Abstract

Bats are likely natural hosts for a range of zoonotic viruses such as Marburg, Ebola, Rabies, as well as for various Corona- and Paramyxoviruses. In 2009/10, researchers discovered RNA of two novel influenza virus subtypes – H17N10 and H18N11 – in Central and South American fruit bats. The identification of bats as possible additional reservoir for influenza A viruses raises questions about the role of this mammalian taxon in influenza A virus ecology and possible public health relevance. As molecular testing can be limited by a short time window in which the virus is present, serological testing provides information about past infections and virus spread in populations after the virus has been cleared. This study aimed at screening available sera from 100 free-ranging, frugivorous bats (Eidolon helvum) sampled in 2009/10 in Ghana, for the presence of antibodies against the complete panel of influenza A haemagglutinin (HA) types ranging from H1 to H18 by means of a protein microarray platform. This technique enables simultaneous serological testing against multiple recombinant HA-types in 5μl of serum. Preliminary results indicate serological evidence against avian influenza subtype H9 in about 30% of the animals screened, with low-level cross-reactivity to phylogenetically closely related subtypes H8 and H12. To our knowledge, this is the first report of serological evidence of influenza A viruses other than H17 and H18 in bats. As avian influenza subtype H9 is associated with human infections, the implications of our findings from a public health context remain to be investigated.

Introduction

Bats are likely reservoirs for a range of zoonotic viruses, such as rabies and other lyssaviruses (family Rhabdoviridae), Ebola- and Marburg viruses (Filoviridae), Hendra- and Nipah viruses (Paramyxoviridae), as well as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus (Coronaviridae) [1]. In 2009/10, influenza A expanded the list of viral pathogens found in bats, when RNA of two novel influenza A virus (IAV) subtypes (Orthomyxoviridae), H17N10 and H18N11, was discovered in frugivorous bats from Guatemala and Peru, respectively [2,3]. Until then, sixteen hemagglutinin (HA)- and nine neuraminidase (NA) types, two surface proteins utilized to classify IAV into subtypes, had been previously described. Water- and shore birds have been known to be the only relevant reservoir hosts for IAV [4]. Several IAV subtypes originating from birds have established stable lineages in birds, pigs and humans. Other avian (e.g., H5N1, H6N2, H7N9, H10N8) and swine influenza virus subtypes (e.g., most recently H3N2v) occasionally cause human infection, resulting in mild- to severe disease and occasional death [5].

Although the two newly discovered subtypes were recently found to have no zoonotic potential [6], the aim of this study was to investigate the role of bats as potential mammalian reservoirs for possibly zoonotic influenza A viruses, by screening for serological evidence against all currently known influenza virus HA-types in frugivorous bats from Ghana.

Methods

Ethics statement

As described previously [7], all animals used in this study were captured and sampled with permission from the Wildlife Division, Forestry Commission, Accra, Ghana. Geographic coordinates of the sampling site in Kumasi/Ghana were N06°42´02.0´´ W001°37´29.9´´. Capturing was conducted under the auspices of Ghana authorities. Following anesthesia using a Ketamine/Xylazine mixture, skilled staff exsanguinated all bats (permit no. CHRPE49/09; A04957). Samples were exported under a state contract between the Republic of Ghana and the Federal Republic of Germany. An additional export permission was obtained from the Veterinary Services of the Ghana Ministry of Food and Agriculture (permit no. CHRPE49/09; A04957). Materials of all sacrificed animals were used for various studies [8–11].

Sample Analysis

Serum samples (n = 100) from straw-colored fruit bats (Eidolon helvum, Pteropodidae) were collected in 2009 (n = 81) and 2010 (n = 19) in Kumasi Zoo in Ghana. Although sampling was performed at Kumasi Zoo, all bats included in this study belonged to a wild, migratory colony roosting in trees on site at the time of sample collection.

For serological testing, we used a modification of the protein microarray (PA) technique as previously described by Koopmans et al. [12] and Freidl et al. [13]. 31 recombinant proteins of influenza A viruses [globular head domains (HA1)] were printed in duplicates onto nitrocellulose Film-slides (16 pad, ONCYTE AVID, Grace Bio-Labs, Bend, Oregon, USA). Selected proteins comprised various strains of all presently known influenza A virus HA-types. Reactivity and optimal working concentration of the proteins were determined by means of checkerboard titrations using specific rabbit antisera homologous to the antigens used (Table 1). Printed slides were stored in a desiccation chamber until further use.

