Abstract

Purpose

Although members of the galectin family of carbohydrate-binding proteins are thought to play a role in the immune response and regulation of allograft survival, little is known about the galectin expression signature in failed corneal grafts. The goal of this study is to compare the galectin expression pattern in accepted and rejected murine corneal allografts.

Method

Using BALB/c mice as recipients and C57BL/6 mice as donors, a total of 57 transplants were successfully performed. One week after transplantation, the grafts were scored for opacity by slit-lamp microscopy. Opacity scores of 3+ or greater on postoperative week 4 were considered rejected. Grafted corneas were harvested on postoperative week 4, and their galectin expression was analyzed by Western blot and immunofluorescence staining.

Result

As determined by Western blot analyses, galectins-1, -3, -7, -8 and -9 were expressed in normal corneas. Although in both accepted and rejected grafts, expression levels of the five lectins were upregulated compared to normal corneas, there were distinct differences in the expression levels of galectins-8 and -9 between accepted and rejected grafts, as both Western blot and immunofluorescence staining revealed galectin-8 is upregulated, whereas galectin-9 is downregulated in rejected grafts compared to accepted grafts.

Conclusion

Our findings that corneal allograft rejection is associated with an increased galectin-8 expression and a reduced galectin-9 expression, support the hypothesis that galectin-8 may reduce graft survival, whereas galectin-9 may promote graft survival. As a potential therapeutic intervention, inhibition of galectin-8 and/or treatment with exogenous galectin-9 may enhance corneal allograft survival rates.

Keywords: galectin, corneal allografts, inflammation, neovascularization

INTRODUCTION

Corneal transplantation is the most common form of solid organ transplantation, comprising over 40,000 surgical procedures annually in the United States alone.1 Due to the immune privilege and avascularity of normal corneas, corneal allograft survival rates are commonly as high as 90%.2 However, pre-operative risk factors such as corneal vascularization, ocular surface disease or multiple prior graft failure can markedly increases the rejection rate to 50−90%.3,4 The mechanism of corneal allograft rejection involves both innate and adaptive immunity, and it comprises three steps as: (i) antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells and macrophages migrate to draining lymph nodes via lymphatic vessels, (ii) APCs prime the T cells in the lymph nodes and the activated T cells undergo clonal expansion, and (iii) activated T cells enter the bloodstream and return to the cornea to attack allografts (reviewed in Niederkorn5 and Skobe).6 Strategies to block one or more of these three steps can increase the survival rate of the corneal allografts.

Galectins are a family of animal lectins capable of recognizing β-galactosides.7,8 Galectins are important modulators of immune response as cells of the innate and adaptive immune system both express galectins9 and as these galectins can be either anti- or pro-inflammatory.10,11 In general, both galectins-1 and -9 are considered anti-inflammatory galectins, whereas galectin-3 is viewed as a pro-inflammatory galectin. Functions of neutrophils and macrophages are inhibited by galectins-1 and -9, but are promoted by galectin-3. Both galectin-1 and -9 treatment promotes regulatory T (Treg) cell polarization, whereas galectin-3 plays a negative role in Treg cell expansion (reviewed in Liu et al and Rabinovich et al).11,12 More recently, galectins have been shown to modulate angiogenic responses as galectins-1, -3, and -8 are pro-angiogenic,13-15 whereas galectin-9 is anti-angiogenic.16

Recent studies demonstrate the critical importance of several members of galectin family for graft survival. Non-ocular studies have shown that: (i) galectin-1 has anti-inflammatory effects and promotes immunological tolerance of renal allografts in rats and liver allografts in mice17,18 and (ii) galectin-9 promotes immunosuppressive environment and prolongs survival of liver allografts in rats, and cardiac and skin allografts in mice.19-22 In addition, the expression level of galectin-7 is markedly elevated in renal allografts undergoing acute rejection episodes.23 Thus far, only one report demonstrates involvement of galectins in the survival of corneal allografts, as graft survival in mice treated with an anti-galectin-9 neutralizing antibody is significantly reduced and as Tim-3–galectin-9 interactions assist to establish the immune privilege of these grafts.24 However, other than galectin-9, virtually nothing is known about the role of galectins in corneal allografts.

