Abstract

Priapism is an erectile disorder involving uncontrolled, prolonged penile erection without sexual purpose, which can lead to erectile dysfunction. Ischemic priapism, the most common of the variants, occurs with high prevalence in patients with sickle cell disease. Despite the potentially devastating complications of this condition, management of recurrent priapism episodes historically has commonly involved reactive treatments rather than preventative strategies. Recently, increasing elucidation of the complex molecular mechanisms underlying this disorder, principally involving dysregulation of nitric oxide signaling, has allowed for greater insights and exploration into potential therapeutic targets. In this review, we discuss the multiple molecular regulatory pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of priapism. We also identify the roles and mechanisms of molecular effectors in providing the basis for potential future therapies.

Keywords: Adenosine, Nitric Oxide, Opiorphins, Rho Kinase, Recurrent Ischemic Priapism Treatment, Testosterone

Introduction

Priapism is a disorder of penile erectile function involving persistent erection continuing beyond, or unrelated to, sexual interest or desire [1]. Overall estimates of incidence rates of this condition range from 0.34 to 1.5 per 100,000 [2, 3]. However, significantly higher prevalence rates have been noted in certain populations such as patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), in whom prevalence rates of priapism as high as 30–40% have been reported [4–6]. This population is at an elevated risk of recurrent ischemic priapism (RIP), also termed stuttering priapism, a variant of the common and often painful ischemic (low flow or veno-occlusive) priapism [1]. RIP, as its name implies, involves repeated ischemic episodes, which are typically transient and self-limiting, occurring during sleep and lasting less than 3 hours in duration [1, 7]. Although transient, this variant may be a harbinger of longer, major episodes as nearly 30% of RIP cases have been reported to progress to a major episode of ischemic priapism [5].

Ischemic priapism, particularly if untreated, can result in devastating time-dependent complications related to erectile tissue ischemia and damage with subsequent sequelae of cavernosal fibrosis followed by erectile dysfunction (ED) [8, 9]. Significant psychological and social effects are also associated with this condition [10]. However, these complications are not limited to ischemic priapism, as ED has also been described as a complication of RIP, with reported occurrence rates between 29–36% [5, 6]. Given these severe complications, treatment and, more importantly, prevention of recurrent episodes are paramount objectives. Current management approaches are deficient in regards to safe and effective prophylaxis. Through recent scientific discoveries, an increased understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanism of ischemic priapism has led to the identification of new pathways and potential directions for future treatments. Here, we review the molecular pathways involved in ischemic priapism as well as current therapeutic options and prospective targets for future therapies for RIP.

Normal Erectile Physiology

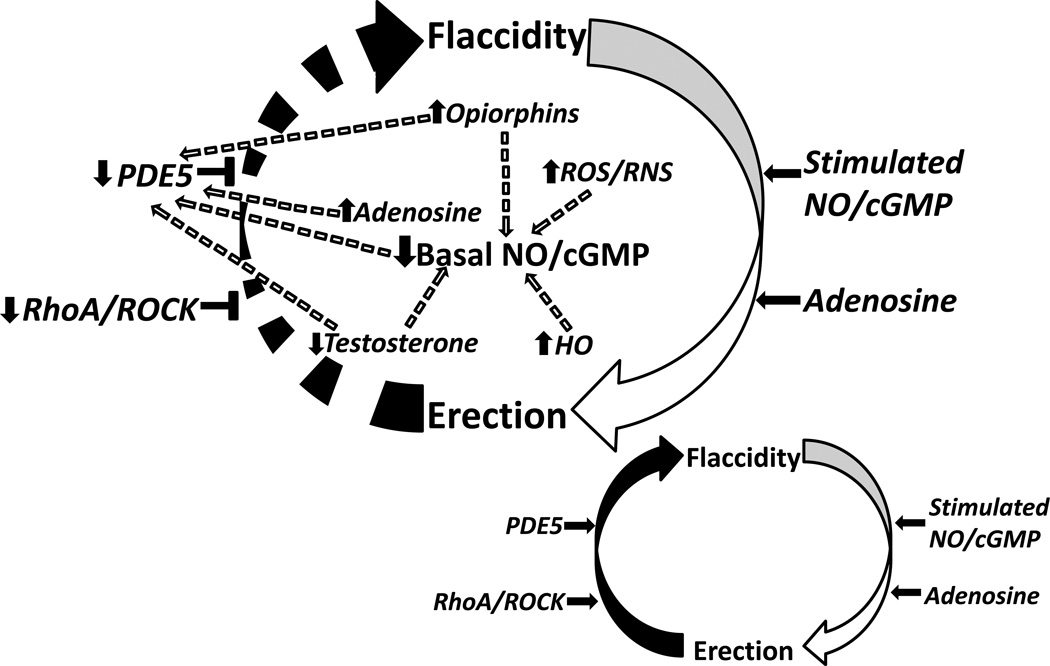

Recent discoveries have identified the critical role of the nitric oxide (NO)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway in normal erectile physiology (Figure 1 inset). Stimulation of the normal erectile response typically involves both vascular and neurogenic pathways regulated by the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzyme, the principal mediator of NO synthesis. The constitutive forms of this enzyme, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) (found in nerve terminals) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (found in vascular and sinusoidal endothelium), are responsible for both the initiation and maintenance phases of penile erection [11]. Upon phosphorylation, these principal NOS isoforms are activated and function to generate NO from the substrate, L-arginine [12, 13]. NO then diffuses locally into associated smooth muscle cells and binds to an iron substrate contained within the heme moiety of guanylate cyclase [14], activating this enzyme to convert guanosine-5’-triphosphate (GTP) to cGMP [14]. The production of cGMP in turn activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (PKG), which then functions downstream to promote relaxation of corpus cavernosal smooth muscle, resulting in penile erection [12, 13, 15]. Erection is then terminated primarily through the activity of the cGMP-specific type 5 phosphodiesterase (PDE5) enzyme, which acts to hydrolyze the 3’5’ bonds of cGMP converting it to its inactive state 5’-GMP [16]. A delicate balance in guanylate cyclase and PDE5 activities is thus critical in order to maintain the steady-state concentrations of cGMP, and consequently, penile neurovascular homeostasis [17].

Fig. (1).

