Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with cardiovascular dysfunction. We evaluated the role of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in vascular endothelial function, a marker of cardiovascular health, at baseline and in the presence of angiotensin II, using an endothelial-specific knockout of the murine VDR gene. In the absence of endothelial VDR, acetylcholine-induced aortic relaxation was significantly impaired (maximal relaxation, endothelial-specific VDR knockout =58% vs. control=73%, p<0.05). This was accompanied by a reduction in eNOS expression and phospho-vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein levels in aortae from the endothelial-specific VDR knockout vs. control mice. While blood pressure levels at baseline were comparable at 12 and 24 weeks of age, the endothelial VDR knockout mice demonstrated increased sensitivity to the hypertensive effects of angiotensin II compared to control mice (after 1-week infusion: knockout = 155±15 mmHg vs. control = 133±7 mmHg, p<0.01; after 2-week infusion: knockout = 164±9 mmHg vs. control = 152±13 mmHg, p<0.05). By the end of two weeks, angiotensin II infusion-induced, hypertrophy-sensitive myocardial gene expression was higher in endothelial-specific VDR knockout mice (fold change compared to saline-infused control mice, ANP: knockout mice = 3.12 vs. control= 1.7, p<0.05; BNP: knockout mice= 4.72 vs. control= 2.68, p<0.05). These results suggest that endothelial VDR plays an important role in endothelial cell function and blood pressure control and imply a potential role for VDR agonists in the management of cardiovascular disease associated with endothelial dysfunction.

Keywords: vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, gene targeting, endothelial dysfunction, hypertension

Introduction

Vitamin D, or cholecalciferol, is a lipophilic, secosteroid hormone. Vitamin D levels are maintained either through dietary consumption or through de novo synthesis in the basal layers of the epidermis following exposure to ultraviolet light. Vitamin D is a prohormone and must undergo sequential hydroxylations by 1) vitamin D 25-hydroxylase to generate 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and 2) 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-alpha-hydroxylase 1 to generate the most polar and bioactive vitamin D metabolite, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D). Due to the short half-life of 1,25(OH)2D in plasma, the major circulating form of vitamin D, 25(OH)D, is currently considered the best indicator of vitamin D status in the body 2.

1, 25(OH)2D exerts its biological activity by binding to and activating the vitamin D receptor (VDR). The liganded VDR heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), or occasionally the retinoic acid receptor (RAR), to form the regulatory complex that has been shown to control the expression of as much as 3% of the transcribed genome in target cells 3.

Vitamin D insufficiency (circulating 25(OH)D levels of < 30 ng/dL) is endemic in the human population with more than a billion people affected worldwide1. Epidemiological data indicate that vitamin D deficiency (circulating 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/dL) is common in patients with cardiovascular disease1. Reduced plasma 25(OH)D levels are associated with increased risk of hypertension4, 5, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and early mortality 6. In selected interventional studies, investigators have shown that vitamin D treatment improves endothelial function7–9, lowers blood pressure 10, and reverses cardiac hypertrophy 11, 12 in humans. These clinical data support the notion that vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and that restoration of vitamin D levels may mitigate this risk.

Until recently, studies of 1, 25(OH)2D action were largely confined to the intestinal mucosa and bone where its calcitropic properties have been shown to be critical in supporting skeletal mineralization. More recently, it has become apparent that 1,25(OH)2D targets multiple organ systems, modulating functions ranging from epidermal development to immune response to cardiovascular function. VDR and the synthetic machinery for production of 1,25(OH)2D are present in multiple cell types throughout the heart and vasculature 13–15. We reported previously that the liganded VDR possesses anti-hypertrophic activity in the heart9, 13. The expression of the VDR in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts is up-regulated following exposure to hypertrophic stimuli in vitro and in hypertrophied hearts in vivo 13. In the vasculature, vitamin D has been shown to control vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cell proliferation15, 16. Several, though not all 17, animal studies suggest that vitamin D promotes blood vessel relaxation and reduces contractile responses to vasoconstrictors in animals with cardiovascular dysfunction 18, 19. The identity of the vascular cells targeted by vitamin D in these studies remains undefined. Endothelial dysfunction is seen in a variety of conditions that adversely impact the cardiovascular system, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia and chronic renal failure 20 – conditions which are also known to be associated with vitamin D deficiency. These associations suggested the possibility of a link between endothelial dysfunction and impaired signaling through the liganded VDR.

In an effort to address this issue in a directed fashion, we have generated a mouse with selective deletion of the VDR gene in endothelial cells. We show that these mice demonstrate impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and an augmented blood pressure response to the administration of angiotensin II (AngII). Collectively, the data suggest that VDR ligands exert an endothelium-dependent, palliative effect on the vascular tree that is likely to prove important in the maintenance of cardiovascular homeostasis.

