Abstract

We have previously reported on the inhibition of HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor α)-regulated pathways by HEXIM1 [HMBA (hexamethylene-bis-acetamide)-inducible protein 1]. Disruption of HEXIM1 activity in a knock-in mouse model expressing a mutant HEXIM1 protein resulted in increased susceptibility to the development of mammary tumours, partly by up-regulation of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) expression, HIF-1α expression and aberrant vascularization. We now report on the mechanistic basis for HEXIM1 regulation of HIF-1α. We observed direct interaction between HIF-1α and HEXIM1, and HEXIM1 up-regulated hydroxylation of HIF-1α, resulting in the induction of the interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL (von Hippel–Lindau protein) and ubiquitination of HIF-1α. The up-regulation of hydroxylation involves HEXIM1-mediated induction of PHD3 (prolyl hydroxylase 3) expression and interaction of PHD3 with HIF-1α. Acetylation of HIF-1α has been proposed to result in increased interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL and induced pVHL-mediated ubiquitination, which leads to the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α. HEXIM1 also attenuated the interaction of HIF-1α with HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1), resulting in acetylation of HIF-1α. The consequence of HEXIM1 down-regulation of HIF-1α protein expression is attenuated expression of HIF-1α target genes in addition to VEGF and inhibition of HIF-1α-regulated cell invasion.

Keywords: breast cancer, hexamethylene-bis-acetamide-inducible protein-1 (HEXIM1), hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), histone deacetylase (HDAC), prolyl hydroxylase (PHD)

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancers and other solid tumours are susceptible to hypoxia because they proliferate and outgrow vascular supplies of oxygen and nutrients [1]. The main regulator that orchestrates the cellular response to hypoxia is HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor 1), a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of α- and β-subunits critical for adaptive responses to reduced oxygen [2]. Overexpression of HIF-1α protein in breast cancer correlates with poor prognosis, increased risk of metastasis and decreased survival [3]. The critical role HIF-1α in tumour metastasis arises from the fact that it is a potent activator of angiogenesis, invasion and metabolic reprogramming through its up-regulation of target genes important for these functions {e.g. VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), EMC-degrading proteases and GLUT1 (glucose transporter 1), see [4]}. HIF-1α is also a mediator of the effects of the tumour microenvironment on the metastatic behaviour. HIF-1α plays a critical role in the generation of the ‘pre-metastatic niche’ to which the tumour cells metastasize through the recruitment of BMDCs (bone-marrow-derived cells). It has also been proposed that hypoxia stimulates expansion of normal and cancer stem cells [5]. The HIF-1α pathway is thus an ideal target for cancer therapy, since interfering with a master regulator of the hypoxic response could disrupt multiple processes essential for tumour cell self-renewal, expansion, dissemination and metastatic colonization.

The clinical benefits of anti-VEGF therapy are relatively modest and usually measured in weeks or months [6]. In some cases, patients do not respond to anti-VEGF treatments. Hypoxic regions of tumours are believed to be the source of tumour cells that are resistant to radiation, chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic treatment [3]. Antiangiogenic agents efficiently prune tumour vessels and cause hypoxia [7]. However, metabolic reprogramming to glucose addiction allows tumour cells to generate energy in hypoxic conditions and for tumour stem cells in hypoxic niches to escape anti-angiogenic treatment [7]. Increased intratumour hypoxia also results in the production of redundant angiogenic factors by tumours and acquisition of a more invasive phenotype. HIF-1α is a major regulator of these angiogenic actors following hypoxia, and regulates several genes involved in angiogenesis, proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, pericyte recruitment, modification of vascular permeability and recruitment of BMDCs [8]. Thus targeting HIF-1α rather than VEGF may offer advantages in late-stage breast cancer.

Regulation of HIF-1α stability is mediated by the ODD (oxygen-dependent degradation) domain through various post-translational modifications [9]. HIF-1α is hydroxylated at Pro402 and Pro564 by a family of HIF PHD (prolyl hydroxylase) domain proteins, which require O2 [10,11]. Hydroxylated HIF-1α subsequently interacts with the tumour suppressor pVHL (von Hippel–Lindau protein), which targets it for proteasomal degradation [9,12]. ARD1 (arrest-defective protein 1) is another enzyme proposed to modify HIF-1α by acetylating the Lys532 residue in the ODD domain of HIF-1α [13]. Acetylation of HIF-1α has been reported to result in increased interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL and induced pVHL-mediated ubiquitination, which leads to the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α [13]. However, the functional relevance of HIF-1α acetylation remains controversial.

We have recently reported that re-expression of HMBA (hexamethylene-bis-acetamide)-inducible protein 1 HEXIM1 through transgene expression or polymer-mediated delivery of HMBA inhibited metastasis in a mouse model of metastatic mammary cancer that can be correlated with decreased expression of HIF-1α, VEGF, compensatory pro-angiogenic factors and vascularization [14]. We now report that HEXIM1 directly regulates HIF-1α protein stability by up-regulating hydroxylation, interaction with pVHL and ubiquitination of HIF-1α. HEXIM1 also regulated HIF-1α acetylation by attenuating its interaction with HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1). As a result, HEXIM1 is able to regulate expression of HIF-1α target genes and HIF-1α-induced cell invasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Antibodies against the following were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology: CXCR4 (CXC chemokine receptor), HDAC1, pan-acetyl, ubiquitin and SDF-1 (stromal-cell-derived factor 1). The anti-HEXIM1 antibody was generated in the Montano laboratory [15]. Anti-HIF-1α and anti-PHD3 antibodies were obtained from OxyCell Bioresearch. The anti-VHL antibody was from BD Pharmingen. The antibody against HIF-2α and HIF-1α hydroxylated at Pro564 was obtained from Novus Biologicals. Anti-HA (haemagglutinin) and anti-tubulin antibodies were from Sigma Chemical.

Hypoxia treatment

Cells were placed in an airtight modular incubator chamber (Billup-Rothenburg, Forma Scientific) that had been equilibrated with a gas mixture containing 1 %oxygen, 5 %CO2, and 94.5 % nitrogen at 37 °C. Hypoxia treatments were for 8 h, except for experiments involving detection of HIF-1α target genes that were conducted using 16 h of hypoxia treatment.

Cell culture

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from A.T.C.C. (Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) and maintained as previously described [15]. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with control vector or expression vector for FLAG–HEXIM1 as described previously [16]. RCC4 cells (pVHL-deficient or transfected with wild-type pVHL, see [17]) were maintained as previously described [18].