Schematic representation of the molecular pathophysiologic mechanisms of priapism; normal penile erection physiology depicted in inset (bottom right). A constellation of molecular factors promote uncontrolled erection (priapism) by interfering with the normal regulatory control mechanisms involved in the return of the penis back to its flaccid state. Circular arrows represent pathway between penile erection states. Horizontal black arrows represent mediation. Horizontal black T-shapes represent inhibition. Broken arrows represent both direct and indirect downstream effects of signaling pathways. Upward black arrows represent upregulation. Downward black arrows represent downregulation. NO/cGMP = nitric oxide/ cyclic guanosine monophosphate, ROS/RNS = reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species, ROCK = rho-associated protein kinase, PDE5 = phosphodiesterase type 5, HO = heme oxygenase

Molecular Mechanisms of Priapism Pathophysiology (Figure 1)

Nitric Oxide/cGMP and PDE5

Dysregulation of the NO/cGMP signaling pathway in the penis is thought to be the primary molecular mechanism of recurrent ischemic priapism [18]. Mouse models of eNOS deficiency (eNOS−/−), both eNOS and nNOS deficiency (eNOS−/−, nNOS−/−) (dNOS), and transgenic SCD mice have previously been shown to demonstrate a phenomenon of exaggerated erectile responses with stimulation of the cavernous nerve and penile fibrotic changes (i.e., increased collagen to smooth muscle ratio and hydroxyproline content) [15, 18, 19]. These studies identified transcriptional and translational down-regulation of PDE5, owing to basally decreased cGMP. Chronically decreased production of endothelium-derived NO and thus bioavailability were confirmed, providing a mechanism for these precise derangements occurring in the NO/cGMP signaling pathway [18–20].

SCD, a risk factor for RIP, represents a chronic state of decreased endothelium-derived NO bioavailability [21]. This NO reduction results from hemolysis which releases free hemoglobin into the circulation. Hemoglobin then avidly scavenges intravascular NO causing a decrease in normal levels [21, 22]. In addition to hemoglobin, arginase is also released during hemolysis. This enzyme functions to degrade L-arginine in the vasculature [21]. The presence of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their mediators have also been demonstrated to impair the function and formation of endothelium-derived NO [23, 24].

Loss of eNOS is another critical source of decreased NO bioavailability as it can be caused by the destruction of vascular endothelium resulting from ischemic priapism [25]. Functional impairment of eNOS may also occur through posttranslational modification, specifically at the Ser-1177 phosphorylation site. eNOS typically interacts with the positive protein regulator heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) [26] and this interaction increases with endothelial cell stimulation such as through shear stress [15, 27]. Protein kinase B (AKT) then binds to HSP90 in an adjacent region to eNOS through a calmodulin-mediated mechanism and facilitates the phosphorylation of eNOS at this Ser-1177 site [15]. However, decreased basal levels of activated eNOS have been demonstrated in the SCD mouse penis, resulting from decreased interactions between eNOS and HSP90 [28]. Thus, this chronically decreased activation of eNOS results in its decreased function in NO generation and is thought to be a source of PDE5 down-regulation.

Chronic decrease in endothelial NO production and bioavailability leads to a subsequent decrease in cGMP production and thus a compensatory reduction in cGMP-dependent transcription, expression and activity of PDE5 [18, 29]. With neurologically-initiated, erectogenic stimulation, which can occur with sexual activity or sleep, cGMP accumulates to promote cavernosal relaxation. However, due to reduced basal levels of PDE5, the normal regulatory mechanism of erection is deficient resulting in priapism (Figure 1).

RhoA/Rho- kinase

The RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) signal transduction pathway is the predominant vasoconstrictor pathway in the penis that maintains the organ in a flaccid state [30] [31]. This pathway influences erectile function in several ways, including vasoconstriction and regulation of eNOS [26, 30, 32]. Rho, a member of the Ras low molecular weight of GTP-binding proteins mediates agonist activation of ROCK [33]. ROCK 1 and ROCK2 are downstream effectors of the ROCK pathway. ROCK mediates its contractile effects through calcium independent promotion of light chain phosphorylation and inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase. Activated RhoA/ROCK has been shown to impair erectile function [34].

Dysregulated Rho signaling contributes to the pathophysiology of priapism. Bivalacqua et al reported that total ROCK activity in eNOS knock-out mice, which demonstrate a priapism phenotype, was reduced, with no change in RhoA activity [20]. Bivalacqua et al later reported attenuated RhoA/ROCK signaling in penes of transgenic SCD mice contributing to priapism [35]. Penes of SCD mice display a reduction in RhoA activity and specifically ROCK2 protein expression compared to that of the wild-type mouse penis. The ROCK2 isoform is the predominant isoform regulating smooth muscle contraction [36]. Investigations of the human SCD penis confirmed dysregulated Rho signaling with reduced RhoA expression [37]. It therefore appears that reduced RhoA/ROCK signaling leads to reduced vasoconstrictive activity in the penis in SCD, which increases the susceptibility of the penis to altered vasodilatory effects, contributing to priapism [15].

Adenosine

Adenosine, like NO has the unique properties of being a potent vasodilator and neurotransmitter with a very short half –life (<10 seconds) [38]. Adenosine is generated intracellularly and extracellularly by breakdown of adenine nucleotides. Intracellularly this is achieved by dephosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate (AMP) or hydrolysis of S-adenosyl-homocysteine [39]. Adenosine is metabolized by the enzymes adenosine kinase (ADK) and adenosine deaminase (ADA). ADA converts adenosine to inosine. Adenosine is formed extracellularly by the multistep conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is released by neurons under conditions of mechanical stress. Stressful conditions such as hypoxia, ischemia and cellular damage increase intracellular and extracellular levels of adenosine.

Adenosine elicits its effects on cells through the G protein-coupled receptors, ADORA1, ADORA2A, ADORA2B and ADORA3. ADORA2A and ADORA2B are coupled to adenylyl cyclase and increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [39]. The ADORA2B receptor has been recognized to be the receptor that mediates corpus cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation [40, 41]. Adenosine-induced cAMP production induces protein kinases A and G, which reduces calcium/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain phosphorylation and increases smooth muscle relaxation [42].

Early animal studies demonstrated the role of adenosine as a potent vasodilator and factor in normal erections [43]. Intracavernosal injection of adenosine increases pudendal arterial blood flow and intracavernosal pressure, and induces penile erections in dogs. This action is abrogated by treatment with a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, theophylline [44]. Further animal studies revealed that adenosine causes relaxation of the corpus cavernosum under baseline tension and pre-contraction [40, 41, 45–47]. Filippi et al were able to demonstrate relaxation of human corpus cavernosal tissue in response to adenosine [48].

