Abstract

Objective

To capture users’ experiences with a newly implemented electronic medical record (EMR) in family medicine academic teaching clinics and to explore their perceptions of its use in clinical and teaching processes.

Design

Qualitative study using focus group discussions guided by semistructured questions.

Setting

Three family medicine academic teaching clinics in Winnipeg, Man.

Participants

Faculty, residents, and support staff.

Methods

Focus group discussions were audiorecorded and transcribed. Data were analyzed by open coding, followed by development of consensus on a final coding strategy. We used this to independently code the data and analyze them to identify salient events and emergent themes.

Main findings

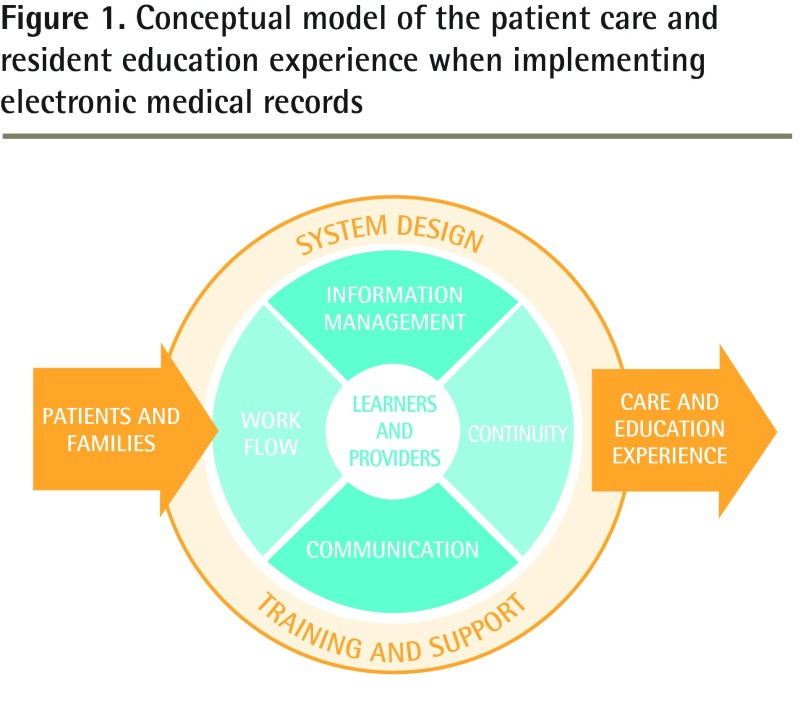

We developed a conceptual model to reflect and summarize key themes that we identified from participant comments regarding EMR implementation and use in an academic setting. These included training and support, system design, information management, work flow, communication, and continuity.

Conclusion

This is the first specific analysis of user experience with a newly implemented EMR in urban family medicine teaching clinics in Canada. The experiences of our participants with EMR implementation were similar to those reported in earlier investigations, but highlight organizational influences and integration strategies. Learning how to use and transitioning to EMRs has implications for clinical learners. This points to the need for further research to gain a more in-depth understanding of the effects of EMRs on the learning environment.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer l’expérience qu’ont les utilisateurs des dossiers médicaux électroniques (DME) récemment implantés dans des cliniques universitaires de médecine familiale, et vérifier ce qu’ils pensent de leur utilisation dans un contexte de soins et d’enseignement.

Type d’étude

Étude qualitative à l’aide de groupes de discussion utilisant des questions semi-structurées comme guides.

Contexte

Trois cliniques universitaires de médecine familiale de Winnipeg, au Manitoba.

Participants

Professeurs, résidents et membres du personnel.

Méthode

Les délibérations des groupes ont été enregistrées et transcrites. Les données ont été analysées par codage ouvert, après quoi un consensus a été développé grâce à une stratégie de codage finale. Cela a servi à coder les données de façon indépendante et à les analyser pour en extraire les éléments pertinents et les thèmes émergents.

Principales observations

Nous avons développé un modèle théorique qui tient compte des thèmes clés identifiés à partir des commentaires des participants à propos de l’introduction des DME et de leur utilisation dans un contexte académique, et qui les résume. Parmi ces thèmes, mentionnons la formation et le soutien nécessaires, le type de système, la gestion de l’information, le déroulement des opérations, les communications et la continuité.

