Abstract

Approximately 11% the Clostridium difficile genome is made up of mobile genetic elements which have a profound effect on the biology of the organism. This includes transfer of antibiotic resistance and other factors that allow the organism to survive challenging environments, modulation of toxin gene expression, transfer of the toxin genes themselves and the conversion of non-toxigenic strains to toxin producers. Mobile genetic elements have also been adapted by investigators to probe the biology of the organism and the various ways in which these have been used are reviewed.

Keywords: Conjugative transposon, PaLoc, Bacteriophage, Horizontal gene transfer, Tn5397, Tn916

1. Introduction

Approximately 11% of the Clostridium difficile genome is made up of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) [1] which provides the bacterium with a remarkable genetic plasticity. However the exact role of the mobile genome in the organism's biology, evolution and pathogenicity is only now beginning to be understood.

MGEs are highly heterogeneous and here we will define them in the loosest possible terms as any region of nucleic acid that can move from one part of a genome to another or between genomes. By this definition, MGEs range from the simple insertion sequences which contain only the genetic information required for movement from one part of the genome to another, to bacteriophage, large conjugative transposons and mega plasmids which are complex genomes in themselves. In this review we will provide examples of some of these genetic elements and discuss the mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer and the consequent biological effects on the host cell.

2. Plasmids

Plasmids are extra chromosomal genetic elements which range in size from very small, around 1.5 kb to mega plasmids which can reach the size of bacterial genomes e.g. [2]. In C. difficile, plasmids have been identified in several different strains [1,3–5]. To our knowledge no phenotype has been found to be conferred on C. difficile by a naturally occurring plasmid. However, naturally occurring C. difficile plasmids have been used to generate vectors for the genetic manipulation of the organism [6,7].

The plasmids used as the basis for C. difficile genetic manipulation are small and cryptic and contain only the genetic information required for their replication and maintenance. The subsequent addition of Escherichia coli origins of replication and origins of transfer allowed the construction of shuttle vectors that can replicate in both C. difficile and E. coli and can be mobilised from E. coli to C. difficile [6,7]. Vectors based on these cryptic C. difficile plasmids have been extensively modified to provide a range of research tools for the bacterium [8,9].

3. IS sequences

These are simple MGEs, containing just the genetic information required to translocate from one part of the genome to another. However IS elements in C. difficile have not been investigated to date and they will not be discussed further here. However IStrons which are a hybrid element consisting of an IS element and a group I intron are discussed below.

4. The mobile introns

Introns were first discovered in 1977 when it was found that eukaryotic genes were split, i.e. that the coding region was interrupted by non-coding sequences (introns) that were spliced out of the RNA transcripts before being translated [10,11]. At the time this was a surprising finding that represented a paradigm shift in our understanding of biology. Initially it was thought that bacteria and their viruses did not contain introns however this notion was shown to be incorrect with the finding of an intron in a phage genome [12]. Subsequently introns have been found in many different bacteria, nearly always found in association with mobile DNA, although they are rare in prokaryotes compared to eukaryotes. Bacterial introns are classified into either group I or group II according to their conserved secondary structure [13].

4.1. Group II introns

The first intron found in C. difficile was a group II intron and it was contained within orf14 of the conjugative transposon, Tn5397 [14]. Group II introns often contain an ORF encoding a multifunctional protein made up of maturase, endonuclease and reverse transcriptase domains. This multi-functional protein becomes part of a riboprotein complex in conjunction with the intron-encoded RNA. This riboprotein complex is required for effective splicing and the riboprotein can catalyse intron transposition [13]. Work in our laboratory has shown that the C. difficile intron is capable of splicing and that the intron-encoded protein is required for this process [15]. Transposition of this element has not been demonstrated, but group II introns have been found in other C. difficile elements suggesting that they are capable of transposition [16].

The contribution of the mobile group II introns to C. difficile biology has not been determined but, as one has been shown to splice perfectly from its host gene [15] and has a small size, their biological costs are likely to be low. Group II introns may have a role in regulation as differential splicing can allow alternative proteins to be produced. This has not been demonstrated in C. difficile but in Clostridium tetani, a group II intron has been characterised and shown to undergo alternative splicing to produce different isoforms of surface layer proteins [17]. Group II introns have been used in biotechnological approaches forming the basis of the TargeTron which has been used for making targeted gene knock-outs [18]. TargeTrons adapted for the clostridia have been termed ‘clostrons’ [8].

