Abstract

Many patients and health care providers lack awareness of both the existence of, and treatments for, lingering distress and disability after treatment. A cancer survivorship wellness plan can help ensure that any referral needs for psychosocial and other restorative care after cancer treatment are identified.

As a consequence of continuing advances in the detection and treatment of cancer at all stages of the disease, there are now more than 13 million cancer survivors in the U.S.; 500,000 of them received health care services in the VHA.1,2 Given this shifting trajectory of survivorship, for many patients, cancer is better understood as a chronic illness. As such, ongoing care after cancer treatment has assumed greater significance.

This article describes the bio-psychosocial needs of cancer survivors and discusses the development of a VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) survivorship care plan (SCP) that includes a wellness plan to guide patient care. The description of cancer survivors relies on the literature as well as on the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vetcares) of 170 veterans diagnosed with oral and digestive cancers (ie, head and neck, gastric/ esophageal, colorectal) who were interviewed at 6, 12, and 18 months after their diagnosis (described in detail elsewhere).3

PSYCHOSOCIAL DISTRESS AFTER CANCER

A cancer diagnosis is usually received suddenly and unexpectedly. Cancer continues to be the most commonly feared diagnosis; receiving the diagnosis can be traumatic. Treatments can be harsh and significantly disrupt daily life. After the physical rigors of treatment subside, depression and anxiety may emerge as the impact of diagnosis and treatment are processed.

Depression

After cancer treatment, approximately 1 in 4 individuals meets criteria for depression.4,5 Depression frequently results in significant additional disability in survivors. The risk for depressive symptoms is highest in the first year following treatment. Studies conflict about whether the risk for depression continues to be greater in long-term cancer survivors or is equal to that in the general population, but in the Vetcares sample, 18% continued to exceed a standard rating scale cutoff for major depression at 18 months postdiagnosis (Table 1).6–8

Table 1.

Psychosocial Distress Reported By a Sample of Veterans After Cancer Treatment

| Domain | % Distressed | Scale mean(standard deviation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mo | 18 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | F | |

| Depression | 27 | 18 | 6.8 (7.0) | 5.6 (6.0) | 5.2 (5.8) | 8.77a |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 12 | 9 | 30.2 (14.2) | 28.0 (12.7) | 27.7 (13.4) | 18.99a |

| Worry | 25 | 17 | 27.0 (23.4) | 25.0 (22.8) | 21.0 (21.4) | 10.98a |

Anxiety

Many individuals report symptoms of cancer-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the first year following cancer treatment.9 Approximately 1 in 10 meets the criteria for PTSD, although longitudinal studies are lacking.10 In the Vetcares sample, 80% experienced at least 1 symptom of cancer-related PTSD, and 10% exceeded a standard rating scale cutoff for PTSD.11 In a veteran population, concurrent combat PTSD may be associated with cancer PTSD; 36% of the Vetcares sample said cancer reminded them of combat, and 23% said dreams of combat became more frequent during cancer.12 In addition to the intrusive symptoms of cancer-related stress, fears of recurrence are common.13 In the Vetcares study, veterans reported fear of recurrence, worries about family, health and health care, and existential concerns (eg, “Am I making the most of the time I have?”).14

Social Interference

Long-term adverse effects of cancer, when untreated, decrease the capacity for work and create social strain.15–17 This veteran sample reported that cancer interfered with marital and family relationships (45%), social and recreational activities (43%), work (46%), and finances (37%).18 Restrictions on socialization may be especially problematic, given that social support is a critical predictor of coping ability during the process of cancer diagnosis and treatment.19,20

FUNCTIONAL DISABILITY AFTER CANCER

Cancer treatment may involve removal of the breast, prostate, bladder, colon, esophagus, or other body part and, as a result, may be accompanied by changes in physical function. In addition, persistent toxicities of chemotherapy and radiation therapy across organ systems may lead to diffuse problems.

Neuropsychiatric Disability (Cognition, Insomnia, Fatigue)

Cognitive problems with speed of processing, short-term memory, spatial abilities, and word finding have been noted across cancer types, although the extent of impairment varies, depending on treatments.21,22 In the Vetcares population, an astounding 1 in 2 experienced impaired cognition (<26 adjusted Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] score),23 while nearly 1 in 3 reported significant insomnia or fatigue via the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (Table 2).24

Table 2.