Conclusion

Il s’agit de la première analyse spécifique de l’expérience qu’ont les utilisateurs des DME récemment introduits dans des cliniques universitaires urbaines de médecine familiale au Canada. L’expérience vécue par nos participants lors de l’introduction des DME était semblable à ce qu’ont rapporté des études antérieures, mais elle révèle l’existence d’influences organisationnelles et de stratégies d’intégration. Le fait de passer au DME et d’apprendre à se servir de ces dossiers a des conséquences pour les étudiants. Il semble donc que des études additionnelles seront nécessaires pour mieux comprendre les effets des DME dans un milieu d’apprentissage.

Electronic medical records (EMRs) propose to enhance the quality of care1,2 and, in spite of limited evidence of a positive effect on patient care,3 they are being widely implemented. Previous studies have examined factors affecting EMR implementation and adoption in ambulatory care settings,2 revealing several issues. Initial implementation challenges include reduced productivity, which might contribute to or result in resistance to the EMR.4 Implementation leads to changes in processes associated with documentation, managing laboratory results, and communication between providers and with patients.2 These changes have effects on individual EMR users, on the provider-patient interface, at the clinic level, and, depending on the setting, at the system level as well.

The literature addressing the experiences and challenges health care providers encounter during EMR implementation is expanding, but there is a paucity of qualitative research around users’ experiences and little research on the effects of EMR implementation on resident training. One study focusing on EMR use by residents found there was ambivalence among residents regarding the benefits of an EMR and frustration related to its usability. Residents in that study suggested EMRs did not generally increase the efficiency of patient care and held conflicting views on the effects of EMRs on patient-provider interactions.5

The objective of our study was to capture users’ experiences shortly after EMR implementation in family medicine academic teaching clinics, exploring perceptions of the role of the EMR in clinical and teaching processes. We hope this will inform users about how to leverage EMRs in both clinical and academic settings and contribute to a better understanding of how technology changes affect these environments.

METHODS

This is a qualitative study exploring users’ experiences with a newly implemented EMR. Three focus group discussions with physicians, allied health faculty, and residents were guided by semistructured, open-ended questions. Participants were asked about their overall experience with the EMR, its ease of use, the implementation process, and any effects the EMR might have had on clinical care and teaching. Audiorecorded discussions were transcribed by a medical transcriptionist. Data were analyzed by 3 members of the research team (G.H., A.S., C.S.) to identify salient events and common themes. First, we individually applied open coding to the data. We developed the final coding strategy through discussion and consensus, and each investigator independently applied it to the data set. Two of the team members (A.S., C.S.) were part of the Department of Family Medicine EMR Implementation Committee; however, to control for any potential biases in the analyses, a comparison of excerpts of coded data was performed and consensus was achieved through multiple iterations of coding and discussion.

FINDINGS

The focus groups were held at 3 teaching clinics; 2 had implemented the EMR 6 months before the study, and the third had implemented the EMR 12 months before the study. A total of 9 physicians (including the medical directors at all 3 clinics), 11 allied health faculty, and 8 family medicine residents attended the focus groups. Analysis of participants’ comments regarding their experiences with implementing and using the EMR in an academic primary care setting revealed the following themes: training and support, system design, information management, work flow, communication, and continuity. Work flow encompasses those processes associated with the work being done in the teaching clinics, specifically clinical care and education. This category contained the largest amount of data and was split into several subcategories: clinical processes, workarounds (defined as alternate work flows used to get through a task), time, scope, and teaching. An overview and summary of the details raised by participants in each of these domains is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary of focus group comments after EMR implementation

| DOMAIN | THEMES | SAMPLE QUOTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Training and support |

|

|

| System design |

|

|

| Information management |

|

|

| Communication |

|

|

| Continuity |

|

|

EMR—electronic medical record, ICD—International Classification of Diseases, IT—information technology.

Table 2.

