Abstract

The neuroimmunological kynurenine pathway (KP) has been implicated in major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults and adolescents, most recently in suicidality in adults. The KP is initiated by the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which degrades tryptophan (TRP) into kynurenine (KYN) en route to neurotoxins. Here, we examined the KP in 20 suicidal depressed adolescents—composed of past attempters and those who expressed active suicidal intent—30 non-suicidal depressed youth, and 22 healthy controls (HC). Plasma levels of TRP, KYN, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, and KYN/TRP (index of IDO) were assessed. Suicidal adolescents showed decreased TRP and elevated KYN/TRP compared to both non-suicidal depressed adolescents and HC. Findings became more significantly pronounced when excluding medicated participants, wherein there was also a significant positive correlation between KYN/TRP and suicidality. Finally, although depressed adolescents with a history of suicide attempt differed from acutely suicidal adolescents with respect to disease severity, anhedonia, and suicidality, the groups did not differ in KP measures. Our findings suggest a possible specific role of the KP in suicidality in depressed adolescents, while illustrating the clinical phenomenon that depressed adolescents with a history of suicide attempt are similar to acutely suicidal youth and are at increased risk for completion of suicide.

Keywords: tryptophan; 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; adolescence; depression; suicide

1. INTRODUCTION

Suicide is among the most serious health problems for children and adolescents in the United States. According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide has become the second leading cause of death among children aged 12–17 years after non-intentional injuries and ahead of homicides and malignancies, respectively (Perou et al., 2013). The two most prominent risk factors for completed suicide in youth are a past suicide attempt and a diagnosis of a depressive episode, each independently representing a 10–30 fold increased risk for completed suicide (Shaffer et al., 1996). Consequently, depressed adolescents with a past suicide attempt are at high risk for completion of suicide (Brent et al., 1993).

There has been sparse research into the neurobiology of suicide. Clinical and postmortem work has mainly focused on the monoamine system, documenting serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine deficiency with limited progress on the contributory biology. Over the past decade there has been a shift in research from the monoamine system to complex mechanisms that induce neuroplasticity impairment, such as inflammation and glutamatergic excitotoxicity. The neuroimmunological kynurenine pathway (KP) is hypothesized to play a key role in such processes, linking peripheral inflammation and glutamate disturbances (Laugeray et al., 2010). The KP (illustrated in Figure 1) is activated by the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and is the rate-limiting enzyme of the pathway. IDO metabolizes tryptophan (TRP) into kynurenine (KYN), thereby reducing TRP availability for 5-HT synthesis. KYN by itself is not neuroactive, but crosses the blood brain barrier to generate free-radical-producing 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3- HAA) or the glutamatergically-active kynurenine metabolite quinolinic acid (QUIN). Conversely, KYN can also be metabolized into kynurenic acid (KA), which is a glutamate receptor antagonist, constituting the neurotrophic branch of the KP. Converging evidence dating back to the 1970s has implicated the KP neurotoxic branch with MDD (Curzon and Bridges, 1970; Heyes et al., 1992; Laugeray et al., 2010). Work from our laboratory documented relationships between KP activation and anhedonia (Gabbay et al., 2010a; Gabbay et al., 2012) in adolescents with MDD. More recently, the KP has been associated specifically with suicidality in adults (Sublette et al., 2011; Erhardt et al., 2013; Bay-Richter et al., 2015). Findings included elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) QUIN levels in suicide attempters across psychiatric disorders compared to healthy control adults (Erhardt et al., 2013; Bay-Richter et al., 2015). However, these studies did not include a non-suicidal psychiatric group and thus, findings may be related to the psychiatric condition rather than the suicidal behavior. In a separate study, plasma KYN, TRP, and IDO (indexed by KYN/TRP) were examined, with only KYN levels elevated in depressed patients with a history of suicide attempt compared to those who had never attempted suicide (Sublette et al., 2011). However, there was no acutely suicidal subgroup.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of the Kynurenine Pathway. Note, * indicates metabolites that cross the blood-brain barrier.

Based on the above observations, we sought to examine the KP in depressed suicidal adolescents, composed of both past attempters and those who expressed active suicidal intent, compared to non-suicidal depressed adolescents and healthy controls (HC). Hypotheses were that depressed suicidal adolescents would exhibit increased KP activation, indexed by increased IDO (quantified by KYN/TRP), KYN and 3-HAA, and decreased TRP. Since psychotropic medications are known to have anti-inflammatory effects (Kostadinov et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014; Obuchowicz et al., 2014), analyses were repeated while excluding medicated participants. Finally, we explored whether KP metabolites differed between subgroups of depressed adolescents who were actively suicidal and those with prior attempts, both of which were included in the suicidal group.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The current sample is part of previous published studies examining a) plasma cytokine levels in suicidal depressed adolescents (Gabbay et al., 2009) and b) the KP in adolescent MDD (Gabbay et al., 2010a). Participants were 30 non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (mean age = 15.21, SD = 1.93, 12 females), 20 adolescents with MDD and at high risk for suicide (actively suicidal or previous attempt; mean age = 16.82, SD = 1.84, 15 females), and 22 healthy controls (HC; mean age = 15.96, SD = 2.64, 13 females). The entire MDD group (n = 50) and healthy controls (n = 22) were matched on age and gender; however, suicide subgroups were not specifically matched on these variables. Therefore, age and gender were included in statistical models.