Excessive adenosine signaling is a recognized pathophysiologic mechanism of priapism. Mi et al studied erectile function in ADA deficient (ada −/−) mice and also transgenic SCD mice [41]. Because of a lack of ADA, ada −/− mice demonstrate increased adenosine receptor signaling, as well as increased priapic activity and prolonged erections. Increased corporal smooth muscle relaxation, mediated through ADORAB receptor A2BR activation, was also observed in response to nerve stimulation. As is seen in humans with priapism, ada −/− mice have penile vascular damage and fibrosis after episodes of prolonged erections. Priapic activity is terminated by administration of polyethylene glycol modified ADA (PEG-ADA), an agent used in enzyme replacement therapy in patients with ADA by reducing the accumulation of adenosine [49, 50]. Similar phenotypic features of increased priapism and prolonged erections are predictably noted in SCD transgenic mice. Increased adenosine levels are also noted in penes of SCD mice. Similar to ada −/− mice, priapic activity in SCD mice is terminated after administration of PEG-ADA. These molecular findings have great clinical importance as men with priapism, particularly those with SCD, endure conditions of great stress such as hypoxia and ischemia, which enhances adenosine production. Therefore, under conditions of stress, not only is NO release deficient but also adenosine signaling is excessive, which may account for priapism.

Wen et al found that excessive adenosine signaling in ada−/− mice results in extensive penile corporal fibrosis, endothelial damage, intimal thickening and smooth muscle hypertrophy [51]. Transforming growth factor (TGF-β1) was found to be the signaling molecule responsible for the increased pro-collagenase expression noted in the setting of this fibrosis. Recently, Ning et al reported that in SCD and ADA −/− mice excessive adenosine signaling (via A2BR) reduces PDE5 gene expression and activity in a hypoxia-inducible factor -1α (Hif-1α) dependent manner [52]. The effects of increased adenosine signaling in priapism appear to potentiate those of NO dysfunction. Further studies in this area are encouraged.

Opiorphins

The opiorphin signaling pathway is a recently recognized potential mediator of cavernosal smooth muscle function, as it has been implicated in the excessive relaxation characterizing priapism [53]. This family of pentapeptides has been demonstrated to functionally inhibit neutral endopeptidases, which are involved in the metabolism of a diverse range of signaling peptides [53, 54] and prevent proteolysis of bound peptide agonists [55]. Investigations into the role of these pentapeptides began with the discovery of the down-regulated opiorphan homolog, variable coding sequence protein A1 (Vcsa1 or sialorphin), found in the rat submandibular gland, in animal models of erectile dysfunction [56]. Subsequently, down-regulation of human opiorphan homolog analogs, hSMR3A and ProL1, was also demonstrated in patients with erectile dysfunction [57, 58]. The genes encoding these opiorphin homologs have been found to be expressed significantly in submandibular gland, prostate, and penile smooth muscle [15].

Experimental gene transfer of opiorphin homologues in animal models has been shown to enhance the relaxation of corporal smooth muscle, improving erectile function in aged rats at lower doses and inducing a priapic-like condition at higher concentrations [56, 58, 59]. Using microarray analysis, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), an enzyme involved in the polyamine synthesis pathway, was identified as most significantly up-regulated in penile tissues of these animal models following overexpression of these genes [60]. Inhibition of ODC was found to prevent this experimentally-induced priapism, suggesting that this enzyme, when up-regulated, functions as a mediator of priapism [15, 60]. Additionally, in penile tissues eNOS and PDE5 gene expression levels are decreased while arginase 1 and 2 (enzymes involved in the polyamine synthesis) expression levels are increased. This molecular expression pattern was also found to be present in transgenic SCD mice along with up-regulation of the mouse homolog of ODC, verifying this condition in an animal model of priapism [15, 60]. Most recently, opiorphin has been shown to be a key regulator in the hypoxia-induced response associated with the priapic environment, as it was found to activate Hif-1a and A2BR, influential pathways involved in cavernous smooth muscle relaxation [53]. The systemic hypoxia that occurs in SCD may offer a setting through which this pathway may manifest priapism.

In this mechanism of priapism, up-regulation of ODC and decreased expression of arginase 1 and 2 may be indicative of L-arginine shunting from the NO/cGMP pathway for NO production and instead to the polyamine pathway [54]. As such, dysregulation in the opiorphin signaling pathway may function to decrease NO bioavailability and thus create a derangement in NO balance, promoting the mechanism of priapism involving NO/cGMP pathway dysregulation.

Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress

Anti-oxidant enzymes and scavengers of oxygen radicals such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, maintain homeostatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels under normal physiologic conditions. In the setting of chronic oxidative stress, such as that present in SCD, this balance is lost and the production of ROS can no longer be adequately managed by these regulatory mechanisms [61]. Several enzymes have been identified as major contributors to ROS and reactive nitrosative species (RNS) production, including xanthine oxidase (XO) and NADPH oxidase, and even NOS through actions of its inducible form and uncoupling of its endothelial form [61, 62]. Increased sources of oxidative stress, as measured by elevated levels of NADPH oxidase subunits, have been demonstrated in both transgenic SCD mice and human priapic penile tissue [37, 63]. Additionally, increased markers of oxidative stress and activation of protein degradation pathways have also been demonstrated in corporal tissues of animal models of priapism [64]. Both ROS, including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, and RNS, including peroxynitrite and S-nitrosothiols, contribute to the cavernosal tissue damage of priapism in association with penile reperfusion injury that occurs during the period of ischemia relief that follows priapism episodes [65].

Oxidative/nitrosative stress is not only a product of the reperfusion injury during relief of cavernosal ischemia, but it also plays a role in the generation of ischemic priapism [54]. Reactive species, specifically superoxide, function to decrease NO bioavailability by reacting with NO to produce peroxynitrite which then leads to the oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential cofactor for normal endothelial NO production [61]. Uncoupling of eNOS results from this limited bioavailability of the reduced form of BH4, and preferentially, leads to production of superoxide instead of NO [61]. Consequently, this oxidative environment becomes self-perpetuating. This source of decreasing NO bioavailability offers an additional mechanism for the NO/cGMP pathway derangement that is thought to underlie priapism.

Heme Oxygenase

Heme oxygenase (HO) is a critical enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of heme, a vasculotoxic and oxidative breakdown product of hemoglobin, to bilverdin, iron, and carbon monoxide (CO) [66–68]. HO exists as three isoforms: HO-1, an inducible form, ubiquitously present in endothelium and smooth muscle, that reacts to a variety of stress mediators such as heat and NO donors; HO-2, a constitutive form; and HO-3, which is not expressed in humans [66, 67]. Among other roles, HO-1 is thought to have antioxidant properties as it is up-regulated in vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardiac tissue in settings of hypoxia [66, 68]. HO-1 up-regulation has also been observed in cavernosal tissues of artificially-induced, animal priapic models [66]. This effect of HO-1 induction was shown to be local and time-dependent, with activity gradually increasing in time intervals evaluated from 0 to 24 hours [66].

