Highlights

-

•

Diagnosis is often difficult and delayed because clinical symptoms are not specific.

-

•

The etiopathogenesis of jejuno–ileal diverticulosis is unclear.

-

•

Flatulent dyspepsia = epigastric pain abdominal discomfort, flatulence one or two hours after meals.

-

•

The extraluminal air develops an arrowhead-like shape surrounded by inflammatory tissue when the diverticulum is perforated.

-

•

In the presence of complications, surgical resection with reestablishment of the bowel continuity is the preferred treatment option.

Keywords: Acute abdomen, Small bowel diverticulum, Perforation, Surgery

Abstract

Introduction

Although diverticular disease of the duodenum and colon is frequent, the jejuno–ileal diverticulosis (JOD) is an uncommon entity. The perforation of the small bowel diverticula can be fatal due to the delay in diagnosis.

Presentation of case

We report the case of a 79-year-old man presenting with generalized abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Physical examination revealed a severe diffuse abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast showed thickening of the distal jejunal loop and thickening and infiltration of the mesenteric fat and the presence of free air in the mesentery suggesting a possible perforation adjacent to the diverticula. A midline laparotomy was performed. The jejunal diverticula were found along the mesenteric border. Forty centimeters of the jejunum were resected. Histopathology report confirmed the presence of multiple jejunual diverticula, and one of them was perforated. The patient tolerated the procedure and the postoperative period was uncomplicated.

Discussion

The prevalence of small intestinal diverticula ranges from 0.06% to 1.3%. The etiopathogenesis of JOD is unclear, although the current hypothesis focuses on abnormalities in the smooth muscle or myenteric plexus, on intestinal dyskinesis and on high intraluminal pressures. Diagnosis is often difficult and delayed because clinical symptoms are not specific and mainly imaging studies performs the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Because of the relative rarity of acquired jejuno–ileal diverticulosis, the perforation of small bowel diverticulitis poses technical dilemmas.

1. Introduction

Although diverticular disease of the duodenum and colon is frequent, the jejuno–ileal diverticulosis is a uncommon entity. Pathologically, they are pseudodiverticula of the pulsion type, resulting from increased intra-luminal pressure and weakening of the bowel wall. These diverticulosis are characterized by herniation of the mucosa and the submucosa through the muscular layer of the bowel wall [1,2].

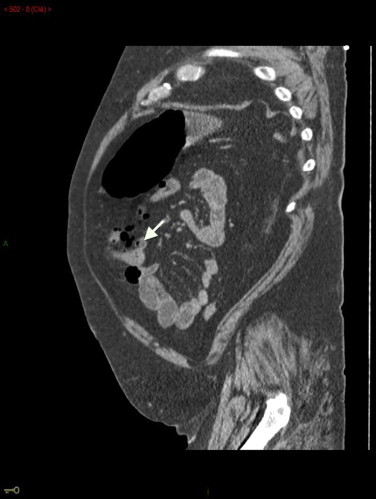

The perforation of the small bowel diverticula can be fatal due to the delay in diagnosis [3]. This case demonstrates the utility of Abdominal CT in diagnosing an extraluminal air bubble isolated in the mesentery that resulted from a perforated jejunal diverticulum. We wish to present this extremely rare case of perforated jejunal diverticulum in the mesentery, which is the first one that we have encountered in our practice, along with the accompanying diagnostic and therapeutic issues and a review of the literature.

2. Case presentation

We report the case of a 79-year-old man admitted to the emergency room for an acute onset of diffuse abdominal pain. The patient had a past medical history significant for hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and cholecystectomy. No known history of sigmoid diverticulitis. He was complaining of generalized abdominal pain, fatigue and altered bowel habits without fever. On physical examination our patient’s vital signs were a temperature 37.9 °C, heart rate 105, blood pressure 90/50 and respiratory rate 16 breaths/min. Abdominal examination revealed a generalized abdominal tenderness and signs of peritonitis. Laboratory investigations revealed an elevated white cell count (WCC 16,000 × 109/L). An urgent contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed thickening of the distal jejunal loop and thickening and infiltration of the mesenteric fat and the presence of free air in the mesentery suggesting a possible perforation (Fig. 1). The patient underwent a laparotomy which identified the presence of multiple diverticula of the jejunum with thickening and inflammation of a jejunal loop and its mesentery. After further dissection, a perforated diverticulum was identified along the mesenteric border.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT scan revealed: multiple diverticula of the small bowel (arrow), thickening of the jejunum due to diverticulitis, and elevation of density of the jejunal mesentery that contained extraluminal air (arrowhead). Findings are suggestive of perforated jejunal diverticulitis.

