Abstract

One of the most important issues in bone tissue engineering is the search for new materials and processing techniques to create novel scaffolds with 3-D porous structures. Although many properties such as biodegradability and porosity have been considered in designing bone scaffolds, very limited attention is paid to their capillary effect. In nature, capillary effect is ubiquitously used by plants and animals to constantly transport water and nutrients based on morphological and/or chemical gradient structures at multiple length-scales. In this work, we developed a modified freeze-casting technique to prepare ceramic scaffolds with gradient channel structures. The results show that our hydroxyapatite (HA) scaffolds have interconnected gradient channels that mimic the porous network of natural bone. More importantly, we demonstrate that such a scaffold has a very unique capillary behavior that promotes the self-seeding of cells when in contact with a cell solution due to spontaneous capillary flow generated from gradient channel structures. The strategy developed here provides new avenue for designing “smart” scaffolds with complex porous structures and biological functions that mimic natural tissues.

Keywords: biomimetic, scaffold, bone, cell seeding, freeze-casting, capillary

1. Introduction

Bone is the second most commonly transplanted tissue with 2.2 million bone-grafting procedures performed annually worldwide [1-3]. The regeneration and repair of large bone defects in load-bearing situations continue to be a challenging problem due to the lack of vascularization and mass transport (nutrient exchange) in the interior parts of the implant [4]. As autografting and allografting have significant limitations, such as donor-site morbidity, the possible transmission of diseases, and limited supply, the availability of customized bone grafts engineered in vitro would revolutionize the way we currently treat bone defects [5-7]. In this tissue-engineering approach, one of the most important issues is searching for new materials and processing techniques for creating scaffolds with biocompatibility, biodegradability, mechanical properties for temporary support, and in particular, three-dimensional (3-D) porous structures [8] for cell attachment, drug delivery, and nutrient transport [9]. Beyond all these aspects of designing scaffolds, very limited attention has been paid to the capillary effect of such porous structures. In nature, the capillary effect is ubiquitously used by plants and animals to constantly transport water and nutrients based on morphological and/or chemical gradient structures at multiple length scales [10-12]. For example, bone has complex interconnected networks, such as Haversian and Volkmann’s canals, within its highly anisotropic structure for constant blood supply [13]. In this context, the design of bone scaffolds with carefully controlled architectural characteristics that would promote capillarity, such as porosity, pore shape, and pore size, is challenging [14].

Here, we designed and fabricated novel biomimetic scaffolds by freeze-casting (or ice-templating) a slurry of hydroxyapatite (HA) particles. The as-prepared HA scaffold has interconnected gradient channels that mimic the porous network of natural bone. More importantly, we demonstrated that such a scaffold has a very unique capillary behavior that promotes the self-seeding of cells when in contact with a cell solution due to spontaneous capillary flow generated from gradient channel structures. We describe here novel scaffolds for bone regeneration, and provide a new way for designing “smart” scaffolds with complex porous structures and biological functions that mimic natural tissues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of biomimetic gradient scaffold

Biomimetic gradient scaffolds were prepared by freeze-casting hydroxyapatite slurry (20 vol% ceramic content). The slurry was prepared by mixing distilled water with hydroxyapatite powders (density = 3.15 g/cm3, 20 vol %) (Hydroxyapatite #30, Trans-Tech, Adamstown, MD), 1 wt % of Darvan 811 (R. T. Vanderbilt Co., Norwalk, CT), 1 wt % of Poly (ethyl-glycol) (PEG-300, Sigma-Aldrich), and 2 wt % of an aquazol polymer (ISP) with a molecular weight of 50,000 g/mol. Slurries were ball-milled for more than 20 hours and de-aired in a vacuum desiccator before freeze-casting. The slurries were then poured into a round plastic mold (44.45 mm in diameter), with a thin copper rod (3.175 mm in diameter) at the center (Fig. 1), which is connected to a liquid nitrogen reservoir. During the freezing process, lamellar ice crystals grew preferentially from the copper rod outward to the plastic mold, generating a gradient in their thickness. At the same time, HA particles were expelled and assembled to replicate the structure of ice crystals. Frozen samples were sublimated (−50°C, under 0.035 mbar, Freeze dryer 8, Labconco, Kansas City, MI) for over 48 hours, and sintered at 1,300°C for 2 hours (Air furnace: 1216BL, CM Furnaces Inc., Bloomfield, NJ).

