores on adoptive mother-reported child social competence as compared to families where the birth father did not participate (r = −.14, p < .05; R2 = .02); no other significant links were found with any other study variable (15 comparisons overall), which corresponds to the expected Type I error rate (i.e., 5%).

Procedures

Adoptive families were assessed longitudinally during in-person assessments in the families' home that lasted 2 ½ to 4 hrs. In the present study, data from assessments at 9-mo (child positive emotionality), 27-mo (adoptive parenting), and 6 years (child social competence) were included. Birth parents were also assessed longitudinally by means of in-person interviews; data from assessments at 18-mo (sociability) were included in analyses. For both the birth- and adoptive-parent assessments, interviewers asked participants computer-assisted interview questions, and each participant independently completed a set of questionnaires. Adoptive families also participated in tasks in which their behavioral responses were observed and recorded onto digital media. For children enrolled in Kindergarten, questionnaires were mailed to their Kindergarten teachers (upon receiving the consents from the adoptive parents indicating that the teachers could be contacted). Separate teams of interviewers conducted assessments of birth parents and adoptive families such that within each birth parent-adoptive family unit, the interviewer was completely blind to data collected by the other interviewer.

Measures

Child social competence

As noted by Waters and Sroufe (1983), the key to age-appropriate assessment of social competence is to select issues central for the developmental period. We assessed child competence at age 6 using reports of social behavior from adoptive mothers, adoptive fathers, and teachers that were combined into a single latent construct. Adoptive mother and father reports of social competence were measured using the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990). The SSRS can be used with preschool, elementary, and secondary school students. We used the Total Social Skills measure, which includes 39 items (α = .87 for mother ratings and .88 for father ratings) reflecting parent perceptions of child cooperation, communication, responsibility, and self-control in interactions with peers and adults.

Teacher reports of child social competence were measured using the Peer-Preferred Social Behavior subscale of the Walker McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment (Walker & McConnell, 1988). This subscale comprises 17 items (α = .94) reflecting teacher perceptions of the quality of the child's social competence and peer relations. The reports of child social competence from adoptive parents and teachers were moderately correlated (see Table 1), justifying the aggregation of scores across informants into a latent construct.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Data

| Adoptive Parenting |

BP Sociability/Covariates |

Child Social Competence |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 | AM2 | AM3 | AM4 | AF1 | AF2 | AF3 | AF4 | BP Soc | AM PE | AF PE | Adp M | Adp F | Tchr | |

| AM1 | – | |||||||||||||

| AM2 | .29*** | – | ||||||||||||

| AM3 | .29*** | .56*** | – | |||||||||||

| AM4 | .32** | .32*** | .24*** | – | ||||||||||

| AF1 | .21** | .13* | .16** | .04 | – | |||||||||

| AF2 | .07 | .32*** | .32*** | .09 | .37*** | – | ||||||||

| AF3 | .02 | .36*** | .29*** | .16* | .38*** | .66*** | – | |||||||

| AF4 | .08 | .11* | .15* | .38*** | .36*** | .34*** | .33*** | – | ||||||

| BP Soc | −.03 | −.10 | −.08 | −.07 | .02 | −.04 | −.06 | .01 | – | |||||

| AM PE | .04 | −.03 | .07 | .10* | .04 | −.14* | −.11 | .04 | .10 | – | ||||

| AF PE | −.03 | .00 | .08 | .08 | .08 | −.01 | .06 | .05 | .14 | .44*** | – | |||

| Adp M | −.07 | −.03 | .02 | .09 | −.10 | .04 | .02 | −.05 | .10 | .15* | .14* | – | ||

| Adp F | −.01 | −.06 | .02 | −.07 | −.04 | .04 | .01 | −.07 | .13 | .13* | .20** | .45*** | – | |

| Tchr | .09 | .06 | −.05 | .03 | .07 | .10 | .11 | .04 | .04 | −.12 | −.14 | .29** | .29** | – |

