Abstract

The recurrence of prostate cancer metastases to bone after androgen deprivation therapy is a major clinical challenge. We identified FN14 (TNFRSF12A), a TNF receptor family member, as a factor that promotes prostate cancer bone metastasis. In experimental models, depletion of FN14 inhibited bone metastasis, and FN14 could be functionally reconstituted with IKKβ-dependent, NFκB signaling activation. In human prostate cancer, upregulated FN14 expression was observed in greater than half of metastatic samples. In addition, FN14 expression was correlated inversely with AR signaling output in clinical samples. Consistent with this, AR binding to the FN14 enhancer decreased expression. We show here that FN14 may be a survival factor in low AR output prostate cancer cells. Our results define one upstream mechanism, via FN14 signaling, through which the NFκB pathway contributes to prostate cancer metastasis, and they suggest FN14 as a candidate therapeutic and imaging target for castrate resistant prostate cancers.

Keywords: TWEAK-Fn14 pathway, prostate cancer, bone metastasis, NFκB, AR

Introduction

Metastasis to the bone is one of the most clinically important features of prostate cancer (PC), although relatively little is known about specific pathways that promote tumor growth in the bone. Metastatic PC is treated with androgen deprivation therapy, which initially reduces symptoms and tumor cell growth, although recurrence of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) is almost universal (1). Reconstitution of androgen receptor (AR)-mediated signaling is a central mechanism leading to CRPC (2, 3). Although some level of AR output, measured by expression of AR target gene signatures, is almost always observed in prostate cancer, there is significant inter-tumoral heterogeneity, especially associated with progression (4–6). Following the development of castration resistance, a decrease in the level of an AR gene signature commonly expressed in prostate cancer indicates either reduced AR transcriptional activity or a shift in AR-dependent transcriptional specificity (6, 7). AR output is influenced by factors such as PTEN levels and the differentiation status of tumors (8–10). In the case of PTEN loss or N-cadherin expression, compensatory non-AR pathways are thought to significantly contribute to tumor growth.

Histopathology of end-stage bone metastases acquired at autopsy or as a result of surgical resections for spinal cord compressions or pathological fractures (11–13) has shown that bone metastases are heterogeneous, even within a single patient. Importantly, although nuclear AR staining is usually prominent in most cells, non-neuroendocrine AR negative tumor cells are clearly observed in both CRPC and treatment naïve metastases (11–14). These findings imply that AR-independent survival in the bone microenvironment occurs, and the mechanisms contributing to such survival are of great interest. The heterogeneity of metastatic disease suggests that second generation AR-directed therapies such as abiraterone and enzalutimide most likely will need to be complemented by therapies directed against non-AR pathways.

We describe here the characterization of Fn14 (TNFRSF12A) as a marker of clinical prostate cancer metastases and a determinant of experimental metastatic capability. Fn14, a TNF receptor family member, is the cognate receptor for TWEAK, a TNF-like cytokine, produced most prominently by infiltrating immune cells (15). Fn14 expression is low or absent in most normal tissues but can be activated by physiological mediators such as mitogens, hormones, and cytokines in epithelial, mesenchymal, and neuronal cell types (16). Activation of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis leads to context-dependent responses, including a prominent role in normal tissue repair and inflammation (15, 16). TWEAK stimulated Fn14 signaling occurs through multiple pathways including NFκB, MAPK, and CDC42/RAC (16, 17).

The over-expression of Fn14 has been reported in various solid tumors, where higher Fn14 expression in some tumor types has been shown to correlate with more advanced grade and poorer prognosis (18, 19), although it has not been previously addressed whether Fn14 is functionally required for an aggressive phenotype in vivo. Fn14 targeted agents based upon antibody binding specificities are being developed and have shown promise in preclinical oncology studies as a new class of therapeutics (20, 21). The study described here uniquely addresses the role of Fn14 in the development of bone metastasis, identifies the p50/p65 NFκB pathway as a sufficient and necessary downstream mediator of Fn14-dependent bone metastasis, and establishes an association between Fn14 expression and a low canonical AR gene signature phenotype.

Materials and Methods

ShRNA-mediated gene-silencing and expression-rescue in DU145/RasB1 cells

All genetically engineered cell lines were established using lentiviral vectors following standard procedures (22). Fn14 gene (TNFRSF12A) was silenced with two Fn14 shRNAs in the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector, designed by The RNAi Consortium (TRC) (Openbiosystems) and targeting the following sequences: 5′-ATGAATGAATGATGAGTGGGC -3′ (sh1) and, 5′-AGGATGGGCCAAAGCAGCCGG-3′ (sh2). Expression-rescued genes included Fn14 (Genecopeia), IKKβ S177E,S181E and NIKΔT3 in a pFUGW lentiviral vector with a FerH promoter (23). To achieve controlled expression of target genes, DU145/RasB1 cells stably expressing a Tet-On 3G transactivator were first established and further infected with a pFUGW lentiviral expression clone containing either AR (NM_000044.3) or mutant IκBαSR (IκBαS32A,S36A) under the control of the TRE3G promoter with an IRES-mCherry reporter. AR or IκBαSR expression was induced with 1μg/ml doxycycline (Dox).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were performed using the EZ magna ChIP A kit (Millipore) with a modified protocol (24). ChIP reactions were set up using rabbit monoclonal AR antibody (Clone ER179(2), Epitomics) at 4°C overnight. PCR primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

In vivo metastasis assay

Metastatic activity was determined using 6–7 week old male athymic nude mice (Ncr nu/nu) as previously described (22).

