Abstract

Background

Oblique facial clefts, also known as Tessier clefts, are severe orofacial clefts, the genetic basis of which is poorly understood. Human genetics studies revealed that disruption in SPECC1L resulted in oblique facial clefts, demonstrating that oblique facial cleft malformation has a genetic basis. An important step toward innovation in treatment of oblique facial clefts would be improved understanding of its genetic pathogenesis. The authors exploit the zebrafish model to elucidate the function of SPECC1L by studying its homolog, specc1lb.

Methods

Gene and protein expression analysis was carried out by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry staining. Morpholino knockdown, mRNA rescue, lineage tracing and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assays were performed for functional analysis.

Results

Expression of specc1lb was detected in epithelia juxtaposed to chondrocytes. Knockdown of specc1lb resulted in bilateral clefts between median and lateral elements of the ethmoid plate, structures analogous to the frontonasal process and the paired maxillary processes. Lineage tracing analysis revealed that cranial neural crest cells contributing to the frontonasal prominence failed to integrate with the maxillary prominence populations. Cells contributing to lower jaw structures were able to migrate to their destined pharyngeal segment but failed to converge to form mandibular elements.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that specc1lb is required for integration of frontonasal and maxillary elements and convergence of mandibular prominences. The authors confirm the role of SPECC1L in orofacial cleft pathogenesis in the first animal model of Tessier cleft, providing morphogenetic insight into the mechanisms of normal craniofacial development and oblique facial cleft pathogenesis.

Orofacial clefts are among the most common congenital malformations, with a prevalence of one in 700 to one in 1000 births.1,2 Orofacial clefts range from the common cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate only, to rare and complex oblique facial clefts, also known as Tessier clefts.3–6 Although surgical management of cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate only are routine, and good functional and cosmetic results can be achieved, repair of oblique facial clefts is generally difficult, with more modest surgical results.7,8 Affected children require multiple staged surgical procedures in early childhood and need lifelong multidisciplinary treatment with significant financial burden to their families and the health care system.9 Better understanding of the genetic basis of palate and cleft formation would aid genetic diagnosis of orofacial clefts and lead to potential advances in the treatment of these common structural malformations.10–12

Many genetic loci associated with cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate only have been described, such as MSX1, IRF6, SUMO1, an TGFB.5,13–19 In contrast to the common cleft lip with or without cleft palate, little is known about the genetic basis of oblique facial clefts. For lack of better understanding, clinicians have suggested that oblique facial clefts may be caused by a combination of directly tethered tissue disrupting facial prominence migration (such as amniotic bands) or increased local pressure that causes ischemia.20 It was not until this work that we begin to show that oblique facial clefts, like the more common cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate only, has a genetic basis, through the discovery of mutations in SPECC1L to be causal for oblique facial clefts.21

SPECC1L encodes a novel coiled-coil domain containing protein and functionally interacts with both microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton, especially in mitotic spindles.21 In a wound-repair assay, SPECC1L knockdown led to defective cell adhesion and migration and inability of cells to reorganize their actin cytoskeleton in response to stimuli such as Ca2+ and Wnt5a. Morpholino-based knockdown of SPECC1L homologs in zebra-fish led to a “faceless” phenotype. This work did not describe the craniofacial structures in detail, which precluded evaluation of the mandible and palate. Disruption in Drosophila led to cell migration and adhesion defects resulting in a wide range of wing phenotypes.21 The wing phenotypes observed in SPECC1L knockdown experiments in Drosophila had a striking resemblance to mutants in the integrin signaling pathway,22 suggesting that SPECC1L may be involved in integrin-mediated cell motility and adhesion. However, the means by which SPECC1L participates in integrin and WNT pathways during craniofacial development remains undefined. The function of SPECC1L in craniofacial morphogenesis is also unknown.

