Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the association between depressive symptoms and several psychosocial constructs (insight into autism symptoms, rumination, desire for social interaction, and satisfaction with social support) that may play a role in the development or maintenance of depression in verbally fluent adolescents and adults with ASD. Participants included 50 individuals with ASD and verbal IQ >= 70, aged 16-35 (sample size varied by measure). Elevated depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition, were associated with greater self-perceived autism-related impairments (n=48), greater rumination (n=21), and lower perceived social support (n=37). Rumination tended to moderate the association between self-perceived autism symptoms and BDI-II scores (n=21), and was significantly associated with ASD-related Insistence on Sameness behaviors (n=18). An unexpected relationship between depressive features and social participation and motivation will need to be clarified by longitudinal research. These and similar findings contribute to our understanding of the phenomenology of depression in ASD, which is critical to the development of practical prevention and treatment.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, depression, rumination, insight, social motivation, social support

Introduction

Clinic-based and community studies suggest that mood disorders are common across the lifespan in individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (Mazefsky, Conner, & Oswald, 2010; Leyfer et al., 2006; Kim, Szatmari, Bryson, Streiner, & Wilson, 2000). For example, in a Swedish sample of 54 adults with Asperger syndrome, 70% had experienced at least one episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) and 50% qualified for recurrent MDD when diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First & Gibbon, 2004) (Lugnegard, Hallerback, & Gillberg, 2011). In a North American study of 627 clinic-based ASD cases, over half the sample currently were rated as “depressed” by parent report, including 72% of cognitively able adolescents (Mayes, Calhoun, Murray, & Zahid, 2011). This comorbidity has been linked to multiple medication usage (Gerhard, Chavez, Olfsun, & Crystal, 2009) and clinical impairment/ functional burden in the focal population as well as their caregivers (Mazefsky et al., 2010; Joshi et al, 2012; Cadman et al., 2012).

Many studies have replicated the existence of a large subgroup within the autism spectrum that has an elevated rate of familial mood disorders (documented prior to the birth of a child with ASD), suggesting the two types of disorders may be related clinically and genetically (DeLong, 2004; Bolton, Pickles, Murphy, & Rutter, 1998; Piven & Palmer, 1999). Beyond a potential genetic relationship, the high comorbidity of depression observed in ASD also is reasonable from a psychosocial perspective. Loneliness and lack of social connectedness have been shown to predict depression in typically developing populations (Williams & Galliher, 2006; Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006). ASD significantly impedes an individual's ability to negotiate reciprocal social interactions (Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004; Lord et al., 2000) and is associated with elevated rates of loneliness (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; White & Roberson-Nay, 2009; Lasgaard et al., 2010), bullying (Shtayermman, 2007), and self-perception of low peer approval and high social incompetence (Meyer, Mundy, Van Hecke, & Durocher, 2006; Hedley & Young, 2006; Williamson, Craig, & Slinger, 2008). Recent evidence specifically links poor social functioning or friendship quality and depressive symptoms within children and adolescents with ASD (Pouw, Rieffe, Stockmann, & Gadow, 2013; Whitehouse, Durkin, Jaquet, & Ziatas, 2009). In general, however, very little has been published on potential psychosocial mechanisms underlying depression in ASD despite the prevalence and clinical significance of this comorbidity.

Insight into social deficits

Depressive symptoms are assessed most often via self-report, and thus depression is more easily identified in individuals with ASD who have intact or minimally-impaired cognitive and verbal abilities. A complementary hypothesis is that these “more able” individuals also may be more likely to experience depression than others with ASD, due to greater awareness of their social deficits and greater desire for social connection (Ghaziuddin et al., 2002). As an analogue, studies of individuals with schizophrenia have found that greater insight into one's diagnosis and impairments is related to higher rates of depression (Mutsatsa et al., 2006). In 22 school-aged children with ASD, higher chronological age and IQ were associated with higher levels of insight into social skill impairments, and low self-perceived social competence was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Vickerstaff, Heriot, Wong, Lopes, & Dossetor, 2007). Similarly, Hedley and Young (2006) found that adolescents with Asperger syndrome who rated themselves as “more different” than others also exhibited greater depressive symptomatology. In 33 adolescents with Asperger syndrome, Barnhill (2001) observed that the more participants attributed social failure to their own ability and effort, the greater depressive symptomatology they expressed. Overall, it is not clear whether individuals with greater verbal and cognitive skills and/or milder ASD symptoms are simply more easily identified with co-occurring depression, are in fact particularly affected, or both (Cederlund, Hagberg, & Gillberg, 2009; Hurtig et al., 2009; see also Gotham, Unruh, & Lord, in review, and Magnuson & Constantino, 2011, for a broader discussion of characterization of depression in ASD). However, perceiving oneself as having social deficits appears to be related to both greater cognitive/verbal abilities and to depressive symptoms. This prompted us to question whether depressive symptoms also would be related to low perceived social support and/or to a disparity between social motivation and actual opportunities for social participation (see also Whitehouse et al., 2009; Pouw et al., 2013).

Rumination in depression and ASD

Rumination is another mechanism indicated in the cause or maintenance of depression in the general population (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Rumination is defined as a pattern of responding to distress with passive and perseverative thinking (e.g., about the cause, consequences, or symptoms related to that distress), while failing to initiate the active problem-solving that might lessen the distress overall (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). In otherwise typically developing adults, rumination has been shown to predict the number and duration of major depressive episodes prospectively (Robinson & Alloy, 2003) and is also highly associated with anxiety (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). In the ASD field, there is a burgeoning interest in the relation between anxiety and the repetitive interests and behaviors that are a primary feature of the autism spectrum (Gotham et al., 2012; Rodgers, Glod, Connolly, & McConachie, 2012; Spiker, Lin, Van Dyke, & Wood, 2012). These repetitive behaviors, such as Insistence on Sameness (see Gotham et al., 2012), are perseverative by very definition; as rumination also is linked to anxiety, depression, and perseveration, it is another particularly important candidate mechanism in studies of depression in ASD. Though it has received minimal research attention to this point, rumination was found to be more prevalent in a sample of adults with ASD (n=28) compared to typical controls (Crane, Goddard, & Pring, 2013), and to be significantly associated with Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, & Mendelson, 1961) scores in that sample.

