Abstract

While we previously reported a striking racial difference in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive oropharyngeal cancer (OPSCC), less is known about differences in outcomes and trends over time in OPSCC by HPV status and race. We conducted a retrospective analysis of 467 OPSCC patients treated at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center between 1992 and 2007, of which 200 had tissue available for HPV16 testing. HPV16 positive patients were significantly more likely to be white, with 45.5% of whites and 15.5% of blacks testing positive for HPV16. There was a significant increase in HPV16 positive OPSCC for all patients over time from 15.6% in 1992-1995 to 43.3% in 2004-2007 (p=.01). From 1992-1995, 33% of white patients were HPV16 positive with no black patients positive. From 2004-2007, 17.7% of black patients and 54% of white patients were HPV16 positive. White and black patients with HPV16 positive tumors had an identical and favorable overall survival (OS)(median 8.1 and 8.1 years, respectively ). However among HPV16 negative patients, whites had an improved OS compared to blacks (median 2.3 vs. 0.9 years, respectively, p = .02) including when analyzed in a multivariable Cox regression model. From 1992 to 2007 the percentage of HPV16 positive OPSCCs increased for white patients and was seen for the first time in black patients. While survival for HPV positive black and white patients was similar and favorable, outcomes for HPV negative patients were poor, with blacks having worse survival even after controlling for baseline characteristics.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, head and neck cancer, race, survival, prevalence

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC) spans diverse anatomic sites including the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx and nasopharynx. While traditional risk factors for HNSCC include smoking and alcohol it has become apparent over the last 2-3 decades that the human papillomavirus (HPV) has an etiological role in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx (OPSCC), with predilection for tumors involving the base of tongue or tonsils.(1, 2) HPV positive OPSCC has a distinct clinical phenotype occurring predominantly in non smokers and non drinkers of male sex and younger age than HPV negative OPSCC.(1-3) Although these tumors are more often poorly differentiated with basaloid features and patients typically present in stage III and IV with more advanced nodal stage,(4, 5) HPV positive oropharyngeal cancers have been shown to be more responsive to therapy with improved outcome. (6-9)

Recent analyses of HPV positive OPSCC have shown significant disparities by race between black and white patients.(10-13) Our group analyzed 237 specimens available from patients treated on the TAX 324 trial, and showed that whites had a significantly higher proportion of HPV16 positive tumors compared to black patients (34% vs. 4%, p<.001).(11) More recently, Chernock et al examined the biopsy specimens of 174 stage III/IV OPSCC patients and found a significantly higher percentage of white patients tested positive for high risk HPV (63.5% vs. 11.5%, p = <.001) or p16 (83.1% vs. 34.6%, p <.001) compared to black patients.(10)

While disparities in the percentage of HPV positive OPSCC have been reported, fewer data exists on trends over time in HPV positive OPSCC by race. Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Residual Tissue Repositories Program, Chartuvedi et al. observed an increase in prevalence of HPV16 positive OPSCC over time for both whites and blacks from 1984 to 2004, with this trend reaching significance only for whites (p=<0.001).(3) Other studies have looked at changes in incidence HPV positive OPSCC over time by race, however HPV positive HNSCC was inferred based on potentially associated anatomic locations including the base of tongue, tonsils, or other sites in the oropharynx. (14, 15)

In order to further investigate changes over time in the percentage of HPV16 positive OPSCC between black and white patients, we analyzed tissue samples from oropharyngeal cancer patients treated here at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center (UMGCC) over a 15 year time period.

Materials and Methods

After IRB approval we performed a retrospective chart review of data from patients treated at UMGCC for HNSCC from 1992 to 2007. We identified 467 cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy. Data collected included race, gender, age at diagnosis, smoking status, alcohol use, disease occurrence (first primary, second primary, or recurrence), tumor stage, nodal stage, overall staging, treatment received, and year of diagnosis. Baseline characteristics were obtained through chart review and gender, race, and smoking and drinking status were based on patient reporting. TNM staging(16) was used to define tumor, nodal and overall staging. Any missing values were recorded as unknown. Of the 467 cases, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue was available for HPV16 testing from 200 patients.

DNA extraction from FFPE tissue blocks

Tissue sections were reviewed by a pathologist to guide core punches containing primarily tumor tissue. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA was quantified using the Quant-iT dsDNA Assay Kit, High Sensitivity (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) and stored at −80°C in aliquots.

