Abstract

Gold nanoparticles functionalized with biologically-compatible layers may achieve stable drug release while avoiding adverse effects in cancer treatment. We study cisplatin and paclitaxel release from gold cores functionalized with hexadecanethiol (TL) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) to form two-layer nanoparticles, or TL, PC, and high density lipoprotein (HDL) to form three-layer nanoparticles. Drug release was monitored for 14 days to assess long term effects of the core surface modifications on release kinetics. Release profiles were fitted to previously developed kinetic models to differentiate possible release mechanisms. The hydrophilic drug (cisplatin) showed an initial (5-hr.) burst, followed by a steady release over 14 days. The hydrophobic drug (paclitaxel) showed a steady release over the same time period. Two layer nanoparticles released 64.0 ± 2.5% of cisplatin and 22.3 ± 1.5% of paclitaxel, while three layer nanoparticles released the entire encapsulated drug. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model best described each release scenario, while the simplified Higuchi model also adequately described paclitaxel release from the two layer formulation. We conclude that functionalization of gold nanoparticles with a combination of TL and PC may help to modulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release kinetics, while the addition of HDL may enhance long term release of hydrophobic drug.

Keywords: Nanotherapy, cisplatin, paclitaxel, drug release kinetics, drug release modeling

INTRODUCTION

Tumor chemotherapeutic response can be significantly affected by drug physiochemical properties, such as water solubility and bioavailability, as well as intrinsic and physiologic resistance by the tumor tissue itself. Two commonly utilized chemotherapeutics in cancer treatment are cisplatin and paclitaxel [1]. Cisplatin inhibits cell proliferation through multiple mechanisms, including: binding with DNA to form intra-stand adducts causing changes in DNA conformation, promoting mitochondrial damage leading to diminished energy production, altering cellular transport mechanisms, and decreasing ATPase activity within the cells [2,3]. Paclitaxel enhances tubulin polymerization to stable microtubules and stabilizes them against depolymerization, which results in mitotic arrest [4]. While both drugs are effective, they are known to possess adverse reaction profiles. Cisplatin induces renal toxicity caused by its activation within proximal and distal tubules, neurotoxicity by damaging Schwann cells of the myelin sheath, and tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) which results in abnormal metabolic and electrolyte profiles [2]. Paclitaxel has shown dose-limiting hematological toxicity (e.g. neutropenia) and sensory neurotoxicity, along with other adverse non-hematological toxicities including arthralgia, myalgia, and fluid retention [5]. In addition to adverse profiles, the poor water solubility and low bioavailability of paclitaxel have hampered its clinical use. The drug is administered in a solubilized form, Cremophor EL, to overcome minimal water solubility; while the castor oil used to solubilize the drug enhances bioavailability, it is known to induce histamine release resulting in hypersensitivity reactions in some patients [6,7].

In order to enhance tumor response while minimizing systemic toxicity, a variety of drugs have been encapsulated in organic or inorganic nanoparticles, ranging in size from 1 to 100 nm. The rate of drug release is dependent upon the physiochemical properties of the drug, attachment strength between drug molecules and the nanoparticle surface, and surface modifications used in the synthesis process. Gold nanoparticles, in particular, have been utilized as agents for drug delivery as well as in thermal therapy, in vivo imaging, and in radio-sensitization for both pre-clinical and clinical purposes [8]. Through nanoparticle functionalization, drug release may be modulated to ensure sufficient time for nanoparticles to localize in the tumor or to release drug at specific locations (e.g., hypoxic regions) within the tumor microenvironment [9]. For example, the addition of surfactant poly-(ethylene)-glycol (PEG) is known to escalate nanoparticle circulation time by one to two orders of magnitude compared to freely circulating drugs [10], providing additional time for nanoparticles to localize in the solid tumor tissue. Surface modifications must also ensure that nanoparticles can successfully travel throughout systemic circulation to the tumor, extravasate from the intratumoral capillaries, and diffuse throughout the tissue to reach malignant cells [11]. This can be a challenge as nanoparticles administered in vivo are often sequestered and removed from systemic circulation by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) [12].