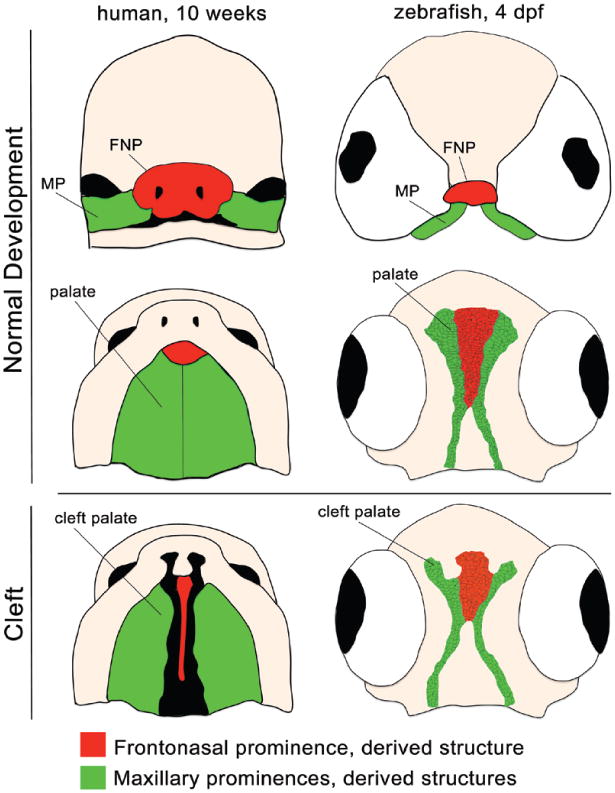

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a powerful genetic tool for study of the developmental and genetic basis of orofacial clefts. Many features of zebra-fish biology, including small size, rapid and ex vivo embryonic development, and high breeding rates, make this model system very useful. The embryos are optically transparent and genetically tractable, and can be used in large-scale genetic and chemical screens. We and others described the conservation of palatogenic gene expression and function across vertebrates.23–26 It was also shown that zebrafish cranial neural crest cells reside in analogous regions of the developing face compared with amniote species, and that the zebrafish palate is analogous to the amniote primary palate (Fig. 1). In addition to structural similarities between zebrafish and mammalian craniofacial development, the gene regulatory network is highly conserved with genes such as WNT signaling, sonic hedgehog, fibroblast growth factor 8, transcription factor AP-2a, and PDGFRA all playing key roles.27–31 Furthermore, we demonstrated that the pathogenesis of orofacial cleft is also conserved between amniotes and zebrafish, where disruption of wnt9a and irf6, which are important mutations associated with human cleft lip with or without cleft palate, also resulted in zebrafish cleft palate phenotypes.23 Recent innovations in gene editing and knockout approaches using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and transcription activator-like effector nucleases have further advanced zebrafish as a first-line model system of choice to analyze genes of unknown function uncovered from human genetics studies.32–35

Fig. 1.

Human embryo at 10 weeks (left) and zebrafish embryo at 4 days post fertilization (dpf) (right), at analogous developmental time points. Frontal (above) and palatal views (center and below) of the frontonasal prominence (FNP; red) and maxillary prominences (MP; green) and their derivative structures demonstrate conservation of normal palate development (above and center) and cleft pathogenesis (below).

This work aimed to elucidate the function of SPECC1L through the study of its homolog, specc1lb, in the zebrafish model. In zebrafish, we can readily determine the embryonic gene expression of specc1lb, assess the functional requirement of specc1lb during craniofacial morphogenesis, and study the cellular mechanisms where specc1lb acts. This study forms the basis for future functional analysis of SPECC1L, such as gene targeting in murine models or to guide future biochemical approaches.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish Lines and Maintenance

All embryos and fish were raised and cared for using established protocols according to the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, Massachusetts General Hospital.36

Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis

SPECC1L homologs were identified in the zebrafish genome using the human SPECC1L mRNA sequence and protein sequences, respectively (National Center for Biotechnology Information: NM_001254733.1, NP_056145), in the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST tool. Zebrafish genes with the greatest sequence homology are annotated as specc1la and specc1lb (National Center for Biotechnology Information: specc1la, NM_001039816; specc1lb, XM_677967). The specc1la and specc1lb cDNAs were cloned by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) from cDNA prepared from embryos at 48 hours post fertilization and subcloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). Sequence analysis and alignment were performed with BioEdit 7.1.9 (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, Calif.) and Lasergene 9.0 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) program suites, using the CLUSTAL W alignment algorithm.

Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was isolated from whole embryo lysates and converted to cDNA using iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Primers were designed using the A plasmid Editor sequence editing software (Primer design tool) to amplify from the cDNA library by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (Phusion RT PCR kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, Mass.). ef1α was used as a positive control. It is ubiquitously expressed across all embryonic time points.37

Immunohistochemistry

Antisera against zebrafish specc1lb (anti-specc1lb peptide, 795-RKQDEERGRVYN-806, affinity-purified, Pierce custom services; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for immunohistochemical staining. Transverse sections of zebrafish embryos 4 days post fertilization were blocked in 5% normal goat serum, 2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 hour, and then incubated in serum containing polyclonal antibodies against specc1lb or preimmunized serum. The serum was diluted 1:200 in phosphate-buffered saline and contained 2% bovine serum albumin to block nonspecific binding. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20, the second antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen) (diluted 1:1000 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin) was applied to the samples for 30 minutes. The samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and examined using fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, N.Y.).

Morpholino and RNA injection

Translation-blocking specc1la and specc1lb morpholinos and mismatch control morpholinos were designed by Gene Tools (Philomath, Ore.) with the following nucleotide sequences: 5′-CCACTGGCCTGCCTGCTTTCTTCAT-3′ (for specc1la morpholinos), 5′-ACTATGGTTTTGCTTGGAGGCCGTT-3′ (for specc1lb morpholino), 5′-CCACAGCCCAGCCTCCTTTGATCAT-3′ (for specc1la mismatch control morpholinos), and 5′-ACAATCGTTTTCCTTGCACGCCGTT-3′ (for specc1lb mis-match control morpholinos). Mismatch control morpholinos have the same sequence as the real morpholinos, but five nucleotides do not match. This morpholino should not have an effect on the embryo and serves as an optimal control.38 For the morpholinos and mismatch control morpholinos, the 1-mM stock solution was diluted to 0.080 mM with UltraPure DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). Then, 0.5 nl of the solution was injected into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos with borosilicate glass needles (outside diameter, 1.0 mm; inside diameter, 0.50 mm; Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, Calif.) pulled with a Flaming/Brown Micropipette Puller, Model P-97 using a PLI-90A Pico-Liter Injector (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Mass.). The phenotype was assessed with Alcian blue staining at 5 days post fertilization.39 The specc1la morpholino did not produce a phenotype, even at high concentrations. We screened embryos for toxicity 24 hours post fertilization, which was below 10 percent, and such embryos were excluded from analysis. Screening for neural toxicity was performed because some morpholinos induce non–target-related toxic phenotypes apparent as cell death in the central nervous system.40,41 Capped full-length specc1lb mRNAs were synthesized from pCS7:specc1lb (Addgene, Cambridge, Mass.) using Sp6 mMessage mMachine kit (Life Technologies). For rescue experiments, embryos were injected first with morpholino or mismatch control morpholinos; then, half of these embryos were injected with mRNA (0.5 nl of 125-ng/μl solution).