HPV16 PCR

PCR was performed for the E6 (forward ATGTTTCAGGACCCACAGGA, reverse CAGCTGGGTTTCTCTACGTGTT) and E7 (forward ATGCATGGAGATACACCTAC, reverse CATTAACAGGTCTTCCAAAG) genes of HPV16. Using 2 ng DNA, 40 cycles of standard three-step PCR (annealing temperature 55°C) was performed. A negative control (no DNA) was included in every PCR run. Only cases positive for both genes were scored HPV16 positive. Cases that were discordant between the genes were excluded. In the case of ambiguity interpreting either gene, both genes were amplified again from a freshly diluted DNA aliquot using a different primer set (overlapping but not nested with the original primer set). Cases that remained ambiguous were excluded. HPV16 status could be scored for 194 of 200 cases.

While other HPV types, including HPV-18, 31, 33, and 35, can also be found in OPSCC, HPV16 accounts for the majority of cases of HPV associated OPSCC, accounting for upwards of 87% of cases worldwide.(17) In order to ensure we were not missing a significant amount of other HPV types we performed an exploratory analysis of HPV 16 negative tumor samples from 27 black patients. HPV genotyping on these DNA samples was performed using the LINEAR ARRAY® HPV Genotyping Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA), which tests for 37 high and low risk HPV types.

Statistical Methodology

Baseline characteristics were compared between the 200 patients with tissue available for HPV16 testing and the remainder of the OPSCC patient population (N= 267) using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. For the 200 patients with known HPV16 status the Fisher’s exact and the Fisher-Freeman-Halton with Monte Carlo simulations tests were used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics between HPV16 positive and HPV16 negative patients, HPV16 positive whites versus HPV16 positive black patients, HPV16 positive white patients versus HPV16 negative white patients, and HPV16 positive black patients versus HPV16 negative black patients. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test. Patients with unknown status or value of a characteristic were excluded from tables and the corresponding and relevant analysis. All statistical tests were 2-sided and done at 0.05 Type I error.

OS functions were estimated and compared using the Kaplan-Meier approach and the log-rank tests. The univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were applied to identify possible predictors as well as the magnitude of their effect on survival parameters (HR, hazard of death). OS was defined from the date of diagnosis until the date of death from any cause or censored at the date last known alive. Median OS times with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. The homogeneity test was applied for multiple (4) stratified 2×2 tables to assess whether odds-ratios (ORs) for acquiring HPV16 positive status across 4 distinct time periods were constant. Due to the estimated common odds ratio across these 4 time periods, the second common odds-ratio test was used to estimate and compare odds ratio for distinct ethnic groups of patients. Statistical analyses were conducted using S-plus (TIBCO, v. 8.2) and StatXact (Cytel st., v.8.0).

Results

A total of 467 OPSCC patients were identified between 1992 and 2007, and 200 of these patients had tissue available for testing for HPV16. The median age of the tested population was 56, 81% of patients were male, and racial distribution was 62.5% white, 36.5% black and 1% other races. The majority of cases (93.5%) represented a first primary diagnosis, with most patients presenting with locally advanced disease with 62% presenting as Stage IVA. The largest proportion of our patients (47%) were treated with chemoradiation alone. Compared to our entire population of OPSCC, the tested patients were younger, and more likely to consume alcohol or both alcohol and tobacco. (Supplemental table 1).

Out of patients with tissue available for testing, 67 (33%) were positive for HPV16, 127 (64%) were negative, and 6 (3%) could not be analyzed for technical reasons. Comparison of HPV16 positive versus negative patients is shown in Table 1. Patients with HPV16 associated OPSCCs were significantly more likely to be white and male, and were significantly less likely to be smokers, drinkers, or both smokers and drinkers. They also had a significantly lower tumor (T) stage and higher nodal (N) stage compared to their HPV16 negative counterparts. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between white and black HPV16 positive patients (Supplemental Table 2). Compared with HPV16 negative white patients, HPV16 negative black patients were significantly younger, and more likely to be male, drinkers, and combined drinkers and smokers (Table 2).

Table 1.