The heterogeneous cell cycling patterns typically found in tumors ideally require nanoparticle accumulation with a sustained drug release. Paclitaxel-loaded gold nanoparticles have been utilized with this goal in mind while aiming for decreased toxicity and lowered chemoresistance [13,14]. Studies have shown that highly stable PEG-coated gold nanoparticles exhibit a biphasic paclitaxel release pattern with an initial burst followed by a slower release over the next 120 hours [15]. Cisplatin-loaded gold nanoparticles show similar release patterns [16–23]. “Smart-sensing” pH-sensitive nanoparticles have been developed that release cisplatin in specific environments, such as the acidic microenvironment of the tumor or within the cellular endosome once cellular internalization has occurred [23]. Recently, controlled release of cisplatin from magnetic nanoparticles has also been evaluated [24,25].

In this study, we examine the release profiles of cisplatin and paclitaxel from novel two and three layer gold nanoparticles for the purpose of aiding the development of gold-based nanotherapeutics [26]. Two layer gold nanoparticles were synthesized by adding hexadecanethiol (TL) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) to the outside of gold cores. The addition of PC to the outer layer of TL creates a hydrophobic region, similar to the lipid bilayer found on liposomes, which can be utilized for loading hydrophobic drugs. For the three layer gold nanoparticles, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) was added to the two layer nanoparticles for the purpose of improving tumor and liver targeting. For both two and three layer gold nanoparticles, paclitaxel was loaded in the hydrophobic region between the TL and PC. Cisplatin was loaded through non-covalent interactions onto the outside of the two or three layer gold nanoparticles. The release of drug was assessed based on particle surface modifications and drug physiochemical properties. Mechanisms of drug release were further assessed by evaluation of kinetic models, including: zero-order kinetic model, first-order kinetic model, simplified Higuchi model, and Korsmeyer-Peppas model [27]. Finally, an assessment of nanoparticle efficacy was performed in 3D cell culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

HAuCl4 (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA), trisodium citrate (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1-Hexadecanethiol (TL) (Sigma Aldrich), 100% Ethanol (Decon Labs, King of Prussia, PA, USA), Chloroform (Sigma Aldrich), L-Phosphatidylcholine (PC) (Sigma Aldrich), High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) (Lee Biosolutions, St. Louis, MO, USA), Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), Cisplatin (Sigma Aldrich), Paclitaxel (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), Acetonitrile (Sigma Aldrich), Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Sigma Aldrich)

Synthesis of citrate gold nanoparticles

Particles were synthesized using a method in which gold chloroauric acid is reduced by trisodium citrate as previously described [28]. In this process, 2.2–2.4 mL 1% weight/volume (wt/v) citrate is added to 200 mL of boiling 0.01% wt/v HAuCl4, and the solution is allowed to continue boiling for 10 minutes to promote the reaction of sodium citrate to citric acid. Once the reaction is completed, the solution cools at room temperature before concentration using a rotovapor (Buchi Rotovapor System, BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) to ~20 mL at 20 OD. After the nanoparticles are concentrated, surface modifications are added as described below.

Particle functionalization with PC and HDL

The first layer applied to the citrate gold nanoparticles was 1-Hexadecanethiol dissolved in ethanol. Previous studies have shown that thiol compounds can displace surface-bound citrate from gold nanoparticles due to the strong binding affinity between gold and thiol in comparison to the electrostatic binding with citrate [29–31]; a comprehensive review concerning the covalent interaction between gold and sulfur was recently published [31]. This creates a hydrophobic nanoparticle, as the hydrocarbon chains of the thiol compound will point outward from the gold core. While stirring, 20 mL pure ethanol was placed in a beaker with 60 μL 1-Hexadecanethiol being added secondly to reach a molar ratio between thiol and gold nanoparticles of 2,500 : 1. The 1-Hexadecanethiol solution was added slowly to the nanoparticle solution over the next 10 minutes, while also undergoing sonication. The sample was further sonicated for two hours, and then placed for 12 hours on an orbital rocker (Boekel Scientific, Feasterville, PA, USA). The sample was spun down, and the pellet was washed twice with ethanol and sonicated before suspension in chloroform. The second functionalization was the addition of the PC to the surface of nanoparticles. The stock solution was made by diluting PC in chloroform (2mg/mL), and 100 μL (molar ratio 2000 PC: 1 NP) was added to the particles after the TL layer, and allowed to set overnight on an orbital rocker. The solutions were transferred to glass tubes and the chloroform evaporated at ambient temperature. This process completed the two layer gold nanoparticles containing gold core, TL, and PC. The three-layered nanoparticles were created by optimizing the ratio of HDL to particle optical density (1 mg HDL per 20 OD nanoparticle), and allowed to react overnight after two hours of sonication.

