Abstract

Background:

Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with lower quality of life, more fatigue, and reduced adherence to disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Objectives:

The objectives of this review are to estimate the incidence and prevalence of selected comorbid psychiatric disorders in MS and evaluate the quality of included studies.

Methods:

We searched the PubMed, PsychInfo, SCOPUS, and Web of Knowledge databases and reference lists of retrieved articles. Abstracts were screened for relevance by two independent reviewers, followed by full-text review. Data were abstracted by one reviewer, and verified by a second reviewer. Study quality was evaluated using a standardized tool. For population-based studies we assessed heterogeneity quantitatively using the I2 statistic, and conducted meta-analyses.

Results:

We included 118 studies in this review. Among population-based studies, the prevalence of anxiety was 21.9% (95% CI: 8.76%–35.0%), while it was 14.8% for alcohol abuse, 5.83% for bipolar disorder, 23.7% (95% CI: 17.4%–30.0%) for depression, 2.5% for substance abuse, and 4.3% (95% CI: 0%–10.3%) for psychosis.

Conclusion:

This review confirms that psychiatric comorbidity, particularly depression and anxiety, is common in MS. However, the incidence of psychiatric comorbidity remains understudied. Future comparisons across studies would be enhanced by developing a consistent approach to measuring psychiatric comorbidity, and reporting of age-, sex-, and ethnicity-specific estimates.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, comorbidity, systematic review, incidence, prevalence, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, psychosis

Introduction

Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with lower quality of life, greater levels of fatigue, and reduced adherence to disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis (MS).1,2 Therefore a clear understanding of the risk of developing these conditions (their incidence), and their prevalence in established MS populations is needed. Depression, and to a lesser extent, anxiety are recognized to affect the MS population more often than the general population.3 However, many studies evaluating the prevalence of these conditions have been clinic-based, creating potential selection biases. Prevalence estimates for bipolar disorder and psychosis have been variable,4,5 and the literature is inconsistent with respect to the relative frequency of these conditions in the MS population versus the general population.

In this systematic review we aimed to estimate the incidence and prevalence of selected psychiatric comorbidity in MS, as well as to evaluate the quality of all studies reviewed. We expect that this work will improve our understanding of the gaps in the literature regarding psychiatric comorbidity and assist the design of future studies evaluating the impact of psychiatric comorbidity in MS.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of a larger review of the global incidence and prevalence of comorbidity in MS.6 Herein we describe the findings for comorbid psychiatric disorders including anxiety, alcohol abuse, bipolar disorder, depression, drug abuse, personality disorders, and psychosis.

Briefly, the search strategy for psychiatric disorders examined the published literature and conference proceedings using PubMed, PsychInfo, SCOPUS, and Web of Knowledge for all years available through November 18, 2013 (Supplemental Appendix I).6 We manually reviewed the reference lists of studies identified from the electronic searches. After identifying unique citations, two reviewers (RAM, NR) independently assessed abstract relevance. If either reviewer selected the abstract it underwent full-text review to determine if it met study inclusion criteria. Specifically, the study had to (i) include an MS population, (ii) report original data, (iii) specify the comorbidity or comorbidities of interest, (iv) report the incidence or prevalence of the comorbidity, and (v) be published in English. After the two reviewers independently completed the full-text review, disagreements were resolved by consensus.

One reviewer abstracted data using a standardized data collection form and the findings were verified by the second reviewer. The data collection form captured general study characteristics as well as incidence and prevalence estimates (see Marrie et al.6). Each study was critically appraised using a standardized assessment tool developed for a systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of MS.7 Quality scores were awarded based on yes or no responses to nine questions.6 This process supported a qualitative assessment of study heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis

Using the I2 test we quantified study heterogeneity among population-based studies with the aim of estimating incidence or prevalence. Using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, we conducted random-effects meta-analyses.8 For studies in which zero events were recorded we employed a continuity correction of 0.5.9

Results

Psychiatric disorders

Search

The search identified 4047 unique citations (Supplemental Figure 1). After abstract screening and hand searching of reference lists, 317 articles met the criteria for full-text review, of which we excluded 199. A total of 118 studies were the subject of this review (Supplemental Tables 1-15).3,5,10–130

Study characteristics

The studies were conducted from 1953 to 2012, and most were conducted in Europe (58, 49.1%), followed by North America (43, 36.4%), Asia (10, 8.5%), Australia (four, 3.4%) and South America (one, 0.85%). Psychiatric disorders were identified predominantly using validated or unvalidated questionnaires (80, 67.8%), diagnostic interviews (16, 13.5%), administrative data (14, 11.9%), and medical records or clinical databases (four, 3.4%). Some studies used more than one type of data source. Common study limitations included the lack of a population-based design, failure to describe non-responders in survey-based studies, the failure to use validated criteria to assess the diagnosis of MS, and failure to report confidence intervals (CIs). Quality scores varied widely from one of nine to eight of eight overall, and from four of eight to eight of eight among population-based studies ((Supplemental Table 1, “Overview” manuscript).6 The rest of the text will focus largely on findings from the population-based studies.

Anxiety

None of the studies reported the incidence of anxiety disorders, while 41 reported the prevalence of diagnosed anxiety disorders (13, 31.7%), symptoms of anxiety (26, 63.4%), or both (two) (Supplemental Table 2).3,14,16,18,19,24,26,27,30,32,34,37–39,43,50,56–80 Diagnosed anxiety disorders or previously undiagnosed anxiety disorders meeting diagnostic criteria were captured using structured diagnostic interviews, medical records review or self-reported diagnoses. Symptoms of anxiety were captured using validated instruments including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Beck Anxiety Inventory. Of these the most commonly used instrument was the HADS.