This protective mechanism during cellular hypoxia is thought to be facilitated by interactions between the HO and NO/cGMP pathways [54]. Specifically, the resulting CO produced from the HO reaction has been shown to promote relaxation in stimulated human cavernosal tissues [66]. CO can stimulate soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) in the setting of decreased NO bioavailability, resulting in increased cGMP production; however, CO can also inhibit sGC in the presence of high NO levels [67]. Additionally, NO has also been reported to indirectly regulate the activity of HO [67]. Because the interaction between these two pathways is quite complex and incompletely understood, it is uncertain whether the up-regulation of HO-1 is a response to tissue hypoxia or an alternative induction mechanism of priapism [54].

Testosterone (Hormones)

The role of testosterone in regulating normal erections is well described [69]. Androgens maintain the function and structure of ganglionic nerves supplying the penis [70]. Androgens also maintain the integrity of corporal smooth muscle [15]. Androgens importantly regulate the molecular substances involved in normal erections, such as NOS and PDE5 expressions [71, 72]. Testosterone deficiency reduces amounts of these molecules and testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) restores them to normal levels, improving erections [71, 72].

The role of high circulating levels of testosterone has traditionally been thought to be facilitatory or causative in the pathophysiologic mechanism of priapism. Several medical case reports have, even recently, documented priapism episodes in association with TRT in hypogonadal males [73–75]. However, these cases of priapism have all occurred with use of intramuscular testosterone esters that result in supra-physiologic levels of testosterone [76]. The sporadic and infrequent occurrence of these cases questions the association of the priapism episodes and TRT. In fact, Burnett et al reported no association between priapism episodes and TRT in men using AndroGel, a commonly prescribed agent in hypogonadal males [76]. In 283 men investigated in 3 trials, no episode of priapism was reported. Post marketing data reported 8 cases of priapism in 40 million units of the drug sold, emphasizing the infrequency of the association.

In the SCD population, known to be at high risk of developing priapism, caution has always been given in administering TRT for fear of inducing priapism. This fear was substantiated by several case reports [77, 78]. However, Morrison et al administered TRT (testosterone undecanoate) to 7 men with SCD and hypogonadism who had varying frequencies of priapism, to achieve a eugonadal status [79]. TRT reduced, rather than enhanced, the frequency of episodes in SCD patients, and it also improved sexual function. The SCD model provides the perfect avenue to question the association of high circulating testosterone levels as a cause of priapism. Both testosterone deficiency and priapism are common in the SCD population [80, 81]. Therefore, it appears contradictory to perceive that high circulating testosterone levels are causative of priapism. In hypogonadism, molecular modulation of NOS and PDE5 is affected [82]. It is theorized that since molecular signaling of NO/PDE5/c GMP is aberrant in men with SCD and priapism, hypogonadism further exacerbates these molecular disturbances leading to priapism [79]. A recent study showed that transgenic SCD mice with low systemic testosterone had reduction of their priapism tendencies with testosterone administration (Burnett, unpublished study). Therefore, it is possible that low and not high serum testosterone levels may facilitate or cause priapism episodes, particularly in SCD.

Priapism Treatment

Effectors of the Adrenergic System

Intracavernosal sympathomimetics are currently employed in the treatment of ischemic priapism episodes, particularly in instances of failure of initial clinical aspiration and saline irrigation attempts, and also acutely as needed by patient self-injection for termination of the relatively shorter RIP episodes [7, 8]. On local injection, these agents function to cause alpha-adrenergic-mediated vasoconstriction through contractile stimulation of cavernous smooth muscle, resulting in detumescence [83]. Many available agents often have cardiac inotropic and chronotropic side-effects via beta-adrenergic stimulation. Accordingly, phenylephrine is typically the agent of choice due to its minimal beta-adrenergic stimulatory effects [7, 83].

The use of oral adrenergic agents has also been explored. One such agent, terbutaline, functions as a beta2-agonist and has demonstrated sporadic success [84]. Pseudoephedrine and ephedrine, two alkaloid-based oral agents, have also been studied, although they demonstrate a wide side-effect profile due to their receptor non-selectivity [85]. Oral therapies have generally been shown to have low efficacy in achieving detumescence [84]. Although adrenergic therapies are generally effective in locally treating priapism episodes, their roles are likely limited as preventative agents because they do not address the underlying pathophysiology of priapism [86]. The Priapism in Sickle Cell Study (PISCES), the largest randomized trial investigating the prevention of recurrent episodes, failed to demonstrate a difference in the number of weekly episodes between groups receiving ephedrine, etilefrine, or placebo. However, the study was limited by poor recruitment and a high attrition rate [87]. Although the findings from this study indicate a lack of efficacy with oral adrenergic therapies in priapism prophylaxis, further evaluations are warranted based on cavernosal tissue contractile responsiveness to alpha-agonists [54].

Effectors of the Nitrergic System

PDE5 Inhibitors

The devastating consequences of RIP fueled the search for an effective mechanism-based agent to prevent this disorder. In an SCD mouse model, PDE5 inhibitor treatment was discovered to reduce priapism episodes and restore PDE5 gene activity [88]. Although the application of PDE5 inhibitors for managing priapism would appear paradoxical to its well described erectogenic properties, the therapeutic mechanism involves re-establishing basal levels of cGMP in the penis which re-sets the levels of PDE5 expression and activity [89]. Therefore, chronic and continuous PDE5 inhibitor treatment reverses the NO signaling dysfunction seen in priapism. This discovery led to the first published case series of mechanism-based treatment of priapism. Four patients with RIP (3 associated with SCD and 1 identified as idiopathic) received long-term treatment with PDE5 inhibitors, which successfully alleviated RIP episodes [89]. This initial success was followed by a further study with follow-up of 7 patients with RIP (4 with SCD and 3 as idiopathic) for a period of 2 years, in whom chronic continuous PDE5 inhibitor treatment alleviated or resolved priapism episodes in 6 of 7 patients [90]. Patients were medicated in the morning after awakening and unassociated with sexual stimulation with sildenafil 25 mg daily with the option of increasing this dose to 50mg or converting to tadalafil 5 or 10 mg daily. The treatment was tolerable with no adverse effects and erectile function was maintained. Success was deemed to be poor in 1 patient due to the severity of his episodes and poor effect of PDE5 inhibitor therapy. Chronic PDE5 inhibitor treatment was therefore considered to be an effective and tolerable treatment for mild-moderately severe priapism. Similar effects were seen in a 19 year old patient with thalassemia intermedia and RIP, in whom priapism episodes were significantly reduced and erectile function remained intact after 2 months of chronic PDE5 inhibitor treatment and 6 months post-cessation [91]. Chronic PDE5 inhibitor therapy has also demonstrated effectiveness where anti-androgenic hormonal agents have been ineffective [82]. However, increased vaso-occlusive episodes were noted in a single case report involving a patient treated with chronic PDE5 inhibitor therapy for SCD-induced priapism [92]. This adverse effect had not been reported in previous case series and cautioned use of the agents in further trials.