Selected Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the HPV16 positive and HPV16 negative patients

| Baseline Characteristics* | HPV16 positive N= 67 | HPV16 negative N= 127 | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Race | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 56 (83.6%) | 67 (52.8%) | |

| Black | 10 (14.9%) | 59 (46.5%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

|

| |||

| Gender | 0.03 | ||

| Male | 60 (89.6%) | 97 (76.4%) | |

| Female | 7 (10.4%) | 30 (23.6%) | |

|

| |||

| Age | 0.2 | ||

| Median | 54 | 56 | |

| Range | 36-84 | 35-93 | |

|

| |||

| Smoking | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 49 (73.1%) | 110 (86.6%) | |

| No | 12 (17.9%) | 9 (7%) | |

|

| |||

| Alcohol | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 33 (49.3%) | 98 (77.2%) | |

| No | 28 (41.8%) | 21 (16.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Both Smoking and Alcohol | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 30 (44.8%) | 96 (75%) | |

| No | 31 (46.3%) | 23 (18%) | |

|

| |||

| Occurrence | 0.14 | ||

| First Primary | 66 (98.5%) | 115 (90.6%) | |

| Other Primary | 1 (1.5%) | 7 (5.5%) | |

| Relapse | 0 | 5 (3.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Tumor stage | <0.0001 | ||

| T1 | 12 (17.9%) | 7 (5.5%) | |

| T2 | 18 (26.9%) | 19 (14.9%) | |

| T3 | 22 (32.8%) | 33 (25.9%) | |

| T4 | 9 (13.4%) | 57 (44.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Nodal Stage | 0.002 | ||

| N0 | 5 (7.5%) | 37 (29.1%) | |

| N1 | 6 (9%) | 16 (12.6%) | |

| N2 | 43 (64.2%) | 56 (44%) | |

| N3 | 10 (14.9%) | 11 (8.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Overall Stage | 0.22 | ||

| I | 0 | 6 (4.7%) | |

| II | 2 (3%) | 6 (4.7%) | |

| III | 6 (9%) | 22 (17.3%) | |

| IVA | 46 (68.7%) | 75 (59%) | |

| IVB | 9 (13.4%) | 12 (9.5%) | |

| IVC | 1 (1.5%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

|

| |||

| Treatment | 0.21 | ||

| Chemoradiation | 36 (53.7%) | 55 (43.3%) | |

| Radiation | 8 (11.9%) | 25 (19.7%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 1 (1.5%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| Surgery | 2 (3%) | 18 (14.2%) | |

| Radiotherapy + Surgery | 9 (13.4%) | 6 (4.7%) | |

| Chemoradiation + Surgery | 5 (7.5%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

patients with unknown status of a characteristic were excluded from the relevant statistical analysis.

p-values were calculated with the use of two-sided exact or with Monte Carlo simulations

Fisher’s and Fisher-Freeman-Halton’s tests were used for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Selected Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the HPV16 negative black and HPV16 negative white patients

| Baseline characteristics* | HPV16 Negative Black Patients N = 59 | HPV16 Negative White Patients N=67 | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | 0.03 | ||

| Male | 50 (84.8%) | 46 (68.7%) | |

| Female | 9 (15.2) | 21 (31.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Age | 0.02 | ||

| Median | 53 | 60 | |

| Range | 35-84 | 39-93 | |

|

| |||

| Smoking | 0.17 | ||

| Yes | 54 (91.5%) | 55 (82.1%) | |

| No | 2 (3.4%) | 7 (10.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Drinking | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 51 (86.4%) | 47 (70.2%) | |

| No | 5 (8.5%) | 15 (22.4%) | |

|

| |||

| Both Smoking and Drinking | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 51 (86.4%) | 45 (67.2%) | |

| No | 5 (8.5%) | 17 (25.4%) | |

|

| |||

| Occurrence | 0.45 | ||

| First Primary | 56 (95%) | 59 (88%) | |

| Other Primary | 2 (3.4%) | 5 (7.5%) | |

| Relapse | 1 (1.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Tumor stage | 0.17 | ||

| T1 | 3 (5.1%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| T2 | 6 (10.2%) | 12 (17.9%) | |

| T3 | 14 (23.7%) | 19 (28.4%) | |

| T4 | 34 (57.6%) | 23 (34.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Nodal stage | 0.14 | ||