Tissue Microarray (TMA) Analysis

TMAs containing primary prostate cancer (UWTMA48) or metastases (UWTMA22) were constructed at the University of Washington (25). The NYU Prostate Cancer Biochemical Recurrence arrays, CAP6 TMA, was acquired from the Prostate Cancer Biorepository Network (PCBN, http://www.prostatebiorepository.org).

IHC staining conditions are described in Supplemental Table 2. The intensity scoring method for Fn14, TWEAK and p65: 0- none, 1 –weak, 2 – moderate/intermediate, 3 - strong and 4 - strong and obscuring details. The percentages of tumor cells scored for Fn14 and TWEAK were: 0 - none, 1 - up to 25%, 2 - up to 50%, 3 -up to 75% and 4 - up to 100%. Because a large number of cores contained a low percentage of nuclear p65 staining, an expanded scale was used for scoring: 0 -none, 1 -up to 10%, 2 - up to 25%, 3 - up to 50%, 4 - up to 75% and 5 -up to 100%. This system yielded a 16 or 20-point combined staining score. For Fn14 and TWEAK, combined scores were: <2 negative/weak, 3–6 intermediate, and 8–16 strong. For nuclear p65, combined scores were: 0 negative, 1–3 weak; 4 – 6 intermediate, and 8–20 strong.

Clinical outcome analysis using human tumor data sets

mRNA expression data under the GEO accession numbers GSE21034 (26) and GSE35988 (27) were used. The Taylor data set represents 151 primary and 19 metastatic tumors from patients treated by radical prostatectomy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. The Grasso data set represents a large cohort of heavily pre-treated patients with 28 lethal metastatic disease comprised of cancer-matched benign prostate tissues, 59 localized prostate cancers, and 35 metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers. The expression data and resulting Z-scores were log2 normalized.

A previously described androgen-responsive gene signature (28) was used to determine the correlation of Fn14 expression level and AR output. This gene set was scored for each tumor by summing the expression Z-scores within the human prostate cancer cohort. Tumors were median-stratified by Fn14 expression and the mean score of androgen response signature was determined in each group.

Statistical methods

In vivo animal results, TMA analysis and clinical outcome analysis are expressed as plots showing the median and box boundaries extending between 25th to 75th percentiles, with whiskers down to the minimum and up to the maximum value. All in vitro data are expressed as mean±SE. Data were analyzed using Prizm software (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and differences between individual groups were determined by Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post test for comparisons among 3 or more groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Log-rank test was used for survival curve analysis. The association of Fn14 and nuclear p65 was analyzed using contingency tables and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Fn14 is required for experimental prostate cancer bone metastasis

We previously described the development of a metastatic prostate cancer xenograft model, based upon the activation of Ras effector pathways in the DU145 cell line (22). Activation of the Ras pathway is commonly observed associated with prostate cancer progression (26, 29). To enrich for bone metastatic activity, DU145 RasG37 tumor cells were isolated from three independent bone metastases and expanded in culture. Inoculation of the bone derived clones (DU145/RasB), compared with the parental RasG37 transformed cells, demonstrated higher metastatic capacity as determined by more rapid development of metastasis and formation of more numerous and larger metastatic lesions (30). To determine whether changes in secreted factors or surface receptors correlated with bone metastatic capacity, supernatants from the cultured parental and bone-derived clones were assayed using a commercial antibody array designed to detect proteins within this functional class. Two of the most robust differences observed in all three bone-derived clones compared to the non-enriched parental culture were increased levels of the cytokine, TWEAK, and its cognate receptor, Fn14 (Figure 1A). Western blots performed on cell extracts confirmed high cell-associated Fn14 in bone-derived clones (Figure 1B). To analyze the functional significance in bone metastasis development of the Fn14/TWEAK pathway, Fn14 was depleted in DU145/RasB1 cells using two different lentivirus-encoded Fn14 shRNAs (Figure 1C). We investigated Fn14 in the development of metastasis because it is anticipated to act cell-autonomously. By contrast, TWEAK, a secreted product of the microenvironment, potentially can be contributed by a non-tumor source. Depletion of Fn14 had no effect on the in vitro growth rate (Suppl. Figure 1A). Following inoculation of Fn14-depleted cells, mice developed significantly less bone (Figure 1D) and brain metastasis compared to controls as measured by bioluminescent imaging at week 4 (Suppl. Figure 1C) and by the percentage of mice with bone lesions as determined by histology and/or X-ray at morbidity (Table 1). Mice inoculated with Fn14-depleted cells maintained a normal body weight (Suppl. Figure 1B) and survived longer (Figure 1E). Morbidity in these mice mainly was due to brain metastasis. The bone metastasis inhibitory effect was rescued by re-expression of Fn14 (Table 1), demonstrating specificity of the phenotype for Fn14 depletion. To address the generality of this finding, we depleted Fn14 in PC3 prostate cancer cells, originally isolated from a patient bone metastasis. PC3 cells express high levels of Fn14, and while depletion did not affect growth in vitro (Suppl. Figure 1D), it significantly inhibited bone metastasis as measured by bone metastasis development (Figure 1F), tumor burden and survival (Suppl. Figures 1E&F). Taken together, these data support a functional role for Fn14 in bone metastatic capability.