Considering all studies, the prevalence of diagnosed anxiety ranged from 1.24% to 36% (Supplemental Table 2). The prevalence of a self-reported diagnosis of anxiety at the time of MS symptom onset was 2.72%, while it increased to 6.23% at the time of MS diagnosis.38 One study evaluated the prevalence of health anxiety as a construct distinct from generalized anxiety, reporting a prevalence of 26.4%.67

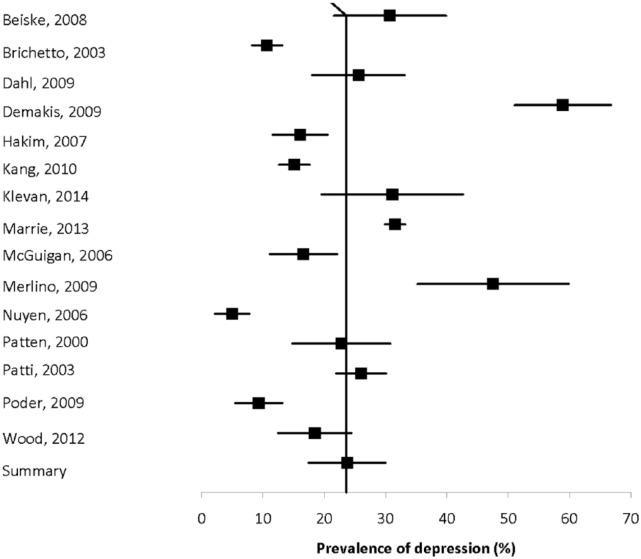

Eight population-based studies with quality scores ranging from six of eight to eight of eight reported the prevalence of anxiety (generalized or unspecified) to range from 1.2% to 44.6% (Figure 1).3,16,56,59,65,74,80 Heterogeneity among these studies was substantial (I2 = 99.2), and the summary estimate was 21.9% (95% CI: 8.76%–35.0%). Recognizing that differences in study design, including the method of assessing anxiety, likely contributed to the high degree of heterogeneity, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we restricted the analysis to those using questionnaires to assess symptoms of anxiety. Among these five studies heterogeneity remained substantial (I2 = 88.6), and the summary estimate was 25.5% (95% CI: 16.7%–34.3%). We then further excluded the only one that did not use the HADS, but the observed heterogeneity persisted (I2 = 91.3) and the impact on the summary estimate was minimal (27.2%; 95% CI: 16.0%–38.4%). When we considered the three population-based studies that relied on diagnoses captured in administrative data, electronic medical records, or other medical records, heterogeneity remained substantial (I2 = 99.8) and the summary estimate was lower (15.4%; 95% CI: 0%–39.0%).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the prevalence of anxiety in multiple sclerosis in population-based studies.

Some studies evaluated subpopulations, including the pediatric MS population and individuals in nursing homes. Two studies reported the prevalence of anxiety in a pediatric MS population.26,79 In the Canadian study the prevalence was 31.0% by patient report, and 22.6% by parental report. In the Italian study the prevalence of panic disorders was 3.57%.26 In one American study the prevalence of an anxiety disorder in nursing home residents with MS was 9.32%.16 No other studies evaluated individuals with MS who did not live in the community.

Eight studies compared the prevalence of anxiety disorders or symptoms of anxiety in the MS population and a comparator population (Supplemental Table 2).3,24,38,56,58–60,79 Six of these studies found a higher prevalence of anxiety in the MS population, for both men and women. The sole study comparing specific anxiety disorders found that any anxiety disorder was more statistically significantly common in the general population, but obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, simple phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia were not, possibly because of the small sample size (n = 50 per group).24

Alcohol abuse

None of the studies reported the incidence of alcohol abuse, while eight reported the prevalence of alcohol abuse, misuse or dependence (Supplemental Table 3).18,24,74,83–87 However, the definitions used for these states varied, at least in part, because of the differing methods used in these studies, including using screening tools to predict individuals at high risk of these conditions (four, 50%), a structured diagnostic clinical interview (reference standard (two, 25%)), and administrative data (two, 25%). Even the screening tools used varied from one study to another, and included the Patient Health Questionnaire-4, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C), and the CAGE questionnaire. The prevalence of definite or probable alcohol abuse or dependence ranged from 3.96% to 18.2%. Only one study was population-based, capturing inpatient and outpatient care. This Taiwanese study reported the prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence to be 14.8%.86 Only one study reported sex-specific estimates, and none reported race-/ethnicity-specific estimates.