4.2. IStrons

IStrons are hybrid genetic elements combining a group I intron and an insertion sequence [19]. The whole element is capable of both splicing out of primary transcripts and transposing to new genomic sites. These elements are relatively wide-spread in C. difficile. Analysis of the splicing reaction in IStrons has shown that they can have alternative splice sites leading to the production of variant proteins [19]. As IStrons have been found inserted into the C. difficile toxin A gene, alternative splicing could produce alternative toxins [19], although IStron mediated toxin variation has not yet been demonstrated.

5. Conjugative and mobilisable transposons

Conjugative transposons (CTns) also called Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICE), are genetic elements that are capable of transferring themselves from a donor cell to a recipient using a conjugation-like mechanism. Unlike plasmids these elements do not normally contain an origin of replication so in order to survive they must be integrated into a replicon. Mobilisable transposons (MTns) can also be transferred by a conjugation-like mechanism but these elements lack the genes required for conjugation and use those of CTns or conjugative plasmids that are present in the same cell. For a detailed discussion of the properties of these types of elements, the reader is referred to the following recent reviews [20–23]. Here we will discuss what is known about the CTns and MTns from C. difficile.

Several DNA sequencing projects have shown that C. difficile contains a plethora of putative CTns and MTns and some of these are proven to be active and capable of conjugative transfer [1,16,24,25]. The typical genetic organisation of these elements is that they contain regions required for integration and excision, conjugation (in the case of CTns, this is absent in MTns), regulation and an accessory region. The latter usually contains genes which are thought to allow the bacterium to survive in particularly challenging environments, such as antibiotic resistance genes and ABC transporters [16]. Some CTns have been shown to encode sigma factors; whether these are required for regulation of the CTn itself or have a more global role in the host biology is not known.

Surprisingly, despite the large number of CTns and MTns detected in different strains of C. difficile, very few have been studied in detail. Although bioinformatics analysis has led to predictions of how these elements might affect the biology of C. difficile, there is little experimental evidence. The following section will discuss what is known about how these elements affect the biology of their host.

5.1. Tn5397 and Tn916

Tn5397 is the best understood of the C. difficile CTns. It was originally discovered in strain 630 where it conferred tetracycline resistance [14,26,27]. It is capable of transferring between C. difficile strains and to and from Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecalis and the element has also been found in Streptococcus spp. [27–29]. The element is 21 kb in size and is very closely related to Tn916, the paradigm for this family of MGEs [30]. The ends of the elements are very different and Tn5397 encodes a large serine recombinase, TndX, responsible for integration and excision [31]. TndX directs the element into two highly preferred insertion sites in C. difficile R20291 [32]. However in B. subtilis there are no obvious preferred insertion sites apart from a central GA dinucleotide which is always present in the target site.

Both Tn916 and Tn5397 confer tetracycline resistance on C. difficile but in contrast to Tn916, which inserts into multiple regions of the genome (see below), Tn5397 inserts into DNA predicted to encode a domain initially termed Fic (filamentation processes induced by cAMP). This was characterised in E. coli where mutation of the fic gene resulted in filamentous growth [33]. Latter work showed that Fic domains are ubiquitous in all domains of life and they can be present in a myriad of different proteins, reviewed in [34]. Proteins containing Fic domains are involved in post-translational modification of their targets via UMPylation, AMPylation, phosphorylation, or phosphocholination [34]. In order to determine if the sequence of the C. difficile Fic encoding domain itself is responsible for the remarkable targeting of this region by Tn5397 we cloned it into B. subtilis and showed that Tn5397 always entered the genome in the cloned sequence encoding the Fic domain, demonstrating that if this region is present it is used by Tn5397 [32]. Band shift assays showed that this was most likely a result of TndX showing preferential binding to the sequence in the Fic encoding domain [32]. It is intriguing that TndX has evolved to target Fic encoding domains; perhaps because these are ubiquitous in all forms of life they provide a suitable target for a promiscuous CTn.