Summary of focus group comments regarding EMR work flow

| WORK FLOW SUBDOMAIN | THEMES | SAMPLE QUOTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical processes |

|

|

| Workarounds |

|

|

| Time |

|

|

| Scope |

|

|

| Teaching |

|

|

EMR—electronic medical record.

DISCUSSION

Our focus groups primarily explored the effects of a newly implemented EMR in the academic family medicine clinic setting. We developed a conceptual model to reflect and summarize our findings. The interconnectedness of themes suggests there is a dynamic and complex process for EMR use, bearing similarity to Lau and colleagues’ Clinical Adoption Framework.3 Our 2-dimensional model of the patient care and resident education experience (Figure 1) represents the ecosystem through which patients and learners travel.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the patient care and resident education experience when implementing electronic medical records

Outer ring: infrastructure

Infrastructure represents EMR system design, performance, and training and support. The importance of the EMR interface design (eg, multiple screens, options) to minimize navigational challenges, the system’s reliability, and the effects of challenges associated with technical issues were themes repeated in our study and others.3,6,7 It is well known that lack of attention to EMR design to support practice and work flow influences EMR adoption. This suggests the need to bring health care providers into the design and implementation phase.8 Greater consideration of unique system design needs within clinics where learners are present might be warranted.

Patient care needs and routines drive EMR use, and users want to be able to employ the EMR within established clinical routines.9,10 We found that diverse and tailored training approaches are needed,9,11 as is sufficient time for incremental implementation, findings consistent with other studies.12 Additional consideration must be given to support once the EMR has been implemented. Reliance on hallway consultations and an “in-house problem solver”12 for immediate and ongoing hands-on support9 is reflected across studies. Lack of support contributes to persistent uncertainty, affecting the extent and consistency of EMR use.9,11,13 This might contribute to use of workarounds, such as those mentioned by our respondents. Using the EMR to profile users according to their use of EMR functions has been suggested as a means of identifying learning needs and issues.11 This approach might offer more immediate formative feedback around EMR use for learners in academic clinical settings.

Inner ring: interface and usage

The domains in the central portion of the model represent the EMR interface and usage underlying patient care and resident education. Information management is a primary function of the EMR, yet interface design was consistently mentioned as a concern. For example, the rigidity of storage and retrieval of patient information caused frustration as users found the EMR cumbersome and often not intuitive. Data standardization vis-à-vis autonomy has been considered by a number of other studies.7 Our study identified the potential of standardized data for more comprehensive patient reporting to benefit clinic management, consistent with findings from Kalra et al.14 The decision support functionality was rarely used by our respondents. However, participants who were familiar with the decision support features expressed concern about their effect on resident education and suggested a need for more functional tools to align with their work flow.

Time was an important theme in our study, and inadequate time was one of the most frequently cited implementation issues.7,9,11 Respondents struggled to maintain their usual teaching, which they attributed to the extra time it took to use the EMR. Similarly, Spencer et al15 found that faculty identified EMR implementation as a distraction from teaching, resulting in less time spent teaching. However, contrary to our study findings, Spencer et al15 reported that most of their respondents did not believe the EMR offered advantages for teaching. Respondents in both our study and that of Spencer et al15 noted there was an emphasis on getting information in or out of the EMR. Our respondents suggested a need for further supports to optimize use, rather than struggling with EMR functions, such as information retrieval, in order to simply complete a task.

Physicians report spending more time documenting and less time interacting with colleagues and patients after implementation of EMRs.16 The clerical nature of data entry expands the scope of tasks within each patient encounter,9 a task previously facilitated by transcriptionists in both our study and that of Embi and colleagues.16 A shift in task-related roles and responsibilities might lead to role ambiguity and conflict, although few studies have explored this issue.3

Faculty expressed concern about sharing EMR-based documentation tools such as macros and templates with learners. They thought these might affect the quality of clinical notes and the presentation of information, detracting from clinical reasoning, and could limit their ability to assess the critical-thinking skills of the learner. These issues have also been raised in previous reports,8,15,16 with the suggestion that such tools need to be considered more advanced functions.16 Ideal design and use of these functions in academic settings should be determined and prioritized by educators. This warrants further study.