| N | 327 | 311 | 311 | 321 | 311 | 298 | 297 | 306 | 302 | 367 | 331 | 250 | 222 | 164 |

| M | 3.89 | 3.75 | 3.69 | 10.68 | 3.82 | 3.59 | 3.53 | 10.24 | −.01 | 5.15 | 5.14 | 52.15 | 50.81 | 65.50 |

| SD | .33 | .49 | .53 | .82 | .40 | .57 | .60 | 1.44 | .95 | .77 | .79 | 8.54 | 8.89 | 12.78 |

Note. AMI = Adoptive Mother Responsiveness (global). AM2 = Adoptive Mother Sensitivity (clean-up task). AM3 = Adoptive Mother Sensitivity (teaching task). AM4 = Adoptive Mother Responsiveness (HOME). AF1 = Adoptive Father Responsiveness (global). AF2 = Adoptive Father Sensitivity (clean-up task). AF3 = Adoptive Father Sensitivity (teaching task). AF4 = Adoptive Father Responsiveness (HOME). BP Soc = Birth parent sociability; AM PE = Adoptive mother-report of positive emotionality; AF PE = Adoptive father-report of positive emotionality; Adp M = Adoptive mother report; Adp F = Adoptive father report; Tchr = Teacher report.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Adoptive parenting

Parenting by adoptive parents was assessed at age 27 months during the in-home assessment. We used two separate observational measures that were combined into a single latent construct. First, we used the Emotional and Verbal Responsiveness subscale of the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Caldwell & Bradley, 1984). Previous research has found that the HOME can predict developmental outcomes in both low-risk and at-risk populations (Elardo & Bradley, 1981; Totsika & Sylva, 2004). The Emotional and Verbal Responsiveness subscale comprises 11 items (α = .59 for mothers and .68 for fathers) reflecting interviewer ratings of emotional and verbal responsiveness (e.g., whether the parent “spontaneously praises child's qualities or behavior”, “responds to child's vocalizations”, “caresses or kisses child”, and whether the parent's voice “conveys positive feeling”).

Second, we used interviewer ratings of parental sensitivity, responsiveness, and guidance during two tasks (clean-up and teaching) in which the child participated separately with each parent. In the first task, the interviewer instructed the parent to have the child clean up all the toys with which they have been playing. In the second task, the interviewer gave the parent and child a puzzle to solve; each parent received a different puzzle of relatively equal difficulty to ensure the child would not solving the same puzzle twice. The parent was instructed to try to let child do the puzzle on her/his own, but to offer any help s/he thought was necessary. The interviewer provided global impressions of overall parental responsiveness across these tasks during the home visit (two items overall, one for each parent) and parental sensitivity and guidance during each task (four items overall, two for each parent and two for each task) using the following scale: very true (1), somewhat true (2), hardly true (3), and not true (4). These items were reverse-coded before analysis so that higher scores indicated greater sensitivity and responsiveness. Interviewers were trained on the rating system prior to going into the field and were instructed that the items should represent their “impressions”, as intended by the original measure (Weinrott, Reid, Bauske, & Brummett, 1981); thus, these data represent an independent assessment by a single individual that is similar to teacher or parent ratings in that regard. Interviewer ratings done in this manner have been shown to correlate with coded observations and child behavioral outcomes in previous research (Weinrott et al., 1981) and have been used in similar ways in other published work (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2012). In general, the measures of adoptive parenting were moderately correlated across informants (see Table 1).

Birth parent sociability

The Sociability subscale of the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ; Evans & Rothbart, 2007) indexed sociability for birth parents. The ATQ is a self-report model of temperament that includes general constructs of effortful control, negative affect, extraversion/surgency, and orienting sensitivity. The Sociability subscale (5 items; α = .72 for birth mothers and .74 for birth fathers) is a component of extraversion/surgency that has been found to be heritable (Eid et al., 2003) and has been directly linked to the development of social competence in children (Rubin et al., 1989). Because the birth mother and father measures of sociability were not significantly correlated (r = .16), the use of both measures in a single latent variable would have resulted in suboptimal model fit; thus, we standardized and averaged the two measures before the analysis (when birth father data were not available, we used birth mother data alone). By averaging the measures from both mother and father, we were able to infer the sum total of the genetic influences as inherited from both parents, which we deemed superior to limiting our analysis to only the maternal measure. However, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we re-analyzed the data using only the maternal measure of sociability in order to evaluate whether our combined approach introduced bias to the results.

Child positive emotionality

We assessed adoptive parent reports of the child's early positive emotionality using the Smiling and Laughter subscale (15 items; α = .83 mothers and .86 fathers) of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Rothbart, 1981) at 9 months. These were expected to be correlated (see Table 1), so we included both adoptive mother and adoptive father reports in a single latent construct.