| N0 | 13 (22%) | 23 (34.3%) | |

| N1 | 7 (11.8%) | 9 (13.4%) | |

| N2 | 30 (50.9%) | 26 (38.8%) | |

| N3 | 8 (13.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Overall Staging | 0.56 | ||

| I | 2 (3.4%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| II | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| III | 10 (16.9%) | 12 (17.9%) | |

| IVa | 36 (61%) | 39 (58.2%) | |

| IVb | 8 (13.6%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| IVc | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Treatment | 0.22 | ||

| Chemoradiation | 29 (49.2%) | 26 (38.8%) | |

| Radiation | 15 (25.4%) | 10 (14.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Surgery | 4 (6.8%) | 13 (19.4%) | |

| Radiotherapy + Surgery | 3 (5.1%) | 3 (4.5%) | |

| Chemoradiation + Surgery | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

patients with unknown status of a characteristic were excluded from the corresponding and relevant statistical analysis.

p-values were calculated with the use of two-sided exact or with Monte Carlo simulations

Fisher’s or Fisher-Freeman-Halton’s tests were used for categorical variables, and the two-sample t-test for continuous variables.

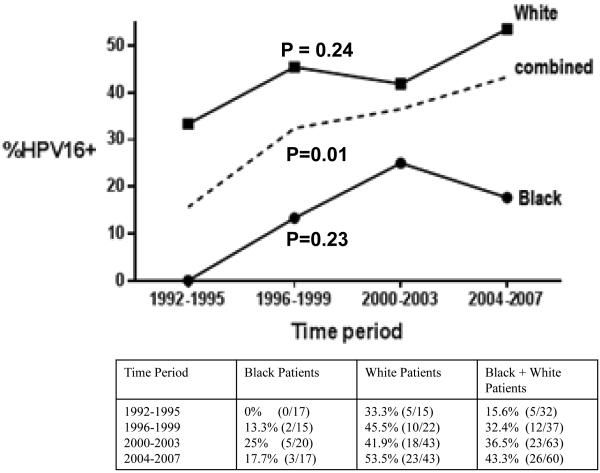

Differences in percentage of HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancers by race were evaluated over time, from 1992 until 2007. For each four year time period examined, whites had a significantly higher percentage of HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancers compared to blacks (p<0.0001). When our entire cohort of tested oropharyngeal patients was analyzed there was a significant increase in the percentage of HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancers over time from 15.6% in 1992-1995 to 43.3% in 2004-2007 (p=.01) (Figure 1). However when trends over time for each individual race were examined, while both exhibited an increase in the percentage of HPV16 positive patients over time, neither of these trends reached significance (Figure 1). Importantly, we observed the emergence of HPV16 positive OPSCC in blacks treated at UMGCC between 1992 and 2007, increasing from no cases in 1992-1995 to 17.7% of OPSCC in 2004-2007.

Figure 1.

Changes in Percentage of HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Cancers over Time by Race * ^

* P-values Listed are for Comparison of Change in Percentage of HPV Positive OPSCC between 1992 and 2007 for Black, White and Black and White Patients together

^ Percentage of HPV16 positive patients (Total number of HPV positive patients/total number of patients during time period) by race over each time period shown below graph

