Abstract

Introduction:

To determine the effect of ovarian hormones on smoking, we conducted a systematic review of menstrual cycle effects on smoking (i.e., ad lib smoking, smoking topography, and subjective effects) and cessation-related behaviors (i.e., cessation, withdrawal, tonic craving, and cue-induced craving).

Methods:

Thirty-six papers were identified on MEDLINE that included a menstrual-related search term (e.g., menstrual cycle, ovarian hormones), a smoking-related search term (e.g., smoking, nicotine), and met all inclusion criteria. Thirty-two studies examined menstrual phase, 1 study measured hormone levels, and 3 studies administered progesterone.

Results:

Sufficient data were available to conduct meta-analyses for only 2 of the 7 variables: withdrawal and tonic craving. Women reported greater withdrawal during the luteal phase than during the follicular phase, and there was a nonsignificant trend for greater tonic craving in the luteal phase. Progesterone administration was associated with decreased positive and increased negative subjective effects of nicotine. Studies of menstrual phase effects on the other outcome variables were either small in number or yielded mixed outcomes.

Conclusions:

The impact of menstrual cycle phase on smoking behavior and cessation is complicated, and insufficient research is available upon which to conduct meta-analyses on most smoking outcomes. Future progress will require collecting ovarian hormone levels to more precisely quantify the impact of dynamic changes in hormone levels through the cycle on smoking behavior. Clarifying the relationship between hormones and smoking—particularly related to quitting, relapse, and medication response—could determine the best type and timing of interventions to improve quit rates for women.

Introduction

Tobacco use causes nearly half a million annual deaths in the United States1 and more than five million annual worldwide deaths.2 While there is evidence for increasing risk of mortality for smokers, especially for women,3 smoking cessation can prevent and reduce many of the harmful consequences of smoking.1 Despite being more likely to report a quit attempt than men,4 women have more difficulty than men achieving smoking abstinence,5–10 although see also Killen et al.11 Moreover, women demonstrate differences in important smoking behaviors that may influence successful cessation outcomes including greater and more variable withdrawal symptoms12–14 and greater cue-induced smoking cravings.15,16

Ovarian hormones and their fluctuations across the phases of the menstrual cycle may contribute to the greater difficulty that women experience when quitting smoking. Women with a natural monthly menstrual cycle (average length of 28–30 days) experience changes in ovarian hormone levels of estrogen and progesterone across the phases of the cycle.17,18 Levels of both estrogen and progesterone are low at the beginning of the follicular phase (i.e., menses, days 1 to 4 where 4 is the average length of menses). Estrogen then increases during the follicular phase with a peak at the end of the phase at ovulation (~day 14). The peak estrogen is followed by a decrease and then a small increase in the middle of the luteal phase (~day 21). Progesterone levels are low throughout the follicular phase, begin to rise moderately at the end of the follicular phase, and peak in the middle of the luteal phase (~day 21). Both estrogen and progesterone levels decrease rapidly during the late luteal (i.e., premenstrual) phase.

Both estrogen and progesterone have actions on brain function, influencing multiple reward-circuitry neurotransmitter systems.18,19 Estrogen has been shown in both preclinical and clinical research to increase the rewarding value of drugs of abuse20 including nicotine.21,22 For example, female rats demonstrate greater rewarding effects of nicotine compared to male rats when the females are intact, while ovariectomized female rats show no reward response to nicotine.22 Women also metabolize nicotine more quickly, especially women who are pregnant or taking oral contraceptives, suggesting a link to increased estrogen levels.23,24 A relationship between estrogen and nicotine metabolism has important clinical implications because quicker metabolism of nicotine is associated with more intense smoking,25 greater reward from nicotine,26 greater cravings to smoke after overnight smoking abstinence,26 and poorer cessation outcomes.27

Similar to estrogen, progesterone appears to have an impact on smoking behavior, but with effects in the opposite direction. Preclinical studies demonstrate decreased motivation for nicotine when progesterone levels are high (see Lynch and Sofuoglu18 for a review). For example, female rats demonstrate greater motivation for nicotine when progesterone levels are low and when there are greater estradiol levels relative to progesterone levels.28 Self-administration of nicotine decreases in female rats that are pregnant, a time when progesterone levels are high.29 Further, the administration of progesterone to non-human primates is associated with decreased nicotine self-administration.30 Taken together, these studies suggest that estrogen may promote addictive behaviors through increased reward while progesterone may be protective against addictive behaviors through decreased reward value.

The preclinical evidence suggesting that ovarian hormones may be a critical factor in the rewarding effects of nicotine highlights the importance of further elucidating the nature of the relationship between hormones and smoking. One prior qualitative review summarized 13 studies of menstrual cycle phase, a proxy for ovarian hormone levels, and withdrawal and cravings.17 While some studies found greater withdrawal and cravings during the luteal phase, compared to the follicular phase, there were limitations in the ability to draw conclusions because of mixed findings, small sample sizes, and variations across study methodologies. There has yet to be published a systematic examination of clinical, laboratory, and treatment studies that examine menstrual phase effects on a range of smoking behaviors and smoking-related symptomatology.

The purpose of this study is to conduct the first systematic and meta-analytic review of the literature on the relationship of ovarian hormones and menstrual cycle with smoking consumption-related behaviors (i.e., ad lib smoking, smoking topography, subjective effects of smoking) and smoking cessation-related behaviors (i.e., cessation and relapse, withdrawal, tonic craving, and cue-induced craving). The specific goals of this paper are to synthesize the current literature and to identify areas in need of additional research.

Methods

Systematic Review

A MEDLINE search was conducted in March 2014 to identify publications that included at least one menstrual cycle-related search term (e.g., “menstrual cycle,” “ovarian hormones,” “estrogen,” “progesterone”) and at least one smoking-related search term (e.g., “smoking,” “tobacco,” “cigarettes,” “nicotine”). A previous review of studies on menstrual cycle phase differences in withdrawal and cravings17 was examined for additional references. After removing duplicates and articles not published in English, the remaining publications were individually examined to determine whether they met inclusion criteria, namely that the study: (a) examined one or more types of behaviors related to smoking consumption or cessation (ad lib smoking, smoking cessation, smoking relapse, withdrawal, tonic cravings, cue-induced cravings, smoking topography, or subjective effects of smoking) and (b) examined differences in outcomes by menstrual cycle phase or by ovarian hormones. Information extracted from eligible papers included location of study (country), sample size, menstrual cycle phases assessed, whether biochemical confirmation of menstrual cycle phase occurred, whether women using oral contraceptives were included, and smoking-related outcome measures.