Only three studies compared the prevalence of alcohol misuse in the MS population to a comparator population; they consistently reported a higher prevalence in the MS population (Supplemental Table 4).24,84,86

Bipolar disorder

None of the studies reported the incidence of bipolar disorder, while 12 studies reported the lifetime prevalence to range from 0% to 16.2% (Supplemental Table 5).3,15–17,21,24,26,30,32,38,81,82 Some studies distinguished between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders, but this was not universal. Only one study was truly population based, and estimated the prevalence of bipolar disorder using administrative data to be 5.83%.3

One questionnaire-based study reported the prevalence of bipolar disorder at MS onset to be 0.50% and at MS diagnosis to be 0.98%.39 Of the 12 studies, one Italian study reported the prevalence of bipolar disorder in the pediatric MS population to be 3.57%.26

One study reported that the incidence of bipolar disorder was two-fold higher in the MS population during the four-year period after diagnosis as compared to the general population but did not report the absolute incidence in either the MS or comparator population.81 All seven studies comparing the prevalence of bipolar disorder in the MS population to a comparator population found that bipolar disorder was more common in the MS population (Supplemental Table 6).3,15,17,21,24,38,82 Only one of these studies was population-based, reporting a 1.7-fold higher prevalence of bipolar disorder in the MS population than in age-, sex-, and regionally matched controls.3

Depression

Two studies reported the incidence of depression (Supplemental Table 7),45,52 while 71 reported the prevalence (Supplemental Tables 8 and 9).3,10–38,41–59,63–67,70–80,93–130 The incidence of depression ranged from 4.0% in one year to 34.7% over a five-year period.45,52 The approaches used differed in the two studies. One study used a scale and the other administrative data, thus the findings are difficult to compare. Studies evaluating the prevalence of depression also varied in the methods used to identify depression, with some using formal diagnostic interviews, others using diagnoses abstracted from administrative databases or medical records, and still others using questionnaires (scales) aimed at detecting possible depression (Supplemental Table 9).

Among the studies using diagnostic interviews, some used the Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (SCID), while others used the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), or unstructured clinical interviews. Based on diagnoses conferred by interview or obtained from data sources other than questionnaires, the prevalence of depression ranged from 3.80% to 68.4% (Supplemental Table 8). Many of these studies focused on lifetime depression rather than current depression, but the distinction was not always explicit. Studies using diagnostic interviews noted that some individuals with MS met the diagnostic criteria for depression but had not been formally diagnosed.41

Among studies using validated questionnaires aiming at detecting possible depression (Supplemental Table 9),20,28,41,45,50,56–59,63–67,70–80,93–130 the instruments used also varied widely including the Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the HADS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Zung’s Self Rating Depression Scale, as well as pediatric instruments and translated versions of these instruments. Of these instruments the most commonly used were the Beck Depression Inventory, followed by the HADS and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. The performance of some of these scales has been evaluated in the MS population. Although performance has generally been adequate, false positives are a potential concern in these studies. Based on the use of questionnaires, the prevalence of depression ranged from 6.94% to 70.1% (Supplemental Table 9).

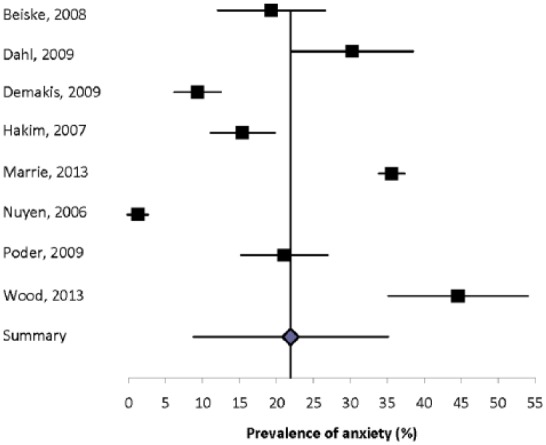

Fifteen population-based studies with quality scores ranging from four of eight to eight of eight to eight of nine evaluated the prevalence of depression using a mixture of methods, and reported estimates ranging from 4.98% to 58.9% (Figure 2).3,10,16,33,41,43,47,56,59,65,70,74,80,113,120 Heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 97.3), and the summary estimate was 23.7% (95% CI: 17.4%–30.0%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of depression in multiple sclerosis in population-based studies.

Ten studies compared the prevalence of depression diagnoses conferred by interview or obtained from data sources other than depression scales in the MS population and comparator populations (Supplemental Table 10).3,15,17,21,24,33,38,46,52,55 All found that depression was more prevalent in the MS population. Seven studies compared the prevalence of depression in the MS population and a comparator population based on the use of validated scales (Supplemental Table 11). All found that depression was more prevalent in the MS population, although one study in the pediatric MS population found this difference based only on parental report.

Drug abuse

None of the studies reported the incidence of drug abuse while three studies reported the prevalence of drug abuse, again using variable definitions (Supplemental Table 12).18,43,83 Two studies reported the prevalence of drug abuse to range from 2.5% to 7.4%.43,83 The lower of the two estimates was from a population-based study in the Netherlands.

Personality disorders

In one study of 651 patients, the prevalence of personality disorders in an Israeli clinic population was 2.6% (Supplemental Table 13).27 The authors did not classify the personality disorders by cluster.

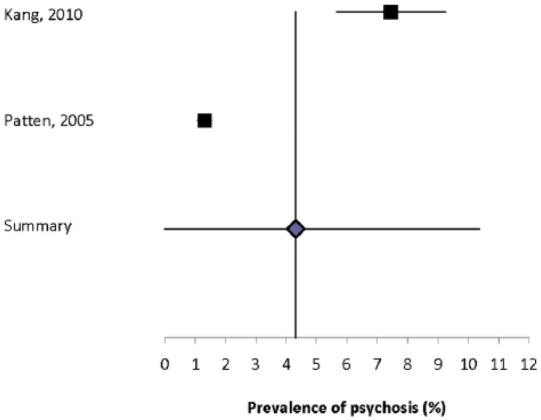

Psychosis

None of the studies reported the absolute incidence of psychosis. Ten studies reported the prevalence of psychosis,3,5,16,17,27,30,32,33,38,43 but four of these studies were restricted to schizophrenia3,30,32,38 and one was restricted to brief psychotic disorders (Supplemental Table 14).17 The prevalence of psychosis ranged from 0.41% to 7.46%, while the prevalence of schizophrenia ranged from 0% to 7.4%. The estimated prevalence of psychosis was markedly higher in the population-based study from Taiwan that used administrative data, as compared to other estimates in North America or Europe regardless of the methods used. The heterogeneity of the two population-based estimates for psychosis5,33 was substantial (I2 = 97.8) and the summary prevalence estimate was 4.3% (95% CI: 0%–10.3%) (Figure 3). The sole population-based estimate for schizophrenia was 0.93%.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence of depression in multiple sclerosis in population-based studies.