RNAi

MCF7-control miRNA and MCF7-HEXIM1 miRNA cells were generated as described previously [19]. A polymerase II promoter-driven miRNA expression vector system (Invitrogen) was used. To make pcDNA-HEXIM1 miR, miRNA oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned into the pcDNA 6.2 GW/EmGFP vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MCF-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA 6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR expression vectors containing either the HEXIM1 miRNA insert or a control LacZ miRNA insert. Following blasticidin selection, cells expressing the highest level of GFP were flow-sorted and expanded. The sequence of the miRNA oligonucleotides are: miR clone 35 (forward), 5′-TGCTGTACAGTTGCT-AGTTTGAGGCTGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACAGCCTCAA-TAGCAACTGTA-3′; miR clone 35 (reverse), 5′-CCTGTAC-AGTTGCTATTGAGGCTGTCAGTCAGTGGCCAAAACAGC-CTCAAACTAGCAACTGTAC-3′; miR clone 609 (forward), 5′-TGCTGATGAGGAACTGCGTGGTGTTAGTTTTGGCCA-CTGACTGACTAACACCACAGTTCCTCAT-3′; and miR clone 609 (reverse), 5′-CCTGATGAGGAACTGTGGTGTTA-GTCAGTCAGTGGCCAAAACTAACACCACGCAGTTCCT-CATC-3′.

RT (reverse transcription)–PCR analyses

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to high (21 %) or low (1 %) oxygen conditions as indicated. All cells were subsequently subjected to RT–PCR analyses as described previously [19]. Total mRNAs were extracted using TRIzol® reagent from Invitrogen as per the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNAs were reverse transcribed using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) following the recommended protocol. cDNAs were PCR-amplified using the primers listed below. The amplified products were run on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. A 12-bit digital camera captured fluorescence and signal intensities were quantified using the Alphaimager software from Alpha Innotech.

The primers used and sequences are: HIF-1α (forward), 5′-TGCTAATGCCACCACTACC-3′; HIF-1α (reverse), 5′-TGA-CTCCTTTTCCTGCTCTG-3′; VEGF (forward), 5′-CTTTC-TGCTGTCTTGGGTG-3′; VEGF (reverse), 5′-ACTTCGTGA-TGATTCTGCC-3′; SDF1 (forward), 5′-CCGCGCTCTGCC-TCAGCGACGGGAAG-3′; SDF1 (reverse), 5′-CCTGTTTA-AAGCTTTCTCCAGGTACT-3′; CXCR4 (forward), 5′-AG-CTGTTGGCTGAAAAGGTGGTCTATG-3′; CXCR4 (reverse), 5′-GCGCTTCTGGTGGCCCTTGGAGTGTG-3′; HSulf1 (endo-sulfatase 1) (forward), 5′-GAGCCATCTTCACCCATTCAAG -3′; HSulf1 (reverse), 5′-TTCCCAACCTTATGCCTTGGGT-3′; GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (forward), 5′-TCCACTGGCGTCTTCACC-3′; GAPDH (reverse), 5′-GGCAGAGATGATGACCCTTTT-3′.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were analysed by Western blots as previously described [19]. Total protein was extracted using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were detected using their respective primary antibodies and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. GAPDH or tubulin were used as a loading control. Signals were detected using ECL Western Blotting Analysis System (GE Healthcare).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Endogenous proteins were co-immunoprecipitated and analysed as previously described [20]. MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 lysates were incubated with Protein G beads that had been preadsorbed with specific antibody or non-specific mouse IgG (as a negative control). The beads were collected by centrifugation and washed with RIPA buffer and PBS twice. After the final wash, pellets were resuspended in Western sampling buffer, and immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (10 %gel) electrophoresis. Western blot analyses were performed as described above.

ChIP assays

Cells were grown in 100-mm-diameter dishes and processed for ChIP analyses as described previously [19]. Briefly, cells were fixed with 1 % formaldehyde and lysed in SDS-lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. Lysed cells were sonicated using a Branson 450 sonicator. Clarified sonicated chromatin was diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer and used for immunoprecipitation with a given antibody. The antibody–chromatin complexes were pulled down using Protein A beads. The beads were subjected to a series of washes and the antigen–DNA complexes were eluted. The eluates were reverse cross-linked overnight at 65 °C and the DNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction. Ethanol-precipitated pellets were resuspended in water and were used as a template for PCR analysis. PCR-amplified products were run on a 2 % agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. A 12-bit digital camera captured fluorescence and signal intensities were quantified using the Alphaimager software.

In vitro translation and protein–protein interaction assays

In vitro transcription and translation of HIF-1α and HDAC1 were performed using the Promega TNT kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. GST pull-down assays were described previously [21].

Mouse model

All animal work reported in the present study was approved by the CWRU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. HEXIM1 expression was induced in mammary epithelial cells of PyMT (Polyoma Middle-T antigen) mice by mating MMTV/HEXIM1 bitransgenic mice with PyMT mice as described previously [14]. HEXIM1 expression was induced by supplementing the drinking water of mice with doxycycline at a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. MMTV/PyMT/HEXIM1 mice (±doxycycline) were killed at 17 weeks of age. Total protein from mammary tumours was extracted using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction reagent.

Invasion assays

Cell-invasion assays were performed as described previously [14]. Cell-invasion assays were performed using transwell inserts (8-mm-diameter pore size; Corning Costar) that were coated with 10 % matrigel and placed inside the wells of a 24-well plate. MDA-MB-231-control or MDA-MB-231-fl-HEXIM1 were suspended in Opti-MEM® (serum-free culture medium, Invitrogen) and placed in the upper chamber of the transwell insert (50000 cells/well). The lower chambers contained MEM (minimal essential medium) supplemented 5 % FBS. The cells were allowed to migrate to the lower chamber at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, cells invading the matrigel were fixed with 3 % paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5 %crystal violet. Invading cells were counted from five random fields per well under a microscope.

Data analyses

Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t test comparison for unpaired data. For some comparisons, probability values for the observed differences between groups were based on one-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