The present study: Psychosocial pathways to depression in ASD

The purpose of this study is to examine psychosocial mechanisms that may influence the development of depression in verbally fluent adolescents and adults with ASD. By focusing on “depressive symptoms” as an outcome variable, rather than clinical diagnoses of depressive disorders, we maximize power and are able to generalize findings to subthreshold cases who suffer true impairment (Lewinsohn, Solomon, Seeley, & Zeiss, 2000). We hypothesize that depressive symptoms will be higher in participants with (a) greater insight into their own ASD symptoms; (b) higher levels of rumination; (c) a profile in which social motivation is greater than social participation; and (d) low satisfaction with perceived social support. We also test whether the relationship between participants' perception of their own autism-related impairments and depressive symptoms is moderated by level of rumination.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from a sample of 50 adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Inclusion criteria were (1) chronological age between 16 years, 0 months and 35 years, 11 months, (2) a verbal IQ of 70 or greater, (3) reading comprehension at the fifth-grade level or above, (4) a clinical diagnosis of an ASD, including Autistic Disorder (i.e., autism), Asperger syndrome, or Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and (5) participation of a parent/caregiver who was familiar with the focal participant as a young child. Exclusion criteria included significant sensory or motor impairment (e.g., blindness, severe cerebral palsy) that would preclude completion of the standard assessment battery, as well as acute psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). An age ceiling was employed because little is known about the lives of older adults with ASD, and we did not want to confound the study of our explicit hypotheses by including a group of people possibly affected by different stressors and potential mechanisms underlying depression.

Two subsets of participants contributed data: 29 individuals (58% of the sample) were seen as part of an ongoing longitudinal study of consecutive ASD referrals at age 2 (Lord et al., 2006) who were now16-22 years old at the time of this data collection. Because of the practical difficulties of combining lengthy study protocols, a number of these longitudinal study participants received some but not all of the current measures of interest. An additional 21 families were recruited specifically for this study, via current or previous participation with the University of Michigan Autism and Communication Disorders Center (UMACC) or public recruitment for this project, including flyers and presentations at ASD resource centers or job-coaching groups in the southern Michigan area. The Ruminative Response Scale was available only for the 21 participants collected in Michigan (Chronological Age M=23.3 years, SD=4.9 years; Verbal IQ M=106, SD=18.1; 86% Caucasian; 14% Female). See Table 1 for more information on sample size per measure.

Table 1. Sample Description.

| N | Range | Mean(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | 50 | 16-31 | 20.7 (3.9) |

| VIQ | 50 | 72-140 | 105.0 (17.7) |

| NVIQ | 49 | 73-138 | 101.0 (15.8) |

| ADI IS Ever | 41 | 0-11 | 5.8 (2.7) |

| ADI IS Current | 42 | 0-10 | 3.7 (2.2) |

| ADOS Comm-Soc | 35 | 3-18 | 9.5 (3.2) |

| VABCST | 49 | 28-104 | 72.0 (13.8) |

| Proband BPI | 48 | 37-77 | 55.8 (8.5) |

| Examiner BPI | 40 | 36-78 | 59.8 (10.3) |

| SIH-Current | 47 | 2-15 | 8.4 (3.2) |

| SIH-Wishes | 47 | 5-17 | 12.2 (2.9) |

| RRS Total | 21 | 29-70 | 47.1 (14.3) |

| SSQ Total | 37 | 12-36 | 30.5 (5.4) |

| BDI-II | 50 | 0-28 | 9.9 (8.2) |

Note. VIQ=Verbal IQ; NVIQ=Nonverbal IQ; ADI IS Ever=Insistence on Sameness Raw Total based on Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised ‘Ever’ scores; ADI IS Current=Insistence on Sameness Raw Total based on ADI-R ‘Current’ scores; ADOS Comm-Soc=ADOS Communication+Reciprocal Social Combined Total (Module 4); VABCST=Vineland II Overall Adaptive Behavior Composite standard score; Proband BPI=Total on 23 usable items from Proband-rated Behavioral Perception Inventory (maximum total=92); Examiner BPI=Total on 23 usable items from Examiner-rated Behavioral Perception Inventory (maximum total=92); SIH-Current=Total from 7 usable items from the Social Interests and Habits Questionnaire, Social Current Participation form (maximum total=28); SIH-Wishes=Total from 7 usable items from the Social Interests and Habits Questionnaire, Social Wishes form (maximum total=28); RRS Total=Ruminative Response Scale total score; SSQ Total=Sarason Social Support Questionnaire total score; BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory-II total.

All participants ranged in age from 16 to 31 years old (M=20.7 years, SD=3.9). Females comprised 10% of the sample (n=5). Race and ethnicity of the sample was 82% Caucasian (n=41), 12% African American (n=6), and one person (2%) each from the Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, and ‘two or more racial affiliations’ categories. The majority of the sample (73%) lived at home with one or both parents, 12% lived in university housing, 5% lived on their own with significant professional assistance, 4% lived on their own with relative or complete independence, and 7% did not provide information about their living situation. Participant education varied: 31% of the sample was currently in high school receiving significant services, 27% was in high school with minimal to no special education services, 32% had attempted or was currently in college, 3% had completed a college degree, and 7% did not answer. Maternal education ranged from 32% with graduate education, 24% with Bachelor's degrees, 34% with some college, and 4% high school graduates, with data not provided for three participants.

