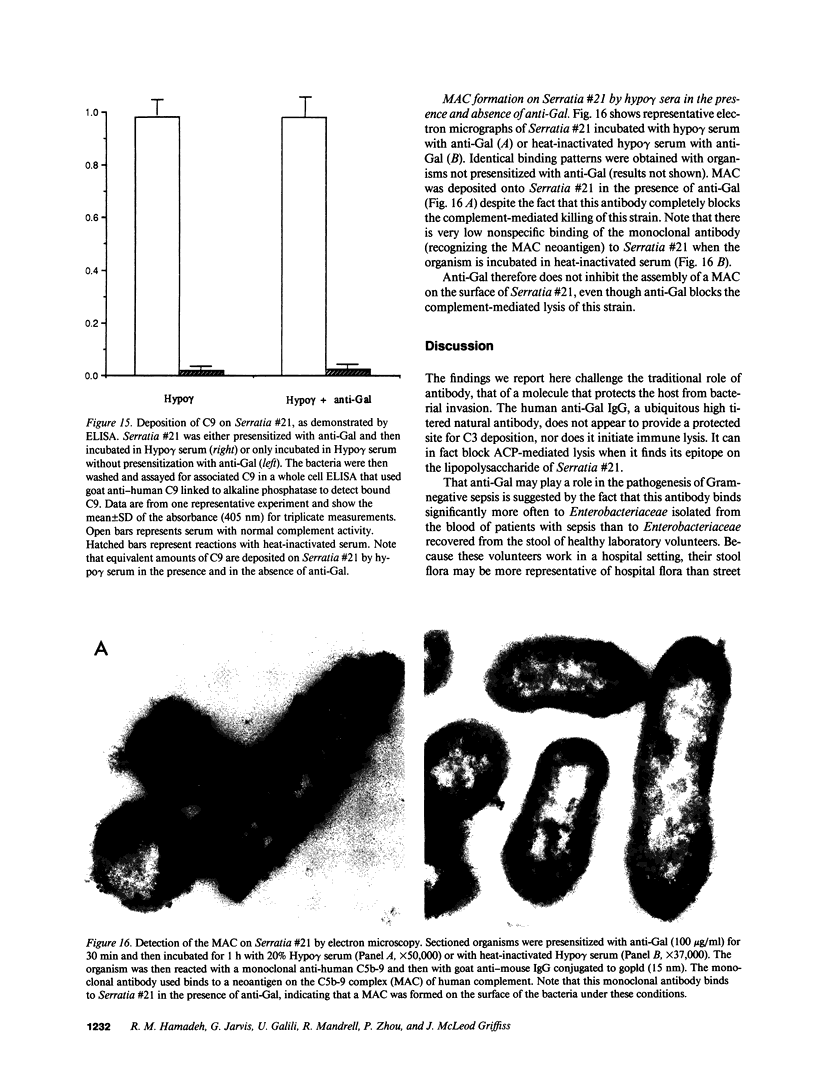

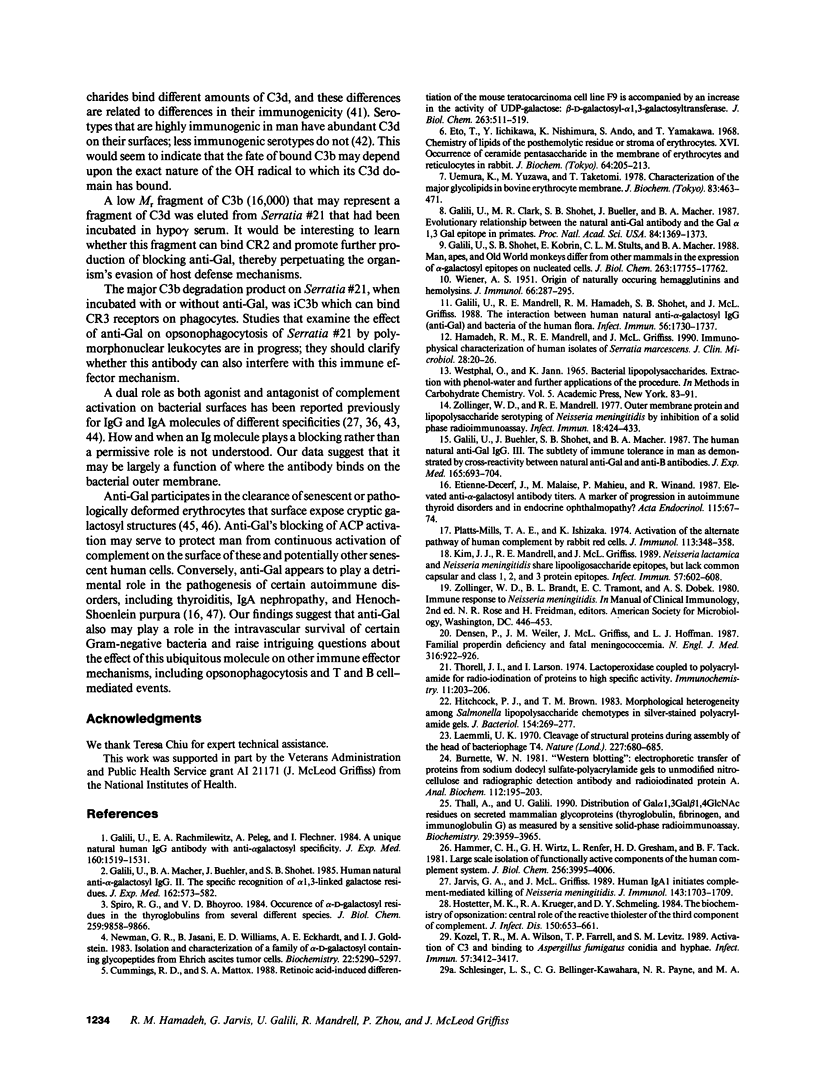

Abstract

One percent of circulating IgG in humans recognizes galactose alpha 1,3 galactose residues (anti-Gal) and is synthesized in response to stimulation by enteric bacteria. In this study, we found that the prevalence of binding of anti-Gal to blood isolates is significantly higher than its binding to normal stool isolates. When anti-Gal bound onto the lipopolysaccharide of a representative blood isolate, Serratia marcescens #21, it blocked its alternative complement pathway (ACP) lysis and made the organism serum resistant. In contrast, when anti-Gal bound to the capsular polysaccharide of a serum sensitive Serratia, #7, it increased ACP killing of this strain. The mechanism of blockade of ACP lysis by anti-Gal did not involve a decrease in the number of C3 molecules deposited onto Serratia #21 or an inhibition of the binding of C3b to its LPS, nor did it change the iC3b and C3d degradation products of bound C3b or prevent membrane attack complex formation on this organism. Our findings suggest that the effect of anti-Gal on immune lysis is dependent on the bacterial outer membrane structure to which it binds. We postulate that anti-Gal may play a role in the survival of selected Enterobacteriacae in Gram-negative sepsis by blocking ACP-mediated lysis of such bacteria by the nonimmune host, and that this effect depends on where anti-Gal finds its epitope on the bacterial outer membrane.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burnette W. N. "Western blotting": electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate--polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981 Apr;112(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings R. D., Mattox S. A. Retinoic acid-induced differentiation of the mouse teratocarcinoma cell line F9 is accompanied by an increase in the activity of UDP-galactose: beta-D-galactosyl-alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jan 5;263(1):511–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Densen P., Weiler J. M., Griffiss J. M., Hoffmann L. G. Familial properdin deficiency and fatal meningococcemia. Correction of the bactericidal defect by vaccination. N Engl J Med. 1987 Apr 9;316(15):922–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt A. E., Goldstein I. J. Isolation and characterization of a family of alpha-D-galactosyl-containing glycopeptides from Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochemistry. 1983 Nov 8;22(23):5290–5297. doi: 10.1021/bi00292a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Decerf J., Malaise M., Mahieu P., Winand R. Elevated anti-alpha-galactosyl antibody titres. A marker of progression in autoimmune thyroid disorders and in endocrine ophthalmopathy? Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1987 May;115(1):67–74. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1150067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto T., Ichikawa Y., Nishimura K., Ando S., Yamakawa T. Chemistry of lipid of the posthemyolytic residue or stroma of erythrocytes. XVI. Occurrence of ceramide pentasaccharide in the membrane of erythrocytes and reticulocytes of rabbit. J Biochem. 1968 Aug;64(2):205–213. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M., Pepys M. B. Role of C3 in in vitro lymphocyte cooperation. Nature. 1974 May 10;249(453):159–161. doi: 10.1038/249159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Buehler J., Shohet S. B., Macher B. A. The human natural anti-Gal IgG. III. The subtlety of immune tolerance in man as demonstrated by crossreactivity between natural anti-Gal and anti-B antibodies. J Exp Med. 1987 Mar 1;165(3):693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Clark M. R., Shohet S. B., Buehler J., Macher B. A. Evolutionary relationship between the natural anti-Gal antibody and the Gal alpha 1----3Gal epitope in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Mar;84(5):1369–1373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Clark M. R., Shohet S. B. Excessive binding of natural anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobin G to sickle erythrocytes may contribute to extravascular cell destruction. J Clin Invest. 1986 Jan;77(1):27–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI112286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Macher B. A., Buehler J., Shohet S. B. Human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl IgG. II. The specific recognition of alpha (1----3)-linked galactose residues. J Exp Med. 1985 Aug 1;162(2):573–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Mandrell R. E., Hamadeh R. M., Shohet S. B., Griffiss J. M. Interaction between human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobulin G and bacteria of the human flora. Infect Immun. 1988 Jul;56(7):1730–1737. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1730-1737.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Rachmilewitz E. A., Peleg A., Flechner I. A unique natural human IgG antibody with anti-alpha-galactosyl specificity. J Exp Med. 1984 Nov 1;160(5):1519–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Shohet S. B., Kobrin E., Stults C. L., Macher B. A. Man, apes, and Old World monkeys differ from other mammals in the expression of alpha-galactosyl epitopes on nucleated cells. J Biol Chem. 1988 Nov 25;263(33):17755–17762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. L., Rice J., Finlay-Jones J. J., McDonald P. J., Hostetter M. K. Analysis of C3 deposition and degradation on bacterial surfaces after opsonization. J Infect Dis. 1988 Apr;157(4):697–704. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman R. M., Waisbren B. A. Bacterial blocking activity of specific IgG in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975 Jan;19(1):121–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadeh R. M., Mandrell R. E., Griffiss J. M. Immunophysical characterization of human isolates of Serratia marcescens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Jan;28(1):20–26. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.1.20-26.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer C. H., Wirtz G. H., Renfer L., Gresham H. D., Tack B. F. Large scale isolation of functionally active components of the human complement system. J Biol Chem. 1981 Apr 25;256(8):3995–4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock P. J., Brown T. M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983 Apr;154(1):269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter M. K., Krueger R. A., Schmeling D. J. The biochemistry of opsonization: central role of the reactive thiolester of the third component of complement. J Infect Dis. 1984 Nov;150(5):653–661. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter M. K. Serotypic variations among virulent pneumococci in deposition and degradation of covalently bound C3b: implications for phagocytosis and antibody production. J Infect Dis. 1986 Apr;153(4):682–693. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis G. A., Griffiss J. M. Human IgA1 initiates complement-mediated killing of Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 1989 Sep 1;143(5):1703–1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner K. A., Hammer C. H., Brown E. J., Cole R. J., Frank M. M. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. I. Terminal complement components are deposited and released from Salmonella minnesota S218 without causing bacterial death. J Exp Med. 1982 Mar 1;155(3):797–808. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner K. A., Hammer C. H., Brown E. J., Frank M. M. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. II. C8 and C9 release C5b67 from the surface of Salmonella minnesota S218 because the terminal complex does not insert into the bacterial outer membrane. J Exp Med. 1982 Mar 1;155(3):809–819. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner K. A., Scales R., Warren K. A., Frank M. M., Rice P. A. Mechanism of action of blocking immunoglobulin G for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Invest. 1985 Nov;76(5):1765–1772. doi: 10.1172/JCI112167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner K. A., Warren K. A., Brown E. J., Swanson J., Frank M. M. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. IV. C5b-9 forms high molecular weight complexes with bacterial outer membrane constituents on serum-resistant but not on serum-sensitive Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Immunol. 1983 Sep;131(3):1443–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. J., Mandrell R. E., Griffiss J. M. Neisseria lactamica and Neisseria meningitidis share lipooligosaccharide epitopes but lack common capsular and class 1, 2, and 3 protein epitopes. Infect Immun. 1989 Feb;57(2):602–608. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.602-608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozel T. R., Wilson M. A., Farrell T. P., Levitz S. M. Activation of C3 and binding to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia and hyphae. Infect Immun. 1989 Nov;57(11):3412–3417. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3412-3417.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platts-Mills T. A., Ishizaka K. Activation of the alternate pathway of human complements by rabbit cells. J Immunol. 1974 Jul;113(1):348–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran B., Satapathy A. K., Das M. K. Naturally-occurring anti-alpha-galactosyl antibodies in human Plasmodium falciparum infections--a possible role for autoantibodies in malaria. Immunol Lett. 1988 Oct;19(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(88)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P. A., Vayo H. E., Tam M. R., Blake M. S. Immunoglobulin G antibodies directed against protein III block killing of serum-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae by immune serum. J Exp Med. 1986 Nov 1;164(5):1735–1748. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.5.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger L. S., Bellinger-Kawahara C. G., Payne N. R., Horwitz M. A. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J Immunol. 1990 Apr 1;144(7):2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H., Hammack C. A., Apicella M. A., Griffiss J. M. Instability of expression of lipooligosaccharides and their epitopes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1988 Apr;56(4):942–946. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.942-946.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro R. G., Bhoyroo V. D. Occurrence of alpha-D-galactosyl residues in the thyroglobulins from several species. Localization in the saccharide chains of the complex carbohydrate units. J Biol Chem. 1984 Aug 10;259(15):9858–9866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thall A., Galili U. Distribution of Gal alpha 1----3Gal beta 1----4GlcNAc residues on secreted mammalian glycoproteins (thyroglobulin, fibrinogen, and immunoglobulin G) as measured by a sensitive solid-phase radioimmunoassay. Biochemistry. 1990 Apr 24;29(16):3959–3965. doi: 10.1021/bi00468a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorell J. I., Larsson I. Lactoperoxidase coupled to polyacrylamide for radio-iodination of proteins to high specific activity. Immunochemistry. 1974 Apr;11(4):203–206. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(74)90329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Rosenfelder G., Wieslander J., Avila J. L., Rojas M., Szarfman A., Esser K., Nowack H., Timpl R. Circulating antibodies to mouse laminin in Chagas disease, American cutaneous leishmaniasis, and normal individuals recognize terminal galactosyl(alpha 1-3)-galactose epitopes. J Exp Med. 1987 Aug 1;166(2):419–432. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K., Yuzawa M., Taketomi T. Characterization of major glycolipids in bovine erythrocyte membrane. J Biochem. 1978 Feb;83(2):463–471. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIENER A. S. Origin of naturally occurring hemagglutinins and hemolysins; a review. J Immunol. 1951 Feb;66(2):287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisbren B. A., Brown I. A factor in the serum of patients with persisting infection that inhibits the bactericidal activity of normal serum against the organism that is causing the infection. J Immunol. 1966 Sep;97(3):431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. D., Levine R. P. How complement kills E. coli. II. The apparent two-hit nature of the lethal event. J Immunol. 1981 Sep;127(3):1152–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N. S., Issaragrasil S., Chieh C. W., Takaku F. Aplastic anaemia in the Orient. Br J Haematol. 1986 Jan;62(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollinger W. D., Mandrell R. E. Outer-membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide serotyping of Neisseria meningitidis by inhibition of a solid-phase radioimmunoassay. Infect Immun. 1977 Nov;18(2):424–433. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.2.424-433.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]