Addition of chemotherapeutics to nanoparticles

The amount of chemotherapeutic loaded was chosen to achieve a molar concentration upon release typical for cell culture experiments with these drugs. Paclitaxel was loaded after the sample completed 12 hours on the orbital rocker (see above). After nanoparticles were resuspended in 9 mL chloroform at 5 OD, an additional 1 mL of chloroform containing 5 mg paclitaxel was added to the solution. Nanoparticles were sonicated for two hours before the solution was placed on an orbital rocker for six hours. The solution was further modified to add the second layer of PC to the surface of the nanoparticles. While paclitaxel was loaded into the hydrophobic region created between the TL and PC layer, cisplatin was loaded at two different areas dependent upon the layering. For the two layer gold nanoparticles, cisplatin was added after the addition of PC. This was done by transferring the solutions to glass tubes and the chloroform evaporated at ambient temperature. Next, the nanoparticles were resuspended in 10 mL ultrapure H2O (Purelab Ultra, Elga Labwater, UK) containing 7.5 mg cisplatin to accomplish a molar ratio of 350 cisplatin molecules per nanoparticle. For the three layer gold nanoparticles, cisplatin was added after the addition of HDL by synthesizing the particles as described above; after HDL was added and allowed to react for two hours, the solution was removed, and 7.5 mg cisplatin was added. Excess drug was removed from the solution by centrifuging the particles at 7000 rpm for 25 minutes, removing the supernatant, and re-suspending the particles in the corresponding solvent. Washing was performed twice.

Nanoparticle Characterization

Nanoparticle identity was verified as follows: (1) Maximum absorption wavelengths were obtained using the Varian Cary 50 Bio Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectrometer (McKinley Scientific); (2) size and zeta potential measurements were obtained using the ZetaSizer Nanoseries ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK); (3) DLS (dynamic light scattering, also known as Photon Correlation Spectroscopy) was used to determine hydrodynamic size in solution based upon Brownian motion; (4) shape and size were determined using a Zeiss Supra 35VP (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) scanning electron microscope (SEM); (5) presence of lipids on the particle cores was confirmed using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) instrument (Perkin Elmer Spectrum BX; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and through visual analysis using the SEM.

Drug Release Studies

In vitro drug release studies were carried out using dialysis tubing cellulose membrane with an average flat width of 25 mm and 12,000 MW cutoff (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The prepared drug-loaded nanoparticles were added to dialysis tubes and subject to dialysis by submerging the tubing into a beaker containing 500 mL 1X PBS at pH 7.4. We chose to evaluate this release in saline solution [14,25,32,33] as the simplest system from which parameters could also possibly be extracted for mathematical modeling. The solution was sonicated continuously throughout the release evaluation using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature covered with Parafilm to minimize evaporation. At established time intervals, 3 mL samples of PBS containing drug were removed and replaced with fresh buffer to ensure a constant volume. The amount of drug in each sample was determined using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). Cumulative drug release versus time was expressed by the following equation (Eq. 1):

| Eq. (1) |

where [Drug]t refers to the concentration of drug release at time t and [Drug]total is the total amount of drug loaded onto the nanoparticles.