Methods

A full description of Materials and Methods is available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Endothelial Cell-Specific VDR Knockout Mice

Generation and characterization of a mouse with a targeted (loxP-bordered) VDR gene allele has been reported previously 21. Endothelial cell-specific VDR gene knockout mice in the C57B6 mouse strain were generated by mating VDRloxp/loxp female mice with male mice expressing the Cre transgene under the control of Tie-2 gene promoter 22, which is selectively expressed in the endothelial cell. All experiments were carried out in mice at 12–24 weeks of age. All animal-related experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California San Francisco.

Results

The Presence of Vitamin D Receptor in Endothelial Cells

VDR gene expression has been demonstrated previously using immunohistochemical staining in venular and capillary endothelial cells of human skin biopsies14 and in endothelial cells lining the rat aorta23. We confirmed these findings in human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) using both Western Blot analysis and immunocytochemistry. In whole cell lysates of cultured HUVECs, Western analysis, using a rabbit antibody that recognizes the C terminus of VDR protein, detected a band migrating at 55kDa (Figure 1A), consistent with previously reported molecular weights for mammalian VDR proteins24. This band was eliminated when antibody was premixed with competing peptide (CP). The same antibody localized VDR protein to the HUVEC nuclei, as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Validation of expression of VDR in endothelial cells and generation of an endothelial cell-specific VDR knockout mouse. A. VDR expression in HUVECs. Parallel Western blots were incubated with antibody alone or antibody with a 5X competing peptide (CP). B. VDR protein was visualized by immunofluorescence (red, arrows) with anti-VDR in HUVECs. Nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI. Cell borders (green) were defined with anti-CD31. C. Schematic representation of the generation of endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse. D. Mouse with homozygous LoxP-bordered VDR allele was crossed with a Tie-2 Cre transgenic mouse to generate VDRECKO. Each mouse with Cre transgene showed a minor band corresponding to VDR gene deletion. VDR genotyping was performed by PCR using primers indicated with arrows (Figure 1C). E. VDR mRNA expression in endothelial cells and non-endothelial cells isolated from hearts of control and VDRECKO mice. ***p<0.001 (n=4). F. VDR protein expression in endothelial cells isolated from hearts of control and VDRECKO mice. L= loxp; VDR= vitamin D receptor; VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

Specific and Effective Deletion of VDR in VDRECKO Mouse

To explore the functional role of VDR in endothelial cells, we generated a mouse model with targeted deletion of VDR in endothelial cells using Cre-Lox technology. LoxP sites were placed in intron sequence surrounding exon 4 of the VDR gene with the intention of deleting the coding sequence of the second zinc finger of the VDR (Figure 1C). Successful elimination of VDR expression in the mouse cardiac myocyte using the same loxP-bordered allele has been reported previously 21. We used the Tie-2 promoter-driven Cre transgene 22 to promote VDR gene deletion in endothelial cells. Fig. 1D lanes 1 to 5 show genotyping of offspring resulting from mating a VDRloxp/loxp female mouse with a VDRloxp/loxp/Tie-2 Cre+ (VDRECKO) male mouse - a breeding strategy we used to generate all mice for the experiments presented below.

We isolated and cultured endothelial cells and non-endothelial cells (consisting of a mixture of cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells) from the hearts of control (VDRloxp/loxp) and VDRECKO mice. VDR mRNA levels in endothelial cells were reduced by 87% in VDRECKO whereas VDR expression levels in the non-endothelial cell population were unchanged (Figure 1E). Compared to the endothelial cells isolated from control mice, VDR protein expression in endothelial cells from VDRECKO mice was significantly reduced (Figure 1F). As predicted, deletion of VDR in endothelial cells did not affect plasma calcium or phosphorus levels (Figure S1) indicating that there was no perturbation of systemic mineral metabolism.

Impaired Vasodilation and Reduced eNOS Expression in Aorta from VDRECKO Mouse

Previous reports have linked vitamin D deficiency to impaired endothelial function 25. We investigated the role of endothelial VDR in supporting endothelial function by examining endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in an ex vivo model. We compared the vasorelaxant response to acetylcholine (ACh) in isolated aortae taken from control vs. VDRECKO mice. Figure 2A shows the real-time tracing of aortic tension from control vs. VDRECKO mice. Aortae from both groups were challenged with phenylepherine (PE) to generate half maximal, PE-induced contraction. Increased concentrations of ACh were then added to the tissue bath to induce endothelium-dependent relaxation. VDRECKO mouse aortae demonstrated impaired vasorelaxation compared to control aortae (Figure 2B). The relaxation to a maximal concentration of sodium nitroprusside (SNP, nitric oxide donor, 10−5 M), an endothelium-independent vasodilator, was not affected by VDR deletion in endothelial cells (Figure 2A). Similarly, there was no difference in the aortic contraction to PE in VDRECKO vs. control mice (Figure 2C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that endothelial cell-specific deletion of the VDR gene interferes selectively with endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in mouse aorta.

Figure 2.

