Abstract

BACKGROUND

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is characterized by recurrent pancreatic injury, resulting in inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis. There are currently no drugs limiting pancreatic fibrosis associated with CP, and there is a definite need to fill this void in patient care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pancreatitis was induced in C57/BL6 mice using supraphysiologic doses of cerulein (CR), and apigenin treatment (once daily, 50 μg/mouse by oral gavage) was initiated one week into the recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) protocol. Pancreata were harvested after four weeks of RAP. Immunostaining with fibronectin antibody was used to quantify the extent of pancreatic fibrosis. To assess how apigenin may decrease organ fibrosis, we evaluated the effect of apigenin on the proliferation and apoptosis of human pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) in vitro. Lastly, we assessed apigenin’s effect on gene expression in PSCs stimulated with parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP), a pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediator of pancreatitis, using RT-PCR.

RESULTS

After four weeks of RAP, apigenin significantly reduced the fibrotic response to injury while preserving acinar units. Apigenin inhibited viability and induced apoptosis of PSCs in a time and dose-dependent manner. Lastly, apigenin reduced PTHrP-stimulated increases in the PSC mRNA expression levels of extracellular matrix proteins collagen 1A1 and fibronectin, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, TGF-β, and IL-6.

CONCLUSIONS

These in vivo and in vitro studies provide novel insights regarding apigenin’s mechanism(s) of action in reducing the severity of RAP. Additional preclinical testing of apigenin analogs is warranted to develop a therapeutic agent for patients at risk for CP.

Keywords: Apigenin, Chronic Pancreatitis, Pancreatic stellate cells, Parathyroid hormone-related protein

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive, irreversible disease process characterized by chronic inflammation, glandular necrosis, and fibrosis [1]. With repeated injury, functional pancreatic tissue is replaced with fibrotic scar; and when pancreatic reserve is exhausted, exocrine and endocrine insufficiencies develop [2]. Patients have a poor quality of life and are burdened by chronic abdominal pain, impaired digestion, malnutrition, anorexia, diabetes, and disease-related complications such as pseudocyst formation [3]. CP also increases a patient’s risk of developing pancreatic cancer [4].

Accumulating genetic, clinical and experimental evidence support the hypothesis that CP is the result of multiple episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) [5–7]. The risk factors that are associated with the development of CP include alcohol consumption, smoking, nutritional factors, hereditary pre-disposition, efferent duct obstruction, immunologic factors, and metabolic disease [2]. Irrespective of the etiology, pancreatitis involves a common cascade of events: acinar cell injury causing aberrant zymogen secretion and premature activation, tissue auto-digestion, generation of an inflammatory response, focal necrosis, and fibrosis [5, 6, 8]. With recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, the pancreas is unable to adequately recover from the repeated injury, perpetuating a microenvironment of chronic inflammation and irreversible fibrosis [5, 6].

Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are responsible for generating the characteristic glandular scarring of CP [9]. Pancreatic injury promotes the activation of PSCs, which rapidly proliferate, migrate to sites of injury, synthesize and remodel extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, and secrete cytokines and growth factors, further amplifying the immune response [9, 10]. Parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP) has been identified as a pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediator of acute pancreatitis (AP) and CP [11, 12]. PSCs not only express the G-protein coupled receptor for PTHrP, but also have been shown to secrete the PTHrP protein in response to injury [11–14].

Currently, treatment options for CP are limited to supportive care and symptom palliation. Patients must adapt to a lifestyle involving chronic pain management, digestive enzyme replacement, vitamin supplementation, and glucose control [3]. Medical management often fails with advanced disease, and patients are offered more invasive interventions, ranging from endoscopic stenting of strictures to surgical bypass procedures or even total pancreatectomy [15]. There is a definite need to develop pharmacologic agents directed at the pathogenesis of CP, reducing pancreatic damage, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) is a natural compound with low intrinsic toxicity, found in various fruits, vegetables, herbs and beverages like chamomile tea [16]. Herein, we report how apigenin protects the pancreas from repeated pancreatic injury, and therefore slows the development of CP. This is accomplished, in part, by apigenin: 1) inhibiting PSC proliferation; 2) inducing PSC apoptosis; and 3) and minimizing PTHrP-mediated PSC response to injury. Our data suggest that apigenin and/or apigenin-like compounds could be developed into novel pharmacological inhibitors of RAP progression in patients at risk for CP.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

Cerulein was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Apigenin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The human parathyroid related protein (1–36) was purchased from Polypeptide Laboratories (San Diego, CA). The following reagents were purchased from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA): target retrieval solution, antibody diluent, liquid DAB and substrate chromogen system. Fibronectin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). The following products were purchased from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, CA): biotinylated secondary antibody, VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit, and VectaMount. The Hematoxylin 7211 counterstain was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Kalamazoo, MI). Cell culture reagents were utilized from the following companies: DMEM (VWR, Randor, PA); collagen from calf skin, penicillin, streptomycin, amphotericin, and gentamicin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); insulin-transferrin-selenium-ethanolamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY); non-essential amino acids (Sigma); and fetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonza, Walkersville, MD).

