SYNOPSIS

Objective

The current study investigated the role of infant temperament in stability and change in coparenting behavior across the infant’s first year. Specifically, bidirectional relations between infant temperament and coparenting were examined and temperament was further considered as a moderator of longitudinal stability in coparenting behavior.

Design

Fifty-six two-parent families were recruited to participate during their third trimester of pregnancy. Coparenting behavior was assessed in families' homes when infants were age 3.5 months and in a laboratory setting at 13 months postpartum. Mothers and fathers also reported on their infant's temperamental difficulty at 3.5 and 13 months.

Results

Evidence for bidirectional relations between infant temperament and coparenting was obtained. Early infant difficulty, as reported by fathers, was associated with a decrease in supportive coparenting behavior across time; conversely, early supportive coparenting behavior was associated with a decrease in infant difficulty. Moreover, infant difficult temperament moderated stability in undermining coparenting behavior, such that undermining behavior at 3.5 months predicted undermining behavior at 13 months only when infants had less difficult temperaments.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that infants may play a role in the early course of the family processes that shape their development. With respect to practice, these results suggest that early intervention in the coparenting subsystem is essential for families, particularly those with temperamentally difficult infants.

Family systems theory posits that families are larger systems composed of smaller subsystems (Minuchin, 1974). One of these subsystems is the coparenting relationship, which is the relationship parents share as “co-managers of family members’ behaviors and relationships” (Feinberg, 2003, p. 96). Although the coparenting subsystem includes the same members as the marital subsystem, the coparenting subsystem includes only the aspects of the marital relationship that are relevant for parenting (Feinberg, 2003). These two subsystems are separated by boundaries in normally functioning families (Minuchin, 1974), and empirical research has supported this claim, as these subsystems seem to act in related but separate ways within the family (Bonds & Gondoli, 2007; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Frosch, & McHale, 2004). The functioning of the coparenting relationship can be chiefly described by the extent to which parents support or undermine each other's parenting efforts (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996; McHale, 1995).

Research on coparenting has experienced significant growth in recent years, due in part to empirical demonstrations that coparenting relationship quality appears to influence child outcomes above and beyond the impact of other family relationships (McHale, 2007; McHale et al., 2002). For example, in a study by Frosch, Mangelsdorf, and McHale (2000), it was hostile couple (coparental) behavior during triadic play in infancy that forecasted less secure child-mother attachment relationships, not marital conflict assessed in a dyadic setting. Similarly, McHale and Rasmussen (1998) found that coparenting relationship quality in infancy predicted child aggression at age three over and above marital relationship quality and maternal well-being. In the first study to include assessments of both coparenting and parent-child relationships, Belsky et al. (1996) found that although parenting and coparenting behaviors both predicted toddlers’ behavioral inhibition, coparenting explained additional portions of the variance in toddler inhibition above and beyond parenting. Corroborating Belsky et al.'s findings, McHale, Johnson, and Sinclair (1999) demonstrated that coparenting accounted for a significant portion of the variance in children’s family representations (which were associated with children’s peer competence), over and above parenting.

Given the unique effects of coparenting on children’s development, attention has turned to understanding the development of coparenting behavior itself. Researchers concur that the coparenting relationship forms across the transition to parenthood and is influenced by multiple factors (Doherty & Beaton, 2004; Feinberg, 2003; McHale et al., 2004; Van Egeren, 2003). Once coparenting is established, the quality of the relationship tends to persist across the first year of life (Fivaz-Depeursinge, Frascarolo, & Corboz-Warnery, 1996; McHale & Rotman, 2007; Van Egeren, 2004). Although a coparenting relationship comes into being by virtue of the presence of an infant, little research has explored how children’s characteristics and behavior may influence the early course of the coparenting relationship. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine the role of infant temperament in stability and change in coparenting behavior across the infant’s first year. Knowing how infants may influence the coparenting relationship is important for developmental researchers; if infant behavior affects coparenting and coparenting affects infant behavior, then infants are at least in part driving their own development.

Infant Temperament and Coparenting

The idea that infants influence their parents is not new to the theoretical literature. Seminal work by Bell (1968) suggests that from birth, infants engage in behaviors designed to evoke a response from their parents. These ideas led to transactional models of development, which, stated simply, suggest that just as parents influence infants, so too do infants influence parents (Sameroff, 1975). Moreover, family systems theory posits that change in one part of a system affects change in all other parts of the system (Minuchin, 1974), and certainly the addition of a new family member who brings with him/her particular temperamental characteristics is one such important change. As such, family relationships may develop along different paths depending in part on a new infant's nascent personality.

Although theorists have long considered infants’ influence on the family system, empirical tests of these ideas have largely focused on relations between infant temperament and early mother-child dyadic relationships. Research on the role of infant temperament in other family relationships is scant (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003). Those few studies that have examined direct relations between infant temperament and coparenting have yielded mixed results. Consistent with several studies linking more difficult infant temperament with poorer marital relationship quality across the transition to parenthood (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003), Van Egeren (2004) reported that fathers perceived coparenting less positively when they perceived their infants as more difficult. Similarly, Lindsey, Caldera, and Colwell (2005) found that fathers of difficult infants demonstrated more intrusive coparenting. Conflicting results came from Berkman, Alberts, Carleton and McHale (2002), who found that infants rated as more negative and inhibited by observers had parents who actually showed greater coparental cooperation during triadic play. In two recent papers, however, McHale et al. (2004) and Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Brown, and Sokolowski (2007) reported few direct associations between infant temperament and coparenting during the early postpartum period.

However, the studies that obtained no clear evidence for direct relations between infant temperament and coparenting (McHale et al., 2004; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007) only included data on these variables at one time point during the early postpartum period (i.e., 3–4 months postpartum). It is possible that more time is needed for the effects of infant temperament on coparenting to become apparent. Thus, one goal of the current study was to further examine direct relations between difficult infant temperament and coparenting behavior, and to examine these relations across the infant’s first year.