Other covariates

We assessed prenatal influences and contact between birth and adoptive parents (openness in adoption) as covariates. Prenatal influences were included to control for any pregnancy-related issues that may impact future child functioning and be confounded with genetic influences. A prenatal risk index score was derived using the McNeil–Sjostrom Scale for obstetric complications (McNeil & Sjostrom, 1995) which assesses: (a) maternal/pregnancy complications (including illness, fetal distress during this period, exposure to drugs/alcohol, maternal stress and psychopathology, and psychotropic drug use), (b) labor and delivery complications (prolonged labor, cord complications, interventions needed), and (c) neonatal complications (prematurity, low birth weight). A total score was created by summing across the 3 areas of complications (Marceau et al., 2013).

Openness in adoption was included in the analyses to control for similarities between birth and adoptive families that may have resulted from exchanges between parties. At age 6, we measured the level of openness in adoption using independent reports from adoptive mothers and fathers (for details, see Ge et al., 2008) about perceived openness (a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = very closed to 7 = very open). Mother and father reports were averaged to arrive at the final score (r = .73, p < .001).

Analysis Plan

To estimate the size of main effects independent of covariates, we initially fit a model with only birth parent sociability, adoptive parenting, and child social competence. Next, we added child positive emotionality and covariates and re-fit the model. Both prenatal influences and openness in adoption were found to be uncorrelated with the other variables in the model and were removed from further consideration. Finally, we created an interaction term between adoptive parenting and birth parent sociability in order to test for the possibility of moderation effects; as adoptive parenting was a latent construct and birth parent sociability was a combination of standardized variables, both components of the interaction term were already centered. If significant results were found for the interaction term, we then calculated regions of significance (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006), which define the specific values of one predictor (z) at which the regression of the outcome (y) on the other predictor (x) moves from non-significance to significance.

Because our adoptive parenting construct contained multiple measures from different sources on different individuals (i.e., mother and father), we considered it to be Multitrait-Multimethod (MTMM) data, and thus explicitly accounted for the likelihood that measures involving the same individual or using the same method may correlate more highly with one another than with the rest of the measures within the latent construct (Kenny, 1976; Marsh, 1989; Saris & Aalberts, 2003). Specifically, we allowed the error terms for measures of parenting by the adoptive mother to correlate with one another (and similarly for the adoptive father), and we also allowed the error terms for the different measurement instruments to correlate (e.g., the HOME). We then evaluated whether these correlations contributed significantly to model fit; if not, they were discarded. In reporting the results, we specified the correlations that were retained. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which all correlations were removed and the models were re-fit to determine whether the correlations had a significant impact on the results.

To fit the models, we used structural equation modeling in Mplus 6.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008). We used robust maximum likelihood analysis, which can provide unbiased estimates in the presence of both missing data and non-normality (e.g., our HOME measures were negatively skewed). When available, standard measures of fit are reported, including the chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), nonnormed or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI values greater than .95, TLI values greater than .90, RMSEA values less than .05, and a nonsignificant χ2 (or a ratio of χ2/df < 3.0) indicate good fit (Bentler, 1990; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Item correlations and descriptive data are presented in Table 1. We did have a degree of missing data, but an analysis revealed that missingness in later waves (e.g., social competence) was not systematically related to variable values in earlier waves (e.g., adoptive parenting; no significant correlations out of 24). In addition, missingness in our key constructs (i.e., parenting, sociability, and social competence) was not related to family income (no significant correlations out of 16) or marital status (one significant correlation out of 16). However, we did find an indication of systematic attrition when considering ethnicity; in our sample, European-American birth and adoptive parents were somewhat more likely to have missing data as compared to non-European-Americans (four significant correlations out of 16). Thus, we conducted two additional analyses: (1) we examined whether the use of ethnicity as a predictor would alter the model results, and (2) we examined ethnicity as a moderator of model paths.