2.2 Recurrent-Acute Pancreatitis Model of Chronic Pancreatitis

All animal studies were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International. We utilized a well-established model of recurrent pancreatic injury to induce CP. Repeated administration of the cholecystokinin (CCK) analog, cerulein (CR), leads to hyperstimulation of pancreatic acinar cells, aberrant zymogen secretion and premature activation [17, 18]. Over time, the repeated cycles of injury and inflammation result in the histological and pathophysiological characteristics of CP [8, 17]. Male and female C57/BL6 mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN; and The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), 6–8 weeks old, were randomly divided into two groups and received either five hourly intraperitoneal (IP) injections of CR (50 μg/kg mouse weight) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) three days per week (MWF) for a total of 4 weeks (Fig. 1). The randomization was performed without regard to sex.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of translational RAP model in mice.

2.3 Apigenin Treatment

After one week following the RAP protocol, mice in both the CR and PBS groups were further subdivided into two groups and treated by oral gavage with either apigenin (50 μg) or vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose (MC) + 0.025% Tween 20 in ddH20) once daily, six days per week for the remaining three weeks of RAP induction (Fig. 1). At the end of four weeks, pancreata were harvested and processed as described below. All treatments and evaluation of pancreatic tissue were performed without regard to sex.

2.4 Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Pancreata were fixed in 10% formalin for 72 h at 4°C, embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned (5 μm), and transferred to glass slides. Prior to immunostaining, the slides were de-paraffinized with xylene, rehydrated through an ethanol gradient, and washed with ddH20 for 3 min x3. Heat-mediated antigen retrieval was performed by incubating slides in citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.1) for 30 min at 97°C. The slides were washed with ddH20 for 5 min x2. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at 20°C. Non-specific antibody binding was blocked using a solution of 5% rabbit serum and 1% BSA in PBS for 3 h at 20°C. Incubation with the primary antibody (rabbit anti-fibronectin, 1:600 in antibody diluent) was preformed overnight (~16 h) at 4°C in a humidity chamber.

The slides were washed in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 5 min x2 followed by washes with PBS 5 min x2. Incubation with secondary antibody (biotinylated rabbit anti-goat, 1:400 in antibody diluent) was completed for 30 min at 20°C in a humidity chamber. This was followed by the PBS-T and PBS washes as described previously. Fibronectin immunoreactivity was visualized using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit and color development was achieved with DAB. The slides were washed with ddH20 for 3 min x2 and counterstained with Hematoxylin 7211. Finally, the slides were dehydrated with an ascending graded series of ethanol followed by xylene. Cover slips were adhered with VectaMount.

2.5 Image Analysis

Ten non-overlapping images of each pancreas (400x) were taken using a BX51 microscope and DP71 Olympus digital camera. The images were analyzed using NIH free-ware Image Processing and Analysis in Java (ImageJ) 1.46r along with a color deconvolution plug-in [19], which enabled quantification of the percentage of fibronectin staining (brown color) per 400X field. The region of interest (ROI) was set as the entire 400x image. The sequence of commands used included: background subtraction; automatic adjustment of brightness/color; color deconvolution using the H DAB vector and selection of the brown channel; minimal thresholding; and automated measurement of mean area of brown color within the ROI.

2.6 Isolation and Culture of Human Pancreatic Stellate Cells (PSCs)

At the time of surgical resection, discarded human pancreatic tissue was collected under an IRB-approved protocol. The PSCs were isolated using an outgrowth method [20, 21] and used without regard to sex. Briefly, fresh pancreatic tissue was minced into 0.5 mm3 pieces and placed into a T-25 collagen-coated flask (15 μg/ml) containing 3 ml of DMEM media supplemented with penicillin 200 U/ml, streptomycin 200 μg/ml, amphotericin B 0.25 μg/ml and gentamicin 50 μg/ml, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium-ethanolamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 10% FBS. The cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 3–4 weeks in culture, the presence of PSCs was confirmed by immunostaining for vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin, and glial fibrillar acidic protein. The primary PSCs cultures were immortalized by transducing the cells with lentivirus containing SV40 Large T antigen and human telomerase (plasmids #12245 and #12246, Addgene, Cambridge, MA).