In contrast to the equivocal evidence for direct effects of infant temperament on coparenting, the evidence for a more indirect role of infant temperament is stronger. In particular, and consistent with Crockenberg and Leerkes' (2003) transactive model of infant negative emotionality and family relationships, several studies indicate that infant temperament may affect coparenting when combined with other factors. Research by McHale and colleagues (2004) demonstrated that high levels of prebirth maternal pessimism about the future family only predicted lower postbirth coparenting quality if the infant was high in negative reactivity. Corroborating these patterns, Schoppe-Sullivan et al. (2007) found that couples with more temperamentally challenging (fussy, unadaptable) infants only showed less adaptive coparenting behavior when they also had the disadvantage of having a poorer marital relationship prior to their infant's birth. In contrast, couples with strong prebirth marital relationships actually demonstrated especially high-quality coparenting when faced with a challenging infant.

As noted above, these studies considered the role of infant temperament with respect to the initial character of the coparenting relationship during the early postpartum period. Once coparenting behavior patterns are established, an equally important question is whether infant temperament affects the endurance of those patterns. Given past research (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996; McHale & Rotman, 2007; Van Egeren, 2004), there is reason to expect modest to moderate stability in coparenting during infancy. However, consistency in coparenting may be a reality for some families but not for others. In this study we extended prior research by examining whether temperament moderated stability in coparenting across the infant's first year.

The Current Study

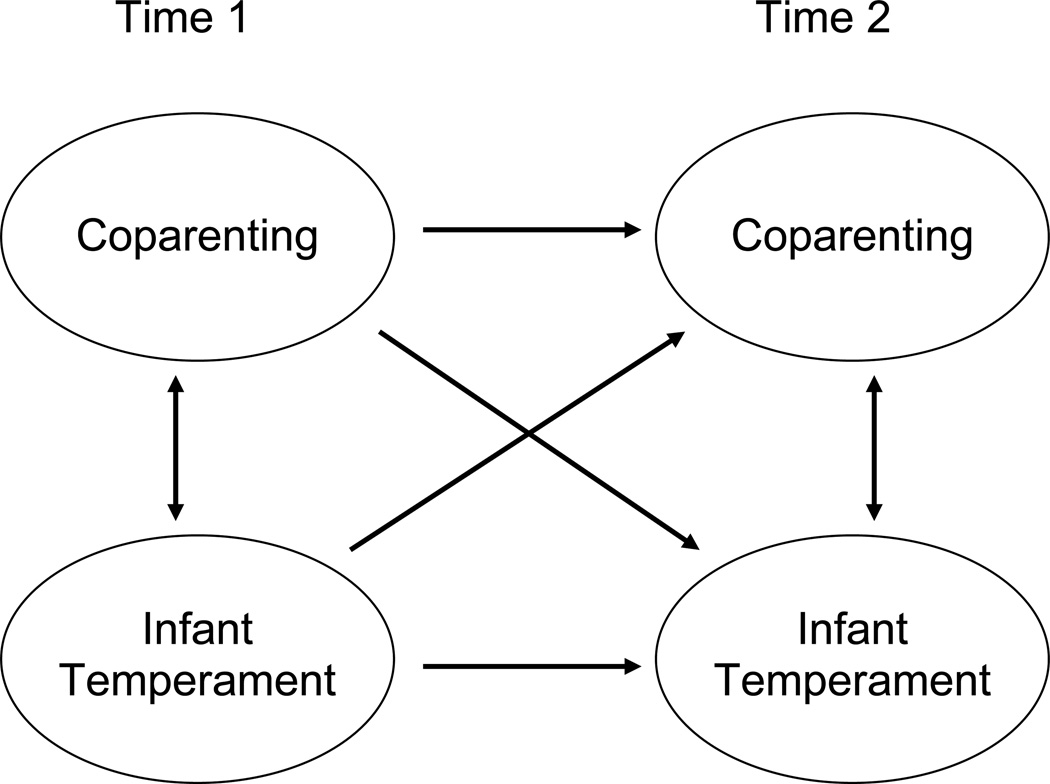

In sum, the current study addressed two questions: (1) What are the relations between infant temperament and coparenting behavior across the first year of life? (2) Does infant temperament moderate stability in coparenting across the infant's first year? Data used in this study were drawn from a longitudinal study of families that included observational assessments of coparenting at infant age 3.5 and 13 months, as well as mothers' and fathers’ perceptions of their infant's temperamental difficulty at both time points. By including measures of both coparenting behavior and infant temperament during the early post-transition period and at the end of the infant’s first year, we were able to examine the reciprocal relations between infant temperament and coparenting. Thus, we were able to test whether infant temperament predicted change in coparenting behavior over the first year, and whether coparenting behavior predicted change in infant temperament across the same period (Figure 1). Moreover, we were also able to test whether early infant temperament moderated stability in coparenting over the first year.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model depicting the reciprocal relations between infant temperament and coparenting behavior over time.

Although the limited existing research has produced mixed findings, the weight of the evidence suggests that temperamentally difficult infants present challenges for family relationships more generally (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003), and that even parents who compensate for a difficult infant may not be able to sustain their adaptive response over time (Sanson & Rothbart, 1995). Therefore we hypothesized that higher levels of infant difficulty would portend decreases in supportive and increases in undermining coparenting behavior over time. Although we also tested whether early coparenting behavior forecasted change in infant temperament over time, no research has found effects of coparenting on the behavior of such young children; thus, we did not advance specific predictions. Finally, given previous research indicating that infant temperament may play an indirect role in relation to coparenting (McHale et al., 2004; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007), we hypothesized that infant temperament would moderate stability in coparenting across the first year of life. Specifically, we anticipated that more difficult infants would have parents whose coparenting showed less stability over the first year. The rationale for this prediction is that difficult infants may disrupt the maintenance of coparenting behavior patterns, given diversity in how parents handle a difficult infant, with some parents adapting well and others not (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003).