Best estimate clinical diagnoses of autistic disorder, based on clinical judgment informed by diagnostic measures referenced later, were assigned to 29 individuals (58%), PDD-NOS diagnoses were made in 17 participants (34%), and 4 (8%) had Asperger syndrome. See Gotham et al. (in press) for data on co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders in this sample and their relation to several parent- and self-report depression measures.

Procedures

The data collection protocol included a packet of questionnaires and a face-to-face assessment for both the adolescent or adult participant with ASD (i.e., proband) and his/her parent. Data were collected and clinical diagnoses assigned by advanced graduate students and research assistants, all of whom had undergone extensive training to achieve research reliability on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Rutter, LeCouteur, & Lord, 2003); this took place under the supervision of licensed clinical psychologists. All relevant clinicians/examiners discussed the case and came to a consensus agreement about clinical diagnoses based on all available information. Questionable cases were reviewed by the authors C.L., S.B., and K.G. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board in Health and Behavioral Sciences approved all procedures related to this study.

Measures

Measures related to the current hypotheses, the outcome variable, and those used to ascertain ASD diagnosis are discussed below. Note that several other self- and parent-report questionnaires and interviews of depressive symptoms were administered in this sample to support categorical diagnosis of mood disorders and in order to compare the utility of common measures of depression in ASD (see Gotham et al., in press).

Parent measures

A face-to-face visit with parent participants included the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Rutter, LeCouteur, & Lord, 2003) in order to confirm ASD diagnosis, and the second edition of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) to assess proband adaptive functioning.

Proband measures

The standard battery for participants with ASD included a mailed packet of self-report questionnaires pertaining to demographics and psychological health, and a face-to-face assessment in which probands completed the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999); the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability (Neale, 1997) or the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT; Wilkinson & Robertson, 2006) reading comprehension subtests in order to verify reading comprehension necessary to complete questionnaires; the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000) for adolescents and adults with fluent speech; the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II; Beck, 1996; see also Gotham et al., in press, for details on this measure and its use in this sample); the Ruminative Response Scale of the Response Styles Questionnaire (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991); and the Sarason Social Support Questionnaire, Short Form (SSQ; Sarason, Sarason, Shearin, & Pierce, 1987). The RRS is a 22-item self-report questionnaire assessing ruminative responses to depressed mood on a four-point scale. This measure was found to have excellent intraclass correlation and strong test-retest correlation in a large typically developing sample (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003); it had excellent intraclass correlation (ICC) of .94 in the current sample (n=21). Though it has not been validated for use in the ASD population, see Crane et al. (2013) for comparison descriptives of RRS scores in an ASD sample. The SSQ Short Form measures self-perceived availability of social support as well as satisfaction with perceived available support using a 6-point Likert scale. Considerable evidence has accumulated attesting to the construct and discriminant validity of the 27-item SSQ in the general population (see Sarason et al., 1991), though we found no validation evidence for this short form or any other measure of social support within ASD. The satisfaction ratings of the SSQ short form used in these analyses below had an ICC of .88.

Behavioral Perception Inventory (BPI)

In addition to the instruments above, participants completed two new measures created specifically to assess constructs relevant to the current study. The first is the Behavioral Perception Inventory (BPI; available upon request from the first author; see also Supplementary Table for item content), on which both participants and clinician/examiners independently rated to what degree each of 23 autism-related behaviors described the participant's behavior (e.g., Do you forget to give people a turn to talk when you are excited about a topic?; Do you feel more comfortable when things happen the same way every time?). Responses were on a four-point Likert scale (Almost Never, A Little, Pretty Much, Almost Always), and the Proband version contained a validity scale and additional positive “filler” items. The BPI was created in order to operationalize self-perception of ASD symptoms (i.e., Proband total scores) with an internal control for actual level of symptomatology using the same item set (i.e., Examiner totals were used as a proxy for “true” scores). Examiner BPI was rated based on all available information, which necessarily included direct interaction with the participant during the ADOS and cognitive testing. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were acceptable to good (ICC=.80 for the Proband version and .73 for the Examiner version), indicating adequate internal consistency of the new measure.

Social Interests and Habits Questionnaire

The second novel measure was the Social Interests and Habits Questionnaire (SIH; available from first or second authors), which assesses participants' wish for involvement in several social domains as well as their current degree of involvement. The “Social Current” section (SIH-SC) includes 7 questions about social participatory behaviors (e.g., How often do you email or chat online with friends?) rated on a four-point likert scale (None, A Little, Pretty Much, A Lot). The “Social Wishes” section (SIH-SW) includes 7 Likert-rated questions about the proband's desire to engage in the same social participatory behaviors assessed in the Social Current scale. Despite the small number of items, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were fair to acceptable (ICC=.71 for the Social Current and .63 for Social Wishes) when the intentionally contrasting items (i.e., those pertaining to time spent at home alone or with family rather than friend-based social activity) were dropped from reliability analysis.

The proband battery was structured to avoid bias or contamination of responses. The SIH was counter-balanced such that a randomly determined half of participants rated their desired amount of social experiences (SIH-SW) before answering questions about their actual amount of current social contact (SIH-SC), with the other half of participants receiving the ‘current’ questions before the ‘desired’ questions; no significant order effects were observed in the resulting data. The BDI-II was administered directly following the cognitive test, before the ADOS, BPI, or measures of social experiences and support, in order to eliminate a priming effect of potentially negative topics.