Meta-Analyses

After identifying studies for systematic review, articles were further evaluated for inclusion in meta-analyses. Studies were considered for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (a) provided estimates for both the follicular phase (or sub-phase) and the luteal phase (or sub-phase), and (b) provided the required statistical estimates for meta-analytic evaluation. The statistical estimates were extracted from published papers or obtained directly from the authors for two publications.31,32 These relatively broad criteria resulted in the identification of studies using multiple methodologies (see Results section for details). For example, some studies randomly assigned participants to either follicular or luteal phase, and compared outcomes between phases (e.g., likelihood of successful cessation, withdrawal, ad lib smoking). Other studies followed participants across multiple menstrual cycle phases and conducted within-person evaluations of cycle differences. Studies also varied in the measures utilized for each outcome. To generate commensurate effect size estimates, all comparisons between follicular and luteal phase were converted to Hedge’s G statistic,33 with corresponding standard error estimates. Studies were weighted based on 1/SE. Only outcomes with at least 5 Hedge’s G estimates were included in meta-analyses. Fixed-effects only models were calculated first, with commensurate testing of effect size heterogeneity (Q-statistic). When Q was significant, a random effects model was also calculated. All analyses were conducted using the Metafor package in R.34

Results

Study Characteristics

Four hundred thirteen publications were identified through the literature search and 36 of these articles met all the criteria to be included in the review (see Table 1 for study details and measured outcomes). The average sample size of the female participants across studies was 50 (SD = 56). Menstrual cycle phase was assessed by self-report and 22 studies also biochemically confirmed cycle phases (e.g., surge of luteinizing hormone levels which occurs just before ovulation). The majority of papers included free cycling women with three papers reporting that samples included women taking oral contraceptives.35–37 No study reported that they included women using an injectable contraceptive (e.g., Depo-provera).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Assessed Outcomes

| Outcomes assessed | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Country | Sample size— total | Sample size— women | % Caucasian | Number of menstrual phases assessed | Biochemical confirmation of phase? | Study design a | ad lib smoking | Smoking topography | Subjective effects of smoking | Smoking cessation | Smoking relapse | Withdrawal | Cravings— tonic | Cravings— cue induced |

| Allen et al. 31 | United States | 147 | 147 | 56 | 2 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| DeVito et al. 38 | United States | 160 | 45 | 31 | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | X | |||||

| Allen, Allen, et al. 39 | United States | 47 | 47 | 53 | 2 | Yes | W | X | |||||||

| Sakai et al. 40 | Japan | 29 | 29 | – | 3 | Yes | W | X | X | ||||||

| Schiller, et al. 41 | United States | 98 | 98 | 79 | See notee | Yes | – | X | X | ||||||

| Mazure et al. 42 | United States | 33 | 33 | 91 | 2 | – | B | X | |||||||

| Sofuoglu et al. 43 | United States | 64 | 30 | 30 | See noted | – | W | X | X | X | |||||

| Epperson et al. 35 | United States | 385 | 185 | 87 | 2 | – | B | X | |||||||

| Allen et al. 44 | United States | 202 | 202 | 82 | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | ||||||

| Gray et al. 45 | United States | 387 | 37 | 78 | 4 | Yes | W | X | |||||||

| Allen, Allen, Lunos, et al. 46 | United States | 138 | 138 | – | 2 | Yes | B | X | |||||||

| Allen, Mooney, et al. 47 | United States | 31 | 31 | 71 | 4 | Yes | B | X | |||||||

| Allen, Allen, Widenmier, et al. 48 | United States | 38 | 38 | – | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | ||||||

| Allen, Allen, and Pomerleau 49 | United States | 25 | 25 | 76 | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Sofuoglu et al. 50 | United States | 12 | 6 | 25 | See noted | – | W | X | X | ||||||

| Allen et al. 51 | United States | 202 | 202 | 82 | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Carpenter et al. 52 | United States | 44 | 44 | 82 | 2 | Yes | B | X | X | X | |||||

| Franklin et al. 53 | United States | 102 | 37 | 65 | 2 | – | B | X | |||||||

| Franklin et al. 54 | United States | 109 | 41 | 72 | 2 | – | B | X | X | ||||||

| Sofuoglu et al. 55 | United States | 12 | 12 | – | See noted | – | W | X | |||||||

| Allen et al. 32 | United States | 30 | 30 | 80 | 2 | Yes | W | X | X | ||||||

| Pomerleau et al. 56 | United States | 14 | 14 | 93 | 5 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| Snively et al. 57 | United States | 14 | 14 | 79 | 2 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| Perkins et al. 37 | United States | 78 | 78 | – | 2 | – | B | X | X | ||||||

| Marks et al. 58 | United States | 12 | 12 | – | 4 | Yes | W | X | X | ||||||

| Allen et al. 59 | United States | 21 | 21 | 86 | 2 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| Masson and Gilbert 36 | United States | 24 | 24 | – | 2 | Yes | W | X | |||||||

| Allen et al. 60 | United States | 32 | 32 | 91 | 3 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| DeBon et al. 61 | United States | 30 | 30b | 77 | 5 | Yes | W | X | X | ||||||

| Marks et al. 62 | United States | 9 | 9e | 100 | 5 | – | W | X | |||||||

| Pomerleau et al. 63 | United States | 22 | 22 | 96 | 5 | – | W | X | |||||||

| Pomerleau et al. 64 | United States | 9 | 9 | – | 3 | Yes | W | X | X | X | |||||

| Craig et al. 65 | United Kingdom | 30 | 20 | – | 2 | – | B | X | X | X | |||||

| O’Hara et al. 66 | United States | 36 | 22 | – | 2 | – | B | X | |||||||

| Steinberg and Cherek 67 | United States | 9 | 9 | – | 3 | – | W | X | X | ||||||

| Mello 68 | United States | 24 | 24 | – | 2 | – | W | X | |||||||

– = not applicable, not reported, or unable to calculate from available data; B = between-subjects; TNP = transdermal nicotine patch; W = within-subjects; X = the outcome was assessed in the study.

aBetween-subject or within-subject design for the comparison of menstrual cycle phase or ovarian hormones.

b15 female participants were smokers, and 15 female participants were non-smokers.

cOutcomes were examined by measurement of ovarian hormone levels.

dStudy of progesterone vs. placebo; all women participated during the early follicular phase.

eAll female participants met criteria for late luteal phase dysphoric disorder.

Behavior Related to Smoking Consumption

Ad Lib Smoking

Seventeen papers examined ad lib smoking, smoking reduction, or nicotine levels by menstrual cycle phase or ovarian hormones (Table 2) but not enough papers met all of the criteria listed above to conduct a formal meta-analysis. The most commonly studied outcome variable was cigarette smoking and these studies yielded mixed results: six studies reported no differences in number of cigarettes smoked by menstrual cycle phase49,59,60,63 or ovarian hormones,41,43 three studies reported greater cigarette smoking during the luteal phase,40,57,61 and five studies reported greater smoking during menses compared either to later in the follicular phase47,62,67 or other phases (Table 2).61,68

Table 2.