Despite such major interest in the functions of galectins, their expression pattern in the context of corneal transplantation has thus far not been elucidated. Here we seek to compare the expression levels and distribution of galectins in mouse corneas with accepted and rejected allografts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Specific reagents included: Odyssey® blocking buffer (OBB) from Li-Cor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE); goat anti-mouse galectin-1 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); a hybridoma secreting rat anti-human/mouse galectin-3 (mAb M3/38) from ATCC (Manassas, VA); rabbit anti-mouse galectin-7 from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX); rabbit anti-human/mouse galectin-8 from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); rat anti-mouse galectin-9 (clone 108A2) from BioLegend (San Diego, CA); anti-β-actin (clone AC-15) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Infrared secondary antibodies obtained from Li-Cor were: donkey anti-goat IgG IRDye 800CW, donkey anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 680LT, goat anti-rat IgG IRDye 800CW, goat anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 680LT, and goat anti-mouse IgG IRDye 680LT. Fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies purchased from Life technologies (Grand Island, NY) were: Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-rat IgG, Alexa Fluor 568®-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 488®-conjugated anti-goat IgG.

Animal

BALB/c (male, 8 to 10 weeks old) and C57BL/6 (male, 6 weeks old) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experimental procedures were conducted in compliance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statements for the use of animals in ophthalmic and visual research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tufts University.

Corneal transplantation

BALB/c mice were used as graft recipients and C57BL/6 mice were used as donors. For preparation of donor corneas, mice were anesthetized by intramuscular injections with ketamine (125 mg/kg) and xylazine (8.5mg/kg). To prevent iris damage, pupils were preoperatively dilated with tropicamide ophthalmic solution (1%, Akorn, Lake Forest, IL). Tetracaine ophthalmic solution (0.5%, Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) was used as topical anesthetic. The donor corneas were marked with a 2.0 mm trephine, excised with Vannas scissors, and placed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH7.4). Viscoelastic (Provisc, Alcon Laboratories) was utilized intracamerally to protect the donor corneal endothelium as the donor corneal discs were sutured into similarly prepared 1.5 mm diameter corneal beds of BALB/c mice recipients with 8 to 10 interrupted sutures (11-0 nylon, Surgical Specialties, Reading, PA). At the conclusion of surgery, the viscoelastic material was exchanged for PBS, Neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and Bacitracin Zinc ophthalmic Ointment USP (Akorn) were topically applied, and a single eyelid suture (8-0 nylon, Surgical Specialties) was performed. Both eyelid and cornea sutures were removed one week of surgery. All mice were sacrificed on postoperative week 4, and the enucleated eyes were used for Western blot analyses and immunofluorescence staining.

Procedures involving syngeneic graft controls (n=11) were the same except that donor corneas from BALB/c mice were used.