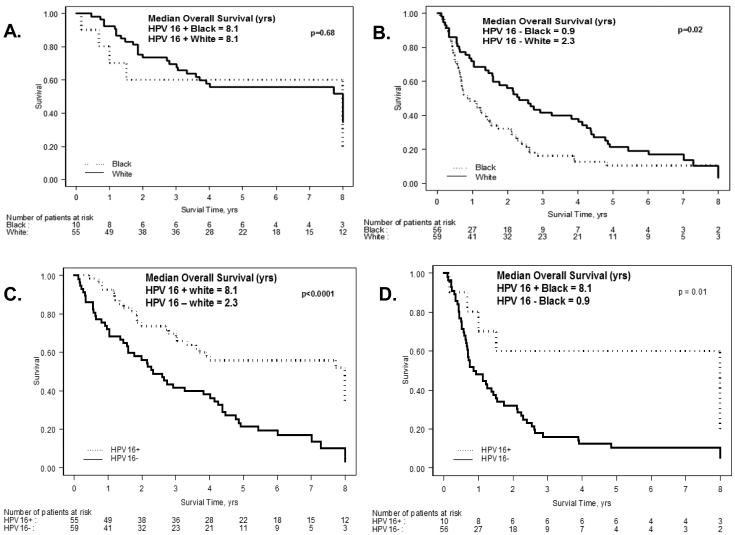

Survival was analyzed in patients tested for HPV16 with a first primary (n = 187). Blacks had a significantly worse survival compared to all whites (HR=1.9; 95% CI: 1.4-2.7, p = .0002) and HPV16 positive patients had a significantly better overall survival compared to HPV16 negative patients (median OS 8.1 vs. 1.5 years, p <0.0001). Survival analysis by race and HPV16 status is shown in Figure 2. Both white HPV16 positive and black HPV16 positive patients had a significantly better overall survival compared to their respective white and black HPV negative cohorts (Figure 2C and 2D respectively). While there were no differences in overall survival between HPV positive black and HPV positive white patients (median OS 8.1 vs. 8.1 years) (Figure 2A), HPV negative whites had a significantly better overall survival compared to HPV negative black patients (median OS 2.3 vs. 0.9 years, p = 0.02) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Overall Survival Functions

A. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival According to Ethnic Group in HPV 16 Positive Patients.

B. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival According to Ethnic Group in HPV 16 Negative Patients.

C. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival According to HPV Status in White Patients.

D. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival According to HPV Status in Black Patients.

*Overall Survival Profiles were truncated at 8 years

A multivariable Cox regression model was used to assess whether differences in characteristics between patients tested for HPV16 (Table 3) and between black and white HPV16 negative patients (Table 4) accounted for the survival differences between these groups. Race, age, gender, overall stage, and smoking and drinking were included in the model. Amongst the entire tested population all factors except for stage were significantly associated with survival, with race and HPV status having the strongest association. Amongst HPV negative patients race was highly significant when controlling for these other factors (p = 0.007) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Results of the Multivariable Cox Step Wise* Regression Model for Patients who were Tested for HPV (n=149**)

| Risk factor | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.004-1.050) | 0.02+ |

|

| ||

| Race | 0.003 | |

| White | 1.0^ | |

| Black | 1.9 (1.25-2.90) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | 0.04 | |

| M | 1.0 | |

| F | 1.7 (1.02-2.73) | |

|

| ||

| Smoking and drinking | 0.03 | |

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.06-2.92) | |

|

| ||

| HPV16 Status | 0.003 | |

| Positive | 1.0 | |

| Negative | 2.1 (1.30-3.44) | |

Two probabilities 0.25 and 0.15 were selected for entering and staying in the model, respectively.

testing for non-linearity was done, p-value=0.13.

These 149 patients had complete records and therefore were entered into multivariable regression model.

A reference category

Table 4.

Results of the Multivariable Cox Regression Model for HPV Negative Patients (n = 104*)

| Risk Factor | n | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age+ | 104 | 1.0 (1.01-1.06) | 0.007 |

|

| |||

| Race | 0.003 | ||

| White | 52 | 1.0** | |

| Black | 52 | 2.0 (1.28-3.14) | |

|

| |||

| Gender | 0.052 | ||

| M | 79 | 1.0 | |

| F | 25 | 1.6 (0.99-2.69) | |

|

| |||

| Smoking and Drinking | 0.29 | ||

| No | 17 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 87 | 1.4 (0.75-2.56) | |

|

| |||

| Overall Stage | 1.1 (0.84-1.40) | 0.51 | |

| I | 3 | ||

| II | 3 | ||

| III | 19 | ||

| IVa | 65 | ||

| IVb | 11 | ||

| IVc | 3 | ||

testing for non-linearity for variable age was done, p-value=0.11.

Patients with complete records and therefore were entered into multivariable regression model.

Reference category.

As described in the methods section, given the low number of HPV16 positive black patients, in order to ensure we were not missing a significant amount of other HPV types we analyzed HPV16 negative tumor samples from 27 black patients using LINEAR ARRAY® HPV Genotyping Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA), to evaluate for 37 high and low risk HPV strains. With appropriate positive controls, we detected only one other HPV strain (HPV 58) in a single patient.