METHODS

Participants

Participants in this study were 56 two-parent families who took part in a short-term longitudinal study of family transitions conducted in a small Midwestern city and surrounding area. These participants were a subsample of a larger sample of 97 families with married or cohabiting parents who were originally recruited during the third trimester of pregnancy from childbirth education classes, and through local businesses, local newspapers, and newsletters. These 97 couples were assessed during the third trimester and at 3.5 months postpartum. The 56 families whose data are considered in this report were those who also participated in a follow-up at 13 months postpartum and provided complete data on coparenting behavior and infant temperament. Attrition from the 3.5-month to 13-month assessments was primarily due to geographic relocation, and unwillingness of some families who lived farther away to travel to the campus laboratory (previous assessments had been home-based).

For the subsample of 56 families, upon enrollment into the study expectant mothers’ ages ranged from 22 to 42 years with a mean age of 28.92 years (SD = 4.30 years), and expectant fathers’ ages ranged from 22 to 45 years with a mean age of 31.22 years (SD = 5.63 years). The median family income was $51,000 – 61,000 per year (Range = $11,000–20,000 to over $100,000). Ninety-three percent of expectant mothers and 79% of expectant fathers had obtained at least a college degree (Range = some college to doctoral degree for expectant mothers; Range = some high school to doctoral degree for expectant fathers). Eighty-five percent of the participants were European American, 6% Hispanic, 5% African American, 1% Asian, and 3% of mixed race/ethnicity. All couples were married or cohabiting (98% married) and had been living together on average for 3.82 years (range = 0 to 13 years, SD = 2.86 years). Of these 56 couples, 26 (46%) became parents of girls, and 30 became parents of boys. All infants were full-term, single, and healthy. For thirty-seven of the couples (66%) this was their first child; for the remainder, one or both members of the couple were already parents. The subsample that completed the 13-month follow-up did not differ from the full sample on any demographic characteristics or on measures of coparenting behavior (described below).

Procedures

Families were scheduled for a home-based assessment when their infants were approximately 3.5 months old (M = 3.62 months, SD = 9.48 days). At the home visit, parents and their infants participated in a series of videotaped interactive episodes including two triadic family interaction episodes which took place at the end of the assessment. In the first episode, couples were given an infant jungle gym and were asked to “play together with your baby as you normally would.” These 5-minute episodes were designed to elicit typical patterns of coparenting behavior in a non-stressful situation. In the second episode, couples were given a “onesie” (infant bodysuit) and were asked to change the infant's clothes together. This task was designed to assess coparenting behavior in an arguably more stressful situation - joint completion of a child care task. These episodes lasted on average for 3.42 minutes (range: 1.43 to 8.37 minutes). Both types of interactions were coded for coparenting behavior as detailed below.

When infants were 13 months old (M = 13.49; SD = .81), they visited the laboratory with their parents. At this assessment, infants and their parents were videotaped while playing together with age-appropriate toys for 20 minutes. During the first 10 minutes, families were asked to play first with a set of stacking rings, second with a shape sorter, and third with blocks, although parents were told that they could play with the toys out of order if they judged it appropriate. Within the second 10 minutes, families played together for 5 minutes with a new box of toys (e.g., plastic telephones, a jack-in-the-box). Finally, parents were asked to help the infant clean up the toys. These interactions were also coded for coparenting behavior.

Measures

Infant temperament at 3.5 and 13 months

At both time points, mothers and fathers independently completed the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (ICQ; Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, 1979), a 28-item survey which measures four aspects of difficult temperament: fussiness, unadaptability, dullness, and unpredictability. For the purposes of this study, we averaged the items comprising the four subscales (separately by respondent and time point) to create composite scores reflecting mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of infant difficult temperament at 3.5 months and 13 months. Cronbach’s alphas for mothers’ perceptions of difficult temperament were .77 and .82 at 3.5 and 13 months, respectively, and alphas for fathers’ perceptions of difficult temperament were .82 at 3.5 months and .78 at 13 months. Although mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of difficult temperament were significantly correlated (r = .52, p < .01 at 3.5 months and r = .59, p < .01 at 13 months), we chose not to combine parents’ ratings given the notion that children may behave differently with mothers and fathers (Mangelsdorf, Schoppe, & Buur, 2000), and in light of previous research that has found mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of infant temperament to be differentially related to coparenting (Van Egeren, 2004).

Coparenting behavior at 3.5 and 13 months

The family interaction episodes at both time points were coded for aspects of coparenting behavior using a subset of scales developed by Cowan and Cowan (1996) and used in previous work on coparenting (Schoppe Mangelsdorf, & Frosch, 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007). “Coparenting incidents,” according to Belsky, Crnic, and Gable (1995), are instances in which one parent either supports and/or undermines the other parent’s parenting goals or intentions. Thus, coparenting reflects partners’ behaviors toward each other in reference to the infant, but does not directly include individual parent behavior toward the infant, infant behavior, or marital behavior. At each time point coding was completed by a team of two coders who rated the overall nature of coparenting incidents within each of the episodes (the play and clothes-change episodes at 3.5 months; the two 10-minute play episodes at 13 months) using the scales described below. The coding teams were different at 3.5 months and 13 months, and the 13-month coders were unaware of the 3.5-month ratings. Each coder was randomly assigned half of the tapes to code, except for the randomly selected tapes that both coders rated for reliability purposes. Coder discrepancies for the double-coded tapes were resolved through conferencing.

The dimensions rated were: pleasure (parents’ enjoyment of coparenting), warmth (affection and emotional support between parents), cooperation (extent to which parents provide help and instrumental support to each other), displeasure (degree to which parents do not enjoy working together), coldness (emotional distance or disdain between parents), anger (hostility or irritation between parents), and competition (parents’ efforts to “outdo” each other when working with the infant). All dimensions were coded on 5-point scales (1 = very low; 5 = very high).

At 3.5 months, coders overlapped on 23% of the videotapes. Percent agreement within one scale point was 100% for all scales across episodes. The gamma statistic was also used to assess interrater reliability because it controls for chance agreement like kappa but is more appropriate for ordinal data (Hays, 1981; Liebetrau, 1983). Gammas ranged from .76 to .98 (M = .92). At 13 months, coders overlapped on 31% of the videotapes. Percent agreement within one scale point ranged from 90–98% (M = 94%). Gammas ranged from .75 to .95 (M = .84).