HEXIM1 down-regulated HIF-1α protein levels

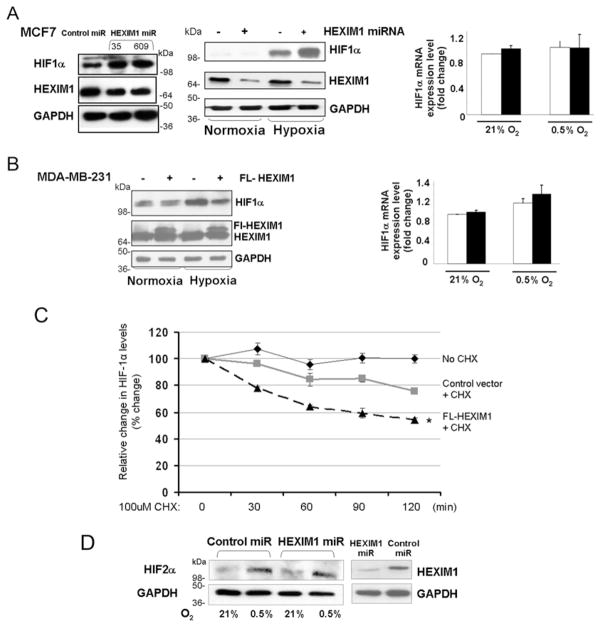

Alterations in HEXIM1 levels were achieved by transfecting breast epithelial MDA-MB-231 or MCF7 cells with control vector (or control miRNA) or expression vector for FLAG–HEXIM1 or HEXIM1 miRNA respectively. Reflecting what we observed in our previous mouse studies [16], modulation of HEXIM1 levels resulted in alterations in HIF-1α protein levels in hypoxia-treated MCF7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C). Up-regulation of HIF-1α protein levels was observed using two different miRNA clones (Figure 1A). HIF-1α protein levels were not significantly altered by HEXIM1 under normoxia. We also did not observe HEXIM1 regulation of the mRNA level of HIF-1α (Figures 1A and 1B), suggesting post-transcriptional regulation. We thus examined whether HEXIM1 regulates HIF-1α protein stability. We up-regulated expression of HEXIM1 using an expression vector for FLAG-HEXIM1. Cells were maintained under hypoxia followed by treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide for different time periods. As shown in Figure 1(C), the stability of HIF-1α protein was decreased in cells transfected with expression for FLAG-HEXIM1 compared with control transfected cells. One-way ANOVA indicates statistical significance with a P value of 0.017. We did not see alterations in HIF-2α levels as a result of down-regulation of HEXIM1 levels (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. HEXIM1 destabilizes HIF-1α protein.

(A) MCF7 cells were transfected with the expression vector for control miRNA or HEXIM1 miRNA. Shown are representative Western blots (left-hand panels, representative of five experiments) or RT–PCR (right panel, representative of three experiments) indicating HIF-1α levels under normoxia and hypoxia. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with control vector or expression vector for FLAG (FL)–HEXIM1. Shown are representative Western blots (left-hand panel, representative of four experiments) or RT–PCR (right-hand panel, representative of three experiments) indicating HIF-1α levels under normoxia and hypoxia. (C) Cells were transfected with expression vector for HEXIM1 or empty vector. The cells were incubated under hypoxia for 8 h as indicated. At the end of treatment, 100 μM cycloheximide (CHX) was added to the medium for the indicated time periods. The expression of HIF-1α and GAPDH were analysed by Western blot analysis. The density of the HIF-1α protein band was determined using an image analysis system. The values were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as percentage change relative to the time zero. Graphs show means±S.E.M. from three experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells with no CHX. Statistical significance was based on one-way ANOVA. (D) HIF-2α levels were analysed by Western blot analyses of cell extracts from MCF7 cells transfected with expression vector for control miRNA or HEXIM1 miRNA and subjected to hypoxia treatment. The results are representative of two experiments. Molecular masses in kDa are shown next to the Western blots.

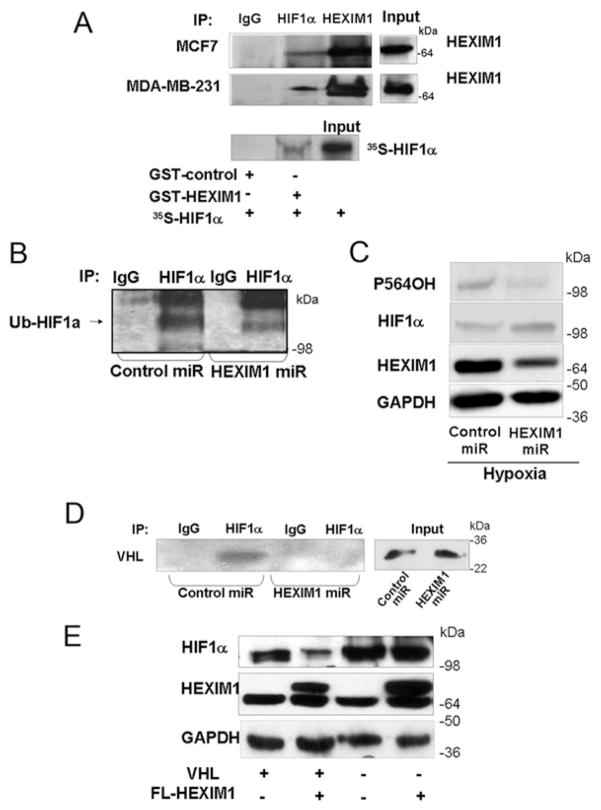

HEXIM1 interacted with HIF-1α and increased HIF-1α ubiquitination by enhancing interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL

We then determined whether HEXIM1 can act on HIF-1α directly. Using endogenous co-immunoprecipitation experiments, we observed an interaction between HEXIM1 and HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions (Figure 2A). We did not observe HEXIM1 and HIF-1α interaction under normoxic conditions (results not shown). The interaction between HEXIM1 and HIF-1α was verified using GST pull-down assays. We then examined whether HEXIM1 can regulate post-translational modifications of HIF-1α that targets HIF-1α for degradation, in particular hydroxylation and ubiquitination. We observed decreased levels of ubiquitinated and hydroxylated HIF-1α upon hypoxia treatment and down-regulation of HEXIM1 using HEXIM1 miRNA (Figures 2B and 2C). We then determined whether HEXIM1 promoted the association of HIF-1α with pVHL. Down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in attenuation of the interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL under hypoxic conditions (Figure 2D). The fact that HEXIM1 attenuation of HIF-1α protein stability involved enhanced interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL was supported by our observation that the ability of HEXIM1 to down-regulate HIF-1α protein expression was attenuated in pVHL-deficient RCC4 cells when compared with pVHL-transfected RCC4 cells (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. HEXIM1 interacted with HIF-1α and down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in decreased levels of hydroxylated and ubiquitinated HIF-1α and attenuated the HIF-1α–pVHL interaction.

(A) Upper panels, MCF7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to hypoxia treatment (8 h). Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using antibodies against HIF-1α or HEXIM1 and analysed for co-immunoprecipitating proteins by Western blotting using HEXIM1 antibody. Normal rabbit immunoglobulin was used as a specificity control. Input lanes represent 25 % of the total protein. MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 panels represent five and three experiments respectively. Lower panel, in vitro translated and [35S]methionine-labelled HIF-1α was incubated with GST or GST–HEXIM1 bound to Sepharose. Input lane represents 10 % of the total volume of in vitro translated product used in each reaction. Panels represent eight experiments. (B) Lysates from control miRNA or HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells were immunoprecipitated using anti-HIF-1α antibody and analysed by Western blotting using the indicated anti-(pan-ubiquitinated HIF-1α) (Ub-HIF1a) antibody. Cells were subjected to hypoxia and MG132 (10 uM) treatments to accumulate ubiquitinated HIF-1α. Panels are representative of three experiments. (C) Western blot analyses of HIF-1α hydroxylated at Pro564 (P564OH) and total HIF-1α in lysates from hypoxia-treated control miRNA or HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells. Panels are representative of six experiments. (D) Control miRNA or HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells were subjected to hypoxia and MG132 (10 uM) treatments. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-HIF-1α antibody and analysed for co-immunoprecipitating proteins by Western blotting using anti-pVHL antibody. Normal rabbit immunoglobulin was used as a specificity control. Input lanes represent 25 % of the total protein. Panels are representative of three experiments. (E) pVHL-deficient RCC4 or wild-type pVHL transfected RCC4 cells were transfected with control vector or expression vector for FLAG (FL)–HEXIM1. The cells were incubated under hypoxia for 8 h as indicated. The expression of HEXIM1, HIF-1α and GAPDH were analysed by Western blot analyses. Panels are representative of four experiments. Molecular masses in kDa are shown next to the Western blots.