Tn916 has also been found in C. difficile and transferred into this organism from B. subtilis [35]. In contrast to Tn5397, Tn916 contains genes encoding a tyrosine recombinase and an excisionase which are responsible for integration and excision of the element. This difference results in Tn916 having the ability to insert into multiple sites in the C. difficile genome although it does have a preferred consensus site which is present in the C. difficile genome 105 times [35]. This consensus is present more times in intergenic regions than within ORFs [35].

Tn916 has also been used as a tool for the investigation of C. difficile biology, both for mutagenesis [35] and for gene cloning in the organism [7,36,37]. As a tool for mutagenesis, the site preferences noted above for the element is a disadvantage. Another system for C. difficile transposon mutagenesis has been developed based on a Mariner transposon and it is likely that this system will be the mutagenesis tool of choice as it does not appear to suffer from the site specificity of Tn916 [9]. However, since the first report of a C. difficile Mariner system in 2010, no large scale mutagenesis studies have been reported suggesting that Tn916 may have to be revisited as a tool for mutagenesis.

Tn916 was the first genetic element used for successful cloning in C. difficile and it made use of the fact that cargo DNA can be added to the region of Tn916 upstream of the tet(M) gene without affecting its conjugative ability. A vector that contained regions of homology to Tn916 was designed and this was transformed into B. subtilis and the recombinant transposon could be transferred by conjugation to C. difficile [36]. Cloning into Tn916 has been used to investigate the role of the virR [7] cwp66 [37] and the skin element (see below) [38].

5.2. Tn4453a and Tn4453b

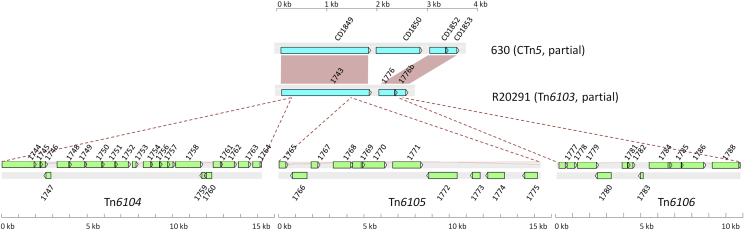

Tn4453a and Tn4453b were initially found in C. difficile strain W1 where they conferred resistance to chloramphenicol [39]. These two elements only differ from each other by a few base pairs and are very closely related to the Clostridium perfringens MTn, Tn4451 [40]. When Tn4451 was cloned in E. coli it could be mobilised by plasmid RP4 to C. perfringens [41]. Although the C. difficile MTns could not be transferred in the laboratory, the fact that they are very closely related to a proven MTn suggests that they are likely to be capable of mobilisation. Genetic elements related to Tn4453 and Tn4451 have been found contained within the large C. difficile CTn, Tn6103 [16] Fig. 1. One of these elements, Tn6104, could excise from Tn6103. Unlike Tn4453 which contains the chloramphenicol resistance gene catD, Tn6104 has genes predicted to encode a transcriptional regulator, a two component regulatory system, an ABC transporter, three sigma factors and a putative toxin-antitoxin system [16]. The role of these genes in C. difficile biology remains to be determined.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of part of CTn5 from C. difficile 630 to the part of Tn6103 that contains the three putative MTns. The red boxes represent homologous genes between CTn5 and Tn6103. The points of insertion of the three putative MTns are represented by the dotted lines. (Figure reproduced from; Brouwer MSM, Warburton PJ, Roberts AP, Mullany P, Allan E. (2011) Genetic organisation, mobility and predicted functions of genes on integrated, mobile genetic elements in sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS ONE 6(8): e23014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023014).

5.3. Tn5398

Tn5398 was originally discovered because it was responsible for transferable macrolide, lincomycin, streptogramin B (MLS) resistance, encoded by the erm(B) gene [42,43]. The element was capable of transfer between C. difficile and B. subtilis [42] and between C. difficile and Staphylococcus aureus [43]. Comparison of the sequences in transconjugant and recipients, allowed the ends of the element to be determined showing that it was 9.6 kb in length [44]. Tn5398 is a rather unusual element as it does not contain any obvious recombinases and no circular forms have been found. However the element does contain putative origins of transfer (oriT) sites. There are at least two ways, which are not mutually exclusive, in which Tn5398 could transfer. One of the CTns present in the donor strain could provide integration/excision functions to generate a circular intermediate molecule which is then nicked at the oriT site and transferred to a recipient using the conjugation functions of a CTn; integration in the recipient could either be by homologous recombination or by using a site-specific recombinase in the recipient. The other possibility is that the element is not excised but that a portion of the genome is transferred to the recipient and integrates into the recipient chromosome by homologous recombination. This process is analogous to high frequency recombination (hfr) seen when the E. coli F-factor is integrated into the chromosome and mobilises transfer of the whole chromosome to a suitable recipient. In this case, one of the integrated CTns could be mediating the transfer; this would require that the mobilising CTn does not excise. We have proposed that this is the mechanism responsible for transfer of the PaLoc, see below. It should be noted that the term hfr for these types of transfer events is confusing as they are not high frequency recombination events; we propose that the term chromosomal transfer and recombination (CTaR) is used instead.