2.7 Cell Proliferation Assays

To quantify cell proliferation over time, PSCs were plated in quadruplicate in a 12-well plate (1.5 × 105 cells/well) containing DMEM with 10% FBS. The next day, the media was changed to DMEM with 1% FBS, and the cells were treated with either apigenin (30 μM) or vehicle (DMSO) for 24, 48, and 78 hours. At each time point, the cells were recovered from the wells using trypsin, and the number of cells per well were quantified with a Coulter Z1 Particle Counter (Beckman, Hialeah, FL).

To evaluate cell viability relative to the dose of apigenin, PSCs were seeded in sextuplicate in a 96-well plate (3×103 cells/well) containing DMEM with 10% FBS. The next day, the media was changed to DMEM with 1% FBS, and the cells were treated with increasing doses of apigenin (0–50 μM) for 48 h. Then, the alamarBlue® reagent (DAL1025, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the cell culture media (1/10th the well volume) for a 4 h incubation at 37°C, protected from light. Metabolically active cells convert resazurin to the highly fluorescent product resorufin, which was measured at excitation/emission wavelengths of 544/590 nm by a SpectraMax M2 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The average fluorescent reading from media-only wells was subtracted from the data output, accounting for background fluorescence. Apigenin did not interfere with the assay as it is weakly fluorescent in aqueous solutions [22].

2.8 Cell Death Assay

PSCs were seeded in triplicate in a 96-well plate (8×103 cells/well) containing DMEM with 10% FBS. The next day, the media was changed to DMEM with 1% FBS, and the cells were treated with apigenin for various time points and concentrations (0–50 μM for 14–16 h) using serial dilutions. In-well cell lysis and the Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS assay (Version 11.0, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol, which involves antibodies binding to mono- and oligonucleosomes that are specific to apoptosis rather than necrosis. Untreated cells served as the negative control, and the kit included a DNA-histone complex as a positive control. Absorbance output was measured at 405 nm using an ELx808 Automated Microplate Reader (Bio-TEK Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Apigenin’s two intrinsic absorbance bands, Band I (300–390 nm) and Band II (250–280 nm)[22], lie outside the spectra measured in this assay [22].

2.9 RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using an RNAqueous® kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were quantified using a Nanodrop Technologies spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE). Total RNA quality was assessed with an RNA Nano chip and Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA). Complimentary DNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). RT-PCR was performed with the Faststart Universal SYBR green Master Mix (Roche), the primers listed in Table 1, and the ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies). The threshold cycle (CT) values for each gene target were normalized to 18S levels. Relative expression level was calculated using: n-fold change = 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT represents CT (target sample) − CT (control).

Table 1.

List of primers used in SYBR-green RT-PCR.

| Primer (Abbrev.) | Species | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen type 1α1 (COL1A1) | Human | GGCAGCCTTCCTGATTTCTG | CTTGGCAAAACTGCACCTTCA |

| Fibronectin (FN) | Human | ATGGTGTCAGATACCAGTGCTACTG | TCGACAGGACCACTTGAGCTT |

| Transforming Growth Factor, Beta 1 (TGF-β1) | Human | GCACGTGGAGCTGTACCAGAA | CTGAGGTATCGCCAGGAATTG |

| Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) | Human | GGGCGTGAACCTCACCAGTA | TCATTGCCGGCGCATT |

| Interleukin 6 (IL-6) | Human | ATGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGCG | CCCCAGGGAGAAGGCAAC |

| Interleukin 8 (IL-8) | Human | GGCAGCCTTCCTGATTTCTG | CTTGGCAAAACTGCACCTTCA |

2.10 Statistical Analysis

For the cell proliferation and cell death assays, dose-response curves were generated by plotting fluorescence or absorbance versus log [apigenin]. A best-fit curve was created using nonlinear regression (GraphPad Prism5, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA), and the IC50 or EC50 determined from the graph. SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used to conduct statistical analysis, which included One-way ANOVA and post-hoc analysis with Tukey-Kramer Multiple Comparisons test. Significance was set at p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Apigenin reduced stromal fibrosis in an in vivo model of RAP

To determine whether apigenin can inhibit the development of CP, we used a well-characterized mouse model of RAP, which has been shown to produce the morphological, biochemical and pathophysiological features of humans with CP [8, 17]. Mice were treated with supraoptimal doses of CR, a CCK1 receptor agonist. Consecutive hourly injections of CR causes hyper-stimulation of acinar cells; proteases like trypsinogen accumulate within the acini and activate prematurely, causing auto-digestion, tissue injury, and generation of an acute inflammatory response [23, 24].