Evaluation and scoring of mouse corneal allografts

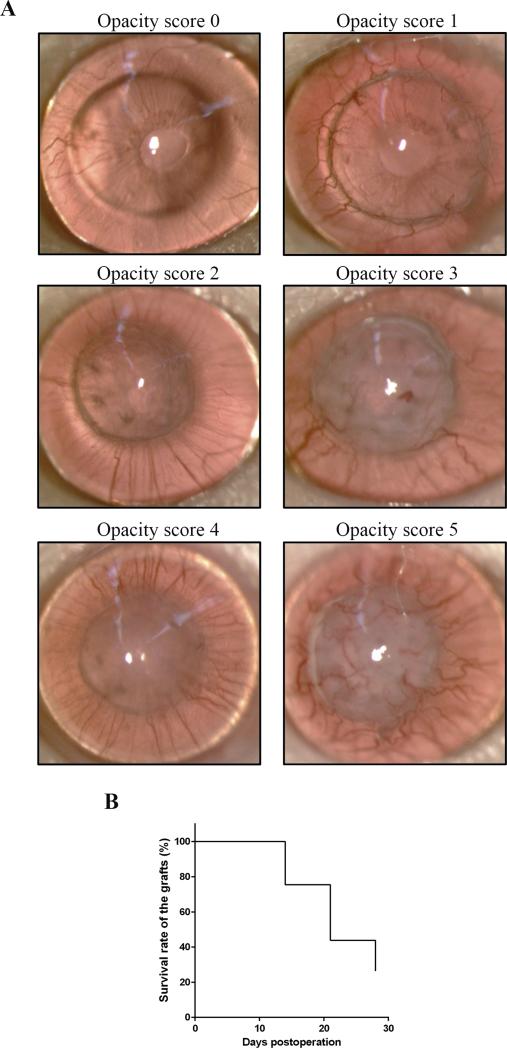

Grafts were evaluated for signs of rejection by slit-lamp biomicroscopy (SL-D7, Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) once per week for 4 weeks by a single observer. A previously reported scoring system25 was used to grade the degree of corneal clarity, ranging from 0 to 5+ (0, clear graft; 1+, minimal superficial opacity; 2+, mild stromal opacity with pupil margin and iris vessels visible; 3+, moderate stromal opacity with only pupil visible; 4+, intense stromal opacity with the anterior chamber visible; 5+, severe stromal opacity with total obscuration of the anterior chamber). Grafts with an opacity score of 3+ or greater on postoperative week 4 were considered rejected; grafts with opacity scores of 3+ or greater on postoperative week 2 which never cleared were also considered rejected.

Selection of galectins

In a recent study (Chen et al, submitted), we have established that of the 15 known galectins, only five, galectins-1, -3, -7, -8 and -9, are relevant to corneal diseases. Therefore, for the current study, the specific expression pattern of these five galectins were examined.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein extracts of mouse corneas were prepared in a radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete tablets, Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) and 2% SDS. Four or more corneas from the accepted or the rejected group were pooled and considered one biological replica. Aliquots of lysates containing 30 μg of proteins were subjected to electrophoresis in 4-15% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, and CA). Protein blots of the gels were blocked with OBB and incubated with goat anti-galectin-1 (1:1,000) and rabbit anti-galectin-8 (1:750) primary antibodies in OBB (overnight, 4°C). The secondary antibodies used were anti-goat IgG 800CW and anti-rabbit IgG 680LT diluted in OBB (1:10,000, 45 min, 25°C). Blots were then scanned with the Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System using Image Studio v2.0 software (Li-COR). After image acquisition, the blots were stripped using the NewBlot nitrocellulose stripping buffer (Li-COR) and re-probed using rabbit anti-galectin-7 (1:10,000) and rat anti-galectin-9 (1:1,000) as primary antibodies. The secondary antibodies used were anti-rat IgG 800CW and anti-rabbit IgG 680LT. After image acquisition, the blots were stripped again and reprobed with rat anti-galectin-3 (1:5,000) and mouse anti-β-actin (1:10,000) as primary antibodies, and anti-rat IgG 800CW and anti-mouse IgG 680LT as secondary antibodies. Relative band intensity was quantified by Image Studio v2.0 software. For total corneal extracts, data were normalized to β-actin expression. We have previously tested each anti-galectin antibody used in the current study for specificity against recombinant human galectins-1, -3, -7, -8 and -9 by Western blot analysis (Chen et al, submitted) and have shown that the antibodies against galectins-1, -3, -7 and -8 do not cross-react with any other galectins examined. According to the product data sheet, the anti-mouse galectin-9 antibody does not cross-react to human galectin-9.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Frozen sections of the eyes were fixed with iced acetone (10 min, 25° C), blocked with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (30 min, 25° C, Life Technologies), and immunostained using anti-galectin primary antibodies (1:100 dilution in 5% BSA/PBS, overnight, 4°C), as described in the previous section for Western blot analyses, and Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-rat, Alexa Fluor 568®-conjugated anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488®-conjugated anti-goat secondary antibodies (1:300 dilution in 5% BSA/PBS, 1 hr, 25°C). Negative controls with no applied primary antibody were also used. Fluorescence images were acquired by Leica TCS SPE imaging system (Leica).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t test in Prism 6 (GraphPad). P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Graft survival rate of corneal allografts