Discussion

Our study uniquely evaluated changes over time in percentage of HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancers between white and black patients based on pathologic confirmation of HPV status. In our entire population of patients there was a significant increase in HPV16 positive OPSCC over time. While the increase in percentage of HPV16 positive OPSCC was not significant when white and black patients were analyzed separately, importantly, during this time period we observed the emergence of HPV16 positive OPSCC in black patients treated at UMGCC, increasing from no cases in 1992-1995 to 17.7% of black OPSCC cases in 2004-2007.

To our knowledge only one other study has examined prevalence of HPV positive OPSCC over time by race with HPV status confirmed by analysis of tumor samples. In this study, Chartuvedi et al, examined specimens from the SEER Repositories Tissue Program and observed a significant increase in the prevalence of HPV positive OPSCC in whites from 20% to over 60% from 1984 to 2004. With a total of 50 HPV positive OPSCC black patients found during the years examined, they observed the emergence and subsequent increase in prevalence in blacks, with an increase from no cases in 1984-1989 to 20% in 1995-1999. However this trend did not reach statistical significance.(3) Although our data was from a single institution in one geographic region we similarly observed an increase in HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancers in whites and the emergence (albeit approximately 6 years later than by SEER data) and subsequent increase of HPV16 positive OPSCC in black patients between 1992 and 2007. Our ability to detect a significant difference for each individual race is limited by a smaller sample size including only 10 HPV16 positive black patients found during the years studied. Our results also showed that for all time periods between 1992 and 2007, white patients had a significantly higher percentage of HPV16 positive tumors. Confirming our initial work as well as subsequent studies,(10-13, 18, 19) we found that HPV16 positive oropharyngeal cancer is significantly more common in whites compared to blacks.

Risk factors for HPV positive OPSCC include increased number of vaginal, oral, and oral-anal sexual partners, leading to increased exposure and subsequent infection of oropharyngeal tissue.(2, 18, 20) Increasing trends of HPV related disease over time have been attributed to changes in sexual practices over the previous decades including: increasing number of sexual partners, decreased age at sexual debut, as well an increase in number of people performing oral sex.(21, 22). Differences in the prevalence of HPV positive OPSCC between blacks and whites may be partially attributed to differences in sexual practices with whites engaging in more oral-genital sex compared to blacks.(23, 24) Data from interviews conducted during a national survey of adolescent males in the United states ages 15-19, showed that 42% of white males had performed oral sex on a female compared to only 21% of black males. Black males had a significant change in percentage that received oral sex from a female increasing 25% to 57% from 1988 to 1995, while there was no significant change over the same time period in white males (48 to 50%) in this study.(23) Similarly, data from the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) that included over 4000 patients, found that across all age cohorts white men and women were significantly more likely to have ever performed oral sex than other races. White men for example were significantly more likely to have performed oral sex at sexual debut (43.5% vs. 17.6%, p<0.001) and have >5 lifetime oral sex partners (38.8% vs. 20.7%, p<0.0001). Although blacks reported less oral sexual behaviors, in both blacks and whites younger age cohorts (20-29 and 30-44) were more likely to have ever performed oral sex compared to older age cohorts (45-59 and 60-69).(25) Increased oral sex behaviors in whites may partially explain the consistent disparity in prevalence of HPV positive OPSCC by race. While more data is needed on changes in sexual behaviors over time by race, the delayed emergence of HPV positive OPSCC compared to whites and our observation of an increasing prevalence of HPV16 positive OPSCC in blacks in more recent years, may reflect changes in sexual practices over time in blacks.

Despite the differences in oral sexual behaviors described above, no disparity in prevalence of oral HPV infection was found in the NHANES cohort.(25, 26) In a cross sectional study as part of NHANES, which involved evaluating oral rinse samples in healthy adults for HPV DNA of oral exfoliated cells, a trend towards a significantly higher prevalence of any oral HPV infection was seen in black versus white participants (10.5% vs. 6.5%, respectively, p = .06), with only a small disparity in oral HPV16 infection (2.4% in whites vs. 1.9% in blacks), and race was not independently associated with oral HPV infection after controlling for sexual behavior.(25, 26) This suggests that differences in sexual practice accounting for higher exposure in white patients do not appear to lead to significant differences in the prevalence of oral HPV infection between blacks and whites. Surprisingly, despite similar rates of HPV infection, HPV positive OPSCC is at least 3 fold more common in whites compared to blacks.(3, 10, 11, 13) This suggests that other not yet defined factors which may influence the persistence of oral HPV infection and the subsequent development of cancer following HPV infection, may also contribute to the racial disparity in HPV associated OPSCC. In fact, a study of 140 patients showed that whites were significantly more likely to have HPV “active” HNSCC (defined as HPV DNA positive and p16 positive) compared to blacks(27), as growing data suggests that it is in tumors in which both HPV and p16 are positive, that HPV is the driver of oncogenesis leading to an improved prognosis.(28, 29) Further research is needed to determine the reasons for a consistently higher proportion of HPV associated OPSCC among white patients compared to black.