Adolescents with MDD (both suicidal and non-suicidal) were enrolled from the New York University (NYU) Child Study Center, the NYU Tisch inpatient psychiatric unit, and the Bellevue Department of Psychiatry. The healthy controls were recruited from the New York Metropolitan area. This study received NYU School of Medicine IRB approval. Participants aged 18 and older (n = 14) provided signed informed consent; those under age 18 provided assent, and a parent or guardian provided signed consent.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for all subjects included: immune-affecting medications taken in the past 6 months, any immunological or hematological disorder, chronic fatigue syndrome, any infection during the month prior to the blood draw (including the common cold), significant medical or neurological disorders, and in females, a positive urine pregnancy test. For subjects with MDD, the following disorders were exclusionary: (1) schizophrenia, (2) pervasive developmental disorder, (3) posttraumatic stress disorder, (4) obsessive-compulsive disorder, (5) Tourette’s disorder, (6) eating disorder, and/or (7) a substance-related disorder in the past 3 months (based on history and urine toxicology test). Due to recruitment challenges, especially of patients expressing active suicidal intent and the need to start treatment as soon as possible, psychotropic medication treatment was not exclusionary for adolescents with MDD. Healthy controls could not have any major current or past psychiatric diagnosis as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev., DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and could not be taking psychotropic medications.

Adolescents with MDD were required to have a depressive episode lasting at least 6 weeks and a minimum severity score of 36 on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRSR). Adolescents at high risk for suicide all met MDD criteria and were either expressing active suicidal intent and were thus hospitalized inpatients or had a past suicide attempt. Previous suicide attempts were differentiated from self-harm behavior without suicidal intent as serious incidents that would have resulted in death if not intervened, such as hanging, overdose, and ingestion of toxic materials.

2.3. Assessments

Baseline assessment consisted of both psychiatric and medical evaluations. To determine psychiatric status, a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist (V.G., C.A.) interviewed subjects and parents at the NYU Child Study Center using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version for Children (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997). Additional assessments included the CDRS-R, the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), and the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II).

2.3.1. Suicidality

Suicidal ideations were assessed by the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI). The BSSI has two subscales with a subtotal maximum score of 10 for subscale 1 and of 32 for subscale 2. Per the instructions, participants who answered “0” on questions 4 and 5 of subscale 1 did not proceed to subscale 2. Therefore, only those participants who completed both parts 1 and 2 of the BSSI questionnaire were included in the correlational analyses that assessed the relation between KP metabolites and suicidality, to ensure that participants’ scores were based on the same final total.

2.3.2. Medical assessments

Baseline evaluations included medical history and laboratory tests, containing complete blood count, metabolic panel, liver and thyroid function tests, a urine toxicology test (assessing amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, marijuana, methadone, opiates, phencyclidine, and propoxyphene), and a pregnancy test for females.

2.4. Determination of kynurenine pathway metabolite concentrations

All blood samples (10 mL) were drawn in the morning following a 12-hour overnight fast. Samples were processed within 20 minutes of collection and stored at −80°C. All analyses were conducted while blind to the clinical status of participants. Analyses of TRP, KYN, and 3-HAA were done by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and are detailed in Gabbay et al. (2010a).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were computed using SPSS, version 20. Descriptive statistics including frequency distributions, measures of central tendency, and variance were used to describe the groups on demographic and clinical variables. Groups were compared on these variables using analysis of variance (ANOVA), t-tests, and chi-square tests where appropriate. When underlying assumptions were violated, non-parametric analogs were employed. Distributions of the KP metabolites were positively skewed, so Quade’s (1967) non-parametric analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) based on ranks compared KP plasma levels [i.e. TRP, KYN, 3-HAA, KYN/TRP (index of IDO activity)] between groups, adjusting for age and gender. A priori comparisons between groups were carried out only for significant composite F tests using Fisher’s least significant difference procedure. Spearman rank correlations assessed the relation between KP metabolites and suicidality as measured by the BSSI. Statistical significance was defined as two-sided p < 0.05, and trending towards significance was defined as p < 0.10. All tables display raw KP plasma levels for ease of interpretation.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic and clinical features

Demographic and clinical characteristics of non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (n = 30), adolescents with MDD at high risk for suicide (n = 20), and healthy controls (n = 22) are summarized in Table 1. The MDD sample at high risk for suicide consisted of 11 actively suicidal adolescents and 9 with a previous suicide attempt. The most common previous attempt was overdoing on medications, followed by hanging. Two adolescents previously attempted suicide more than once. Active suicidal attempts also included going to the roof with a plan to jump, drinking household cleaners, or trying to stab themselves.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population across diagnostic groups.