Figure 1.

Fn14 pathway activity is necessary for experimental bone metastasis. (A) TWEAK and Fn14 protein levels as determined by protein array analysis of conditioned media from parental DU145 (P), DU145/RasG37 (G37) and three bone metastatic clones (B1, B2 and B3). (B) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates measuring Fn14 in parental DU145(P), G37 and three bone metastatic clones (DU145/RasB1, B2 and B3). (C) Western blot analysis for Fn14 in DU145/RasB1 cells infected with lentivirus vector alone (EV) or lentivirus encoding silencing shRNA directed toward Fn14(Fn14shRNA1 or Fn14shRNA2). (D) Bioluminescence signal of bone metastasis per mouse for mice bearing tumor cells described in (C) at week 4. EV: n=9, shRNA1 and srRNA2: n=10 per group *p<0.05 vs control. (E) Survival curve of tumor bearing mice in the three groups from D. *p<0.05 vs EV. (F) The incidence of bone metastasis in mice bearing PC3/EV tumors and mice bearing PC3/Fn14 shRNA1 or 2 tumors. ** p<0.01 vs EV.

Table 1.

The role of the canonical and non-canonical NFκB pathway in bone metastasis development

| DU145/RasB1 EV | DU145/RasB1 Fn14KD EV | DU145/RasB1 Fn14KD Fn14 | DU145/RasB1 Fn14KD IKKBS177E/S181E | DU145/RasB1 Fn14KD NIKΔT3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone metastasis | 14/18 (78%) | 5/19 (26.3%) | 12/19 (63.2%) | 17/18 (94.4%) | 5/16(31.2%) |

| vs Fn14KD | **P<0.01 | *p<0.05 | *p<0.05 | NS |

Shown are the number and percentage of mice that developed bone metastasis. Fn14 depleted DU145/RasB1 (Fn14KD) were super-infected with lentiviruses expressing the indicated genes. Mice were euthanized at morbidity, between 6–9 weeks after tumor cell inoculation.

Fn14 is expressed in a high percentage of clinical prostate cancer metastases

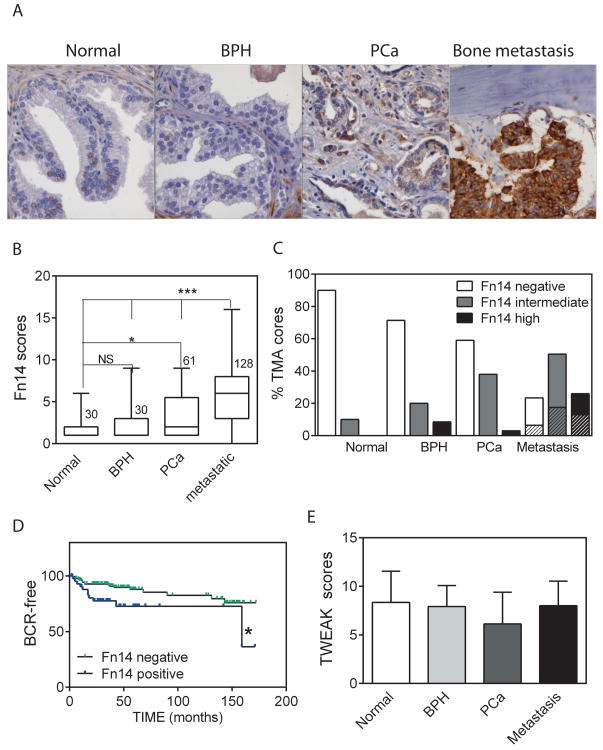

To analyze the prevalence of Fn14 expression in patient samples relative to prostate cancer progression, we performed immunohistochemistry using antibodies directed against Fn14 in tissue arrays containing a large number of bone and soft tissue metastases as well as normal prostate, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and primary prostate cancer specimens (Figure 2A). Representative images in bone metastases of either weak or strong staining, composed of membranous and cytoplasmic labeling, are shown in Suppl Figure 2A. A semi-quantitative scoring system of 0 to 16, reflecting intensity of staining and percentage of positive tumor cells, was used. The mean total score (Figure 2B) as well as individual intensity and extent (Suppl. Figure 2B) scores of metastatic samples were significantly higher than samples in the other categories. The distribution of scores is shown in Figure 2C, illustrating Fn14 expression in 10% of normal prostate epithelium, 25% of BPH, 40% of primary prostate cancer, and 75% of metastatic samples. The distribution of scores between bone and soft tissue metastases was similar. We next investigated the correlation of Fn14 expression in primary prostate specimens with tumor progression, measured as rising PSA levels with time after prostatectomy, usually an indication of recurrence outside the prostate (Figure 2D). Patients with Fn14 positive specimens (22.5% in this array) had significantly shorter time to biochemical recurrence, consistent with published data from an independent cohort of patients (18). These data from patient populations show that Fn14 expression occurs in a significant proportion of clinical bone metastases and support the correlation in primary prostate cancer of Fn14 expression with increased aggressiveness.

