Abstract

Evidence of social and behavioral problems preceding the onset of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses is consistent with a neurodevelopmental model of these disorders. Here we predict that individuals with a first episode of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses will evidence one of three patterns of premorbid adjustment: an early deficit, a deteriorating pattern, or adequate or good social adjustment. Participants were 164 (38% female; 31% black) individuals ages 15–50 with a first episode of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Premorbid adjustment was assessed using the Cannon-Spoor Premorbid Adjustment Scale. We compared the fit of a series of growth mixture models to examine premorbid adjustment trajectories, and found the following 3-class model provided the best fit with: a “stable-poor” adjustment class (54%), a “stable-good” adjustment class (39%), and a “deteriorating” adjustment class (7%). Relative to the “stable-good” class, the “stable-poor” class experienced worse negative symptoms at 1-year follow-up, particularly in the social amotivation domain. This represents the first known growth mixture modeling study to examine premorbid functioning patterns in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Given that the stable-poor adjustment pattern was most prevalent, detection of social and academic maladjustment as early as childhood may help identify people at increased risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, potentially increasing feasibility of early interventions.

Keywords: premorbid adjustment, social amotivation, first-episode schizophrenia (FEP), psychosis, schizophrenia-spectrum

1.) Introduction

Social, cognitive, and behavioral functioning problems are common among individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum psychotic disorders, during the premorbid phase, after the onset of the prodrome, and comorbid with subsequent clinical symptoms. Premorbid dysfunction in childhood and adolescence could contribute to later impairment during illness by derailing learning necessary for social, educational, and occupational skills (Meehl, 1989). Early detection of deficits may improve public health by identifying people at heightened risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, thereby increasing the feasibility of preventative early interventions and minimizing symptom severity in vulnerable individuals. However, because schizophrenia-spectrum psychotic disorders may represent a heterogeneous set of disorders with multiple etiologies and/or pathologies, early identification has proven complex.

Based on a model proposed and presented by the senior author (Haas and Sweeney, 1992), we postulate that poor premorbid functioning may reflect disruption during critical phases of central nervous system development believed to contribute to schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. For example, neurodevelopmental disruptions during the perinatal and early childhood phases (a “first hit”) may include reduced synaptic plasticity, hippocampal dysgenesis and/or disruption of white matter integrity (Niendam et al., 2009); disruptions during the pubertal phase (a “second hit”) may involve aberrant synaptic pruning, grey and white matter volume reductions, and functional dysconnectivity (Spear, 2000; Mechelli et al., 2011). Thus, disrupted premorbid social maturation and functioning--starting either in the childhood phase or in the adolescent phase, i.e., after the onset of puberty--may indicate abnormal neurodevelopmental processes. Differential patterns of premorbid adjustment and deviations along the course of premorbid development may represent not only the impact of biological changes, but also of social factors. For example, a person with a trajectory of early social maladjustment may have reduced opportunities for learning social skills, which could reinforce poor social functioning at later developmental stages. Examining different trajectories of premorbid functioning may have implications for the clinical staging model of psychosis (e.g., McGorry, 2007), a model which highlights the need to distinguish different developmental stages of psychosis with the goals of 1) identifying where an individual exists on that continuum and 2) providing tailored interventions to address functional and clinical impairments at a given stage.

A number of published studies have found associations between poor and/or deteriorating premorbid functioning and clinical and functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, including worse social functioning, longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), increased negative symptoms, greater cognitive impairment, and poorer quality of life (e.g., Haas and Sweeney, 1992; Larsen, McGlashan, Johannessen, and Vibe-Hansen, 1996; Addington, van Mastrigt, and Addington, 2003; Strous et al., 2004; Haim et al., 2006). Despite converging research suggesting that a subset of people with schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses have especially poor premorbid functioning, findings are less clear in regards to the number and types of premorbid trajectory patterns across developmental periods, with some studies proposing two patterns (poor or intact functioning across development; Farmer et al., 1983; Sham et al., 1996; Corcoran et al., 2003), and other studies finding three (Haas and Sweeney, 1992) or four (Dickey, Haas, Keshavan and Sweeney, 1998; Addington, van Mastrigt, and Addington, 2003) patterns.

In our own previous study (Haas and Sweeney, 1992) we found that total scores on the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS; Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982) differentiated 3 subtypes of patients with first-episode schizophrenia—one with consistent mild-moderate dysfunction, one with stable-poor dysfunction, one with an initially intact premorbid functioning that deteriorated progressively—which capture the variation in onset of poor functioning predicted by a first and second “hit” to neurodevelopmental processes. A recent study by Cole and colleagues (2012) replicated these three patterns, examining premorbid adjustment of patients with schizophrenia using latent class growth models, however, in that study an initially poor functioning group in childhood decompensated further across development (i.e., “a poor-worsening” group rather that a “stable-poor” group). Thus, the literature on premorbid trajectories suggests that some people with schizophrenia exhibit functional deficits prior to puberty, others after, while others do not exhibit notable behavior changes prior to the onset of the prodrome. Such variance in premorbid patterns of dysfunction is possibly due to heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disruptions in developmentally divergent groups of affected individuals.

Furthermore, several studies--all using the PAS--distinguish between the domains of academic and social premorbid functioning, and find a number of differences between the domains in terms of both their developmental trajectories and associations with clinical and cognitive variables (e.g., Mukherjee et al., 1991; van Kammen et al, 1994; Cannon et al., 1997; Allen et al., 2001; Larsen et al., 2004). In terms of clinical correlates, poor premorbid social functioning has been specifically associated with symptom-related variables, particularly acute and persistent negative symptoms, and longer duration of untreated psychosis (Allen et al., 2001; McClellan et al, 2003; Larsen et al., 2004; Jeppesen et al., 2008; Ruiz-Veguilla et al., 2008; Strauss et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013), whereas poor premorbid academic functioning has been specifically associated with greater neurocognitive and intellectual impairment, and earlier onset of prodromal symptoms (Allen et al., 2001; Larsen et al., 2004; Norman, Malla, Manchanda, and Townsend, 2005; Rund et al., 2007). In terms of differential trajectories of academic and social premorbid functioning across development, there is some evidence that premorbid academic functioning deteriorates more steeply from childhood across adolescence, compared to a more stable course of social premorbid adjustment (Monte, Goulding, and Compton, 2008; Barajas et al., 2013).