Impaired blood vessel relaxation in aorta from VDRECKO mice. A. Representative tracings of ACh-induced, concentration-dependent aortic relaxation. Nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) relaxed aorta to baseline. B. Aortae from VDRECKO mice exhibit impaired acetylcholine-induced relaxation. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitor LNNA completely abolished ACh-induced aortic relaxation in aorta from control and VDRECKO mice. VDRL/L + LNNA (n=3); VDRECKO + LNNA (n=3); VDRL/L (n=5); VDRECKO (n=5). C. Comparable contractile response to PE in aorta from control and VDRECKO mice. *p<0.05 (n=5 for each group). VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

ACh-induced relaxations were completely blocked by the eNOS inhibitor (NG-nitro-L-Arginine or LNNA) in both groups (Figure 2B) confirming the fact that nitric oxide is the principal mediator of ACh-induced relaxation in mouse aorta26. By inference, this suggests that the different vasorelaxant responses that we observed between control and VDRECKO mice could reflect differences in eNOS expression and/or activity. As shown in Fig. 3A, we found that eNOS mRNA levels were reduced to 62% of those found in control aortae. We found a similar reduction in eNOS protein levels (~37%) in aortae from VDRECKO vs. control mice (Figure 3B). The levels of phospho-VASP (vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein), a cyclic GMP-sensitive marker of nitric oxide activity 27(Figure 3C), were also reduced. These results support the notion that VDR deletion in endothelial cells results in impaired nitric oxide signaling. Endothelin-1, a peptide produced predominantly in endothelial cells, is a powerful vasoconstrictor and mitogen which stimulates fibrogenesis 28. A vitamin D analog has been shown to repress high matrix stiffness-induced ET-1 gene transcription29. However, we found no change in pre-proendothelin-1 mRNA expression in aortae from VDRECKO vs. control mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Reduced eNOS expression in aorta from VDRECKO mice. A. eNOS mRNA expression in aorta from control and VDRECKO mice (n=4). B. eNOS protein expression in aorta from control and VDRECKO mice (n=6). VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse. C. Representative Western blot (left) and quantification (right) of basal p-VASP level detected by Western blot in aorta from control and VDRECKO mice (n=4). VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO = endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

Since reactive oxygen species like superoxide have been shown to impair endothelial function in a number of systems 30–32 we assessed superoxide levels by dihydroethidium (DHE) staining on frozen cross-sections of aortae from control and VDRECKO mice at 12 weeks of age. We found a significantly higher level of superoxide in the endothelium from VDRECKO mice compared to that in the control mice and this difference extended to the entire vascular wall (Figure S2).

It is important to note that Tie-2 Cre expression has also been reported in myeloid cells33. As macrophages from the myeloid lineage are known to contain VDR and might contribute to the phenotypes we are seeing, we sought to determine if macrophage number was altered in the VDRECKO aortae at baseline. To address this we analyzed aortic cell suspensions for the presence of CD11b+ and F4:80+ cells (CD11b is a marker for the myeloid linage and F4:80 for macrophage) by FACS analysis. Isolated aortic cells were stained with CD45 antibody to identify leukocytes in the preparation. There was no significant difference in CD45+ cell number in the control vs. VDRECKO samples (Figure S3). Macrophage number, normalized for live cells (Figure S3) or the number of CD45+ cells did not differ significantly in VDR L/L vs VDRECKO aortic suspensions. If anything there appeared to be a slight, albeit nonsignificant, trend towards a smaller percentage of macrophages in the VDRECKO aortae. Macrophage number was consistent with what has previously been reported in aortic cell suspensions34. Our data suggest that the impaired vasorelaxant activity seen in VDRECKO mice results from VDR deletion in endothelial cells.

Blood Pressure and Cardiac Response to AngII Infusion is Increased in Mice Deficient in Endothelial VDR

At 24 weeks of age, VDRECKO mice had similar blood pressure and heart weight/body weight ratio compared to control mice (Figure S4). Cross-sectional H&E staining of aorta and carotid artery showed normal blood vessel morphology in the VDRECKO mouse (Figure S4). Collectively, these data suggest that, at baseline, the cardiovascular phenotype of the VDRECKO mice is not appreciably different from the controls.

To evaluate the phenotype of the VDRECKO mouse under the challenge of cardiovascular stress, we subjected 12 to 14 week old VDRECKO and control mice to 2 weeks of AngII-infusion. We used a low dose of AngII (500 ng/kg/min) to induce a mild increase in blood pressure with minimal cardiac hypertrophy. Blood pressures were measured using the tail cuff method 21 before, 1 week and 2 weeks following initiation of vehicle or AngII infusion. Blood pressures, prior to osmotic mini pump implantation, were comparable at 12–14 weeks of age in control vs. VDRECKO mice. After one week, mice receiving AngII had minimal-to-moderate increases in blood pressure, as expected (Figure 4). However, the level of blood pressure induction was significantly higher in VDRECKO mice vs. controls (155.8±14.9 mmHg vs. 132.9±7.8 mmHg). Blood pressure levels continued to rise by the end of two weeks of AngII-infusion and the difference between VDRECKO and control mice (Figure 4A, B and C) was maintained.