Table 1. Recombinant HA1-proteins included in the protein microarray.

| # | Code | Subtype | Strain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H1.18 | H1N1 | A/South Carolina/1/18 |

| 2 | H1.77 | H1N1 | A/USSR/92/1977 |

| 3 | H1.07 | H1N1 | A/Brisbane/59/2007 |

| 4 | H1.09 | H1N1 | A/California/6/2009 |

| 5 | H2.05 | H2N2 | A/Canada/720/05 |

| 6 | H3.68 | H3N2 | A/Aichi/2/1968(H3N2) |

| 7 | H3.10 | H3N2v | A/Minnesota/09/2010 |

| 8 | H3.07 | H3N2 | A/Brisbane/10/2007 |

| 9 | H4.02 | H4N6 | A/mallard/Ohio/657/2002 |

| 10 | H5.97 | H5N1 | A/Hong Kong/156/97 (HP, clade 0) a |

| 11 | H5.02 | H5N8 | A/duck/NY/191255-59/2002, LP b |

| 12 | H5.10 | H5N1 | A/Hubei/1/2010 (HP, clade 2.3.2.1) a |

| 13 | H5.06 | H5N1 | A/Turkey/15/2006 (HP, clade 2.2) a |

| 14 | H5.07 | H5N1 | A/Cambodia/R0405050/2007 (HP, clade 1) a |

| 15 | H5.05 | H5N1 | A/Anhui/1/2005 (HP, clade 2.3.4) a |

| 16 | H6.07 | H6N1 | A/northern shoveler/California/HKWF115/2007 |

| 17 | H7.03 | H7N7 | A/Chicken/Netherlands/1/03 (HP) a |

| 18 | H7.13 | H7N9 | A/chicken/Anhui/1/2013 (LP) b |

| 19 | H7.12 | H7N3 | A/chicken/Jalisco/CPA1/2012 (HP) |

| 20 | H8.79 | H8N4 | A/pintail duck/Alberta/114/1979 |

| 21 | H9.97 | H9N2 | A/chicken/Hong Kong/G9/97 (G9 lineage) |

| 22 | H9.09 | H9N2 | A/Hong-Kong/33982/2009 (G1 lineage) |

| 23 | H10.07 | H10N7 | A/blue-winged teal/Louisiana/Sg00073/07 |

| 24 | H11.02 | H11N2 | A/duck/Yangzhou/906/2002 |

| 25 | H12.91 | H12N5 | A/green-winged teal/ALB/199/1991 |

| 26 | H13.00 | H13N8 | A/black-headed gull/Netherlands/1/00 |

| 27 | H14.82 | H14N5 | A/mallard/Astrakhan/263/1982new |

| 28 | H15.83 | H15N8 | A/duck/AUS/341/1983 |

| 29 | H16.99 | H16N3 | A/black-headed gull/Sweden/5/99 |

| 30 | H17.09 | H17N10 | A/little yellow shouldered bat/ Guatemala/153/2009 |

| 31 | H18.14 | H18N11 | A/flat-faced bat/Peru/033/2010 |

Proteins were obtained from Immune Technology Corp. (NY, USA) or Sino Biological Inc. (Beijing, China).

ahighly pathogenic

blow pathogenic

Prior to analysis, we inactivated all bat sera in a water bath at 56°C for one hour. Four-fold sample dilutions were prepared in Blotto Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, MA, USA) containing 0.1% Surfactant-Amps (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). We used five microliters of serum for a starting concentration of 1:40.

Serum dilutions were incubated for one hour in a moist, dark box at 37°C. Antibody binding was detected using an unconjugated goat-anti-bat whole immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA) at a dilution of 1:800, in combination with a Fc-fragment specific AlexaFluor647-labelled rabbit-anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc, West Grove, PA, USA) at 1:1100. Both conjugates were titrated to determine the optimal working concentration prior to sample analysis. Each incubation period followed three washing steps using wash buffer (Maine Manufacturing, Maine, USA).