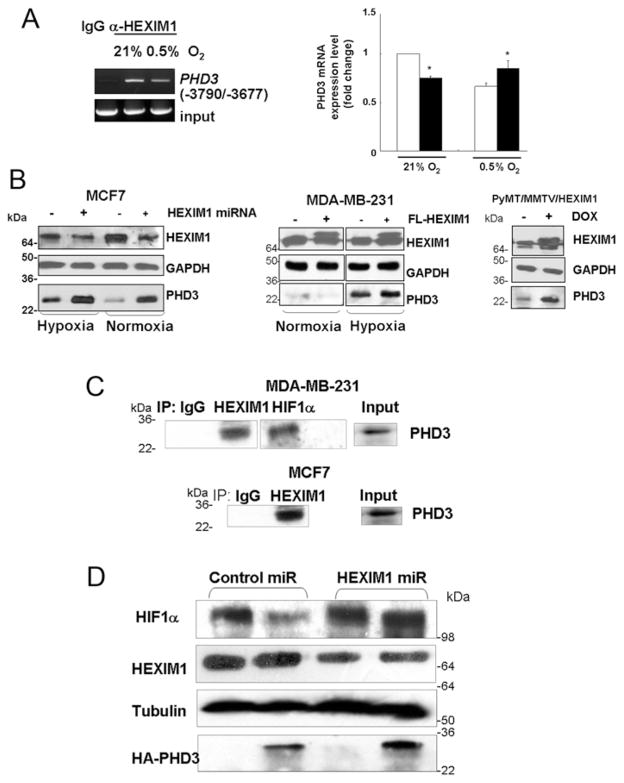

HEXIM1 regulated expression of and interacted with PHD3

To explore the potential basis for HEXIM1 regulation of the hydroxylation of HIF-1α, we examined our microarray dataset [14]. Genes involved in post-translational modifications were shown to be enriched in our pathway analyses of genes differentially expressed in MCF7 control miRNA and MCF7-HEXIM1 miRNA cells (P = 10−5). One of the differentially expressed post-translational modifications genes encodes PHD3, which has been reported to down-regulate HIF-1α protein stability [22,23]. Our ChIP-seq analyses and validation by standard ChIP indicated recruitment of HEXIM1 to the −3790/−3677 region of the PHD3 gene (Figure 3A). A consequence of the recruitment of HEXIM1 to the PHD3 gene was down-regulation of PHD3 expression under normoxia conditions and up-regulation of PHD3 expression in hypoxia-treated MD-MB-231 cells (Figures 3A and 3B). Mechanistically, the opposite effects of HEXIM1 on PHD3 expression during normoxic and hypoxic conditions may be due to the presence of distinct factors in the transcriptional complex with HEXIM1 on the PHD3 gene under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. The HEXIM1-binding site was distinct from the HIF-1α-binding site [24] and suggested HIF-1α independent regulation of PHD3 by HEXIM1. Consistent with the inhibition of PHD3 expression by HEXIM1 under normoxic conditions was the enhancement of PHD3 expression in HEXIM1 miRNA-transfected cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. HEXIM1 up-regulated expression and interaction with PHD3.

(A) Left-hand panel, ChIP analyses of MCF7 cell lysates immunoprecipitated with antibodies against HEXIM1 or control non-specific rabbit immunoglobin, followed by PCR amplification of the −3790/−3677 region of the PHD3 gene. Panels are representative of three experiments. Right-hand panel, PHD3 mRNA levels in control and FLAG (FL)–HEXIM1-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells were quantified and normalized to GAPDH. Panels are representative of three experiments. (B) Representative Western blots indicating regulation of PHD3 by HEXIM1 in hypoxia-treated MCF7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells. Panels are representative of three experiments. Also shown is a representative Western blot of PHD3 expression in tumour lysates from control and doxycycline-treated PyMT/MMTV/HEXIM1 mice. Blots were probed with anti-GAPDH antibody as a loading control. Panels represent five mice per group [±doxycycline (DOX)]. (C) MCF7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to hypoxia treatment (8 h). Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using the antibodies indicated and analysed for co-immunoprecipitating proteins by Western blotting using anti-PHD3 antibody. Normal rabbit immunoglobulin was used as a specificity control. Input lanes represent 25 % of the total protein. Panels are representative of three experiments. (D) Expression of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions in control miRNA and HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells and in the absence or presence of HA-tagged PHD3 were analysed by Western blot analyses. Panels are representative of at least three experiments. Molecular masses in kDa are shown next to the Western blots.

Under hypoxia, PHD3 expression was induced through HIF-1α in certain cells (including breast cells MCF7 and BTB474) [22]. Up-regulation of HIF-1α probably accounted for our finding that down-regulation of HEXIM1 also resulted in up-regulation of PHD3 under hypoxic conditions (Figure 3B). The effect of increased expression of HEXIM1 in the hypoxic environment of advanced breast cancer was also examined.. We have recently reported that re-expression of HEXIM1 through transgene expression inhibited metastasis in a mouse model of metastatic mammary cancer, the PyMT transgenic mouse, that can be correlated with decreased expression of HIF-1α, VEGF, compensatory pro-angiogenic factors and vascularization [14]. HEXIM1 re-expression in this mouse model resulted in increased PHD3 expression (Figure 3B).

We then determined whether HEXIM1 can influence PHD3 regulation of HIF-1α stability. HEXIM1 interacted with PHD3 (Figure 3C), suggesting that HEXIM1 may play a role in the down-regulation of HIF-1α by PHD3 by also promoting an interaction between HIF-1α and PHD3. In support, down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in up-regulation of HIF-1α expression despite the increase in PHD3 (Figure 3D).

The above results suggested that there are two mechanisms by which HEXIM1 regulates PHD3, by direct transcriptional up-regulation of the PHD3 gene or by interaction with PHD3. Both mechanisms are required for HEXIM1 to inhibit HIF-1α via PHD3. Two mechanisms would ensure negative regulation of HIF-1α activity was maintained. Up-regulation by HEXIM1 is especially critical in breast cancer cells where expression of PHDs is decreased [25]. In cases where HEXIM1 expression was also down-regulated, as in metastatic breast cancer [14], the up-regulation of PHD3 was likely owing to up-regulation of HIF-1α. However, at these low levels, HEXIM1 was unable to effectively mediate an interaction between PHD3 and HIF-1α, thus up-regulation of HIF-1α was maintained.