The successful use of chronic PDE5 inhibitor therapy in priapism led to the commencement of a randomized controlled clinical trial to determine the safety and efficacy of sildenafil for priapism prevention [93]. Thirteen patients with frequent RIP episodes (> 2 per week) were randomized to sildenafil 50 mg daily or placebo for 8 weeks followed by open-label sildenafil for a further 8 weeks. Though priapism frequency reduction by 50% did not occur between the 2 study arms by intention-to-treat or per protocol analysis, during open-label assessment, 5 of 8 patients by intention-to-treat and 2 of 3 patients by per protocol analysis had met the primary outcome. No significant adverse effects differences were found between the 2 groups [93]. The trial was landmark, being the only controlled clinical trial commissioned to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PDE5 inhibitor therapy for RIP prevention.

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is an S-phase specific agent that blocks DNA synthesis. The drug remains the only FDA approved agent for SCD and has demonstrated clinical benefit in reducing painful crises and prolonging life in SCD patients [94, 95]. Initial case reports suggested a benefit of hydroxyurea administration for prevention of RIP [96, 97]. Anele et al recently reported on erectile function recovery in a patient with SCD after a prolonged episode of priapism and administration of hydroxyurea [98]. The proposed mechanism of action of hydroxyurea involves its role as an NO donor, as it reacts with hemoglobin to form NO, correcting the reduced bioavailability of NO seen in RIP [99, 100]. The ability of hydroxyurea to induce fetal hemoglobin and reduce hemolysis may further correct the reduced NO bioavailability of severe hemolysis [101]. The recovery of erectile function with use of hydroxyurea after the patient developed erectile dysfunction is thought to be due to its down-regulatory effect on endothelin-1 (ET-1), a pro-fibrotic molecule with a likely role in the corporal fibrosis associated with priapism [98, 102–104]. Because hydroxyurea is associated with the adverse effects of leg ulcers and oligospermia, safety concerns exist with the use of this therapy [105]. Further study of the potential benefit of this agent in priapism prevention is necessary.

Hormonal Modulators

Androgens play a critical role in erectile physiology, notably regulating the expression of the NOS isoforms in corporal smooth muscle [106]. Anti-androgen therapy functions along the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to cause suppression of associated mechanisms thought to be involved in promoting erections [54]. Ablative agents such as anti-androgens, which act to block androgen binding or production, as well as tropic and trophic analogues, which can downregulate pituitary gland function or decrease serum testosterone through negative feedback, have demonstrated effectiveness in single case reports and small studies [84, 107–113].

In the first trial of its kind, Serjeant et al described successful prevention of stuttering episodes using the estrogen receptor agonist, diethylstilbestrol, compared to placebo in a small sample of patients [109]. However, conclusions regarding this treatment’s efficacy could not be made based on the inferior quality of the study [114]. Another treatment described in successful episode prevention, ketoconazole, is an antifungal medication with antiandrogenic effects [107, 112]. This agent functions to inhibit the cytochrome-P450 enzyme, 14-alpha-demethylase, preventing the conversion of lanosterol into ergosterol in the sterol biosynthesis pathway and consequently reducing testosterone production in the testes and adrenal glands [84]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues have also been reported to be effective through downstream reduction of androgen production [111]. Chronic androgen ablation has also been demonstrated to induce ED through mechanisms involving decreased activation of eNOS, nNOS, and PDE5; dysfunction and loss of cavernosal smooth muscle cells; and increased expression of RhoA and Rho-kinase in cavernosal tissues [72, 84, 106]. Furthermore, despite these androgen ablative effects, such hormonal modulators are not always successful in preventing recurrent episodes and their use is often at the expense of substantial side effects including decreased libido, gynecomastia, delayed growth/development (particularly in boys), and even potential cardiovascular and metabolic effects [8, 54, 115]. Thus, conventional anti-androgen therapies for priapism may effectively hamper erectile tissue structure and function, exerting a non-specific management approach for this condition.

The role of androgens in treating recurrent priapism is not entirely known. Although TRT has commonly been thought to precipitate episodes in isolated case reports, recent clinical studies have failed to identify such an association [76, 79]. Additionally, elevated testosterone levels have never been demonstrated in patients with recurrent priapism. Rather, new theories suggest that testosterone therapy may actually function to restore erectile physiology through the mechanisms involving NO regulation and balance [106]. In a study evaluating the use of chronic finasteride, a type-2 5-alpha reductase inhibitor involved in inhibiting the conversion of dihydrotestosterone from testosterone, Rachid-Filho et al demonstrated success in its use for priapism episode prophylaxis among patients with SCD [116]. Although contrary to current dogma, a possible mechanism of this therapeutic success may involve maintenance of testosterone levels that support normal erectile mechanisms and function [54]. As such, further investigations into the function of androgens and their therapeutic replacement in the setting of recurrent episodes are warranted.

New and Emerging Agents

Pentoxifylline

The ability of an agent to reduce corporal fibrosis associated with prolonged episodes of ischemic priapism would be beneficial as this could theoretically improve erectile function. Pentoxifylline is a hemorrheologic agent that reduces fibrosis and TGF-β mediated deposition of collagen in the tunica albuginea [117]. This agent had facilitated recovery of erections in a rat model of erectile dysfunction post prostatectomy [118]. In a recent study, pentoxifylline was able to reduce collagen density in an ischemic-induced priapism rat model [119]. The potential benefits of an agent with such an effect are great and this agent requires further studies.

Sustained NO- releasing compound

1, 5-Bis-(dihexyl-N-nitrosoamino)-2, 4-dinitrobenzene (C6'), a sustained NO- releasing compound and an inactive form of the compound [1, 5-bis-(dihexylamino)-2, 4-dinitrobenzene (C6)], was recently investigated for its therapeutic effects on the molecular mechanisms underlying priapism [120]. The effects of this agent were evaluated in dNOS and transgenic SCD mice demonstrating a priapic phenotype. C6’ generated NO, increased cGMP, reversed abnormalities in PDE5 function, and reversed the phenotypic changes of priapism. This work provides a proof of principle for the use of sustained NO supplementation in managing recurrent priapism.