Normal risk corneal transplantation (graft donors: C57BL/6 mice; graft recipients: BALB/c mice) was successfully performed in 57 eyes, defined as opacity score 0 on postoperative week 1. Grafts on postoperative week 2 with corneal opacity scores of 3 or more which never cleared were considered rejected; grafts on postoperative week 4 with corneal opacity scores of 3 or more were also considered rejected. Representative photographs of rejected (opacity score 5) and accepted (opacity score 1) allografts on postoperative week 4 are shown in Figure 1A. Graft survival rate was 75% (43/57) on postoperative week 2, 44% (25/57) on postoperative week 3, and 26% (15/57) on postoperative week 4 (Fig. 1B). Survival rate of syngeneic grafts was 100% on postoperative week 4 (N=11, data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

(A) BALB/c mice (N=57) were transplanted with corneal grafts from C57BL/6 mice. Representative slitlamp photomicrographs of allografts with opacity scores 0 to 5 on postoperative week 4 are shown. The scoring system is described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve demonstrates allograft survival rate of 26% on postoperative week 4.

Expression pattern of galectins in accepted and rejected corneal allografts

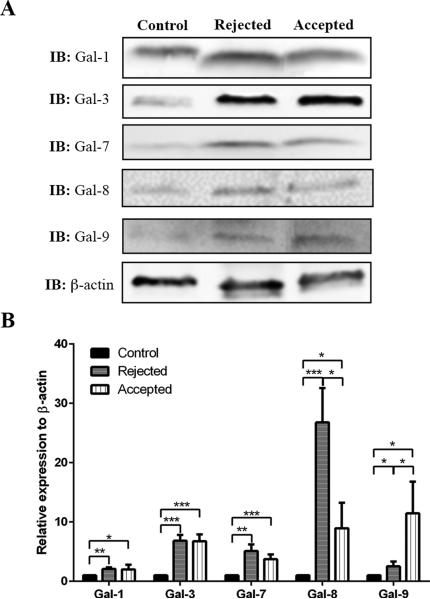

On postoperative week 4, accepted and rejected corneal allografts were collected and analyzed separately. As a control, corneal discs marked with a 2 mm trephine and excised from normal C57BL/6 mice were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with corneas from normal BALB/c mice without the central corneal regions. Fold-change values relative to β-actin expression of various galectins are shown in Fig. 2. Expression levels of all five galectins in both rejected and accepted corneal allografts were significantly increased compared to controls. There were distinct differences in the expression levels of galectins-8 and -9 between accepted and rejected grafts, as galectin-8 expression level in rejected corneal allografts was markedly higher (26.8-fold) than in accepted (9.0-fold) corneal allografts (Fig. 2). Conversely, galectin-9 expression level in rejected corneal allografts was substantially lower (2.5-fold) compared to the accepted (11.5-fold) corneal allografts (Fig. 2). Expression levels of galectins-1, -3 and -7 exhibited no significant differences between rejected and accepted corneal allografts (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Detection of galectins expression by Western blotting in normal corneas and in corneas with rejected and accepted allografts. Lysates of whole corneas containing 30 μg of protein were subjected to electrophoresis in 4-15% SDS-PAGE gels. Protein blots of the gels were probed using anti-galectin antibodies as descried in Methods. A. Representative immunoblots. B. Relative band intensity was quantified by ImageStudio. Expression value of each galectin was normalized to β-actin. A value of 1.0 was given to the expression of each galectin in the normal cornea, and the expression values of galectins in the rejected and accepted allografts were calculated as fold changes with respect to the control cornea. Four or more corneas were pooled and considered one biological replica. N=4. Data are plotted as Mean ± SEM and analyzed using Student's t test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Immunofluorescence localization of galectins in accepted and rejected corneal allografts