Fluorescent signals were measured with a Powerscanner (Tecan Group Ltd, Männedorf, Switzerland) and converted into titers as described before [12,13]. The detection capacity of the PA spanned a titer range from 40 to 2560. Samples showing no antibody reactivity were regarded as negative and were assigned a titer of 20 (half of the starting dilution). As we were unable to formally calculate a cut-off based on confirmed influenza A-positive and negative bat sera due to unavailability of such materials, an arbitrary cut-off of 40 was chosen, similarly to previous work [12]. Hence, samples displaying a dilution curve resulting in a titer of ≥40 were interpreted as positive. Comparisons of seropositivity between sexes, age groups, sampling seasons and-years, respectively, were performed using Chi2- or Fisher’s exact test in RStudio (Version 0.98.507, Boston, MA, USA) with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

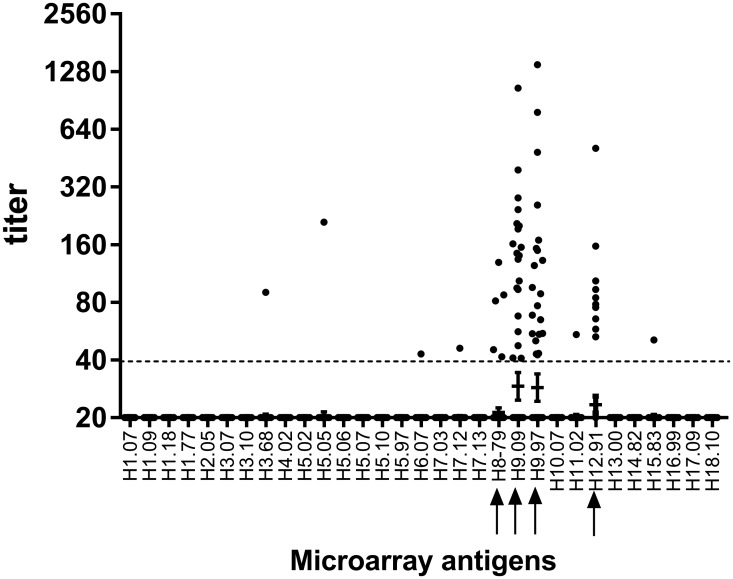

Of the 100 bats tested, 67 (67%) were negative against all antigens (Fig 1), whereas 33 bats showed titers against one or more antigens [2009: 26 (32%); 2010: 7 (37%)]. Four antigens showed slightly elevated geometric mean titers (GMT): H8.79: 21, H9.97: 29, H9.09: 29, H12.91: 23, whereas the GMT against the remaining antigens was 20 (Fig 1). Thirty bats (30%) showed antibody titers higher than 40 against at least one H9-antigen included on the PA. Thereof, 21 (21%) bats were positive for H9.97 (range: 43–1388) and 20 (20%) for H9.09 (range: 41–1048), respectively. Eleven animals showed antibody reactivity against both H9-antigens (11%), whereas ten individuals (10%) selectively reacted with H9.97, and nine (9%) solely with H9.09. Of the H9-positive bats, 24 were sampled in 2009 (29.6%) and 6 in 2010 (31.6%), respectively.

Fig 1. Titers of individual Ghanaian bats plotted against all recombinant proteins included on the microarray.

Horizontal bars represent geometric mean titers per antigen including a 95% confidence interval. Sera below fluorescence values of 31.268 (half of the fluorescence spectrum) were regarded as negative and were assigned a titer of 20 (half of the starting dilution of 1:40). Sera above 40 (dashed line) were regarded as positive. Arrows indicate antigens grouping within the same phylogenetic cluster.

Ten of the samples from H9 positive bats also bound to the H12.91 protein (range: 53–509), and four in addition bound to H8.79 protein (range: 42–129). Serum from one of these four bats had additional reactivity to H11.02 antigen. Similarly, two other H9.97-positive individuals, reacted against H7.12 (titer: 46) and H15.83 (51), or with H6.07 (43). Unique reactivity to single proteins was observed for H3 (n = 1), H5 (n = 1) and H8 (n = 1, titer: 42). We found no significant differences in seropositivity between sexes, age groups, sampling season and —year, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Serological findings versus sex, age group, sampling year and—season.

| serology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative | positive | Row total | p-value | ||

| sex a | male | 51 | 22 | 73 | 0.4463 |

| female | 16 | 11 | 27 | ||

| age group b | adult | 54 | 31 | 85 | 0.134 |

| juvenile | 13 | 2 | 15 | ||

| year a | 2009 | 55 | 26 | 81 | 0.9008 |

| 2010 | 12 | 7 | 19 | ||

| season b , c | dry | 6 | 4 | 10 | 0.7259 |

| rainy | 61 | 29 | 90 | ||

| Column total | 67 | 33 | 100 | ||

Comparisons showed no significant differences. Counts also reflect percentages (n = 100).