Adenosine Deaminase Enzyme Therapy

Previously reported animal studies have shown the benefit of PEG-ADA therapy in reversing elevated adenosine levels and the priapic phenotype in animal models. PEG-ADA is a generally tolerated and efficacious agent when used in persons with congenital deficiency of ADA [121]. Wen et al found that Ada −/− mice that were treated with high doses of PEG-ADA, which lowered levels of adenosine in penile tissues, had neither obvious vascular damage nor evidence of penile fibrosis. Wen et al further sought to investigate the therapeutic effects of ADA enzyme therapy on reversing priapism in SCD and ada −/− mice [121]. Both mouse models were treated with varying doses of PEG-ADA, and both adenosine levels in the penis and corporal cavernosal smooth muscle contractility were measured. When treated with PEG-ADA, SCD and ada −/− mice were found to have reduced electric-field stimulated (EFS)-induced corporal relaxation. This finding suggested the potential role of this class of therapeutic agents in humans with priapism. This novel approach to treatment of priapism is encouraging and warrants further studies.

Conclusion

Ongoing studies have provided increasing information regarding the pathophysiology of priapism and have promoted an understanding of the interplay of several molecular factors. This progress has resulted in basic scientific data suggesting potential therapeutic agents targeting deranged NO/cGMP pathway signaling, increased adenosine signaling, upregulated opiorphin signaling pathway, and abnormal testosterone serum levels. Chronic PDE5 inhibitor therapy has been studied in a controlled clinical trial, demonstrating some efficacy in ameliorating RIP. Clinical use of other therapies, such as hormonal modulators, has also shown some success in decreasing priapism episodes. However, they have lacked rigorous evaluation through controlled trials and are accompanied by significant side effects. More recent pre-clinical studies provide evidence of the benefits of an NO-donor and ADA enzyme therapy in reducing priapism episodes and pentoxifylline in reducing corporal fibrosis associated with priapism. Further exploration and understanding of these multiple molecular pathways and their interactions will contribute toward uncovering new potential targets and foster subsequent therapeutic options for the treatment and prevention of this devastating condition.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;170(4 Pt 1):1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000087608.07371.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulmala RV, Lehtonen TA, Tammela TL. Priapism, its incidence and seasonal distribution in Finland. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29(1):93–96. doi: 10.3109/00365599509180545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MJ. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57(5):970–972. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantadakis E, Cavender JD, Rogers ZR, Ewalt DH, Buchanan GR. Prevalence of priapism in children and adolescents with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21(6):518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140(11):1434–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeyoju AB, Olujohungbe AB, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications - an international multicentre study. BJU Int. 2002;90(9):898–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison BF, Burnett AL. Priapism in hematological and coagulative disorders: an update. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8(4):223–230. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spycher MA, Hauri D. The ultrastructure of the erectile tissue in priapism. J Urol. 1986;135(1):142–147. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45549-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addis G, Spector R, Shaw E, Musumadi L, Dhanda C. The physical, social and psychological impact of priapism on adult males with sickle cell disorder. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(2):145–154. doi: 10.1177/1742395307081505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurt KJ, Musicki B, Palese MA, et al. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase mediates penile erection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(6):4061–4066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052712499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett AL, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, Chang TS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257(5068):401–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajfer J, Aronson WJ, Bush PA, Dorey FJ, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide as a mediator of relaxation of the corpus cavernosum in response to nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurotransmission. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(2):90–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201093260203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ignarro LJ. Haem-dependent activation of guanylate cyclase and cyclic GMP formation by endogenous nitric oxide: a unique transduction mechanism for transcellular signaling. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;67(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Kutlu O, Burnett AL. New insights into the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease-associated priapism. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):79–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin JD, Francis SH. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase-5: target of sildenafil. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(20):13729–13732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbin JD. Mechanisms of action of PDE5 inhibition in erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S4–S7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, Takimoto E, Kass DA, Burnett AL. Phosphodiesterase-5A dysregulation in penile erectile tissue is a mechanism of priapism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(5):1661–1666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407183102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT, Burnett AL, Champion HC. Establishment of a transgenic sickle-cell mouse model to study the pathophysiology of priapism. J Sex Med. 2009;6(9):2494–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bivalacqua TJ, Liu T, Musicki B, Champion HC, Burnett AL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase keeps erection regulatory function balance in the penis. Eur Urol. 2007;51(6):1732–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akinsheye I, Klings ES. Sickle cell anemia and vascular dysfunction: the nitric oxide connection. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224(3):620–625. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, et al. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med. 2002;8(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houston M, Estevez A, Chumley P, et al. Binding of xanthine oxidase to vascular endothelium. Kinetic characterization and oxidative impairment of nitric oxide-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(8):4985–4994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Adler B, et al. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15215–15220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(9):618–625. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musicki B, Ross AE, Champion HC, Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Posttranslational modification of constitutive nitric oxide synthase in the penis. J Androl. 2009;30(4):352–362. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudzinski DM, Michel T. Life history of eNOS: partners and pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(2):247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musicki B, Champion HC, Hsu LL, Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL. Post-translational inactivation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the transgenic sickle cell mouse penis. J Sex Med. 2011;8(2):419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin CS, Chow S, Lau A, Tu R, Lue TF. Human PDE5A gene encodes three PDE5 isoforms from two alternate promoters. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14(1):15–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Clinton Webb R, et al. Antagonism of Rho-kinase stimulates rat penile erection via a nitric oxide-independent pathway. Nat Med. 2001;7(1):119–122. doi: 10.1038/83258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Eto M, Steers WD, Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. RhoA-mediated Ca2+ sensitization in erectile function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(34):30614–30621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Usta MF, et al. RhoA/Rho-kinase suppresses endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the penis: a mechanism for diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(24):9121–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400520101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa O, Fujisawa K, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Nakao K, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett. 1996;392(2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gratzke C, Strong TD, Gebska MA, et al. Activated RhoA/Rho kinase impairs erectile function after cavernous nerve injury in rats. J Urol. 2010;184(5):2197–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bivalacqua TJ, Ross AE, Strong TD, et al. Attenuated RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in penis of transgenic sickle cell mice. Urology. 2010;76(2):510 e7–510 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Zheng XR, Riddick N, et al. ROCK isoform regulation of myosin phosphatase and contractility in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2009;104(4):531–540. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagoda G, Sezen SF, Cabrini MR, Musicki B, Burnett AL. Molecular analysis of erection regulatory factors in sickle cell disease associated priapism in the human penis. J Urol. 2013;189(2):762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patole S, Lee J, Buettner P, Whitehall J. Improved oxygenation following adenosine infusion in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Biol Neonate. 1998;74(5):345–350. doi: 10.1159/000014052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fredholm BB, AP IJ, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(4):527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang PH, Wu SN, Tsai EM, et al. Adenosine modulation of neurotransmission in penile erection. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;38(4):357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mi T, Abbasi S, Zhang H, et al. Excess adenosine in murine penile erectile tissues contributes to priapism via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(4):1491–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI33467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin CS, Lin G, Lue TF. Cyclic nucleotide signaling in cavernous smooth muscle. J Sex Med. 2005;2(4):478–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi Y, Ishii N, Lue TF, Tanagho EA. Pharmacological effects of adenosine on canine penile erection. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1991;165(1):49–58. doi: 10.1620/tjem.165.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi Y, Ishii N, Lue TF, Tanagho EA. Effects of adenosine on canine penile erection. J Urol. 1992;148(4):1323–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36901-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu HY, Broderick GA, Suh JK, Hypolite JA, Levin RM. Effects of purines on rabbit corpus cavernosum contractile activity. Int J Impot Res. 1993;5(3):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Filippi S, Amerini S, Maggi M, Natali A, Ledda F. Studies on the mechanisms involved in the ATP-induced relaxation in human and rabbit corpus cavernosum. J Urol. 1999;161(1):326–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tostes RC, Giachini FR, Carneiro FS, Leite R, Inscho EW, Webb RC. Determination of adenosine effects and adenosine receptors in murine corpus cavernosum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(2):678–685. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Filippi S, Mancini M, Amerini S, et al. Functional adenosine receptors in human corpora cavernosa. Int J Androl. 2000;23(4):210–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2000.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hershfield MS, Buckley RH, Greenberg ML, et al. Treatment of adenosine deaminase deficiency with polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(10):589–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703053161005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levy Y, Hershfield MS, Fernandez-Mejia C, et al. Adenosine deaminase deficiency with late onset of recurrent infections: response to treatment with polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase. J Pediatr. 1988;113(2):312–317. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, et al. Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. FASEB J. 2010;24(3):740–749. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ning C, Wen J, Zhang Y, et al. Excess adenosine A2B receptor signaling contributes to priapism through HIF-1alpha mediated reduction of PDE5 gene expression. FASEB J. 2014;28(6):2725–2735. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-247833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu S, Tar MT, Melman A, Davies KP. Opiorphin is a master regulator of the hypoxic response in corporal smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 2014;28(8):3633–3644. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrison BF, Burnett AL. Stuttering priapism: insights into pathogenesis and management. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(4):268–276. doi: 10.1007/s11934-012-0258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wisner A, Dufour E, Messaoudi M, et al. Human Opiorphin, a natural antinociceptive modulator of opioid-dependent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(47):17979–17984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605865103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong Y, Tar M, Davelman F, Christ G, Melman A, Davies KP. Variable coding sequence protein A1 as a marker for erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2006;98(2):396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tong Y, Tar M, Monrose V, DiSanto M, Melman A, Davies KP. hSMR3A as a marker for patients with erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2007;178(1):338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tong Y, Tar M, Melman A, Davies K. The opiorphin gene (ProL1) and its homologues function in erectile physiology. BJU Int. 2008;102(6):736–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davies KP, Tar M, Rougeot C, Melman A. Sialorphin (the mature peptide product of Vcsa1) relaxes corporal smooth muscle tissue and increases erectile function in the ageing rat. BJU Int. 2007;99(2):431–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanika ND, Tar M, Tong Y, Kuppam DS, Melman A, Davies KP. The mechanism of opiorphin-induced experimental priapism in rats involves activation of the polyamine synthetic pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297(4):C916–C927. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00656.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood KC, Granger DN. Sickle cell disease: role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen metabolites. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34(9):926–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burnett AL, Musicki B, Jin L, Bivalacqua TJ. Nitric oxide/redox-based signalling as a therapeutic target for penile disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10(3):445–457. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Musicki B, Liu T, Sezen SF, Burnett AL. Targeting NADPH oxidase decreases oxidative stress in the transgenic sickle cell mouse penis. J Sex Med. 2012;9(8):1980–1987. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanika ND, Melman A, Davies KP. Experimental priapism is associated with increased oxidative stress and activation of protein degradation pathways in corporal tissue. Int J Impot Res. 2010;22(6):363–373. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Munarriz R, Park K, Huang YH, et al. Reperfusion of ischemic corporal tissue: physiologic and biochemical changes in an animal model of ischemic priapism. Urology. 2003;62(4):760–764. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin YC, Gam SC, Jung JH, Hyun JS, Chang KC, Hyun JS. Expression and activity of heme oxygenase-1 in artificially induced low-flow priapism in rat penile tissues. J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1876–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shamloul R. The potential role of the heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide system in male sexual dysfunctions. J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):324–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT. Evolution of novel small-molecule therapeutics targeting sickle cell vasculopathy. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2638–2646. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saad F, Grahl AS, Aversa A, et al. Effects of testosterone on erectile function: implications for the therapy of erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2007;99(5):988–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meusburger SM, Keast JR. Testosterone and nerve growth factor have distinct but interacting effects on structure and neurotransmitter expression of adult pelvic ganglion cells in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;108(2):331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zvara P, Sioufi R, Schipper HM, Begin LR, Brock GB. Nitric oxide mediated erectile activity is a testosterone dependent event: a rat erection model. Int J Impot Res. 1995;7(4):209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morelli A, Filippi S, Mancina R, et al. Androgens regulate phosphodiesterase type 5 expression and functional activity in corpora cavernosa. Endocrinology. 2004;145(5):2253–2263. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donaldson JF, Davis N, Davies JH, Rees RW, Steinbrecher HA. Priapism in teenage boys following depot testosterone. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(11–12):1173–1176. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ichioka K, Utsunomiya N, Kohei N, Ueda N, Inoue K, Terai A. Testosterone-induced priapism in Klinefelter syndrome. Urology. 2006;67(3):622 e17–622 e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shergill IS, Pranesh N, Hamid R, Arya M, Anjum I. Testosterone induced priapism in Kallmann's syndrome. J Urol. 2003;169(3):1089. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000049199.37765.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burnett AL, Kan-Dobrosky N, Miller MG. Testosterone replacement with 1% testosterone gel and priapism: no definite risk relationship. J Sex Med. 2013;10(4):1151–1161. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Slayton W, Kedar A, Schatz D. Testosterone induced priapism in two adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1995;8(3):199–203. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1995.8.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lundh B, Gardner FH. The haematological response to androgens in sickle cell anaemia. Scand J Haematol. 