Abstract

Background

Ebola virus disease (EVD) has generated a large epidemic in West Africa since December 2013. This mini-review is aimed to clarify and illustrate different theoretical concepts of infectiousness in order to compare the infectiousness across different communicable diseases including EVD.

Methods

We employed a transmission model that rests on the renewal process in order to clarify theoretical concepts on infectiousness, namely the basic reproduction number, R0, which measures the infectiousness per generation of cases, the force of infection (i.e. the hazard rate of infection), the intrinsic growth rate (i.e. infectiousness per unit time) and the per-contact probability of infection (i.e. infectiousness per effective contact).

Results

Whereas R0 of EVD is similar to that of influenza, the growth rate (i.e. the measure of infectiousness per unit time) for EVD was shown to be comparatively lower than that for influenza. Moreover, EVD and influenza differ in mode of transmission whereby the probability of transmission per contact is lower for EVD compared to that of influenza.

Conclusions

The slow spread of EVD associated with the need for physical contact with body fluids supports social distancing measures including contact tracing and case isolation. Descriptions and interpretations of different variables quantifying infectiousness need to be used clearly and objectively in the scientific community and for risk communication.

Background

An epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) centred in three West African countries has been ongoing since December 2013, with limited international spread to other countries in Africa, Europe and the USA [1]. It is likely that the duration of this EVD epidemic, associated with a high case fatality risk (CFR) estimated at ~70% [2, 3], will extend well into 2015. To investigate the ongoing EVD transmission dynamics and consider a range of possible countermeasures, it is vital to understand the natural history and epidemiological dynamics of this disease.

Owing to the rapid progression of the EVD epidemic in West Africa, attempts have been made to clarify the fundamental epidemiological characteristics of EVD [1, 2, 4]. For instance, several studies have reported statistical estimates of the reproduction number, i.e., the average number of secondary cases generated by a single primary case, as a measure of the transmission potential of EVD [2, 5–12]. Despite substantial progress, it remains unclear how measures of infectiousness (or the transmissibility) of EVD should be communicated to the public and interpreted in light of the set of control interventions that could be considered in practical settings. Hence, the purpose of this mini-review is to comprehensively classify different theoretical aspects of infectiousness using a basic transmission model formulated in terms of a renewal process. This approach allows us to compare different measures of infectiousness across different communicable diseases and design possible countermeasures.

Discussion

Renewal process

Here we briefly review the definition of the basic reproduction number, R0 using the renewal process model [13]. Let i(t) represent the incidence (i.e. the transient number of new cases) at calendar time t. Assuming that the contribution of initial cases to the dynamics is negligible, the renewal process is written as

| 1 |

where A(s) is the rate of secondary transmission per single primary case at its infection-age (i.e., the time since infection) s. Using A(s), one can model the dependency of the transmission dynamics on infection-age [14]. By far the most commonly used measure of infectiousness is the basic reproduction number, R0, which is computed as

| 2 |

and it can be interpreted as the number of secondary cases produced by a single primary case throughout its entire course of infection in a completely susceptible population. Although the concept of R0 is well-known, it is important to note from (2) that R0 results from the integration over all infection-ages. It is well known that the mathematical definition of R0 in a heterogeneously mixing population is described by using the multivariate version of (1) and the next-generation matrix that maps secondary transmissions between and within sub-populations. R0 is defined as the largest eigenvalue of this matrix [15, 16]. Similarly, the definition of R0 can be adapted to the situation of periodic infectious diseases by handling the seasonal dynamics using a vector and employing Floquet theory (see e.g., [17]).

Although R0 is clearly a dimensionless quantity, the conceptual interpretation from the renewal process (1) permits us to regard R0 as the average number of infected cases produced “per generation”. For this reason, R0 could also be referred to as the basic reproductive ratio, as it could be calculated as the ratio of secondary to primary cases.

Adopting the mass action principle of the so-called Kermack and McKendrick epidemic model, a non-linear version of the renewal equation (1) follows [13]:

| 3 |

where s(t) is the fraction susceptible at time t, β(s) the rate of transmission per single infected individual at infection-age s, and Γ(s) the survivorship of infectiousness at infection-age s. Here we define the force of infection, λ(t) as

| 4 |

which yields a measure of the risk of infection in a susceptible population. The force of infection can be interpreted as the hazard of infection in statistical sense -- the rate at which susceptible individuals are infected [18]. In the classical Kermack and McKendrick epidemic model, λ(t) is modelled as proportional to the disease prevalence [13]. The force of infection is useful for the analysis of incidence data.