Cartilage Staining

Alcian blue staining was performed to analyze the craniofacial skeleton, and images were obtained using a Nikon 80i compound microscope.42,43

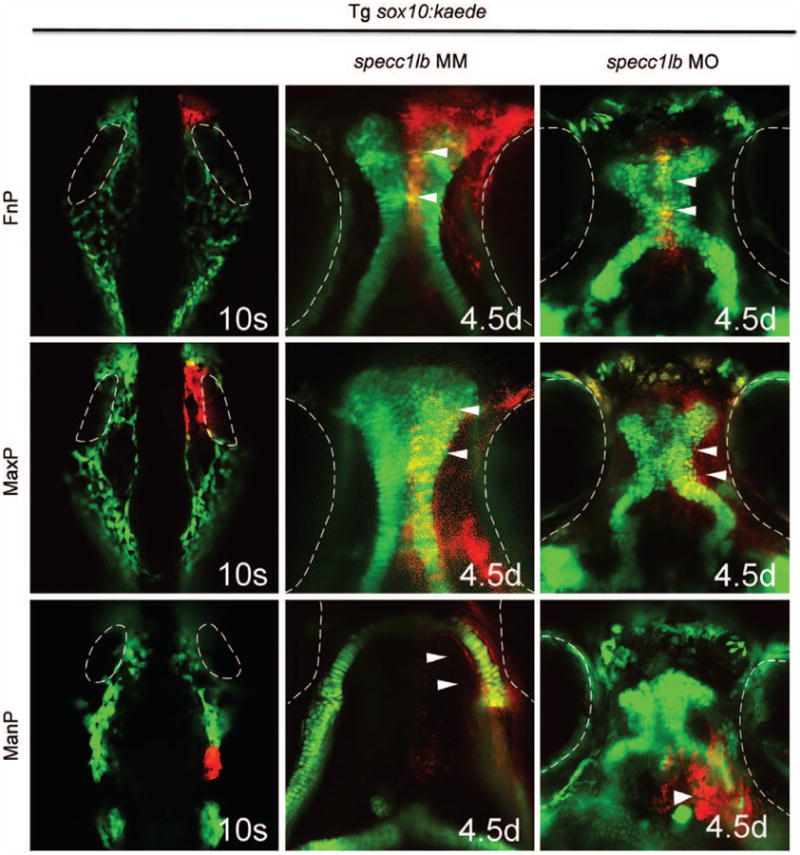

Lineage Analysis and Imaging

Tg sox10:kaede was used to perform lineage tracing analysis; sox10 is a neural crest cell marker. Kaede can be photoconverted from green to red by exposure to ultraviolet light, which allows specific groups of cranial neural crest cells to be labeled. Photoconversion was performed unilaterally in specc1lb mismatch control morpholinos and specc1lb morpholino knockdown sox10:kaede embryos at the 10-somite stage using ultraviolet light (404.3 nm). The contralateral side served as an internal control.44 Embryos were raised until 4.5 days post fertilization and imaged on the confocal microscope (Nikon A1R Si Confocal Ti series).

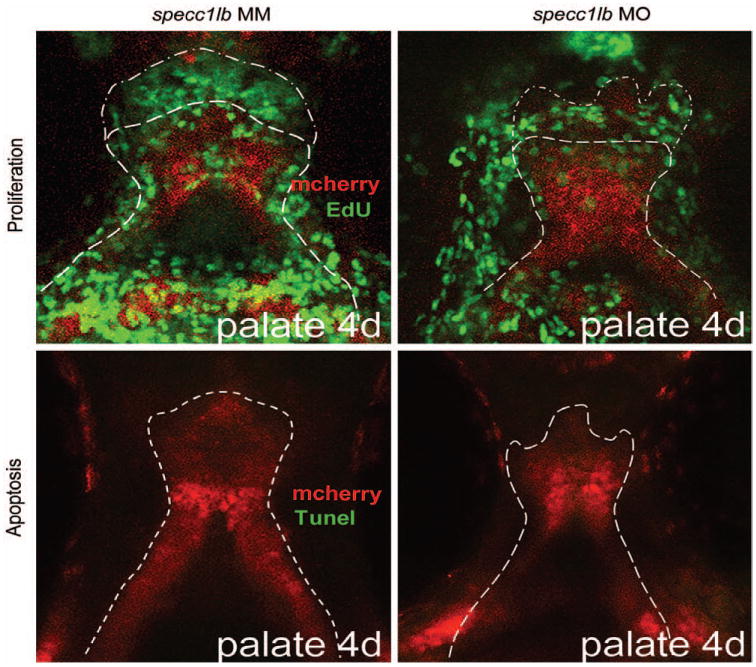

Proliferation and Apoptosis Assays

Proliferation was detected using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen). Apoptosis was detected using the Click-iT TUNEL Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Assay (Invitrogen). Detection was performed in the background of a sox10:mcherry transgenic line, so that proliferation of cranial neural crest–derived chondrocytes could be tracked (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine in green will co-localize with mcherry reporter protein in red).