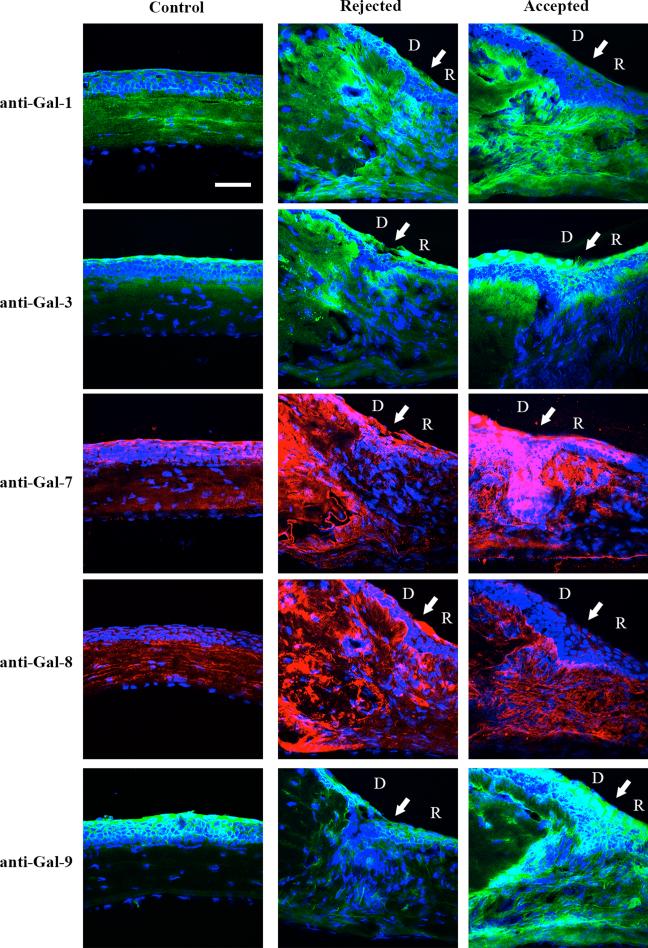

To investigate galectin expression pattern at the tissue level, frozen sections from normal corneas and corneas with accepted and rejected allografts on postoperative week 4 (N=3 each) were immunostained with anti-galectin antibodies. In normal corneas, galectin-1 was mainly expressed in corneal stroma; galectin-3 was mainly expressed in corneal epithelium, and galectins-7, -8 and -9 were expressed in both corneal stroma and epithelium (Fig. 3). Galectin-9 immunoreactivity in the normal corneal stroma was visible but at a much reduced intensity compared to that in the normal epithelium. In both rejected and accepted allografts, immunoreactivity of all five lectins was stronger compared to control. In addition, consistent with the results of the Western blot analysis, compared to the accepted grafts, there was increased galectin-8 immunoreactivity and decreased galectin-9 immunoreactivity in the rejected grafts. Also, similar results were obtained when the tissue sections were stained with an immunoperoxidase-based chromogenic detection system (data not shown). In addition, galectin-3 immunoreactivity in donor stroma was stronger in rejected grafts, whereas galectin-9 immunoreactivity in recipient stroma was stronger in accepted grafts (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Immunofluorescence localization of galectins in normal corneas and corneas with rejected and accepted allografts. Frozen tissue sections were immunostained using antibodies against galectins-1, -3, -7, -8, and -9, and Alexa fluor 488-conjugated anti-goat (for galectin-1, green), Alexa fluor 488-conjugated anti-rat (for galectins-3 and -9, green) and Alexa fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit (for galectins-7 and -8, red), followed by counterstaining with DAPI (blue). White arrows indicate the interface between donor (D) and recipient (R). Immunostaining processing and exposure time of images in rejected and accepted allografts were the same. Note that in normal corneas, galectin-1 is expressed mainly in corneal stroma, galectin-3 is expressed mainly in corneal epithelium, and galectins-7, -8 and -9 are present in both epithelium and stroma. In both rejected and accepted allografts, immunoreactivity of the five lectins is detected in both corneal epithelium and stroma. No immunoreactivity was detected in control corneas which were treated the same way as the experimental group except that isotype control IgG was used as primary antibody or the step involving incubation with the primary antibody was omitted (negative control, data not shown). N=3 for each galectin. Bar = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that rejected corneal allografts have a higher galectin-8 and a lower galectin-9 protein expression compared to accepted corneal allografts. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the galectin expression signature of mouse corneal allografts.