Comparison of three communicable diseases

Table 1 shows empirical estimates of R0 and the mean generation time for three different infectious diseases that are characterized by significantly different transmissibility and natural history parameters, i.e., measles, influenza H1N1-2009 and EVD [1, 19, 20]. The mean generation time, Tg can be mathematically derived from the transmission kernel in the renewal process (1), i.e.,

Table 1.

The basic reproduction number and mean generation time of three different diseases

|

5 |

The mode of transmission greatly differs for three diseases considered (Table 1). Measles is transmitted efficiently through the air while the transmission of influenza mostly occurs via droplet although airborne transmission is also possible in a confined setting [23]. In contrast, transmission of EVD is greatly constrained to physical contacts via body fluids [1]. Despite the differences in the mode of transmission for these diseases, it is important to note that the estimates of R0 for H1N1-2009 and EVD are not too different (Table 1). Does that indicate that influenza (H1N1-2009) and Ebola are similarly infectious?

While the average R0 for influenza and Ebola are similar, here we underscore that their underlying transmission dynamics show fundamental differences. This can be understood by analysing the intrinsic growth rate r for both diseases. Assuming that the early growth of each disease follows an exponential form, i.e., i(t) = i0exp(rt) (where i0 is a constant), the renewal equation (1) is rewritten as the so-called Euler-Lotka equation. Replacing i(t) in both sides of (1) by i0exp(rt) and cancelling exp(rt) from both sides, we obtain

|

6 |

yielding the relationship between R0 and the generation time,

|

7 |

where g(s) is the probability density function of the generation time. Equation (7) frequently appears in discussions of mathematical demography [24] and theoretical epidemiology [25], which is useful to describe how the relationship is determined between R0 and the intrinsic growth rate r as a function of the generation time distribution. For instance, if the generation time distribution follows the exponential distribution or Kronecker delta function, we obtain the well-known estimators of R0, i.e., R0 = 1 + rTg and R0 = exp(rTg), respectively [26]. Assuming that g(s) follows a gamma distribution with the coefficient of variation k, we have

| 8 |

It should be noted that it is possible that the right-tail of g(s) for EVD might have been underestimated if there were substantial number of secondary transmissions from deceased persons during funerals. Adopting the values of R0 and Tg given in Table 1, and assuming that the coefficient of variation of the generation time at 50%, the intrinsic growth rate of influenza H1N1-2009 is calculated as 0.125 per day, while that of EVD is calculated as 0.038 per day. Figure 1A compares the growth rates (r) of three representative communicable diseases for different values of the coefficient of variation of the generation time. An epidemic of measles appears to grow the fastest followed by one of influenza while an outbreak of EVD is expected to grow the slowest. Whereas the R0 for EVD is similar to that of influenza, the growth rate of EVD is far smaller than that of influenza. This is because each disease generation in the context of EVD transmission takes approximately two weeks, while each generation of new influenza cases occurs on a much shorter time scale - every 3 days on average. Moreover, EVD spreads comparatively slowly mainly by physical contact. This feature indicates that social distancing measures including contact tracing and case isolation could be powerful options for controlling EVD assuming that public health infrastructure exists for these interventions to be feasible [27].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the intrinsic growth rate of infectious diseases. (A) For a given R 0 and the mean generation time T g for a given infectious disease, the curves show the relationship between the intrinsic growth rate (r) and the coefficient of variation of the generation time of the disease. r of measles is the largest, followed by influenza, and then Ebola virus disease (EVD). (B) Temporal evolution in the number of new cases of measles, influenza, and Ebola virus disease using a coefficient of variation of the generation time at 50%. Parameter values are given in Table 1.

Thus, based on the infectiousness as measured by the growth rate of cases per unit time, it is very encouraging that EVD is far less dispersible than influenza. Although static countermeasures (e.g. mass vaccination at a certain age) can be planned using R0, the feasibility to deploy dynamic countermeasures, such as contact tracing and case isolation rests on the competition between the growth of cases and public health control, and in this context, the key parameter of infectiousness to assess the feasibility of control interventions is the intrinsic growth rate of cases.