Figure 4.

Tail cuff measurements of SBP (A), DBP (B) and MAP (C) in control and VDRECKO mice before, 1 week or 2 weeks after saline or AngII infusion. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. VDRL/L + saline (n=6); VDRL/L + Ang II (n=6); VDRECKO + saline (n=6); VDRECKO +Ang II (n=5). VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

AngII infusion caused thickening of the aortic wall (fold change compared to saline-infused VDRL/L control mice, AngII-infused VDRL/L mice= 1.38±0.02, p<0.05; saline-infused VDRECKO= 1.03±0.01; AngII-infused VDRECKO=1.25±0.1, p<0.05), as demonstrated by H&E staining. In addition, AngII treatment resulted in increased vascular fibrosis, as demonstrated by Masson’s trichrome staining of aortic cross sections (Figure 5). However, there were no differences between AngII treated VDRL/L controls and VDRECKO mice in either vessel wall thickness or fibrosis.

Figure 5.

Similar changes in blood vessel morphology in aortae with AngII infusion. A. H&E staining of aortae from control and VDRECKO mice following treatment with saline or AngII infusion. B. Masson’s Trichrome staining of aortae from control and VDRECKO mice following treatment with saline or AngII infusion. VDRL/L + saline (n=4); VDRL/L + Ang II (n=4); VDRECKO + saline (n=5); VDRECKO +Ang II (n=5). VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

The effects of AngII on the heart were evaluated after the two weeks of infusion. Figure 6A shows H&E staining of cardiac sections from the four groups of animals. Gravimetric analysis showed similar increases in heart weight/body weight ratio in control and VDRECKO mice with AngII infusion (Figure 6B). The size of cardiac myocytes was evaluated using a computerized automated program (http://www.le.ac.uk/biochem/microscopy/macros.html). Similar to the results obtained for the heart weight/body weight ratio, increases in myocyte size were comparable in control vs. VDRECKO mice following AngII-infusion (Figure 6C and 6D). However, when we measured more sensitive markers of cardiac hypertrophy (i.e., the expression of fetal genes in left ventricular myocardium), we found that AngII-induced type-A natriuretic peptide (ANP) and type-B natriuretic peptide (BNP) gene expression were increased to a higher level in hearts from VDRECKO mice compared to controls (Figure 6E and 6F).

Figure 6.

AngII infusion-induced cardiac hypertrophy in control and VDRECKO mice. A. H&E staining of hearts. B. Left ventricle weight over body weight ratio VDRL/L + saline (n=6); VDRL/L + Ang II (n=6); VDRECKO + saline (n=6); VDRECKO +Ang II (n=5). C. WGA staining of hearts. D. Quantification of cardiac myocyte size VDRL/L + saline (n=7); all other groups n=6. E. Expression of hypertrophic marker gene encoding ANP. VDRECKO +Ang II (n=6); all other groups =7. F. BNP gene expression. VDRL/L + saline (n=8); VDRL/L + Ang II (n=8); VDRECKO + saline (n=7); VDRECKO +Ang II (n=7). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

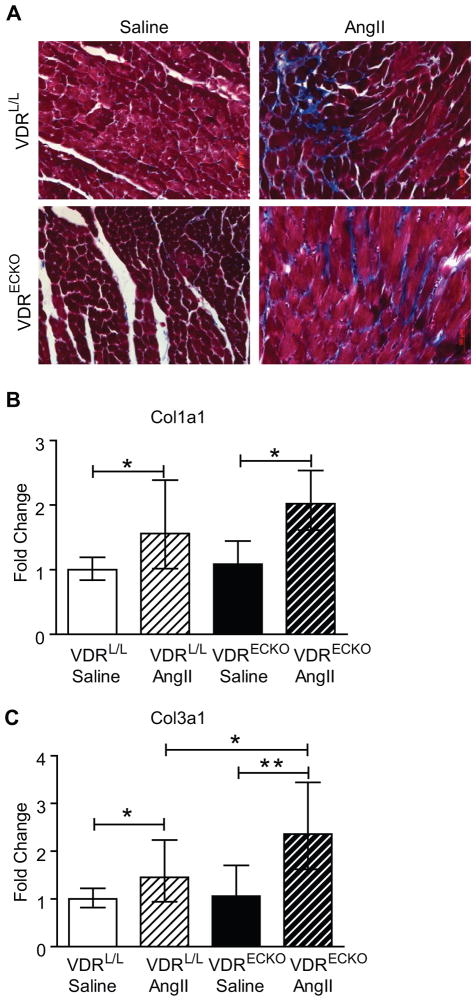

AngII infusion-induced a mild degree of cardiac fibrosis in both control and VDRECKO mice as demonstrated by Masson’s trichrome staining of cardiac sections (Figure 7A). Gene expression analysis showed that collagen 1a1 and collagen 3a1 mRNA increased with AngII-infusion, as expected 35 (Figure 7B). Additionally, as noted with the hypertrophic marker genes above, collagen 3a1 was induced to a greater extent in hearts from VDRECKO mice.