It has been reported that galectin-9 plays an immunosuppressive role in corneal allografts.24 Consistent with this notion, we observed that galectin-9 expression is higher in the accepted corneal allografts than in the rejected corneal allografts. The upregulation of galectin-9 may dampen inflammation in the corneal allografts by promoting Treg cell polarization26 and impairing the functions of natural killer cells,27 which are also involved in corneal allograft rejection.28 Notably, in control corneas, galectin-9 is mainly expressed in the epithelium. It has been reported that although corneal epithelium express over 90% of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, removal of corneal epithelium does not enhance corneal graft survival in humans and even appears to exacerbate corneal allograft rejection in mice,29-31 suggesting the corneal epithelium suppresses inflammation and neovascularization in corneal allografts. In fact, recent studies have shown that nonvascular VEGFR-3 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3) and alternatively spliced VEGF receptor variants including soluble VEGFR-1, R-2 and R-3 expressed in corneal epithelium are key in maintaining the angiogenic and/or immune privilege status of the cornea.32-35 The molecular mechanism by which galectin-9 exerts its anti-inflammatory function in corneal epithelium is still unclear. Further investigation using mice with corneal epithelium-specific deficiency of galectin-9 may establish its role in corneal allograft survival. Regardless, our findings that galectin-9 expression is reduced in rejected grafts, and previous studies showing that galectin-9 is anti-inflammatory (reviewed in Wiersma et al)36 and that anti-galectin-9 antibody treatment reduces corneal allograft survival,24 are consistent with the suggestion that exogenous galectin-9 treatment may be expected to promote corneal allograft survival.

Interestingly, there was no difference in the expression of galectin-1, another anti-inflammatory galectin and galectin-3, a pro-inflammatory galectin, between the accepted and rejected corneal allografts. However, compared to the normal corneas, the expression of galectins-1 and -3 was higher in both accepted as well as rejected grafts, possibly suggesting that these two lectins may be upregulated in response to the trauma of the surgical procedure. Considering that exogenous galectin-1 inhibits acute and chronic inflammation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated corneal infection,37 in herpes simplex virus-mediated corneal infection38 and in experimental colitis39 and that galectin-1 promotes Treg cell polarization, it is reasonable to propose that exogenous galectin-1 treatment may also prolong corneal allograft survival. On the other hand, given that galectin-3 deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis,40 which is considered a chronic inflammatory disease,41 and that higher frequency of Treg cells is observed in galectin-3 knockout mice,42 it seems likely that inhibiting galectin-3 may increase corneal allograft survival.

The role of galectins-7 and -8 in immunity has thus far not been well-characterized. On one hand, galectin-8 promotes apoptosis of activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which may interfere with T cell expansion.43 On the other hand, galectin-8 promotes proliferation and co-stimulation of naïve T cell, which may promote inflammation.43 To identify the role of galectin-8 in the context of corneal immunity and allograft survival, it will be important to investigate the effect of galectin-8 on different T cell sub-populations including Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cells. Nevertheless, our finding that galectin-8 expression is higher in the rejected allografts than in the accepted allografts suggests that galectin-8 may promote inflammation and hence rejection. As galectin-8 stimulates endothelial cells to produce several inflammatory cytokines including CXCL1, CXCL3, GM-CSF, IL-6, RANTES and MCP1,44 it can be hypothesized that galectin-8 acts on endothelial cells of the newly-grown vessels, but not directly on immune cells, to promote inflammation in corneal allografts.