At each time point, ratings for each scale across the two episodes were combined to yield one score per family for pleasure, warmth, and so forth. Further data reduction was conducted on a conceptual basis (see Schoppe et al., 2001), by combining the three scales that assessed supportive coparenting behavior (pleasure, warmth, cooperation; standardized alpha at 3.5 months = .88; at 13 months = .92), and combining the four scales that assessed undermining coparenting behavior (displeasure, coldness, anger, and competition; standardized alpha at 3.5 months = .64; at 13 months = .79). At both Time 1 and Time 2 these two composite variables were significantly correlated (r = −.28, p < .05 at 3.5 months; r = −.66, p < .01 at 13 months), but were maintained separately consistent with conceptualizations emphasizing the distinctness of supportive and undermining coparenting (Belsky et al., 1996; McHale, 1995; Schoppe et al., 2001; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004).

Parents rated high on supportive coparenting demonstrated an affectionate connection as parents and clearly enjoyed watching each other interact with their infant. Such parents also tended to build upon each other's efforts when working with their infant. Parents rated low on supportive coparenting did not seem to enjoy or appreciate each other’s relationship with their infant, and seemed disconnected from each other, often interacting with the infant independently. A family that received a high score for undermining coparenting was one in which the parents expressed disapproval or dislike of each other’s parenting strategies with an affectively charged, negative tone. Parents in this type of family also tended to interfere behaviorally with each other’s parenting efforts or compete with each other for their infant’s attention. In contrast, parents receiving low scores for undermining coparenting did not express disapproval of each other’s parenting or interfere with each other’s parenting or relationship with their child.

RESULTS

Data analysis was conducted in several steps. First, analyses testing for differences in the variables of interest by parent status (first-time versus experienced) and infant gender were conducted. We also tested for mean-level differences in coparenting behavior from 3.5 to 13 months. Next, correlations among supportive and undermining coparenting behavior and parents’ perceptions of infant difficulty at 3.5 and 13 months were computed. Subsequently, a series of cross-lag correlation models was conducted using path analysis to determine whether infant difficulty predicted change in coparenting behavior over the first year, and whether coparenting behavior predicted change in infant temperament. Finally, regression analyses were used to test whether infant difficulty moderated stability in coparenting behavior across the first year.

Preliminary Analyses

T-tests revealed one significant difference in coparenting behavior when comparing families of boys versus girls: parents of female infants demonstrated higher levels of supportive coparenting at 13 months (M = 20.71; SD = 4.61) than parents of male infants (M = 18.10; SD = 3.59), t(54) = 2.38, p < .05. One significant difference also emerged when comparing first-time parents to those who already had prior parenting experience, such that first-time mothers perceived their infants as less temperamentally difficult (M = 2.64; SD = .56) than experienced mothers (M = 3.01; SD = .64), t(54) = −2.22, p < .05, but only at 13 months. Despite few significant relations of parent status and infant gender with infant temperament and coparenting behavior, these variables were controlled for in subsequent analyses. Although there was no significant difference in levels of supportive coparenting demonstrated by parents at the two time points, parents engaged in significantly more undermining behavior at 13 months (M = 12.22; SD = 4.07) than at 3.5 months (M = 9.29; SD = 1.88), t(55) = 6.04, p < .01.

Correlations among coparenting behavior and infant temperament at 3.5 and 13 months (Table 1) revealed that both supportive and undermining coparenting showed significant stability across the infant's first year, as did mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty. Consistent with a previous paper (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007), there were only a few associations between parents’ perceptions of temperament and coparenting behavior at 3.5 months. In the analyses conducted for the current study, when mothers perceived their infants as more difficult, parents showed less supportive coparenting, but when fathers perceived their infants as more difficult, parents also demonstrated less undermining behavior. There was also one significant correlation linking coparenting behavior at 3.5 months to infant temperament at 13 months: when parents showed greater supportive coparenting at 3.5 months, fathers perceived their infants as less difficult at 13 months.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics for Infant Temperament and Coparenting Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | M | SD | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5-Month Assessment | |||||||||||

| 1. Mothers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty | .52** | −.26* | −.18 | .38** | .45** | .02 | .02 | 2.65 | .55 | 56 | |

| 2. Fathers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty | −.02 | −.33* | .27* | .47** | −.18 | −.05 | 2.82 | .56 | 56 | ||

| 3. Supportive Coparenting Behavior | −.28* | −.08 | −.36** | .27* | −.26* | 19.35 | 3.67 | 56 | |||

| 4. Undermining Coparenting Behavior | −.06 | −.19 | −.18 | .46** | 9.29a | 1.88 | 56 | ||||

| 13-Month Assessment | |||||||||||

| 5. Mothers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty | .59** | .13 | .05 | 2.77 | .61 | 56 | |||||

| 6. Fathers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty | −.08 | −.10 | 2.87 | .53 | 51 | ||||||

| 7. Supportive Coparenting Behavior | −.66** | 19.31 | 4.26 | 56 | |||||||

| 8. Undermining Coparenting Behavior | 12.22a | 4.07 | 56 | ||||||||

Note. Five fathers did not complete the measure of infant temperament at 13 months. It should be noted that these five fathers’ ratings of infant difficulty at 3.5 months were not significantly different than the 3.5-month ratings of fathers who did complete the temperament measure at 13 months. Corresponding subscripted letters indicate a significant mean-level difference at p < .01.

p < .05

p < .01.