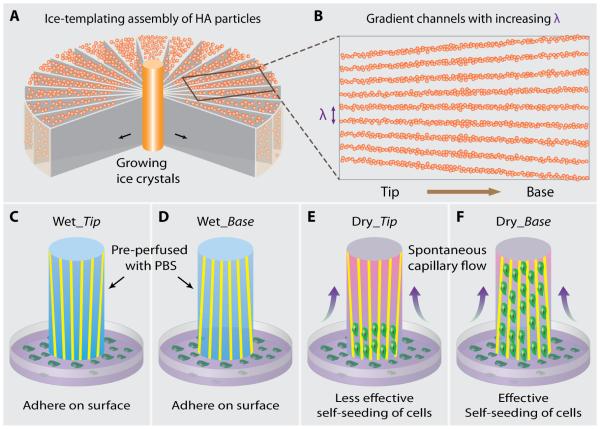

Fig. 1.

Scheme of the fabrication of gradient ceramic scaffold and cell-seeding experiment. (A) When the ceramic slurry is freezing from the cold finger at the center, the growing ice crystals expel the hydroxyapatite (HA) particles and assemble them into a lamellar structure oriented parallel to the freezing direction. Since the ice front is circular, the lamellar spacing becomes wider and wider toward the mold. (B) After sintering, an HA scaffold with increasing channel width (λ) from tip to base side is obtained. In order to study the capillary effect of the gradient channels on seeding cells, (C-D) “wet scaffolds” pre-perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or (E-F) “dry scaffolds” are contacted with cell solution with their tip or base side, Wet_Tip, Wet_Base, Dry_Tip, and Dry_Base, respectively. All the scaffolds had the same size (12 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm). Lacking of capillary effect, cells adhered only to the outer surface of the wet scaffolds, regardless of whether the tip or base side contacted the cell solution. In the case of the dry scaffolds, cells were effectively self-loaded under the capillary. In addition, cells penetrated a much longer distance along the channels when the cell solution contacted the base rather than the tip side.

2.2. Characterization of biomimetic gradient scaffold

The SEM images of the scaffolds were obtained using a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (JSM-5700F, JEOL, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV, after being coated with gold by sputtering at 30 mA for 60 s. To assess the channel width variation along the sample height, SEM images of horizontal cross-sections were taken at multiple locations. Using ImageJ software, channel widths were manually measured on lines perpendicular to the ceramic walls. For each location, more than 100 measurements were performed.

2.3. 3-D reconstructed scaffolds

Synchrotron X-ray tomography experiments were carried out on beamline 8.3.2 at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA). Samples were scanned with a 34 keV monochromatic beam and imaged with a PCO-Edge CCD camera at 2560 × 2160 pixels resolution. A field of view of 3 mm and a voxel size of 1.3 μm were obtained using a 5x lens. Images were processed using ImageJ and Avizo software.

2.4. Cell-seeding experiments

Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were cultured in MesenCultTM medium (Stemcell Technologies) in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were stained by 5 μM CellTrackerTM Green CMFDA (Invitrogen) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) for 45 min and then fresh DMEM for 30 min before experiments. For the cell seeding experiments, the cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 4 min. Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) was added to resuspend the cells to the final cell concentration of 106 cells/ml. One drop of 100 μl cell suspension was placed onto the hydrophobic surface of a 35 mm petri dish. The hydrophobicity of the surface prevented the cell suspension to spread and avoid cell loss, which was necessary for the cell seeding procedure. One end of the scaffold (12 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm) was put in contact with the cell drop. As the cell seeding procedure took only a few seconds, the cells did not adhere to the surface of the petri dish in such a short time and all the cells were drawn into the scaffold during experiments. The scaffold was then viewed by Prairie confocal microscope (488 nm).