Per contact risk of infection

We further decompose the rate of secondary transmission per single primary case in the renewal equation (3) into the product of the contact rate c(s) and the per-contact probability of infection p(s), i.e.,

| 9 |

Assuming that the per contact probability of infection, p is independent of infection-age, we have

|

10 |

The interpretation of p is straightforward, i.e., it can be regarded as the risk of successful secondary transmission given an infectious contact to a susceptible individual. Assuming that everyone is susceptible at time zero, R0 in (2) is rewritten as

| 11 |

As mentioned above, R0 for EVD is similar to that of influenza. Nevertheless, the infectious period, modelled by Γ(s) for EVD is longer than that of influenza. Assuming an identical contact rate, c, between EVD and influenza, equation (11) indicates that the per-contact probability of infection for EVD is smaller than that for influenza.

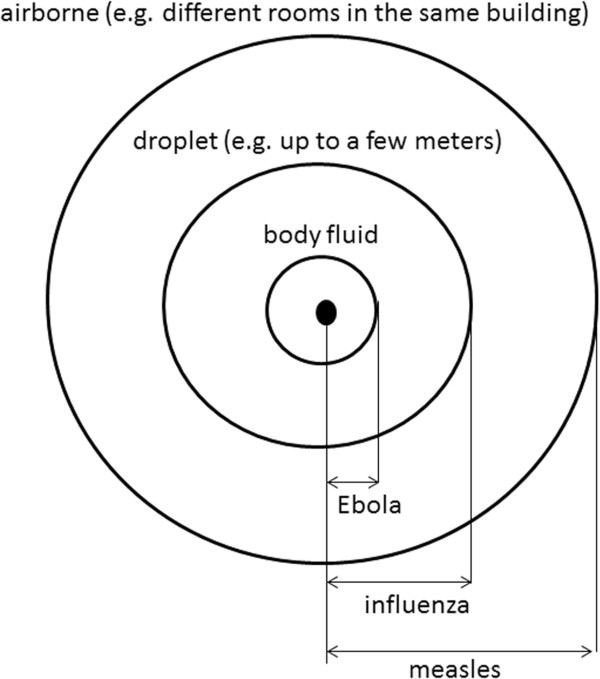

The mode of transmission differs across communicable diseases. Figure 2 illustrates the physical range of “contact” that can potentially lead to infection for three representative infectious diseases. Measles causes airborne transmission, and thus, it can lead to secondary infections across different rooms (or sometimes even across buildings). The extent of contact for EVD is very limited as it is highly constrained to physical contacts with body fluids. Hence, effective contact for EVD is limited to close contacts that might be unavoidable among healthcare workers and household members of cases.

Figure 2.

The extent of the contact by different mode of transmission. Airborne transmission can extend to different rooms and buildings, while the droplet transmission requires comparatively close contact. EVD is mainly transmitted through a physical exposure to body fluid of infected cases, and the extent of transmission is far less dispersible than those for measles and influenza.

Conclusion

We have comparatively discussed concepts of infectiousness for EVD in relation to other communicable diseases from a mathematical modelling point of view. The measure of infectiousness per generation of cases is R0. R0 offers a threshold principle and we have discussed that this measure is important for planning some static countermeasures such as mass vaccination. Based on R0, the overall infectiousness of EVD may be perceived to be similar to that of influenza. Nevertheless, the infectiousness per unit time for EVD was shown to be comparatively lower than influenza. The slow spread of EVD supports social distancing measures including contact tracing and case isolation. Moreover, the per-contact probability of infection for EVD is lower than that for influenza, and the mode of transmission also differs. These findings should also be regarded as encouraging news for healthcare workers who would have to have unavoidable and protected contact with EVD cases. In summary, there is a need for the use of clear and objective descriptions and interpretations of different variables quantifying infectiousness among the scientific community and for risk communication.