The EMR became an additional party to the encounter, affecting the provider-patient interaction. The volume of patient information can draw the provider toward the EMR, particularly in the initial phases of implementation. Our respondents reported that searching for information took away from the encounter, and they sometimes needed to stop using the EMR during an interaction. A review6 found that few researchers have considered EMR interference in the patient-provider interaction. In another study, 92% of physicians reported that the EMR interfered with patient interactions, as they had to turn from the patient and to the computer to document the encounter. This is relevant for educators in an EMR-supported environment, and the implications for teaching need to be evaluated.

Some of our participants noted it was challenging to distinguish the appropriate scope of a visit. Effective management of a patient visit required increased attention to effective information filtering. The EMR provides an additional challenge in this regard owing to the increased volume and depth of information and less-linear format than paper charts. This adds more complexity for residents, who are learning to critically manage visit-relevant information and build competency in establishing rapport with patients.

Digital documentation was a substantial benefit to “real-time” observation of residents, as faculty could review the chart at the same time as the resident was seeing the patient. This was highlighted as a key benefit of the EMR to teaching work flow by our study respondents and is supported by previous findings.16 Simultaneous documentation and review served to decrease the time required for postencounter debriefs and the resident’s verbal explanation of diagnostic and clinical reasoning. For some, the unfortunate side effect was fewer interactions and opportunities for “teachable” moments.15 However, the improved availability of documentation augments the overall capacity of educators to oversee, monitor, and provide formative evaluation of the patient care provided by residents.16

A final consideration related to both information (documentation) and work flow is continuity. The benefit of information availability and the EMR functions for planning and follow-up care cited by our respondents have been reiterated by Embi et al,16 who found that these functions for enhanced continuity had some of the most profound effects on both clinical and educational activities.

Implications

Integrating the EMR into the clinical environment adds complexity to teaching medical learners. The EMR’s effect on clinical education must be recognized, and implementation strategies must be developed to address individual needs.10 As noted by Peled et al,17 it is time to consider the EMR’s role within the academic setting and not simply expect that it will intuitively be used as a practice and teaching tool. Strategies for implementation and use of new technology, particularly in academic settings, need to consider communication, documentation, clinical reasoning, and supervisory processes to ensure that the technology enhances clinical practice and education.8,17

As digital medical records become more commonplace in health care, these systems must be able to recognize the provider-learner-patient triad. Our study points to gaps in the ability to facilitate teaching with an EMR designed for the typical patient-provider interaction. Further, as distributed medical education becomes more common, tools required by those supervising learners will need to be identified and developed.

Limitations

Data were collected from 3 clinical training sites within a single resident training program at a single university, and within the context of a centrally managed, multisite, shared regional EMR database. The findings might not be entirely generalizable beyond the organizations and settings involved. However, many of the themes described in our study reflected those found in the literature on EMR adoption and implementation. Our focus groups were conducted at 2 points in time to collect a range of experiences rather than to compare the findings between the 2 groups (6 months and 12 months after implementation). Lau et al3 have suggested there is a need to measure the effects of postadoption usage over time in order to understand the various stages of user maturity; however, the findings presented here are intended to provide a snapshot of the users’ experiences early after the EMR was implemented and during the transition period.

Conclusion

This study explored users’ experiences with a newly implemented EMR in family medicine academic teaching clinics. Findings generated a conceptual model of patient care and resident education experiences. The model reflects how learners and providers are directly affected by EMR interface and usage issues (information management, clinic work flow, communication, and continuity), which is further influenced by EMR design, performance, and training and support. While we found the effects of EMR implementation in the academic setting were consistent with those identified in previous research, our findings support the need for future research directed at better understanding how EMRs affect the learning environment. In particular, further exploration is necessary around the needs of educators and learners, and how to use tools to facilitate decision support, communication, and supervision. To our knowledge, this is the first specific analysis of an EMR’s effects on urban academic family medicine clinics in Canada. While recognizing that behaviour change related to EMR use is modifiable over time, early usage experiences are continuously encountered in the teaching setting. Further, explicating these experiences provides a better understanding of how technology can affect clinical teaching, supervision, and practice and influences ways in which EMRs can be further tailored to the needs of clinicians at all stages of use.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Electronic medical records (EMRs) propose to enhance the quality of patient care and they are being widely implemented. This qualitative study explored users’ experiences with a newly implemented EMR in family medicine academic teaching clinics, and examined how the EMR affected not only patient care but also the learning and teaching process.