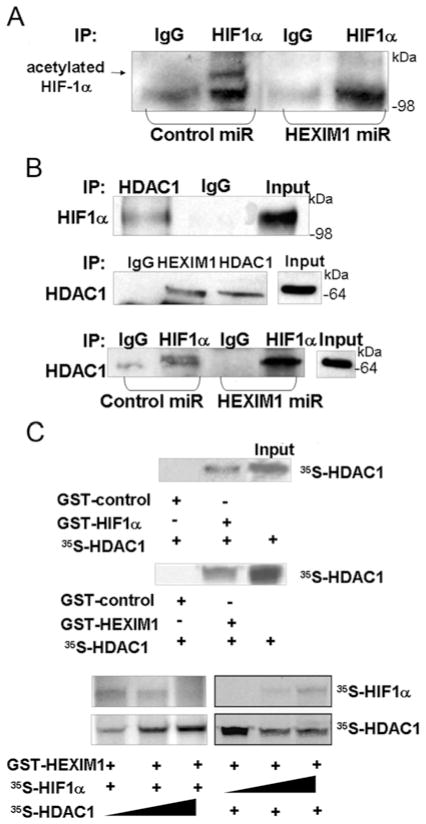

HEXIM1 inhibited HDAC1–HIF-1α interaction and increased HIF-1α acetylation

We tested other potential modes of regulation of HIF-1α by HEXIM1. The acetylation of HIF-1α has been reported to induce interaction of HIF-1α with pVHL and HIF-1α ubiquitination [13]. HDAC1 has been reported to deacetylate HIF-1α and, as such, to be a positive regulator of HIF-1α stability via direct interaction [26]. However, the role of HDAC1 and ARD1, the acetyltransferase that acetylates HIF-1α, in the regulation of HIF-1α is controversial, since both overexpression and silencing of ARD1 were shown to have no impact on HIF-1α stability and on the mRNA levels of the downstream target genes of HIF-1α [27,28].

We observed deacetylation of HIF-1α upon down-regulation of HEXIM1 (Figure 4A). We also observed that HEXIM1 interacted with HDAC1 (as shown by co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, Figure 4B) and GST-pull down assays (Figure 4C). Attenuation of this interaction by down-regulating HEXIM1 resulted in enhanced interaction of HIF-1α with HDAC1 (Figure 4B). Although the enhanced HIF-1α–HDAC1 interaction can be attributed to increased HIF-1α level, the deacetylation of HIF-1α supports the enhanced HIF-1α–HDAC1 interaction. Moreover our GST pull-down assays indicated that the interaction between HEXIM1 and HIF-1α was attenuated in the presence of HDAC1, and the interaction between HEXIM1 and HDAC1 was attenuated in the presence of HIF-1α (Figure 4C). These findings suggested a competition between HEXIM1 and HDAC1 for binding to HIF-1α or that HIF-1α provided a platform for an interaction between HEXIM1 and HDAC1. HEXIM1 then sequestered HDAC1 from the HIF-1α protein complex. Thus HEXIM1 can induce a decrease in HIF-1α protein levels by inhibiting the ability of HDAC1 to act on HIF-1α.

Figure 4. Down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in enhanced HIF-1α–HDAC1 interaction and deacetylation of HIF-1α.

(A) Control and HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells were subjected to hypoxia treatment (8 h). Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-HIF-1α antibody and analysed by Western blotting using the indicated anti-pan-acetyl antibody. Panels are representative of two experiments. (B) MCF7 cells were subjected to hypoxia treatment (8 h). Lysates were immunoprecipitated using the indicated antibodies and analysed for co-immunoprecipitating proteins by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Normal rabbit immunoglobulin was used as a specificity control. Input lanes represent 25 % of the total protein. Panels are representative of three experiments. (C) In vitro translated and indicated [35S]methionine-labelled proteins were incubated with the indicated GST-fusion proteins bound to Sepharose. The Input lane represents 10 % of the total volume of in vitro translated product used in each reaction. Panels are representative of eight experiments. Molecular masses in kDa are shown next to the Western blots.

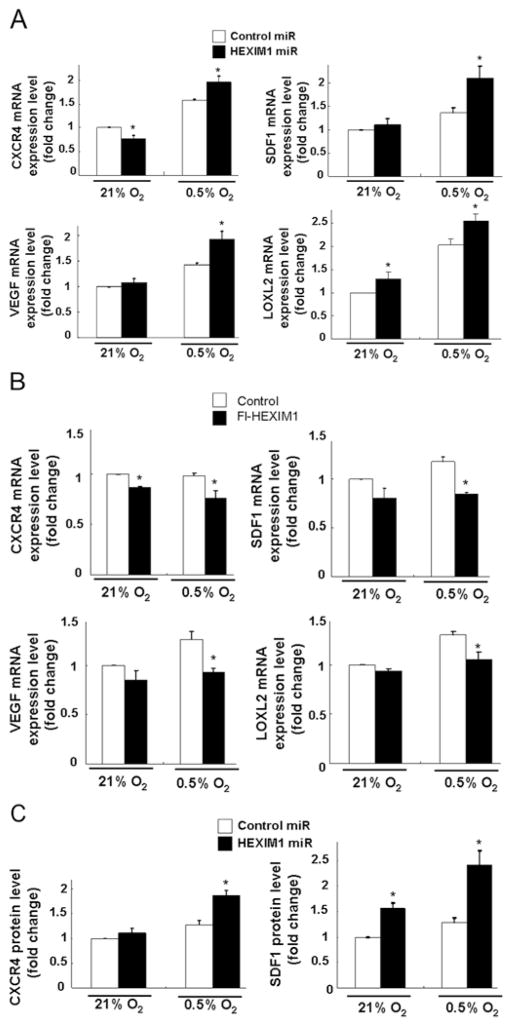

HEXIM1 inhibits the expression of HIF-1α target genes

The down-regulation of HIF-1α protein levels by HEXIM1 prompted us to examine HEXIM1 inhibition of other HIF-1α-regulated genes besides VEGF. HIF-1α promotes metastases of breast cells by up-regulating CXCR4 and SDF1 signalling [29] and both factors are expressed in breast cells [30]. Another transcriptional target, LOXL2 (lysyl oxidase-like 2) [31], is secreted by hypoxic breast tumour cells, accumulates at premetastatic sites, cross-links collagen IV in the basement membrane, and is essential for CD11b± myeloid cell recruitment [32]. Down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in enhanced hypoxia-induced VEGF, SDF-1, CXCR4 and LOXL2 mRNA expression and CXCR4 and SDF1 protein expression in MCF7 cells (Figure 5). We have previously reported on down-regulation of VEGF protein levels by HEXIM1 [16]. HEXIM1 also altered expression of CXCR4, SDF-1 and LOXL2 under normoxia conditions, which suggested regulation by HEXIM1 also involved HIF-1α-independent mechanisms (Figure 5).