Studies of Ad Lib Smoking/Smoking Topography and Menstrual Cycle Phase/Ovarian Hormones

| Reference | Outcome measure | Type of measurement | Number of menstrual cycle phases | Menstrual cycle phases assessed | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. 69 | Nicotine levels | Response to nicotine nasal spray in the laboratory | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Trend level effect of greater maximum nicotine (p = .055) in follicular phase compared to luteal phase. |

| Sakai et al. 40 | CPD | Daily smoking log for two cycles | 3 | Follicular, luteal, menstrual | Greater smoking during luteal phase compared to follicular phase |

| Schiller et al. 41 | Number of cigarettes, smoking topography | 1-hr ad lib smoking period in the laboratory | See notea | See notea | Number of cigarettes smoked not associated with estradiol, progesterone, or estradiol to progesterone ratio. A larger number of puffs were significantly associated with lower levels of progesterone relative to estradiol. Greater intensity of puffs was associated with larger decreases in progesterone and estradiol from the baseline assessment to the laboratory appointment (a 1–2 week period of time). |

| Sofuoglu et al. 43 | Number of cigarettes | 2-hr ad lib smoking period in the laboratory | See noteb | See noteb | No significant differences for progesterone vs. placebo |

| Allen, Mooney, et al. 47 | Number of cigarettes | 2-hr ad lib smoking period in the laboratory | 4 | Follicular, luteal, late luteal, menstrual | Greater smoking during menstrual phase compared to the follicular phase |

| Allen, Allen, and Pomerleau 49 | CPD | Daily smoking log for 4 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | No significant differences by menstrual cycle phase |

| Pomerleau et al. 56 | CPD | Daily smoking log or 4 weeks | 5 | Post-menses, ovulation, post-ovulation, premenstrual, menstrual | Significant difference among phases in omnibus test, no post doc test reached significance, tread toward greater smoking in post-menses than postovulatory phase. |

| Snively et al. 57 | CPD | Daily smoking log for 8 weeks | 2 | Mid-to-late follicular, late luteal | Greater smoking in late luteal phase compared to mid-to-late follicular phase |

| Nicotine boost | Inpatient observation | 2 | Mid-to-late follicular, late luteal | No significant differences in nicotine boost by menstrual cycle phase | |

| Allen et al. 59 | CPD | Inpatient observation | 2 | Follicular, luteal | No significant differences by menstrual cycle phase |

| Allen et al. 60 | CPD | Daily smoking log for three days during each cycle phase | 3 | Follicular, luteal, late luteal | No significant differences by menstrual cycle phase |

| DeBon et al. 61 | CPD | Daily smoking log for one cycle | 5 | Follicular, ovulation, early luteal, late luteal, menstrual | Greater smoking during menstrual and luteal phases compared to ovulation |

| Marks et al. 62 | 6-point scale: 1 (not at all) to 6 (extreme) | Daily smoking log for two cycles | 5 | Post-menses, ovulation, post-ovulation, premenstrual, menstrual | Greater smoking during menstrual phase than post-ovulation phase |

| Pomerleau et al. 63 | CPD | Daily smoking log for 6 weeks | 5 | Post-menses, ovulation, post-ovulation, premenstrual, menstrual | No significant differences by menstrual cycle phase |

| Pomerleau et al. 64 | Nicotine intake | Smoking one cigarette in the laboratory | 3 | Early follicular, mid-to- late follicular, late luteal | Trend level effect (p < .10) of phase on nicotine intake (mid-to-late follicular > early follicular and late luteal). |

| Craig et al. 65 | Smoking reduction (% change) | Percent reduction in smoking on “no smoking” days | 2 | Midcycle, premenstrual | Greater smoking reduction in participant asked not to smoke for two days during the midcycle phase (90%) compared to premenstrual (i.e., late luteal) phase (78%). |

| Steinberg and Cherek 67 | Number of cigarettes, smoking topography | 2-hr ad lib smoking period in the laboratory | 3 | Premenstrual, menstrual, other | Greater smoking during menstrual phase compared to premenstrual and other phases. Participants took more puffs from their cigarettes and had longer puff durations when assessed during the “menstrual phase” (defined by the authors as a testing session on a day that “menstrual flow occurred” based on participant self-report; that is, the beginning of the follicular phase) compared to the “premenstrual” (5 days before menses onset) or “other” (any day that was not classified in one of the other two conditions) phases. |

| Mello et al. 68 | Change in CPD | Inpatient observation | 2 | 5 days before premenstrual phase, premenstrual | The majority of participants (70%) increase d their smoking during premenstrual phase by an average of 2.68 (SD = 0.44) CPD |

CPD = cigarettes per day. The menstrual phase (i.e., menses) occurs during the early portion of the follicular phase.

aOutcomes were examined by measurement of ovarian hormone levels.

bStudy of progesterone vs. placebo; all women participated during the early follicular phase.

Smoking Topography

Because only two studies were identified that examined smoking topography,41,67 there were insufficient data for a meta-analysis. The first study67 found significant differences in smoking topography measures (i.e., greater number of puffs, puff duration) by menstrual cycle phase while the second study41 reported significant differences in smoking topography measures (i.e., greater number of puffs, intensity of puffs) by ovarian hormones (Table 2).

Subjective Effects of Smoking

Four separate laboratory studies by one research group examined differences in the subjective effects of nicotine by menstrual cycle phase38 or for women receiving progesterone versus placebo.43,50,55 There were insufficient data for meta-analysis so the individual studies are reviewed below. The first study38 found lower reported positive subjective effects in response to intravenous (IV) nicotine (e.g., “high,” “feel good,” “want more”) for women in the luteal phase compared to women in the follicular phase. The second study55 included 12 women, all in the beginning of the follicular phase, who completed two laboratory sessions after overnight abstinence from cigarettes. During the laboratory sessions, participants were administered either 200mg progesterone or placebo. Progesterone administration was associated with lower ratings of “good effects” after two puffs of a cigarette compared to placebo. Ratings for “strength” and “head rush” were lower in the progesterone condition as well but these differences did not reach significance. In the third study,50 six women in the early follicular phase and six men participated in two laboratory sessions, each following overnight abstinence from smoking, during which they received either 200mg progesterone or placebo. Across the full sample, the rating of the “bad effects” was greater and “like drug” was lower in the progesterone condition than the placebo condition in response to IV nicotine. Responses to progesterone versus placebo for just female participants were not reported. Finally, participants in the fourth study43 were 30 women in the early part of the follicular phase and 34 men who were randomly assigned to receive 200mg of progesterone, 400mg progesterone, or placebo for four days. Participants were asked to abstain from smoking for the last three days of medication administration and then completed a laboratory session where subjective effects of smoking were rated after a 2-hr ad lib smoking period. Across the full sample, participants receiving placebo rated “drug strength” as greater compared to the other two conditions and participants who received 200mg of progesterone rated “drug liking” as lower compared to the other two conditions. The sex by medication interactions were not significant. Across the studies, there was evidence for decreased positive subjective affects and greater negative subjective effects of nicotine with the administration of progesterone or during the luteal phase (the phase when progesterone is at its highest levels).

Behavior Related to Smoking Cessation

Smoking Cessation and Relapse

There were insufficient data to conduct meta-analysis of menstrual cycle phase effects on smoking cessation or relapse. As summarized in Table 3, three studies reported no menstrual cycle phase differences in quit rates35,49 or time to smoking relapse,48 two studies reported better outcomes for quitting during the follicular phase,52,53 and three studies reported better outcomes for quitting during the luteal phase.42,46,51 The majority of smoking relapse occurred during the same phase as the quit attempt (Table 3). With regard to oral contraceptive use, Epperson and colleagues35 included 10 women taking oral contraceptives in their sample. Participants using oral contraceptives reported similar levels of negative affect as 47 participants not taking oral contraceptives during the first five days after attempting to quit smoking (M = 4.5, SD = 3.4 vs. M = 4.7, SD = 3.4). Quit outcomes for the subsample of participants using oral contraceptives versus participants not using oral contraceptives were not reported.

Table 3.