Design and analyses

In light of findings that Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II; Beck, 1996) scores in ASD samples are associated with categorical diagnoses of depression and are minimally associated with participant age and IQ (Cederlund et al., 2009; Gotham et al., in press), the BDI-II serves as the outcome measure in this study. To address all primary hypotheses, variables of interest were centered at the sample mean and entered into multiple linear regression models, along with centered chronological age, as predictors of BDI-II scores. To assess moderator effects, main effects and interaction terms were modeled. Because of the sample size, only 3 or fewer parameters could be estimated per model (Harrell, 2001).

Proband BPI scores operationalized self-perception of autism-related syptoms or impairment. The interaction between Proband and Examiner BPI scores was intended to operationalize insight (i.e., self-perception that agrees with expert ratings) as a related but distinct construct. However, this interaction could not be assessed as a predictor of BDI-II scores due to multicollinearity between raters' BPI totals. Thus, exploratory methods based on Principal Component Analyses were used to make inferences about the effects of Examiner-Proband agreement on the BPI, as well as to explore particular symptom groupings in which differing levels of insight might influence depression scores.

Due to interest in rumination as a potential link between depression and the perseverative focus observed in ASD, centered Ruminative Response Scale, age, and VIQ also were entered as predictors of ADI-R Insistence on Sameness (IS) raw totals. IS raw totals were created by summing those ADI-R items previously observed to load on an IS factor in a large ASD sample (see Gotham et al., 2012, for method of deriving IS factor). To test the hypotheses that a disparity between social interest and social participation would be associated with higher depressive symptoms, actual social participation (Social Current) and desired social participation (Social Wishes) totals were generated by summing all SIH items related to current and desired social participation, respectively, with the exclusion of the item on each form that pertains to engaging in a hobby at home (which could be solitary); main effects and interaction of Social Current and Social Wishes totals were modeled as predictors of BDI-II scores.

Because of increased Type II error associated with a relatively small sample size, as well as the fact that we were testing specific theory-based hypotheses, we did not apply a more stringent criterion-standard (e.g., a corrected p-value) but rather report effect sizes and encourage replication of this work in larger samples. We report the unstandardized beta coefficient (b) with a 95% confidence interval, the squared semi-partial correlation coefficient (sr2), which represents the percentage of the total variability in the outcome that is uniquely accounted for by the predictor of interest, and Cohen's f2, which is the ratio of sr2 to the total amount of unexplained variance: sr2/(1 − R2). Conventional thresholds for “small,” “medium,” and “large” f2 values are 0.02, 0.15, 0.35, respectively (Cohen, 1992).

Results

Hypothesis 1: Depressive symptoms will be higher in participants with greater insight into their own ASD symptoms

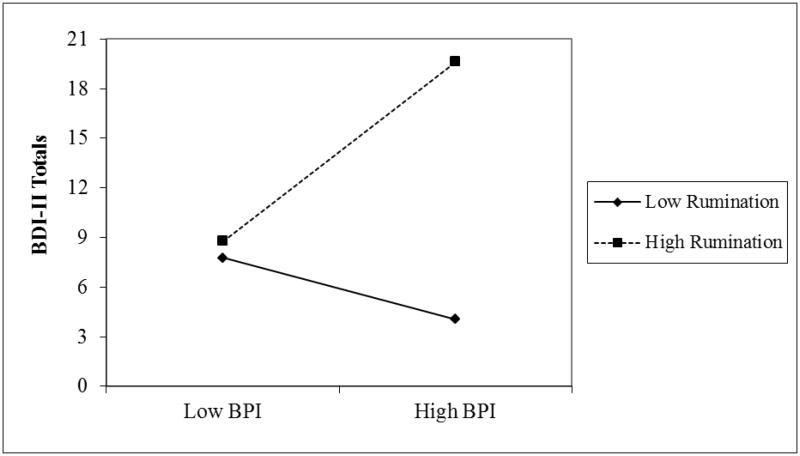

Proband-rated BPI totals significantly predicted BDI-II scores (b = 0.442 [0.163, 0.721], sr2 = .207, f2 = .304) when controlling for mean-centered Examiner BPI totals (as a proxy for actual level of impairment) and chronological age. This finding indicates that higher levels of self-perceived autism-related impairment were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms on the BDI-II, controlling for clinician-rated impairment. Figure 1 depicts the positive relationship between increasing depressive symptoms and Proband BPI totals (r=.52; large effect size [see Cohen, 1992]) compared to Examiner BPI totals (r=.20; small effect size). All analyses that include Examiner BPI were based on n=40 participants, after excluding cases in which examiners were missing 4 or more BPI item ratings; missing data were associated with a response option indicating that the examiner did not have enough information to rate that particular item.

Figure 1. Beck Depression Inventory Scores by Proband and Examiner Behavioral Perception Inventory Ratings.