A genetic element that also encodes resistance to MLS antibiotics mediated by an ermB gene has been found in C. difficile. This element, Tn6194, has a conjugation region that is closely related to that of Tn916 but contains an accessory region that is related to Tn5398 [45]. This modular composition is commonly observed amongst the MGEs in C. difficile. A Tn6194-like element has been shown to be capable of transfer between C. difficile strains and to E. faecalis [45].

6. The skinCd element

The sigK intervening sequence (skin) element was originally identified as a prophage-like sequence integrated into the B. subtilis sigK gene [46]. When B. subtilis sporulates, the element excises only in the mother cell, resulting in an intact sigK gene and production of the sigma factor K which is required for the sporulation cascade. C. difficile also contains a skin element, skinCd integrated into the sigK gene [38]. In common with B. subtilis, excision of this element in the mother cell is required for sporulation [38]. In contrast to B. subtilis, however, C. difficile strains that do not contain the skin element sporulate very poorly. SkinCd is much smaller than the B. subtilis skin element at 14 kb and appears to be degenerate, only retaining its site-specific recombinase (required for excision in the mother cell). A plausible scenario for the evolution of skinCd is that a prophage entered the sigK gene in an ancestral C. difficile strain and became adapted to sense the cellular stress that is a prelude for sporulation (and the phage lytic cycle) so that it excised and entered the lytic cycle. It must also have had the ability to avoid excision from the genome destined for the spore so that the prophage genome was maintained. Further evolutionary events may have resulted in the element losing the ability to kill the host and further integration into the host cell's physiology.

The exact role of skinCd has not been determined but it may be involved in the correct timing of SigK production [47]. However the regulatory signal that induces skinCd to excise has not been determined.

7. Bacteriophages

C. difficile has been shown to contain a number of different bacteriophages; for a recent review see Hargreaves and Clokie [48]. Three of these phages, ϕCD119, ϕCD38-2 and ϕCD27 are able to up- and down-regulate production of the toxins [49–51]. In the case of ϕCD119, this occurs by direct binding of a regulatory protein to the region upstream of tcdR within the PaLoc which encodes a positive regulator of toxin production [49].

The phage ΦC2 has been shown to mediate the transduction of an MLS resistance gene contained within an MTn Tn6215 [52]. This is the first example of transduction in C. difficile demonstrating that phage have a role in mediating the spread of antibiotic resistance and potentially in the spread of other genes.

Phage particles have been found in the stools of patients infected with C. difficile demonstrating that lytic phage is produced during infection. Identical phages were found within the genome of the infecting strain, indicating that the phages were induced within the patients [53]. These workers also showed that lysogens of these phages could be induced to produce viral particles by treatment with sub-inhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and mitomycin C suggesting that administration of these antibiotics to C. difficile-infected patients will promote phage mobility.

Phages also have the potential to be used as therapy for C. difficile associated disease. They are considered particularly attractive in this regard as they will specifically kill C. difficile without collateral damage to the microbiota. Phage ϕCD27 has been evaluated in a gut ecosystem model where it showed promise in treatment of a model infection compared to an untreated control [54]. However, for phages to be safely used, we need to understand more about their biology to avoid unwanted side effects like the transduction of antibiotic resistance genes and the up-regulation of toxin genes. Another problem encountered with the development of phage as therapeutic agents for C. difficile infection, is that all of those investigated to date form lysogens which would prevent efficient killing of all the infecting bacteria.