Results

Conservation and Gene Expression of SPECC1L Zebrafish Homologs specc1la and specc1lb

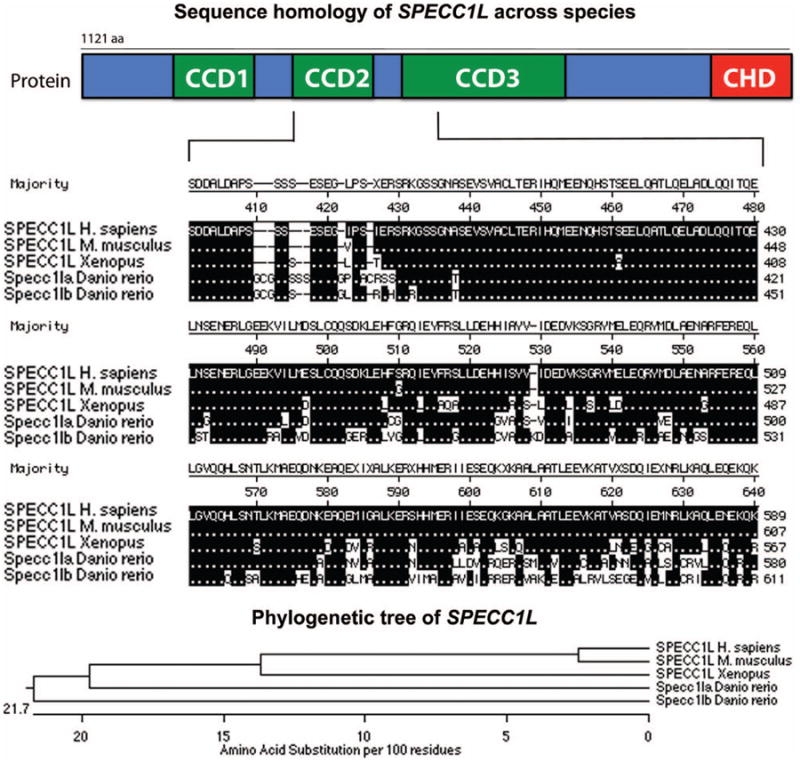

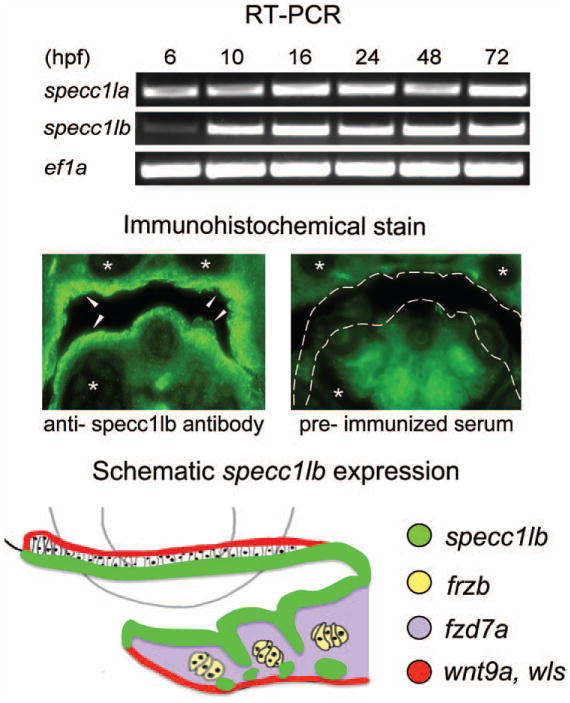

The zebrafish genome contains two homologs of the human SPECC1L gene: specc1la (chromosome 8) and specc1lb (chromosome 21).45 Structurally, human SPECC1L protein contains three coiled-coil domains and one calponin homology domain (Fig. 2, above). Peptide alignment showed that these domains are highly conserved across vertebrate species, including mouse, chick, Xenopus, and zebrafish (Fig. 2, center and below). Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis reveals that the SPECC1L ortholog specc1lb is expressed as early as 6 hours post fertilization and expression persists until 3 to 4 days post fertilization (Fig. 3, above). To determine the craniofacial expression of SPECC1L homologs, immunohistochemical staining of sections with an antibody specific to a conserved domain shared between specc1la and specc1lb proteins was carried out, demonstrating specific localization of specc1la/b to the oropharyngeal epithelia and exclusion from chondrocytes of the upper and lower jaw structures (Fig. 3, center and below). Immunohistochemical staining with preimmunized serum control did not demonstrate specific signal (Fig. 3, center, right).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of SPECC1L protein structure (above). SPECC1L protein alignment highlights conservation across vertebrates (center). Phylogenetic relationship of SPECC1L across vertebrate species (below).

Fig. 3.

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis shows specc1la and specc1lb expression up to day 3 and beyond (data not shown); ef1α was used as a control (above). Immunohistochemical staining detects specc1lb protein in the oropharyngeal epithelia (arrows) but not in the chondrocytes (asterisks) (center, left). Staining with preimmunized serum was used as a negative control (center, right). Diagram of specc1lb (green), frzb (yellow), fzd7a (violet), wnt9a (red), and wls (red) expression in the oropharyngeal region (below). hpf, hours post fertilization.