| Characteristic | Suicidal MDD (n = 20) |

Non-suicidal MDD (n = 30) |

HC (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean ± SD] | 16.82 ± 1.84a | 15.21 ± 1.93a | 15.96 ± 2.64 |

| Gender [n female] (%) | 15 (75.00)a | 12 (40.00)a | 13 (59.09) |

| Ethnicity [n Caucasian/African American/ Other] (%) | 9/5/6 (45/25/30) | 17/1/12 (57/3/40) | 13/2/7 (59/9/32) |

| Illness History | |||

| Episode Duration in Months [mean ± SD] (Range) | 19.50 ± 18.40 (3–84) | 18.75 ± 16.11 (1.5–72) | 0 |

| Past Suicide Attempts [% 0/1/2/3] | 10/60/20/10 | 100/0/0/0 | 100/0/0/0 |

| Medication Status [n] (%) | |||

| Medicated | 13 (65.00) | 4 (13.33) | 0 |

| Medication Free | 2 (10.00) | 3 (10.00) | 0 |

| Medication Naïve | 5 (25.00) | 23 (76.67) | 22 (100) |

| CDRS-R1 [mean ± SD] (Range) | 64.40 ± 15.56b (36–97) | 51.86 ± 10.42c,+ (37–81) | 18.27 ± 2.47b,c (17–27) |

| BDI-II2 [mean ± SD] (Range) | 26.44 ± 11.47++ (8–53) | 19.60 ± 9.55 (4–44) | 2.00 ± 2.71 (0–11) |

| BSSI3 [mean ± SD] (Range) | 14.47 ± 8.75a,b,+ (2–24) | 2.60 ± 4.36a (0–15) | 0.09 ± 0.29b (0–1) |

| Anhedonia [mean ± SD] (Range) | 7.39 ± 2.97b,++ (1–13) | 5.93 ± 2.43c,+ (1–10) | 1.18 ± 0.39b,c (1–2) |

Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition

Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal and non-suicidal MDD subgroups differed significantly with respect to age (p = 0.03), gender (p = 0.015), and suicidal ideation (BSSI; p < 0.0005), but not ethnicity (p = 0.069), CDRS-R (p = 0.115), or anhedonia (p = 0.693).

The suicidal MDD and HC groups differed significantly with respect to CDRS-R (p < 0.0005), BSSI (p < 0.0005), and anhedonia (p < 0.0005), but not age (p = 0.400), gender (p = 0.275), or ethnicity (p = 0.368).

The non-suicidal MDD and HC groups differed significantly with respect to CDRS-R (p < 0.0005) and anhedonia (p < 0.0005), but not age (p = 0.429), gender (p = 0.173), ethnicity (p = 0.614), or BSSI (p = 0.190).

Missing data from 1 participant.

Missing data from 2 participants.

Seventeen adolescents with MDD (34%) were treated with psychotropic medications at the time of blood draw but had failed to respond to treatment. Of these participants, 13 were in the group at high risk for suicide (11 with active intent and 2 with past attempt) and 4 were nonsuicidal. Medications included bupropion, citalopram, fluoxetine, lamotrigine, lithium, methylphenidate, mirtazapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertraline, and mixed amphetamine salts. Thirty-three adolescents with MDD (66%) were non-medicated, 28 of whom were medicationnaïve and 5 of whom were psychotropic medication-free for at least one year.

The entire group of adolescents with MDD (n = 50) and healthy controls (n = 22) were not significantly different in age [t(70) = 0.186, p = 0.853], gender [χ2(1) = 0.160, p = 0.689], or ethnicity (i.e. Caucasian, African American, Other) [χ2(2) = 0.335, p = 0.846]. However, suicidal and non-suicidal MDD subgroups differed significantly with respect to age and gender (Table 1).

3.2. Clinical comparisons between groups

As expected, a Kruskal-Wallis test determined that illness severity, as measured by the CDRS-R, was significantly different between the three groups [χ2(2) = 49.58, p < 0.0005]. The non-suicidal MDD (p < 0.0005) and suicidal MDD (p < 0.0005) groups both had higher CDRS-R scores than healthy controls, but the MDD groups were not significantly different (p = 0.115).

Anhedonia scores were also significantly different between the three groups [χ2(2) = 40.34, p < 0.0005]. Similarly to depression severity, both suicidal (p < 0.0005) and non-suicidal (p < 0.0005) groups scored higher than healthy controls, but the MDD groups were not significantly different (p = 0.693).

Lastly, scores on the BSSI were significantly different between the three groups [χ2(2) = 42.26, p < 0.0005]. Suicidal depressed adolescents had elevated suicidal ideation compared to both the non-suicidal MDD (p < 0.0005) and HC groups (p < 0.0005) as expected. However, the healthy controls did not differ from non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.190).