Functional Disability Reported By a Sample of Veterans After Cancer Treatment

| Function | % Impaired | Scale mean (standard deviation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mob | 18 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | F | |

| Insomnia | 25 | 10 | 10.7 (4.8) | 9.7 (4.6) | 9.5 (4.3) | 7.26a |

| Fatigue | 28 | 13 | 10.3 (4.9) | 9.5 (4.3) | 9.3 (4.6) | 9.95a |

| Mobilityc | 45 | 28 | 15.3 (4.7) | 15.7 (4.5) | 16.2 (4.7) | 9.66a |

| Pain | 31 | 30 | 8.6 (5.5) | 8.49 (5.1) | 8.7 (5.4) | 21.39a |

P < .01.

For Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) subscales, “impairment” is defined as scoring at the 16th percentile or less.

Reverse-scored (higher is better).

Musculoskeletal Disability (Physical Function, Pain)

Physical impairments in strength, range of motion, and balance may be associated with generalized treatments like chemotherapy and with targeted treatments such as major surgical resections. Older cancer survivors may have more functional disability than do younger survivors; in the Vetcares sample, about 1 in 2 described problems with physical function (eg, difficulty doing chores, climbing stairs, walking, shopping).25,26 Pain is common during cancer treatment and may continue after treatment is completed; 1 in 3 in the Vetcares sample continued to report significant pain 18 months after diagnosis.27,28 Causes are multifactorial, such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy or postsurgical syndromes.29

Other Disabilities

In addition to neuropsychiatric and musculoskeletal impairments, a wide range of other functional limitations are found, depending on the cancer and its treatment. Sexual complaints, which should not be confused with lack of interest, are one of the most prevalent, long-term complications of cancer.30 In the Vetcares sample, almost half (43%) the veterans stated that their sex lives were worse than they were before cancer, yet 73% said that their interest in sex was the same or stronger. In addition, disruption in gastroenterological function is common, with both weight loss and weight gain.31 Other functional challenges may include difficulties with speech, swallowing, and for patients who have them, difficulties with mechanical devices (eg, a feeding tube) and stoma care.17,32 Bladder and bowel functions may be affected as well.33–35

HEALTH CARE AFTER CANCER

Oncology research has resulted in remarkable strides in the development of treatments that extend life. After cancer treatment, oncologists focus appropriately on ongoing surveillance for recurrence. However, many patients, and possibly some health care professionals, lack awareness of both the existence of, and treatments for, lingering distress and disability after treatment.36,37

For example, one Vetcares patient said he wished his physicians had prepared him for his symptoms after treatment. “[I wish the doctors would say]…‘It may take a while, but you may recover…’ I was never talked to about how life would be afterwards—not just physical, but your life.” He expressed a wish for “…a phone call every few weeks to check in…I sort of navigated it myself.” The lack of awareness and preparation for the chronic care needs of cancer survivors may be a relic of the discontinuity between specialty oncology services and primary care delivery before and after acute cancer care.

With its integration of inpatient and outpatient services across primary and specialty care, VHA is a leading-edge provider of comprehensive cancer survivorship care. To ensure that VHA is meeting the chronic care needs of the veterans who are cancer survivors, assessment and treatment planning services, in addition to including traditional screening and surveillance programs, should also be aligned with survivors’ biopsychosocial needs.

The Survivorship Care Plan

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), recognizing the need for treatment of both psychosocial distress and functional disability after cancer treatment, released the report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition,31 in 2005, followed in 2008 by Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs.38 An SCP has been proposed to document patient and provider awareness of the need for postcancer treatment rehabilitation, broadly conceived, and to direct patients to appropriate referrals.29

Ideally, an SCP provides (1) a summary of cancer treatment; (2) a plan for surveillance and preventive care; and (3) recommendations for rehabilitative care (although the latter are often missing). The SCP has been widely embraced by patient groups and by the American Society of Clinical Oncologists. The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons proposed a new accreditation standard, to begin in 2015, which will require “a process to disseminate a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan to patients with cancer who are completing cancer treatment.”39 While the SCP is a promising tool, it may facilitate survivorship care best when it is patient centered—that is, when it is used to elicit and personalize the individual’s stated needs and goals for health care.40–42

There are obstacles to implementing an SCP. The IOM recommends that the patient’s “managing physician” be the plan’s author, but that specialty cannot be uniformly established. Specific cancer diagnoses and treatment needs dictate which physicians are involved in comprehensive cancer and survivorship care, and increasingly, these roles are complex and poorly coordinated.43 Thus, the provider responsible for creating the treatment summary or interviewing the patient will vary, and oversight of the implementation process will necessarily be fragmented. In addition, patients may deliberately avoid care; in the Vetcares sample, nearly half admitted to staying away from the medical center after treatment ceased because of being “tired of it all.” Others shunned post cancer treatment follow-up due to fears that tests might reveal bad news.