Figure 7.

AngII infusion-induced cardiac fibrosis in control and VDRECKO mice. A. Masson’s trichrome staining of hearts. B. Col 1a1 and Col 3a1 expression in hearts from control and VDRECKO mice after receiving saline or AngII-infusion for two weeks. VDRL/L + saline (n=6); VDRL/L + Ang II (n=6); VDRECKO + saline (n=6); VDRECKO +Ang II (n=5). *p<0.05; **p<0.01. VDRL/L= VDR floxed mouse, served as control; VDRECKO= endothelial cell specific VDR gene knockout mouse.

Discussion

The present study provides the first evidence of a direct protective role for the endothelial VDR in regulating vascular tone. Our results show that the deletion of VDR in endothelial cells leads to endothelial dysfunction (demonstrated by impaired blood vessel relaxation) and sensitization of mice to the hypertensive effects of AngII infusion. Given the acknowledged importance of endothelial function to cardiovascular homeostasis, the protective activity of VDR in vascular endothelium may account for at least some of the reported beneficial effects attributed to vitamin D in preventing or reversing cardiovascular disease 36, 37.

A number of epidemiological studies have demonstrated that individuals with low plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D, the best measure of vitamin D status in humans, are at higher risk for all cause as well as cardiovascular mortality 38, 39, myocardial infarction 40 and hypertension 4, 5. However, these relationships remain controversial 41 and interventional studies have, by and large, failed to demonstrate major effects of vitamin D on reversing cardiovascular disease outcomes 42, suggesting that this is an area worthy of further investigation.

One potential target for vitamin D in the cardiovascular system is the endothelial cell. Endothelial cells have been shown to express VDR as well as the ligand-generating 1-alpha- hydroxylase14, implying that they possess the capacity for orchestrating local vitamin D-dependent regulatory activity that is confined to the vascular wall. Experimental animal studies support a role for vitamin D in regulating endothelial function. Expression of eNOS was shown to be reduced by 50% in aortic tissue taken from VDR gene knockout (VDR−/−, global VDR knockout) versus wild type mice43. Noteworthy, the authors in that study attributed this reduction to hypocalcemia in the VDR−/− mouse. In our study VDRECKO mice were normocalcemic (Figure S1). In another study, advanced glycation end products reduced eNOS gene expression and enzymatic activity. These were restored following treatment with 1,25(OH)2D 44. VDR activators (e.g., paricalcitol) have also been shown to mitigate endothelial dysfunction in animals with renal insufficiency. In rats with 5/6 nephrectomy, VDR gene expression was found to be reduced in the endothelium but not in the smooth muscle layer of the vascular wall. This endothelial specific VDR deficiency was restored after vitamin D analogue treatment 45. Two weeks of paricalcitol treatment dose-dependently improved ACh-induced (endothelium-dependent) relaxation in blood vessels from 5/6 nephrectomized rats 25. In addition, the improved relaxation was abolished by a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor suggesting that paricalcitol affected endothelial function by increasing nitric oxide production 25, a finding which complements those reported here.

A number of clinical studies have demonstrated an inverse correlation between plasma 25(OH)D levels and endothelial function, assessed by flow mediated vasodilation, in humans. Tarcin and colleagues showed that 25(OH)D deficiency was associated with endothelial dysfunction, and vitamin D replacement was found to be effective in reversing this dysfunction 46. Jablonski and coworkers found that endothelium-dependent brachial artery flow-mediated dilation was lower in vitamin D insufficient and vitamin D deficient vs. vitamin D sufficient individuals while endothelium-independent brachial artery dilation did not differ between the groups47. Of note, they found an increase in inflammation-linked markers in vitamin D deficient vs. sufficient subjects and a reduction in both VDR and 1-α hydroxylase expression. They speculated that reduced VDR and local 1,25(OH)2D synthesis might account for the link between vitamin D insufficiency and endothelial dysfunction. Harris et al showed that 16 weeks of vitamin D supplementation (60,000 IU monthly) led to significant improvement in flow-mediated dilation in overweight African-American adults 8. In view of the well established link between endothelial dysfunction and adverse cardiovascular events 20, one could speculate that the increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality noted above 1 is, at least in part, a reflection of the impaired endothelial function that accompanies inadequate vitamin D activity.

Natriuretic peptides, especially BNP, have been considered as diagnostic markers for asymptomatic and symptomatic cardiac dysfunction as well as prognostic markers in patients with heart failure48, 49. A recent study showed that even modest elevations in BNP in asymptomatic hypertensive patients can be linked to sub-clinical cardiac remodeling, inflammation and extracellular matrix changes50. Increases in both ANP and BNP gene expression were amplified in the hearts from VDRECKO mice after Ang II infusion, implying a reduction in the threshold for development of Ang II-dependent cardiac pathology. What remains unclear is whether this phenotype (ie, increased expression of natriuretic peptide genes) is a direct result of dysfunctional cardiac endothelial cells, which support cardiac myocyte and fibroblast function 51, 52, or whether this is an indirect phenomenon resulting from the modestly elevated blood pressures seen in VDRECKO mice.