As previously noted, immune cells exit corneas towards draining lymph nodes via lymphatic vessels and enter corneal allografts via blood vessels. Blocking angiogenesis and/or lymphangiogenesis have been proven to increase corneal allograft survival rates (reviewed in Skobe et al).6 Recent studies demonstrate that galectins-1 and -3 promotes angiogenesis through modulating the functions of some key angiogenic molecules including VEGFR-2 and integrins, and that galectin-8 provokes angiogenesis through CD166 and, more likely, integrins (reviewed in Thijssen et al).45 Conversely, galectin-9 reduces angiogenesis in the chick chorioallantoic membrane assay,16 and exogenous galectin-9 treatment decreases herpes simplex virus-induced corneal angiogenesis.46 Although the interaction between galectin-9 and Tim-3 is involved in resolving herpes simplex virus-induced corneal pathology including angiogenesis, Tim-3 is not reported to be expressed in endothelial cells. Therefore, the molecules which bind galectin-9 in endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis are yet to be identified.

In conclusion, our findings of higher galectin-8 expression and lower galectin-9 expression in rejected corneal allografts as well as published studies demonstrating the roles of galectin-8 in promoting angiogenesis and of galectin-9 in inhibiting angiogenesis and promoting Treg cell polarization, lead us to propose that treatment with exogenous recombinant galectin-9 and/or inhibiting galectin-8 with siRNA or blocking antibody via subconjunctival injections may prolong corneal allograft survival. In addition, considering the known capability of galectins-1 and -3 in suppressing and promoting inflammation, respectively, and despite our equivocal findings in this regards, it remains possible that treatment with exogenous galectin-1 and/or inhibition of galectin-3 might also promote corneal allograft survival. Hopefully such studies will provide impetus for in-depth investigation of the actions of galectins in corneal allograft immunology as well as their potential clinical implications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deshea Harris (Schepens Eye Research Institute) for administrative assistance.