2.5. In situ observation of capillary rising within biomimetic gradient scaffold

A high-speed CCD camera was used to observe in situ the capillary rise of water along the channels within biomimetic gradient scaffolds. The images were taken at 500 frames per second.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication of ceramic scaffolds with gradient channels by freeze-casting

Freeze-casting, also known as ice-templating, is a promising technique for fabricating tissue-engineering scaffolds with various types of materials, such as ceramics [15-16], polymers [14, 17], hydrogels [18], and their composites [19]. As shown in Fig. 1A, a modified freeze-casting technique was applied in our study to prepare scaffolds with gradient channels (see also Experimental Section). Because of its biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, and composition similar to bone, HA was used in this work to demonstrate a proof of concept. According to our previous studies, HA scaffolds prepared by freeze-casting have shown to have excellent mechanical properties [15-16], which makes them good candidates for load-bearing sites such as spinal fusion cage. In addition, freeze-casting is a very simple and inexpensive technique. Briefly, HA slurry was freeze-casted from the center to the edge of the mold, and was sublimated and sintered at 1,300°C to improve mechanical strength. XRD data of pristine and sintered HA shows no obvious difference, Supplementary Fig. S2. More importantly, the ice front velocity decreases greatly as compared with conventional freeze-casting as its freezing interface area always increase during the freezing process. As a result, the lamellar structure within the radially freeze-cast HA scaffold has an increasing channel width (λ) from the center to the edge, defined as “tip” and “base” respectively (Fig. 1B). We further studied the capillary effect of seeding cells into gradient scaffolds by contacting their tip or base side with a solution of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Due to the lack of capillaries in the wet scaffolds pre-perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the MSCs could only adhere to the outer surface (Fig. 1C and D). On the other hand, the MSCs were effectively self-loaded under capillary flow within dry scaffolds (Fig. 1E and F).

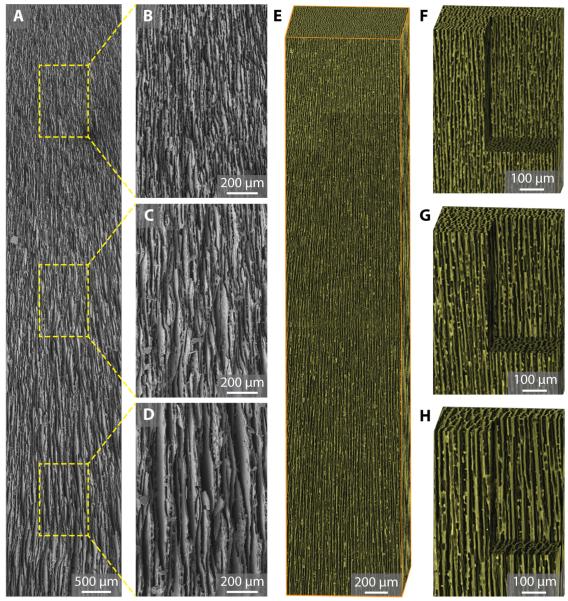

The gradient channels within the as-prepared scaffold were characterized by both scanning electron microcopy (SEM) and X-ray micro-tomography (Fig. 2). A low-magnification SEM image clearly shows the gradient channel structure over a large sample length of around 10 mm (Fig. 2A). As measured in the high-magnification SEM images in Fig. 2B–D, λ increases from 4.54 ± 0.88 μm (Fig. 2B, top), to 8.14 ± 1.24 μm (Fig. 2C, middle), and to 11.8 ± 2.47 μm (Fig. 2D, bottom), respectively. Same results were obtained from X-ray micro-tomography. Fig. 2E–H show the 3-D reconstructed images of the gradient scaffold. The dimensions of the bounding box is 1 mm × 1 mm × 5 mm in Fig. 2E, and 500 μm × 500 μm × 750 μm in Fig. 2F–H, respectively. A close-up view of the scaffold’s inner structure also shows an increase in λ (Fig. 2F–H, see also Supplementary Movie S1). It should be noted that gradient scaffolds also present different domain orientations of the lamellae (Supplementary Fig. S3), as in conventional freeze-cast scaffolds [16, 20].

Fig. 2.

Structural characterization of gradient scaffold. (A) Low-magnification SEM image of gradient scaffolds with channel width (λ) increasing from top to bottom. The sample length is around 10 mm. (B-D) High-magnification SEM image at different locations along the channel showing increasing channel width of (B) 4.54 ± 0.88 μm, (C) 8.14 ± 1.24 μm, and (D) 11.8 ± 2.47 μm, respectively. (E) 3-D reconstruction of gradient scaffolds from X-ray micro-tomography data. Bounding box dimension: 1 mm × 1 mm × 5 mm. (F-H) Close-up view of the scaffolds’ inner structure. Scale: 500 μm × 500 μm × 750 μm.