Loss of specc1lb Function Results in Upper and Lower Jaw Defects

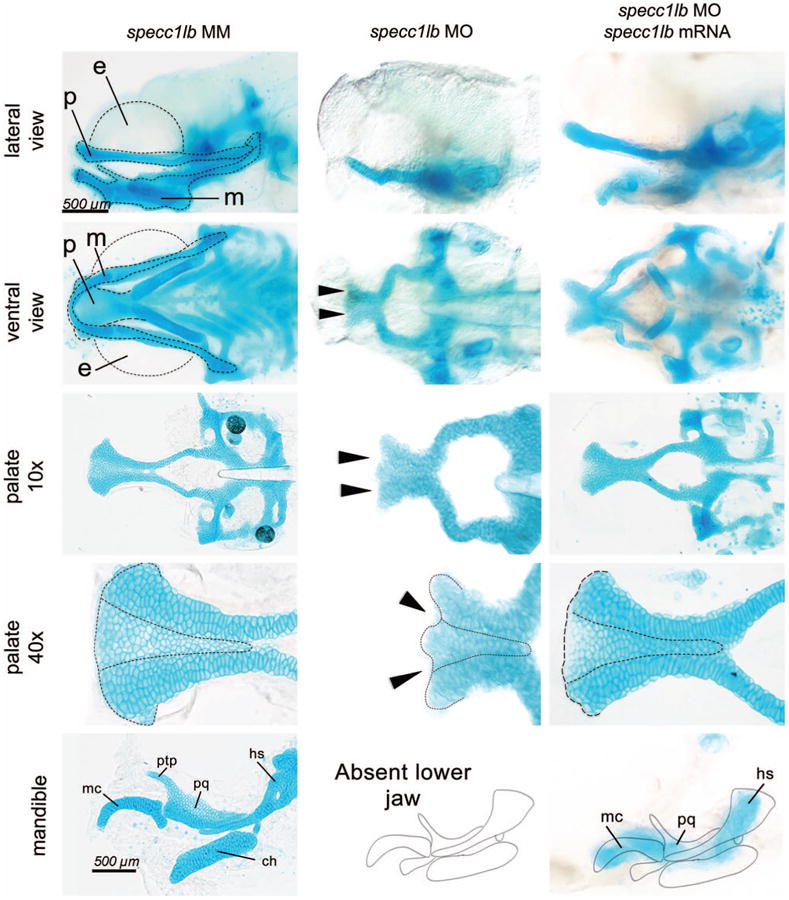

To assess functional requirements of specc1la and specc1lb during craniofacial development and cleft pathogenesis, gene disruption was mediated by morpholino knockdown. Although specc1la morpholino failed to produce a craniofacial phenotype, specc1lb gene disruption produced a distinct craniofacial malformation affecting both the upper and lower jaw elements. (See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which demonstrates cleft development in specc1lb morpholino knockdown morphant. Live time-lapse recording of developing ethmoid plate in a specc1lb morpholino knockdown Tg sox10:kaede zebrafish embryo (ventral view) at 60 hours post fertilization; sox10 provides lineage restriction of the kaede reporter protein to the neural crest. Failure of fusion between median ethmoid plate cells and lateral ethmoid plate cells can be observed. The video was recorded every 30 minutes starting 60 to 72 hours post fertilization, http://links.lww.com/PRS/B96.) Further analysis was carried out with specc1lb only, as specc1lb was found to be the functional ortholog of human SPECC1L displaying a knockdown phenotype. The upper jaw phenotype exhibited bilateral clefts between the median and lateral elements of the ethmoid plate, a zebrafish structure analogous to the primary palate in amniotes. Furthermore, the mandible was entirely absent (Fig. 1 and Fig. 4, center). The best view to appreciate the absent lower jaw is in Figure 4, above, center, which shows a clear palate on lateral view, but no lower jaw. To confirm specificity of the specc1lb knockdown phenotype, rescue experiments with full-length specc1lb mRNA were performed. Co-injection of nonhomologous specc1lb mRNA with specc1lb morpholino led to a partial rescue of the phenotype. The partially rescued phenotype consisted of a morphologically complete distal palate without clefts and rescue of lower jaw elements (Meckel's cartilage, palatoquadrate, and hyosymplectic) (Fig. 4, right).

Fig. 4.

Normal jaw structures are seen in control embryos (left). (Above and second row) The palate (p), mandible (m), and eyes (e) are surrounded by a dotted line. Jaw elements are labeled as the Meckel's cartilage (mc), palatoquadrate (pq), pterygoid process (ptp), ceratohyal (ch), and hyosymplectic (hs). Knockdown of specc1lb led to a shortened primary palate with bilateral clefts between the median and lateral elements of the primary palate (arrows, dotted line) and absence of lower jaw (center). Co-injection of specc1lb mRNA with specc1lb morpholino (MO) led to a partial rescue of the phenotype consisting of a primary palate without cleft (dotted line) and rescue of lower jaw elements (mc, pq, and hs) (below, right). MM, mismatch control morpholinos.

The specc1lb Phenotype Results from Failure of Integration between the Lateral and Median Primary Palate with Reduced Cell Proliferation

To elucidate cellular and morphogenetic mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of clefts and absent mandible in specc1lb morphants, lineage analysis of migrating cranial neural crest cells was performed. Using the Tg sox10:kaede transgenic line, cranial neural crest cells destined for frontonasal, maxillary, and mandibular prominences were labeled in specc1lb morphants and mismatch control morpholino–injected controls.46 In specc1lb mismatch control morpholino, cranial neural crest cells located anterior to the eyes at the 10-somite stage migrated to form the frontonasal prominence, which contributes to the median primary palate (Fig. 5, above, center). Cranial neural crest cells located medial to the eyes migrated to form the maxillary prominence, which contributes to the lateral element of the primary palate (Fig. 5, center, center). Finally, cranial neural crest cells located posterior to the eyes migrated to form the mandibular prominence (Fig. 5, below, center). Lineage tracing labeling experiments of cranial neural crest cells in specc1lb morphants showed that migration of cranial neural crest cells contributing to the facial prominences reached only the proper pharyngeal segment at 48 hours post fertilization, but failed to converge toward the midline and contribute to their respective facial prominence structures. More specifically, the anterior cranial neural crest cell population that normally would contribute to the frontonasal process and the more posterior cranial neural crest cell population that contributes to the maxillary prominence still migrated to their respective pharyngeal domains. However, subsequent morphogenesis of the facial form involving integration of the frontonasal and maxillary prominences with one another failed to occur, leading to clefts between the median and lateral palate elements (Fig. 5, above, right, and center, right). In addition, cells that normally contribute to the mandible reached the mandibular domain but failed to converge to the midline to form the lower jaw (Fig. 5, below, right).