Similar to the experience in the literature, our HPV16 positive patients had a significantly improved overall survival compared to HPV16 negative patients.(6-9) Our study also compared HPV16 positive and negative patients by race and found that both black and white HPV16 positive patients had a significantly improved overall survival compared to their respective HPV16 negative racial counterparts. There was no difference in overall survival between HPV16 positive black and HPV16 positive white patients. Interestingly, HPV16 negative blacks had a significantly worse overall survival compared to HPV16 negative white patients. The reasons for this disparity are not defined.

Worsham et al compared survival by HPV status and race in 121 OPSCC patients.(13) While they similarly found that HPV positive patients had a significantly improved overall survival compared to HPV negative in their entire cohort and amongst blacks, in contrast they found no difference in overall survival between HPV positive and negative white patients. While whites had a higher percentage of HPV positive tumors, reasons for the lack of impact of HPV status on survival amongst whites in this study are unclear. Similar to our findings there was no difference between black and white HPV positive patients and black HPV negative patients had a significantly shorter survival compared to white HPV negative patients. (13) However, other studies have shown no difference in overall survival between HPV negative white and black patients.(11, 27) This includes our previous analysis of the TAX 324 trial which showed no difference in survival between white HPV negative patients and all black patients, where all but one of the black patients were HPV negative patients.(11)

While there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between HPV16 negative black and white patients in our population (younger age, male predominance, and higher proportion of smokers and drinkers amongst black patients), race was still significantly associated with worse survival amongst HPV negative patients after controlling for these factors as well as TNM stage. In a parallel analysis, we looked at survival by race in more than 500 black and white patients with stage III and IV tumors of the larynx, hypopharynx and oral cavity treated during the same time period at our institution and saw no difference in survival by race for those anatomic sites (data not shown). This suggests that in our population, currently undefined biological differences may be contributing to the worse outcomes seen in HPV16 negative black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Further analysis is needed in order better characterize reasons for disparities in overall survival between HPV negative oropharyngeal cancer patients by race.

Black race was associated with a significantly worse overall survival amongst our entire cohort with tissue available for HPV testing. Given that HPV negative white patients had improved overall survival compared to blacks, in order to evaluate the effects of race and HPV status on overall survival in our patient population we carried out a multivariate analysis. While both race and HPV were independently associated with survival, given the magnitude of the improved prognosis in HPV associated OPSCC seen in our population, and the lack of difference in survival between white and black HPV positive patients, it is more likely that the higher incidence of HPV positive OPSCC amongst white patients, rather than race alone, accounts for their significantly improved overall survival compared to black patients in our entire cohort.

Our paper has a number of potential limitations. While our population was diverse our absolute number of HPV positive black patients was low, albeit similar to other comparisons in the literature.(10, 13) Additionally, changes in proportions of HPV positive OPSCC for both whites and blacks are effected by changes in the incidence of OPSCC. Thus a limitation of our retrospective study is that we cannot determine incidence rates for our population. Another potential limitation is that since testing was confined to HPV16, cases involving other HPV types would have been missed. However, HPV16 accounts for the majority of HPV types worldwide(17). Additionally, because of a low number of HPV16 positive black patients we carried out our linear array analysis on specimens from 27 black patients that were negative for HPV16 by PCR, and found only 1 specimen positive for another HPV type.