A VHA Template

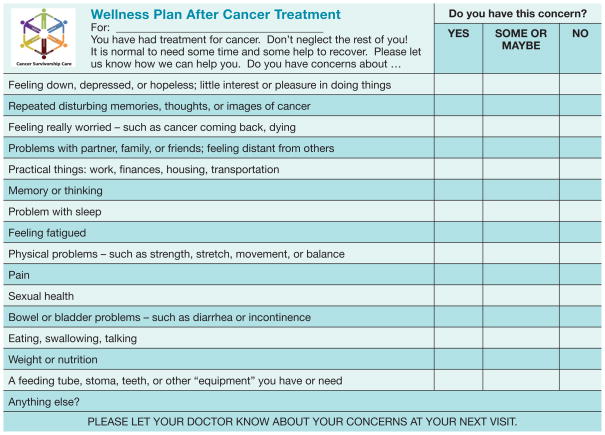

A working group within the VHA special interest group on cancer survivorship developed a CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System) template for an SCP that is based on the IOM recommendations. The group translated these recommendations into the relevant clinical data elements using 3 components: (1) a treatment summary; (2) a surveillance plan; and (3) a wellness plan (Figure). For those working within the VA system, the template is available on the VA intranet for download into the local CPRS template package. Local sites can then adapt the template as desired.

Figure. VHA Wellness Plan Template.

Source: https://vaww.visn11.portal.va.gov/sites/VERC/va-case/collabs/survivor_toolkit/SitePages/Home.aspx (Note: this is an internal VA website accessible to VA personnel only.

The Wellness Plan Component

A key part of this SCP that distinguishes it from others is the wellness plan. Importantly, this component asks the patient to report, to his primary care physician or other provider, specific concerns that may warrant referrals for rehabilitative care. In this way, the VHA SCP elicits patient participation and perspective to a greater extent than those plans that focus more narrowly on summarizing treatment. The items on the wellness plan were chosen based on the frequency with which they were identified among the veterans in the study sample as well as on a consensus of the VHA working group’s members.

Consumer feedback, as provided by 4 veterans who piloted the SCP, suggested that the plan should be completed approximately 3 months after cancer treatment. Because of variables in cancer treatment and in the organizational structure of VA facilities nationwide, flexibility in using and adapting these tools is inevitable and desirable. Since the majority of survivorship research focuses on women who are breast cancer survivors, while the data presented here are based on oral-digestive cancer survivors, additional work is needed to cross-validate the wellness plan content across cancer types as well as to determine effective methods for implementation that address both system and patient barriers to care.

CONCLUSION

Awareness of the need for cancer survivorship care is growing nationwide and within the VHA, and will become a required standard for CoC accreditation in 2015. With the VA’s leadership in both electronic medical records and integrated care, we are well poised to set an example of meaningful, patient-centered survivorship care.

Fast Facts….

There are now more than 13 million cancer survivors in the U.S.; 500,000 in the VHA1,2

Psychosocial distress and functional disability are common after cancer treatment. These problems often go untreated, increasing risk for ongoing disability

The survivorship care plan (SCP) is a mechanism to improve transition care by providing information, education, and referral, but traditional approaches have lacked the patient’s perspective

A wellness plan template has been developed to augment survivorship care planning in the VHA

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the veterans who have participated in these research studies and who allow us to contribute to their health care. We thank the members of the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vetcares) Research team and the VHA national special interest group on cancer survivorship, particularly the survivorship care plan subgroup.

Funding was provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, 5I01RX000104-02. This material is the result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities of the VA Medical Centers for each author. In addition, Dr. Naik receives resources and support from the Houston Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413) at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center.

Footnotes

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jennifer Moye, Staff psychologist at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, and is an associate professor of psychology in the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Ms. Maura Langdon, Cancer program administrator and acting administrative officer, Radiation Oncology, for the VA New York Harbor Cancer Program, Brooklyn, New York.

Ms. Janice M. Jones, Advance practice urology nurse at the Pittsburgh VA Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Dr. David Haggstrom, Core investigator in the VA HSR&D Center for Health Information and Communication at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, and an associate professor in the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

Dr. Aanand D. Naik, Geriatrician and health services investigator at the Houston Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (IQuESt) at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas, and is an associate professor of medicine and health policy at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed May 15, 2012];Estimated US Cancer Prevalence Counts: Who Are Our Cancer Survivors in the US? 2008 http://www.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/prevalence/index.html.