Fig. 5.

Cranial neural crest cells located anterior to the eyes at the 10-somite stage (eyes outlined in white) migrate to form the middle part of the primary palate or the frontonasal prominence (above, left, and center). Cranial neural crest cells located medial to the eyes migrate to form the lateral part of the primary palate to the maxillary prominence (center, left, and center). Cranial neural crest cells located posterior to the eyes migrate to form the mandibular prominence (below, left, and center). In specc1lb morphants, cranial neural crest cells constituting the frontonasal prominence (above, right) (arrows) fail to fuse with cells constituting the maxillary prominence (center, right) (arrows). Cells that normally develop into a lower jaw fail to converge toward the midline and instead form ectopic structures beneath the eyes (below, right) (arrow).

The zebrafish palate forms by a process of convergence and extension to generate the cartilaginous framework, where palate extension is mediated by cell intercalation and proliferation of chondrocytes in the leading edge.47 Examination of cell proliferation and apoptosis using 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine labeling and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assay, respectively, reveal that the proliferative front forms but is reduced in specc1lb morphants compared with mismatch control morpholino controls (Fig. 6, above, right). In contrast, there is no difference in the degree of apoptosis between control and specc1lb morphants at 55 to 60 hours post fertilization (Fig. 6, below, right).

Fig. 6.

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining reveals a green proliferative front (dotted line) at the leading edge of the developing primary palate in specc1lb mismatch (MM) control embryos and in specc1lb morphants (MO) (above). A marked decrease in neural crest cell proliferation is noted (above, right). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assay for apoptosis shows that specc1lb phenotypes are not a result of increased cell death in the ethmoid plate region during extension (below, right).

Discussion

Orofacial clefts represent a diverse malformation spectrum, ranging from the common cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate only (one in 700 to one in 1000), to the rare and dramatic oblique facial clefts (one in 200,000).1,2 Until recent description of the SPECC1L mutation resulting in oblique facial clefts, no gene had been implicated in oblique facial clefts, and the pathogenesis of this malformation has been largely speculative.21 SPECC1L encodes a cytoskeletal protein, which in mammalian cell assays co-localizes with tubulin and actin, and its deficiency results in defective cell adhesion and migration.21 However, the role of SPECC1L in craniofacial development and oblique facial cleft pathogenesis remained to be elucidated.

This study examined the function of SPECC1L by studying its homologs in zebrafish, where specc1lb is the ortholog. Interestingly, specc1lb expression was found in oropharyngeal epithelia juxtaposed to chondrocytes, suggesting that these genes may be expressed in the endoderm surrounding neural crest cells and not in neural crest cells themselves. The pharyngeal epithelia can induce cartilage in mammals and may also play a patterning role, as it expresses extracellular signaling molecules (e.g., edn, wnt9a, fgf8, shh) involved in craniofacial development.48–52 SPECC1L disruption may alter expression of these molecules and inhibit normal chondrocyte formation.

specc1lb Is Required for Upper Jaw Integration and Lower Jaw Formation

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the specc1lb morphant phenotype, lineage-tracing analysis was performed and revealed that in specc1lb morphant embryos, cell migration to the corresponding pharyngeal segment occurred. However, cranial neural crest cells contributing to the frontonasal prominence fail to integrate or “fuse” with the maxillary prominence cranial neural crest cells, leading to clefts between median and lateral elements of the palate. This mechanism explains the pathogenesis of oblique facial cleft development in humans, where failure of fusion between the lateral nasal process (a derivative of frontonasal prominence and analogue of the median ethmoid plate in zebrafish) and maxillary prominence (analogous to the lateral ethmoid plate in zebrafish) occurs.53 In experiments performed by Saadi et al., knockdown in Drosophila leads to cell migration and adhesion defects that resemble integrin knockout phenotypes. In zebrafish, integrin knockdown leads to cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion defects in the basal epidermis.21 We posit that specc1lb may be involved in proper integration and adhesion of chondrocytes in the developing zebrafish palate, interacting with integrin and specc1lb, which are expressed in the ectoderm.

Cells normally contributing to the Meckel's cartilage were able to migrate to their destined facial prominence domains but failed to converge to form mandibular elements. This defect resembles the same phenotype observed when wnt9a, frzb, and fzd7a are depleted by morpholino, where the lower jaw is grossly absent and the directed migration of cranial neural crest cells to the mandibular arch is intact.23,47

As described by our group and others, the zebrafish palate is analogous to the amniote primary palate, formed by migration of cranial neural crest cells to the proper pharyngeal segment, convergence of facial prominences, and extension of the fused structures.23,24 Zebrafish palate morphogenesis can be described by distinct mechanisms: chondrocyte extension, proliferation, and integration, where wnt9a is required for palatal extension and proliferation and irf6 is required for integration of facial prominences along a V-shaped seam.23 In addition, frzb and fzd7a are dispensable for directed migration of the bilateral trabeculae, but are required for convergence of the mandibular prominences and for palate extension.47 We report failure of full extension of the developing primary palate, reduction of the proliferative front of cranial neural crest cells, and failure of integration or fusion of facial prominences in specc1lb knockdown morphants; specc1lb may be involved in this network of genes required for normal convergence of facial prominences and may interact with these genes to ensure correct extension and fusion of the palate. Because the specc1lb protein structure exhibits features of a scaffolding protein, its function may be to transduce molecular signals to morphologic change, a process important for inter-cellular integration. This function has precedence in β-spectrin, which serves as a scaffolding protein to stabilize transforming growth factor-β receptors and functions in regulating palatogenesis.54