Investigations of premorbid adjustment trajectories show promise for detecting meaningful patterns of dysfunction prior to the onset of illness; however, prior studies have some limitations. Relatively few studies have examined these questions in first-episode samples, leaving questions about the potential risks of recall bias, inconsistency of illness phase across participants, and introduction of confounds known to influence psychotic symptomatology such as antipsychotic medications. Only one published investigation used state-of-the art empirical modeling techniques, which are able to examine a priori hypotheses in conjunction with plausible competing models (Cole et al., 2012); however, that study did not examine first-episode samples.

The current investigation sought to extend previous findings by examining trajectories of premorbid functioning in a sample of people seeking treatment for a first episode of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Specifically, we: 1) used growth mixture modeling (GMM) to evaluate competing models of trajectories of premorbid functioning across childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence in order to better identify and distinguish patterns of premorbid functioning, 2) assessed the clinical and demographic correlates of premorbid patterns at baseline, including their relationship to separate academic and social premorbid adjustment domains, and 3) for the sample for which we had conducted follow-up assessments, assessed the relationship of premorbid patterns to clinical outcomes at a 1-year follow-up. It was hypothesized that a 3-class model would provide the best fit for the data, comprised of stable-good, deteriorating, and stable-poor classes.

2.) Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 164 first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis patients who were recruited from inpatient units, outpatient evaluation services, or the emergency room of two separate clinical treatment services: the Payne Whitney Clinic (PWC) of the New York/Cornell University Medical Center (New York City; n = 52) and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC) of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Pittsburgh; n = 112). Participants were recruited at these two sites consecutively by the senior author (Haas) as part of a National Institute of Mental Health- (NIMH)-funded investigation of first-episode psychosis and, subsequently, as part of an NIMH-funded Conte Center Study of First Episode Psychosis. Protocols were consistent across the two sites, with the exception that follow-up data was collected only at WPIC, where support for multiple follow-up assessments was available. Of the 112 participants at WPIC, approximately half (n = 61) had available 1-year follow-up data. Participants were included if they met the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: presence of a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder (bipolar or depressed type), psychotic disorder NOS, or schizophreniform disorder.; no prior hospitalization for a psychotic episode; no prior full criteria for psychotic disorder met (by interview and medical chart review); English as the primary language; IQ > 75 (assessed using the Ammons Quick Test; Ammons and Ammons, 1962) ; no medical condition that could produce psychiatric symptoms or neurocognitive deficits (e.g., Alzheimer’s disorder); no current or recent (within the last six months) substance abuse; and no history of head trauma. The age range of participants was 15 to 50. Data were collected from 1987 to 2011. For the WPIC sample, 16 participants were not included because they did not meet diagnostic criteria, and 9 were excluded because of incomplete PAS data. For the Cornell sample, 10 participants were excluded because they did not meet diagnostic criteria.

Regarding diagnostic group selection, we wanted to focus on individuals who qualified for diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum psychotic disorders. Given that the natural course, treatment response and psychosocial features of delusional disorders and brief psychotic episodes are distinctively different from the schizophrenia spectrum disorder, we elected to exclude these cases from this study. The few cases that fell into psychotic disorders NOS were cases that had been judged by expert diagnostic consensus review to be sufficiently similar to schizophrenia (and unlike other psychotic disorders) to make it difficult to rule out the DSM diagnosis of schizophrenia and therefore, they fell into the psychotic disorders NOS and were included.

Selection also required availability of Premorbid Adjustment Scale data (PAS; Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982) which were not collected for a series of WPIC participants during a period of reduced funding for collection of PAS data (July 1998 through June 2003). Participants provided written informed consent according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board at both facilities, and written, informed consent was signed by a parent/guardian in the case of participants under age 18.

2.2 Assessment

2.2.1 Diagnostic assessment

Participants at both sites were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM- Axis I disorders (SCID-I; First et al., 2002) to evaluate current and lifetime Axis I psychiatric diagnoses. Clinical interviews were conducted by trained staff (Master’s- or Ph.D.-level psychologists or psychiatric nurses) and under the supervision of the investigators. Baseline assessments were 4–6 hours in length, conducted in 1 to 2 sessions within one week of intake, and follow-up assessments of global outcome were conducted at 1 year post-baseline. Diagnostic consensus meetings, conducted by senior clinicians and interviewers, used the LEAD (Longitudinal evaluation by Experts using All Data) approach to establish lifetime, multi-axial DSM-IV diagnoses (Spitzer, 1983). These consensus conferences used all available information, including patient report on the SCID-Patient Interview, outpatient therapist report, family report, and medical records, to establish, age at first psychotic symptom and date of psychotic episode onset. The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was calculated by subtracting the age at first psychotic symptom from the age at consent. In some cases, individuals had received a brief trial (by definition, less than four weeks) of antipsychotic medication. In addition to diagnostic assessment, information on demographics was collected at baseline and included patients’ sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status of the patients and their parents using the Hollingshead Index of Socioeconomic Status (Hollingshead, 1957; range: 11–66).

2.2.2 Premorbid functioning assessment

Premorbid functioning was assessed near discharge from hospital or for outpatients, at a stabilization assessment that was conducted at 4 to 8 weeks post-intake. It was assessed using the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS), a widely used retrospective rating scale, and medical record information to retrospectively assess functioning in social and academic settings prior to the onset of psychotic symptoms. The PAS assesses functional impairment at four periods: childhood (age 5–11), early adolescence (age 12–15), late adolescence (age 16–18), and adulthood (age 19 and above). Items tap functional impairment (e.g. social withdrawal and conflict) in social and academic settings across development, excluding items for academic settings from the period of adulthood. Items on the PAS are rated on a 0 – 6 scale, with ‘0’ representing good adjustment and higher ratings reflecting poorer adjustment. Total maladjustment ratings are generated for each age period and overall premorbid maladjustment.