3.2. Self-seeding of cells within biomimetic ceramic scaffold with gradient channels

Uniform seeding of a large number of cells into porous scaffolds is considered to be a key step for the homogeneous tissue formation within bone grafts. Unfortunately, this still remains to be a great challenge because of the complex and tortuous architecture of many 3-D scaffolds [21]. At present, there are mainly two methods for cell seeding: static [22] and dynamic [21, 23-25]. When using a static method such as soaking a scaffold into a cell suspension [22], cells can only be found on the scaffold surface. More importantly, bone formation can hardly be observed in the scaffold center because the cells first attach to the periphery, preventing further migration and penetration into the scaffold [23]. On the other hand, dynamic methods, such as centrifuge [24], vacuum [23, 25], and oscillating perfusion [21], apply external forces that may damage the cells. In addition, dynamic methods need prolonged seeding time and complicated equipment [22]. Recently, capillary force was reported to facilitate cell seeding in 3-D scaffolds, especially for those with microporosity (pore size: 5–50 μm) [26]. Because our scaffolds have 3-D interconnected channel structures that mimic bone, we expect them to exhibit unique capillary behavior [17, 27-28].

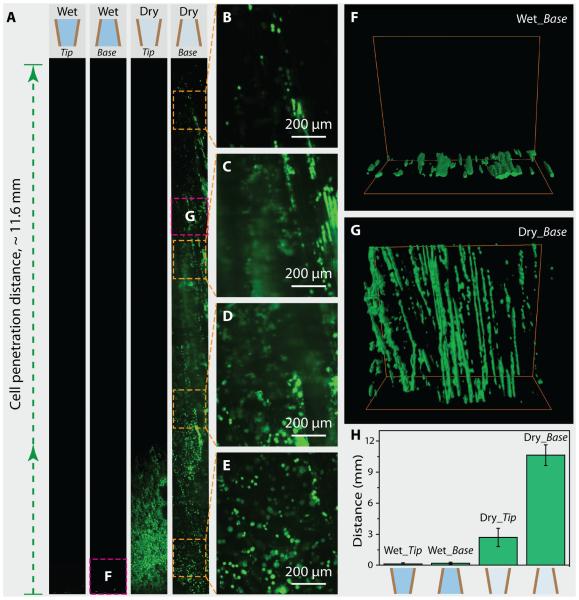

In order to study the capillary effect of these gradient channel structures, we performed four types of experiments: Wet_Tip, Wet_Base, Dry_Tip, and Dry_Base. In all these cases, cuboid samples of the same size (12 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm) were used. This size was selected based on our currently undergoing in vivo study (femur segmental defect model). With the channels facing along the longest axis (12 mm), the samples were manipulated to contact the MSC solution (100 μL, 1 × 106 cells/mL) only with their bottom surface. Fluorescent microscopy was then used to observe the result of cell seeding within the scaffolds (Fig. 3A–F). As shown in Fig. 3A, wet and dry scaffolds show a significant difference between seeding cells. In scaffolds pre-perfused with PBS, no cells penetrated into the scaffolds. Instead, cells were observed only on the bottom surface that contacted the cell solution (left two images of Fig. 3A). In the case of dry scaffolds, however, cells can penetrate along the channels (right two images of Fig. 3A). Interestingly, cells penetrated into the dry scaffold with an obviously longer distance (~11.6 mm) when in contact with the base side rather than with the tip side even though they have the same gradient channel structures. High-magnification images of the different positions along the gradient scaffold also show the obvious self-seeding of cells from the bottom to the top in the case of Dry_Base (Fig. 3B–E). The 3-D confocal fluorescent images show the bottom side of the Wet_Base sample and the top side of the Dry_Base sample, respectively, which are also indicated in Fig. 3A. In the case of Wet_Base, cells adhered to the outer surface (Fig. 3F). However, in the case of Dry_Base, cells were not only effectively loaded into a deep distance toward the tip but were well-aligned along the channels, as can be observed from the 3-D image (Fig. 3G, see also Supplementary Movie S2). Statistical data about the penetration distance of cells in all four experiments are shown in Fig. 3H. In each case, at least five samples were tested. The penetration distances were 0.12 ± 0.12 mm (Wet_Tip), 0.19 ± 0.12 mm (Wet_Base), 2.7 ± 0.88 mm (Dry_Tip), and 10.63 ± 1 mm (Dry_Base), respectively. These results demonstrate that the capillary is essential for the self-seeding of cells into gradient scaffolds, and the orientation of channels is crucial for this effect.