Considered together, this analysis suggests that specc1lb is required for integration of upper jaw palatal elements and convergence of mandibular prominences. Biochemical experiments are underway to elucidate the cellular function and identify protein interactors of specc1lb. Germline specc1lb mutants are also being generated using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, to serve as the substrate for genetic and chemical screens, to identify signaling pathways regulated by specc1lb. Moreover, identification of chemical modifiers of specc1lb mutant phenotype may allow us to find small molecules to mitigate the cleft pathogenesis before its malformation. We present the first animal model of oblique facial clefts and morphogenetic insight into the mechanisms of oblique facial cleft.

Supplementary Material

Video. Supplemental Digital Content 1 demonstrates cleft development in specc1lb morpholino knockdown morphant. Live time-lapse recording of developing ethmoid plate in a specc1lb morpholino knockdown Tg sox10:kaede zebrafish embryo (ventral view) at 60 hours post fertilization; sox10 provides lineage restriction of the kaede reporter protein to the neural crest. Failure of fusion between median ethmoid plate cells and lateral ethmoid plate cells can be observed. The video was recorded every 30 minutes starting 60 to 72 hours post fertilization, http://links.lww.com/PRS/B96.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate support by the Shriners Hospital for Children (to E.C.L.), the March of Dimes Basil O'Connor Award (to E.C.L.), the Plastic Surgery Foundation, the Doctoral Fellowship Programme of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (to L.G.), a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Student Award (to V.S.), a Shriners Hospitals for Children Research Fellowship Award (to Y.K.), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant PO1GM061354 (to C.C.M.). They thank Renee Ethier for excellent care of their aquatics facility. Jenna Galloway and their laboratory colleagues provided valuable feedback and review of this article.

This work was supported by THE PLASTIC SURGERY FOUNDATION.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Simply type the URL address into any Web browser to access this content. Clickable links are provided in the full-text article on www.PRSJournal.com.

Presented at 35th Annual Meeting of the Society of Craniofacial Genetics and Developmental Biology, in San Francisco, California, November 6, 2012; the 54th Annual Meeting of the New England Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, in Newport, Rhode Island, May 31 through June 2, 2013; the 30th Annual Meeting of the Northeastern Society of Plastic Surgeons, in Washington, DC, September 20 through 22, 2013; and the 59th Annual Meeting of the Plastic Surgery Research Council, in New York, New York, March 7 through 9, 2014.