Figure 2.

Expression of Fn14 in normal and pathologic prostate tissues. (A) Representative histological images depicting normal prostate, BPH, PCa and bone metastasis stained for Fn14. B: bone. (B) Plots summarizing the Fn14 scores in different groups of clinical samples quantified for UWTMA22 and UWTMA48. The number of patient tissue samples is indicated. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001. (C) Percentage of tissue samples with negative/weak (0–2, open bar), intermediate (3–6, grey bar) or high (≥8, black bar) Fn14 expression from B. The shaded sections of the bars in the metastasis group represent soft tissue metastasis, while the solid sections represent bone metastasis. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve of biochemical recurrence rate (BCR) in Fn14 positive (≥3) and Fn14 negative (≤2) patient populations from CAP6 TMA. *p<0.05 with log rank test. (E) Average scores for TWEAK staining in epithelium in UWTMA22 and UWTMA48. n= 27 (normal), 28 (BPH), 51 (PCa), and 75 (metastasis).

An important question concerns the availability of the TWEAK ligand. TWEAK staining in tissue sections was observed across various cellular components including the cytoplasm, membrane and extracellular matrix. A high proportion of epithelial cells were stained in most sections, while the staining of stromal and immune components was variable (see Supplemental Figure 2C for examples of staining). Semi-quantitative analyses demonstrated that relatively similar levels of TWEAK ligand are constitutively present in normal and pathological prostate as well as metastatic tissues (Figure 2E).

The canonical NFκB pathway reconstitutes Fn14-depleted prostate cancer metastasis

The identification of signaling pathways that contribute to the establishment of prostate cancer bone metastasis is of therapeutic interest. Fn14 signaling activates canonical and non-canonical NFκB pathways, mediated by p65/RELA and p52/RELB complexes, respectively (16). Depletion of Fn14 in DU145/RasB1 cells inhibited TWEAK-stimulated p65 and p52 nuclear translocation by greater than 50% (Figure 3A). To determine if NFκB pathways are necessary for the development of DU145/RasB1 bone metastases, we made use of a doxycycline-inducible, degradation-resistant IκBα super repressor (IκBαSR), which prevents the translocation of p65 into the nucleus and indirectly inhibits synthesis of the p52 precursor, p100 (31). Prior doxycycline induction of IkBκSR led to inhibition of both NFκB pathways following TWEAK treatment in vitro (Figure 3B), while Fn14-dependent MAPK pathways were not affected (Suppl. Figure 3A). Figure 3C shows the experimental design for investigating the influence of NFκB signaling during metastasis development. IκBαSR was induced either from the time of tumor cell inoculation into the arterial circulation (day 0) or after micrometastases had been established (day 14). Expression of IκBαSR beginning at either day 0 or 14 led to significantly less metastases after 4 weeks as compared with control mice (Figure 3D), although IκBαSR had a relatively less dramatic effect on in vitro cell growth (Suppl. Figure 3B). The inhibition of metastasis by IκBαSR also was reflected by the maintenance of body weight (Suppl. Figure 3C) and increased survival (Figure 3E). These results indicate that blocking NFκB even after the establishment of micrometastases inhibits clinically-observable metastasis development.

Figure 3.

The NFκB pathway mediates the effects of TWEAK/Fn14. (A) Western blot analysis of nuclear p52 and p65 in DU145/RasB1 and DU145/RasB1 Fn14shRNA cells treated with TWEAK for various times. (B) Western blot of DU145/RasB1 cells expressing Tet-on TA and TRE3G-IκBαSR with and without prior doxycycline induction showing IκBα, p65(RelA), p52, p100 and Fn14 expression relative to time after TWEAK treatment. IκBα, Fn14 and the p52 precursor, p100, were detected in the cytoplasmic fraction; p65 and p52 were detected in the nuclear fraction. (C) Schematic of in vivo experimental design. Mice were inoculated on day 0 with DU145/RasB1 cells expressing Tet-on TA and TRE3G-IκBαSR. Mice were fed with doxycycline diets starting on day 0 or day 14 to induce IκBαSR expression and imaged weekly to monitor tumor burden. n=8–9 per group. (D) BLI analysis of bone and brain metastasis per mouse for tumor bearing mice described in C. Numbers represent mice that developed metastasis over total mice in each group at week 4. *p<0.05 vs control. (E) The survival rate of tumor bearing mice from D. (F) DU145/RasB1 cells depleted of Fn14 were super-infected with lentiviruses encoding Fn14, IKKB177E,S181E or NIKΔT3. The DU145/RasB1 EV cells are shown for comparison. Western blot shows nuclear p65 and p52 translocation with (+) or without TWEAK (−) treatment for 60 mins.