Drug Detection using HPLC

Samples of paclitaxel and cisplatin were analyzed using a Waters Alliance e2695 HPLC equipped with a Waters 2998 photodiode array UV/Vis detector and a μRPC C2/C18 ST 4.6/100 column (GE Healthcare, catalog number 17-5057-01). Initial injection conditions were 100% water/0.1% TFA immediately followed upon injection by 5 minutes with 100% water/0.1% TFA, 35 minutes of linear gradient to 100% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA, 5 minutes at 100% acetonitrile, followed by a return to 100% water/0.1% TFA to prepare the column for the next run. Total run time was 55 minutes. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. Spectrophotometric data were collected from 200 to 800 nm. The baseline for each run was monitored at 260 nm and 280 nm. A standard calibration curve was created for paclitaxel (0.01 μM to 10 μM plus a blank sample) and cisplatin (2.5 μM to 500 μM plus a blank sample) by injection of pure compounds dissolved in water or buffer. The peak corresponding to paclitaxel was integrated at 230 nm to minimize overlap of peaks belonging to interfering compounds and to maximize peak area. Cisplatin was integrated at 380 nm for the same reasons. After elution, peaks were integrated using Waters Empower software. A calibration curve was generated by plotting peak area vs. concentration using Microsoft Excel. Analytical samples of each compound were then compared to the standard curve to determine their approximate concentration.

Determination of drug incorporation efficiency

Drug incorporation efficiency (I.E.) (%) was expressed as the percentage of drug in the produced nanoparticles with respect to the initial amount of drug that was used for synthesizing the nanoparticles [32]. This calculation was determined using HPLC as described above in conjunction with the following equation (Eq. 2):

| Eq. (2) |

Mechanism of Drug Release

To assess the mechanism of drug release, in vitro release patterns were analyzed using four kinetic models: zero-order kinetic model, first-order kinetic model, simplified Higuchi model, and Korsmeyer-Peppas model. The zero order model is associated with drug dissolution that is independent of drug concentration (Eq. 3) [34]:

| Eq. (3) |

where Qt is the amount of drug dissolved in time t, Q0 is the initial amount of drug in solution, and k0 describes the zero-order rate constant. The first order model describes drug release that is concentration-dependent (Eq. 4) [34]:

| Eq. (4) |

where C refers to drug concentration and k is the first order rate constant. This equation can also be expressed as (Eq. 5):

| Eq. (5) |

where C0 corresponds to the initial concentration of drug. The simplified Higuchi model utilizes the following equation to describe drug release from matrix and polymeric systems (Eq. 6) [35]:

| Eq. (6) |

where (Mt/M·) is the cumulative amount of drug released at time t, and k is the Higuchi constant based upon the formulation of the system. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model describes drug release from matrix and polymeric systems through the following equation (Eq. 7) [36]:

| Eq. (7) |

where (Mt/M·) is the cumulative amount of drug released at time t, k′ is the kinetic constant, and n is the exponent that describes a particular diffusion mechanism.

The first 60% of drug release is typically sufficient for determining the best fit model of drug release [37]. For each model, a graph was constructed using Microsoft Excel from which the rate constant and correlation values were obtained by applying a linear regression fit. The zero-order kinetic model was obtained by plotting cumulative % drug release vs. time. The first-order kinetic model was analyzed by plotting log cumulative % of drug remaining vs. time. The Higuchi model was evaluated by plotting cumulative % drug release vs. square root of time, while the Korsmeyer-Peppas model was analyzed by plotting log cumulative % drug release vs. log time.

Evaluation of Nanoparticle Efficacy

Three human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, A-549, PC-9, NCI-H358, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, Corning Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cellgro, Corning Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Cellgro, Corning Inc.) in standard culture conditions. All cells were grown to 80% confluence before harvesting. Cells were seeded onto 24-well ultra-low cluster plates (Costar, Corning Inc.) at 1×105 cells per well, and shaken for ~10 minutes to promote aggregation. Cells were incubated for 5 days and then exposed to either free drug (cisplatin or paclitaxel) or nanoparticles (two- or three-layer) with one of these drugs. Drug concentrations ranged from 0 to 1024 (μM cisplatin or nM paclitaxel) in 4X increments (0, 0.0625, 0.25, 1, etc.) for 48 h. Spheroids were exposed to the same concentration of nanoparticle-loaded drug as free drug, with the dose calculated by considering the loading efficiency from the HPLC data showing the drug concentration in the nanoparticles and the percent drug released at 48 h. Negative controls (without drug and without nanoparticles) were seeded and incubated under the same conditions. At the end point spheroids were disaggregated using trypsin (0.05%), and cell viability was assessed via trypan blue exclusion counts.