3.3. Group differences in KP metabolites

KP metabolite means, standard deviations, and comparisons are summarized in Table 2. The composite F-tests from non-parametric ANCOVAs controlling for age and gender yielded significant differences between the three groups in TRP [F(2,67) = 4.70, p = 0.012] and KYN/TRP (IDO) [F(2,67) = 3.25, p = 0.045] plasma levels (Figure 2). However, there were no differences between groups with respect to KYN [F(2,69) = 1.23, p = 0.299] and 3-HAA [F(2,69) = 1.35, p = 0.267].

Table 2.

Mean (SD) plasma concentrations (in ng/ml) of kynurenine (KYN), tryptophan (TRP), 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), and the KYN/TRP ratio, an index of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity in suicidal adolescents with MDD, non-suicidal adolescents with MDD, and healthy controls (HC).

| Measure | Suicidal MDD (n = 20) |

Non-suicidal MDD (n = 30) |

HC (n = 22) |

Group Effect p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KYN | 324.64 (98.43) | 407.23 (150.40) | 408.65 (148.08) | 0.299 |

| TRP | 609.07a,+ (343.00) | 1092.13b (782.39) | 982.87+ (406.31) | 0.012* |

| 3-HAA | 8200.45 (1977.20) | 9774.74 (2545.74) | 9630.58 (2251.77) | 0.267 |

| KYN/TRP (IDO) | 0.69c,+ (0.38) | 0.50d (0.29) | 0.49+ (0.27) | 0.045* |

Note: Group effect is for the rank-based ANCOVA controlling for age and gender

indicates significance at p < 0.05.

Missing data from 1 participant.

Compared to HC (p = 0.006); excluding medicated participants (p = 0.005).

Compared to suicidal MDD (p = 0.013); excluding medicated participants (p = 0.008).

Compared to HC (p = 0.043); excluding medicated participants (p = 0.018).

Compared to suicidal MDD (p = 0.019); excluding medicated participants (p = 0.011).

Fig. 2.

Group Differences in TRP and KYN/TRP (Index of IDO) Plasma Levels (in ng/ml). A) Differences between healthy controls, non-suicidal adolescents with MDD, and suicidal adolescents with MDD. B) Group differences when medicated participants were excluded. * indicates a significant difference between groups (p < 0.05).

3.3.1. TRP plasma levels

Suicidal adolescents with MDD had significantly lower TRP than both healthy controls (p = 0.006) and non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.013). There were no significant differences between healthy controls and non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.580).

3.3.2 KYN/TRP plasma levels

Suicidal adolescents with MDD had significantly higher KYN/TRP levels than both healthy controls (p = 0.043) and non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.019). There were no significant differences between healthy controls and non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.853).

3.4. Correlations between suicidality and KP measures

In all adolescents with MDD (i.e. non-suicidal MDD and suicidal MDD subgroups) who completed both parts 1 and 2 of the BSSI (n = 20), Spearman correlations showed no significant relations between raw plasma levels of TRP (p = 0.080), KYN (p = 0.191), KYN/TRP (IDO) (p = 0.180), or 3-HAA (p = 0.623) and suicidality. Additionally, the rank transformed analogs were not correlated (all p > 0.05).

3.5. Excluding medicated adolescents with MDD

Results remained significant when non-parametric ANCOVAs controlling for age and gender were rerun to compare the three groups (i.e. HC, non-suicidal MDD, suicidal MDD) excluding medicated adolescents with MDD. TRP levels were significantly reduced in suicidal adolescents compared to healthy controls (p = 0.005) and non-suicidal adolescents with MDD (p = 0.008). Additionally, KYN/TRP was elevated in the suicidal MDD group compared to both the HC (p = 0.018) and non-suicidal MDD groups (p = 0.011). There were no significant differences in any metabolites between the non-suicidal MDD and HC groups (Figure 2).