Cross-Lag Correlation Models of Relations between Infant Temperament and Coparenting

Path analysis was conducted using AMOS 16.0 to estimate cross-lag correlation models of the associations between infant temperament and coparenting behavior across time (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Specifically, four models were tested. The first two models examined cross-time relations between mothers’ perceptions of infant difficulty and supportive and undermining coparenting, respectively. The second two models considered the analogous cross-time relations between fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty and supportive and undermining coparenting. All models controlled for infant gender and parent status. We report several commonly used measures of overall model fit: the chi-square test, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). However, consistent with our hypotheses, we were most interested in the significance of the path coefficients – particularly those linking infant difficulty at 3.5 months with coparenting at 13 months, and those linking coparenting at 3.5 months with infant difficulty at 13 months. Models in which these paths were not significant are described only briefly.

The first model, which considered longitudinal relations between mothers’ reports of infant difficulty and supportive coparenting behavior, provided a good fit for the data, χ2 (5, N = 56) = 4.88, p =.43, RMSEA = .000, CFI = 1.00. Mothers’ reports of difficult temperament demonstrated significant stability over time, as did supportive coparenting behavior. However, neither cross-lag path linking infant temperament with supportive coparenting was significant. Similarly, the second model, which examined longitudinal relations between mothers’ reports of infant difficulty and undermining coparenting behavior, provided a good fit for the data, χ2 (5, N = 56) = 4.59, p =.47, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00. Again, in the context of significant stability in infant temperament and undermining coparenting, neither cross-lag path linking temperament with undermining coparenting was significant.

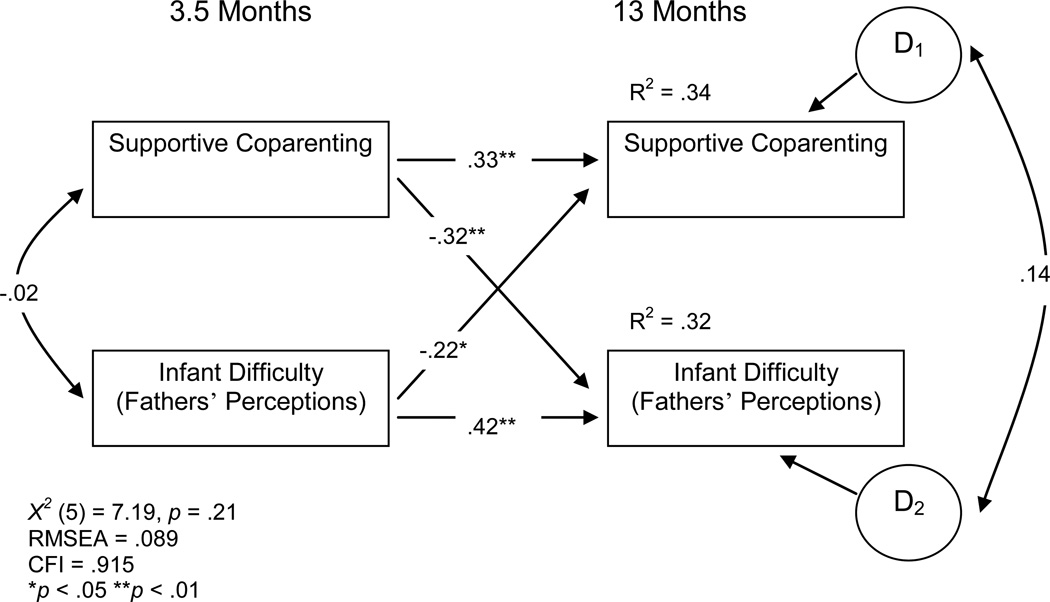

The third model tested longitudinal relations between fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty and supportive coparenting behavior, and also yielded an adequate fit, χ2 (5, N = 56) = 7.19, p =.21, RMSEA = .089, CFI = .915. Results for this model are shown in Figure 2. In addition to significant stability in both infant temperament and supportive coparenting, the path linking fathers’ reports of infant difficulty at 3.5 months and supportive coparenting behavior at 13 months was significant, β = −.22, p < .05, as was the path linking supportive coparenting at 3.5 months and infant difficulty at 13 months, β = −.32, p < .01. Thus, in this model, early infant difficulty predicted decreases in supportive coparenting behavior from 3.5 to 13 months, whereas early supportive coparenting behavior predicted decreases in infant difficulty from 3.5 to 13 months. The fourth and final model examined the cross-time relations between fathers’ reports of temperament and undermining coparenting behavior. Although the model fit well, χ2 (5, N = 56) = 5.98, p =.31, RMSEA = .059, CFI = .962, and stability in temperament and coparenting was apparent, the cross-lag paths of interest did not attain statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Path analysis results for the model testing longitudinal relations between fathers’ perceptions of infant difficult temperament and supportive coparenting behavior.

Regression Analyses Testing Infant Temperament as a Moderator of Stability in Coparenting

In order to investigate the role infant temperament may play as a moderator of stability in coparenting, a series of hierarchical regression equations was computed. First, two equations were computed predicting supportive coparenting behavior at 13 months from supportive coparenting behavior at 3.5 months and mothers' and fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty at 3.5 months, respectively. Similarly, two equations were computed predicting undermining coparenting behavior at 13 months from undermining coparenting behavior at 3.5 months and mothers’ or fathers’ perceptions of infant difficult temperament at 3.5 months. On the first step of each equation, parent status and infant gender were entered as control variables. On the second step, supportive or undermining coparenting behavior at 3.5 months, mothers’ or fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty at 3.5 months, and the 2-way interaction between 3.5-month coparenting and temperament were entered as a block. If a significant interaction was obtained, it was graphed and probed according to procedures detailed in Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006).