The casual role of superoxide in contributing to endothelial dysfunction has been studied for more than a decade 30–32. Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to increased oxidative stress in previous studies 53, while vitamin D supplementation has been shown to reverse this process in a variety of tissues, including the vasculature 4, 5, 54, 55. The antioxidant effect of vitamin D was shown to be mediated by the MEK/ERK/SirT-1 axis in endothelial cells56. Chronic treatment of the spontaneously hypertensive rat with calcitriol normalized elevations in ROS and expression of AT(1)R and NAD(P)H oxidase subunits in the vasculature 56. More recently, calcitriol treatment of renal arteries from hypertensive patients, in vitro, has been shown to improve endothelial function and reduce oxidative stress by reducing AT(1)R and NAD(P)H oxidase subunits and increasing SOD-1, and SOD-2 expression 55. Our data are consistent with these previous findings and demonstrate the important role of VDR in supporting endothelial function more directly in an in vivo model.

As noted above, Tie2-Cre has been shown to be expressed in cells of the myeloid lineage (e.g., macrophage) raising the possibility that deletion of the VDR in these cells could contribute to the phenotype observed here. We have examined both aortic sections (immunocytochemistry) and dispersed aortic cells (FACS) for the presence of immune cells, including cells of the myeloid lineage, and found no difference between the VDRECKO and control mice. This suggests that the observed effects on vasorelaxant activity and NOS gene expression and activity result from deletion of the VDR gene in the endothelial cell. While it would appear likely that this would have an effect on blood pressure as well, given the complexity of blood pressure regulation in vivo and the known pro-inflammatory effects of angiotensin II in the cardiovascular system 57 it remains possible that some portion of the effects of Tie2-Cre generated VDR deletion could result from coincident reduction of liganded VDR activity in myeloid cells.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

The fact that VDR is expressed in many, if not most, cells of the cardiovascular system 13–15 makes it difficult to dissect out the mechanism(s) of vitamin D’s cardiovascular effects using subjects with vitamin D deficiency or whole animal VDR deletion, since many confounding factors (i.e., changes in PTH levels or calcium homeostasis) could potentially contribute to the phenotype. Using a mouse model with selective elimination of VDR in endothelial cells, we have provided direct evidence that vitamin D regulates endothelium-dependent blood vessel relaxation and arterial blood pressure, possibly by modulating eNOS gene expression. Our data add another piece of evidence supporting the hypothesis that vitamin D exerts palliative effects in the cardiovascular system and imply that vitamin D or its less-calcemic analogues may be useful in the prevention and/or treatment of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases that are associated with endothelial dysfunction.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New

We showed a direct protective role of the endothelial VDR in regulating vascular tone in vivo. Blood pressure and reactive oxygen species generation were higher in the VDRECKO mouse vs. controls.

What Is Relevant

Endothelial dysfunction contributes to the development of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Vitamin D action in endothelial cells plays a role in protecting cardiovascular homeostasis, supporting the notion of using vitamin D agonists in preventing and treating cardiovascular diseases.

Summary

These findings indicate that vitamin D receptor is an important regulator of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Our data provides additional support for the hypothesis that vitamin D exerts palliative effects in the cardiovascular system and implies that vitamin D or its less-calcemic analogues may be useful in the prevention and/or treatment of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases that are associated with endothelial dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kees Straatman at University of Leicester for his assistance on myocyte size quantification.

Sources of Funding

American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship to WN

K08 NIH HL086158 to DJG

HL45637 from National Institutes of Health to DGG

Grants from the Center for D-receptor Activation Research (CeDAR) Foundation and the UCSF