Statistics

All drug release and cell viability measurements were performed in triplicate. Error bars denote standard deviation.

RESULTS

Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

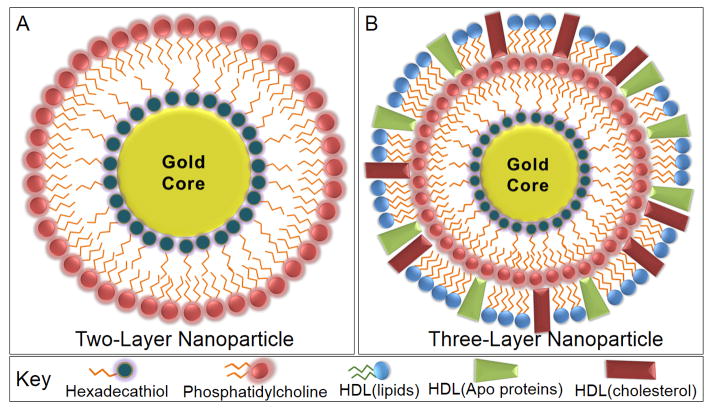

We have previously characterized the diffusivity and transport of two and three layer gold nanoparticles in 3D cell culture [26], finding that they performed better than PEG-coated versions. Here, we examine the in vitro release profiles of cisplatin and paclitaxel from such nanoparticle formulations. We evaluate nanoparticles functionalized with TL and PC for the development of an inner hydrophobic region with a surrounding hydrophilic exterior, or TL, PC and HDL as three layered gold nanoparticles (Figure 1). To ensure proper synthesis and surface functionalization, nanoparticles were characterized through UV-Vis (ultraviolet-visible) spectroscopy to determine maxima absorbance, SEM (scanning electron microscopy) for morphological and size analysis, DLS (dynamic light scattering) to determine hydrodynamic size in solution based upon Brownian motion, zeta potential to determine surface charge, and FTIR (Fourier transform infrared) analysis to ensure the presence of surface modifications.

Figure 1.

Nanoparticles were synthesized with either two or three layers, in which a lipid containing a hexadecanethiol (TL) head group was applied to the gold surface. This displaced the citrate stabilizer, forming a hydrophobic nanoparticle. The addition of phosphatidylcholine (PC) to the solution promoted water solubility as the hydrophobic tails of PC bound the tails of TL. The two layer gold nanoparticles (A) were compared to three layer nanoparticles (B), in which HDL was further added to alter the in vivo reactivity, drug release profile, and enhancement of tumor targeting.