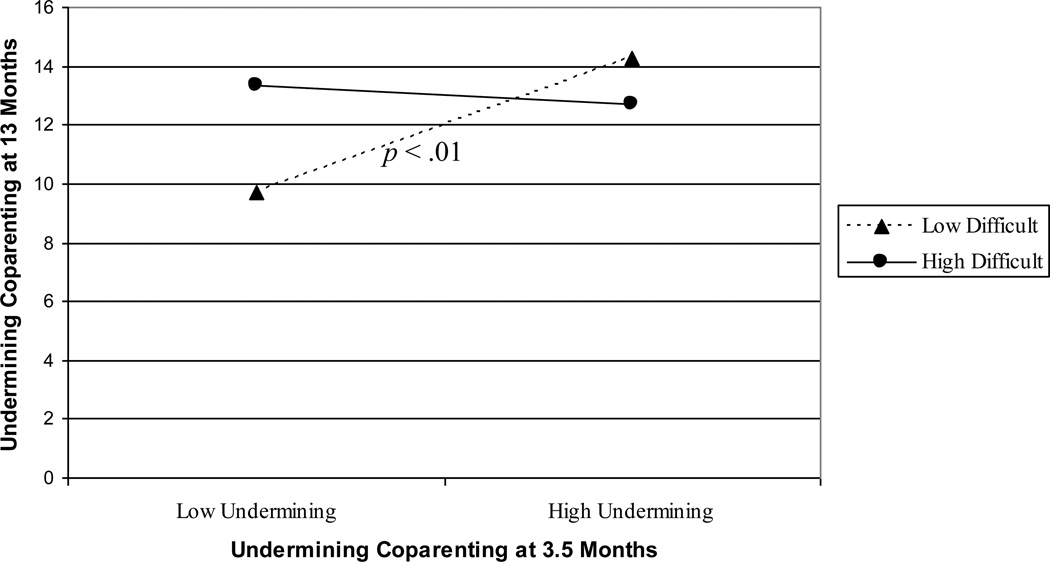

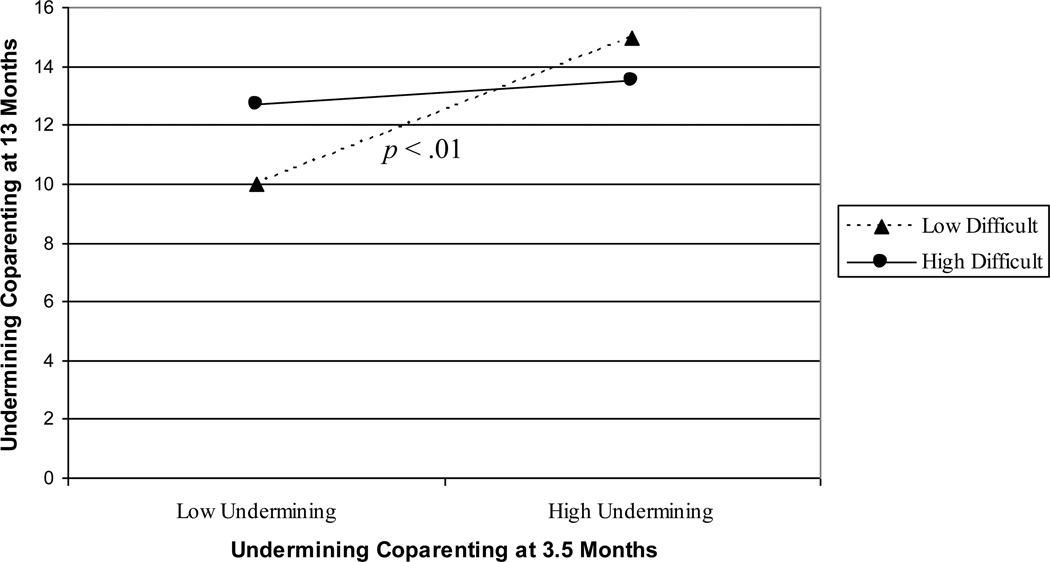

When testing whether infant temperament moderated stability in supportive coparenting behavior, none of the 3.5-Month Supportive Coparenting × Temperament interactions was significant. In contrast, both fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of infant difficulty appeared to moderate stability in undermining coparenting (see Table 2). The significant interaction between undermining coparenting and fathers’ perceptions of infant difficulty at 3.5 months, β = −.42, p < .01, is depicted in Figure 3. A simple slopes analysis indicated that the slope of the line representing low levels of infant difficult temperament was significantly different from zero, t = 4.66, p < .01, whereas the slope of the line representing high levels of infant difficult temperament was not, t = −.35, ns. A similar moderating effect was found for mothers’ perceptions of infant difficulty, β = −.26, p = .06 (Figure 4), although this effect only approached significance. A simple slopes analysis of this interaction confirmed that the slope of the line indicating low levels of infant difficulty was significantly different from zero, t = 4.34, p < .01, whereas the slope of the line indicating high levels of infant difficulty was not, t = .45, ns. Taken together, these interaction effects indicate that early undermining coparenting predicted later undermining coparenting only when infants were lower in perceived temperamental difficulty.

Table 2.

Regressions Testing Infant Temperament as a Moderator of Stability in Undermining Coparenting from 3.5 to 13 Months

| Variable(s) Entered at Each Step | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | F | df | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infant Gender | 1.61 | 1.09 | .20 | ||||||||

| Parent Status | −2.17 | 1.15 | −.26+ | .08 | |||||||

| 2. Undermining Coparenting at 3.5 Months | .77 | .28 | .35** | ||||||||

| Mothers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty at 3.5 Months | .56 | .91 | .08 | ||||||||

| Undermining Coparenting × Infant Difficulty | −1.00 | .52 | −.26+ | .26 | |||||||

| 5.09** | 5,50 | ||||||||||

| 1. Infant Gender | 1.61 | 1.09 | .20 | ||||||||

| Parent Status | −2.17 | 1.15 | −.26+ | .08 | |||||||

| 2. Undermining Coparenting at 3.5 Months | .52 | .31 | .24 | ||||||||

| Fathers’ Perceptions of Infant Difficulty at 3.5 Months | .92 | .86 | .13 | ||||||||

| Undermining Coparenting × Infant Difficulty | −1.22 | .40 | −.42** | .32 | |||||||

| 6.79** | 5,50 | ||||||||||

p <.10

p < .05

p < .01.

Figure 3.

Fathers’ perceptions of infant difficult temperament moderate stability in undermining coparenting behavior.

Figure 4.

Mothers’ perceptions of infant difficult temperament moderate stability in undermining coparenting behavior.