One study reported the prevalence of schizophrenia to be 0.06% at MS symptom onset, and to be 0.08% at MS diagnosis.39

One study reported that the incidence of psychosis did not differ in the MS population and the general population but did not report the absolute incidence of disease in either the MS or comparator population (Supplemental Table 15).81 Five studies compared the prevalence of psychosis or schizophrenia in the MS population to another population.3,5,17,33,38 All three studies that used concurrent controls reported that the prevalence of psychosis was higher in the MS population than in the comparator population.5,17,33 The sole study that evaluated schizophrenia using concurrent controls did not identify a difference in the prevalence of schizophrenia between the populations.3

Discussion

Psychiatric comorbidity has long been recognized as a concern in the MS population. This comprehensive systematic review confirms that psychiatric comorbidity is common in the MS population, and that this is particularly true for depression and anxiety, each of which affect more than 20% of the population. We identified nearly twice as many studies focused on depression as on anxiety, and far fewer studies devoted to other comorbidities such as bipolar disorder or alcohol abuse, despite their potential clinical importance. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity is high even at the time of MS diagnosis, and rises over the course of the disease. Further, depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder occur substantially more often in the MS population than in the general population even in studies accounting to some degree for socioeconomic status (largely by considering education). Findings for psychosis are inconsistent and require further study.

Global variation in the burden of depression and anxiety is recognized in the general population,131,132 but differences in study design prevented us from comparing findings across regions in the present review. Studies were largely conducted in Central or Western Europe or select regions of North America. Most world regions are understudied and warrant future attention.

Study designs were heterogeneous with respect to data sources, populations, and definitions of psychiatric comorbidity. Even among population-based studies heterogeneity remained high. This was particularly striking for depression, which was variously identified using diagnostic interviews, medical records review, administrative databases, and questionnaires. More than nine different questionnaires were used. To improve comparability prevalence estimates of depression or other psychiatric comorbidities across populations, future studies should use a consistent approach. In particular, comparisons of the psychometric properties of questionnaires used in the MS population would be useful, with a view to selecting one preferred instrument. We also noted that few studies reported age, sex or ethnicity-specific estimates. None of the studies standardized estimates to a common population, again limiting comparability of findings across studies.

The association of psychiatric comorbidity and MS may reflect several factors. First, in the general population, bidirectional relationships exist among depression, anxiety, and immune function.133 Depression, for example, may occur in response to immunological and inflammatory changes.134 Second, structural brain abnormalities as measured by brain atrophy and brain lesions are associated with depression in MS.135 In some patients psychosis has been attributed to brain lesions in the temporal lobe.136 Third, depression or anxiety may constitute a general response to chronic illness. Fourth, disease-modifying and symptomatic therapies used to manage MS may cause depression or anxiety. For example, corticosteroids may cause transient depression, mania or psychosis;137,138 while the pivotal trials of interferon-beta for MS raised concern about this therapy causing depression.135 Finally, psychosocial risk factors also play a role in psychiatric comorbidity in MS, and some of these factors may also be associated with MS.47

We only reviewed studies published in English; however, only 16 publications were excluded because of this, suggesting that this was unlikely to have introduced significant bias. Although diagnostic criteria for MS have changed over time, and the advent of MRI in the 1980s improved diagnosis, we opted to include studies irrespective of time period to gain a more comprehensive view of the world literature. This may have contributed to the high degree of heterogeneity observed; however, this persisted even when we restricted our review to population-based studies and conducted sensitivity analyses.

Psychiatric comorbidity, particularly depression and anxiety, are common in MS. However, the incidence of these and other psychiatric disorders remain under-studied, and study designs were highly heterogeneous. Future comparisons across studies would be enhanced by developing a consistent approach to measuring psychiatric comorbidity, reporting of age-, sex-, and ethnicity-specific estimates, and standardization of estimates to a common (world) population.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tania Gottschalk, BA, MEd, MSc (Librarian, University of Manitoba), who provided assistance regarding the development of the search strategies for this review. This study was conducted under the auspices of the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Drugs in Multiple Sclerosis whose members include Jeffrey Cohen, MD (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, United States), Laura J. Balcer, MD, MSCE (NYU Langone Medical Center, New York City, NY, United States), Brenda Banwell, MD (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, United States), Michel Clanet, MD (Federation de Neurologie, Toulouse, France), Giancarlo Comi, MD (University Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milan, Italy), Gary R. Cutter, PhD (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States), Andrew D. Goodman, MD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, United States), Hans-Peter Hartung, MD (Heinrich-Heine-University, Duesseldorf, Germany), Bernhard Hemmer, MD (Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany), Catherine Lubetzki, MD, PhD (Fédération des maladies du système nerveux et INSERM 71, Paris, France), Fred D. Lublin, MD (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States), Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD (Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Canada), Aaron Miller, MD (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States), David H. Miller, MD (University College London, London, United Kingdom), Xavier Montalban, MD (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain), Paul O’Connor, MD (St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada), Daniel Pelletier, MD (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States), Stephen C. Reingold, PhD (Scientific & Clinical Review Assoc, LLC, Salisbury, CT, United States), Alex Rovira Cañellas, MD (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain), Per Soelberg Sørensen, MD, DMSc (Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark), Maria Pia Sormani, PhD (University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy), Olaf Stuve, MD, PhD (University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Dallas, TX, United States), Alan J. Thompson, MD (University College London, London, United Kingdom), Maria Trojano, MD (University of Bari, Bari, Italy), Bernard Uitdehaag, MD, PhD (VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands), Emmaunelle Waubant, MD, PhD (University of California-San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States), and Jerry S. Wolinsky, MD (University of Texas HSC, Houston, TX, United States).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Ruth Ann Marrie receives research funding from: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, Manitoba Health Research Council, Health Sciences Centre Foundation, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Foundation, Rx & D Health Research Foundation, and has conducted clinical trials funded by Sanofi-Aventis.