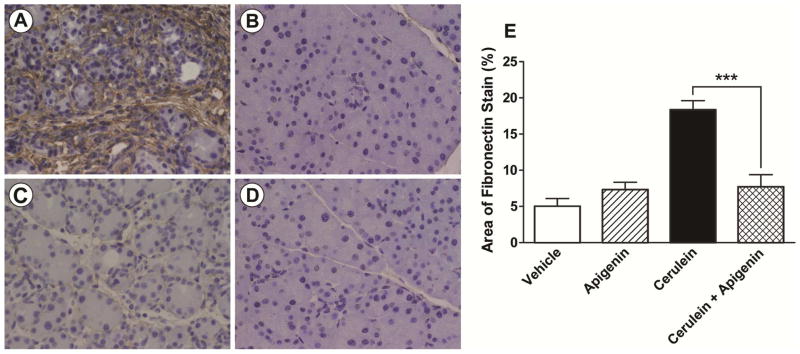

To model a clinically relevant situation, we initiated the RAP protocol one week prior to apigenin therapy (Fig. 1). Apigenin (50 μg, once daily, 6d/wk, by oral gavage) was administered the remaining 3 weeks of RAP. A total of three independent experiments were performed. Supraoptimal doses of CR induced pancreatic injury characteristic of CP (Fig. 2A): the acini were atrophic and heterogeneous in size and shape; the interstitial space was increased by edema, inflammatory infiltrate, and stromal fibrosis, which was stained brown by fibronectin IHC. This morphological damage induced by our model is consistent with that produced by others following the same protocol and time period [25].

FIGURE 2. Apigenin reduced fibrosis in a pre-clinical model of RAP in mice.

Representative 400x images of slides stained for fibronectin by IHC, and counter-stained with hematoxylin are presented in A-D). Each study group had 5–6 mice. Apigenin’s vehicle was 0.5% methylcellulose (MC) + 0.025% Tween 20 in ddH20, and the vehicle for CR was phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The treatment groups included: A) CR (+ apigenin’s vehicle); B) both Vehicles; C) CR + Apigenin; and D) Apigenin (+ CR’s vehicle). The percent area of brown fibronectin stain was quantified using computational ImageJ analysis with results graphed in E). The animal experiment was repeated in triplicate, and *** indicates a significant p-value < 0.001.

The histologic appearance of normal pancreatic architecture was illustrated in the control mice treated with vehicle (PBS and 0.5% MC + 0.025% Tween 20 in ddH20) (Fig. 2B). The pancreatic histology of mice treated with apigenin alone was comparable to that of the vehicle group (Fig. 2D). During CR-induced RAP, apigenin treatment reduced the severity of pancreatic injury: preserving acinar units; decreasing interstitial edema; reducing inflammatory infiltrate; and limiting peri-acinar and peri-lobular fibrosis (Fig. 2C). Quantification of CR-induced fibrosis was performed by immunohistochemical staining for fibronectin. Image analysis of ten non-overlapping, representative fields of each pancreas confirmed that fibronectin protein was significantly reduced by 58% (p < 0.001) in mice treated with apigenin during RAP (Fig 2E).