Exploratory analyses of insight

We used exploratory methods to assess whether perceived impairment alone and/or insight (self-perception that generally agrees with an expert rating) were related to depressive symptoms differentially for certain types of ASD symptoms, e.g., awareness of social impairments versus repetitive behavior. Examiner-minus-Proband item-level difference scores were used to operationalize insight into true symptom levels. When entered in a principal components analysis (PCA) with promax rotation, item difference scores were best described by three components that explained 44% of the variance (see Supplementary Table at [website] for items, factor loadings, and summary statistics): Insight into Conversational Skill, Compulsive/Ritualized Behavior, and Functional Independence. Three similar components were observed in a PCA of Proband item scores that were not adjusted for Examiner scores. Of the three components in each set, only the “Functional Independence” factors were significantly associated with BDI-II scores, with a stronger effect in the perceived impairment versus insight model: b = -2.750 [-5.380, -0.121], sr2 = .099, f2 = .115 for Proband-Examiner difference scores (n=40) (versus sr2 = .019, f2 = .021 for Conversational insight and sr2 = .026, f2 = .029 for Compulsive/Ritualized insight), and b = 3.881 [1.834, 5.927], sr2 = .205, f2 = .333 for Proband unadjusted scores (n=48) (versus sr2 = .052, f2 = .078 for Conversational self-perception and sr2=.020, f2 = .032 for Compulsive/Ritualized self-perception). This finding was relatively robust (b = 3.561 [0.006, 7.116], sr2 = .076, f2 = .108) to models controlling for centered Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Composite standard scores (VABC), suggesting that the degree of adaptive impairment itself did not account for the association between depressive symptoms and perceived functional impairment. Note that, in the PCA from which these components were derived, communalities and item-to-subject ratio were quite low (see Supplementary Table note), possibly indicating an underpowered analysis with results that may be specific to the current small sample.

Hypothesis 2: Depressive symptoms will be higher in participants with higher levels of rumination

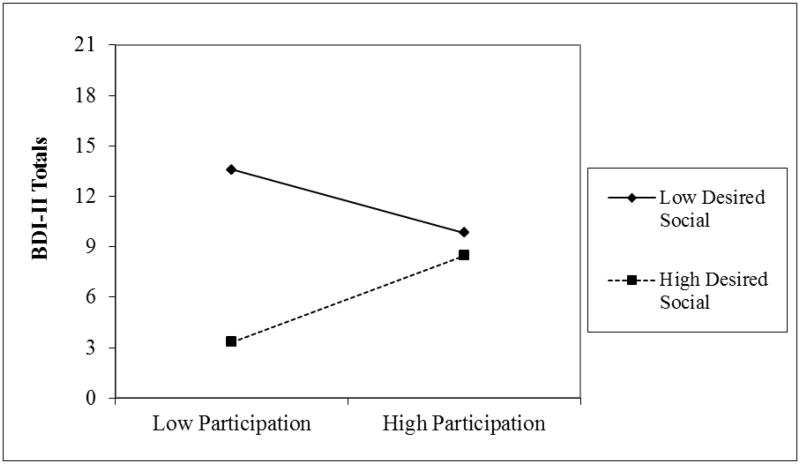

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) totals were strongly and positively associated with BDI-II scores, controlling for age and verbal IQ (b = 0.400 [0.164, 0.636], sr2 = .402, f2 = .751; n=21). We also assessed rumination as a moderator of the relationship between perceived autism impairment and depressive symptoms in the small subsample with RRS data. The interaction of RRS Total and Proband BPI approached significance, with a medium effect size (b = 0.034 [-0.005, 0.072], sr2 = .088, f2 = .197) as a predictor of BDI-II scores, again with a significant main effect of RRS Total (b = 0.288 [0.021, 0.556], sr2 = .136, f2 = .305). In other words, among those with high levels of rumination there was a significant positive relationship between perceived ASD impairment and depressive symptoms, in contrast to minimal relation between perceived ASD impairment and depressive symptoms at low levels of rumination (see Figure 2). A “regions of significance” test (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006) indicated that the slope associated with the regression of depressive symptoms on perceived impairment was significant when rumination scores were approximately 1 SD or higher above the sample mean.

Figure 2. Interaction trend between rumination and perceived autism symptomatology.

Note. Low BPI=Lower Proband total on Behavioral Perception Inventory (i.e., low perceived autism-related symptomatology)

High BPI=Higher Proband total on Behavioral Perception Inventory (i.e., high perceived autism-related symptomatology)

Low Rumination=Lower totals on the Ruminative Response Scale

High Rumination=Higher totals on the Ruminative Response Scale

To explore rumination as a potential link between depression and the perseverative focus observed in ASD, centered RRS, age, and VIQ were also entered as predictors of Insistence on Sameness (IS) raw totals. In a small subset with all available data (n=18), both chronological age and RRS total approached significance as predictors of IS scores after controlling for verbal IQ (Age: b = -0.295 [-0.629, 0.038], sr2 = .189, f2 = .388; RRS: b = 0.102 [-0.006, 0.209], sr2 = .216, f2 = .443). Though associated with BDI-II and IS totals (BDI-RRS: r=.66, p=.001, n=21; IS-RRS: r=.55, p=.04; n=18), RRS scores appear to be measuring something unique rather than pure overlap with either depressive symptoms or insistence on sameness in this ASD sample.

Hypothesis 3: Depressive symptoms will be higher in participants with a profile in which social motivation is greater than social participation