Nadia Reider has nothing to declare.

Olaf Stuve is an associate editor of JAMA Neurology, and he serves on the editorial boards of the Multiple Sclerosis Journal, Clinical and Experimental Immunology, and Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. He has participated in data and safety monitoring committees for Pfizer and Sanofi. Dr Stuve has received grant support from Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Jeffrey Cohen reports personal compensation for consulting from EMD Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Innate Immunotherapeutics, Novartis, and Vaccinex. He receives research support paid to his institution from Biogen Idec, Consortium of MS Centers, US Department of Defense, Genzyme, US National Institutes of Health, National MS Society, Novartis, Receptos, Synthon, Teva, and Vaccinex.

Per Soelberg Sørensen has received personal compensation for serving on scientific advisory boards, steering committees, independent data monitoring boards in clinical trials, or speaking at scientific meetings from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Genmab, TEVA, GSK, Genzyme, Bayer Schering, Sanofi-aventis and MedDay Pharmaceuticals. His research unit has received research support from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Teva, Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis, RoFAR, Roche, and Genzyme.

Maria Trojano has served on scientific Advisory Boards for Biogen Idec, Novartis and Merck Serono; has received speaker honoraria from Biogen-Idec, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck-Serono, Teva and Novartis; has received research grants from Biogen-Idec, Merck-Serono, and Novartis.

Gary Cutter has served on scientific advisory boards for and/or received funding for travel from Innate immunity, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, Genzyme, Medimmune, Novartis, Nuron Biotech, Spiniflex Pharmaceuticals, Somahlution, Teva Pharmaceuticals; receives royalties from publishing Evaluation of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (The McGraw Hill Companies, 1984); has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Advanced Health Media Inc, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono Inc, EDJ Associates Inc, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, National Marrow Donor Program, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, and Teva Pharmaceuticals; and has served on independent data and safety monitoring committees for Apotek, Ascendis, Biogen-Idec, Cleveland Clinic, Glaxo Smith Klein Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck/Ono Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Neuren, PCT Bio, Teva, Vivus, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), NINDS, NMSS, and NICHD (OPRU oversight committee).

Stephen Reingold reports personal consulting fees from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), during the conduct of this work; and over the past three years, personal consulting fees from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen Idec, Coronado Biosciences Inc, the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Eli Lilly & Company, from EMD Serono and Merck Serono, Genentech, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals Inc, ISIS Pharmaceuticals Inc, Medimmune Inc, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Observatoire Français de la Sclérosis en Plaques, Opexa Therapeutics, Sanofi-Aventis, SK Biopharmaceuticals, Synthon Pharmaceuticals Inc, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, and Fondation pour l’aide à la Recherche sur la Sclérosis en Plaques, for activities outside of the submitted work.

Funding: This work was supported (in part) by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (US) and a Don Paty Career Development Award from the MS Society of Canada.

Contributor Information

Ruth Ann Marrie, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Manitoba, Canada/Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Canada.

Stephen Reingold, Scientific and Clinical Review Associates, LLC, USA.

Jeffrey Cohen, Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, Cleveland Clinic, USA.

Olaf Stuve, Department of Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, University of Texas Southwestern, USA.

Maria Trojano, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neurosciences and Sense Organs, University of Bari, Italy.

Per Soelberg Sorensen, Department of Neurology, Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, Denmark.

Gary Cutter, Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA.

Nadia Reider, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Canada.