In order to minimize the influence of prodromal and psychotic symptoms, PAS ratings exclude the 6 month period prior to estimated onset of the first florid psychotic symptom (Cannon-Spoor, Potkin, and Wyatt, 1982). In order to further account for the possible influence of the active phase of the psychotic disorder, the adult PAS data were excluded from the current study because of questions regarding its validity (Van Mastrigt and Addington, 2002). Thus, the current study utilized mean maladjustment ratings for childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence. The sample included 4 adolescents ages 15–17; for these cases, collateral information was also obtained from a parent or guardian.

2.2.3 Clinical symptom assessment

The present study examined clinical symptoms at the baseline and (for those available at the WPIC site) 1-year follow-up assessments. Participants completed assessment of positive and negative symptomatology via the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen, 1984a) and the Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1984b). The SAPS was designed to assess positive symptomatology, principally in schizophrenia, and items include the domains of hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and positive formal thought disorder. Each of these symptoms is rated on a six-point scale (0=none to 5=severe). The Modified SANS (NIMH Modified Version) was designed to assess negative symptomatology in schizophrenia, and includes the symptom domains of affective flattening-blunting, alogia, avolition-apathy, anhedonia-asociality, and inattention. Scores for each of these symptoms are rated on a five-point scale (1=normal to 5=severe dysfunction). SANS and SAPS total scores include a global score for each domain, and a SANS and SAPS mean score of all global items.

We estimated overall functioning at the time of assessment by administering the Strauss-Carpenter Level of Functioning Scale (LOF; Strauss and Carpenter, 1974), a 4-item scale that rates social functioning, work functioning, overall symptoms, and hospitalizations--each on a 5-point scale--with higher scores indicating better functioning in those domains. Global clinical status was evaluated using the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI; Guy, 1976) and global functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss et al., 1976), the forerunner of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale described in the DSM-IV-TR (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) The CGI is a rating of illness severity based on a 1–7 scale (1 = normal to 7 = extremely ill), and the GAS is an assessment of overall functioning rated on a numeric 1–100 scale, with 1 representing the worst functioning and 100 representing superior functioning.

2.3 Analyses

2.3.1 Growth Mixture Modeling Analysis

We examined different trajectories of premorbid adjustment by conducting growth mixture modeling analyses using Mplus version 5.2 (Muthén and Muthén, 2007). In contrast to other means for understanding heterogeneity in groups (e.g. cluster analysis), growth mixture modeling (GMM) is a person-centered approach that takes unobserved heterogeneity into account through estimating latent classes with potentially different trajectories over time as part of formal statistical models. GMM estimates a mean growth curve for each class, and, also importantly, allows for individual variation around these growth curves by estimating growth factor variances for each class (Muthén and Muthén, 2000). In our study, PAS scores in childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence were used to derive latent classes. We considered whether age, sex, race/ethnicity, diagnostic status, and study site accounted for differences within our sample by conducting analyses in which these served as potential covariates of PAS scores; however, they were unrelated to PAS scores, and therefore, were not retained in further analyses.

We examined the fit of models containing 1 to 7 classes (which included our hypothesized 3-class model). We used the “Mixture” analysis and permitted the intercept and slope variance terms to be estimated within class, but were constrained to be equal across classes. The best fitting model was determined by several goodness-of-fit statistics, including an entropy value as close to 1.0 as possible (indicating good classification quality), the sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), smaller values of which indicate superior model fit. Furthermore, the AIC and BIC penalize for more complex models. We used the parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test to evaluate whether the current K-class model (K classes) fit better than a K-1 model (wherein better fit is indicated by a significance test).

Lastly, we examined whether there were differences in clinical and demographic variables at baseline and at 1-year follow-up across classes defined by the best-fitting model using the Wald Test of Mean Equality. This test statistic examines mean differences in demographic and clinical variables across classes using “pseudoclass random draws,” a method using many random draws from each person’s posterior probability distribution to determine their class (Asparouhov and Muthen, 2007). We also conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA to separately examine the relationship of academic and social premorbid adjustment (PAS) scores to overall class membership.

3.) Results

3.1 Demographics

This sample of 164 first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis patients included 117 individuals with schizophrenia (71%), 34 (21%) with schizoaffective disorder, 11 (7%) with schizophreniform disorder, and 2 (1%) with psychotic disorder NOS. The mean age was 28.0 (SD =8.56); it was 62% male, and 59% European American in ethnicity. Participants had a mean Hollingshead Socioeconomic Status (SES) score of 32.3 (SD = 13.2). Mean number of years of duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) across the sample was 2.64 years (SD = 4.77; range: 0–28 years). See Table 1 for demographic data. Participants in the different diagnostic groups did not differ on PAS scores for any of the developmental periods: childhood, F(3, 160) = 1.61, p = .19; early adolescence, F(3, 160) = 1.91, p = .13; or late adolescence, F(3, 160) = 0.85, p = .47.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables and PAS Domain Scores Across the 3 Latent Classes

| “Stable Poor” (n = 88) | “Stable Good” (n = 65) | “Deteriorating” (n = 11) | Total Sample (N = 164) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) Age (years) | 28.34 (8.61) | 28.36 (8.85) | 23.63 (5.03) | 28.03 (8.56) |

|

| ||||

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | 56% | 69% | 64% | 62% |

| Female | 44% | 31% | 36% | 38% |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity: | ||||

| Caucasian | 61% | 55% | 55% | 59% |

| African-American | 31% | 30% | 45% | 31% |

| Other | 8% | 15% | 0% | 10% |

|

| ||||

| Diagnostic Group: | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 67% | 77% | 73% | 71% |

| Schizoaffective | 25% | 15% | 18% | 21% |

| Schizophreniform | 8% | 5% | 9% | 7% |

| Psychotic DO NOS | 0% | 3% | 0% | 1% |

|

| ||||

| a Academic PAS Score: [Mean (SD), Range: 0–6] | Post Hoc Tests (Tukey-B) | |||

| Childhood | 2.69 (0.98) | 0.90 (0.74) | 0.27 (0.47) | S-P >S-G >Det |

| Early Adolescent | 2.81 (1.22) | 1.55 (1.18) | 2.36 (1.42) | S-P, Det > S-G |

| Late Adolescent | 2.81 (1.43) | 1.74 (1.66) | 4.00 (1.18) | Det >S-P>S-G |

|

| ||||

| b Social PAS Score: [Mean (SD), Range: 0–6] | Post Hoc Tests (Tukey-B) | |||

| Childhood | 2.70 (0.91) | 1.07 (0.82) | 0.77 (0.91) | S-P > S-G, Det |

| Early Adolescent | 2.50 (1.00) | 1.28 (0.91) | 1.85 (1.39) | S-P > S-G, Det |

| Late Adolescent | 2.69 (1.19) | 1.53 (1.15) | 2.60 (0.94) | S-P, Det > G |

Results of 2-way (Class x Time) repeated measures analysis of variance on Academic PAS: Class: F(2,158) = 33.47; p<.0009; Repeated Measure (Time): F(2,157) = 51.52; p<.0009; Class x Time: F(4,314) = 16.25, p<.0009