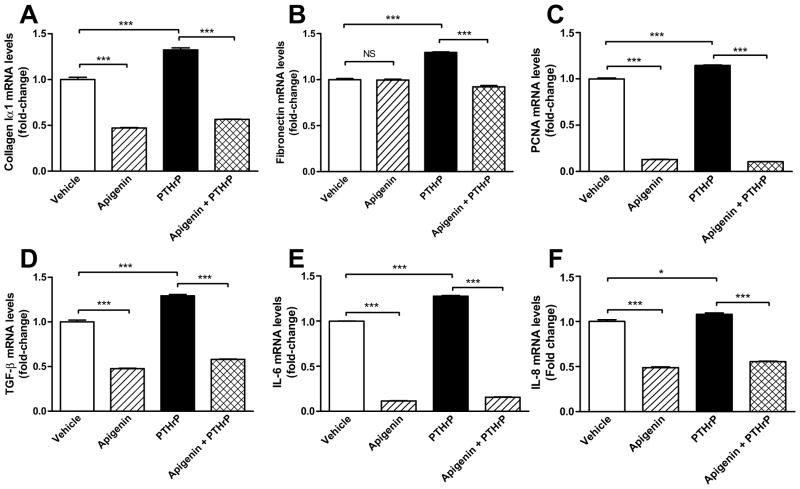

3.2 Apigenin inhibited PSC cell viability in a time and dose-dependent manner

Apigenin has been shown to possess multiple beneficial properties, including anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory activity [16]. Therefore, we hypothesized that apigenin’s anti fibrotic effect seen in our preclinical animal model, is due to the growth inhibition of PSCs, the cells which are responsible for the dysregulated ECM deposition and remodeling [9]. To test our hypothesis, we performed an in vitro proliferation assay. PSCs were treated with a single dose of apigenin (30 μM) or vehicle (DMSO), and the cells were counted at three different time points. Compared to vehicle, apigenin treatment inhibited PSC growth over the time (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3. Apigenin inhibited PSC viability in a time and dose-dependent manner.

A) PSCs were treated with apigenin (30 μM, square) or vehicle (DMSO, triangle) over the time points indicated. Cell proliferation was measured by cell counting with a Coulter counter, and each condition graphed represents a replicate of four. B) PSCs were treated with apigenin at various doses for 48 h, and a dose-response curve was generated using the alamarBlue® cell viability assay. The graph shown is a single assay. The IC50 (18.6 ± 1.6 μM) is derived from a total of 10 independent assays [26].

A dose-response curve was generated to determine apigenin’s IC50, which represented the concentration at which apigenin induces 50% inhibition of PSC viability. PSCs were treated with escalating doses of apigenin for a set time period of 48 h, and cell viability was assessed using the alamarBlue® assay. PSC cell viability was found to decrease with increasing concentrations of apigenin (Fig. 3B). As we have previously reported, the IC50 of apigenin was confirmed as 18.6 ± 1.6 μM (mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)) based on data from ten independent assays [26].

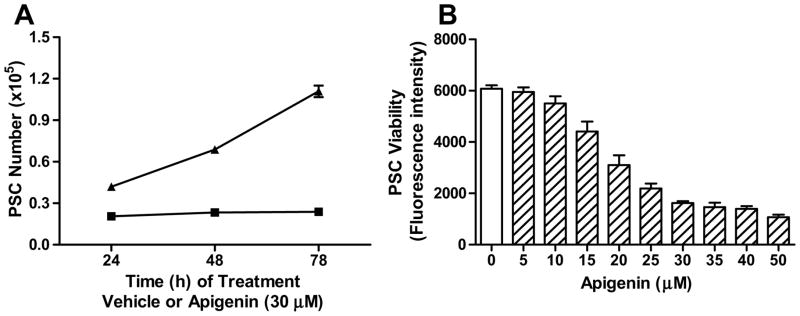

3.3 Apigenin induced apoptosis in a time and dose-dependent manner

PSCs in CP are not only metabolically active with a high mitotic index, but they display limited cell death [9], further perpetuating the fibrotic response to repeated pancreatic injury. The Cell Death Detection ELISA assay was utilized to evaluate how apigenin induces PSC apoptosis over time. PSCs were treated with a single dose of apigenin (50 μM), and their apoptosis was assessed at several time points. Significant cell death was induced beyond 2 h and increased with incubation time up to 6 h (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4. Apigenin induced PSC apoptosis in a time and dose-dependent manner.

A) PSCs were treated with apigenin (50 μM) over the time points indicated, and the Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS assay was performed. B) PSC were treated with apigenin at various doses for 14–16 h. Apoptosis was quantified as in A), and the dose-response curve was generated. The graph represents a single assay, and apigenin’s EC50 (24.5 ± 2.5 μM) is derived from a total of 7 independent assays [26].

PSCs were then treated with increasing doses of apigenin for a fixed time of 14–16 h. The dose-response studies showed that apigenin induced PSC apoptosis in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 4B). We have previously reported the EC50 of apigenin as 24.5 ± 2.5 μM, which represented the concentration that yielded half the maximal amount of cell death [26]. The EC50 was confirmed by seven independent assays.