DISCUSSION

Results from the present study clarify and extend previous research by further elucidating the relations between infant temperament and coparenting behavior across the infant’s first year. On the whole, our findings revealed that relations between infant temperament and coparenting behavior may be both direct and indirect; as well, coparenting behavior may have a reciprocal effect on infant temperament. These findings support theoretical models emphasizing reciprocal influences between parents and children (Bell, 1968; Minuchin, 1974; Sameroff, 1975), ideas that have been relatively understudied in relation to infants' roles in the coparenting relationship. Thus, given the burgeoning literature linking coparenting dynamics to children's adjustment (McHale et al., 2002), it appears that children themselves may play a role in the early course of the family processes that shape their development.

Although significant findings with respect to direct longitudinal relations between temperament and coparenting were not numerous, we did obtain evidence for bidirectional effects. In particular, early infant difficulty, as reported by fathers, was associated with a decrease in supportive coparenting behavior over time; conversely, early supportive coparenting behavior was associated with a decrease in infant difficulty. These findings emerged despite moderate stability in both supportive coparenting and infant temperament. It seems that there are two processes simultaneously at work during this time period; difficult infants seem to disrupt the coparenting relationship, while supportive coparenting may help infants become easier to care for, or may lead fathers to perceive them as such. With respect to the association between early temperament and change in coparenting behavior, our finding corroborates the limited research which suggests that difficult infants may challenge the coparenting system (Lindsey et al., 2005; Van Egeren, 2004). With respect to the latter finding, to our knowledge no published research has obtained results consistent with the notion that coparenting affects infant behavior during early infancy. However, recent work has provided intriguing evidence that marital dynamics may indeed affect infant emotion regulation (Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Lekka, 2007).

It is noteworthy that fathers’ (and not mothers’) perceptions of infant temperament were the context for these bidirectional relations. Van Egeren (2004) also found that fathers who perceived their infants as more difficult reported more negative coparenting experiences, and the same was not true for mothers. It may be the case that fathers’ parenting or involvement in childrearing mediates these relations. Some research suggests that fathers’ involvement may be more susceptible to influences of child characteristics than mothers’ (McBride, Schoppe, & Rane, 2002), consistent with the notion that active parenting is more “elective” for fathers than for mothers (Doherty, Kouneski, & Erickson, 1998). If fathers are backing away from parenting difficult infants, a decrease in support between coparents may be a logical outcome. The reciprocal relationship, or that between early supportive coparenting and decreases in father-perceived infant difficulty can be understood through the lens of the fathering vulnerability hypothesis (Goeke-Morey & Cummings, 2007), which suggests that father-child relationships may be particularly susceptible to spillover effects of marital or coparental dynamics. Indeed, it could be that fathers who are supported by their partners are more sensitive and involved parents whose infants come to exhibit less difficult behavior, or come to be perceived by their fathers as easier to manage. Regardless, our findings suggest that fathers’ perceptions of infant temperament may have particular relevance in the context of the coparenting relationship, and we recommend that future research not neglect the father’s perspective.

Furthermore, as anticipated, the extent to which coparenting dynamics persisted over time depended in part on the infant's temperament. Infants with less difficult temperaments had parents whose levels of undermining coparenting behavior were remarkably stable across the first year, whereas the parents of more difficult infants showed much greater variability across time in their levels of undermining behavior. The most likely reason for this finding is that some parents, even those who experience initial difficulty in coparenting, are able to eventually pull together around a difficult infant, whereas others who do not show immediate coparenting difficulties may later fall apart when faced with a challenging infant (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007). These diverse responses to a difficult infant (see Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003) may explain the instability in undermining behavior. In contrast, families with less difficult infants may not need to adjust their coparenting patterns, so their early behaviors persist over time. Why infant temperament did not similarly moderate stability in supportive coparenting is not clear; perhaps characteristics of parents (rather than infants) are more influential in this regard. Future research should continue to investigate factors that may interact with infant temperament in relation to coparenting. Although previous research indicates that marital quality plays an important role in the establishment of initial coparenting patterns for parents of difficult infants (McHale et al., 2004; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007), understanding stability and change in coparenting will likely require consideration of other factors as well.

Other aspects of this study's findings invite further research into how children's characteristics may affect coparenting dynamics. Although the differences were not particularly consistent, we did find some evidence for effects of child gender and developmental level, such that parents of one-year-old girls were observed to engage in more supportive coparenting behavior than parents of one-year-old boys, and undermining coparenting behavior increased from 3.5 months to 13 months. Glimpses of direct and indirect effects of child gender (Lindsey et al., 2005; Margolin et al., 2001; McHale, 1995) and developmental level (Gable et al., 1995; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004) on coparenting have emerged in a number of studies, but findings have been quite mixed, and thus difficult to interpret. To achieve a more complete understanding of how children's characteristics may affect coparenting, more theoretically-driven, nuanced investigations are needed.

The current study’s results suggest that early assessment and intervention with families, particularly with families of temperamentally difficult infants, may be essential as coparenting patterns appear susceptible to infant behavior in such families. Prior research suggests that strengthening the marital or couple relationship prior to a child's birth, a time when couples may be particularly motivated (Fivaz-Depeursinge & Favez, 2006), may help to insulate emerging coparenting relationships from the negative effects of a difficult infant (McHale et al., 2004; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2007). However, the present study further indicates that the early postpartum period may be critical as well, as early coparenting seems to fluctuate more for parents of a difficult infant. Our findings also suggest the importance of the early establishment of supportive coparenting, and the consideration of fathers’ perspectives on infant behavior. However, whether the focus is on the prebirth or early postpartum periods, practitioners should work not just to establish adaptive initial patterns of family functioning across the transition to parenthood, but adaptive patterns that will remain stable across the child's first year(s).