Results of 2-way (Class x Time) repeated measures analysis of variance on Social PAS: Class: F(2,158) = 42.63; p<.0009; Repeated Measure (Time): F(2,157) = 21.38; p<.0009; Class x Time: F(4,314) = 9.60, p<.0009

Note: S-P = Stable Poor; S-G = Stable Good; Det = Deteriorating

Given that previous studies have found sex differences in the patterns of premorbid functioning and onset of psychotic symptoms, we examined sex differences in latent class membership and indicators of illness onset and course. As expected, males had a younger age of onset (m = 26.5, SD = 8.0) as compared with females (m = 30.5, SD = 8.9), t(162) = −3.05, p =.003. Sex was also examined in relation to onset of prodrome and prodrome length for those whose estimates of age at onset of prodrome were available (WPIC patients only); male/female differences in prodrome onset and prodrome length were not found. Male participants had lower mean socioeconomic status (SES) scores on the Hollingshead SES index (m = 30.0, SD = 13.4) relative to females (m = 35.9, SD = 12.3), t(91) = −2.11, p =.037. There were no sex differences in SES of participants’ parents, membership in the latent classes, baseline GAS scores, baseline SANS scores, or baseline SAPS scores.

3.2 Growth Mixture Modeling Analyses

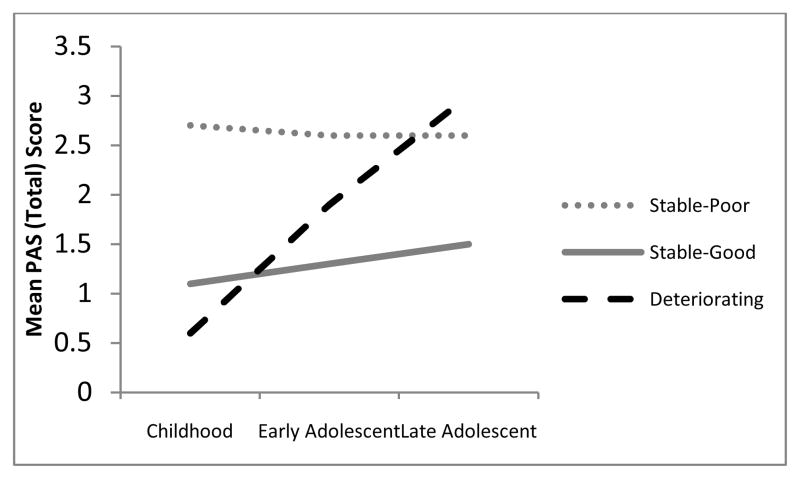

Table 2 presents the fit statistics for the 1–7 class models. As hypothesized, a 3-class model of premorbid adjustment provided the best fit. The 3-class model had the smallest values of AIC and sample size-adjusted BIC, and a high entropy value (i.e., above 0.80; Ramaswamy et al., 1993). Furthermore, a significant parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test indicated that this model provided significant improvement over a 2-class model, and the 4-class versus 3-class test was not significant. Within this 3-class model, the first class reflected “stable-poor” adjustment (54%), which reflected poor premorbid functioning in childhood that remained poor across early and late adolescence. The second class reflected “stable-good” adjustment (39%), with adequate to good functioning across childhood, and both early and late adolescence. The third class reflected “deteriorating” adjustment (7%), with good functioning at childhood and increasingly poor functioning across both early and late adolescence. The PAS scores for the 3-class model are presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Fit statistics for 1–7 class growth mixture models

| Fit Statistics

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample-Size Adjusted BIC | AIC | Entropy | Parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test | |

| 1-Class Model | 1176.01 | 1176.53 | n/a | n/a |

| 2-Class Model | 1154.04 | 1154.77 | 0.81 | −580.27*** |

| 3-Class Model | 1147.08 | 1148.00 | 0.82 | −566.39** |

| 4-Class Model | 1150.88 | 1152.00 | 0.76 | −560.00 |

| 5-Class Model | 1149.85 | 1151.18 | 0.82 | −559.00 |

| 6-Class Model | 1148.02 | 1149.54 | 0.87 | −555.59 |

| 7-Class Model | 1149.28 | 1151.00 | 0.87 | −557.97* |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 1.

Patterns of premorbid adjustment at three different developmental stages.

3.3 Differences Between Classes: Clinical and Demographic Variables

As indicated in Table 1, the three classes did not differ in terms of demographic variables. Table 3 presents means and standard deviations for clinical variables across the three classes, as well as scores for the Wald Test of Mean Equality to see if these variables differed among classes. In terms of clinical features at baseline, there were no differences across the three classes on clinical symptomology measures, nor on measures of functioning (GAS and LOF scales). Note that there were no differences between the WPIC and Cornell participants on any of the baseline PAS scores: childhood, t(162) = −1.32, p = .19; early adolescence, t(162) = −0.74, p = .48; or late adolescence, t(162) = −0.25, p = .80.

Table 3.