8. Transfer of the PaLoc

The PaLoc contains the genes encoding toxins A and B, the major virulence factors of the organism [55]. In addition to these genes, it contains a gene encoding a positive regulator of toxin gene expression, tcdD [56], a homologue of a phage holin, tcdE, and tcdC (see below). There is some controversy in the role of TcdE in toxin release and its exact role requires further experiments [57,58]. TcdC was initially proposed to be a negative regulator of toxin production but recent genetic evidence does not support this idea [59,60]. The PaLoc has some of the properties of a MGE as it occupies the same genomic location in all toxigenic strains and in non-toxigenic strains; it is replaced with 115 bp of non-coding sequence [55]. The phage-like holin gene and regulatory interaction with various phage also implies a relationship with MGEs [49,50]. However the element does not contain an obvious oriT, nor does it contain any predicted recombinase genes. Despite these observations, we have shown that the PaLoc is capable of transfer from toxigenic to non-toxigenic strains [61].

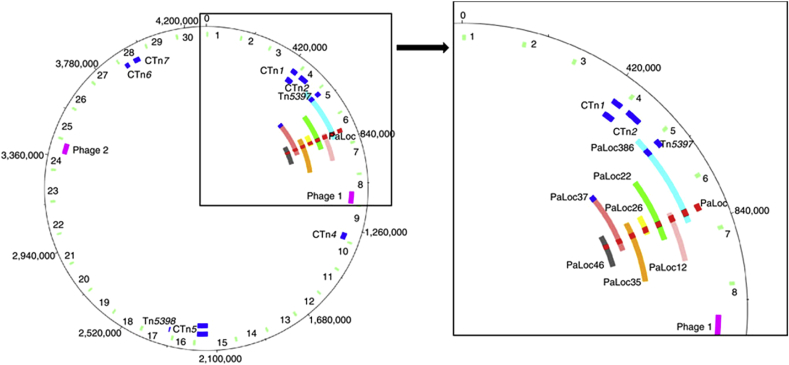

PaLoc transfer was initially discovered when selecting for a genetically marked copy of CTn2 from C. difficile 630 to CD37. When investigating the transconjugants for co-transfer of non-selected genetic elements, it was found that one transconjugant also contained the PaLoc. Further transfer experiments with a donor bearing a PaLoc with an erythromycin resistance gene within toxB reproducibly yielded transconjugants and investigation of these showed that the PaLoc was transferred on variable sized genomic fragments ranging from 66 kbp to 272 kbp. This study also showed that the PaLoc was frequently co-transferred with CTns (Fig. 2) [61]. The transfer frequency of PaLoc and CTn was low, approximately 1 transconjugant per 108 recipients however a non-selected CTn was almost always observed in transconjugants containing the PaLoc indicating that PaLoc and CTn transfer are linked. The exact mechanism behind this linkage is still under investigation however a hypothesis that explains these observations is that that one or more of the CTns provides an integrated origin of transfer for the transfer of large genome fragments containing the PaLoc. We propose that if a CTn does not excise, it may promote the transfer of large genomic fragments by CTaR.

Fig. 2.

Demonstration of transfer of the PaLoc. The left panel represents the C. difficile 630 genome. The outer circle represents the C. difficile genome the green bands on the second circle represent 10 kb fragments around the 630 genome that contain snips and indels that differentiate the 630 donor genome from the CD37 recipient genome; the dark blue fragments on the third circle represents the location of CTns the red fragment on the third circle represent the location of the PaLoc, the purple fragments on the third circle represent the location of prophage. The fourth to the tenth circle represent CD37 transconjugants containing the PaLoc, transferred fragments are shown by coloured lines, transferred CTns and PaLocs are shown. The right hand panel shows the region containing the PaLoc in more detail. (for more details see reference [47]). Figure reproduced from; Brouwer MS, Roberts AP, Hussain H, Williams RJ, Allan E, Mullany P. (2013). Horizontal gene transfer converts non-toxigenic Clostridium difficile strains into toxin producers. Nature Communications. 4, 2601.

Importantly, it was shown that the newly acquired toxin genes were expressed in the previously non-toxigenic strain, CD37, showing that non-toxigenic strains have the potential to be converted to toxin producers [61]. This is an important observation as non-toxigenic strains have been proposed as therapeutic agents for C. difficile disease [62], and there is an urgent need therefore to understand the factors promoting transfer of the PaLoc.