- 2.Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naik AD, Martin LA, Karel M, et al. Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vet-CaRes) BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehnert A, Koch U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moye J, Gosian J, Snow R, Naik A the Vet-CaRes Research Team. Emotional health following diagnosis and treatment of oral-digestive cancer in military veterans. Poster presented at: 119th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2011; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda K, Goodwin RD. Cancer and mental disorders in a national community sample: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(4):235–242. doi: 10.1159/000077742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating NL, Norredam M, Landrum MB, Huskamp HA, Meara E. Physical and mental health status of older long-term cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2145–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. A conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22(4):499–524. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DuHamel KN, Ostrof J, Ashman T, et al. Construct validity of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist in cancer survivors: analyses based on two samples. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(3):255–266. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at: 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; October 1993; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilgeman M, Moye J, Archambault E, et al. In the veteran’s voice: psychosocial needs after cancer treatment. Fed Pract. 2012;29(suppl 3):51S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):306–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moye J, Wachen JS, Mulligan EA, Doherty K, Naik AD. Assessing multidimensional worry in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):237–240. doi: 10.1002/pon.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deimling GT, Wagner LJ, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Kercher K, Kahana B. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(2):143–159. doi: 10.1002/pon.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Short PF, Vasey JJ, Belue R. Work disability associated with cancer survivorship and other chronic conditions. Psychooncology. 2008;17(1):91–97. doi: 10.1002/pon.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MK, Lee KM, Bae JM, et al. Employment status and work-related difficulties in stomach cancer survivors compared with the general population. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(4):708–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulligan E, Schwartzenburg M, Naik A, et al. Social relationships among military Veterans with oral-digestive cancers: risk and protective factors. Poster presented at: 120th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2012; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penedo FJ, Traeger L, Benedict C, et al. Perceived social support as a predictor of disease-specific quality of life in head-and-neck cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(3):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sultan S, Fisher DA, Voils CI, Kinney AY, Sandler RS, Provenzale D. Impact of functional support on health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson-Hanley C, Sherman ML, Riggs R, Agocha VB, Compas BE. Neuropsychological effects of treatments for adults with cancer: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(7):967–982. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703970019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK. Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(4):223–232. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed December 24, 2013];Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PRO-MIS) Web site. www.nihpromis.org.

- 25.Zebrack BJ, Yi J, Petersen L, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17(9):891–900. doi: 10.1002/pon.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman L, Gosian J, Walder A, Schwartzenburg M, Moye J, Naik A. The physical and psychological burden of oral-digestive cancer on veteran cancer survivors. Poster presented at: 8th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology; October 19–21, 2012; Omaha, NE. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deimling GT, Sterns S, Bowman KF, Kahana B. The health of older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(6):415–424. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200511000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moye J, June A, Martin LA, Gosian J, Herman L, Naik AD. Pain is prevalent and persisting in cancer survivors: Differential factors across age groups. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(2):190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta P, Haggstrom DA, Latini DM, Ballard EA, Moye J. Cancer survivorship care: summarizing the six tools for success. Fed Pract. 2011;28(suppl 6):43–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ananth H, Jones L, King M, Tookman A. The impact of cancer on sexual function: a controlled study. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):202–205. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm759oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Committee on Cancer Survivorship. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerlid E, Taft C. Health-related quality of life in long-term head and neck cancer survivors: a comparison with general population norms. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(2):149–156. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacon CG, Giovannucci E, Testa M, Glass TA, Kawachi I. The association of treatment-related symptoms with quality-of-life outcomes for localized prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;94(3):862–871. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsey SD, Berry K, Moinpour C, Giedzinska A, Andersen MR. Quality of life in long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(5):1228–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder CF, Earle CC, Herbert RJ, Neville BA, Blackford AL, Frick KD. Trends in follow-up and preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):254–259. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark EJ, Stovall EL, Leigh S, Siu AL, Austin DK, Rowland JH. Access, Advocacy, Action, and Accountability. Silver Spring, MD: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; 1996. National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knobf MT, Ferrucci LM, Cartmel B, et al. Needs assessment of cancer survivors in Connecticut. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting, Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Surgeons. [Accessed December 24, 2013];Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards. 2012 http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.html.

- 40.Smith TJ, Snyder C. Is it time for (survivorship care) plan B? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36):4740–4742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell MK, Tessaro I, Gellin M, et al. Adult cancer survivorship care: experiences from the LIVESTRONG centers of excellence network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):271–282. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gage EA, Pailler M, Zevon MA, et al. Structuring survivorship care: discipline-specific clinician perspectives. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):217–225. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naik AD, Singh H. Electronic health records to coordinate decision making for complex patients: what can we learn from wiki? Med Decis Making. 2010;30(6):722–731. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10385846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]