Baseline and Follow-up Clinical Variables Across the 3 Latent Classes

| Wald Mean Test of Equality | Stable-Good (n = 88) | Stable-Poor (n = 65) | Deteriorating (n = 11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ square | p-value | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |

| Years Duration Untreated Psychosis (DUP) | 2.08 | 0.35 | 2.64 (0.68) | 2.84 (0.56) | 1.47 (0.71) |

| GAS (baseline) | 0.40 | 0.82 | 29.41 (1.43) | 28.78 (0.95) | 27.48 (1.77) |

| GAS (1 year) | 0.07 | 0.96 | 46.88 (5.08) | 44.70 (3.30) | 42.85 (9.42) |

| Strauss-Carpenter (SC) Total (baseline) | 0.35 | 0.84 | 11.55 (0.71) | 10.67 (0.68) | 9.67 (2.19) |

| Strauss-Carpenter (SC) Total (1 year) | 5.35 | 0.07& | 12.24 (0.61) | 9.69 (0.55) | 9.06 (1.62) |

| SAPS Total (baseline) | 0.25 | 0.88 | 1.15 (0.10) | 1.20 (0.80) | 1.30 (0.20) |

| SAPS Total (1 year) | |||||

| SANS Total (baseline) | 0.18 | 0.91 | 1.55 (0.06) | 1.57 (0.05) | 1.53 (0.11) |

| SANS Total (1 year) | 7.56 | 0.02* | 1.09 (0.06) | 1.40 (0.06)a | 1.22 (0.20) |

| SANS Subscales: Alogia (baseline) | 0.65 | 0.72 | 1.86 (0.12) | 1.74 (0.09) | 1.56 (0.22) |

| Alogia (1 year) | 1.14 | 0.57 | 1.33 (0.09) | 1.41 (0.06) | 1.28 (0.14) |

| Aff. Flat. (baseline) | 1.50 | 0.47 | 2.22 (0.15) | 2.13 (0.12) | 1.69 (0.32) |

| Aff Flat. (1 year) | 0.96 | 0.62 | 1.90 (0.15) | 2.03 (0.14) | 1.67 (0.41) |

| Inattention (baseline) | 0.98 | 0.61 | 2.16 (0.15) | 1.91 (0.11) | 1.92 (0.28) |

| Inattention (1 year) | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.59 (.015) | 1.66 (0.18) | 1.76 (0.34) |

| Avolition-Apathy (baseline) | 0.57 | 0.75 | 2.47 (0.12) | 2.62 (0.12) | 2.56 (0.26) |

| Avolition-Apathy (1 year) | 10.40 | 0.01** | 1.50 (0.11) | 2.30 (0.15)a | 2.13 (0.38) |

| Anhedonia-Asociality (baseline) | 0.61 | 0.74 | 2.63 (0.15) | 2.83 (0.12) | 2.90 (0.27) |

| Anhedonia-Asociality (1 year) | 7.99 | 0.02* | 1.94 (0.16) | 2.69 (0.18)a | 2.04 (0.49) |

Note the abbreviations: GAS = Global Assessment Scale (Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss et al., 1976), SANS = Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1984b), SAPS = Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen, 1984a)

p = .07,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001; bold text indicates statistically significant findings

Stable-Poor > Stable-Good, p<.05

We also longitudinally examined clinical symptoms for the WPIC sample who were also assessed one year after baseline (n = 112); no follow-up data were collected at Cornell. The classes did not differ on SAPS or GAS scores at 1-year follow-up. Notably, there was a trend (p < .10) for an overall difference in functioning one year following baseline on the Strauss-Carpenter LOF Scale. Follow-up Wald Tests indicated that the “stable-good” class had higher overall functioning than the “stable-poor” class. In addition, at 1-year follow-up, participants in the “stable-poor” class had worse negative symptoms overall (total SANS score), and specifically, worse anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy relative to the “stable-good” class. Whereas those in the “stable-good” class experienced an improvement from baseline to 1-year follow up in some negative symptoms, those in the “stable-poor” class experienced consistently poor overall negative symptoms--driven by symptoms of anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy that persisted from baseline to 1-year follow-up. There were no differences in positive symptoms.