A key strength of this study was the longitudinal design, which followed infants and their families from the early postpartum period through the end of the first year, and thus allowed us to consider questions regarding relations between infant temperament and coparenting over time. Moreover, the observations of coparenting behavior captured family dynamics across home and laboratory contexts and in both structured and more unstructured situations. Although these observations were brief, they did reveal significant stability in coparenting behavior and bidirectional relations between temperament and coparenting; perhaps the varied demands placed on parents and their infants by study procedures helped provide a holistic picture of coparental functioning. However, other researchers have emphasized the importance of parent-report or interview methods for assessing coparenting relationships in conjunction with observational measures (McHale & Rotman, 2007); thus, the inclusion of parents' perspectives on coparenting may have strengthened or qualified these findings.

Our study also benefitted from the inclusion of both mothers’ and fathers’ reports of infant temperament. Clearly, parent reports of temperament can be subject to biases (Seifer, 2002), even as parents have access to a wealth of information concerning their infants' behavior. Thus, as we have discussed, it is not clear whether the effects we obtained are attributable to actual infant temperament or parents’ perceptions of their infant’s temperament. The inclusion of laboratory assessments of temperament or reports by trained observers would strengthen future research. Moreover, the use of measures that allow for finer distinctions between different dimensions of infant temperament may facilitate a more nuanced understanding of relations between infant temperament and coparenting.

Additional limitations of this work stem from the nature of the sample. Although somewhat more diverse in race/ethnicity and income than many other studies of early coparenting dynamics, participants in this study were mostly white, well-educated, relatively affluent, and married. As a result, our findings may not apply to families who fall outside of the parameters of this sample. Moreover, the sample was fairly small, which limited statistical power, particularly in detecting discrepancies between our cross-lag models and our data. However, the pathways of influence in the model were still significant, and it is these pathways which were the focus of the hypotheses. In our view, this limitation makes our significant findings with respect to both bidirectional influences and moderation particularly noteworthy.

In sum, these findings provide empirical support for bidirectional and transactional models of development, which have long argued that infants and parents influence each other. In particular, relations between infant temperament and coparenting appear to take both direct and indirect forms across the first year of life. To the extent that infant behavior does affect the coparenting relationship, infants may be in part driving their own development as well as influencing the developmental course of family relationships over time. In the service of informing both research and practice, future investigations should further examine the infant's role, as well as the roles of other family and parent characteristics, in affecting the ease with which families navigate the transition to parenthood via the establishment and maintenance of a healthy parenting partnership.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

This investigation is part of a longitudinal study of family development conducted at the University of Illinois, and was funded by support for the second author’s dissertation research from the University of Illinois. We wish to thank the families who participated in this study and the individuals who contributed to data collection and coding, especially Kathy Anderson, Katie Bliss, Catherine Buckley, Brieanne Kraft, and Margaret Szewczyk Sokolowski.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented at the 2007 Society for Research in Child Development biennial meeting, Boston, MA.

Contributor Information

Evan F. Davis, The Ohio State University

Sarah J. Schoppe-Sullivan, The Ohio State University.

Sarah C. Mangelsdorf, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Geoffrey L. Brown, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

REFERENCES

- Bates JE, Freeland CAB, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families (New Directions for Child Development, Vol. 74) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman JM, Alberts AE, Carleton ME, McHale JP. Are there links between infant temperament and coparenting processes at 3 months post-partum?; Paper presented at the World Association for Infant Mental Health world congress; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bonds DD, Gondoli DM. Examining the process by which marital adjustment affects maternal warmth: The role of coparenting support as a mediator. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:288–296. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Schoolchildren and their families project: Description of co-parenting style ratings. Berkeley: University of California; 1996. Unpublished coding scales. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Leerkes E. Infant negative emotionality, caregiving, and family relationships. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, Lekka SK. Pathways from marital aggression to infant emotion regulation: The development of withdrawal in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Beaton JM. Mothers and fathers parenting together. In: Vangelisti AL, editor. Handbook of family communication. 2004. pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Kouneski EF, Erickson MF. Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Favez N. Exploring triangulation in infancy: Two contrasted cases. Family Process. 2006;45:3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Frascarolo F, Corboz-Warnery A. Assessing the triadic alliance between fathers, mothers, and infants at play. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families (New Directions for Child Development, Vol. 74) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 27–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch CA, Mangelsdorf SC, McHale JL. Marital behavior and the security of preschooler-parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:144–161. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Belsky J, Crnic K. Coparenting during the child’s 2nd year: A descriptive account. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Impact of father involvement: A closer look at indirect effects models involving marriage and child adjustment. Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hays WL. Statistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liebetrau AM. Measures of association. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey EW, Caldera Y, Colwell M. Correlates of coparenting during infancy. Family Relations. 2005;54:346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Schoppe SJ, Buur H. The meaning of parental reports: A contextual approach to the study of temperament and behavior problems in childhood. In: Molfese VJ, Molfese DL, editors. Temperament and personality development across the lifespan. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:3–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe SJ, Rane TR. Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:998–1011. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:985–996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. When infants grow up in multiperson relationship systems. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:370–392. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Johnson D, Sinclair R. Family dynamics, preschoolers’ family representations, and preschool peer relationships. Early Education and Development. 1999;10:373–401. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, Lieberson R. The transition to coparenthood: Parents’ prebirth expectations and early coparental adjustment at 3 months postpartum. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:711–733. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Khazan I, Erera P, Rotman T, DeCourcey W, McConnell M. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting (2nd ed., Vol. 3): Being and becoming a parent. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Rasmussen JL. Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:39–59. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Rotman T. Is seeing believing? Expectant parents’ outlooks on coparenting and later coparenting solidarity. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. Transactional models in early social relations. Human Development. 1975;18:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Rothbart MK. Child temperament and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting, Vol. 4: Applied and practical parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA. Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers’ externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:526–545. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Brown GL, Sokolowski MS. Goodness-of-fit in family context: Infant temperament, marital quality and early coparenting behavior. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA, McHale JL. Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:194–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R. What do we learn from parent reports of their children's behavior? Commentary on Vaughn et al.'s critique of early temperament assessments. Infant Behavior and Development. 2002;25:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA. Prebirth predictors of coparenting experiences in early infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:278–295. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA. The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:453–477. [Google Scholar]