Fig. 3.

Cell-seeding experiments on wet and dry gradient scaffolds. (A) Fluorescent images of wet and dry scaffolds after seeding cells by contacting tip or base side of the scaffold with cell solution, respectively. Lacking capillary effect, cells adhered only to the outer surface of wet scaffolds pre-perfused with PBS (Wet_Tip and Wet_Base). In contrast, cell solution was driven along the channels within dry scaffolds by capillary force (Dry_Tip and Dry_Base). In the case of Dry_Base, cells penetrated all along the scaffold, which is around 12 mm in length. (B-E) High-magnification fluorescent images showing cells that are loaded all along the scaffold. (F) 3-D confocal fluorescent image showing that cells can only adhere to the edge of the Wet_Base sample without penetration. (G) 3-D confocal fluorescent image showing that cells are deeply loaded into the Dry_Base sample and aligned in the lamellar channels. The scanned locations are also indicated by the squares in (A). (H) Statistical data about the penetration distance of cells in all four experiments, which are 0.12 ± 0.12 mm (Wet_Tip), 0.19 ± 0.12 mm (Wet_Base), 2.7 ± 0.88 mm (Dry_Tip), and 10.63 ± 1 mm (Dry_Base), respectively.

3.3. Capillary rise within biomimetic ceramic scaffold with gradient channels

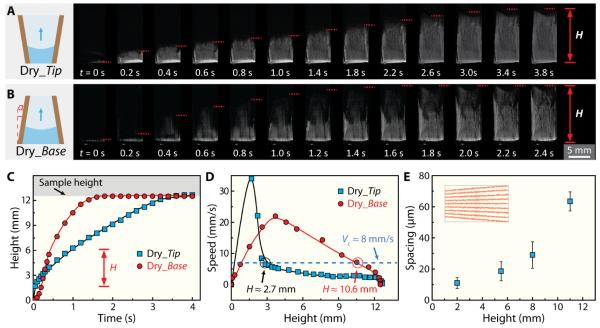

In order to understand the underlying mechanism and driving force of such self-seeding behavior, we observed the capillary flow within the gradient scaffold using a high-speed charge coupled device (CCD) camera at a rate of 500 frames per second. Sequential optical images in Fig. 4A and B show the capillary rises in dry scaffolds when in contact with their tip and base side, respectively (see also Supplementary Movie S3). The samples were around 12 mm in length. When plotting the height (H) of liquid as a function of time, two distinct behaviors were observed in Dry_Tip and Dry_Base. At the beginning, the liquid front was higher in Dry_Tip than in Dry_Base, but at the end, the liquid front in Dry_Base penetrated the whole sample and reached the top earlier than in Dry_Tip. The rising speed of the capillary can be obtained by differentiating the rising height with time. As can be seen from the plot of rising speed as a function of height in Fig. 4D, capillary flow in Dry_Tip first rose to a higher speed than in Dry_Base but decreased largely thereafter and became slower than in Dry_Base. If we consider that there is a minimum speed for the cells to flow together with liquid along the channels [29], we can determine from the v(H) curve the longest distance the cells can penetrate into the scaffold. For a critical speed of around 8 mm/s, the corresponding penetration distance of Dry_Tip and Dry_Base is around 2.7 mm/s and 10.6 mm/s, respectively, which is consistent with the experimental results measured from fluorescent images shown in Fig. 3H. This clearly supports our hypothesis that the self-loading of cells is governed by the spontaneous capillary flow generated by the gradient channels within the scaffold. In the samples used in the experiments, lamellar spacing (λ) of the channel was measured to increase from 11.0 ± 3.5 μm to 63.5 ± 6.1 μm.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the driving force for self-seeding of cells within gradient scaffold. (A-B) Sequential optical images showing capillary rise within dry gradient scaffolds with (A) the tip or (B) the base facing down and contacting deionized water. The images were taken with a high-speed charge coupled device (CCD) camera at 500 frames per second. (C) Height of water front (H) during capillary rise as a function of time. In both cases, water completely perfused the entire scaffolds (around 12 mm in length) within 3.5 s. (D) Speed of water front as a function of height. In both cases, the rising speed of water increased right after scaffolds contacted water, and decreased after reaching the maximum velocity. Comparing the penetrating distance of Dry_Tip (2.7 ± 0.88 mm) and Dry_Base (10.63 ± 1 mm) with the speed-height curve, a lowest critical speed of around 8 mm/s was found for the cells to flow with liquid along the channels of scaffolds. (E) Statistical data of lamellar spacing (λ) as a function of height, measured from cross section SEM images.