Figure 5. HEXIM1-regulated expression of HIF-1α-regulated genes.

Hypoxia-induced changes in VEGF, SDF-1, CXCR4 and LOXL2 mRNA levels in (A) control miRNA and HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells or (B) control and FLAG (Fl)–HEXIM1 transfected MDA-MB-231 cells were quantified and normalized to GAPDH. Panels are representative of three experiments. (C) SDF-1 and CXCR4 protein levels in control miRNA and HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells were quantified and normalized to GAPDH. Histograms show the means±S.E.M. from three experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells with the same treatment (for 8 h). Panels are representative of three experiments.

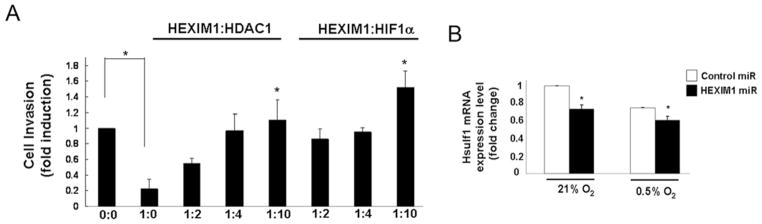

HEXIM1 inhibits hypoxia-induced breast cancer cell invasion

We determined whether HEXIM1 can regulate other known hypoxia-regulated cellular processes through its attenuation of HIF-1α-regulated gene transcription. We have previously observed that HEXIM1 inhibited metastasis using a mouse model of metastatic mammary cancer [14]. Conversely, down-regulation of HEXIM1 in MCF7 cells using HEXIM1 miRNA resulted in enhanced cell invasion [14]. We tested the possibility that inhibition of HIF-1α is a contributing factor in the inhibitory effects of HEXIM1 on cell invasion. Our invasion assays using Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers indicated that HEXIM1 inhibited invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 6A). That HEXIM1 inhibition of HIF-1α is a critical factor in the inhibitory effects of HEXIM1 on breast cancer cell invasion was supported by experiments where cotransfection of HIF-1α or HDAC1 attenuated the inhibitory effects of HEXIM1 on MDA-MB-231 cell invasion.

Figure 6. HEXIM1 inhibited hypoxia-induced invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells.

(A) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with expression vector for HEXIM1 or empty vector, in the absence or presence of increasing levels of expression vectors for HDAC1 or HIF-1α. Cells were then subjected to hypoxia treatment. Invasion of cells through Matrigel was assessed in the transwell invasion assay. *P < 0.05 compared with cells transfected with HEXIM1 expression vector only (i.e. 1:0). Panels are representative of five experiments. (B) Hypoxia-induced changes in HSulf-1 mRNA levels in control miRNA and HEXIM1 miRNA transfected MCF7 cells were quantified and normalized to GAPDH. Graphs are means±S.E.M. from three experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells with the same treatment.

To verify the inhibition of HIF-1α-mediated cell invasion by HEXIM1 we examined inhibition of HSulf-1 expression by HIF-1α. Down-regulation of HSulf-1 expression was shown to mediate hypoxia-mediated enhanced cell migration and invasion [33]. HSulf-1 was also shown to be a direct transcriptional target of HIF-1α. Down-regulation of HEXIM1 resulted in further attenuation of HSulf-1 expression observed under hypoxic conditions (Figure 6B).

DISCUSSION

We have uncovered a novel function of HEXIM1 in directly modulating HIF-1α levels in breast cancer cells. The results from the present study indicate that HIF-1α is a direct target of HEXIM1 and that HEXIM1 regulates post-translational modifications of the HIF-1α protein known to be important for regulating HIF-1α protein stability. HEXIM1 is critical for the ability of PHD3 to down-regulate HIF-1α protein stability under hypoxia conditions. The functional relevance of this regulation is supported by attenuation of the expression of HIF-1α target gene expression and hypoxia-induced cell invasion by HEXIM1. The fact that HIF-1α is a direct target of HEXIM1 and HEXIM1 modulates post-translational modifications of HIF-1α supports the role for HEXIM1 as a critical regulator of HIF-1α activities in breast cancer cells.

PHD3 levels are relatively low across a wide range of normoxic cells, such that PHD2 was the most abundant enzyme in normoxic culture in all cells [22]. However, PHD3 is induced by hypoxia in certain cells (including breast cell lines MCF7 and BTB474) and under these conditions suppression of PHD3 by siRNA increased the half-life of HIF-1α under normoxia and hypoxia [22]. Moreover, there are differences with respect to HIF-1α activation between mice lacking PHD2 and mice lacking pVHL [34], suggesting residual prolyl hydroxylation of HIF-1α by PHD1 or PHD3 in cells lacking PHD2. These results suggest that PHD3 retains significant activity under hypoxic conditions and that the enzyme is important in limiting physiological activation of HIF (particularly HIF-2α) in hypoxia. PHD3 appears to have a lower oxygen Km than PHD2 [23] and therefore may remain active at intermediate levels of hypoxia that can inactivate PHD2. PHD3 is a HIF-1α target up-regulated by HIF-1α, and is proposed to be part of the negative-feedback mechanism [35]. The up-regulation of PHD3 by HEXIM1 suggests HIF-1α-independent regulation by HEXIM1. In breast tumours, PHD3 expression has been correlated with good prognosis [36] and decreased PHD3 expression has been positively correlated with a basal phenotype [37]. Moreover, there is no evidence of methylation-induced epigenetic silencing of PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 in invasive carcinomas as the basis of increased HIF-1α expression [38]. However, PHD1–PHD3 expression did not correlate with HIF-1α expression in breast carcinomas [36]. Moreover, in contrast with the expected down-regulation of HIF-1α activity by PHD3, PHD3 potentiates HIF-1α coactivator function of the pyruvate kinase isoform PKM2 in HeLa cells, resulting in metabolic reprogramming [39]. It is possible that the predominant effects of PHD3 depend on the expression of factors such as HEXIM1 that directs PHD3 to other HEXIM1-interacting factors such as HIF-1α. The opposite effects of HEXIM1 on PHD3 under normoxia and hypoxia may be opportune given the different roles of PHD3 targets, in particular Spry2 that has tumour-suppressor activities and is targeted by PHD3 under normoxic conditions [40]. In doing so, HEXIM1 may prevent some of the growth-promoting effects of PHD3 on cancer cells while inhibiting HIF-1α action. Although the basis for the opposite effects of HEXIM1 on PHD3 expression under normoxia and hypoxia is being further elucidated, the present study supports direct transcriptional regulation of PHD3 by HEXIM1.