Acknowledgements

HN received funding support from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST program, RISTEX program for Science of Science, Technology and Innovation Policy, and St Luke’s Life Science Institute Research Grant for Clinical Epidemiology Research 2014. GC acknowledges financial support from the NSF grant 1414374 as part of the joint NSF-NIH-USDA Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases program, UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/M008894/1, and the Division of International Epidemiology and Population Studies, The Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- R0

The basic reproduction number

- EVD

Ebola virus disease

- CFR

Case fatality risk.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HN conceived of the study. HN conducted mathematical analyses and drafted the manuscript. HN and GC drafted figures and table together and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Hiroshi Nishiura, Email: nishiurah@m.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Gerardo Chowell, Email: gchowell@asu.edu.

References

- 1.Chowell G, Nishiura H. Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease (EVD): a review. BMC Med. 2014;12:196. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Ebola Response Team Ebola virus disease in West Africa–the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1481–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucharski AJ, Edmunds WJ. Case fatality rate for Ebola virus disease in west Africa. Lancet. 2014;384:1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Incident Management System Ebola Epidemiology Team, CDC; Ministries of Health of Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria, and Senegal; Viral Special Pathogens Branch, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC Ebola virus disease outbreak - West Africa, September 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:865–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishiura H, Chowell G. Euro Surveill. 2014. Early transmission dynamics of Ebola virus disease (EVD), West Africa, March to August 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althaus CL. PLOS Curr Outbreaks. 2014. Estimating the reproduction number of Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) during the 2014 outbreak in West Africa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisman D, Khoo E, Tuite A. PLOS Curr Outbreaks. 2014. Early epidemic dynamics of the West African 2014 Ebola outbreak: estimates derived with a simple two-parameter model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes MF, Piontti AP, Rossi L, Chao D, Longini I, Halloran ME, et al. PLOS Curr Outbreaks. 2014. Assessing the international spreading risk associated with the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Towers S, Patterson-Lomba O, Castillo-Chavez C. PLOS Curr Outbreaks. 2014. Temporal variations in the effective reproduction number of the 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamin D, Gertler S, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Skrip LA, Fallah M, Nyenswah TG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2014. Effect of Ebola progression on transmission and control in Liberia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasina F, Shittu A, Lazarus D, Tomori O, Simonsen L, Viboud C, et al. Eur Surveill. 2014. Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria, July to September 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Althause CL, Gsteiger S, Low N. Ebola virus disease outbreak in Nigeria: lessons to learn. Peer J PrePrints. 2014;2:e569v1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JAP. Mathematical epidemiology of infectious diseases: model building, analysis and interpretation. Chichester: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiura H. Time variations in the generation time of an infectious disease: implications for sampling to appropriately quantify transmission potential. Math Biosci Eng. 2010;7:851–869. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2010.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JA, Metz JA. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J Math Biol. 1990;28:365–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiura H, Chowell G, Safan M, Castillo-Chavez C. Pros and cons of estimating the reproduction number from early epidemic growth rate of influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacaër N, Ait Dads el H. On the biological interpretation of a definition for the parameter R0 in periodic population models. J Math Biol. 2012;65:601–621. doi: 10.1007/s00285-011-0479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrington CP. Modelling forces of infection for measles, mumps and rubella. Stat Med. 1990;9:953–967. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine PE. Herd immunity: history, theory, practice. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:265–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boëlle PY, Ansart S, Cori A, Valleron AJ. Transmission parameters of the A/H1N1 (2009) influenza virus pandemic: a review. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5:306–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inaba H, Nishiura H. The state-reproduction number for a multistate class age structured epidemic system and its application to the asymptomatic transmission model. Math Biosci. 2008;216:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichner M, Dowell SF, Firese N. Incubation period of Ebola hemorrhagic virus subtype Zaire. Osong Public Health Res Persptect. 2011;2:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowling BJ, Ip DK, Fang VJ, Suntarattiwong P, Olsen SJ, Levy J, et al. Aerosol transmission is an important mode of influenza A virus spread. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1935. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyfitz BL, Keyfitz N. The McKendrick partial differential equation and its uses in epidemiology and population study. Math Comp Model. 1997;26:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7177(97)00165-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallinga J, Lipsitch M. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B. 2007;274:599–604. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts MG, Heesterbeek JA. Model-consistent estimation of the basic reproduction number from the incidence of an emerging infection. J Math Biol. 2007;55:803–816. doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0112-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eichner M, Dietz K. Transmission potential of smallpox: estimates based on detailed data from an outbreak. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:110–117. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]