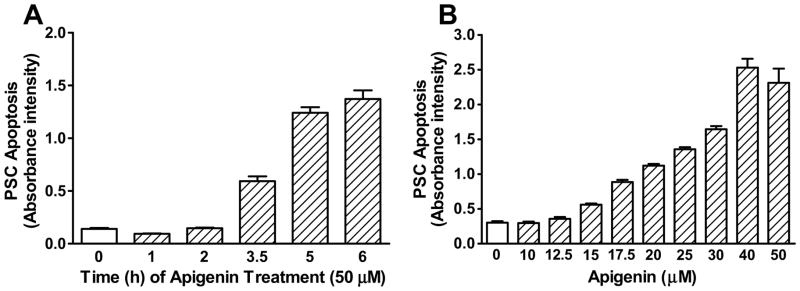

3.4 Apigenin minimized PTHrP-induced ECM synthesis, PSC proliferation and inflammation

PTHrP has been identified as a pro-fibrogenic and pro-inflammatory mediator of pancreatitis [11, 12]. We stimulated PSCs with PTHrP (10−7 M for 12 h). PSCs were pretreated with apigenin (50 μM for 1 h) or vehicle (DMSO). Using RT-PCR, we investigated the mRNA expression of ECM proteins collagen 1A1 and fibronectin, cell proliferation marker PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in PSC cells at 12 h. Apigenin significantly reduced PSC transcriptional response to PTHrP in all of the factors evaluated (p < 0.001), except, in the case of IL-8 mRNA, where the reduction caused by apigenin is independent of PTHrP. Furthermore, apigenin decreased the basal mRNA expression of all proteins assayed, with the exception of fibronectin (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5. Apigenin decreased PTHrP-induced ECM synthesis, PSC proliferation and inflammation.

PSC were pretreated with apigenin (50 μM) or vehicle (DMSO) for 1 h, followed by stimulation with PTHrP (10−7 M) for 12 h. Total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR performed to determine mRNA expression of A) collagen 1A1, B) fibronectin, C) PCNA, D) TGF-β, E) IL-6, and F) IL-8. Fold change was calculated relative to vehicle treatment. The graphs depicted are the combined results of two independent experiments. Significant p-values are indicated as * (p<0.05) and *** as p < 0.001. Non-significant p-values (<0.05) are labelled as NS.

4. DISCUSSION

Chronic pancreatitis is a necro-inflammatory disease where functional parenchymal is replaced with scar. According to the RAP hypothesis, CP is the result of repeated episodes of AP [5–7]. The cascade of events is initiated by acinar cell injury. Intracellular zymogens become prematurely activated, and pancreatic auto-digestion generates a pro- inflammatory mediators such as TGF-β [27] and PTHrP [11, 12]. PSCs play a central role in the normal physiologic response to injury, secreting and remodeling the ECM [9]. Patients can recover from a bout of AP; however, recurrent insults amplify the degree of injury and inflammation, interrupt the repair process, and promote the progression to CP. Since CP has no cure, there is a need to develop therapies, such as apigenin, to directly inhibit the progression to CP.

We show that daily administration of apigenin, 50 μg/mouse (≈ 2.5 mg/kg) by oral gavage, significantly limited stromal fibrosis while preserving acinar units (Fig. 2). When comparing mice subjected to CR-induced RAP, apigenin treatment reduced fibronectin immunohistochemical staining by 58%. We have previously used the RAP model to evaluate apigenin’s anti-fibrotic effect at a lower dose (10 μg/mouse, ≈ 0.5 mg/kg, by oral gavage 5 d/wk), which resulted in a 37% reduction in fibronectin staining [26]. Thus, the higher dose of apigenin produced a greater decrease in stromal fibrosis.

Lampropoulos et al. evaluated the application of apigenin in AP [28]. Rats underwent bilio-pancreatic duct ligation (PDL) followed by a single 5 mg dose of apigenin administered orally. After 72 h, apigenin treatment limited pancreatic tissue edema, necrosis, inflammatory infiltrate, and myeloperoxidase activity [28]. Since CP is the result of RAP, our findings are consistent in that apigenin preserves pancreatic architecture.

In our pre-clinical mouse model of CP, we thought apigenin treatment may produce this protected phenotype by altering the activity of PSCs, which are responsible for generating the fibrotic response to pancreatic injury. In CP, there is shift in homeostasis, favoring PSC activation over quiescence. Activated PSC are identified by α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression and a myofibroblastic phenotype: actively proliferating with limited apoptosis; producing and remodeling ECM structural components such as fibronectin and collagen; and promoting inflammation by generating signaling molecules such as TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 [9, 29, 30].