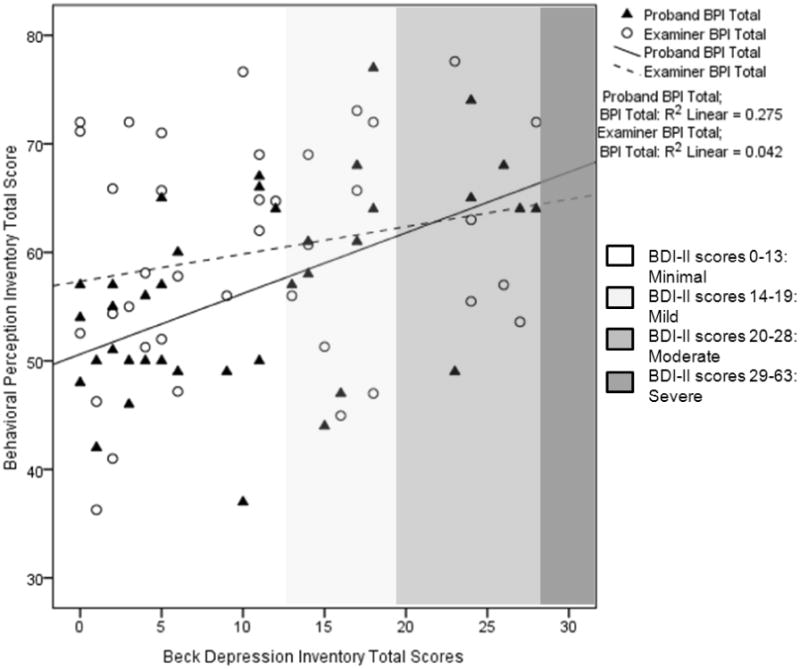

The interaction between summed ratings of actual current social participation and desired social participation was not significantly associated with BDI-II scores. Further, we observed a significant main effect of desired social participation in the direction opposite our expectations: lower ratings of desire for social interaction were associated with higher ratings of depressive symptoms on the BDI-II (b = -1.053 [-2.102, -0.005], sr2 = .080, f2 = .096; n=47). The group that tended toward the lowest BDI-II scores was the same group we postulated would have the highest: those with high motivation for social interaction and low actual participation (see Figure 3). Of note, the group with the highest depression ratings tended to report both low social participation and low social motivation.

Figure 3. Interaction trend between desired and actual social participation.

Note. Data based on the Social Interests and Habits Questionnaire (SIH).

Participation=Data on current social participation from SIH, Social Current Form.

Desired Social=Data from SIH, Social Wishes Form.

Hypothesis 4: Depressive symptoms will be higher in participants with low satisfaction with perceived social support

Totals on the centered Sarason Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) were significantly associated with BDI-II totals (b = -0.538 [-1.065, -0.011], sr2 = .107, f2 = .131; n=37) in the expected direction (i.e., lower satisfaction with social support was associated with higher depressive ratings), controlling for chronological age and verbal IQ.

Discussion

Perceived ASD impairment

The aims of this study were to examine the association between depressive symptoms and several psychosocial constructs (insight into autism symptoms, rumination, desire for social interaction, and satisfaction with social support) that may elucidate mechanisms in the development or maintenance of depression in adolescents and adults with More Able ASD. We found that participants' perceptions of their own autism-related impairment were positively associated with their depressive symptoms, regardless of their “true” degree of impairment (i.e., examiners' perceptions of their autism-related symptoms on the same scale). This echoes the findings of Vickerstaff et al. (2007) that school-aged children's perceived social competence was negatively associated with depressive symptoms regardless of whether these participants with ASD were rated by parents and teachers as socially competent compared to peers. Similarly, Williamson and colleagues found that adolescents (N=19) with Asperger's syndrome who perceived themselves to be less socially competent and to receive less peer approval than typical controls had lower ratings of global self-worth (Williamson et al., 2008).

Taken together, these findings suggest that self-esteem may be an important moderator of depressive symptoms in ASD. This is consistent with cognitive theories of depression from the general population (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979); depressed individuals tend to process information about themselves in a more negative way than their non-depressed counterparts (Golin, Terrell, Weitz, & Drost, 1979). Evidence that negative attributions function similarly in ASD and the general population – that is, as a form of cognitive vulnerability that is a well-documented pathway to depression (Hankin et al., 2009) – is important for adapting findings from the depression treatment literature to ASD.

Depressed respondents might have been more likely to rate themselves as impaired than were non-depressed participants due to negative attributions, rendering our finding on self-perceived ASD-related symptoms an artifact of depression itself. To highlight a possible alternative, we have included in this paper the exploratory results from principal components analysis of the Behavioral Perception Inventory (these results must be considered within the limits of underpowered analyses and questions of generalizability beyond this sample; nevertheless, exploratory findings can contribute to our understanding of minimally-studied phenomena such as this). If proband perceptions of impairment were a result of depression rather than a potential cause, we would expect a halo effect of negative cognitions, with the depressed group more apt to endorse poor skills or limitations throughout the BPI. Instead, significant association between perceived impairment and depressive scores was limited to the Functional Independence factor alone, an effect which was robust despite a small sample size and even when accounting for effects of adaptive behavior impairments themselves. Symptoms of depression might be a reasonable response to limitations in achieving one's goals and independently caring for oneself, which are common challenges faced by the ASD population across age and IQ levels (Duncan & Bishop, in press). If replicated, this finding may suggest a target for intervention strategies for depression and well-being in ASD.

Rumination

In the current study, perceived autism-related impairments, which may indicate negative self-appraisal, tended to be associated with depressive symptoms largely in the presence of elevated rumination (effect size=.74). Conversely, rumination was most strongly associated with depressive symptoms in the presence of high perceived impairment (see Figure 2). This engenders an intriguing hypothesis for the development and maintenance of depression in ASD, i.e., as the extent to which individuals see themselves as impaired and get “stuck” on those thoughts. Ruminative Response Scale scores for this small sample (M=47.1, SD=14.3) and in a previous adult ASD sample (M=50.11; SD=15.01; Crane et al., 2013) are both, at face value, more similar to published means in depressed adults (e.g., M=48.2; SD=9.4; n=104) versus non-depressed controls (M=40.2, SD=10.3; n=1109) (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Similarly the RRS-BDI correlation of .66 in this sample replicates the Crane et al. (2013) ASD sample (r=.65), compared to r=.48 in Nolen-Hoeksema's (2000) large typically developing sample. Finally, we found an association between rumination and Insistence on Sameness (perseverative preferences that mark the autism phenotype), suggesting that those individuals who are likely to perseverate on routines, rituals, and circumscribed interests also may be more likely to perseverate on psychological substrates. This supports the idea that perseveration in ASD influences emotion regulation in this population (Mazefsky, Pelphrey, & Dahl, 2012). We would do well to investigate whether children with high IS become adolescents and adults who ruminate and become depressed.