Grant information: This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grants R01EY007088 (NP), R01EY009349 (NP), R01EY022695 (PH), Mass Lions Eye Research fund (NP), New England Corneal Transplant Fund (NP), an unrestricted award from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Tufts University, Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PH), and Japan Eye bank (SS).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tan DT, Dart JK, Holland EJ, et al. Corneal transplantation. Lancet. 2012;379:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldock A, Cook SD. Corneal transplantation: how successful are we? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:813–815. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann B, Taylor RS, Cursiefen C. Corneal neovascularization as a risk factor for graft failure and rejection after keratoplasty: an evidence-based meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1300–1305. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fink N, Stark WJ, Maguire MG, et al. Effectiveness of histocompatibility matching in high-risk corneal transplantation: a summary of results from the Collaborative Corneal Transplantation Studies. Cesk Oftalmol. 1994;50:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederkorn JY, Larkin DF. Immune privilege of corneal allografts. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:162–171. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.486100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skobe M, Dana R. Blocking the path of lymphatic vessels. Nat Med. 2009;15:993–994. doi: 10.1038/nm0909-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DN. Galectinomics: finding themes in complexity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:209–231. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins as modulators of tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:29–41. doi: 10.1038/nrc1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasta GR. Roles of galectins in infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:424–438. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu FT. Galectins: a new family of regulators of inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2000;97:79–88. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinovich GA, Toscano MA. Turning 'sweet' on immunity: galectin-glycan interactions in immune tolerance and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:338–352. doi: 10.1038/nri2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins: regulators of acute and chronic inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1183:158–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thijssen VL, Postel R, Brandwijk RJ, et al. Galectin-1 is essential in tumor angiogenesis and is a target for antiangiogenesis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15975–15980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603883103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markowska AI, Liu FT, Panjwani N. Galectin-3 is an important mediator of VEGF- and bFGF-mediated angiogenic response. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1981–1993. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado VM, Nugnes LG, Colombo LL, et al. Modulation of endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis: a novel function for the “tandem-repeat” lectin galectin-8. Faseb J. 2011;25:242–254. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heusschen R, Schulkens IA, van Beijnum J, et al. Endothelial LGALS9 splice variant expression in endothelial cell biology and angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Yan S, Jiang G, et al. Galectin-1 prolongs survival of mouse liver allografts from Flt3L-pretreated donors. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:569–579. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G, Tu W, Xu C. Immunological tolerance induced by galectin-1 in rat allogeneic renal transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YM, Chen Y, Li JZ, et al. Up-regulation of Galectin-9 in vivo results in immunosuppressive effects and prolongs survival of liver allograft in rats. Immunol Lett. 2014;162:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, He W, Yuan J, et al. Activation of Tim-3-Galectin-9 pathway improves survival of fully allogeneic skin grafts. Transpl Immunol. 2008;19:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, He W, Zhou H, et al. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates CD8+ alloreactive T cell and prolongs survival of skin graft. Cell Immunol. 2007;250:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He W, Fang Z, Wang F, et al. Galectin-9 significantly prolongs the survival of fully mismatched cardiac allografts in mice. Transplantation. 2009;88:782–790. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b47f25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo Z, Ji Y, Zhou H, et al. Galectin-7 in cardiac allografts in mice: increased expression compared with isografts and localization in infiltrating lymphocytes and vascular endothelial cells. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:630–634. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimmura-Tomita M, Wang M, Taniguchi H, et al. Galectin-9-mediated protection from allo-specific T cells as a mechanism of immune privilege of corneal allografts. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano Y, Ksander BR, Streilein JW, Minor H. rather than MHC, alloantigens offer the greater barrier to successful orthotopic corneal transplantation in mice. Transpl Immunol. 1996;4:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(96)80035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seki M, Oomizu S, Sakata KM, et al. Galectin-9 suppresses the generation of Th17, promotes the induction of regulatory T cells, and regulates experimental autoimmune arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golden-Mason L, McMahan RH, Strong M, et al. Galectin-9 functionally impairs natural killer cells in humans and mice. J Virol. 2013;87:4835–4845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01085-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartzkopff J, Schlereth SL, Berger M, et al. NK cell depletion delays corneal allograft rejection in baby rats. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1928–1935. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streilein JW. New thoughts on the immunology of corneal transplantation. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:943–948. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stulting RD, Waring GO, 3rd, Bridges WZ, et al. Effect of donor epithelium on corneal transplant survival. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:803–812. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori J, Streilein JW. Role of recipient epithelium in promoting survival of orthotopic corneal allografts in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:720–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Saint-Geniez M, et al. Nonvascular VEGF receptor 3 expression by corneal epithelium maintains avascularity and vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambati BK, Nozaki M, Singh N, et al. Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1. Nature. 2006;443:993–997. doi: 10.1038/nature05249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, et al. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat Med. 2009;15:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh N, Tiem M, Watkins R, et al. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 is essential for corneal alymphaticity. Blood. 2013;121:4242–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-453043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiersma VR, de Bruyn M, Helfrich W, et al. Therapeutic potential of Galectin-9 in human disease. Med Res Rev. 2013;33(Suppl 1):E102–126. doi: 10.1002/med.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suryawanshi A, Cao Z, Thitiprasert T, et al. Galectin-1-mediated suppression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced corneal immunopathology. J Immunol. 2013;190:6397–6409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajasagi NK, Suryawanshi A, Sehrawat S, et al. Galectin-1 reduces the severity of herpes simplex virus-induced ocular immunopathological lesions. J Immunol. 2012;188:4631–4643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santucci L, Fiorucci S, Rubinstein N, et al. Galectin-1 suppresses experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1381–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKinnon AC, Liu X, Hadoke PW, et al. Inhibition of galectin-3 reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Glycobiology. 2013;23:654–663. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fermino ML, Dias FC, Lopes CD, et al. Galectin-3 negatively regulates the frequency and function of CD4(+) CD25(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells and influences the course of Leishmania major infection. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1806–1817. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tribulatti MV, Cattaneo V, Hellman U, et al. Galectin-8 provides costimulatory and proliferative signals to T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:371–380. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cattaneo V, Tribulatti MV, Carabelli J, et al. Galectin-8 elicits pro-inflammatory activities in the endothelium. Glycobiology. 2014;24:966–973. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thijssen VL, Rabinovich GA, Griffioen AW. Vascular galectins: regulators of tumor progression and targets for cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sehrawat S, Suryawanshi A, Hirashima M, et al. Role of Tim-3/galectin-9 inhibitory interaction in viral-induced immunopathology: shifting the balance toward regulators. J Immunol. 2009;182:3191–3201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]