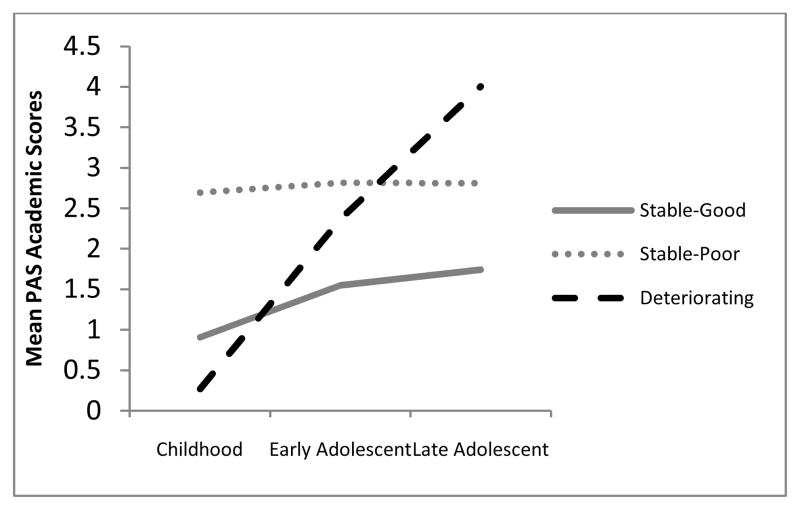

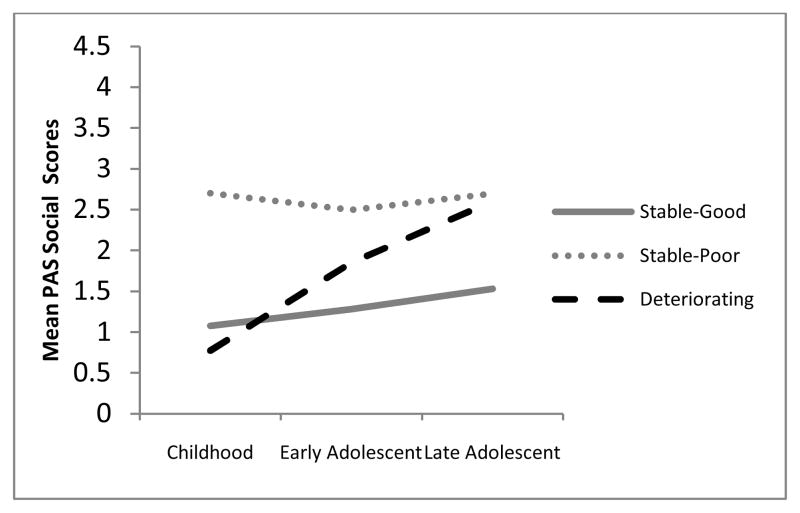

3.4 Relationship of Overall Classes to Separate Academic and Social Adjustment Domains

In order to examine the relationship of individual academic and social premorbid adjustment scores to the 3-class model of overall premorbid adjustment, we conducted a Reseated Measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction to examine the relationship of class membership of academic and social scores at each of the three time points (childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence). Consistent with the latent class growth modeling analysis, for premorbid social adjustment, we found a significant main effect for class, F(2, 158) = 42.63, p < .001, and also for time, F(1.8, 158) = 28.42, p < .001. Furthermore, the class by time interaction and was significant, F(3.63, 158) = 12.35, p < .001, suggesting that social scores across three time points varied differentially by class. Similarly, for premorbid academic adjustment, there was a significant main effect for time, F(1.8, 158) = 65.50, p < .001; for class, F(2, 158) = 33.47, p < .001; and for the interaction of time by class, F(3.58, 158) = 23.12, p < .001. An examination of these scores reveals that the trajectories for the academic and social domains are similar to each other and to the trajectories identified using latent class growth modeling of the overall PAS scores (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Relationship of overall premorbid adjustment latent classes with social adjustment.

Figure 3.

Relationship of overall premorbid adjustment latent classes with academic adjustment.

4.) Discussion

This study represents the first known latent class analysis examining premorbid patterns of functioning across developmental periods in individuals with a first-episode of a schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis. Findings suggest that premorbid developmental trajectories among individuals with a first episode of psychosis in schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses may be best characterized by one of three patterns of premorbid functioning: “stable-good” functioning, “stable-poor” functioning, or “deteriorating” functioning. These findings are consistent with the original proposal of three general patterns in a preliminary study by Haas and Sweeney (1992). Findings are also consistent with the cumulative evidence of substantial variability in the course of social maturation prior to the onset of the acute symptoms of schizophrenia (Tarbox and Pogue-Geile, 2008; Cole et al., 2012). Thus, growth mixture modeling is a statistical application that can be particularly useful in parsing the heterogeneity of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses across developmental periods, given that it takes into account individual variation around growth curves by estimating variances for each growth ‘class’ or, in this case, pattern of development.

Another strength of the current study--in terms of evaluating whether there are clinical differences associated with three trajectories of premorbid functioning--is that participants were recruited at a relatively uniform point in the course of their illness, i.e. at presentation to clinic at the time of the initial acute episode of psychosis. Moreover, we were able to examine a consecutive series of participants for whom data were collected at a standard interval following study entry and early in their recovery, i.e. one year following the onset of the initial episode. These data are consistent with prior studies of patients with first-episode schizophrenia in finding that poor premorbid functioning predicts worse negative-symptoms at clinical follow-up (e.g., Monte, Goulding, and Compton, 2008; Chang et al., 2013).

Limitations of the current study include limited sample size for analyses of follow-up data, as they were restricted to a single study site. First-episode cases were necessarily limited to those seeking treatment for a first episode of psychosis, a factor which may have excluded those with less severe initial episodes and/or who fail to seek treatment and thus may have inflated the proportion of people in the “stable-poor” class. Thus, these findings should be replicated in samples that include community-based individuals who are not treatment-seeking but meet clinical criteria for schizophrenia spectrum psychoses. Future studies should also include more representative numbers of adolescent participants. Given that this study was underpowered to simultaneously examine academic and social premorbid functioning in a single latent class growth model, questions remain about the ideal number of developmental trajectories when six parameters (three for academic and three for social adjustment) are included in the models. Additional studies with larger samples should carry out the latent class growth modeling approach analyzing academic and social function domains (6 parameters) simultaneously. This could provide a better examination of the social and academic domains of premorbid adjustment within growth mixture modeling analyses.

Given that the majority of the present sample appeared to evidence an ‘early hit’ to developmental processes in which functioning was consistently poor from early childhood through puberty and post-pubertal adolescence, these findings suggest that early childhood developmental abnormalities may be characteristic of a large subset of individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Findings from longitudinal studies of children at risk and studies of people who later develop schizophrenia suggest that subtle (“soft signs”) of neurological deficits and social impairment may emerge by middle childhood (Fish et al., 1992; Shiffman et al., 2004; Tarbox and Pogue-Geile, 2008). The current findings highlight a need for further study of early childhood development among those at risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses to help clarify when functional deficits emerge, for whom, and how these deficits may be related to neurodevelopmental differences.

In addition to deficits emerging in early childhood for a subgroup of individuals, we have also identified a subgroup having a ‘deteriorating’ course of social functioning between childhood and adolescence. These findings suggest that the pubertal period of development may be key to better understanding deficits in a relatively small subgroup of people with schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Accordingly, disrupted neurodevelopmental processes in the pubertal period are implicated in models of the development of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, including maturational increases in gonadal and adrenal hormones, disruption in the development of prefrontal cortical and limbic areas, increases in myelination, and synaptic pruning (Paus et al., 2008). Determining whether post-pubertal functional decline (prior to the development of prodromal and active symptoms) is associated with structural and functional alterations in brain development of a subset of individuals who go on to develop schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses will require further research. Furthermore, studies have differed on the proportion of people with schizophrenia with a deteriorating course of functioning, with estimates ranging from less than 10% to over 50% in different samples (Haas and Sweeney, 1992; Larsen, 1996; Cole et al., 2012) although all have used the same measure of premorbid adjustment (the PAS); thus, there is the need for additional prospective, longitudinal studies to generate reliable estimates of the proportions of people with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses who have intact functioning in childhood followed by a decline in functioning across adolescence. Future studies should also seek to identify clinical or temperamental characteristics (e.g., heightened stress sensitivity, poor adolescent social-sexual adaptation) that might differentiate individuals whose functioning declines at puberty or early adolescence from those whose functioning remains intact.