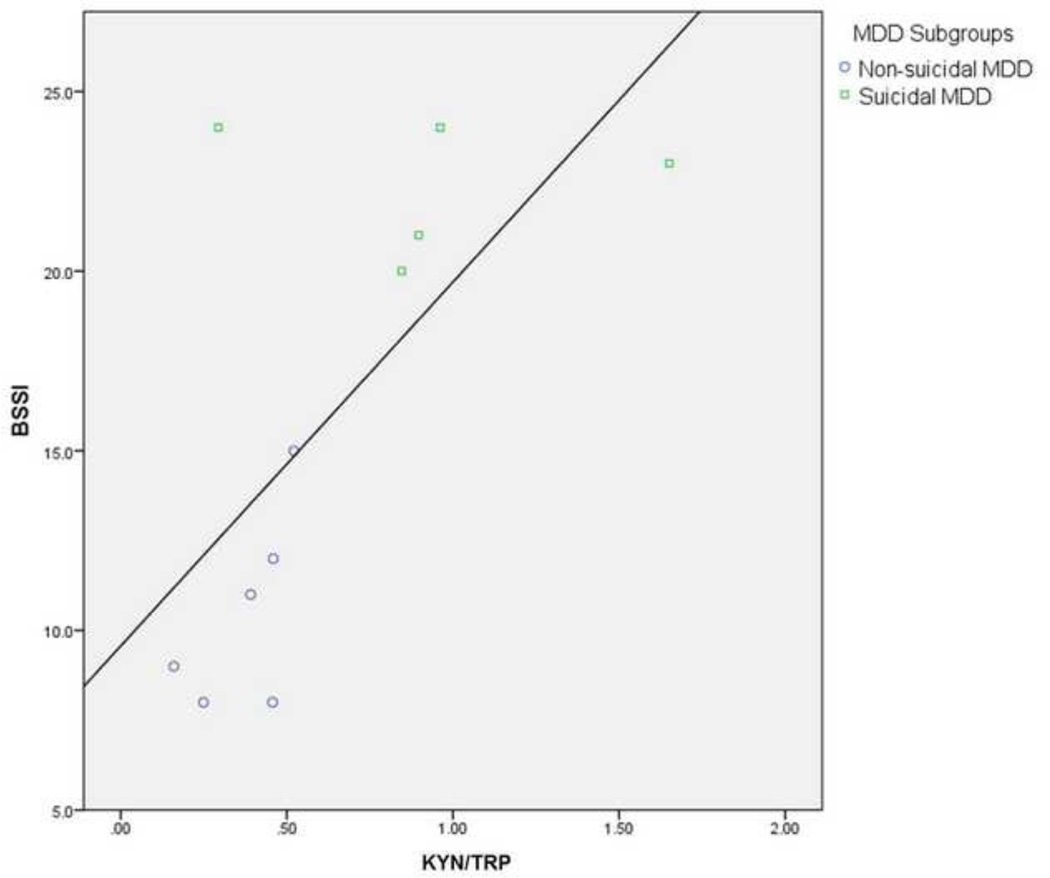

Results of Spearman correlations were different when medicated depressed adolescents were excluded. There was a significant positive correlation between KYN/TRP plasma levels and BSSI scores [rs (n = 11) = 0.63, p = 0.038]. The negative correlation between TRP and BSSI scores approached significance [rs (n = 11) = −0.59, p = 0.057]. A graph of the KYN/TRP correlation can be seen in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

Correlation Between BSSI Scores and KYN/TRP (Index of IDO) (in ng/ml). Only unmedicated adolescents with MDD that completed both sections of the BSSI (n=11) were included. The correlation between BSSI and KYN/TRP (index of IDO) was significant, [rs=0.63, p=0.038].

3.6. Exploratory analyses

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine differences within the suicidal MDD group (n = 20) between acutely suicidal adolescents (n = 11) and those with a history of suicide attempt (n = 9). Mann-Whitney U-tests revealed that adolescents with a history of suicide attempt (mean CDRS-R = 56.25, SD = 10.87) were significantly different from acutely suicidal adolescents (mean CDRS-R = 72.60, SD = 13.45) with respect to disease severity [U = 87.00, p = 0.003]. Additionally, acutely suicidal adolescents (mean anhedonia = 8.90, SD = 2.77) had significantly increased anhedonia compared to those with prior suicide attempts [mean anhedonia = 5.50, SD = 2.07; U = 67.50, p = 0.012]. Lastly, acutely suicidal adolescents (mean BSSI = 19.6, SD = 5.89) showed increased suicidality on the BSSI compared to those with a history of suicide attempt [mean BSSI = 7.00, SD = 6.34; U = 82.50, p = 0.001].

Despite these behavioral differences, actively suicidal adolescents and those with a history of suicide attempt were neurobiologically similar with respect to KP metabolites. Non-parametric ANCOVAs controlling for age and gender yielded no significant differences between these suicidal subgroups in TRP (p = 0.103), KYN/TRP (p = 0.118), KYN (p = 0.166), or 3-HAA (p = 0.960). Analyses could not be repeated excluding medicated participants, as 13 out of 20 suicidal adolescents were taking psychotropic medications.

4. DISCUSSION

As hypothesized, our findings suggest a role for the KP in suicidality in adolescents with MDD. Specifically, we documented that depressed adolescents who are considered at high risk for suicide (i.e. acutely suicidal or history of attempt) exhibited decreased TRP and increased KYN/TRP (index of IDO activity) compared to non-suicidal depressed adolescents and healthy controls. However, our other hypotheses pertaining to KYN and 3-HAA were not supported. Our second major finding was that when participants treated with psychotropic medications were excluded, differences became more significantly pronounced, and the KYN/TRP ratio was also found to positively correlate with suicidal scores in the depressed group. Lastly, when differences were explored between the depressed suicidal subgroups—those with a history of suicide attempt and those who acutely expressed suicidal intent—no differences were found in TRP or KYN/TRP plasma levels despite significant differences in anhedonia and depression severity.