References

- 1. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, et al. Cumulative impact of comorbidity on quality of life in MS. Acta Neurol Scand 2012; 125: 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1997; 54: 531–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Yu BN, et al. Mental comorbidity and multiple sclerosis: Validating administrative data to support population-based surveillance. BMC Neurol 2013; 13: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodgers J, Bland R. Psychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis: A review. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41: 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: Population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005; 65: 1123–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marrie R, Reider N, Cohen J, et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: Overview. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evans C, Beland S, Kulaga S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Americas: A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2013; 40: 195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neyeloff J, Fuchs S, Moreira L. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet: Step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cox DR. The continuity correction. Biometrika 1970; 57: 217–219. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brichetto G, Uccelli MM, Mancardi GL, et al. Symptomatic medication use in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buchanan RJ, Schiffer R, Stuifbergen A, et al. Demographic and disease characteristics of people with multiple sclerosis living in urban and rural areas. Int J MS Care 2006; 8: 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Tai-Seale M, et al. Analyses of nursing home residents with multiple sclerosis and depression using the minimum data set. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 171–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buchanan RJ, Zuniga MA, Carrillo-Zuniga G, et al. A pilot study of Latinos with multiple sclerosis: Demographic, disease, mental health, and psychosocial characteristics. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil 2011; 10: 211–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burns MN, Nawacki E, Siddique J, et al. Prospective examination of anxiety and depression before and during confirmed and pseudoexacerbations in patients with multiple sclerosis. Psychosom Med 2013; 75: 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carta MG, Moro MF, Lorefice L, et al. The risk of bipolar disorders in multiple sclerosis. J Affect Disord 2014; 155: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Demakis GJ, Buchanan R, Dewald L. A longitudinal study of cognition in nursing home residents with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2009; 31: 1734–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Espinola-Nadurille M, Colin-Piana R, Ramirez-Bermudez J, et al. Mental disorders in Mexican patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010; 22: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feinstein A. An examination of suicidal intent in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2002; 59: 674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feinstein A, O’Connor P, Feinstein K. Multiple sclerosis, interferon beta-1b and depression. A prospective investigation. J Neurol 2002; 249: 815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrando SJ, Samton J, Mor N, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in outpatients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2007; 9: 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fisk J, Morehouse SA, Brown MG, et al. Hospital-based psychiatric service utilization and morbidity in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 1998; 25: 230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forbes A, While A, Mathes L, et al. Health problems and health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20: 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Füvesi J, Bencsik K, Losonczi E, et al. Factors influencing the health-related quality of life in Hungarian multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci 2010; 293: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galeazzi G, Ferrari S, Giaroli G, et al. Psychiatric disorders and depression in multiple sclerosis outpatients: Impact of disability and interferon beta therapy. Neurol Sci 2005; 26: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goodin DS. Survey of multiple sclerosis in northern California. Northern California MS Study Group. Mult Scler 1999; 5: 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goretti B, Ghezzi A, Portaccio E, et al. Psychosocial issue in children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2010; 31: 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harel Y, Barak Y, Achiron A. Dysregulation of affect in multiple sclerosis: New phenomenological approach. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 61: 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holper L, Coenen M, Weise A, et al. Characterization of functioning in multiple sclerosis using the ICF. J Neurol 2010; 257: 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hopman WM, Coo H, Edgar CM, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 2007; 34: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horton M, Rudick RA, Hara-Cleaver C, et al. Validation of a self-report comorbidity questionnaire for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 2010; 35: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janardhan V, Bakshi R. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: The impact of fatigue and depression. J Neurol Sci 2002; 205: 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joffe RT, Lippert GP, Gray TA, et al. Mood disorder and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1987; 44: 376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kang JH, Chen YH, Lin HC. Comorbidities amongst patients with multiple sclerosis: A population-based controlled study. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lehan T, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Macias MÁ, et al. Distress associated with patients’ symptoms and depression in a sample of Mexican caregivers of individuals with MS. Rehabil Psychol 2012; 57: 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leonavicius R, Adomaitiene A. Impact of depression on multiple sclerosis patients. Cent Eur J Med 2012; 7: 685–690. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leonavicius R, Adomaitiene A, Leskauskas D. The relationships between depression and life activities and well-being of multiple sclerosis patients. Cent Eur J Med 2011; 6: 652–661. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levinthal DJ, Rahman A, Nusrat S, et al. Adding to the burden: Gastrointestinal symptoms and syndromes in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2013; 2013: 319201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marrie RA, Horwitz RI, Cutter G, et al. The burden of mental comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: Frequent, underdiagnosed, and under-treated. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marrie RA, Horwitz RI, Cutter G, et al. Association between comorbidity and clinical characteristics of MS. Acta Neurol Scand 2011; 124: 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marrie RA, Yu BN, Leung S, et al. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid disease do not differ in the multiple sclerosis and general populations: A validation study using administrative data. Neuroepidemiology 2012; 39: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McGuigan C, Hutchinson M. Unrecognised symptoms of depression in a community-based population with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2006; 253: 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, et al. Screening for depression among patients with multiple sclerosis: Two questions may be enough. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nuyen J, Schellevisa FG, Satarianob WA, et al. Comorbidity was associated with neurologic and psychiatric diseases: A general practice-based controlled study. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 1274–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pandya R, Metz L, Patten SB. Predictive value of the CES-D in detecting depression among candidates for disease-modifying multiple sclerosis treatment. Psychosomatics 2005; 46: 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patten SB, Berzins S, Metz LM. Challenges in screening for depression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 1406–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patten SB, Fridhandler S, Beck CA, et al. Depressive symptoms in a treated multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patten SB, Metz LM, Reimer MA. Biopsychosocial correlates of lifetime major depression in a multiple sclerosis population. Mult Scler 2000; 6: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al. Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1996; 46: 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Scott TF, Allen D, Price TR, et al. Characterization of major depression symptoms in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8: 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Simioni S, Ruffieux C, Bruggimann L, et al. Cognition, mood and fatigue in patients in the early stage of multiple sclerosis. Swiss Med Wkly 2007; 137: 496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tarrants M, Oleen-Burkey M, Castelli-Haley J, et al. The impact of comorbid depression on adherence to therapy for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int 2011; 2011: 271321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thielscher C, Thielscher S, Kostev K. The risk of developing depression when suffering from neurological diseases. Ger Med Sci 2013; 11: Doc02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Valleroy ML, Kraft GH. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1984; 65: 125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zabad RK, Patten SB, Metz LM. The association of depression with disease course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005; 64: 359–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zorzon M, de Masi R, Nasuelli D, et al. Depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis. A clinical and MRI study in 95 subjects. J Neurol 2001; 248: 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Beiske AG, Svensson E, Sandanger I, et al. Depression and anxiety amongst multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol 2008; 15: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brajković L, Bras M, Milunović V, et al. The connection between coping mechanisms, depression, anxiety and fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Coll Antropol 2009; 33 (Suppl 2): 135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. da Silva AM, Vilhena E, Lopes A, et al. Depression and anxiety in a Portuguese MS population: Associations with physical disability and severity of disease. J Neurol Sci 2011; 306: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dahl OP, Stordal E, Lydersen S, et al. Anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis. A comparative population-based study in Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 1495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Espinola-Nadurille M, Colin-Piana R, Ramirez-Bermudez J, et al. Mental disorders in Mexican patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010; 22: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Foroughipour M, Behdani F, Hebrani P, et al. Frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study. J Res Med Sci 2012; 17: 248–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Garfield AC, Lincoln NB. Factors affecting anxiety in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2012; 34: 2047–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gold SM, Schulz H, Mönch A, et al. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis does not affect reliability and validity of self-report health measures. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, et al. Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2009; 30: 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hakim EA, Bakheit AM, Bryant TN, et al. The social impact of multiple sclerosis—a study of 305 patients and their relatives. Disabil Rehabil 2000; 22: 288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, et al. Anxiety and depression influence the relation between disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kehler MD, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Is health anxiety a significant problem for individuals with multiple sclerosis? J Behav Med 2009; 32: 150–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Korostil M, Feinstein A. Anxiety disorders and their clinical correlates in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Leonavicius R, Adomaitiene A. Anxiety and social activities in multiple sclerosis patients. Cent Eur J Med 2013; 8: 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Merlino G, Fratticci L, Lenchig C, et al. Prevalence of ‘poor sleep’ among patients with multiple sclerosis: An independent predictor of mental and physical status. Sleep Med 2009; 10: 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Montel SR, Bungener C. Coping and quality of life in one hundred and thirty five subjects with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moreau T, Schmidt N, Joyeux O, et al. Coping strategy and anxiety evolution in multiple sclerosis patients initiating interferon-beta treatment. Eur Neurol 2009; 62: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nicholl CR, Lincoln NB, Francis VM, et al. Assessment of emotional problems in people with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil 2001; 15: 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Poder K, Ghatavi K, Fisk J, et al. Social anxiety in a multiple sclerosis clinic population. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Porcel J, Río J, Sánchez-Betancourt A, et al. Long-term emotional state of multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta. Mult Scler 2006; 12: 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Siepman TA, Janssens AC, de Koning I, et al. The role of disability and depression in cognitive functioning within 2 years after multiple sclerosis diagnosis. J Neurol 2008; 255: 910–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smith SJ, Young CA. The role of affect on the perception of disability in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil 2000; 14: 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Spain LA, Tubridy N, Kilpatrick TJ, et al. Illness perception and health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2007; 116: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Till C, Udler E, Ghassemi R, et al. Factors associated with emotional and behavioral outcomes in adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 1170–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wood B, van der Mei I, Ponsonby AL, et al. Prevalence and concurrence of anxiety, depression and fatigue over time in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Eaton WW, Pedersen MG, Nielsen PR, et al. Autoimmune diseases, bipolar disorder, and non-affective psychosis. Bipolar Disord 2010; 12: 638–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Edwards LJ, Constantinescu CS. A prospective study of conditions associated with multiple sclerosis in a cohort of 658 consecutive outpatients attending a multiple sclerosis clinic. Mult Scler 2004; 10: 575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bombardier CH, Blake KD, Ehde DM, et al. Alcohol and drug abuse among persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2004; 10: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lindegard B. Diseases associated with multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand 1985; 71: 267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, et al. High frequency of adverse health behaviors in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sheu JJ, Lin HC. Association between multiple sclerosis and chronic periodontitis: A population-based pilot study. Eur J Neurol 2013; 20: 1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Turner AP, Hawkins EJ, Haselkorn JK, et al. Alcohol misuse and multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fisk JD, Morehouse SA, Brown MG, et al. Hospital-based psychiatric service utilization and morbidity in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 1998; 25: 230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fromont A, Binquet C, Rollot F, et al. Comorbidities at multiple sclerosis diagnosis. J Neurol 2013; 260: 2629–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. McCrone P, Heslin M, Knapp M, et al. Multiple sclerosis in the UK: Service use, costs, quality of life and disability. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26: 847–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Descriptive epidemiology of affective disorders in multiple sclerosis. CNS Spectr 2005; 10: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Disability in a community population with MS with and without mental disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 2012; 43: 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Alschuler KN, Jensen MP, Ehde DM. The association of depression with pain-related treatment utilization in patients with multiple sclerosis. Pain Med 2012; 13: 1648–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Amato MP, Ponziani G, Rossi F, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: The impact of depression, fatigue and disability. Mult Scler 2001; 7: 340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Avasarala JR, Cross AH, Trinkaus K. Comparative assessment of Yale Single Question and Beck Depression Inventory Scale in screening for depression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2003; 9: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bamer AM, Cetin K, Johnson KL, et al. Validation study of prevalence and correlates of depressive symptomatology in multiple sclerosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008; 30: 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baumstarck-Barrau K, Simeoni MC, Reuter F, et al. Cognitive function and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol 2011; 11: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bodini B, Mandarelli G, Tomassini V, et al. Alexithymia in multiple sclerosis: Relationship with fatigue and depression. Acta Neurol Scand 2008; 118: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Brown RF, Valpiani EM, Tennant CC, et al. Longitudinal assessment of anxiety, depression, and fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Psychother 2009; 82(Pt 1): 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Cetin K, Johnson KL, Ehde DM, et al. Antidepressant use in multiple sclerosis: Epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, et al. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: Epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 1862–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Einarsson U, Gottberg K, Fredrikson S, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Stockholm County. A pilot study exploring the feasibility of assessment of impairment, disability and handicap by home visits. Clin Rehabil 2003; 17: 294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ghajarzadeh M, Sahraian MA, Fateh R, et al. Fatigue, depression and sleep disturbances in Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Med Iran 2012; 50: 244–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Gottberg K, Einarsson U, Fredrikson S, et al. A population-based study of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis in Stockholm county: Association with functioning and sense of coherence. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Isaksson AK, Gunnarsson LG, Ahlström G. The presence and meaning of chronic sorrow in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Johansson S, Ytterberg C, Claesson IM, et al. High concurrent presence of disability in multiple sclerosis. Associations with perceived health. J Neurol 2007; 254: 767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Johansson S, Ytterberg C, Hillert J, et al. A longitudinal study of variations in and predictors of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79: 454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Jonsson A, Dock J, Ravnborg MH. Quality of life as a measure of rehabilitation outcome in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1996; 93: 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Julian LJ, Vella L, Frankel D, et al. ApoE alleles, depression and positive affect in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 311–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kargarfard M, Eetemadifar M, Mehrabi M, et al. Fatigue, depression, and health-related quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ketelslegers IA, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Boon M, et al. Fatigue and depression in children with multiple sclerosis and monophasic variants. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2010; 14: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Khan F, Pallant J, Brand C. Caregiver strain and factors associated with caregiver self-efficacy and quality of life in a community cohort with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1241–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Klevan G, Jacobsen CO, Aarseth JH, et al. Health related quality of life in patients recently diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2014; 129: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Lobentanz IS, Asenbaum S, Vass K, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: Disability, depressive mood, fatigue and sleep quality. Acta Neurol Scand 2004; 110: 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Lutterotti A, Vedovello M, Reindl M, et al. Olfactory threshold is impaired in early, active multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2011; 17: 964–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Maor Y, Olmer L, Mozes B. The relation between objective and subjective impairment in cognitive function among multiple sclerosis patients—the role of depression. Mult Scler 2001; 7: 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Mattioli F, Bellomi F, Stampatori C, et al. Depression, disability and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: A cross sectional Italian study. Neurol Sci 2011; 32: 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Noy S, Achiron A, Gabbay U, et al. A new approach to affective symptoms in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36: 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Patten SB, Lavorato DH, Metz LM. Clinical correlates of CES-D depressive symptom ratings in an MS population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005; 27: 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Patti F, Cacopardo M, Palermo F, et al. Health-related quality of life and depression in an Italian sample of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci 2003; 211: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Patti F, Pozzilli C, Montanari E, et al. Effects of education level and employment status on HRQoL in early relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Pittion-Vouyovitch S, Debouverie M, Guillemin F, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is related to disability, depression and quality of life. J Neurol Sci 2006; 243: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Romberg A, Ruutiainen J, Puukka P, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis patients during inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 30: 1480–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Seyed Saadat SM, Hosseininezhad M, Bakhshayesh B, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depression in Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Neurol Sci 2014; 35: 735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Sollom AC, Kneebone Treatment of depression in people who have multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Sundgren M, Maurex L, Wahlin A, et al. Cognitive impairment has a strong relation to nonsomatic symptoms of depression in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2013; 28: 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Tanriverdi D, Okanli A, Sezgin S, et al. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis in Turkey: Relationship to depression and fatigue. J Neurosci Nurs 2010; 42: 267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Vogt A, Kappos L, Calabrese P, et al. Working memory training in patients with multiple sclerosis—comparison of two different training schedules. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2009; 27: 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Williams RM, Turner AP, Hatzakis M, Jr, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression among veterans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005; 64: 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Zettl UK, Bauer-Steinhusen U, Glaser T, et al. Evaluation of an electronic diary for improvement of adherence to interferon beta-1b in patients with multiple sclerosis: Design and baseline results of an observational cohort study. BMC Neurol 2013; 13: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, et al. The regional distribution of anxiety disorders: Implications for the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2010. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. Epub ahead of print 22 July 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Irwin MR, Miller AH. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain Behav Immun 2007; 21: 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Lotrich FE, El-Gabalawy H, Guenther LC, et al. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of depression: Different treatments and their effects. J Rheumatol 2011; 88: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Feinstein A. Multiple sclerosis and depression. Mult Scler 2011; 17: 1276–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Yadav R, Zigmond AS. Temporal lobe lesions and psychosis in multiple sclerosis. BMJ Case Rep 2010; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Minden SL, Orav J, Schildkraut JJ. Hypomanic reactions to ACTH and prednisone treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1988; 38: 1631–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Ciriaco M, Ventrice P, Russo G, et al. Corticosteroid-related central nervous system side effects. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2013; 4 (Suppl 1): S94–S98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.