In the current study, meaningful clinical differences across the three groups did not emerge until one year following the acute phase of the first episode. For the patients who participated in longitudinal studies with follow-up data (WPIC only), there were no differences in positive symptoms at one-year follow-up, which was consistent with some prior studies of first-episode participants (e.g., Monte, Goulding, and Compton, 2008; Chang et al., 2013) and inconsistent with others (e.g., Addington, van Mastrigt, and Addington, 2003). Future studies should continue to examine long-term course of positive symptoms in relation to premorbid adjustment patterns. In terms of negative symptoms at one year follow-up, the ‘stable-poor’ group had higher anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy one year following their first treatment assessment, as compared to those in the “stable-good’ group, who experienced improvement in these negative symptom domains across one year (and for whom there was also a trend to have higher overall functioning one year after baseline). This specific finding of elevated anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy for the “stable-poor” class—but no differences between classes in the other negative symptoms domains—may extend prior findings of an association between poor premorbid functioning and elevated negative symptoms in general (Schmael et al., 2007). Previous comprehensive factor analytic studies of the SANS have found that the anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy subscales cluster together in an overall “social amotivation” factor in patients with schizophrenia (Mueser et al., 1994; Sayers et al., 1996) and first-episode psychosis (Malla et al., 2002). Consistent with the current findings, Sayers and colleagues also found that the “social amotivation” factor was associated with the existence of child behavior problems, poor premorbid functioning, and poor social adjustment.

Recent work on hedonic capacity in schizophrenia has suggested empirical reasons for why anhedonia-asociality and avolition-apathy SANS subscales comprise a distinct social amotivation factor--specifically, that this factor reflects an impaired ability to predict or anticipate the rewards of social encounters (“anticipatory pleasure”) in the context of an underlying intact capacity for enjoyment of social encounters (“consummatory pleasure”; Horan et al., 2006; Gard et al., 2007). Furthermore, early findings from functional neuroimaging studies in schizophrenia suggest that impaired reward prediction in schizophrenia may be driven by disrupted prefrontal-striatal interaction (Barch and Dowd, 2010), and that social amotivation (better understood as impaired anticipatory pleasure/goal-directed behavior) is a defining feature of negative symptoms (Foussias and Remington, 2010).

Future work should examine neurobiological differences in those at risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses across developmental periods to investigate the hypothesis that for a large subgroup of people with these disorders, anticipatory pleasure/goal-directed behavior deficits could emerge in childhood, underlie problems in social functioning, and persist in a trait-like fashion. Studies of this kind could contribute to improved identification of those at risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Findings from the current study support the potential value of conducting future investigations evaluating the relationship between premorbid functioning and treatment response. Given converging evidence that there are substantial individual differences among first-episode patients in the course of premorbid functioning, programmatic research is needed to develop personalized approaches to the specific treatment needs of individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses. Developmental trajectory classification many also help improve identification of people at earlier clinical stages of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, including the premorbid and prodromal stages (Tarbox et al., 2013), a necessary first step in developing interventions tailored for the unique needs of people at different clinical stages. Specifically, given the association between poor early premorbid adjustment and enduring negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, child- and adolescent-appropriate clinical interventions should be developed which target behaviors and skills contributing to poor social and academic adjustment.

In summary, the observation of varied trajectories of premorbid functioning in schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses may help guide future investigations of the prodrome and onset of these disorders and aid efforts to refine developmental models of these disorders. Further research should not only aim to better characterize deviations from normal patterns of behavioral development but also examine the possible neurobiological and neurocognitive correlates of these patterns. Finally, early detection of premorbid deficits may serve as a preventative public health strategy by identifying people at increased risk for schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses, potentially increasing the efficacy of early interventions in forestalling or preventing onset.

Highlights.

We examined patterns of premorbid adjustment in people with schizophrenia.

Unlike prior studies, we focused on people with first-episode schizophrenia.

We found 3 patterns of adjustment (“deteriorating,” “stable-poor,” “stable-good”)

These patterns may map onto disturbances in early childhood and pubertal development.

Those in the “stable-poor” class had worse negative symptoms at a 1-year follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This publication was supported by funds received MH48492 (PI: G L. Haas) and the UL1 RR024153 and NIH/NCRR/GCRC Grant M01 RR00056.

We thank Raymond Cho, MD, Gordon Frankle MD, Matcheri S. Keshavan MD, and the clinical core staff of the Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders (MH45156, MH084053, David Lewis MD, Director) for assistance in assessments, and Wayne Dickey, Ph.D. for assistance with the literature review. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Leslie E. Horton, Email: hortonle2@upmc.edu, Department of Psychiatry, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213.

Sarah I. Tarbox, Email: sarah.tarbox@yale.edu, Dept. of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 Park Street, New Haven, CT 06159.

Thomas M. Olino, Email: thomas.olino@temple.edu, Department of Psychiatry, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213.

Gretchen L. Haas, Email: haasgl@upmc.edu, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, phone: (412) 624-5627, fax: (412) 624-4496.