Our retrospective analysis of oropharyngeal cancer patients diagnosed from 1992 to 2007 shows a significantly higher percentage of HPV16 positive tumors amongst whites compared to blacks for the entire population as well as over each four year time period examined. Trends for an increase in HPV16 positive OPSCC over time were seen not only in white patients but also in blacks, and we observed the emergence of HPV16 positive OPSCC in black patients treated at UMGCC during the time period examined. HPV16 positive OPSCC was associated with a significantly improved overall survival for both races and amongst HPV16 negative patients black race was associated with a worse outcome even after controlling for selected baseline characteristics. Our analysis highlights the need for further research to better explain the poor prognosis seen in HPV16 negative blacks and the consistent disparity in the prevalence of HPV positive oropharyngeal cancer between black and white patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

None

Funding Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Orakawa foundation

Kevin Cullen receives NIH grant funding (1 P30 CA 134274-01). Dan Zandberg receives NIH grant funding (K12 CA126849)

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have nothing to disclose

Works Cited

- 1.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(9):709–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. Epub 2000/05/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(19):1944–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. Epub 2007/05/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(32):4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. Epub 2011/10/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begum S, Westra WH. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a mixed variant that can be further resolved by HPV status. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2008;32(7):1044–50. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816380ec. Epub 2008/05/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafkamp HC, Manni JJ, Haesevoets A, Voogd AC, Schepers M, Bot FJ, et al. Marked differences in survival rate between smokers and nonsmokers with HPV 16-associated tonsillar carcinomas. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2008;122(12):2656–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23458. Epub 2008/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. Epub 2010/06/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zandberg DP, Bhargava R, Badin S, Cullen KJ. The role of human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63(1):57–81. doi: 10.3322/caac.21167. Epub 2012/12/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R, Fox SB, Le QT, Peters LJ, et al. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(27):4142–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2904. Epub 2010/08/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posner MR, Lorch JH, Goloubeva O, Tan M, Schumaker LM, Sarlis NJ, et al. Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: a subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2011;22(5):1071–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr006. Epub 2011/02/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernock RD, Zhang Q, El-Mofty SK, Thorstad WL, Lewis JS., Jr Human papillomavirus-related squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a comparative study in whites and African Americans. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2011;137(2):163–9. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.246. Epub 2011/02/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, Tan M, Suntharalingam M, Goloubeva O, et al. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer prevention research. 2009;2(9):776–81. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0149. Epub 2009/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XI, Thomas J, Zhang S. Changing trends in human papillomavirus-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Annals of diagnostic pathology. 2012;16(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2011.07.003. Epub 2011/10/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Worsham MJ, Stephen JK, Chen KM, Mahan M, Schweitzer V, Havard S, et al. Improved Survival with HPV among African Americans with Oropharyngeal Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3003. Epub 2013/03/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole L, Polfus L, Peters ES. Examining the incidence of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancers by race and ethnicity in the U.S., 1995-2005. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e32657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032657. Epub 2012/03/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(4):612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. Epub 2008/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. a.

- 17.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14(2):467–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. Epub 2005/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(6):407–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. Epub 2008/03/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(4):261–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. Epub 2008/02/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansson BG, Rosenquist K, Antonsson A, Wennerberg J, Schildt EB, Bladstrom A, et al. Strong association between infection with human papillomavirus and oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2005;125(12):1337–44. doi: 10.1080/00016480510043945. Epub 2005/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. Epub 2010/11/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner CF, Danella RD, Rogers SM. Sexual behavior in the United States 1930-1990: trends and methodological problems. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1995;22(3):173–90. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199505000-00009. Epub 1995/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gates GJ, Sonenstein FL. Heterosexual genital sexual activity among adolescent males: 1988 and 1995. Family planning perspectives. 2000;32(6):295–7. 304. Epub 2001/01/04. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brawley OW. Oropharyngeal cancer, race, and the human papillomavirus. Cancer prevention research. 2009;2(9):769–72. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0150. Epub 2009/07/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Souza G, Cullen K, Bowie J, Thorpe R, Fakhry C. Differences in oral sexual behaviors by gender, age, and race explain observed differences in prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086023. Epub 2014/01/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, Kahle L, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(7):693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. Epub 2012/01/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberger PM, Merkley MA, Khichi SS, Lee JR, Psyrri A, Jackson LL, et al. Human papillomavirus-active head and neck cancer and ethnic health disparities. The Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1531–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.20984. Epub 2010/06/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, Kowalski D, Harigopal M, Brandsma J, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus--associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(5):736–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. Epub 2006/01/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Kountourakis P, Sasaki C, Haffty BG, Kowalski D, et al. Defining molecular phenotypes of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: validation of three-class hypothesis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2009;141(3):382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.04.014. Epub 2009/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.