aPearson’s Chi2-test with continuity correction

bFisher’s exact test

cdry: December to February, rainy: March to July and September to November.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we report on serological evidence of influenza A viruses in straw-colored fruit bats from Ghana. We found no reactivity against H17 antigens such as recorded in bats from Guatemala (38% [2] or H18 antigens like in bats from Peru (27% [3]. However, we studied a not closely related bat species from a different continent, and found about 30% antibody detection rate against HA-type H9. Sonntag et al. [14] and Fereidouni et al. [15] screened Central European bats for genomic traces of influenza virus using generic RT-PCR assays but found no such evidence. For the Central and South American bats influenza virus RNA was detected in a low percentage (0.9%) of the Guatemalan (3/316) and Peruvian (1/110) bats by pan-influenza conventional RT-PCR [2,3]. However, molecular detection is limited by a short duration of virus excretion making it impossible to exclude virus presence on population level. Serological techniques can shed light on the infection history even after the virus has been cleared by the immune system. Still, serological tests are limited in their specificity due to the existence of cross reactive antibodies [16]. As with every attempt to study infection in novel host systems, our techniques are not finally optimized for use with bats due to limited availability of reagents (including confirmed influenza A positive- and negative bat sera) [17,18]. Moreover, there was insufficient sample material for additional analyses such as microneutralization- or hemagglutination inhibition assays due to utilization of materials in prior studies [8–11]. Our results are preliminary in this regard, leaving the possibility that antibodies in bats may not be directed against typical avian-origin H9 HA lineages, but outlier viruses yet to be discovered.

Nevertheless, several of the bat sera showing H9-reactivity also reacted with antigens H8 and H12. This supports the credibility of our findings as there is clear phylogenetic relatedness of these particular subtypes[19]. Similar intra-clade reactivity was previously observed in chickens naturally infected with subtype H9N2 [13]. No significant association in seropositivity between sex, age groups, sampling year and season, respectively, could be found. However, as sample size was small we cannot rule out that potentially significant associations might have been missed.