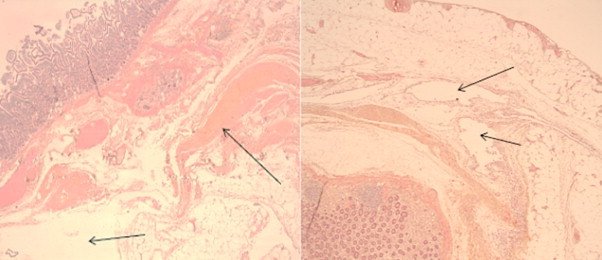

Forty centimeters of the jejunum were resected, carrying the perforated diverticulum and an end-to-end anastomosis was done. Histopathology report confirmed a multiple jejunal diverticula, one of them being perforated (Figs. 2 and 3). The patient tolerated the procedure and the postoperative period was uncomplicated.

Fig. 2.

Small jejuno–ileal diverticulitis.

Fig. 3.

Histology of the fragments (col. HES, ob. 2,5×). Jejuno–ileal diverticulosis involves only the mucosal and submucosal layers (false diverticula), and is characterized by herniation of mucosa and submucosa through the muscular layer of the bowel wall. Presence of emphysematous bulla in serous membrane.

3. Discussion

Jejuno–ileal diverticulosis was first described by Sommering in 1794. The prevalence of small intestinal diverticula ranges from 0.06% to 1.3% [4]. Most patients being in the sixth and seventh decade of life. Small bowel diverticula is twice as frequent in men than in women. The diverticula have a tendency to be smaller and fewer as one progresses distally in the small bowel. Diverticular disease is more common in the proximal jejunum (75%), followed by the distal jejunum (20%) and the ileum (5%) [5]. Co-existent diverticula can be present in the colon in 35–75%, of patients; in the duodenum in 15–42%, in the oesophagus in 2%, in the stomach in 2%, and in the urinary bladder in 12% of cases. There are two different kinds of small bowel diverticula: congenital diverticula (like the Meckel-diverticulum) and acquired diverticula. They must be distinguished from a Meckel’s diverticulum.

Jejuno–ileal diverticulosis involves only the mucosal and submucosal layers (false diverticula), and is characterized by herniation of mucosa and submucosa through the muscular layer of the bowel wall (Fig. 3). The herniation is placed through the weakest mesenteric site of the bowel wall. The areas of lesser resistance are at the points of vascular penetration induced by blood vessels [6]. With the exception of Meckel’s diverticulium, jejuno–ileal diverticulosis are acquired. The disease may often mask other disorders. They may be primary (acquired pulsion lesions or underlying visceral myopathy), or secondary to conditions like Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, and abdominal surgery. The etiopathogenesis of jejuno–ileal diverticulosis is unclear, although the current hypothesis focuses (predisposing factor) on abnormalities in the smooth muscle or myenteric plexus, on intestinal dyskinesis and on high intraluminal pressures. There are three types of microscopic abnormalities: 1/visceral neuropathy = axonal and neuronal degeneration. 2/visceral myopathy = fibrosis and degenerated smooth muscle cells. 3/progressive systemic sclerosis = fibrosis and decreased numbers of normal muscle cells.

Unlike those found in the colon, jejuno–ileal diverticula are mostly asymptomatic. No pathognomonic clinical symptoms indicating jejuno–ileal diverticulum has been reported. The clinical presentations are vague and diverse: chronic nonspecific symptoms like intermittent abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, dyspepsia and malnutrition and sometimes with acute presentation like gastrointestinal obstruction, diverticulitis (with or without associated hemorrhage), intra-abdominal abscess and perforation (covered or not). Diagnosis is often difficult and the diagnosis is performed mainly by imaging studies. A delayed diagnosis can be fatal, because perforation is associated with a high mortality in up to 40% of patients. 75% of jejuno–ileal diverticula are incidentally discovered during barium swallow, laparotomy or autopsy. The differential diagnosis includes neoplasms (with or without perforation), foreign body perforation, traumatic haematoma, medication-induced ulceration (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug), and Crohn’s disease.