1970;7(5):389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1970.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morrison BF, Reid M, Madden W, Burnett AL. Testosterone replacement therapy does not promote priapism in hypogonadal men with sickle cell disease: 12-month safety report. Andrology. 2013;1(4):576–582. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abbasi AA, Prasad AS, Ortega J, Congco E, Oberleas D. Gonadal function abnormalities in sickle cell anemia. Studies in adult male patients. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85(5):601–605. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Osegbe DN, Akinyanju OO. Testicular dysfunction in men with sickle cell disease. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63(736):95–98. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.63.736.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pierorazio PM, Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL. Daily phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy as rescue for recurrent ischemic priapism after failed androgen ablation. J Androl. 2011;32(4):371–374. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.011890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song PH, Moon KH. Priapism: current updates in clinical management. Korean J Urol. 2013;54(12):816–823. doi: 10.4111/kju.2013.54.12.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuan J, Desouza R, Westney OL, Wang R. Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism. Asian J Androl. 2008;10(1):88–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Olujohungbe A, Burnett AL. How I manage priapism due to sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(6):754–765. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kovac JR, Mak SK, Garcia MM, Lue TF. A pathophysiology-based approach to the management of early priapism. Asian J Androl. 2013;15(1):20–26. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Olujohungbe AB, Adeyoju A, Yardumian A, et al. A prospective diary study of stuttering priapism in adolescents and young men with sickle cell anemia: report of an international randomized control trial--the priapism in sickle cell study. J Androl. 2011;32(4):375–382. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.010934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Hsu LL, Berkowitz DE, Champion HC, Burnett AL. Sildenafil citrate-restored eNOS and PDE5 regulation in sickle cell mouse penis prevents priapism via control of oxidative/nitrosative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Long-term oral phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor therapy alleviates recurrent priapism. Urology. 2006;67(5):1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Feasibility of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in a pharmacologic prevention program for recurrent priapism. J Sex Med. 2006;3(6):1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tzortzis V, Mitrakas L, Gravas S, et al. Oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors alleviate recurrent priapism complicating thalassemia intermedia: a case report. J Sex Med. 2009;6(7):2068–2071. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lane A, Deveras R. Potential risks of chronic sildenafil use for priapism in sickle cell disease. J Sex Med. 2011;8(11):3193–3195. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burnett AL, Anele UA, Trueheart IN, Strouse JJ, Casella JF. Randomized controlled trial of sildenafil for preventing recurrent ischemic priapism in sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):664–668. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003;289(13):1645–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steinberg MH, McCarthy WF, Castro O, et al. The risks and benefits of long-term use of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: A 17.5 year follow-up. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(6):403–408. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Saad ST, Lajolo C, Gilli S, et al. Follow-up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2004;77(1):45–49. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Al Jam'a AH, Al Dabbous IA. Hydroxyurea in the treatment of sickle cell associated priapism. J Urol. 1998;159(5):1642. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Anele UA, Kyle Mack A, Resar LM, Burnett AL. Hydroxyurea therapy for priapism prevention and erectile function recovery in sickle cell disease: a case report and review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(9):1733–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cokic VP, Beleslin-Cokic BB, Tomic M, Stojilkovic SS, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN. Hydroxyurea induces the eNOS-cGMP pathway in endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;108(1):184–191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gladwin MT, Shelhamer JH, Ognibene FP, et al. Nitric oxide donor properties of hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;116(2):436–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2010;115(26):5300–5311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-146852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brun M, Bourdoulous S, Couraud PO, Elion J, Krishnamoorthy R, Lapoumeroulie C. Hydroxyurea downregulates endothelin-1 gene expression and upregulates ICAM-1 gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3(4):215–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lapoumeroulie C, Benkerrou M, Odievre MH, Ducrocq R, Brun M, Elion J. Decreased plasma endothelin-1 levels in children with sickle cell disease treated with hydroxyurea. Haematologica. 2005;90(3):401–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shi-Wen X, Chen Y, Denton CP, et al. Endothelin-1 promotes myofibroblast induction through the ETA receptor via a rac/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway and is essential for the enhanced contractile phenotype of fibrotic fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(6):2707–2719. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Salonia A, Eardley I, Giuliano F, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on priapism. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Traish A, Kim N. The physiological role of androgens in penile erection: regulation of corpus cavernosum structure and function. J Sex Med. 2005;2(6):759–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Abern MR, Levine LA. Ketoconazole and prednisone to prevent recurrent ischemic priapism. J Urol. 2009;182(4):1401–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dahm P, Rao DS, Donatucci CF. Antiandrogens in the treatment of priapism. Urology. 2002;59(1):138. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Serjeant GR, de Ceulaer K, Maude GH. Stilboestrol and stuttering priapism in homozygous sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 1985;2(8467):1274–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shamloul R, el Nashaar A. Idiopathic stuttering priapism treated successfully with low-dose ethinyl estradiol: a single case report. J Sex Med. 2005;2(5):732–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Steinberg J, Eyre RC. Management of recurrent priapism with epinephrine self-injection and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue. J Urol. 1995;153(1):152–153. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199501000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hoeh MP, Levine LA. Prevention of recurrent ischemic priapism with ketoconazole: evolution of a treatment protocol and patient outcomes. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):197–204. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yamashita N, Hisasue S, Kato R, et al. Idiopathic stuttering priapism: recovery of detumescence mechanism with temporal use of antiandrogen. Urology. 2004;63(6):1182–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chinegwundoh F, Anie KA. Treatments for priapism in boys and men with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD004198. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004198.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Singhal A, Gabay L, Serjeant GR. Testosterone deficiency and extreme retardation of puberty in homozygous sickle-cell disease. West Indian Med J. 1995;44(1):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rachid-Filho D, Cavalcanti AG, Favorito LA, Costa WS, Sampaio FJ. Treatment of recurrent priapism in sickle cell anemia with finasteride: a new approach. Urology. 2009;74(5):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shindel AW, Lin G, Ning H, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-stimulated collagen deposition and elastogenesis in human tunica albuginea-derived fibroblasts part 1: impact on extracellular matrix. J Sex Med. 2010;7(6):2077–2085. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Albersen M, Fandel TM, Zhang H, et al. Pentoxifylline promotes recovery of erectile function in a rat model of postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2011;59(2):286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Erdemir F, Firat F, Markoc F, et al. The effect of pentoxifylline on penile cavernosal tissues in ischemic priapism-induced rat model. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0769-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lagoda G, Sezen SF, Hurt KJ, Cabrini MR, Mohanty DK, Burnett AL. Sustained nitric oxide (NO)-releasing compound reverses dysregulated NO signal transduction in priapism. FASEB J. 2014;28(1):76–84. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, et al. Adenosine deaminase enzyme therapy prevents and reverses the heightened cavernosal relaxation in priapism. J Sex Med. 2010;7(9):3011–3022. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]