HDAC1 deacetylates HIF-1α and is considered to be a positive regulator of HIF-1α stability via direct interaction [26]. However, the role of ARD1, the acetyltransferase that acetylates HIF-1α, in the regulation of HIF-1α is not clear, since both overexpression and silencing of ARD1 were shown to have no impact on the stability and on the mRNA levels of the downstream target genes of HIF-1α [27,28]. It has been proposed that these observations may be due to the expression of MTA1 (metastasis-associated protein 1) [26]. It has been reported that MTA1 is up-regulated under hypoxic conditions in breast cells [26]. MTA1 then interacts with HDAC1, and the HDAC1–MTA1 complex interacts with the ODD domain of HIF-1α. As a result, HIF-1α is deacetylated, thereby blocking the degradation of the protein [26,41]. MTA1 inhibited ARD1-induced HIF-1α degradation, and MTA1 expression levels were closely associated with ARD1 function [26]. In cell lines that express low levels of MTA1, ARD1-induced HIF-1α degradation was significant, whereas ARD1 did not function in other cell lines, such as MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, that express high levels of MTA1 in response to hypoxia. Thus cells with high levels of MTA1 may represent an instance where other modes of regulation of HIF-1α are needed. MTA1-induced deacetylation may counteract PHD3-induced hydroxylation and prevent HIF-1α ubiquitination and degradation. We determined that HEXIM1 is another determining factor in the acetylation of HIF-1α, even in cells that express high levels of MTA1 [26,42], by attenuating the interaction between HEXIM1 and HDAC1. It was recently reported that HDAC1 may be involved in the stabilization of HIF-1α [42]. However, this finding is in contrast with reports that HDAC1 inhibitors attenuate HIF-1α levels and signalling, tumorigenesis and angiogenesis [43–45]. Finally, it is possible that the interaction between HEXIM1 and HDAC1 regulates HIF-1α-mediated transcription through histone deacetylation. However, the enhancement of HIF-1α transcriptional activity has been reported to involve displacement of the histone deacetylases such as HDAC1 from the HIF-1α transcriptional complex [46,47].

HIF-1α is overexpressed in many human cancers and activates transcription of genes involved in crucial features of cancer biology, including angiogenesis, cell survival, glucose metabolism and invasiveness, thus representing an attractive target for a selective cancer therapy [12]. The present study provides new insight into how HIF-1α can be inhibited in breast cancer cells. Inhibition of these factors by HEXIM1 reveals aspects of HEXIM1 mechanism of action not previously identified as it does not rely on HEXIM1 inhibition of the transcriptional elongation machinery. Our studies also support HEXIM1 inhibition of another HIF-1α-regulated cellular processes, cell invasion. Consistent with the proposed role of HSulf-1 in hypoxia-mediated cell invasion, HEXIM1 attenuated HIF-1α inhibition of HSulf-1 expression.

VEGF, SDF-1 and CXCR4 are all HIF-1α target genes that are down-regulated by HEXIM1 and provide a mechanistic basis for our observed effects of HEXIM1 not only on the primary tumour, but also on the tumour microenvironment. We recently reported that HEXIM1 inhibited the recruitment of BMDCs to primary tumours [14]. HEXIM1 inhibition of hypoxia-induced SDF-1 and CXCR4 expression provides a mechanism for HEXIM1 to indirectly act on BMDCs and to suppress metastatic cancer. Intratumoural hypoxia leads to the recruitment of BMDCs, endothelial and pericyte progenitors, tumour-associated macrophages, immature monocytic cells and myeloid cells [48]. Current evidence suggests a promotional role of BMDCs on the existing blood vessels rather than de novo neovascularization in tumours. These cells produce different pro-angiogenic factors and constitute an adaptive mechanism of resistance to angiogenic inhibitors under a low oxygen context. VEGF and SDF-1 are essential in recruiting BM-derived myelomonocytic cells to tumours [49]. BMDCs express the SDF-1 receptor CXCR4 and are recruited to hypoxic tissue by cell tropism to SDF-1 [50].

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Hung Ying Kao for the HDAC1 expression vector and Dr Greg Semenza (Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.) for the HIF-1α expression vector.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number CA92440 (to M.M.M.)] and ACS [grant number 121762-RSG-12-097-01-CCG (to S.M.W.)]

Abbreviations used

- ARD1

arrest-defective protein 1

- BMDC

bone-marrow-derived cell

- CXCR4

CXC chemokine receptor 4

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HA

haemagglutinin

- HSulf-1

endosulfatase 1

- HDAC1

histone deacetylase 1

- HEXIM1

hexamethylene-bis-acetamide-inducible protein-1

- HMBA

hexamethylene-bis-acetamide

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- LOXL2

lysyl oxidase-like 2

- MTA1

metastasis-associated protein 1

- ODD

oxygen-dependent degradation

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase

- pVHL

von Hippel–Lindau protein

- PyMT

Polyoma Middle-T antigen

- RT

reverse transcription

- SDF1

stromal-cell-derived factor 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

I-Ju Yeh designed and performed the experiments, analysed the results, and wrote the paper. Ndiya Ogba performed the experiments and edited the paper prior to submission. Ndiya Ogba and Heather Bensigner performed the experiments. Scott Welford designed some of the experiments, contributed to the discussions and edited the paper prior to submission. Monica Montano designed the experiments, analysed the results and edited the paper prior to submission.