Our findings replicate prior studies documenting monoamine deficiency (Mann et al., 1996), particularly of the serotonergic precursor TRP in suicidal populations. Investigations in both children (Pfeffer et al., 1998) and adults (Almeida-Montes et al., 2000) have found decreased levels of TRP in suicide attempters compared to non-attempters. Additionally, both a diagnosis of major depression and serum TRP levels predicted suicidal behavior in a study of teenagers with alcohol use disorders (Clark, 2003). While this evidence supports our finding of decreased TRP in suicidal depressed adolescents, there is also substantiation that TRP may not be a distinctive marker for suicidality. For example, Roggenbach et al. (2007) found no differences in TRP between suicidal psychiatric inpatients and non-suicidal depressed adults. Similarly, Sublette et al. (2011) found that TRP levels did not differ in adults with and without a history of suicide attempt; however, KYN levels did differ, suggesting that activation of the KP and neurotoxicity, and not serotonin deficiency, may play a more important role in suicidality. Consistent with this view, our study also found an increase in the KYN/TRP ratio, a marker for IDO activity, which indicates that inflammatory processes play a role in TRP metabolism and depression (Maes et al., 1994; Myint and Kim, 2003). This hypothesis is supported by the recent report of increased CSF QUIN, along with concomitant increases of interleukin (IL)-6 in suicidal individuals compared to healthy controls (Erhardt et al., 2013). In addition, the possible role of inflammatory processes in suicide in our sample can also be inferred by the enhanced significant findings of the KYN/TRP ratio and TRP subsequent to the exclusion of participants treated with psychotropic medications, known to have anti-inflammatory effects (Kostadinov et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014; Obuchowicz et al., 2014).

Despite our peripheral measures, converging evidence suggests that KP activity in the blood parallels its activity in the brain. For example, increased plasma IDO activity is coupled with simultaneous increases of KYN, QUIN, and KA in the CSF subsequent to interferon-alpha (IFN-α) treatment (Raison et al., 2009). Further, preclinical data have specifically linked peripheral and central IDO activation to depressive-like behaviors (Henry et al., 2008; Moreau et al., 2008), while peripheral inhibition of IDO blocked the central transcription of IDO in the brain and the development of depressive-like symptoms following immunological stimulation (O'Connor et al., 2009; Salazar et al., 2012).

One possible pathway that may explain the relation between the KP and suicidality in depressed adolescents may involve neurotoxicity in the reward circuitry, manifesting as anhedonia and known to be associated with suicidality (Gabbay et al., in press). Supporting evidence includes preclinical data documenting that striatal and cortical neurons are particularly vulnerable to 3-HK and 3-HAA toxicity (Okuda et al., 1998; Heyes et al., 2001). Similarly, our laboratory also reported highly significant positive correlations between KYN and 3-HAA and striatal total choline (tCho)—reflecting membrane breakdown—in anhedonic patients (Gabbay et al., 2010b) and associations between IDO (indexed by KYN/TRP) and anhedonia (Gabbay et al., 2012). Relatedly, a recent review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies concluded that dysfunction in fronto-striatal circuitry specifically is involved in suicidal behavior (Zhang et al., 2014). Further, while our combined high-risk suicidal group was not significantly more anhedonic than the non-suicidal adolescents with depression, those who were actively suicidal did exhibit increased anhedonia. Therefore, it is possible that anhedonia may be an acute clinical marker for suicidality in depressed adolescents. Our findings also demonstrated that with respect to KP activation, depressed adolescents with a history of suicide attempt were similar to those who were acutely suicidal even though behaviorally, they were not as clinically depressed, anhedonic, or suicidal. This finding is consistent with the clinical phenomenon that depressed individuals with past attempts are at the highest risk for suicide despite their communication that they are not experiencing suicidal ideations (Pfeffer et al., 1993; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Brown et al., 2000).

The current study has several limitations. First is the narrow assessment of KP metabolites, in which 3-HK, QUIN, and KA were not assessed (as illustrated in Figure 1). Additionally, other factors affecting the metabolism of TRP were not explored. For example, pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency alters TRP metabolism (Linkswiler et al., 1967), with depletion of vitamin B6 inhibiting the breakdown of KYN and 3-HK and increasing the quantities of these metabolites (Yess et al., 1964). Furthermore, there is a potential methodological confound of quantifying IDO activity using the KYN/TRP ratio. While this is an accepted method of indexing IDO activity, the enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) also metabolizes TRP to KYN (Oxenkrug et al., 2014; Quak et al., 2014). Therefore, the KYN/TRP ratio indirectly measures IDO and TDO activity. Moreover, our analyses of the KP metabolites did not include a multiple comparison correction due to the small sample; however, when medicated patients were excluded, our pairwise comparisons between suicidal and non-suicidal depressed individuals survived a conservative Bonferroni corrected alpha-level of 0.0125 (α = 0.05/4 based on number of metabolites measured), suggesting that despite the small sample size, these effects were likely real. Finally, a fundamental clinical limitation to studies of suicide is the limited ability to ascertain the “true” state of mind during a suicide attempt/self-injurious behavior. In order to minimize this dilemma, acts classified as suicide attempts were all serious.