To determine whether either NFκB pathway individually is sufficient for replacing the Fn14-dependent signal leading to bone metastasis, we used a rescue approach in Fn14- depleted cells. A constitutively active form of IKKβ, IKKβS177E,S181E, was used to reconstitute the p50/p65 pathway, and a truncated form of NIK lacking the TRAF3 binding site (NIKΔT3) was used to rescue the p52/RELB pathway (23) (Suppl. Figure 3D). As shown in Figure 3F, IKKβS177E,S181E expressing Fn14-depleted cells demonstrated elevated levels of nuclear p65 with or without TWEAK treatment, while control cells demonstrated non-detectable nuclear p65. Similarly, NIKΔT3-expressing Fn14-depleted cells showed increased p52 nuclear translocation independent of TWEAK treatment (Figure 3F). Table 1 summarizes the bone metastatic capacity in each group, demonstrating that NFκB activation is sufficient to reconstitute Fn14-dependent metastasis. The bone metastasis phenotype was reconstituted in Fn-14 depleted cells by IKKβS177E,S181E expression, while NIKΔT3 expression alone appeared to be insufficient, suggesting a greater contribution by the p65 pathway. Taken together, these data show that NFκB activation is necessary and sufficient for the development of Fn14-dependent bone metastasis.

Nuclear NFκB p65 is observed in clinical prostate cancer metastases

To determine the prevalence of the canonical NFκB pathway in prostate cancer primary tumors and metastases, tissue arrays previously characterized for Fn14 labeling were stained with an anti-total p65 antibody. Labeling was observed both in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Nuclear labeling of prostate epithelial cells marked activation of the NF-κB pathway. Representative images of total p65 labeling in normal prostate and benign and malignant prostate pathologies are shown in Figure 4A. A semi-quantitative scoring system of 0 (negative) to 20 (extensive, strong labeling), reflecting a combination of staining intensity and the percentage of positive cells, was used to examine nuclear total-p65 expression across cores. Cores were marked as negative if less than 1% of the prostate epithelial cells were positive for nuclear NFκB p65 staining.

Figure 4.

NFκB activation in prostate cancer clinical samples. (A) Representative images and (scores) of tissue cores, including normal prostate tissue (0), BPH (0), primary prostate cancer (4) (UWTMA 48), and bone metastasis (3) (UWTMA22) stained for p65. In the bone metastasis core, the cytoplasmic staining is strong, while nuclear staining is <10%. (B) Plots summarizing the p65 scores in different groups of patient samples. The numbers of patient tissue samples in each group are: Normal (29), BPH (28), primary prostate cancer (55), and metastasis (115). **p<0.01 vs Normal, # # p<0.01, # # # p<0.001 vs BPH. (C) Percentage of TMA tissue samples with negative, weak (1–3), intermediate (4–6) or high (>6) nuclear p65 staining from B. (D) Tissue samples from B with 1–10% of cell nuclear p65 positive were further analyzed for staining intensity. Shown is the distribution of the selected samples for staining intensity with weak (1), intermediate/moderate (2) and strong (3) intensity. (E). Distribution of Fn14 (positive = ≥3) and nuclear p65 (positive = ≥1) expression in metastatic samples from B (n=103). p<0.05.

Primary prostate tumors and metastases had a statistically significant increase in the combined values of intensity and percentage positivity compared with normal prostate or BPH samples (Figures 4B&C). The relatively low overall scores are due to the majority of samples demonstrating a low overall frequency of nuclear staining, consistent with another large-scale study (32). This may be the result of transient p65 nuclear localization secondary to robust negative feedback mechanisms, which have been described for the p50/p65 pathway (33). Interestingly, the categorization of staining intensities for samples with 1–10% positive cells, which fall into the overall weak/intermediate categories, demonstrated a higher percentage of intense staining in metastatic samples (Figure 4D), suggesting relatively increased signaling in advanced disease samples. Notably, we also observed a significant association between Fn14 and nuclear p65 staining in metastatic prostate cancer specimens (Figure 4E), suggesting that Fn14 signaling leads to NFκB activation in clinical disease.

Fn14 expression is inversely correlated with AR status

One clinically-important property of tumor cells is AR transcriptional output, which can be heterogeneous within and between tumors (4, 14). We observed that Fn14 and TWEAK expression were significantly and highly expressed in AR negative compared to AR positive prostate cancer cell lines (Figure 5A), in agreement with published results (18). To determine if AR signaling was able to influence Fn14 or TWEAK expression in prostate cancer cells, we over-expressed AR in PC3 and DU145 cells using a doxycycline-regulated system. As shown in Figure 5B, when AR is induced in DU145/RasB1 cells, Fn14 and TWEAK RNA levels were decreased after DHT treatment, while the AR antagonist MDV3100 reduced this effect. Consistent with this finding, Fn14 protein levels also were reduced by the presence of AR (Figure 5C). In LAPC4 cells, Fn14 protein levels were regulated by endogenous AR in the anticipated pattern, demonstrating decreased and increased levels with DHT and MDV3100 treatment, respectively (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

AR down-regulates TWEAK and Fn14 expression. (A) RT-PCR analysis for Fn14 and TWEAK in two AR positive prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP and 22RV1, and two AR negative prostate cancer cell lines, PC3 and DU145. (B) RT-PCR analysis for AR, TWEAK and Fn14 in DU145/RasB1 cells expressing Tet-on TA and TREG3-AR with or without prior doxycycline induction for 2 days and subsequently treated with DHT (5nM) or MDV3100 (10μM) for 2 days. (C) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates for AR and Fn14 protein levels following doxycycline induction of AR in the indicated cells. Cells were treated or untreated with DHT(5nM) for 2 days. (D) Western blot analysis of Fn14 protein level in LAPC4 treated with DHT(5nM) or MDV3100 (10μM) in charcoal stripped serum for 2 days.