Studies of Smoking Cessation/Relapse and Menstrual Cycle Phase/Ovarian Hormones

| Reference | Reference note | Type of treatment | Length of treatment | Number of menstrual phases assessed | Menstrual cycle phases assessed | Random assignment to menstrual phase for quit attempt? | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazure et al. 42 | – | Bupropion (300mg) | 6 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | No | Greater point prevalence abstinence for participants who quit during the luteal phase (62.5%) compared to the follicular phase (29.4%, p < .05) at the end of the trial. No significant differences in quit rates by menstrual cycle phase at the three month follow-up (luteal phase, 18.8%; follicular phase, 11.8%; p > .05). |

| Epperson et al. 35 | – | TNP (21mg/ day), Naltrexone (0, 25, 50, 100mg) | 6 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | No | No significant differences in quit rates by menstrual cycle phase |

| Allen, Allen, Lunos, et al. 46 | Secondary analysis of Allen et al. 51 | Counseling | 26 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Noa | More participants relapsed during the follicular phase than the luteal phase (59.7% vs. 40.3%, p < .05). The majority of participants (65.9%) relapsed in the same phase in which they quit smoking. |

| Allen, Allen, Widenmier, et al. 48 | Secondary analysis of Allen et al. 51 | Counseling | 26 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Yes | No significant differences in time to relapse to smoking by menstrual cycle phase |

| Allen, Allen, and Pomerleau 49 | Secondary analysis of Allen et al. 51 | Counseling | 26 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Yes | No significant differences in quit rates by menstrual cycle phase |

| Allen et al. 51 | – | Counseling | 26 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Yes | More participants who quit during the follicular phase had relapsed to smoking after 14 days (84%) and 30 days (86%) compared to the participants who quit during the luteal phase (14 days, 65%; 30 days, 66%; ps < .001). With regard to the outcome variable of days until seven slips, participants who quit smoking during the follicular phase relapsed to smoking in a fewer number of days (M = 20.6 days, SD = 45.8) than participants who quit in the luteal phase (M = 39.2, SD = 59.0, p < .05). The majority of participants relapsed in the same phase in which they quit smoking (Continuous abstinence, 88%–91%; prolonged abstinence, 69%–76%). |

| Carpenter et al. 52 | – | TNP (21mg/ day), Counseling | 6 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | Yes | Non-significant trend of higher point prevalence abstinence after 2 weeks for participants who quit during the follicular phase (treatment initiators, 32%; intention to treat sample, 24%) compared to the luteal phase (19%, 16%). |

| Franklin et al. 53 | – | TNP (21mg/ day), Counseling | 8 weeks | 2 | Follicular, luteal | No | Greater abstinence for participants who quit during the follicular phase vs. the luteal phase after 3 days of treatment (81% vs. 48%, p < .05) and 1 week after the end of TNP treatment (69% vs. 29%, p < .05). |

– = not applicable, not reported, or unable to calculate from available data; TNP = transdermal nicotine patch.

aParticipants were women who had relapsed after a quit attempt and self-selected the timing of a second quit attempt.

Withdrawal

Sufficient data were available to conduct meta-analysis of withdrawal symptoms by menstrual cycle phase (Table 4). Of the 19 studies that included withdrawal symptoms as an outcome measure, 11 were excluded from the meta-analysis. Five of these did not include estimates for follicular versus luteal phases or sub-phases.36,51,55,56,65 Six studies52,57–59,61,64 conducted comparisons for follicular versus luteal phases, but provided insufficient information for calculating Hedge’s G effect size estimates and standard errors. The remaining eight studies were included in the meta-analysis.31,32,37,38,44,49,60,66 Estimates from nicotine deprivation study conditions were used when available.

Table 4.

Studies of Withdrawal/Cravings and Menstrual Cycle Phase/Ovarian Hormones

| Reference | Included in meta-analysis? | Treatment study? | Type of treatment | Number of menstrual phases assessed | Menstrual cycle phases assessed | Measure of withdrawal | Measure of cravings | Assessment setting | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. 31 | W | No | – | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | BQSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal by menstrual cycle phase during ad lib smoking. Greater withdrawal symptoms reported during luteal phase compared to the follicular phase during smoking abstinence. No significant differences in craving by menstrual cycle phase. |

| DeVito et al. 38 | W, C | No | – | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | BQSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal or cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Sakai et al. 40 | C | No | – | 3 | Follicular, luteal, menstrual | – | VAS scale (0–100) | Diaries completed at home | Greater cravings to smoke during menstrual phase compared to follicular or luteal phases |

| Sofuoglu et al. 43 | – | No | – | See notea | See notea | – | BQSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Lower BQSU Factor 1 score for 400mg progesterone compared to placebo and 200mg progesterone |

| Sofuoglu et al. 50 | – | No | – | See notea | See notea | MNWS (modified, 0–100 scale) | BQSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant main effects of progesterone vs. placebo for withdrawal lower BQSU total score for 200mg progesterone compared to placebo. |

| Allen et al. 44 | W, C | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | QSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in total withdrawal or cravings by menstrual cycle phase. Significantly greater report of increased appetite/weight gain (withdrawal symptom) for participants who quit during follicular phase compared to the luteal phase. Participants assigned to quit smoking during the follicular phase who reported higher anger and craving withdrawal symptoms were more likely to relapse to smoking at 14 days compared to those with lower anger and craving |

| Allen, Allen, Widenmier, et al. 48 | C | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | – | 8-point scale (0 = not at all, 7 = very strong) | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Participants in follicular phase reported greater cravings to smoke at wake-up compared to participants in luteal phase. Difference was no longer significant after controlling for level of nicotine dependence. |

| Allen, Allen, and Pomerleau 49 | W, C | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | MNSW- craving item | Diaries completed at home | Greater withdrawal reported during the luteal phase than the follicular phase. No significant differences in cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Allen et al. 51 | – | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | MNSW- craving item, QSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal or cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Carpenter et al. 52 | – | Yes | TNP, Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | MNSW- Craving item | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Greater total withdrawal, cravings, and fatigue reported by participants assigned to quit in the follicular phase compared to participants assigned to quit in the luteal phase. |

| Sofuoglu et al. 55 | – | No | – | See notea | See notea | NWSC | NWSC- craving item | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant difference in overall withdrawal for progesterone vs. placebo. Lower cravings to smoke on progesterone condition before participants smoked a cigarette. |

| Allen et al. 32 | W, C | No | TNP b | 2 | Follicular, late luteal | MNWS | MNSW- craving item, QSU | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Greater withdrawal reported in late luteal phase compared to follicular phase. No significant main effect of menstrual cycle phase on cravings (MNWS-craving item; QSU). TNP reduced cravings to a greater degree in the late luteal phase compared to the follicular phase (MNWS-craving item). |

| Pomerleau et al. 56 | – | No | – | 5 | Post-menses, ovulation, post-ovulation, premenstrual, menstrual | MNWS | MNSW- craving item | Diaries completed at home | No significant differences in withdrawal by menstrual cycle phase. Greater cravings to smoke during post-menses phase compared to the premenstrual phase. |