Both benefits and limitations of the EMR were identified for teaching and patient care. Some of the greatest benefits were noted for continuity of care and learner assessment; however, the EMR also added complexity that could not be intuitively or easily overcome. Implementation strategies and functions specific to the training environment need to be further explored.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les dossiers médicaux électroniques (DME) ont pour but d’améliorer la qualité des soins aux patients et ils sont de plus en plus utilisés. Cette étude qualitative voulait connaître l’expérience des utilisateurs des DME nouvellement introduits dans des cliniques universitaires de médecine familiale et vérifier comment le DME affectait non seulement les soins aux patients mais aussi les processus d’apprentissage et d’enseignement.

On a identifié des avantages et des inconvénients à l’utilisation des DME, tant pour l’enseignement que pour les soins aux patients. Parmi les avantages les plus importants, mentionnons la continuité des soins et l’évaluation des étudiants; toutefois, le DME ajoutait une complexité qu’on ne pouvait pas résoudre intuitivement ni facilement. Les stratégies d’implantation et les fonctions propres à un milieu d’apprentissage devront être davantage étudiées.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Crosson JC, Stroebel C, Scott JG, Stello B, Crabtree BF. Implementing an electronic medical record in a family medicine practice: communication, decision making, and conflict. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):307–11. doi: 10.1370/afm.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwick D, Manca D, Doucette J. Primary care physicians’ experiences with electronic medical records. Implementation experience in community, urban, hospital, and academic family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(1):40–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau F, Price M, Boyd J, Partridge C, Bell H, Raworth R. Impact of electronic medical record on physician practice in office settings: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott JT, Rundall TG, Vogt TM, Hsu J. Kaiser Permanente’s experience of implementing an electronic medical record: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2005;331(7528):1313–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38638.497477.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaronson JW, Murphy-Cullen CL, Chop WM, Frey RD. Electronic medical records: the family practice resident perspective. Fam Med. 2001;33(2):128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boonstra A, Broekhuis M. Barriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGinn CA, Grenier S, Duplantie J, Shaw N, Sicotte C, Mathieu L, et al. Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammoud MM, Dalymple JL, Christner JG, Stewart RA, Fisher J, Margo K, et al. Medical student documentation in electronic health records: a collaborative statement from the alliance for clinical education. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(3):257–66. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.692284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetz Goldberg D, Kuzel AJ, Feng LB, DeShazo JP, Love LE. EHRs in primary care practices: benefits, challenges, and successful strategies. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(2):e48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vedel I, Lapointe L, Lussier M, Richard C, Goudreau J, Lalonde L, et al. Healthcare professionals’ adoption and use of a clinical information system (CIS) in primary care: insights from the Da Vinci study. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(2):73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo VH, Martínez-García AI, Pulido J. A knowledge-based taxonomy of critical factors for adopting electronic health record systems by physicians: a systematic literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terry AL, Giles G, Brown JB, Thind A, Stewart M. Adoption of electronic medical records in family practice: the providers’ perspective. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):508–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price M, Singer A, Kim J. Adopting electronic medical records. Are they just electronic paper records? Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(7):e322–9. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/59/7/e322.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2015 Apr 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalra D, Fernando B, Morrison Z, Sheikh A. A review of the empirical evidence of the value of structuring and coding of clinical information within electronic health records for direct patient care. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20(3):171–80. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v20i3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer DC, Choi D, English C, Girard D. The effects of electronic health record implementation on medical student educators. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(2):106–10. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.664513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Embi PJ, Yackel TR, Logan JR, Bowen JL, Cooney TG, Gorman PN. Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(4):300–9. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peled JU, Sagher O, Morrow JB, Dobbie AE. Do electronic health records help or hinder medical education? PLoS Med. 2009;6(5):e1000069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]