Capillary flow is widely used in nature by plants and animals, and in particular by tissues such as bone, to sustainably transport water and nutrients [10-13]. According to the Washburn’s equation, if we consider the lamellar channel structure in our work as a bundle of cylindrical tubes, the height (H) of the capillary flow as a function of time (t) can be written as:

| (1) |

where γ and η are the surface tension and viscosity of liquid, and λ is the spacing of the lamellar channel. The flowing speed (v) can therefore be obtained by differentiating Equation (1),

| (2) |

where λ0 is the lamellar spacing at the bottom, and α is the slope angle of the channels with respect to the vertical direction (inset of Fig. 4B). This equation doesn’t apply to the very beginning when the scaffold is in contact with the cell solution, i.e., H ≈ 0, and doesn’t take the gravity into account. At the very beginning, v increases faster in Dry_Tip than in Dry_Base, because the tip side has a smaller λ and thus a larger Laplace pressure as a driving force.

| (3) |

Later on, according to Equation (2), Dry_Base has a higher speed (v) than Dry_Tip, because the base side has a larger λ0, which is consistent with the experimental data in Fig. 4D. In other words, the capillary force is more sustainable in Dry_Base, and the resulting capillary flow is always maintained at a higher speed that favors cell penetration for a longer distance into the scaffold.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have successfully developed novel biomimetic ceramic scaffolds with gradient channel structure, which have self-seeding ability when in contact with MSC solution. Furthermore, we have demonstrated the underlying mechanism and driving forces for such unique self-seeding behavior and attribute it to the spontaneous capillary flow resulting from the gradient channel structure within the scaffold. Our results may open up new avenues for designing novel bone scaffolds. Indeed, scaffold morphology can be further controlled by modifying processing parameters such as cooling rate, solid loading or additive addition to the slurry [30-31]. This aspect will be of primary importance for the development of specific applications or, in our case, to further improve the seeding of cells. We believe that seeding cells more promptly and uniformly into the bone scaffold will facilitate bone regeneration and help simplify the clinical applications. Our research not only developed novel scaffolds for bone regeneration but also provides new insights into designing “smart” scaffolds with complex porous structures and biological functions that mimic natural tissues. Looking down the road, in vivo studies with these gradient scaffolds self-loaded with MSCs are currently being carried out. In addition to self-seeding of cells with capillary forces, other functions of the complex hierarchical structure of bone are still awaiting to be investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R01DE015633. The authors also acknowledge support of the X-ray tomography beamline 8.3.2 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which is supported by DOE’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Grace Lau, Dr. Yuan Chen, Mr. James Wu, Mr. Flynn Walsh, Dr. Lei Cheng, Dr. Xu Deng, and Dr. Laurent Gremillard for their kind help with the experiments and discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: An update. Injury. 2005;36(3):S20–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Persidis A. Tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(5):508–10. doi: 10.1038/8700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Van Heest A, Swiontkowski M. Bone-graft substitutes. The Lancet. 1999;353(1):S28–S9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Muschler GE, Nakamoto C, Griffith LG. Engineering principles of clinical cell-based tissue engineering. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(7):1541–58. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Place ES, Evans ND, Stevens MM. Complexity in biomaterials for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2009;8(6):457–70. doi: 10.1038/nmat2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bueno EM, Glowacki J. Cell-free and cell-based approaches for bone regeneration. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5(12):685–97. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fu Q, Saiz E, Rahaman MN, Tomsia AP. Toward Strong and Tough Glass and Ceramic Scaffolds for Bone Repair. Adv Func Mater. 2013;23(44):5461–76. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201301121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hollister SJ. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2005;4(7):518–24. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lapidot S, Meirovitch S, Sharon S, Heyman A, Kaplan DL, Shoseyov O. Clues for biomimetics from natural composite materials. Nanomedicine. 2012;7(9):1409–23. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zheng Y, Bai H, Huang Z, Tian X, Nie F-Q, Zhao Y, et al. Directional water collection on wetted spider silk. Nature. 2010;463(7281):640–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ju J, Bai H, Zheng YM, Zhao TY, Fang RC, Jiang L. A multi-structural and multi-functional integrated fog collection system in cactus. Nat Commun. 