| Snively et al. 57 | – | No | – | 2 | Follicular, luteal | SJTWQ | SJTWQ | Inpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal or cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Perkins et al. 37 | W, C | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | DSM-IV symptoms, 0–100 scale | Desire to smoke, 0–100 scale | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal by menstrual cycle phase during pre- quit period. Greater increase in total withdrawal and each withdrawal symptom for participants quitting during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. No significant differences in cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Marks et al. 58 | – | No | – | 4 | Early follicular, mid-to-late follicular, mid- to-late luteal, late luteal | MNWS (modified; −50 to +50 scale, recoded to 0–50 for analyses) | VAS scale (−50 to +50, recoded to 0–50 for analyses) | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in changes in withdrawal or cravings in response to nicotine by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Allen et al. 59 | – | No | – | 2 | Follicular, luteal | MNWS | QSU | Inpatient research clinic/lab | No significant differences in withdrawal or cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Masson and Gilbert 36 | – | No | – | 2 | Early phase of cycle, menses/ late phase of cycle | SJTWQ | – | Outpatient research clinic/lab | No significant main effects of menstrual cycle phase for withdrawal. Oral contraceptive users reported more physical withdrawal than non-oral contraceptive users. |

| Allen et al. 60 | W | No | – | 3 | Follicular, luteal, late luteal | MNWS | MNWS craving item, QSU | Diaries completed at home | Greater withdrawal during the late luteal phase than the follicular or luteal phases. Greater cravings to smoke during the late luteal phase than the follicular phase on the NWSC Craving item. No differences in cravings to smoke by menstrual phase on the QSU. |

| DeBon et al. 61 | C | No | – | 5 | Follicular, ovulation, early luteal, late luteal, menstrual | MNWS (modified, added symptoms related to menstrual cycle, e.g., cramping) | – | Diaries completed at home | Greater smoking during menstrual phase compared to ovulation |

| Pomerleau et al. 64 | – | No | – | 3 | Early follicular, mid-to-late follicular, late luteal | MNWS (modified, −5 to +5 scale) | MNWS- craving item | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Trend (p < .10) toward main effect of phase on withdrawal scores. No significant differences in cravings by menstrual cycle phase. |

| Craig et al. 65 | – | No | – | 2 | Midcycle, premenstrual | TWQ | Frequency of urges to smoke, strength of urges to smoke | Diaries completed at home | No significant differences in withdrawal by menstrual cycle phase. Greater frequency and strength of urges to smoke for midcycle phase compared to premenstrual phase. |

| O’Hara et al. 66 | W | Yes | Counseling | 2 | Follicular, luteal | SJTWQ | – | Outpatient research clinic/lab | Greater withdrawal reported by women who quit during the follicular phase compared to the luteal phase 24, 48, and 72hr after quitting. |

– = not assessed, not applicable, not reported, or unable to calculate from available data; BQSU/QSU = (brief) questionnaire on smoking urges 70,71 ; C = this study was included in meta-analysis of cravings; MNWS = Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (also referred to as Nicotine Withdrawal Symptom Checklist; Hughes and Hatsukami 72 ); SJTWQ = Shiffman–Jarvik Tobacco Withdrawal Questionnaire (also referred to as the Shiffman-Jarvik Withdrawal Questionnaire; Shiffman and Jarvik 73 ); TNP = transdermal nicotine patch; TWQ = the withdrawal questionnaire (no reference provided); VAS = visual analog scale; W = this study was included in meta-analysis of withdrawal.

aStudy of progesterone vs. placebo; all women participated during the early follicular phase.

bParticipants were randomized to receive TNP or placebo patch over a seven day period for each of 2 menstrual cycle phases to assess changes in withdrawal symptoms by menstrual cycle and patch condition.

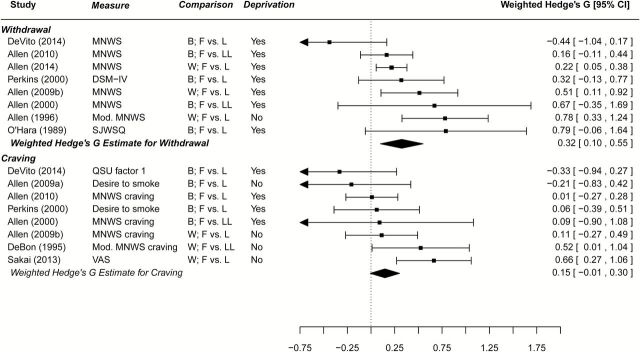

In a fixed effects-only model the mean weighted Hedges G effect size was 0.27 (95% CI = 0.15, 0.39; p < .001), with smokers exhibiting higher withdrawal scores in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. Given evidence for significant heterogeneity between studies (Q = 14.52, p < .05; I 2 = 57.2%), a random effects model was also calculated (Figure 1). The Hedge’s G statistic from this random effects model was 0.32 (95% CI = 0.10, 0.55; p < .01), with luteal phase demonstrating greater withdrawal symptoms than follicular phase.

Figure 1.

Meta-analytic findings for withdrawal and tonic cravings by menstrual phase. MNWS = Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; QSU = questionnaire of smoking urges; SJWSQ = Shiffman-Jarvik Withdrawal Symptom Questionnaire; VAS = visual analog scale; B = between subject comparison; F = follicular; L = luteal; LL = late luteal; W = within subject comparison. When deprivation = yes, estimates were calculated during a nicotine deprivation condition of the study. Weighted Hedge’s G for withdrawal calculated using a random-effects model (significant heterogeneity); for craving calculated using a fixed-effects only model (non-significant heterogeneity). Allen et al., 2009a is reference Allen, Allen, Widenmeir, et al.48 and Allen et al., 2009b is reference Allen, Allen, Pomerleau49.

This finding of greater withdrawal in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase may be related to premenstrual symptomatology which is greater during the late luteal phase40,60 and overlaps with withdrawal symptoms.32 While five studies assessed premenstrual symptoms;31,37,44,49,60 there were insufficient data to determine what impact premenstrual symptomatology may have on the relationship between menstrual cycle phase and withdrawal symptoms.

One study compared withdrawal symptoms in women currently using oral contraceptives (n = 12) and women not using oral contraceptives (n = 12).36 After overnight abstinence, women using oral contraceptives did not report greater overall withdrawal symptoms but did report greater physical withdrawal symptoms (e.g., heart beat faster) than women not using oral contraceptives (mean and SD not reported, p < .05). Women using oral contraceptives also demonstrated larger increases in heart rate and blood pressure after smoking two cigarettes. In a second study,37 results did not change when women taking oral contraceptives (n = 15 out of a total sample of 78) were excluded from the analyses.

Tonic Cravings

Sufficient data were available to conduct meta-analysis of cravings by menstrual cycle phase (Table 4). Of the 21 studies that included tonic craving as an outcome measure, 13 were excluded from the meta-analysis. Five of these did not include comparisons for follicular versus luteal phases.43,50,55,56,65 Eight studies included comparisons for follicular versus luteal, but provided insufficient data for computing Hedge’s G effect sizes and standard errors.31,51,52,57–60,64 The remaining eight studies were included in the analysis.32,37,38,40,44,48,49,61 Consistent with our methods for withdrawal, craving values were based on nicotine deprivation conditions when available. In a fixed-effects only model (Figure 1), there was a trend toward greater cravings during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase but this difference did not reach significance (Hedge’s G = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.01, 0.30; p = .06). There was no evidence for heterogeneity between effect size estimates (Q = 13.50, p > .05), therefore random-effects model estimates were not calculated.