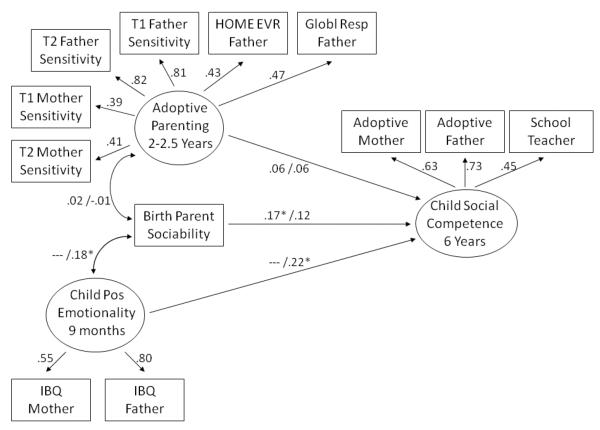

Our initial model contained birth parent sociability, adoptive parenting, and child social competence. Factor loadings were adequate except for the adoptive mothers' measure of “responsiveness” (loading = .22) and the Responsiveness subscale of the HOME (loading = .24), which were removed from the model. All measures of child social competence demonstrated adequate loadings (> .30). The only MTMM correlation retained was between the adoptive father measures of sensitivity and guidance in the teaching and clean-up tasks (r = .49, p < .001). Model fit was good, χ2(33) = 34.72, ns, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .012 (95% CI: .000|.041). Adoptive parenting was not a significant predictor of child social competence (β = .06, ns), but birth parent sociability was a significant predictor (β = .17, p < .05; see Figure 2). These results did not vary when the MTMM correlation was removed, nor did they change when the two measures of adoptive mother parenting were re-added to the latent construct.

Figure 2.

Fitted model. T1 = Task 1 (teaching). T2 = Task 2 (clean-up). EVR = Emotional and Verbal Responsiveness subscale of HOME. Globl Resp = Global rating of responsiveness during parenting tasks. Betas for adoptive parenting and birth parent sociability predicting social competence are presented without/with the inclusion of child positive emotionality.

We then inserted child positive emotionality and re-fit the model. Model fit was good, χ2(50) = 65.80, ns, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .029 (.000|.046). In this model, child social competence was significantly predicted by child positive emotionality (β = .22, p < .05), and the previous prediction by birth parent sociability was reduced to non-significance (β = .12, ns; see Figure 2). Birth parent sociability was significantly correlated with child positive emotionality (β = .18, p < .05) as would be expected. These results did not change when the MTMM correlation was removed, nor did they change when the two measures of adoptive mother parenting were re-added.

Finally, we added the interaction term between adoptive parenting and birth parent sociability. The interaction term was significant (B = −7.29, SE = 3.63, p < .05; no standardized betas or model fit indices were provided by Mplus). The residual variance of the latent construct representing social competence decreased from 26.09 in the previous model to 24.31 (p < .01), suggesting that the interaction term explained an additional 7% of the variance. Our results did not change when the MTMM correlation was removed, nor did they change when the two measures of adoptive mother parenting were re-added. These results also did not change when we added ethnicity as a predictor, and in a separate analysis, ethnicity did not act as a moderator, χ2(4) = 5.22, ns. Finally, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis using only birth mother sociability, and the interaction effect was still significant, B = −5.95, SE = 2.60, p < .05.

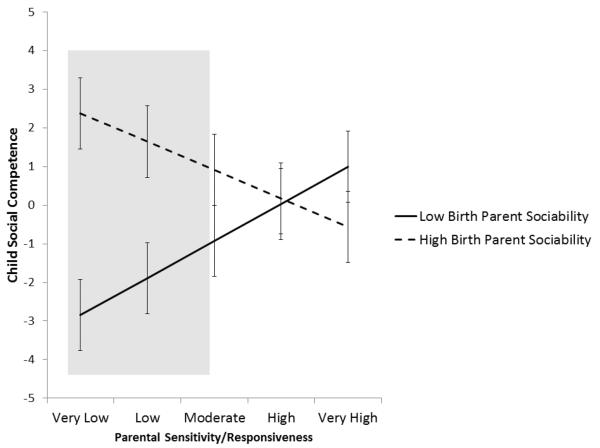

To explore the interaction term, we graphed the predicted values for child social competence in situations of low and high birth parent sociability (one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively) and various levels of adoptive parent sensitivity and responsiveness (i.e., low sensitivity/responsiveness was 1 and 2 SD below the mean, whereas high sensitivity/responsiveness was 1 and 2 SD above the mean; Aiken & West, 1991; see Figure 3). The graph includes 95% confidence intervals for each data point. An examination of the graph suggests that the relationship between parenting and social competence differs as a function of birth parent sociability. In situations of low and very low adoptive parent sensitivity and responsiveness (i.e., the left half of the figure), children with high birth parent sociability were predicted to have a higher degree of social competence when compared to children of low birth parent sociability. In contrast, high and very high adoptive parent sensitivity and responsiveness predicted fairly uniform levels of social competence regardless of birth parent sociability (i.e., the right half of the graph); the confidence intervals overlapped in this area of the graph, so we can assume that there were no significant differences in child social competence for low as compared to high birth parent sociability.

Figure 3.

Graph of interaction; shaded area represents region of significance.