Of particular interest, the rumination-IS link could belie mechanisms of depression onset that are neurobiological, psychosocial, or both. In the depression and anxiety fields, rumination generally is considered detrimental because it is a passive coping strategy (but see also Marroquin, Fontes, Scilletta, & Miranda, 2010). Pouw et al. (2013), however, found that higher levels of avoidant coping (which is also passive) were associated with lower levels of depression in their study of 63 high-functioning school-aged boys with ASD. Perseverative thoughts and behavior within ASD often appear to have the quality of a motivating drive rather than a mechanism of avoidance. We do not yet know whether IS-type rumination common to ASD is used as a coping strategy at all, whether it precludes active problem-solving, or generally functions in the same way (with similar neural pathways and cognitive and emotional sequelae) as rumination that is commonly associated with depression. Answering these questions could be key to understanding increased risk for depression in ASD.

Social motivation versus participation

Elevated depressive symptoms were associated with less perceived social support. However, individuals with higher social motivation and lower social participation did not appear to be particularly affected by depressive symptomatology. The group that tended toward the highest BDI-II scores showed a profile of low social motivation and low social participation. For some participants, depression likely was the causal factor in this profile instead of the reverse, as social anhedonia and amotivation are common symptoms of depression. Thus our hypothesis could not be tested fully due to the absence of social motivation data that pre-dated onset (or increase) of depressive symptoms. This hypothesis would be better explored with a trait-based measure of social motivation and participation, as well as prospective assessment of social interest prior to onset of depressive features.

An alternative interpretation of the finding that low social interest and participation was most (though not significantly) associated with depressive symptoms is that individuals described by the “aloof” subtype of ASD (Wing & Gould, 1979) may be at particular risk for depression. If the findings withstand replication, exploration of those genetic, biological, and psychosocial risk factors is warranted, as is careful thought and study of how to treat depressed individuals who already have dramatically low social motivation at pre-depression baseline.

Limitations

The primary limitations of our study are the small sample size and the need for further validation of these measures in the ASD population. Though the sample size meant that some analyses, particularly with regard to exploratory BPI principal components analysis, were underpowered, rumination and perceived impairment had consistently significant effects on BDI-II scores despite limited power to detect relationships. Because we conducted planned tests on a priori hypotheses and reported effect sizes, we rely on future replication in larger independent samples rather than setting a high criterion standard to correct for number of analyses. Interrater and test-retest reliability have not yet been established for the newly created study measures, the BPI and SIH (see Supplementary Table note for limitations to exploratory analyses). Finally, recruitment bias may exist in this sample, in that community recruitment strategies explicitly referred to this as a study of “well-being” and “emotional health” in ASD. However, less than half the sample represented community recruits.