In summary, our findings imply a possible specific role of the KP in suicidality in depressed adolescents. Findings should be replicated in a larger medication-free sample, while also examining other KP metabolites and cytokines in order to further elucidate the relation between neuroinflammation and neurobiological correlates of adolescent MDD. Identification of biological mechanisms that contribute to disease severity among adolescents is of paramount importance to both identifying and treating those youth that are at increased risk for suicide.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Plasma KYN/TRP (IDO) is increased in suicidal adolescents with MDD.

Plasma TRP is decreased in suicidal adolescents with MDD.

KYN/TRP (IDO) differences were enhanced when medicated adolescents were excluded.

TRP and KYN/TRP (IDO) were similar in acutely and previously suicidal adolescents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (MH095807, MH101479).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author Bradley analyzed data, and wrote and prepared the manuscript. Author Case performed the literature review, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript. Author Khan conducted preliminary analyses and participated in manuscript preparation. Author Ricart conducted preliminary analyses and participated in manuscript preparation. Author Hanna assisted in literature review and table making. Author Alonso assisted in clinical evaluation of patients and consulted on the project. Author Gabbay developed study protocol, evaluated patients, oversaw recruitment, and edited manuscript drafts. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to report for any of the authors on this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kailyn A. L. Bradley, Email: kailyn.bradley@mssm.edu.

Julia A. C. Case, Email: julia.case@mssm.edu.

Omar Khan, Email: omar.khan@mssm.edu.

Thomas Ricart, Email: thomas.ricart@mountsinai.org.

Amira Hanna, Email: amira.hanna@mssm.edu.

Carmen M. Alonso, Email: carmen.alonso@nyumc.org.

Vilma Gabbay, Email: vilma.gabbay@mssm.edu.