2012;3 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2253. 10.1038/ncomms2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prakash M, Quéré D, Bush JWM. Surface Tension Transport of Prey by Feeding Shorebirds: The Capillary Ratchet. Science. 2008;320(5878):931–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1156023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].da Fontoura Costa L, Viana MP, Beletti MEl. Complex channel networks of bone structure. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;88(3):033903. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang H, Hussain I, Brust M, Butler MF, Rannard SP, Cooper AI. Aligned two- and three-dimensional structures by directional freezing of polymers and nanoparticles. Nat Mater. 2005;4(10):787–93. doi: 10.1038/nmat1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Deville S, Saiz E, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. Freezing as a Path to Build Complex Composites. Science. 2006;311(5760):515–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1120937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Deville S, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. Freeze casting of hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27(32):5480–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Riblett BW, Francis NL, Wheatley MA, Wegst UGK. Ice-Templated Scaffolds with Microridged Pores Direct DRG Neurite Growth. Adv Func Mater. 2012;22(23):4920–3. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bai H, Polini A, Delattre B, Tomsia AP. Thermoresponsive Composite Hydrogels with Aligned Macroporous Structure by Ice-Templated Assembly. Chem Mater. 2013;25(22):4551–6. doi: 10.1021/cm4025827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Munch E, Launey ME, Alsem DH, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. Tough, Bio-Inspired Hybrid Materials. Science. 2008;322(5907):1516–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1164865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deville S, Adrien J, Maire E, Scheel M, Di Michiel M. Time-lapse, three-dimensional in situ imaging of ice crystal growth in a colloidal silica suspension. Acta Materialia. 2013;61:2077–86. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wendt D, Marsano A, Jakob M, Heberer M, Martin I. Oscillating perfusion of cell suspensions through three-dimensional scaffolds enhances cell seeding efficiency and uniformity. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;84(2):205–14. doi: 10.1002/bit.10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Buizer AT, Veldhuizen AG, Bulstra SK, Kuijer R. Static versus vacuum cell seeding on high and low porosity ceramic scaffolds. J Biomater Appl. 2013;29(1):3–13. doi: 10.1177/0885328213512171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang J, Asou Y, Sekiya I, Sotome S, Orii H, Shinomiya K. Enhancement of tissue engineered bone formation by a low pressure system improving cell seeding and medium perfusion into a porous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2006;27(13):2738–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Roh JD, Nelson GN, Udelsman BV, Brennan MP, Lockhart B, Fong PM, et al. Centrifugal seeding increases seeding efficiency and cellular distribution of bone marrow stromal cells in porous biodegradable scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(11):2743–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dong J, Uemura T, Kojima H, Kikuchi M, Tanaka J, Tateishi T. Application of low-pressure system to sustain in vivo bone formation in osteoblast/porous hydroxyapatite composite. Mater Sci Eng C. 2001;17(1-2):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Polak SJ, Rustom LE, Genin GM, Talcott M, Wagoner Johnson AJ. A mechanism for effective cell-seeding in rigid, microporous substrates. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(8):7977–86. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mao M, He J, Liu Y, Li X, Li D. Ice-template-induced silk fibroin-chitosan scaffolds with predefined microfluidic channels and fully porous structures. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2175–84. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Francis NL, Hunger PM, Donius AE, Riblett BW, Zavaliangos A, Wegst UGK, et al. An ice-templated, linearly aligned chitosan-alginate scaffold for neural tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101:3493–503. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dupire J, Socol M, Viallat A. Full dynamics of a red blood cell in shear flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(51):20808–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210236109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Deville S. Freeze-casting of porous ceramics: A review of current achievements and issues. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2008;10:155–69. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Munch E, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Deville S. Architectural Control of Freeze-Cast Ceramics Through Additives and Templating. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2009;92:1534–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.