To interrogate Fn14 and TWEAK expression in patient populations, we analyzed a microarray data set from Memorial Sloan-Kettering composed of 131 primary and 19 metastatic prostate cancer samples (26). Because TWEAK and Fn14 expression appeared to be regulated approximately in parallel in cell lines, we analyzed the relative expression of the two genes in individual patient samples. Interestingly, Fn14 and TWEAK RNA levels in individual patients revealed a significant correlation (R=0.59, p<0.0001) (Figure 6A). TWEAK protein levels tend to be constitutively present, while Fn14 protein levels increase with progression (Figure 2), implying that there may be different post-transcriptional regulation of TWEAK and Fn14. We then analyzed AR pathway activation relative to Fn14 mean stratified expression by using a previously reported mRNA signature of AR target genes (28), which demonstrated an inverse relationship between Fn14 expression and AR transcriptional output (Figure 6B). This finding was validated in an independent data set (27) for a cohort of CRPC samples (Suppl. Figure 4A). The Fn14 high samples demonstrated more variability in the AR activity signature than the Fn14 low samples, suggesting more heterogeneity within Fn14 high prostate cancers.

Figure 6.

AR down-regulates Fn14 and TWEAK transcription in prostate cancer cells. (A) Correlation analysis of TWEAK and Fn14 expression levels in the MSKCC prostate cancer dataset. r=0.63, p<0.001. (B) AR activity signature genes expressed as a summed Z score for samples separated on the basis of Fn14 expression above the median (Fn14 high) or below the median (Fn14 low) in the MSKCC dataset. *** p<0.001. (C) Schematic of predicted AR response elements (ARE) in the Fn14 and TWEAK promoter regions. (D) qChIP analysis of AR and FOXA1 binding to predicted AREs in the TWEAK and Fn14 promoters/enhanchers illustrated in C. LNCaP cells were maintained in DHT-containing media. The binding activity of each protein to each site is given as a percentage of total input then normalized to individual immunoglobulin G (IgG) background. (E) TWEAK and Fn14 promoter reporter activity as measured by relative median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with vehicle (VEH) or DHT (5nM) or MDV3100 (10μM) for 72 hours. Mutant TWEAK (mutant A1=M1, mutant A3=M3) and Fn14 (mutant A5=M5, mutant A7=M7) promoter reporters were used as controls. *p<0.05 vs Veh, # p<0.05 vs DHT. Data represent the means±SEM.

AR down regulates the transcription of TWEAK and Fn14

To analyze whether AR directly regulates the transcription of Fn14 and TWEAK, potential androgen receptor response elements (AREs) were mapped in the TWEAK and Fn14 promoter/enhancer regions (Figure 6C). LNCaP cells, which express endogenous AR, were used to perform chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChiP) assays with anti-AR antibodies, which confirmed AR binding to two AREs (A1 and A3) in TWEAK and two AREs (A5 and A7) in Fn14 upstream regions (Figure 6D). Similar ChiP results were obtained in doxycycline-induced AR-expressing DU145 cells (DU145-AR) (Suppl. Figure 4B). In LNCaP, binding sites for FOXA1, an AR complex cofactor, were detected at the same positions as AR (Figure 6D). To determine whether AR activation was able to directly regulate TWEAK and Fn14 transcription, the TWEAK upstream region between −4006 and −2183 and the Fn14 upstream region between −2434 and +1 were separately cloned into an RFP reporter construct and transfected into LNCaP cells. The two reporters demonstrated approximately similar activity patterns. AR transcriptional activation with DHT suppressed reporter activity, while suppression of basal AR transcription with the AR antagonist, MDV3100, induced reporter activity (Figure 6E). Mutations in the defined AREs, especially TWEAK A1 and Fn14 A7, decreased DHT-dependent suppression and MDV-dependent induction relative to no treatment, demonstrating AR-mediated effects. Consistent with the results in LNCaP, AR-mediated suppression of reporter activity also was observed upon doxycycline induction in DU145 cells (Suppl. Figure 4C). Taken together, these data suggest AR binding to Fn14 and TWEAK upstream regions is transcriptionally suppressive. Because higher Fn14 and TWEAK RNA levels in patient samples correlate with lower AR signature gene expression, Fn14 and TWEAK may represent genes expressed in association with overall lower AR activity or altered AR specificity.

Discussion

Although bone metastasis is a primary reason for morbidity and mortality in patients with progressive prostate cancer, relatively little is known about the mechanisms responsible for establishing and expanding prostate cancer bone metastases (34). Using experimental models in addition to molecular and histological analyses of clinical samples, we present evidence that Fn14 is one determinant of prostate cancer bone metastatic capacity. Fn14 staining also has been observed in about 50% of clinical breast cancer bone metastases, although the number of samples analyzed was small (35).