To verify this interpretation, we calculated the regions of significance. Considering adoptive parenting to be the moderator, we found that the link between birth parent sociability and social competence became significant and positive at moderate levels of parenting sensitivity and responsiveness (i.e., −.06, just below the mean of zero; see Figure 3; simple slope = 1.14, SE = .58, p = .05). The link between sociability and social competence was negative at extremely high levels of sensitivity/responsiveness (i.e., .72, more than 4 SD above the mean) that were highly unlikely to be attained (this area is not represented in Figure 3). In between these points (i.e., at high or very high levels of sensitivity/responsiveness), the link between sociability and social competence was non-significant. In other words, in situations of environmental risk (i.e., unresponsive parenting), genetic influences from biological parents can serve as a protective factor and promote the development of social competence. Similarly, we can also view sensitive/responsive parenting as a protective factor, promoting the development of social competence in situations of genetic risk (i.e., low birth parent sociability).

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that both genetic influences and adoptive parenting in early childhood would be associated with child social competence during the transition to school, and that the two would have interactive effects on child social competence. Prior to entering the covariates and interaction term, birth parent sociability predicted child social competence, suggesting a genetic main effect transmitted in the form of an inherited tendency to be sociable. However, once the covariates were included in the model, the effect of birth parent sociability was reduced to nonsignificance and toddler positive emotionality emerged as a key predictor of child social competence, which echoes other findings suggesting that positive emotionality is an important precursor to social competence (Lengua, 2003; Lengua & Kovacs, 2005; Sallquist et al., 2009). Toddler positive emotionality and birth parent sociability were significantly correlated in our model (see Figure 2), which corresponds to previous research that found a common genetic component for the two constructs (Eid et al., 2003); this correlation may also explain why the main effect of birth parent sociability was attenuated in this model.

When the interaction term between sensitive parenting and birth parent sociability was added to the model, it significantly predicted child social competence, suggesting a GxE effect. As seen in Figure 3, social competence was significantly lower among children with genetic vulnerabilities (i.e., birth parents that reported lower levels of sociability) whose adoptive parents demonstrated lower levels of sensitive, responsive parenting; in contrast, children of birth parents who were higher in sociability were not negatively impacted by the lack of sensitive, responsive parenting. This finding suggests that higher levels of birth parent sociability can confer a degree of inherited “resilience” in children, or a degree of protection against less responsive caregiving environments. On the opposite end of the continuum, there is evidence that children who received sensitive, responsive parenting were not negatively impacted by low levels of birth parent sociability; from this point of view, responsive parenting can be seen as a protective factor against genetic vulnerability. Although the graph of the interaction term suggested that responsive parenting could potentially be harmful for children with high birth parent sociability, the region of significance suggested that the attainment of this condition was extremely unlikely. Thus, it would be inappropriate to interpret this particular aspect of our findings.

These results add to the sparse literature examining GxE interactions in child development. In this study, inherited genetic advantage was found to buffer against low-quality parenting; it is only when both genetic influences and environments were below average that adverse effects were transmitted to the child. Given that previous research on GxE interactions in young children has focused on outcomes such as fussiness (Natsuaki et al., 2010) and problem behavior (Leve et al., 2009), the current study provides initial evidence suggesting that genetic influences can offset an environmental liability when predicting prosocial behavior. The adoption design methodology makes this finding particularly relevant for adoptive parents; rather than experiencing only concern over any birth parent problems or deficits, adoptive families can be reassured that genetic strengths are also transmitted to children. Relatedly, our results suggest that high-quality parenting can compensate for genetic liabilities related to social competence.

It was somewhat surprising that we did not find evidence for a main effect of sensitive parenting on child social competence, since prior work with school-age children has shown significant associations (Elicker et al., 1992; Hart et al., 2003). However, other research has failed to find such a link (Brody et al., 1999) and as noted above, many of the existing studies are comprised of genetically-related parents and children, so our failure to find a significant link may be due to the nature of our sample (i.e., adopted children). The parenting measures used in this study may also have played a role in our results; although observational measures are generally considered to be among the strongest approaches to assessing parenting with young children, it is possible that our interviewer impressions underestimated the effects of parenting to an unknown extent. Replication of our results using more robust assessments of parenting would help to clarify this aspect of our findings.

In general, our results are strengthened by our adoption design, which removed shared genetic influence as a potential confounding factor and enabled us to focus on genetic and environmental influences (and their interaction) on behavior. Additional strengths include the longitudinal approach, the multi-method, multi-reporter data, and the use of additional controls such as positive emotionality to address the possibility of evocative rGE effects. We also evaluated measures of prenatal effects and the adoption process to establish that neither had a significant impact on the variables of interest.