The Jejunum is difficult to examine using the endoscopic methods; therefore, the radiographic diagnosis of these diverticula is the diagnostic tool of choice [7]. It is possible to detect jejuno–ileal diverticulosis by abdominal Ultrasound. However, there are limitations to this diagnostic tool like the presence of meteorism or adiposity. Abdominal CT is the diagnostic tool of choice even if it’s not possible to identify all small bowel diverticula. Abdominal CT can show a mass lesion containing extraluminal air bubbles, a dilated small bowel loop with hyperenhancing and thickened wall, the involvement of the surrounding tissue (e.g., fistula between the small bowel, colon, and bladder) and hyperdense appearance of the mesentery. This is the different point between perforated jejunal diverticulitis and the other small bowel perforations. Kubota et al. concluded “the extraluminal air develops an arrowhead-like shape surrounded by inflammatory tissue when the diverticulum is perforated”.

There is no consensus on therapeutic strategy and conservative management of the symptomatic jejunal diverticular disease. If the inflammation is mild, the medical management may be attempted (bowel rest and antibiotics). Surgery is the preferred treatment option. The resection is must be limited because: 1/even when the entire segment of small bowel containing diverticula is resected, the diverticula can recur. 2/reduce the risk of short bowel syndrome. The surgical techniques used: 1/suturing the perforation (with omental patch closure) 2/invaginating the diverticulum (with a suture) 3/segmental small bowel resection and primary anastomosis. The first two techniques should be abandoned due to a high mortality rate. In the presence of complications, surgical resection with reestablishment of the bowel continuity is the preferred treatment option.

In summary, jejuno–ileal diverticula is frequently overlooked as a possible source of abdominal infection in the elderly patient. Although jejunal diverticular disease is difficult to suspect, it should be considered as a cause of acute abdominal pain. Because of the relative rarity of acquired jejuno–ileal diverticulosis, even for the experienced surgeon, the perforation of small bowel diverticulitis pose technical dilemmas. The surgeon may encounter unusual findings like jejunal diverticulosis.

Conflict of interests

“Informed consent was obtained from the patient in writing for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review and can be obtained from the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request”.

Sources of funding

No source of funding for our research.

Consent

“Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request”.

Author contribution

Radwan Kassir: writing.

Sylviane Baccot: conceptualized and designed the paper.

Andy Petcu, Alexia Boueil, Tarek Debs: data collections.

Joelle Dubois: reviewed the paper.

Karine Abboud, Ugo Chevalier, Mathias Montveneur, Marie-Isabelle Cano, Romain Ferreira: reviewed the paper.

Olivier Tiffet: reviewed and revised the paper.

References

- 1.Zager J.S., Garbus J.E., Shaw J.P., Cohen M.G., Garber S.M. Jejunal diverticulosis: a rare entity with multiple presentations, a series of cases. Digest. Surg. 2000;17:643–645. doi: 10.1159/000051978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox R.D., Shatney C.H. Surgical implications of jejunal diverticula. South Med. J. 1988;81:1386–1391. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Haddawi F., Civil I.D. Acquired jejuno–ileal diverticular disease: a diagnostic and management challenge. ANZ J. Surg. 2015;200(373):584–589. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staszewicz W., CHristodoulou M., Proietti S., Dermartines N. Acute ulcerative jejunal diverticulitis: case report of an uncommon entity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;200(814):6265–6267. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C.Y., Chang W.H., Lin S.C., Chu C.H., Wang T.E., Shih S.C. Analysis of clinical manifestations of symptomatic acquired jejuno–ileal disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11(5557):e60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i35.5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woubet T.K., Josef F., Jens H. Complicated small-bowel diverticulosis: a case report and review of the literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2240–2242. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i15.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novose R., Valenciano J.S., De Souza Lima J.S., Nascimento E.F., Silva C.M., Martinez C.A. Jejunal diverticular perforation due to enterolith. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2015;20(115):445–451. doi: 10.1159/000330842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]