We found that apigenin reduced cell viability (Fig. 3) and promoted apoptosis (Fig. 4) of PSCs in a time and dose-dependent manner. A similar study was conducted with hepatic stellate cell (HSCs), which mediate the fibrotic response of the liver; it revealed that HSC proliferation was inhibited with escalating doses of apigenin [31]. Thus, apigenin acts as an anti-fibrotic agent by directly targeting the cells responsible for the aberrant deposition of ECM.

In human CP tissues, immunostaining for PTHrP confirmed in vitro studies that found PTHrP expression to be up-regulated in pancreatitis, resulting in an amplification of the fibrotic and inflammatory response to pancreatic injury [11, 12]. PSCs, acinar and islet of Langerhans cells all express the PTHrP cell-surface receptor, PTH1R [11, 14, 32]. Falzon et al reported that primary and immortalized PSCs responded to PTHrP by increasing mRNA levels of ECM proteins pro-collagen 1 and fibronectin [11].

We have shown that apigenin diminished PSC response to the pro-inflammatory mediator PTHrP by significantly reducing mRNA transcripts of collagen 1A1 and fibronectin (Fig. 5A–B), corresponding to our in vivo study findings. Since apigenin decreased PCNA levels, the compound’s anti-proliferative activity may be, in part, due to PTHrP inhibition (Fig. 5C). Lastly, apigenin reduced mRNA levels of proinflammatory growth factor TGF-β and cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 (Fig. 5D–F). The level of IL-6 has been shown to correspond with the degree of injury in CP [33–35], emphasizing the importance of apigenin regulating both the inflammatory and fibrotic response to minimize the severity of pancreatic damage.

These findings reinforced Falzon’s studies, where PTHrP knock-out mice treated with CR or PDL decreased PSC activation (i.e., less α-SMA positively stained cells); reduced Sirius red staining of pancreatic fibrosis and primary PSC pro-collagen 1 mRNA levels; minimized IL-6 synthesis; and protected the pancreas from histologic damage [12]. Interestingly, apigenin pretreatment reset the threshold for basal transcriptional activity of an ECM protein, signaling molecules and cytokines involved in CP, but not for fibronectin (Fig 5B). Since only a single 12 h time point was analyzed, a time course study may reveal a later time when basal fibronectin expression may be decreased.

Apigenin-like compounds have the potential to be used in high risk patients with a severe bout of AP and/or risk factors for recurrent pancreatitis (i.e. alcoholism, hypertriglyceridemia, structural or genetic anomalies, etc.) to reduce the likelihood of RAP progression to CP. Even though there are abundant dietary sources of this natural compound with low intrinsic toxicity, apigenin’s clinical application is limited by its poor bioavailability, aqueous solubility, and metabolic instability. We have worked with medicinal chemists to develop novel apigenin analogs with enhanced potency in vitro, improved solubility, and comparable anti-fibrotic effects in a proof-of-concept study [26].

Our future studies will involve elucidating molecular mechanisms by which apigenin protects acinar cells from pancreatic injury. The results from our pre-clinical animal model can be strengthened by incorporating additional models of CP such as duct ligation, alcohol feeding, or genetically modified mice [17]. It would be interesting to see how effective apigenin would be when pancreatic damage is induced over a longer time period (>1 wk) prior to initiating treatment. The anti-proliferative and proapoptotic activity of apigenin could be further defined by studying signaling pathways involved in cell cycle arrest and cell death pathway activation. Before clinical trials, additional testing must be performed to evaluate apigenin’s pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicology profile. The results from our in vitro studies as well as the translational animal model of CP support further development of apigenin analogs as a potential therapeutic in RAP.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, CP is a non-curable, progressive disease process due to repeated pancreatic injury. There are currently no drugs targeting the pathogenesis of CP. Our overall objective was to fill this void in patient care by developing a pharmacologic agent for the treatment of RAP, thereby limiting progression to CP. We have identified apigenin as a promising lead compound for further drug development. In our preclinical animal model of RAP, apigenin significantly reduced stromal fibrosis while protecting the pancreas from histologic damage. Apigenin acts as an anti-fibrotic agent by inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis of PSC, which generate the irreversible scarring that replaces functional pancreatic tissue In CP. This, in part, is mediated through apigenin limiting PSC response to PTHrP, a pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediator of pancreatitis. These findings support further development of apigenin and its new analogs as a therapeutic in RAP.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH P01 DK035608 (MRH), K08 CA125209 (CC), and T32 DK763920 (AAM and LJP, PI: MRH). Portions of this work were presented at the 2014 and 2015 Academic Surgical Congresses. We appreciate the work of Eileen Figueroa, Karen Martin, and Steve Schuenke within the Dept. of Surgery for their assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in the article.