Of particular interest, Fn14 expression suggests a mechanistic link between prostate cancer bone metastasis and inflammation since the TWEAK-Fn14 axis promotes local inflammation (15). An inflammatory microenvironment in the bone contributes to the so-called “vicious cycle” mediated by interacting stromal, immune, and tumor elements and resulting in bone remodeling and enhanced tumor cell survival and proliferation (36). From the data presented here, it appears that Fn14-expressing prostate cancer cells often produce autocrine TWEAK in addition to TWEAK secretion from infiltrating inflammatory cells. The bone metastasis model used in this study identifies the Fn14 pathway as one upstream regulator of NFκB signaling in prostate cancer and shows that the canonical NFκB pathway is sufficient to replace Fn14 downstream signaling in this context. Fn14-mediated responses are usually pro-inflammatory as a result of NFκB induction of inflammatory proteins including cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and metalloproteases (37). Thus, Fn14-dependent tumor responses are anticipated to increase inflammatory cell infiltration and activation. In addition, the Fn14-TWEAK axis has been shown to autonomously regulate tumor cells with respect to survival, proliferation, migration, and progenitor expansion (15, 16). Thus, both autonomous and non-autonomous Fn14-mediated functions may contribute to prostate cancer bone metastasis.

Our data are consistent with various pre-clinical models that support a role for NFκB in prostate cancer metastasis. An alternative mechanism of NFκB activation, loss of the DAB2IP tumor suppressor, leading to experimental prostate cancer soft tissue metastasis has been described (38). Of interest, coordinated RAS and NFκB activation occur in the DAB2IP model and in the model investigated here. DAB2IP loss regulates both RAS and NFκB activation, whereas the DU145/Ras model expresses constitutive RAS activation in addition to Fn14-regulated NFκB. It remains an open question as to how directly or indirectly RAS signaling is associated with Fn14 and TWEAK expression in prostate cancer. In another study, the manipulation of NFκB pathway components in human prostate cancer cell lines demonstrated that NFκB activation is necessary and sufficient for tumor cell growth following intra-tibial injections (39). Finally, a role for the NFκB pathway has been implicated in models of castration resistant growth (40, 41); castration resistance strongly correlates clinically with the development of metastasis (12, 13).

The increased presence of NFκB signaling in tumor tissue relative to normal tissue and a positive correlation with Fn14 expression was confirmed with immunohistochemical staining for nuclear p65 (Figure 4). The low frequency of positive cells may reflect the normally transient nature of p50/p65 signaling and are consistent with a recent study showing a significant association of even low numbers of nuclear p65 positive cells with higher Gleason score, increased biochemical recurrence, and the development of metastases (32, 42, 43).