Limitations and conclusion

This study possesses limitations that should temper the interpretation of the results. One area of concern was the degree of missing data (see Table 1) and link between patterns of missingness and ethnicity (see Results). However, our additional analyses incorporating ethnicity suggested that the pattern of missingness did not introduce significant bias into the results. We also found a few issues related to model fit; two parenting variables were dropped, and an MTMM correlation was required to ensure good model fit. However, our results did not change when the parenting variables were re-introduced to the model and the MTMM correlation was removed, suggesting that they did not create significant bias. Third, the internal consistency for the maternal HOME data was sub-optimal. Although internal consistency isn't always reported in developmental studies, psychometric research using the HOME (e.g., Bradley & Caldwell, 1979; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Cabrera, 2004) has previously reported levels of internal consistency similar to ours (i.e., .60 or less), suggesting that it may be inherent in the measure to some extent. In any case, our sensitivity analysis found that including and excluding the maternal HOME data did not alter the results, so this issue did not appear to introduce bias to the results. Fourth, our measures of maternal and paternal birth parent sociability were not correlated, so we could not include both in a latent construct without negatively impacting model fit. Thus, we standardized and combined the two measures to ensure we were representing the full “genetic load” inherited by the child. As reported in the Results section, usage of the maternal measure alone did not alter the findings, suggesting that our approach did not introduce bias. Finally, the children in our sample were primarily residing in middle class families, and it is unknown whether a similar pattern of findings would be identified in children residing in lower income families or high risk neighborhoods.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that a high degree of sociability in birth parents can confer a degree of resilience to children, where the lack of sensitive, responsive parenting does not prevent a child from becoming socially competent with peers. Similarly, we found that sensitive, responsive parenting can serve as a protective factor for genetically vulnerable children and encourage the development of social competence despite genetic risk. These results provide a needed degree of clarity regarding the relationship among genes, environment, and social competence during early childhood.

Our results also have implications for prevention. Genetic variation has been found to influence how individuals and families respond to parent-based prevention programs that target child externalizing behavior (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Pijlman, Mesman, & Juffer, 2008) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (van den Hoofdakker et al., 2012). In addition, programs targeting behavior in older children have found evidence for genetic moderation of effects of improved parenting on adolescent substance use (Brody et al., 2014). Interestingly, genetic variation may also influence the responsiveness of individuals to one type of prevention programming as compared to others (Bauer et al., 2007). Overall, these findings, and ours, suggest that (1) genetic risk can be ameliorated by environmental factors, which in turn can be targeted by specific prevention programs; and, (2) exploring links among environmental and genetic influences on behavior can be a productive strategy for strengthening the effects of existing prevention programs by identifying particularly vulnerable and/or responsive populations. Future research could examine GxE effects on a wider variety of positive outcomes at different ages, which could not only add to our understanding of child development and but also highlight new opportunities for prevention and intervention.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by R01 HD042608 from NICHD, NIDA, and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1–5: David Reiss; PI Years 6–10: Leslie Leve); R01 DA020585 from NIDA, NIMH and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jenae Neiderhiser); and R01 MH092118 (PIs: Jenae Neiderhiser and Leslie Leve) from NIMH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to thank the birth parents and adoptive families who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who helped with the recruitment of study participants. We gratefully acknowledge Rand Conger, John Reid, Xiaojia Ge, Jody Ganiban, and Laura Scaramella for their contributions to the larger study.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH. Gene?environment interaction of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) and observed maternal insensitivity predicting externalizing behavior in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology. 2006;48:406–409. doi: 10.1002/dev.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Pijlman FT, Mesman J, Juffer F. Experimental evidence for differential susceptibility: dopamine D4 receptor polymorphism (DRD4 VNTR) moderates intervention effects on toddlers' externalizing behavior in a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:293–300. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barry RA, Kochanska G, Philibert RA. GxE interaction in the organization of attachment: Mothers' responsiveness as a moderator of children's genotypes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1313–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Covault J, Harel O, Das S, Gelernter J, Anton R, Kranzler HR. Variation in GABRA2 predicts drinking behavior in project MATCH subjects. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1780–1787. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Dionne G, Girard A, Pérusse D, Tremblay RE. Strong genetic contribution to peer relationship difficulties at school entry: Findings from a longitudinal twin study. Child Development. 2013;84:1098–1114. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Haynes OM. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and psychopathology. 2010;22:717. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1 Attachment. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Caldwell BM. Home observation for measurement of the environment: a revision of the preschool scale. American journal of mental deficiency. 1979;84:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker J, Rende RD, Plomin R, DeFries JC, Fulker DW. Genetic mediation of longitudinal associations between family environment and childhood behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM, Dionne G, Tremblay RE, Pérusse D. Linkages between children's and their friends' social and physical aggression: Evidence for a gene–environment interaction? Child Development. 2008a;79:13–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Girard A, Dionne G, Pérusse D. Gene–environment interaction between peer victimization and child aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2008b;20:455–471. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. In pursuit of the internal working model construct and its relevance to attachment relationships. In: Grossmann KE, Grossmann K, Waters E, editors. Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies. Guilford; New York: 2005. pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Beach SR, Kogan SM, Yu T, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Windle M, Philibert RA. Differential sensitivity to prevention programming: A dopaminergic polymorphism-enhanced prevention effect on protective parenting and adolescent substance use. Health Psychology. 2014;33:182–191. doi: 10.1037/a0031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL, Gibson NM. Linking maternal efficacy beliefs, developmental goals, parenting practices, and child competence in rural single parent African American families. Child Development. 1999;70:1197–1208. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman LM, Gouley KK, Chesir-Teran D, Dennis T, Klein RG, Shrout P. Prevention for preschoolers at high risk for conduct problems: Immediate outcomes on parenting practices and child social competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:724–734. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradović J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79:359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Administration Manual, Revised Edition, Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. University of Arkansas; Little Rock, AR: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Kerr DCR, Owen LD, Kim HK. Growth in externalizing and internalizing problems in childhood: A prospective study of psychopathology across three generations. Child Development. 2012;83:1945–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting and child behavioral adjustment in early childhood: A quantitative genetic approach to studying family processes. Child development. 2000;71:468–484. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, O'Connor TG. Parent–child mutuality in early childhood: Two behavioral genetic studies. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:561–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79:1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74:vii–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbrock C, Rende R, Plomin R, Thompson LA. A twin study of competence and problem behavior in childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:775–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid M, Riemann R, Angleitner A, Borkenau P. Sociability and positive emotionality: Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariation between different facets of extraversion. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:319–346. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7103003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elardo R, Bradley RH. The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Scale: A review of research. Developmental Review. 1981;1:113–145. [Google Scholar]