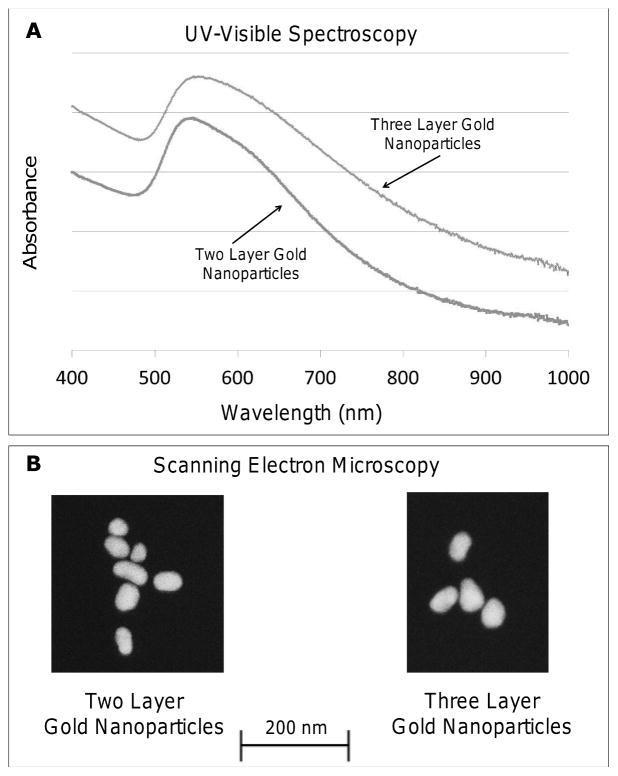

Optical measurements were performed through UV-Vis spectroscopy and offer information regarding nanoparticle size, shape, and agglomeration status. The spectra of two layer gold nanoparticles exhibited a maximum absorbance peak at 540 nm, while three layer gold nanoparticles displayed a similar spectrum with a maximum absorbance of 541 nm (Figure 2A). This particular wavelength near 534–545 nm is characteristic for polydispersed gold nanoparticles with a diameter 50–70 nm [38]. We note that preliminary observations examining stability in fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 hours showed the nanoparticles to be relatively stable in FBS (data not shown), with both two and three layer nanoparticles showing minute shifts from the maximum absorbance values reported here. Visual determination of nanoparticle size was accomplished using SEM, showing that two layer gold nanoparticles had an average size of 47.1 ± 12.6 nm, while three layer gold nanoparticles were 33% larger with an average size of 62.8 ± 14.9 nm (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Gold nanoparticles were characterized using UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine the maximum absorbance wavelength and with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for size analysis. (A) The maximum absorbance of two and three layer gold nanoparticles was 540 nm and 541 nm, respectively. (B) SEM showed the size of two layer gold nanoparticles at 47.1 ± 12.6 nm and three layer gold nanoparticles at 62.8 ± 14.9 nm.

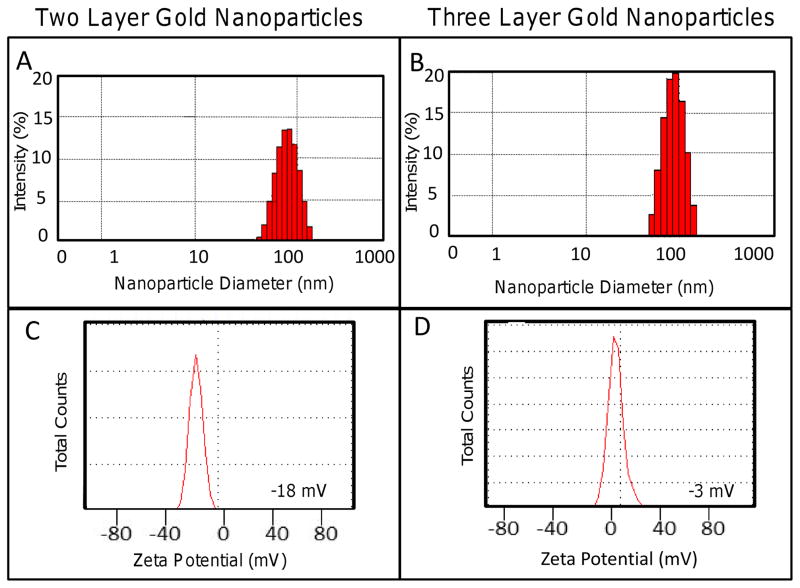

DLS establishes the hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles in solution by considering Brownian motion. Figure 3 reveals the hydrodynamic size for two and three layer gold nanoparticles at 74.91 ± 13.3 nm and 85.26 ± 18.7 nm, respectively (Table 1). The surface charge of two and three layer gold nanoparticles, determined through zeta potential analysis as illustrated in Figure 3, shows that HDL-coated nanoparticles (−2 mV) were more neutrally charged in comparison to anionic PC-coated gold nanoparticles at −20 mV (Table 1). For comparison, un-coated gold nanoparticles possessed a zeta potential near −40 mV, while thiol coated nanoparticles had approximately −30 mV.

Figure 3.