9. Conclusions

C. difficile contains a large number of MGEs and as we have discussed above, these have a wide-ranging effect on the biology of the bacterium. The major virulence factors of the organism, toxins A and B, are contained on a genetic island, the PaLoc, which is itself transferable on large genomic fragments, most likely mediated by the integrated CTns. In addition, bacteriophages can modulate expression of the toxin genes within the PaLoc. Thus, MGEs have a profound influence on the organism's pathogenicity. Further examples include the ability of Tn5397 to insertionally target C. difficile genes containing Fic domains, which may have a role in virulence. MGEs also affect the biology of the organism in other ways: by spreading antibiotic resistance and other phenotypes enabling adaptation to stressful environments. The fact that some MGEs encode predicted sigma factors and other regulators indicates that these elements have the potential to modulate the regulatory pathways of C. difficile with, as yet unknown, but potentially profound consequences on the biology of the organism. Furthermore, the large number of MGEs in C. difficile and the genetic flexibility they afford undoubtedly contributes to the evolutionary success of this organism.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for to the MRC (G0601176), European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 223585 for funding part of the work undertaken in our laboratories.

Contributor Information

Peter Mullany, Email: p.mullany@ucl.ac.uk.

Elaine Allan, Email: e.allan@ucl.ac.uk.

Adam P. Roberts, Email: adam.roberts@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Sebaihia M., Wren B.W., Mullany P., Fairweather N.F., Minton N., Stabler R. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tett A., Spiers A.J., Crossman L.C., Ager D., Ciric L., Dow J.M. Sequence-based analysis of pQBR103; a representative of a unique, transfer-proficient mega plasmid resident in the microbial community of sugar beet. ISME J. 2007;1:331–340. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clabots C., Lee S., Gerding D., Mulligan M., Kwok R., Schaberg D. Clostridium difficile plasmid isolation as an epidemiologic tool. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7:312–315. doi: 10.1007/BF01963112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clabots C.R., Peterson L.R., Gerding D.N. Characterization of a nosocomial Clostridium difficile outbreak by using plasmid profile typing and clindamycin susceptibility testing. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:731–736. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muldrow L.L., Archibold E.R., Nunez-Montiel O.L., Sheehy R.J. Survey of the extrachromosomal gene pool of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:637–640. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.637-640.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purdy D., O'Keeffe T.A., Elmore M., Herbert M., McLeod A., Bokori-Brown M. Conjugative transfer of clostridial shuttle vectors from Escherichia coli to Clostridium difficile through circumvention of the restriction barrier. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:439–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minton N., Carter G., Herbert M., O'keeffe T., Purdy D., Elmore M. The development of Clostridium difficile genetic systems. Anaerobe. 2004;10:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heap J.T., Cartman S.T., Kuehne S.A., Cooksley C., Minton N.P. ClosTron-targeted mutagenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;646:165–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-365-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartman S.T., Minton N.P. A mariner-based transposon system for in vivo random mutagenesis of Clostridium difficile. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;6:1103–1109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02525-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow L.T., Gelinas R.E., Broker T.R., Roberts R.J. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5' ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell. 1977;12:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinniburgh A., Mertz J., Ross J. The precursor of mouse β-globin messenger RNA contains two intervening RNA sequences. Cell. 1978;14:681–693. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu F.K., Maley G.F., Maley F., Belfort M. Intervening sequence in the thymidylate synthase gene of bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3049–3053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belfort M., Perlman P.S. Mechanisms of intron mobility. J Biological Chem. 1995;270:30237–30240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullany P., Pallen M., Wilks M., Stephen J.R., Tabaqchali S. A group II intron in a conjugative transposon from the gram-positive bacterium, Clostridium difficile. Gene. 1996;174:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts A.P., Braun V., von Eichel-Streiber C., Mullany P. Demonstration that the group II intron from the clostridial conjugative transposon Tn5397 undergoes splicing in vivo. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1296–1299. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1296-1299.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwer M.S., Warburton P.J., Roberts A.P., Mullany P., Allan E. Genetic organisation, mobility and predicted functions of genes on integrated, mobile genetic elements in sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeil B.A., Simon D.M., Zimmerly S. Alternative splicing of a group II intron in a surface layer protein gene in Clostridium tetani. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1959–1969. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karberg M., Guo H., Zhong J., Coon C., Perutka J., Lamberwitz A.M. Group II introns as controllable gene targeting vectors for genetic manipulation of bacteria. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1162–1167. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V., Mehlig M., Moos M., Rupnik M., Kalt B., Mahony D.E. A chimeric ribozyme in Clostridium difficile combines features of group I introns and insertion elements. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1447–1459. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wozniak R.A., Waldor M.K. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:552–563. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts A.P., Mullany P. Tn916-like genetic elements: a diverse group of modular mobile elements conferring antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:856–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts A.P., Mullany P. A modular master on the move: the Tn916 family of mobile genetic elements. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters J.L., Salyers A.A. Regulation of CTnDOT conjugative transfer is a complex and highly coordinated series of events. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00569-13. e00569–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He M., Sebaihia M., Lawley T.D., Stabler R.A., Dawson L.F., Martin Evolutionary dynamics of Clostridium difficile over short and long time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7527–7532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914322107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brouwer M.S., Roberts A.P., Mullany P., Allan E. In silico analysis of sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile reveals a related set of conjugative transposons carrying a variety of accessory genes. Mob Genet Elem. 2012;2:8–12. doi: 10.4161/mge.19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hächler H., Kayser F.H., Berger-Bächi B. Homology of a transferable tetracycline resistance determinant of Clostridium difficile with Streptococcus (Enterococcus) faecalis transposon Tn916. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1987;7:1033–1038. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullany P., Wilks M., Lamb I., Clayton C., Wren B., Tabaqchali S. Genetic analysis of a tetracycline resistance element from Clostridium difficile and its conjugal transfer to and from Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1343–1349. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-7-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jasni A.S., Mullany P., Hussain H., Roberts A.P. Demonstration of conjugative transposon (Tn5397)-mediated horizontal gene transfer between Clostridium difficile and Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4924–4926. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00496-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenciani A., Bacciaglia A., Vecchi M., Vitali L.A., Varaldo P.E., Giovanetti E. Genetic elements carrying erm(B) in Streptococcus pyogenes and association with tet(M) tetracycline resistance gene. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1209–1216. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01484-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts A.P., Johanesen P.A., Lyras D., Mullany P., Rood J.I. Comparison of Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile, Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis and the CW459tet(M) element from Clostridium perfringens shows that they have similar conjugation regions but different insertion and excision modules. Microbiology. 2001;147:1243–1251. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H., Mullany P. The large resolvase TndX is required and sufficient for integration and excision of derivatives of the novel conjugative transposon Tn5397. J Bacteriol. 2000;23:6577–6583. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6577-6583.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H., Smith M.C., Mullany P. The conjugative transposon Tn5397 has a strong preference for integration into its Clostridium difficile target site. J Bacteriol. 2006;13:4871–4878. doi: 10.1128/JB.00210-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utsumi R., Nakamoto Y., Kawamukai M., Himeno M., Komano T. Involvement of cyclic AMP and its receptor protein in filamentation of an Escherichia coli fic mutant. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:807–812. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.807-812.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Pino A., Zenkin N., Loris R. The many faces of Fic: structural and functional aspects of Fic enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullany P., Williams R., Langridge G.C., Turner D.J., Whalan R., Clayton C. Behaviour and target site selection of conjugative transposon Tn916 in two different strains of toxigenic Clostridium difficile. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;7:2147–2153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06193-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullany P., Wilks M., Puckey L., Tabaqchali S. Gene cloning in Clostridium difficile using Tn916 as a shuttle conjugative transposon. Plasmid. 1994;3:320–323. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts A.P., Hennequin C., Elmore M., Collignon A., Karjalainen T., Minton N.P. Development of an integrative vector for the expression of antisense RNA in Clostridium difficile. J Microbiol Methods. 2003;55:617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haraldsen J.D., Sonenshein A.L. Efficient sporulation in Clostridium difficile requires disruption of the sigmaK gene. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:811–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wren B.W., Mullany P., Clayton C., Tabaqchali S. Molecular cloning and genetic analysis of a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase determinant from Clostridium difficile. Not Found In Database. 1988;32:1213–1217. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyras D., Storie C., Huggins A.S., Crellin P.K., Bannam T.L., Rood J.I. Chloramphenicol resistance in Clostridium difficile is encoded on Tn4453 transposons that are closely related to Tn4451 from Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1563–1567. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams V., Lyras D., Farrow K.A., Rood J.I. The clostridial mobilisable transposons. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:2033–2043. doi: 10.1007/s000180200003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullany P., Wilks M., Tabaqchali S. Transfer of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance in Clostridium difficile is linked to a gene homologous with toxin A and is mediated by a conjugative transposon, Tn5398. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;2:305–315. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hächler H., Berger-Bächi B., Kayser F.H. Genetic characterization of a Clostridium difficile erythromycin-clindamycin resistance determinant that is transferable to Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1987;7:1039–1045. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farrow K.A., Lyras D., Rood J.I. Genomic analysis of the erythromycin resistance element Tn5398 from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology. 2001;147:2717–2728. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-10-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasels F., Monot M., Spigaglia P., Barbanti F., Ma L., Bouchier C. Inter- and intraspecies transfer of a Clostridium difficile conjugative transposon conferring resistance to MLSB. Microb Drug Resist. 2014;20:555–560. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krogh S., O'Reilly M., Nolan N., Devine K.M. The phage-like element PBSX and part of the skin element, which are resident at different locations on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome, are highly homologous. Microbiology. 1996;142(Pt 8):2031–2040. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pereira F.C., Saujet L., Tomé A.R., Serrano M., Monot M., Couture-Tosi E. The spore differentiation pathway in the enteric pathogen Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hargreaves K.R., Clokie M.R. Clostridium difficile phages: still difficult? Front Microbiol. 2014;5:184. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Govind R., Vediyappan G., Rolfe R.D., Dupuy B., Fralick J.A. Bacteriophage-mediated toxin gene regulation in Clostridium difficile. J Virol. 2009;83:12037–12045. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sekulovic O., Meessen-Pinard M., Fortier L.C. Prophage-stimulated toxin production in Clostridium difficile NAP1/027 lysogens. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2726–2734. doi: 10.1128/JB.00787-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams R., Meader E., Mayer M., Narbad A., Roberts A.P., Mullany P. Determination of the attP and attB sites of phage CD27 from Clostridium difficile NCTC 12727. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1439–1443. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.058651-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goh S., Hussain H., Chang B.J., Emmett W., Riley T.V., Mullany P. Phage ϕC2 mediates transduction of Tn6215, encoding erythromycin resistance, between Clostridium difficile strains. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00840-13. e00840–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meessen-Pinard M., Sekulovic O., Fortier L.C. Evidence of in vivo prophage induction during Clostridium difficile infection. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012 Nov;78(21):7662–7670. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02275-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meader E., Mayer M.J., Steverding D., Carding S.R., Narbad A. Evaluation of bacteriophage therapy to control Clostridium difficile and toxin production in an in vitro human colon model system. Anaerobe. 2013;22:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braun V., Hundsberger T., Leukel P., Sauerborn M., von Eichel-Streiber C. Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene. 1996;181:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mani N., Dupuy B. Regulation of toxin synthesis in Clostridium difficile by an alternative RNA polymerase sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:5844–5849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101126598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olling A., Seehase S., Minton N.P., Tatge H., Schröter S., Kohlscheen S. Release of TcdA and TcdB from Clostridium difficile cdi 630 is not affected by functional inactivation of the tcdE gene. Microb Pathog. 2012;52:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Govind R., Dupuy B. Secretion of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B requires the holin-like protein TcdE. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002727. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cartman S.T., Kelly M.L., Heeg D., Heap J.T., Minton N.P. Precise manipulation of the Clostridium difficile chromosome reveals a lack of association between the tcdC genotype and toxin production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4683–4690. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00249-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bakker D., Smits W.K., Kuijper E.J., Corver J. TcdC does not significantly repress toxin expression in Clostridium difficile 630ΔErm. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brouwer M.S., Roberts A.P., Hussain H., Williams R.J., Allan E., Mullany P. Horizontal gene transfer converts non-toxigenic Clostridium difficile strains into toxin producers. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2601. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villano S.A., Seiberling M., Tatarowicz W., Monnot-Chase E., Gerding D.N. Evaluation of an oral suspension of VP20621, spores of nontoxigenic Clostridium difficile strain M3, in healthy subjects. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2012;10:5224–5229. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00913-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]