- Elicker J, Englund M, Sroufe LA. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships. In: Parke RD, Ladd GW, editors. Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Development of a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:868–888. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KC. Does child temperament moderate the influence of parenting on adjustment? Developmental Review. 2002;22:623–643. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Martin DM, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Villareal G, Scaramella L, Reid JB, Reiss D. Bridging the divide: Openness in adoption and postadoption psychosocial adjustment among birth and adoptive parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:529–540. doi: 10.1037/a0012817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervai J, Novak A, Lakatos K, Toth I, Danis I, Ronai Z, et al. Infant genotype may moderate sensitivity to maternal affective communications: Attachment disorganization, quality of care, and the DRD4 polymorphism. Social Neuroscience. 2007;2:307–319. doi: 10.1080/17470910701391893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Buss KA, Lemery KS. Toddler and childhood temperament: Expanded content, stronger genetic evidence, new evidence for the importance of environment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:891–905. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Rating System Manual. NCS Pearson, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, Newell LD, Olsen SF. Parenting skills and social-communicative competence in childhood. In: Greene JO, Burleson BR, editors. Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 753–797. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz BN, Neiderhiser JM. Gene–environment interplay, family relationships, and child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:804–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: A systematic review. Psychological medicine. 2007;37:615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. An empirical application of confirmatory factor analysis to multitrait-multimethod matrix. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1976;12:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual review of psychology. 1999;50:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G, Birch S, Buhs E. Children's social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Associations among emotionality, self-regulation, adjustment problems, and positive adjustment in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:595–618. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Kovacs EA. Bidirectional associations between temperament and parenting and the prediction of adjustment problems in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Patterson G. Refining intervention targets in family-based research: Lessons from quantitative behavioral genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:516–526. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw D, Scaramella LV, Reiss D. Structured parenting of toddlers at high versus low genetic risk: Two pathways to child problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1102. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b8bfc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D. The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16:412–423. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey EW, Mize J, Pettit GS. Mutuality in parent-child play: Consequences for children's peer competence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:523–538. [Google Scholar]

- Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Cabrera N. The home observation for measurement of the environment (HOME) inventory: The derivation of conceptually designed subscales. Parenting. 2004;4:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Losoya SH, Callor S, Rowe DC, Goldsmith HH. Origins of familial similarity in parenting: A study of twins and adoptive siblings. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1012–1023. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, Elliot SN. Children's social behaviors as predictors of academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002;17:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Manke B, McGuire S, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, Plomin R. Genetic contributions to adolescents' extrafamilial social interactions: Teachers, best friends, and peers. Social Development. 1995;4:238–256. [Google Scholar]