References

- Addington J, Addington D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first episode psychosis: Initial presentation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;112:40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first-episode psychosis: initial presentation. Schizophrenia Research. 2003;62:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DN, Kelley ME, Miyatake RK, Gurklis JA, Jr, van Kammen DP. Confirmation of a two-factor model of premorbid adjustment in males with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001:39–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4 Author; Washington, DC: 2000. -TR. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Author; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ammons RB, Ammons CH. Quick Test. Psychological Test Specialists; Oxford: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) University of Iowa; Iowa City: 1984a. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) University of Iowa; Iowa City: 1984b. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Wald test of mean equality for potential latent class predictors in mixture modeling. Unpublished technical paper. 2007;2007 Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas A, Usall J, Banos I, Dolz M, Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Autonell J, Sanchez B, Cervilla JA, Foix A, Obiols JE, Haro JM, Ochoa S GENIPE group. Three factor model of premorbid adjustment in a sample with chronic schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2013;151:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Dowd EC. Goal representations and motivational drive in schizophrenia: The role of prefrontal-striatal interactions. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:919–934. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard-Evans L, Iyer S, Lepage M, Joober R, Malla A. Investigating cognitive deficits and symptomatology across pre-morbid adjustment patterns in first-episode psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:749–759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Jones P, Gilvarry C, Rifkin L, McKenzie K, Foerster A, Murray RM. Premorbid social functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Similarities and differences. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1544–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1982;8:470–484. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Man Tang JY, Hui CLM, Hoi YW, Chan SKW, Lee EHM, Chen EYH. The relationship of early premorbid adjustment with negative symptoms and cognitive functions in first-episode schizophrenia: A prospective three-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Research. 2013;209:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole VT, Apud JA, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Using latent class growth curve analysis to form trajectories of premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:388–395. doi: 10.1037/a0026922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran C, Davidson L, Sills-Shahar R, Nickou C, Malaspina D, Miller T, McGlashan T. A qualitative research study of the evolution of symptoms in individuals identified as prodromal to psychosis. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2003;74:313–332. doi: 10.1023/a:1026083309607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey WC, Haas GL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Gender and familial history as predictors of patterns of premorbid functioning in first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147(11):216–216. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AE, McGuffin P, Spitznagel EL. Heterogeneity in schizophrenia: A cluster-analytic approach. Psychiatry Research. 1983;8:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(83)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV –TR Axis I Disorders (SCIP-I/P) Biometrics Research; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fish B, Marcus J, Hans SL, Auerbach JG. Infants at risk for schizophrenia: sequelae of a genetic neurointegrative defect. A review and replication analysis of pandysmaturation in the Jerusalem Infant Development Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:221–235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820030053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foussias G, Remington G. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Avolition and Occam’s Razor. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:359–369. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Kring AM, Germans Gard M, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: Distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (revised) National Institute of Mental Health; Bethesda MD: 1976. Clinical Global Impression; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Haas G, Sweeney JA. Premorbid and onset features of first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18:373–386. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haim R, Rabinowitz J, Bromet E. The relationship of premorbid functioning to illness course in schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders during two years following first hospitalization. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:791–795. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000240158.39929.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two Factor Index of Social Position. Yale Station; New Haven, Conn: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Abel MB, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Jorgensen P, Nordentoft M. The association between pre-morbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first episode psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1157–1166. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TK, Friis S, Haahr U, Johannessen JO, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Rund BR, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan TH. Premorbid adjustment in first-episode nonaffective psychosis: distinct patterns of pre-onset course. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;185:108–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TK, Friis S, Melle IU, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannessen JO, McGlashan TH, Opjordsmoen S, Rund BR, Simonsen E, Vaglum P. Premorbid functioning in first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;53:56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TR, McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO, Vibe-Hansen L. First-episode schizophrenia: II. Premorbid patterns by gender. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22:257–269. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla AK, Takhar JJ, Norman RMG, Manchanda R, Cortese L, Haricharan R, Verdi M, Ahmed R. Negative symptoms in first episode non-affective psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:431–439. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan J, Breiger D, McCurry C, Hilastala SA. Premorbid functioning in early-onset psychotic disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:666–672. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046844.56865.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD. Issues for DSM-V: Clinical staging: A heuristic pathway to valid nosology and safer, more effective treatment in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:859–860. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A, Reicher-Rossler A, Meisenzahl EM, Tognin S, Wood S, Borgwardt SJ, Koutsouleris N, Yung AR, Stone JM, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Valli I, Velakoulis D, Woolley J, Pantelis C, McGuire P. Neuroanatomical abnormalities that precede the onset of psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:489–495. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE. Schizotaxia revisited. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:935–944. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte RC, Goulding SM, Compton MT. Premorbid functioning of patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis: A comparison of deterioration in academic and social performance, and clinical correlates of Premorbid Adjustment Scale scores. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;104:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Sayers SL, Schooler NR, Mance RM, Haas GL. A multisite investigation of the reliability of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1453–1462. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Reddy R, Schnur DB. A developmental model of negative syndromes in schizophrenia. In: Greden J, Tandon R, editors. Negative schizophrenic symptoms: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. 175–185. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Author; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Jalbrzikowski M, Bearden CE. Exploring predictors of outcome in the psychosis prodrome: implications for early identification and intervention. Neuropsychological Reviews. 2009;19:280–93. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RMG, Malla AK, Manchanda R, Townsend L. Premorbid adjustment in first episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders: A comparison of social and academic domains. Blackwell Munksgaard. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;112:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:947–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo WS, Reibstein DJ, Robinson WT. An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. 1993;12:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Veguilla M, Cervilla JA, Barrigon ML, Ferrin M, Gutierrez B, Gordo E, Anguita M, Brana A, Fernandez-Logrono J, Gurpegui M. Neurodevelopmental markers in different psychopathological dimensions of first episode psychosis: The ESPIGAS Study. European Psychiatry. 2008;23:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Melle I, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Midboe LJ, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan T. The course of neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis and its relation to premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis, and relapse. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;91:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Curran PJ, Mueser KT. Factor structure and construct validity of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Schmael C, Georgi A, Krumm B, Buerger C, Deschner M, Nothen MM, Schulze TG, Reitschel M. Premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia: An important aspect of phenotype definition. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;92:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham PC, Castle DJ, Wessely S, Farmer AE, Murray RM. Further exploration of a latent class typology of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1996;20:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman J, Walker E, Ekstrom M, Schulsinger F, Sorensen H, Mednick S. Childhood videotaped social and neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2021–2027. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer M. Psychopathology, A Case Book (with Janet BW Williams and Andrew E. Skodol. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Allen DN, Miski P, Buchanan RW, Kirpatrick B, Carpenter WT., Jr Differential patterns of premorbid social and academic deterioration in deficit and deficit schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;135:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JS, Carpenter WT. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia II. Relationships between predictor and outcome variables: a report from the WHO international pilot study of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;3:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760130021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous RD, Alvir JMJ, Robinson D, Gal G, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Lieberman JA. Premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: Relation to baseline symptoms, treatment response, and medication side effects. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(2):265–278. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox SI, Addington J, Cadenhead K, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, Perkins D, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker E, Heinssen R, McGlashan T, Woods SW. Premorbid functional development and conversion to psychosis in clinical high-risk youth. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1173–1188. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox S, Pogue-Geile M. Development of social functioning in preschizophrenia children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;34:561–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.34.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kammen DP, Kelley ME, Gilbertson MW, Gurklis J, O’Connor DT. CSF dopamine b-hydroxylase in schizophrenia: Associations with premorbid functioning and brain computerized tomography scan measures. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:372–378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mastrigt S, Addington J. Assessment of premorbid function in first episode schizophrenia: Modifications to the Premorbid Adjustment Scale. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2002;27:92–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]