References

- 1.Harris AL. Hypoxia: a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:cm8. doi: 10.1126/stke.4072007cm8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundgren K, Holm C, Landberg G. Hypoxia and breast cancer: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:3233–3247. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dachs GU, Tozer GM. Hypoxia modulated gene expression: angiogenesis, metastasis and therapeutic exploitation. Eur J Cancer. 2000;26:1649–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Cassidy J. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahimi-Horn MC, Chiche J, Pouysségur J. Hypoxia and cancer. J Mol Med. 2007;85:1301–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grépin R, Pagès G. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to tumour anti-angiogenic strategies. J Oncol. 2010;2010:835680. doi: 10.1155/2010/835680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazure NM, Brahimi-Horn MC, Berta MA, Benizri E, Bilton RL, Dayan F, Ginouves A, Berra E, Pouyssegur J. HIF-1: master and commander of the hypoxic world. A pharmacological approach to its regulation by siRNAs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Vascul Pharmacol. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O’Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong JW, Bae MK, Ahn MY, Kim SH, Sohn TK, Bae MH, Yoo MA, Song EJ, Lee KJ, Kim KW. Regulation and destabilization of HIF-1 by ARD1-mediated acetylation. Cell. 2002;111:709–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketchart W, Smith KM, Krupka T, Wittmann BM, Hu Y, Rayman PA, Doughman YQ, Albert JM, Bai X, Finke JH, Xu Y, Exner AA, Montano MM. Inhibition of metastasis by HEXIM1 through effects on cell invasion and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2012;32:3829–3839. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittmann BM, Wang N, Montano MM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of cell growth that is down-regulated by estrogens and decreased in breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5151–5158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogba N, Doughman YQ, Chaplin LJ, Hu Y, Gargesha M, Watanabe M, Montano MM. HEXIM1 modulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and function in breast epithelial cells and mammary gland. Oncogene. 2010;29:3639–3649. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masson N, Willam C, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Independent function of two destruction domains in hypoxia-inducible factor-α chains activated by prolyl hydroxylation. EMBO J. 2001;20:5197–5206. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du W, Wright BM, Li X, Finke J, Rini BI, Zhou M, He H, Lal P, Welford SM. Tumor-derived macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes an autocrine loop that enhances renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:1469–1474. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogba N, Chaplin L, Doughman YQ, Fujinaga K, Montano MM. HEXIM1 regulates E2/ERα-mediated expression of Cyclin D1 in mammary cells via modulation of P-TEFb. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7015–7024. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wittmann BM, Fujinaga K, Deng H, Ogba N, Montano MM. The breast cell growth inhibitor, estrogen down regulated gene 1, modulates a novel functional interaction between estrogen receptor α and transcriptional elongation factor cyclin T1. Oncogene. 2005;24:5576–5588. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montano MM, Ekena K, Delage-Mourroux R, Chang W, Martini P, Katzenellenbogen BS. An estrogen receptor-selective coregulator that potentiates the effectiveness of antiestrogens and represses the activity of estrogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6947–6952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appelhoff RJ, Tian YM, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stiehl DP, Wirthner R, Koditz J, Spielmann P, Camenisch G, Wenger RH. Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase domain proteins compensate for decreased oxygen levels. Evidence for an autoregulatory oxygen-sensing system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23482–23491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen C, Nettleton D, Jiang M, Kim SK, Powell-Coffman JA. Roles of the HIF-1 hypoxia-inducible factor during hypoxia response in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20580–20588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan DA, Kawahara TL, Sutphin PD, Chang HY, Chi JT, Giaccia AJ. Tumor vasculature is regulated by PHD2-mediated angiogenesis and bone marrow-derived cell recruitment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo YG, Kong G, Lee MO. Metastasis-associated protein 1 enhances stability of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α protein by recruiting histone deacetylase 1. EMBO J. 2006;25:1231–1241. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilton R, Mazure N, Trottier E, Hattab M, Dery MA, Richard DE, Pouyssegur J, Brahimi-Horn MC. Arrest-defective-1 protein, an acetyltransferase, does not alter stability of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 and is not induced by hypoxia or HIF. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31132–31140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher TS, Etages SD, Hayes L, Crimin K, Li B. Analysis of ARD1 function in hypoxia response using retroviral RNA interference. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17749–17757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronin PA, Wang JH, Redmond HP. Hypoxia increases the metastatic ability of breast cancer cells via upregulation of CXCR4. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marlow R, Strickland P, Lee JS, Wu X, Pebenito M, Binnewies M, Le EK, Moran A, Macias H, Cardiff RD, et al. SLITs suppress tumor growth in vivo by silencing Sdf1/Cxcr4 within breast epithelium. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7819–7827. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schietke R, Warnecke C, Wacker I, Schodel J, Mole DR, Campean V, Amann K, Goppelt-Struebe M, Behrens J, Eckardt KU, Wiesener MS. The lysyl oxidases LOX and LOXL2 are necessary and sufficient to repress E-cadherin in hypoxia: insights into cellular transformation processes mediated by HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6658–6669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong CC, Gilkes DM, Zhang H, Chen J, Wei H, Chaturvedi P, Fraley SI, Wong CM, Khoo US, Ng IO, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a master regulator of breast cancer metastatic niche formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16369–16374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khurana A, Liu P, Mellone P, Lorenzon L, Vincenzi B, Datta K, Yang B, Linhardt RJ, Lingle W, Chien J, et al. HSulf-1 modulates FGF2- and hypoxia-mediated migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2152–2161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG., Jr Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood. 2008;111:3236–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marxsen JH, Stengel P, Doege K, Heikkinen P, Jokilehto T, Wagner T, Jelkmann W, Jaakkola P, Metzen E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-α-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem J. 2004;381:761–767. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peurala E, Koivunen P, Bloigu R, Haapasaari KM, Jukkola-Vuorinen A. Expressions of individual PHDs associate with good prognostic factors and increased proliferation in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan M, Rayoo M, Takano EA, Fox SB. BRCA1 tumours correlate with a HIF-1α phenotype and have a poor prognosis through modulation of hydroxylase enzyme profile expression. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1168–1174. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang KT, Mikeska T, Dobrovic A, Fox SB. DNA methylation analysis of the HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylase domain genes PHD1, PHD2, PHD3 and the factor inhibiting HIF gene FIH in invasive breast carcinomas. Histopathology. 2010;57:451–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo W, Hu H, Chang R, Zhong J, Knabel M, O’Meally R, Cole RN, Pandey A, Semenza GL. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a PHD3-stimulated coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;145:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson K, Nordquist KA, Gao X, Hicks KC, Zhai B, Gygi SP, Patel TB. Regulation of cellular levels of Sprouty2 protein by prolyl hydroxylase domain and von Hippel-Lindau proteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42027–42036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.303222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo YG, Na TY, Seo HW, Seong JK, Park CK, Shin YK, Lee MO. Hepatitis B virus X protein induces the expression of MTA1 and HDAC1, which enhances hypoxia signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:3405–3413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geng H, Liu Q, Xue C, David LL, Beer TM, Thomas GV, Dai MS, Qian DZ. HIF1α protein stability is increased by acetylation at lysine 709. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35496–35505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellis L, Hammers H, Pili R. Targeting tumor angiogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang FW, Que L, Wu M, Wang ZL, Sun J. Effects of trichostatin A on HIF-1α and VEGF expression in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:193–199. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naldini A, Filippi I, Cini E, Rodriquez M, Carraro F, Taddei M. Downregulation of hypoxia-related responses by novel antitumor histone deacetylase inhibitors in MDAMB231 breast cancer cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:407–413. doi: 10.2174/187152012800228706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bodily JM, Mehta KP, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus E7 enhances hypoxia-inducible factor 1-mediated transcription by inhibiting binding of histone deacetylases. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1187–1195. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato A, Endo T, Abiko S, Ariga H, Matsumoto K. Induction of truncated form of tenascin-X (XB-S) through dissociation of HDAC1 from SP-1/HDAC1 complex in response to hypoxic conditions. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2661–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seagroves TN. The complexity of the HIF-1-dependent hypoxic response in breast cancer presents multiple avenues for therapeutic intervention. In: Lu Y, Mahato RI, editors. Pharmaceutical Perspectives of Cancer Therapeutics. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 521–558. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du R, Lu KV, Petritsch C, Liu P, Ganss R, Passegué E, Song H, Vandenberg S, Johnson RS, Werb Z, Bergers G. HIF1α induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]