Fn14 expression is regulated by a variety of extracellular stimuli including growth factors and hormones, although the molecular mechanisms of such regulation are mostly unknown (16). As shown here, Fn14 expression appears to increase in prostate cancer cells in which AR activity is suppressed, intrinsically low, or shifted in specificity. We describe an AR-dependent, negative regulatory component influencing TWEAK and Fn14 expression in prostate cancer cells. (Figure 6). The ability to identify prostate cancer cells with a modified AR response, which are anticipated to be less sensitive to ADT, is of potential utility considering the inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity of prostate cancer (4–6). Thus, an Fn14-targeted agent may permit the imaging and/or therapeutic treatment of metastatic tumors, especially cells that escape first line ADT due to modified AR signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The New Staff Research Project Grant (Y-N Liu), Taipei Medical University, Taiwan (TMU101-AE1-B20). We would also like to acknowledge Drs. Celestia Higano, Martine Roudier, Lawrence True, Paul Lange, Bruce Montgomery and Peter Nelson. The Prostate Cancer Donor Program is supported by the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50CA97186), the PO1 NIH grant (PO1CA085859), and the Richard M. LUCAS Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Mukherji D, Eichholz A, De Bono JS. Management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: recent advances. Drugs. 2012;72:1011–28. doi: 10.2165/11633360-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8253–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zong Y, Goldstein AS. Adaptation or selection--mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:90–8. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendiratta P, Mostaghel E, Guinney J, Tewari AK, Porrello A, Barry WT, et al. Genomic strategy for targeting therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2022–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Cao X, Wang L, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Li W, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Xu K, Yu J, et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell. 2009;138:245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma NL, Massie CE, Ramos-Montoya A, Zecchini V, Scott HE, Lamb AD, et al. The androgen receptor induces a distinct transcriptional program in castration-resistant prostate cancer in man. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:575–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulholland DJ, Tran LM, Li Y, Cai H, Morim A, Wang S, et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka H, Kono E, Tran CP, Miyazaki H, Yamashiro J, Shimomura T, et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting of N-cadherin inhibits prostate cancer growth, metastasis and castration resistance. Nat Med. 2010;16:1414–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crnalic S, Hornberg E, Wikstrom P, Lerner UH, Tieva A, Svensson O, et al. Nuclear androgen receptor staining in bone metastases is related to a poor outcome in prostate cancer patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:885–95. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roudier MP, True LD, Higano CS, Vesselle H, Ellis W, Lange P, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of end-stage prostate carcinoma metastatic to bone. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:646–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah RB, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM, Shen R, Ghosh D, Zhou M, et al. Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases: lessons from a rapid autopsy program. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9209–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleischmann A, Rocha C, Schobinger S, Seiler R, Wiese B, Thalmann GN. Androgen receptors are differentially expressed in Gleason patterns of prostate cancer and down-regulated in matched lymph node metastases. Prostate. 2011;71:453–60. doi: 10.1002/pros.21259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkly LC, Michaelson JS, Zheng TS. TWEAK/Fn14 pathway: an immunological switch for shaping tissue responses. Immunol Rev. 2011;244:99–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkles JA. The TWEAK-Fn14 cytokine-receptor axis: discovery, biology and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:411–25. doi: 10.1038/nrd2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortin SP, Ennis MJ, Schumacher CA, Zylstra-Diegel CR, Williams BO, Ross JT, et al. Cdc42 and the guanine nucleotide exchange factors Ect2 and trio mediate Fn14-induced migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:958–68. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang M, Narita S, Tsuchiya N, Ma Z, Numakura K, Obara T, et al. Overexpression of Fn14 promotes androgen-independent prostate cancer progression through MMP-9 and correlates with poor treatment outcome. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1589–96. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran NL, McDonough WS, Savitch BA, Fortin SP, Winkles JA, Symons M, et al. Increased fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 expression levels promote glioma cell invasion via Rac1 and nuclear factor-kappaB and correlate with poor patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9535–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Ekmekcioglu S, Marks JW, Mohamedali KA, Asrani K, Phillips KK, et al. The TWEAK receptor Fn14 is a therapeutic target in melanoma: immunotoxins targeting Fn14 receptor for malignant melanoma treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1052–62. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou H, Hittelman WN, Yagita H, Cheung LH, Martin SS, Winkles JA, et al. Antitumor activity of a humanized, bivalent immunotoxin targeting fn14-positive solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4439–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin J, Pollock C, Tracy K, Chock M, Martin P, Oberst M, et al. Activation of the RalGEF/Ral pathway promotes prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7538–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00955-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki Y, Calado DP, Derudder E, Zhang B, Shimizu Y, Mackay F, et al. NIK overexpression amplifies, whereas ablation of its TRAF3-binding domain replaces BAFF:BAFF-R-mediated survival signals in B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10883–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805186105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YN, Abou-Kheir W, Yin JJ, Fang L, Hynes P, Casey O, et al. Critical and reciprocal regulation of KLF4 and SLUG in transforming growth factor beta-initiated prostate cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:941–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06306-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrissey C, Roudier MP, Dowell A, True LD, Ketchanji M, Welty C, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation therapy and bisphosphonate treatment on bone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from the University of Washington Rapid Autopsy Series. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:333–40. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hieronymus H, Lamb J, Ross KN, Peng XP, Clement C, Rodina A, et al. Gene expression signature-based chemical genomic prediction identifies a novel class of HSP90 pathway modulators. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulholland DJ, Kobayashi N, Ruscetti M, Zhi A, Tran LM, Huang J, et al. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1878–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.JuanYin J, Tracy K, Zhang L, Munasinghe J, Shapiro E, Koretsky A, et al. Noninvasive imaging of the functional effects of anti-VEGF therapy on tumor cell extravasation and regional blood volume in an experimental brain metastasis model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26:403–14. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9238-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancro MP. Signalling crosstalk in B cells: managing worth and need. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:657–61. doi: 10.1038/nri2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gannon PO, Lessard L, Stevens LM, Forest V, Begin LR, Minner S, et al. Large-scale independent validation of the nuclear factor-kappa B p65 prognostic biomarker in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-kappa B and its inhibitor, I kappa B-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2532–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturge J, Caley MP, Waxman J. Bone metastasis in prostate cancer: emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:357–68. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chao DT, Su M, Tanlimco S, Sho M, Choi D, Fox M, et al. Expression of TweakR in breast cancer and preclinical activity of enavatuzumab, a humanized anti-TweakR mAb. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:315–25. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weilbaecher KN, Guise TA, McCauley LK. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:411–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min J, Zaslavsky A, Fedele G, McLaughlin SK, Reczek EE, De Raedt T, et al. An oncogene-tumor suppressor cascade drives metastatic prostate cancer by coordinately activating Ras and nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Med. 2010;16:286–94. doi: 10.1038/nm.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin R, Sterling JA, Edwards JR, DeGraff DJ, Lee C, Park SI, et al. Activation of NF-kappa B signaling promotes growth of prostate cancer cells in bone. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen CD, Sawyers CL. NF-kappa B activates prostate-specific antigen expression and is upregulated in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2862–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2862-2870.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin RJ, Lho Y, Connelly L, Wang Y, Yu X, Saint Jean L, et al. The nuclear factor-kappaB pathway controls the progression of prostate cancer to androgen-independent growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6762–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lessard L, Karakiewicz PI, Bellon-Gagnon P, Alam-Fahmy M, Ismail HA, Mes-Masson AM, et al. Nuclear localization of nuclear factor-kappaB p65 in primary prostate tumors is highly predictive of pelvic lymph node metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5741–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lessard L, Mes-Masson AM, Lamarre L, Wall L, Lattouf JB, Saad F. NF-kappa B nuclear localization and its prognostic significance in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2003;91:417–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.