Author Contributions: MRH and CC obtained funding. MRH, CC, MF, JZ, and AAM contributed to the conception and/or design of this study. AAM, LJP, and VB conducted the experiments. AAM and HS performed data analysis. AAM, MRH and CC wrote and/or revised the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kloppel G. Pathology of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic pain. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsmark CE. Management of chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1282. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis: new insights into acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1999;45:317. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider A, Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis: a model for inflammatory diseases of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:347. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comfort MW, Gambill EE, Baggenstoss AH. Chronic relapsing pancreatitis; a study of 29 cases without associated disease of the biliary or gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1946;6:376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Burton FR, Presti ME, et al. Repetitive self-limited acute pancreatitis induces pancreatic fibrogenesis in the mouse. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:665. doi: 10.1023/a:1005423122127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erkan M, Adler G, Apte MV, et al. StellaTUM: current consensus and discussion on pancreatic stellate cell research. Gut. 2012;61:172. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apte M, Pirola R, Wilson J. The fibrosis of chronic pancreatitis: new insights into the role of pancreatic stellate cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2711. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia V, Kim SO, Aronson JF, et al. Role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic response associated with acute pancreatitis. Regul Pept. 2012;175:49. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatia V, Rastellini C, Han S, et al. Acinar Cell-Specific Knockout of the Pthrp Gene Decreases the Pro-inflammatory and Pro-fibrotic Response in Pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00428.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannstadt M, Juppner H, Gardella TJ. Receptors for PTH and PTHrP: their biological importance and functional properties. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F665. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.5.F665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasavada RC, Cavaliere C, D’Ercole AJ, et al. Overexpression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pancreatic islets of transgenic mice causes islet hyperplasia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypoglycemia. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shukla S, Gupta S. Apigenin: a promising molecule for cancer prevention. Pharm Res. 2010;27:962. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghdassi AA, Mayerle J, Christochowitz S, et al. Animal models for investigating chronic pancreatitis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2011;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampel M, Kern HF. Acute interstitial pancreatitis in the rat induced by excessive doses of a pancreatic secretagogue. Virchows Arch A Path Anat and Histol. 1977;373:97. doi: 10.1007/BF00432156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruifrok AC, Johnston DA. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2001;23:291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apte MV, Haber PS, Applegate TL, et al. Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture. Gut. 1998;43:128. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachem MG, Schneider E, Gross H, et al. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:421. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park HR, Daun Y, Park JK, et al. Spectroscopic properties of flavonoids in various aqueous-organic solvent mixtures. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2013;34:211. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luthen R, Owen RL, Sarbia M, et al. Premature trypsinogen activation during cerulein pancreatitis in rats occurs inside pancreatic acinar cells. Pancreas. 1998;17:38. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi H, Kimura T, Mimura K, et al. Activation of proteases in cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1989;4:565. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X, Cao Y, Yang W, et al. BMP2 inhibits TGF-beta-induced pancreatic stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix formation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G804. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00306.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, Mrazek AA, Wang X, et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of novel apigenin analogues that suppress pancreatic stellate cell proliferation in vitro and associated pancreatic fibrosis in vivo. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:3393. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rane SG, Lee JH, Lin HM. Transforming growth factor-beta pathway: role in pancreas development and pancreatic disease. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2006;17:107. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampropoulos P, Lambropoulou M, Papalois A, et al. The role of apigenin in an experimental model of acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res. 2013;183:129. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masamune A, Watanabe T, Kikuta K, et al. Roles of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S48. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mews P, Phillips P, Fahmy R, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells respond to inflammatory cytokines: potential role in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;50:535. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, Zhang JP, Ji HT, et al. Effect of six flavonoids on proliferation of hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2000;21:253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cebrian A, Garcia-Ocana A, Takane KK, et al. Overexpression of parathyroid hormone-related protein inhibits pancreatic beta-cell death in vivo and in vitro. Diabetes. 2002;51:3003. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesina M, Wormann SM, Neuhofer P, et al. Interleukin-6 in inflammatory and malignant diseases of the pancreas. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:80. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mroczko B, Groblewska M, Gryko M, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of serum interleukin 6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in the differentiation between pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24:256. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talar-Wojnarowska R, Gasiorowska A, Smolarz B, et al. Clinical significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene polymorphism and IL-6 serum level in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:683. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0390-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]