- Manke B, Pike A. Combining the Social Relations Model and behavioral genetics to explore the etiology of familial interactions. Marriage & Family Review. 2003;33:179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Manke B, Plomin R. Adolescent familial interactions: A genetic extension of the social relations model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Hajal N, Leve LD, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Ganiban JM, Mayes LC, Neiderhiser JM. Measurement and associations of pregnancy risk factors with genetic influences, postnatal environmental influences, and toddler behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2013;37:366–375. doi: 10.1177/0165025413489378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW. Confirmatory factor analysis of multitrait-multimethod data: Many problems and few solutions. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1989;13:335–361. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil T, Sjostrom K. McNeil-Sjostrom Scale for obstetric complications. Lund University; Malmö, Sweden: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Ge X, Leve L, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, Reiss D. Genetic liability, environment, and the development of fussiness in toddlers: The roles of maternal depression and parental responsiveness. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1147–1158. doi: 10.1037/a0019659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG, Croft CM. A twin study of attachment in preschool children. Child Development. 2001;72:1501–1511. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG, Deater-Deckard K, Fulker D, Rutter M, Plomin R. Genotype-environment correlations in late childhood and early adolescence: Antisocial behavioral problems and coercive parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:970–981. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Brown MM. Early family experience, social problem solving patterns, and children's social competence. Child Development. 1988:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Neiderhiser J, Hetherington EM, Plomin R. The relationship code: Deciphering genetic and social influences on adolescent development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L. The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development. 1997;6:111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development. 1981;52:569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hymel S, Mills RS. Sociability and social withdrawal in childhood: Stability and outcomes. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:237–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallquist JV, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Reiser M, Hofer C, Liew J, Zhou Q, Eggum N. Positive and negative emotionality: Trajectories across six years and relations with social competence. Emotion. 2009;9:15–28. doi: 10.1037/a0013970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saris WE, Aalberts C. Different explanations for correlated disturbance terms in MTMM studies. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz S, Saudino KJ, Plomin R, Fulker DW, DeFries JC. Genetic and environmental influences on temperament in middle childhood: Analyses of teacher and tester ratings. Child Development. 1996;67:409–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. The coherence of individual development: Early care, attachment, and subsequent developmental issues. American Psychologist. 1979;34:834–841. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Infant-caregiver attachment and patterns of adaptation in preschool: The roots of maladaptation and competence. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota symposium in child psychology. Vol. 16. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. pp. 41–91. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. The role of infant-caregiver attachment in development. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical implications of attachment. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA. One social world: The integrated development of parent-child and peer relationships. In: Collins WA, Laursen B, editors. Relationships as developmental contexts: The Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. Vol. 30. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Fleeson J. Attachment and the construction of relationships. In: Hartup W, Rubin Z, editors. Relationships and Development. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1986. pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Spangler G, Johann M, Ronai Z, Zimmerman P. Genetic and environmental influence on attachment disorganization. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:952–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika V, Sylva K. The home observation for measurement of the environment revisited. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2004;9:25–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-357X.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoofdakker BJ, Nauta MH, Dijck-Brouwer DAJ, van der Veen-Mulders L, Sytema S, Emmelkamp PMG, Minderaa RB, Hoekstra PJ. Dopamine transporter gene moderates response to behavioral parent training in children with ADHD: A pilot study. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:567–574. doi: 10.1037/a0026564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle CA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Goldsmith HH. Genetic and environmental influences on socio-emotional behavior in toddlers: An initial twin study of the infant–toddler social and emotional assessment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1014–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volbrecht MM, Lemery-Chalfant K, Akzan N, Zahn-Waxler C, Goldsmith HH. Examining the familial link between positive effect and empathy development in the second year. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2007;168:105–130. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.2.105-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HM, McConnell SR. The Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment. Pro-Ed; Austin, TX: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Sroufe LA. Social competence as a developmental construct. Developmental review. 1983;3:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Weinrott MR, Reid JB, Bauske BW, Brummett B. Supplementing naturalistic observations with observer impressions. Behavioral Assessment. 1981;3:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh M, Parke RD, Widaman K, O'Neil R. Linkages between children's social and academic competence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:463–481. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Cumberland AJ, Shepard S. The relations of parental warmth and positive expressiveness to children's empathy-related responding and social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 2002;73:893–915. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]