Cue-Induced Cravings

In the first of two identified studies that examined cue-induced cravings to smoke by menstrual cycle phase,54 women in the luteal phase reported a greater cue-induced increase in desire to smoke compared to women in the follicular phase. In the second study,45 participants in the early follicular phase reported a greater increase in cravings compared to participants in the late luteal phase after exposure to smoking objects, although differences were no longer significant after controlling for exposure to non-smoking objects.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, a number of studies have identified that menstrual cycle and ovarian hormones influence smoking behavior. In the current study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, where possible, to examine menstrual cycle effects on seven aspects of smoking in order to synthesize research findings and ascertain areas in need of additional research. Thirty-six papers published over the past 30 years were identified that examined the impact of menstrual cycle phase or ovarian hormones on at least one aspect of smoking behavior. While there was evidence for menstrual cycle effects on all aspects of smoking behavior, some variables (e.g., cue-induced cravings, smoking topography) were studied by a small number of investigations and results were mixed for most variables. The research to date does not yet present a cohesive and clear picture of the relationship of menstrual cycle to smoking behavior.

Meta-analytic results found that women reported significantly greater withdrawal during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase quantifying the findings of one previous qualitative literature review.17 Additionally, there was a trend toward women reporting greater cravings during the luteal phase (marginally outside the criterion for statistical significance). Women report decreased positive and increased negative subjective effects of nicotine during the luteal phase38 and with the administration of progesterone 43,50,55 also suggesting luteal phase effects on smoking as progesterone levels are the highest during this phase of the menstrual cycle. However, the findings of greater withdrawal and cravings during the luteal phase are difficult to reconcile with the suggestion that progesterone is protective against addictive behaviors18 and preclinical evidence of decreased nicotine self-administration with higher progesterone in non-human primates and rats.18 Progesterone levels vary across the luteal phase, reaching a peak in the mid-luteal phase and decreasing dramatically by the end of the luteal phase. Studies are needed that examine the association of smoking with changes in progesterone within the luteal phase more closely to clarify the role of progesterone in smoking behavior at different points during the phase.

Other smoking-related variables—including ad lib smoking, smoking topography, cue-induced craving, and cessation—failed to demonstrate consistent phase effects. Among studies of ad lib smoking, various studies demonstrated no differences, greater smoking in follicular phase, or greater smoking in the luteal phase. The few studies of cue-induced cravings and smoking topography also found inconsistent results. The small number of studies and their mixed results limit the ability to draw conclusions about menstrual cycle effects on ad lib smoking, cue-induced cravings, and smoking topography. Results are similarly mixed for smoking cessation with studies reporting no differences by menstrual cycle phase, preferential outcomes for luteal phase, and preferential outcomes for follicular phase.

These mixed results found for many of the studied variables may be related to variations in methodologies and interventions.17,74 Many studies had small sample sizes and were based on retrospective rather than prospective trials. Across studies, the specific phases and sub-phases under investigation, methods to confirm cycle phase, and outcome variables have varied widely and in precision making cross-study comparisons difficult. The diverse methodology used in these studies also restricted the number of variables which could be examined using meta-analysis and limited the number of studies that could be included in the meta-analyses of withdrawal and cravings. These variations may have also impacted the meta-analytic outcomes, that is, the craving analysis did not reach statistical significance potentially due to variation in the measures of cravings (Figure 1) and the timing of craving measurement (e.g., early vs. late luteal). Further, smoking cessation studies differed in the type of interventions (behavioral vs. pharmacological treatment).74 Participants received diverse treatments (counseling, transdermal nicotine patch [TNP], bupropion, naltrexone) which may have had differential impacts on outcome related variables such as withdrawal and craving relief. While the current findings suggest that pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation interact with ovarian hormones with regard to cessation outcomes, the nature of these relationships has yet to be fully elucidated.

Most studies collapsed participants into menstrual cycle phases, with menstrual cycle serving as a proxy for ovarian hormone levels. The majority of the studies included in the review (21 out of 36 studies) compared two phases: the luteal phase and the follicular phase. The meta-analyses also compared the luteal phase to the follicular phase, as the two-phase comparison was the most common, and there were not sufficient data available to compare important sub-phases that may show different associations with smoking behavior due to changes in hormone levels within the phase (e.g., mid-luteal when progesterone is highest vs. late luteal when progesterone decreases to lower levels; early follicular during menses vs. mid- or late-follicular when estrogen levels rise to a peak). There is a need for more studies that use precision in measuring hormone levels during difference sub-phases of the menstrual cycle. For example, Schiller and colleagues41 found that women smoked more intensely when there were larger drops in progesterone and estrogen, which occur during the latter part of the luteal phase. There is also a need for studies to consider not just changes in estrogen and progesterone but how the two hormones interact with each other over the course of the menstrual cycle. Schiller et al.41 also found that higher levels of estrogen relative to progesterone, which occurs in the follicular phase, were associated with more intense smoking consistent with preclinical data suggesting that the estrogen may promote use of an addictive substance like nicotine18 and highlighting the importance of examining levels of estrogen and progesterone relative to each other by calculating the ratio of progesterone to estrogen. Studies that capture dynamic changes in ovarian hormone levels across the cycle can provide novel information about the best timing for women to attempt to quit smoking and best type of treatment to match the timing of the quit attempt. For example, Saladin and colleagues75 found that increases in progesterone levels (consistent with the early luteal phase) were associated with greater success at smoking cessation and, importantly, that these benefits were found in women using TNP but not women taking varenicline.

Linked to the need to determine ways to use information about the menstrual cycle to improve cessation outcomes, research is also needed that includes assessment of menstrual cycle phase at relapse. The majority of women and men relapse to smoking within a few days of the quit attempt76 and, for women, relapse more often occurs in the same phase of the menstrual cycle as the quit attempt.46,51 In addition, women appear to relapse to smoking at higher rates than men over longer periods of time77 highlighting the need for continued efforts to reduce relapse both in the short- and the long-term. Continued research on all aspects of smoking by menstrual cycle phase or ovarian hormones is needed to allow for additional and more finely-grained statistical analyses.

Future research may also benefit from taking a more comprehensive look at the progesterone and estrogen system (e.g., the impact of metabolites of the ovarian hormones). Allopregnanolone is a metabolite of progesterone that also is found in higher levels in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase69,78 and a study of female adult smokers found that allopregnanolone levels during smoking abstinence, relative to ad lib smoking, increased in the luteal phase and decreased in the follicular phase.69 Additional research can help clarify the relationship between progesterone and allopregnanolone level changes and smoking cessation including the effects of natural increases in progesterone versus administrated progesterone on smoking behavior and whether progesterone or its metabolites have benefits as a treatment for nicotine dependent smokers18 as preclinical research has demonstrated reduced nicotine withdrawal symptoms in response to allopregnanolone pretreatment.79

Premenstrual symptoms, which demonstrate overlap with withdrawal symptoms,32 are greatest during the late luteal phase40,44,58,60 and higher premenstrual symptomatology is associated with greater cigarette consumption, withdrawal, and relapse in some studies (e.g., Allen, Allen, and Pomerleau49; O’Hara et al.66; Perkins et al.37; Sakai and Ohaski40; although some results differ, see also Marks et al.62; Mello68; Pomerleau et al.64). The available data did not allow us to account for premenstrual symptoms in the association of withdrawal and menstrual cycle phase. It will be important for future work to clarify the role of premenstrual symptoms in the association between withdrawal and menstrual cycle phase. In addition, future studies should also examine the impact of successful treatment of premenstrual symptoms on cessation outcomes.