References

- 1.Tolarová MM, Cervenka J. Classification and birth prevalence of orofacial clefts. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:126–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genisca AE, Frias JL, Broussard CS, et al. Orofacial clefts in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2004. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149:1149–1158. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eppley BL, van Aalst JA, Robey A, Havlik RJ, Sadove AM. The spectrum of orofacial clefting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:101e–114e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000164494.45986.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson LF, Musgrave RH, Garrett W, Conklin JE. Reconstruction of oblique facial clefts. Cleft Palate J. 1972;9:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet. 2002;32:285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tessier P. Anatomical classification facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69–92. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(76)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Versnel SL, van den Elzen ME, Wolvius EB, et al. Long-term results after 40 years experience with treatment of rare facial clefts: Part 1. Oblique and paramedian clefts. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1334–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pidgeon TE, Flapper WJ, David DJ, Anderson PJ. From birth to maturity: Midline Tessier 0–14 craniofacial cleft patients who have completed protocol management at a single craniofacial unit. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014;51:e70–e79. doi: 10.1597/12-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deleyiannis FW, TeBockhorst S, Castro DA. The financial impact of multidisciplinary cleft care: An analysis of hospital revenue to advance program development. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:615–622. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31827c6ffb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levi B, Brugman S, Wong VW, Grova M, Longaker MT, Wan DC. Palatogenesis: Engineering, pathways and pathologies. Organogenesis. 2011;7:242–254. doi: 10.4161/org.7.4.17926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, Slater BJ, Kwan MD, Liu KJ, Longaker MT. Tissue engineering in cleft palate and other congenital malformations. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:545–551. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816a743e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren SM, Longaker MT. New directions in plastic surgery research. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangold E, Ludwig KU, Nöthen MM. Breakthroughs in the genetics of orofacial clefting. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkuraya FS, Saadi I, Lund JJ, Turbe-Doan A, Morton CC, Maas RL. SUMO1 haploinsufficiency leads to cleft lip and palate. Science. 2006;313:1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leslie EJ, Mancuso JL, Schutte BC, et al. Search for genetic modifiers of IRF6 and genotype-phenotype correlations in Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161:2535–2544. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leslie EJ, Standley J, Compton J, Bale S, Schutte BC, Murray JC. Comparative analysis of IRF6 variants in families with Van der Woude syndrome and popliteal pterygium syndrome using public whole-exome databases. Genet Med. 2013;15:338–344. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satokata I, Maas R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat Genet. 1994;6:348–356. doi: 10.1038/ng0494-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:769–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayou BJ, Fenton OM. Oblique facial clefts caused by amniotic bands. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:675–681. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saadi I, Alkuraya FS, Gisselbrecht SS, et al. Deficiency of the cytoskeletal protein SPECC1L leads to oblique facial clefting. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SB, Cho KS, Kim E, Chung J. blistery encodes Drosophila tensin protein and interacts with integrin and the JNK signaling pathway during wing development. Development. 2003;130:4001–4010. doi: 10.1242/dev.00595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty M, Kamel G, Grimaldi M, et al. Distinct requirements for wnt9a and irf6 in extension and integration mechanisms during zebrafish palate morphogenesis. Development. 2013;140:76–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.080473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swartz ME, Sheehan-Rooney K, Dixon MJ, Eberhart JK. Examination of a palatogenic gene program in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2204–2220. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberhart JK, Swartz ME, Crump JG, Kimmel CB. Early Hedgehog signaling from neural to oral epithelium organizes anterior craniofacial development. Development. 2006;133:1069–1077. doi: 10.1242/dev.02281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wada N, Javidan Y, Nelson S, Carney TJ, Kelsh RN, Schilling TF. Hedgehog signaling is required for cranial neural crest morphogenesis and chondrogenesis at the midline in the zebrafish skull. Development. 2005;132:3977–3988. doi: 10.1242/dev.01943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Cell autonomous requirement for PDGFRalpha in populations of cranial and cardiac neural crest cells. Development. 2003;130:507–518. doi: 10.1242/dev.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano P. The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roessler E, Belloni E, Gaudenz K, et al. Mutations in the human Sonic Hedgehog gene cause holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14:357–360. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada W, Nagao K, Horikoshi K, et al. Craniofacial malformation in R-spondin2 knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ. Mouse genetic models of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:63–77. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hruscha A, Krawitz P, Rechenberg A, et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing with low off-target effects in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:4982–4987. doi: 10.1242/dev.099085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sander JD, Cade L, Khayter C, et al. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) Eugene, Ore: University of Oregon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang R, Dodd A, Lai D, McNabb WC, Love DR. Validation of zebrafish (Danio rerio) reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR normalization. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2007;39:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisen JS, Smith JC. Controlling morpholino experiments: Don't stop making antisense. Development. 2008;135:1735–1743. doi: 10.1242/dev.001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker MB, Kimmel CB. A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae. Biotech Histochem. 2007;82:23–28. doi: 10.1080/10520290701333558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ekker SC, Larson JD. Morphant technology in model developmental systems. Genesis. 2001;30:89–93. doi: 10.1002/gene.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robu ME, Larson JD, Nasevicius A, et al. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker MB, Kimmel CB. A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae. Biotech Histochem. 2007;82:23–28. doi: 10.1080/10520290701333558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimmel CB, Miller CT, Moens CB. Specification and morphogenesis of the zebrafish larval head skeleton. Dev Biol. 2001;233:239–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gfrerer L, Dougherty M, Liao EC. Visualization of craniofacial development in the sox10: kaede transgenic zebrafish line using time-lapse confocal microscopy. J Vis Exp. 2013;79:e50525. doi: 10.3791/50525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunet FG, Roest Crollius H, Paris M, et al. Gene loss and evolutionary rates following whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1808–1816. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dougherty M, Kamel G, Shubinets V, Hickey G, Grimaldi M, Liao EC. Embryonic fate map of first pharyngeal arch structures in the sox10: kaede zebrafish transgenic model. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:1333–1337. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318260f20b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamel G, Hoyos T, Rochard L, et al. Requirement for frzb and fzd7a in cranial neural crest convergence and extension mechanisms during zebrafish palate and jaw morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2013;381:423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nair S, Li W, Cornell R, Schilling TF. Requirements for Endothelin type-A receptors and Endothelin-1 signaling in the facial ectoderm for the patterning of skeletogenic neural crest cells in zebrafish. Development. 2007;134:335–345. doi: 10.1242/dev.02704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tavares AL, Garcia EL, Kuhn K, Woods CM, Williams T, Clouthier DE. Ectodermal-derived Endothelin1 is required for patterning the distal and intermediate domains of the mouse mandibular arch. Dev Biol. 2012;371:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reid BS, Yang H, Melvin VS, Taketo MM, Williams T. Ectodermal Wnt/beta-catenin signaling shapes the mouse face. Dev Biol. 2011;349:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferretti E, Li B, Zewdu R, et al. A conserved Pbx-Wnt-p63-Irf6 regulatory module controls face morphogenesis by promoting epithelial apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2011;21:627–641. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall BK. Tissue interactions and the initiation of osteogenesis and chondrogenesis in the neural crest-derived mandibular skeleton of the embryonic mouse as seen in isolated murine tissues and in recombinations of murine and avian tissues. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1980;58:251–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwata J, Suzuki A, Pelikan RC, et al. Smad4-Irf6 genetic interaction and TGFβ-mediated IRF6 signaling cascade are crucial for palatal fusion in mice. Development. 2013;140:1220–1230. doi: 10.1242/dev.089615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video. Supplemental Digital Content 1 demonstrates cleft development in specc1lb morpholino knockdown morphant. Live time-lapse recording of developing ethmoid plate in a specc1lb morpholino knockdown Tg sox10:kaede zebrafish embryo (ventral view) at 60 hours post fertilization; sox10 provides lineage restriction of the kaede reporter protein to the neural crest. Failure of fusion between median ethmoid plate cells and lateral ethmoid plate cells can be observed. The video was recorded every 30 minutes starting 60 to 72 hours post fertilization, http://links.lww.com/PRS/B96.