Diabetes Center Family Fund to DGG

Footnotes

Disclosure

None

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin d deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wootton AM. Improving the measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin d. Clin Biochem Rev. 2005;26:33–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haussler MR, Haussler CA, Bartik L, Whitfield GK, Hsieh J-C, Slater S, Jurutka PW. Vitamin d receptor: Molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutrition Reviews. 2008;66:S98–S112. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Tworoger SS, Willett WC, Curhan GC. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman JP, Curhan GC, Taylor EN. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and risk of incident hypertension among young women. Hypertension. 2008;52:828–832. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.117630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brondum-Jacobsen P, Benn M, Jensen GB, Nordestgaard BG. 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and risk of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and early death: Population-based study and meta-analyses of 18 and 17 studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2794–2802. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ertek S, Akgul E, Cicero AF, Kutuk U, Demirtas S, Cehreli S, Erdogan G. 25-hydroxy vitamin d levels and endothelial vasodilator function in normotensive women. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:47–52. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.27280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris RA, Pedersen-White J, Guo DH, Stallmann-Jorgensen IS, Keeton D, Huang Y, Shah Y, Zhu H, Dong Y. Vitamin d3 supplementation for 16 weeks improves flow-mediated dilation in overweight african-american adults. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:557–562. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugden JA, Davies JI, Witham MD, Morris AD, Struthers AD. Vitamin d improves endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and low vitamin d levels. Diabet Med. 2008;25:320–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, Nachtigall D, Hansen C. Effects of a short-term vitamin d(3) and calcium supplementation on blood pressure and parathyroid hormone levels in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1633–1637. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HW, Park CW, Shin YS, Kim YS, Shin SJ, Kim YS, Choi EJ, Chang YS, Bang BK. Calcitriol regresses cardiac hypertrophy and qt dispersion in secondary hyperparathyroidism on hemodialysis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;102:c21–29. doi: 10.1159/000088295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CW, Oh YS, Shin YS, Kim CM, Kim YS, Kim SY, Choi EJ, Chang YS, Bang BK. Intravenous calcitriol regresses myocardial hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S, Glenn DJ, Ni W, Grigsby CL, Olsen K, Nishimoto M, Law CS, Gardner DG. Expression of the vitamin d receptor is increased in the hypertrophic heart. Hypertension. 2008;52:1106–1112. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.119602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merke J, Milde P, Lewicka S, Hugel U, Klaus G, Mangelsdorf DJ, Haussler MR, Rauterberg EW, Ritz E. Identification and regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 receptor activity and biosynthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3. Studies in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and human dermal capillaries. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1903–1915. doi: 10.1172/JCI114097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitsuhashi T, Morris RC, Jr, Ives HE. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 modulates growth of vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1889–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI115213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantell DJ, Owens PE, Bundred NJ, Mawer EB, Canfield AE. 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin d(3) inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res. 2000;87:214–220. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bukoski RD, Wang DB, Wagman DW. Injection of 1,25-(oh)2 vitamin d3 enhances resistance artery contractile properties. Hypertension. 1990;16:523–531. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borges AC, Feres T, Vianna LM, Paiva TB. Recovery of impaired k+ channels in mesenteric arteries from spontaneously hypertensive rats by prolonged treatment with cholecalciferol. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:772–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borges AC, Feres T, Vianna LM, Paiva TB. Effect of cholecalciferol treatment on the relaxant responses of spontaneously hypertensive rat arteries to acetylcholine. Hypertension. 1999;34:897–901. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadi HA, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: Cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1:183–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S, Law CS, Grigsby CL, Olsen K, Hong TT, Zhang Y, Yeghiazarians Y, Gardner DG. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the vitamin d receptor gene results in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2011;124:1838–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braren R, Hu H, Kim YH, Beggs HE, Reichardt LF, Wang R. Endothelial fak is essential for vascular network stability, cell survival, and lamellipodial formation. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:151–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong MS, Delansorne R, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Vitamin d derivatives acutely reduce endothelium-dependent contractions in the aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H289–296. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00116.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones G, Strugnell SA, DeLuca HF. Current understanding of the molecular actions of vitamin d. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1193–1231. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu-Wong JR, Noonan W, Nakane M, Brooks KA, Segreti JA, Polakowski JS, Cox B. Vitamin d receptor activation mitigates the impact of uremia on endothelial function in the 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:625852. doi: 10.1155/2010/625852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tykocki NR, Gariepy CE, Watts SW. Endothelin et(b) receptors in arteries and veins: Multiple actions in the vein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:875–881. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Daum G, Chitaley K, Coats SA, Bowen-Pope DF, Eigenthaler M, Thumati NR, Walter U, Clowes AW. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein regulates proliferation and growth inhibition by nitric oxide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1403–1408. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134705.39654.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalil RA. Modulators of the vascular endothelin receptor in blood pressure regulation and hypertension. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011;4:176–186. doi: 10.2174/1874467211104030176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson LA, Sauder KL, Rodansky ES, Simpson RU, Higgins PD. Card-024, a vitamin d analog, attenuates the pro-fibrotic response to substrate stiffness in colonic myofibroblasts. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikalov SI, Nazarewicz RR, Bikineyeva A, Hilenski L, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Dikalova AE. Nox2-induced production of mitochondrial superoxide in angiotensin ii-mediated endothelial oxidative stress and hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:281–294. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pernomian L, Santos Gomes M, Baraldi Araujo Restini C, Naira Zambelli Ramalho L, Renato Tirapelli C, Maria de Oliveira A. The role of reactive oxygen species in the modulation of the contraction induced by angiotensin ii in carotid artery from diabetic rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;678:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigo R, Gonzalez J, Paoletto F. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:431–440. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Constien R, Forde A, Liliensiek B, Grone HJ, Nawroth P, Hammerling G, Arnold B. Characterization of a novel egfp reporter mouse to monitor cre recombination as demonstrated by a tie2 cre mouse line. Genesis. 2001;30:36–44. doi: 10.1002/gene.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tieu BC, Lee C, Sun H, Lejeune W, Recinos A, 3rd, Ju X, Spratt H, Guo DC, Milewicz D, Tilton RG, Brasier AR. An adventitial il-6/mcp1 amplification loop accelerates macrophage-mediated vascular inflammation leading to aortic dissection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3637–3651. doi: 10.1172/JCI38308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichihara S, Senbonmatsu T, Price E, Jr, Ichiki T, Gaffney FA, Inagami T. Angiotensin ii type 2 receptor is essential for left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in chronic angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Circulation. 2001;104:346–351. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin d supplementation and total mortality: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic review: Vitamin d and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152:315–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semba RD, Houston DK, Bandinelli S, Sun K, Cherubini A, Cappola AR, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Relationship of 25-hydroxyvitamin d with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in older community-dwelling adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:203–209. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, Ritz E, Pieber TR. Vitamin d status and arterial hypertension: A systematic review. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:621–630. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25-hydroxyvitamin d and risk of myocardial infarction in men: A prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elamin MB, Abu Elnour NO, Elamin KB, Fatourechi MM, Alkatib AA, Almandoz JP, Liu H, Lane MA, Mullan RJ, Hazem A, Erwin PJ, Hensrud DD, Murad MH, Montori VM. Vitamin d and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1931–1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pittas AG, Chung M, Trikalinos T, Mitri J, Brendel M, Patel K, Lichtenstein AH, Lau J, Balk EM. Systematic review: Vitamin d and cardiometabolic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:307–314. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aihara K, Azuma H, Akaike M, Ikeda Y, Yamashita M, Sudo T, Hayashi H, Yamada Y, Endoh F, Fujimura M, Yoshida T, Yamaguchi H, Hashizume S, Kato M, Yoshimura K, Yamamoto Y, Kato S, Matsumoto T. Disruption of nuclear vitamin d receptor gene causes enhanced thrombogenicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35798–35802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talmor Y, Golan E, Benchetrit S, Bernheim J, Klein O, Green J, Rashid G. Calcitriol blunts the deleterious impact of advanced glycation end products on endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1059–1064. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00051.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E, Schmitt CP, Gross ML. A calcimimetic (r-568), but not calcitriol, prevents vascular remodeling in uremia. Kidney Int. 2009;75:60–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarcin O, Yavuz DG, Ozben B, Telli A, Ogunc AV, Yuksel M, Toprak A, Yazici D, Sancak S, Deyneli O, Akalin S. Effect of vitamin d deficiency and replacement on endothelial function in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4023–4030. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jablonski KL, Chonchol M, Pierce GL, Walker AE, Seals DR. 25-hydroxyvitamin d deficiency is associated with inflammation-linked vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension. 2011;57:63–69. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anand IS, Fisher LD, Chiang YT, Latini R, Masson S, Maggioni AP, Glazer RD, Tognoni G, Cohn JN, Val-He FTI. Changes in brain natriuretic peptide and norepinephrine over time and mortality and morbidity in the valsartan heart failure trial (val-heft) Circulation. 2003;107:1278–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000054164.99881.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Couto G, Ouzounian M, Liu PP. Early detection of myocardial dysfunction and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:334–344. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phelan D, Watson C, Martos R, Collier P, Patle A, Donnelly S, Ledwidge M, Baugh J, McDonald K. Modest elevation in bnp in asymptomatic hypertensive patients reflects sub-clinical cardiac remodeling, inflammation and extracellular matrix changes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tirziu D, Simons M. Endothelium-driven myocardial growth or nitric oxide at the crossroads. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoenig MR, Bianchi C, Rosenzweig A, Sellke FW. The cardiac microvasculature in hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic heart failure. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2008;6:292–300. doi: 10.2174/157016108785909779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Argacha JF, Egrise D, Pochet S, Fontaine D, Lefort A, Libert F, Goldman S, van de Borne P, Berkenboom G, Moreno-Reyes R. Vitamin d deficiency-induced hypertension is associated with vascular oxidative stress and altered heart gene expression. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:65–71. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821c832f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haussler MR, Haussler CA, Bartik L, Whitfield GK, Hsieh JC, Slater S, Jurutka PW. Vitamin d receptor: Molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:S98–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dong J, Wong SL, Lau CW, Lee HK, Ng CF, Zhang L, Yao X, Chen ZY, Vanhoutte PM, Huang Y. Calcitriol protects renovascular function in hypertension by down-regulating angiotensin ii type 1 receptors and reducing oxidative stress. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2980–2990. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polidoro L, Properzi G, Marampon F, Gravina GL, Festuccia C, Di Cesare E, Scarsella L, Ciccarelli C, Zani BM, Ferri C. Vitamin d protects human endothelial cells from h(2)o(2) oxidant injury through the mek/erk-sirt1 axis activation. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:221–231. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruiz-Ortega M, Esteban V, Ruperez M, Sanchez-Lopez E, Rodriguez-Vita J, Carvajal G, Egido J. Renal and vascular hypertension-induced inflammation: Role of angiotensin ii. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:159–166. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000203190.34643.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.