Conclusions and future directions

We have an important challenge ahead to support positive outcomes in the mental health and social networks of adults with ASD. These findings suggest that ruminating on one's own autism-related impairment may be related to depressive symptoms in verbally fluent adolescents and adults with ASD. This should be tested in longitudinal designs to examine whether cognitive appraisal predicts coping behavior and the development of later depression. Study of other potential psychosocial mechanisms underlying depression in ASD (e.g., reciprocity of friendship) similarly may inform treatment development. Further exploration of the role of rumination in ASD should take neurobiological models into account and investigate parallel processes in perseveration on negative stimuli (rumination) versus positive/neutral stimuli (circumscribed interests/repetitive behavior).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and their families, and Drs. Israel Liberzon, Albert Cain, Mohammed Ghaziuddin, and Brady West. Grant Sponsors: National Institutes of Health; Grant Numbers: T32-MH18921, P30HD15052; R01MH081873-01A1; RC1MH08972; R01HD065277.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Lord receives royalties from the publisher of the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), and Drs. Gotham and Bishop receive royalties from the ADOS-2, the second edition of the measure described here. Drs. Lord, Bishop, and Gotham donate to charity all royalties from clinics and projects in which they are involved. Dr. Brunwasser has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barnhill GP. Social attributions and depression in adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2001;16(1):46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The Friendship Questionnaire (FQ): An investigation of adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:509–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1025879411971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Kasari C. Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development. 2000;71(2):447–456. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Shulman C. The development and maintenance of friendship in high functioning children with autism: Maternal perceptions. Autism. 2003;7(1):81–97. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories–IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton PF, Pickles A, Murphy M, Rutter M. Autism, affective and other psychiatric disorders: Patterns of familial aggregation. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(2):385–395. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadman T, Eklund H, Howley D, Hayward H, Clarke H, Findon J, et al. Glaser K. Caregiver Burden as People With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Transition into Adolescence and Adulthood in the United Kingdom. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederlund M, Hagberg B, Gillberg C. Asperger syndrome in adolescent and young adult males. Interview, self-, and parent assessment of social, emotional, and cognitive problems. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2010;31(2):287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Goddard L, Pring L. Autobiographical memory in adults with autism spectrum disorder: The role of depressed mood, rumination, working memory and theory of mind. Autism. 2013;17(2):205–219. doi: 10.1177/1362361311418690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong R. Autism and familial major mood disorder: Are they related? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2004;16:199–213. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A, Bishop S. Understanding the gap between cognitive abilities and daily living skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders with average intelligence. Autism. doi: 10.1177/1362361313510068. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) In: Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol 2: Personality assessment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2004. pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard T, Chavez B, Olfson M, Crystal S. National patterns in the outpatient pharmacological management of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;29(3):307–310. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a20c8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziuddin M, Alessi N, Greden JF. Life events and depression in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1995;25(5):495–502. doi: 10.1007/BF02178296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziuddin M, Ghaziuddin N, Greden J. Depression in persons with autism: Implications for research and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32(4):299–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1016330802348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin S, Terrell F, Weitz J, Drost PL. The illusion of control among depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88(4):454–457. doi: 10.1037/h0077992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Bishop S, Hus V, Huerta M, Lund S, Buja A, Krieger A, Lord C. Exploring the relationship between anxiety and insistence on sameness in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research. 2012;6(1):33–41. doi: 10.1002/aur.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Unruh K, Lord C. Depression and its measurement in verbally fluent adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. doi: 10.1177/1362361314536625. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, Goldband J. Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1327–1338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Young R. Social comparison processes and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2006;10(2):139–153. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtig T, Kuusikko S, Mattila M, Haapsamo H, Ebeling H, Jussila K, Joskitt L, Pauls D, Moilanen I. Multi-informant reports of psychiatric symptoms among high-functioning adolescents with Asperger syndrome or autism. Autism. 2009;13(6):583–598. doi: 10.1177/1362361309335719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Shyness and low social support as interactive diatheses, with loneliness as mediator: Testing an interpersonal-personality view of vulnerability to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(3):386–394. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Wozniak J, Petty C, Martelon MK, Fried R, Bolfek A, et al. Biederman J. Psychiatric comorbidity and functioning in a clinically referred population of adults with autism spectrum disorders: A comparative study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Szatmari P, Bryson S, Streiner D, Wilson F. The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2000;4(2):117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusikko S, Pollock-Waurman R, Jussila K, Carter A, Mattila M, Ebeling H, Pauls D, Moilanen I. Social anxiety in high-functioning children and adolescents with autism and asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1697–1709. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasgaard M, Nielsen A, Eriksen M, Goossens L. Loneliness and social support in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010:40–2. 218–226. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0851-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Solomon A, Seeley JR, Zeiss A. Clinical implications of “subthreshold” depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000:109–2. 345–351. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.345.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyfer O, Folstein S, Bacalman S, Davis N, Dinh E, Morgan J, Tager-Flusberg H, Lainhart J. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: Interview development and rates of disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36 doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Kennedy JA, Dosa NP. Social participation in a nationally representative sample of older youth and young adults with autism. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2011;32(4):277–283. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31820b49fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore P, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):694–701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugnegård T, Hallerbäck MU, Gillberg C. Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(5):1910–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson KM, Constantino JN. Characterization of depression in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 2011 doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318213f56c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquín BM, Fontes M, Scilletta A, Miranda R. Ruminative subtypes and coping responses: Active and passive pathways to depressive symptoms. Cognition & Emotion. 2010;24(8):1446–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Murray MJ, Zahid J. Variables associated with anxiety and depression in children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2011;23(4):325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Conner CM, Oswald DP. Association between depression and anxiety in high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders and maternal mood symptoms. Autism Research. 2010;3(3):120–127. doi: 10.1002/aur.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Pelphrey KA, Dahl RE. The need for a broader approach to emotion regulation research in autism. Child development perspectives. 2012;6(1):92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern C, Sigman M. Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JA, Mundy PC, van Hecke AV, Durocher JS. Social attribution processes and comorbid psychiatric symptoms in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2006;10(4):383–402. doi: 10.1177/1362361306064435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutsatsa SH, Joyce EM, Hutton SB, Barnes T. Relationship between insight, cognitive function, social function and symptomatology in schizophrenia: The West London first episode study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(6):356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MD. Neale Analysis of Reading Ability – Revised. Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Palmer P. Psychiatric disorder and the broad autism phenotype: evidence from a family study of multiple-incidence autism families. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):557–563. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouw LB, Rieffe C, Stockmann L, Gadow KD. The link between emotion regulation, social functioning, and depression in boys with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7(4):549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Alloy LB. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: a prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J, Glod M, Connolly B, McConachie H. The relationship between anxiety and repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(11):2404–2409. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1531-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C. In: Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised–WPS. WPS, editor. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearing EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1987;4:497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Pierce GR, Shearin EN, Sarason IG, Waltz JA, Poppe L. Perceived social support and working models of self and actual others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(2):273. [Google Scholar]

- Shtayermman O. Peer victimization in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome: A link to depressive symptomatology, anxiety symptomatology and suicidal ideation. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2007;30(3):87–107. doi: 10.1080/01460860701525089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 2nd. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spiker MA, Lin CE, Van Dyke M, Wood JJ. Restricted interests and anxiety in children with autism. Autism. 2012;16(3):306–320. doi: 10.1177/1362361311401763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling L, Dawson G, Estes A, Greenson J. Characteristics associated with presence of depressive symtpoms in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1011–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Barnard L, Pearson J, Hasan R, O'Brien G. Presentation of depression in autism and Asperger syndrome: A review. Autism. 2006;10:103–113. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Vickerstaff S, Heriot S, Wong MG, Lopes A, Dossetor D. Intellectual ability, self-perceived social competence and depressive symptomatology in children with high-functioning Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(9):1647–1664. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Roberson-Nay R. Anxiety, social deficits, and loneliness in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(7):1006–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse AJO, Durkin K, Jaquet E, Ziatas K. Friendship, loneliness and depression in adolescents with Asperger's syndrome. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4, professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KL, Galliher RV. Predicting depression and self-esteem from social connectedness, support, and competence. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:855–874. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson S, Craig J, Slinger R. Exploring the relationship between measures of self-esteem and psychological adjustment among adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2008;12:391–402. doi: 10.1177/1362361308091652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing L. Language, social, and cognitive impairments in autism and severe mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1981;11(1):31–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01531339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.