An estimated 11 million women in the United States take oral contraceptives making it the most commonly used method of contraception by women of reproductive age.80 Oral contraceptives which contain estrogen are related to faster nicotine metabolism23,81 which is itself related to worse smoking cessation outcomes.27 Only three studies in the review35–37 reported that they included women using oral contraceptives (see Results) and these data should be considered preliminary as the number of oral contraceptive users in each study was small (ns = 10–15). No research was identified that examined the association of an injectable contraception such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-provera), a progestin-only shot, to smoking behavior. Female smokers taking estrogen and progesterone-based contraceptives are a large yet understudied group in the smoking literature and it is not known how hormone-based contraceptive use impacts cessation outcomes. It can be hypothesized that contraceptives that deliver estrogen may hinder quit attempts while contraception that delivers progesterone may aid quit attempts, but very little is known at this time about the impact of hormone-based contraceptive use on smoking-related behaviors including differences for women receiving contraceptives that deliver estrogen and progesterone versus progesterone alone.

While menstrual cycle phases have an impact on smoking behavior, smoking behavior conversely effects the menstrual cycle. Smoking in women is associated with dysmenorrhea and menstrual irregularity9,82 and altered ovarian cycle and hormone levels.83,84 Compared to female nonsmokers, female smokers demonstrate changes in estrogen metabolism and lower circulating estrogen,85,86 a shorter reproductive lifespan,9,87,88 lower ovarian reserve,89,90 and quicker entry into all stages of the menopausal transition.91,92 Pregnancy-related smoking consequences include infertility, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and perinatal mortality.9,89 These data again highlight the importance of measuring hormone levels when conducting smoking research in women. Using information about the association of the menstrual cycle to smoking to improve cessation outcomes for women may also have important consequences on improving menstrual cycle health.

Conclusions

The impact of menstrual cycle phase on smoking behavior and cessation outcomes is complicated and continued research is needed to elucidate the relationships. Specifically, there is a need for studies to collect ovarian hormone levels to more precisely quantify the impact of hormone levels, changes in hormone levels, and the interactions of estrogen and progesterone on smoking behavior. It will be critical for future research to consider ovarian hormones as a system that continually undergoes dynamic changes. Clarifying the relationship between ovarian hormones and smoking, including cessation outcomes and interactions with medication response, would guide information on the best types and timings of interventions to help women achieve successful long-term cessation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P50-DA033945 [ORWH, NIDA, and FDA] to SAM; P50-DA016511 [ORWH, NIDA, and FDA] Component 4 to MES and KMG; P50-DA033942 [ORWH and NIDA] to SSA; R21-DA034840 to SSA; R01-DA008075 to SSA; and K02-DA031750 to KPC); and the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. KMG has received funding from Merck, Inc, and Supernus Pharmaceuticals for unrelated research. SAM has received investigator-initiated funding from Pfizer for unrelated research.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D. Finstad, K. Harrison, and S. Lunos for their help in obtaining data for the meta-analysis.