REFERENCES

- Almeida-Montes LG, Valles-Sanchez V, Moreno-Aguilar J, Chavez-Balderas RA, Garcia-Marin JA, Cortés Sotres JF, Hheinze-Martin G. Relation of serum cholesterol, lipid, serotonin and tryptophan levels to severity of depression and to suicide attempts. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2000;25:371–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: 2000. text rev. Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Richter C, Linderholm KR, Lim CK, Samuelsson M, Träskman-Bendz L, Guillemin GJ, Erhardt S, Brundin L. A role for inflammatory metabolites as modulators of the glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in depression and suicidality. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2015;43:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M. Psychiatric risk factors of adolescent suicide: a case control study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB. Serum tryptophan ratio and suicidal behavior in adolescents: a prospective study. Psychiatry Research. 2003;119:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curzon G, Bridges PK. Tryptophan metabolism in depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1970;33:698–704. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.33.5.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt S, Lim CK, Linderholm KR, Janelidze S, Lindqvist D, Samuelsson M, Lundberg K, Postolache TT, Träskman-Bendz L, Guillemin GJ, Brundin L. Connecting inflammation with glutamate agonism in suicidality. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:743–752. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Ely BA, Babb J, Liebes L. The possible role of the kynurenine pathway in anhedonia in adolescents. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2012;119:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Johnson AR, Alonso CM, Evans LK, Babb JS, Klein RG. Anhedonia but not irritability is associated with illness severity outcomes in adolescent major depression. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0105. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Klein RG, Guttman LE, Babb JS, Alonso CM, Nishawala M, Katz Y, Gaite MR, Gonzalez CJ. A preliminary study of cytokines in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescents with major depression. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:423–430. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Klein RG, Katz Y, Mendoza S, Guttman LE, Alonso CM, Babb JS, Hirsch GS, Liebes L. The possible role of the kynurenine pathway in adolescent depression with melancholic features. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010a;51:935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Liebes L, Katz Y, Liu S, Mendoza S, Babb JS, Klein RG, Gonen O. The kynurenine pathway in adolescent depression: preliminary findings from a proton MR spectroscopy study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2010b;34:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne A, Hanke M, Himler J, Bailey MT, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP. Minocycline attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation, sickness behavior, and anhedonia. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:15–28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes MP, Ellis RJ, Ryan L, Childers ME, Grant I, Wolfson T, Archibald S, Jernigan TL. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid quinolinic acid levels are associated with region-specific cerebral volume loss in HIV infection. Brain. 2001;124:1033–1042. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes MP, Saito K, Crowley JS, Davis LE, Demitrack MA, Der M, Dilling LA, Elia J, Kruesi MJP, Lackner A, Larsen SA, Lee K, Leonard HL, Markey SP, Martin A, Milstein S, Mouradian MM, Pranzatelli MR, Quearry BJ, Salazar A, Smith M, Strauss SE, Sunderland T, Swedo SW, Tourtellotte WW. Quinolinic acid and kynurenine pathway metabolism in inflammatory and noninflammatory neurological disease. Brain. 1992;115:1249–1273. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinov ID, Delev DP, Murdjeva MA, Kostadinova II. Experimental study on the role of 5-HT2 serotonin receptors in the mechanism of anti-inflammatory and antihyperalgesic action of antidepressant fluoxetine. Folia Medica. 2014;56:43–49. doi: 10.2478/folmed-2014-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeray L, Launay JM, Callebert J, Surget A, Belzung C, Barone PR. Peripheral and cerebral metabolic abnormalities of the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway in a murine model of major depression. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;210:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkswiler H. Biochemical and physiological changes in vitamin B6 deficiency. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1967;20:547–557. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/20.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RP, Zou M, Wang JY, Zhu JJ, Lai JM, Zhou LL, Chen SF, Zhang X, Zhu JH. Paroxetine ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia activation via differential regulation of MAPK signaling. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:47–57. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Scharpé S, Meltzer HY, Okayli G, Bosmans E, D'Hondt P, Vanden Bossche BV, Cosyns P. Increased neopterin and interferon-gamma secretion and lower availability of L-tryptophan in major depression: further evidence for an immune response. Psychiatry Research. 1994;54:143–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Malone KM, Sweeney JA, Brown RP, Linnoila M, Stanley B, Stanley M. Attempted suicide characteristics and cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites in depressed inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:576–586. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau M, André C, O'Connor JC, Dumich SA, Woods JA, Kelley KW, Dantzer R, Lestage J, Castanon N. Inoculation of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin to mice induces an acute episode of sickness behavior followed by chronic depressive-like behavior. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008;22:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint AM, Kim YK. Cytokine-serotonin interaction through IDO: A neurodegeneration hypothesis of depression. Medical Hypotheses. 2003;61:519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JC, Lawson MA, André C, Moreau M, Lestage J, Castanon N, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:511–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowicz E, Bielecka AM, Paul-Samojedny M, Pudełko A, Kowalski J. Imipramine and fluoxetine inhibit LPS-induced activation and affect morphology of microglial cells in the rat glial culture. Pharmacology Reports. 2014;66:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda S, Nishiyama N, Saito H, Katsuki H. 3-Hydroxykynurenine, an endogenous oxidative stress generator, causes neuronal cell death with apoptotic features and region selectivity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70:299–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenkrug G, Turski W, Zgrajka W, Weinstock J, Ruthazer R, Summergrad P. Disturbances of tryptophan metabolism and risk of depression in HCV patients treated with IFN-alpha. Journal of Infectious Diseases & Therapy. 2014;2:131. doi: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, Pastor P, Ghandour RM, Gfroerer JC, Hedden SL, Crosby AE, Visser SN, Schieve LA, Parks SE, Hall JE, Brody D, Simile CM, Thompson WW, Baio J, Avenevoli S, Kogan MD, Huang LN. Mental health surveillance among children-United States, 2005–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Klerman GL, Hurt SW, Kakuma T, Peskin JR, Siefker CA. Suicidal children grow up: rates and psychosocial risk factors for suicide attempts during follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:106–113. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, McBride PA, Anderson GM, Kakuma T, Fensterheim L, Khait V. Peripheral serotonin measures in prepubertal psychiatric inpatients and normal children: associations with suicidal behavior and its risk factors. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:568–577. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quade D. Rank analysis of covariance. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1967;62:1187–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Quak J, Doornbos B, Roest AM, Duivis HE, Vogelzangs N, Nolen WA, Penninx BW, Kema IP, de Jonge P. Does tryptophan degradation along the kynurenine pathway mediate the association between pro-inflammatory immune activity and depressive symptoms? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;45:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Lawson MA, Woolwine BJ, Vogt G, Spivey JR, Saito K, Miller AH. CSF concentrations of brain tryptophan and kynurenines during immune stimulation with IFN-alpha: relationship to CNS immune responses and depression. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;15:393–403. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbach J, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Franke L, Uebelhack R, Blank S, Ahrens B. Peripheral serotonergic markers in acutely suicidal patients. 1. Comparison of serotonergic platelet measures between suicidal individuals, nonsuicidal patients with major depression and healthy subjects. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2007;114:479–487. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A, Gonzalez-Rivera BL, Redus L, Parrott JM, O'Connor JC. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase mediates anhedonia and anxiety-like behaviors caused by peripheral lipopolysaccharide immune challenge. Hormones and Behavior. 2012;62:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sublette ME, Galfalvy HC, Fuchs D, Lapidus M, Grunebaum MF, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, Postolache TT. Plasma kynurenine levels are elevated in suicide attempters with major depressive disorder. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yess N, Price JM, Brown RR, Swan PB, Linkswiler H. Vitamin B6 depletion in man: urinary excretion of tryptophan metabolites. Journal of Nutrition. 1964;84:229–236. doi: 10.1093/jn/84.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Chen Z, Jia Z, Gong Q. Dysfunction of neural circuitry in depressive patients with suicidal behaviors: a review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2014;53:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]