Influenza A viruses of HA-type H9 have a wide geographical distribution in birds and are recognized as possible candidates to cause a future pandemic [20]. In addition, this subtype is associated with human infection causing mostly mild symptoms, which likely leads to an underestimation of cases [5]. Limited surveillance in birds allow unnoticed reassortment events between circulating avian or potentially human influenza virus strains, resulting in variants with yet unknown zoonotic potential [21]. Given the relatively high seroprevalence found in bats in both sampling years and the clinically healthy status at the time of sample collection, we cautiously suggest that bats—as for other emerging viruses [22]—might constitute asymptomatic mammalian carriers of influenza A viruses. In summary, we present serological evidence of influenza A viruses in Old World fruit bats that have been shown to be biologically relevant reservoirs of pathogenic viruses such as Henipaviruses, Coronaviruses, Lyssaviruses and Filoviruses. It is conceivable that there might be a link between serological evidence of influenza A virus in bats and migratory birds, as their flyways overlap with the geographic distribution of E. helvum [23,24]. However, in the absence of molecular data this hypothesis remains speculative. As E. helvum are widely consumed as bush meat in West Africa [25], the implications of the findings from a public health perspective remain to be investigated. Serological studies in humans consuming bats (including suitable control groups) would be useful to shed light on possible spillover events.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by the European Commission's FP7 program under the umbrella of the Antigone project - ANTIcipating the Global onset of Novel Epidemics (project number 278976, http://antigonefp7.eu/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hayman DTS, Bowen RA, Cryan PM, McCracken GF, O’Shea TJ, Peel AJ, et al. Ecology of Zoonotic Infectious Diseases in Bats: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Zoonoses Public Health 2013;60:2–21. 10.1111/zph.12000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tong S, Li Y, Rivailler P, Conrardy C, Castillo DAA, Chen L-M, et al. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012;109:4269–74. 10.1073/pnas.1116200109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tong S, Zhu X, Li Y, Shi M, Zhang J, Bourgeois M, et al. New World Bats Harbor Diverse Influenza A Viruses. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003657 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fouchier RAM, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D, et al. Characterization of a Novel Influenza A Virus Hemagglutinin Subtype (H16) Obtained from Black-Headed Gulls. J Virol 2005;79:2814–22. 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2814-2822.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freidl GS, Meijer A, de Bruin E, de Nardi M, Munoz O, Capua I, et al. Influenza at the animal-human interface: a review of the literature for virological evidence of human infection with swine or avian influenza viruses other than A(H5N1). Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull 2014;19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou B, Ma J, Liu Q, Bawa B, Wang W, Shabman RS, et al. Characterization of uncultivable bat influenza virus using a replicative synthetic virus. PLoS Pathog 2014;10:e1004420 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eckerle I, Ehlen L, Kallies R, Wollny R, Corman VM, Cottontail VM, et al. Bat Airway Epithelial Cells: A Novel Tool for the Study of Zoonotic Viruses. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e84679 10.1371/journal.pone.0084679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drexler JF, Corman VM, Müller MA, Maganga GD, Vallo P, Binger T, et al. Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun 2012;3:796 10.1038/ncomms1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drexler JF, Geipel A, König A, Corman VM, van Riel D, Leijten LM, et al. Bats carry pathogenic hepadnaviruses antigenically related to hepatitis B virus and capable of infecting human hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:16151–6. 10.1073/pnas.1308049110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drexler JF, Corman VM, Müller MA, Lukashev AN, Gmyl A, Coutard B, et al. Evidence for novel hepaciviruses in rodents. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003438 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Binger T, Annan A, Drexler JF, Müller MA, Kallies R, Adankwah E, et al. A Novel Rhabdovirus Isolated from the Straw-Colored Fruit Bat Eidolon helvum, with Signs of Antibodies in Swine and Humans. J Virol 2015;89:4588–97. 10.1128/JVI.02932-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koopmans M, de Bruin E, Godeke G-J, Friesema I, van Gageldonk R, Schipper M, et al. Profiling of humoral immune responses to influenza viruses by using protein microarray. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18:797–807. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freidl GS, de Bruin E, van Beek J, Reimerink J, de Wit S, Koch G, et al. Getting more out of less—a quantitative serological screening tool for simultaneous detection of multiple influenza a hemagglutinin-types in chickens. PloS One 2014;9:e108043 10.1371/journal.pone.0108043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sonntag M, Muhldorfer K, Speck S, Wibbelt G, Kurth A. New Adenovirus in Bats, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:2052–5. 10.3201/eid1512.090646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fereidouni S, Kwasnitschka L, Balkema Buschmann A, Müller T, Freuling C, Schatz J, et al. No Virological Evidence for an Influenza A—like Virus in European Bats. Zoonoses Public Health 2014. 10.1111/zph.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katz JM, Hancock K, Xu X. Serologic assays for influenza surveillance, diagnosis and vaccine evaluation. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2011;9:669–83. 10.1586/eri.11.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilbert AT, Fooks AR, Hayman DTS, Horton DL, Müller T, Plowright R, et al. Deciphering serology to understand the ecology of infectious diseases in wildlife. EcoHealth 2013;10:298–313. 10.1007/s10393-013-0856-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peel AJ, McKinley TJ, Baker KS, Barr JA, Crameri G, Hayman DTS, et al. Use of cross-reactive serological assays for detecting novel pathogens in wildlife: assessing an appropriate cutoff for henipavirus assays in African bats. J Virol Methods 2013;193:295–303. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. WHO. A revision of the system of nomenclature for influenza viruses: a WHO memorandum. Bull World Health Organ 1980;58:585–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fusaro A, Monne I, Salviato A, Valastro V, Schivo A, Amarin NM, et al. Phylogeography and evolutionary history of reassortant H9N2 viruses with potential human health implications. J Virol 2011:JVI.00219–11. 10.1128/JVI.00219-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qi W, Shi W, Li W, Huang L, Li H, Wu Y, et al. Continuous reassortments with local chicken H9N2 virus underlie the human-infecting influenza A (H7N9) virus in the new influenza season, Guangdong, China. Protein Cell 2014;5:878–82. 10.1007/s13238-014-0084-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Shea TJ, Cryan PM, Cunningham AA, Fooks AR, Hayman DTS, Luis AD, et al. Bat Flight and Zoonotic Viruses. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:741–5. 10.3201/eid2005.130539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olsen B, Munster VJ, Wallensten A, Waldenstrom J, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Global patterns of influenza a virus in wild birds. Science 2006;312:384–8. doi:Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ossa G, Kramer-Schadt S, Peel AJ, Scharf AK, Voigt CC. The Movement Ecology of the Straw-Colored Fruit Bat, Eidolon helvum, in Sub-Saharan Africa Assessed by Stable Isotope Ratios. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e45729 10.1371/journal.pone.0045729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamins AO, Restif O, Ntiamoa-Baidu Y, Suu-Ire R, Hayman DTS, Cunningham AA, et al. Uncovering the fruit bat bushmeat commodity chain and the true extent of fruit bat hunting in Ghana, West Africa. Biol Conserv 2011;144:3000–8. 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.