Data from this paper were presented at a Pre-Conference Workshop at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; February 25, 2015; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- 1. USDHHS. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:351–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34: 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perkins KA. Smoking cessation in women. Special considerations. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:391–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perkins KA, Scott J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1245–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, et al. Gender, race, and education differences in abstinence rates among participants in two randomized smoking cessation trials. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:647–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. USDHHS. Women and smoking. A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Gender differences in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Varady A, Kraemer HC. Do men outperform women in smoking cessation trials? Maybe, but not by much. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Boyd S, Moolchan ET, Lerman C, Pickworth WB. Gender differences in acute tobacco withdrawal: effects on subjective, cognitive, and physiological measures. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pang RD, Leventhal AM. Sex differences in negative affect and lapse behavior during acute tobacco abstinence: a laboratory study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: III. Correlates of withdrawal heterogeneity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Field M, Duka T. Cue reactivity in smokers: the effects of perceived cigarette availability and gender. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niaura R, Shadel WG, Abrams DB, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Sirota A. Individual differences in cue reactivity among smokers trying to quit: effects of gender and cue type. Addict Behav. 1998;23:209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carpenter MJ, Upadhyaya HP, LaRowe SD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Menstrual cycle phase effects on nicotine withdrawal and cigarette craving: a review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lynch WJ, Sofuoglu M. Role of progesterone in nicotine addiction: evidence from initiation to relapse. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:451–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson LR, Robinson TE, Becker JB. Sex differences and hormonal influences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carroll ME, Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Morgan AD, Cosgrove KP. Sex and estrogen influence drug abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Dell LE, Torres OV. A mechanistic hypothesis of the factors that enhance vulnerability to nicotine use in females. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:566–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Torres OV, Natividad LA, Tejeda HA, Van Weelden SA, O’Dell LE. Female rats display dose-dependent differences to the rewarding and aversive effects of nicotine in an age-, hormone-, and sex-dependent manner. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;206:303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, Jacob P., III Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strasser AA, Benowitz NL, Pinto AG, et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio predicts smoking topography and carcinogen biomarker level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sofuoglu M, Herman AI, Nadim H, Jatlow P. Rapid nicotine clearance is associated with greater reward and heart rate increases from intravenous nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1509–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Tyndale RF, Benowitz N, Lerman C. Nicotine metabolic rate predicts successful smoking cessation with transdermal nicotine: a validation study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lynch WJ. Sex and ovarian hormones influence vulnerability and motivation for nicotine during adolescence in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;94:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lesage MG, Keyler DE, Burroughs D, Pentel PR. Effects of pregnancy on nicotine self-administration and nicotine pharmacokinetics in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;194:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mello NK. Hormones, nicotine, and cocaine: clinical studies. Horm Behav. 2010;58:57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allen SS, Allen AM, Tosun N, Lunos S, al’Absi M, Hatsukami D. Smoking- and menstrual-related symptomatology during short-term smoking abstinence by menstrual phase and depressive symptoms. Addict Behav. 2014;39:901–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allen SS, Hatsukami D, Christianson D, Brown S. Effects of transdermal nicotine on craving, withdrawal and premenstrual symptomatology in short-term smoking abstinence during different phases of the menstrual cycle. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hedges LV. Statistical methodology in meta-analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wolfgang V. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Epperson CN, Toll B, Wu R, et al. Exploring the impact of gender and reproductive status on outcomes in a randomized clinical trial of naltrexone augmentation of nicotine patch. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Masson CL, Gilbert DG. Cardiovascular and mood responses to quantified doses of cigarette smoke in oral contraceptive users and nonusers. J Behav Med. 1999;22:589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perkins KA, Levine M, Marcus M, et al. Tobacco withdrawal in women and menstrual cycle phase. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeVito EE, Herman AI, Waters AJ, Valentine GW, Sofuoglu M. Subjective, physiological, and cognitive responses to intravenous nicotine: effects of sex and menstrual cycle phase. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1431–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allen SS, Allen AM, Kotlyar M, Lunos S, Al’absi M, Hatsukami D. Menstrual phase and depressive symptoms differences in physiological response to nicotine following acute smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sakai H, Ohashi K. Association of menstrual phase with smoking behavior, mood and menstrual phase-associated symptoms among young Japanese women smokers. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schiller CE, Saladin ME, Gray KM, Hartwell KJ, Carpenter MJ. Association between ovarian hormones and smoking behavior in women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mazure CM, Toll B, McKee SA, Wu R, O’Malley SS. Menstrual cycle phase at quit date and smoking abstinence at 6 weeks in an open label trial of bupropion. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sofuoglu M, Mouratidis M, Mooney M. Progesterone improves cognitive performance and attenuates smoking urges in abstinent smokers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allen AM, Allen SS, Lunos S, Pomerleau CS. Severity of withdrawal symptomatology in follicular versus luteal quitters: the combined effects of menstrual phase and withdrawal on smoking cessation outcome. Addict Behav. 2010;35:549–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gray KM, DeSantis SM, Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Menstrual cycle and cue reactivity in women smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allen SS, Allen AM, Lunos S, Hatsukami DK. Patterns of self-selected smoking cessation attempts and relapse by menstrual phase. Addict Behav. 2009;34:928–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Allen AM, Mooney M, Chakraborty R, Allen SS. Circadian patterns of ad libitum smoking by menstrual phase. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:503–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allen AM, Allen SS, Widenmier J, Al’absi M. Patterns of cortisol and craving by menstrual phase in women attempting to quit smoking. Addict Behav. 2009;34:632–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Allen SS, Allen AM, Pomerleau CS. Influence of phase-related variability in premenstrual symptomatology, mood, smoking withdrawal, and smoking behavior during ad libitum smoking, on smoking cessation outcome. Addict Behav. 2009;34:107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sofuoglu M, Mitchell E, Mooney M. Progesterone effects on subjective and physiological responses to intravenous nicotine in male and female smokers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Allen SS, Bade T, Center B, Finstad D, Hatsukami D. Menstrual phase effects on smoking relapse. Addiction. 2008;103:809–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, Leinbach AS, Larowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Menstrual phase effects on smoking cessation: a pilot feasibility study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Franklin TR, Ehrman R, Lynch KG, et al. Menstrual cycle phase at quit date predicts smoking status in an NRT treatment trial: a retrospective analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Franklin TR, Napier K, Ehrman R, Gariti P, O’Brien CP, Childress AR. Retrospective study: influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sofuoglu M, Babb DA, Hatsukami DK. Progesterone treatment during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: effects on smoking behavior in women. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 2001;69:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pomerleau CS, Mehringer AM, Marks JL, Downey KK, Pomerleau OF. Effects of menstrual phase and smoking abstinence in smokers with and without a history of major depressive disorder. Addict Behav. 2000;25:483–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Snively TA, Ahijevych KL, Bernhard LA, Wewers ME. Smoking behavior, dysphoric states and the menstrual cycle: results from single smoking sessions and the natural environment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:677–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Marks JL, Pomerleau CS, Pomerleau OF. Effects of menstrual phase on reactivity to nicotine. Addict Behav. 1999;24:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Allen SS, Hatsukami DK, Christianson D, Nelson D. Withdrawal and pre-menstrual symptomatology during the menstrual cycle in short-term smoking abstinence: effects of menstrual cycle on smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Allen SS, Hatsukami D, Christianson D, Nelson D. Symptomatology and energy intake during the menstrual cycle in smoking women. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8:303–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. DeBon M, Klesges RC, Klesges LM. Symptomatology across the menstrual cycle in smoking and nonsmoking women. Addict Behav. 1995;20:335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Marks JL, Hair CS, Klock SC, Ginsburg BE, Pomerleau CS. Effects of menstrual phase on intake of nicotine, caffeine, and alcohol and nonprescribed drugs in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pomerleau CS, Cole PA, Lumley MA, Marks JL, Pomerleau OF. Effects of menstrual phase on nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine intake in smokers. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pomerleau CS, Garcia AW, Pomerleau OF, Cameron OG. The effects of menstrual phase and nicotine abstinence on nicotine intake and on biochemical and subjective measures in women smokers: a preliminary report. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Craig D, Parrott A, Coomber JA. Smoking cessation in women: effects of the menstrual cycle. Int J Addict. 1992;27:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. O’Hara P, Portser SA, Anderson BP. The influence of menstrual cycle changes on the tobacco withdrawal syndrome in women. Addict Behav. 1989;14:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Steinberg JL, Cherek DR. Menstrual cycle and cigarette smoking behavior. Addict Behav. 1989;14:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Melllo NK, Mendelson JH, Palmieri SL. Cigarette smoking by women: interaction with alcohol use. Psychopharmacology. 1987;93:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69. Allen AM, al’Absi M, Lando H, Hatsukami D, Allen SS. Menstrual phase, depressive symptoms, and allopregnanolone during short-term smoking cessation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:427–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1467–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Shiffman SM, Jarvik ME. Smoking withdrawal symptoms in two weeks of abstinence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1976;50:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Franklin TR, Allen SS. Influence of menstrual cycle phase on smoking cessation treatment outcome: a hypothesis regarding the discordant findings in the literature. Addiction. 2010;104:1941–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Saladin ME, McClure EA, Baker N, et al. Increasing progesterone levels are associated with smoking abstinence in free cycling women smokers receiving brief pharmacotherapy. Nicotine Tob Res. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Piasecki TM. Relapse to smoking. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:196–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Stability of smoking status in the US population: a longitudinal investigation. Addiction. 2014;109:1541–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Genazzani AR, Petraglia F, Bernardi F, et al. Circulating levels of allopregnanolone in humans: gender, age, and endocrine influences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2099–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Thakre PP, Tundulwar MR, Chopde CT, Ugale RR. Neurosteroid allopregnanolone attenuates development of nicotine withdrawal behavior in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2013;541:144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. National Health Statistics Reports, no. 60. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Berlin I, Gasior MJ, Moolchan ET. Sex-based and hormonal contraception effects on the metabolism of nicotine among adolescent tobacco-dependent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Grossman MP, Nakajima ST. Menstrual cycle bleeding patterns in cigarette smokers. Contraception. 2006;73:562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Park J, Middlekauff HR. Altered pattern of sympathetic activity with the ovarian cycle in female smokers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H564–H568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Whitcomb BW, Bodach SD, Mumford SL, et al. Ovarian function and cigarette smoking. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24:433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gu F, Caporaso NE, Schairer C, et al. Urinary concentrations of estrogens and estrogen metabolites and smoking in caucasian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:58–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Raval AP. Nicotine addiction causes unique detrimental effects on women’s brains. J Addict Dis. 2011;30:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Allen EG, Sullivan AK, Marcus M, et al. Examination of reproductive aging milestones among women who carry the FMR1 premutation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2142–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Santoro N, Brockwell S, Johnston J, et al. Helping midlife women predict the onset of the final menses: SWAN, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2007;14:415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Caserta D, Bordi G, Di Segni N, D’Ambrosio A, Mallozzi M, Moscarini M. The influence of cigarette smoking on a population of infertile men and women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Plante BJ, Cooper GS, Baird DD, Steiner AZ. The impact of smoking on antimüllerian hormone levels in women aged 38 to 50 years. Menopause. 2010;17:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gold EB. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Liu Z, Lin H, Guo W. Factors that influence entry into stages of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2009;16:1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]