Gold nanoparticles were characterized using dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine hydrodynamic size in solution and with zeta potential to determine surface charge. (A) The hydrodynamic size of two and three layer gold nanoparticles was determined to be 74.91 ± 13.3 nm and 85.26 ± 18.7 nm, respectively. (B) Two layer gold nanoparticles exhibited an anionic charge of −20 mV, while three layer gold nanoparticles were more neutrally charged at −2 mV.

Table 1.

Characterization Results of Two and Three Layer Gold Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle | Surface Modification | Max Absorbance (nm) | SEM Size (nm) | DLS Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC | 540 | 47.1 (12.6) | 74.91 (13.3) | −20 |

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC-HDL | 541 | 62.8 (14.9) | 85.26 (18.7) | −2 |

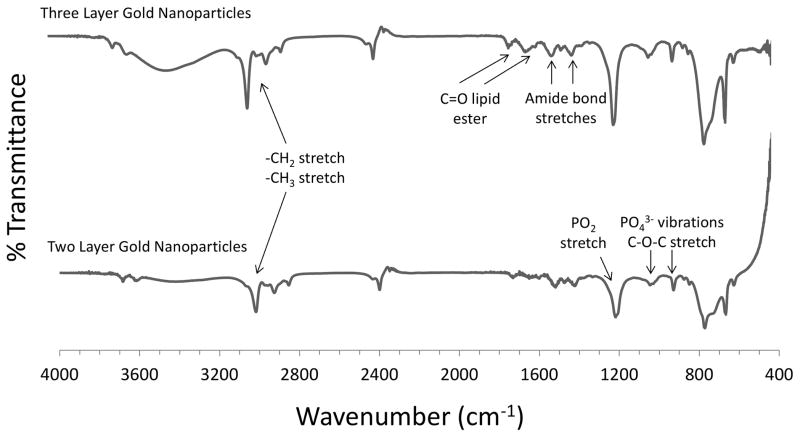

FTIR was employed to confirm the presence of surface modifications (Figure 4). Spectra obtained from two and three layer gold nanoparticles were compared with spectra of pure PC [39] and HDL [40]. Two layer gold nanoparticles functionalized with TL and PC exhibited several signature peaks that confirmed the presence of TL and PC onto the gold core. Signature peaks included PO43− group vibrations between ~850–1000 cm−1, a C–O–C stretch ~1100 cm−1, a [(-CH2)n] rocking vibration ~720 cm−1, both asymmetric and symmetric –CH2 (2880 cm−1) and –CH3 (2950 cm−1) stretch and vibration, and a -CH2 stretching and scissoring at 1375 and 1470 cm−1, respectively. Slight differences in the spectra can be attributed to other chemicals used in the synthesis of the layered nanoparticles, including TL and colloidal gold. For HDL-coated nanoparticles, the asymmetric and symmetric –CH2 (2880 cm−1) and –CH3 (2950 cm−1) stretch and vibration occur along with C=O from the lipid ester ~1700–1800 cm−1, along with amide bond stretches between 1500–1700 cm−1, and a phospholipid P=O2 stretch ~1250 cm−1. As these nanoparticles were also coated with TL and PC, distinct bands from both TL and PC were expected to be present in the spectra of the three layer formulation.

Figure 4.

Gold nanoparticle surface modifications were confirmed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). The peaks were matched with those of pure phosphatidylcholine (PC) and HDL. The PC-coated two layer gold nanoparticles exhibited multiple peaks that were used for conformation, including a [(-CH2)n] rocking vibration ~720 cm−1, a PO43− group vibration between 820–1000 cm−1, C-O-C stretch ~1100 cm−1, - CH2 stretching and scissoring (1375 and 1470 cm−1). The HDL-coated three layer gold nanoparticles exhibited several peaks including: asymmetric and symmetric –CH2 (2880 cm−1), –CH3 (2950 cm−1) stretch and vibration, C=O from the lipid ester between 1700–1800 cm−1, amide bond stretches between 1500–1700 cm−1 and a phospholipid P=O2 stretch ~1250 cm−1.

Drug Release from Two and Three Layered Gold Nanoparticles

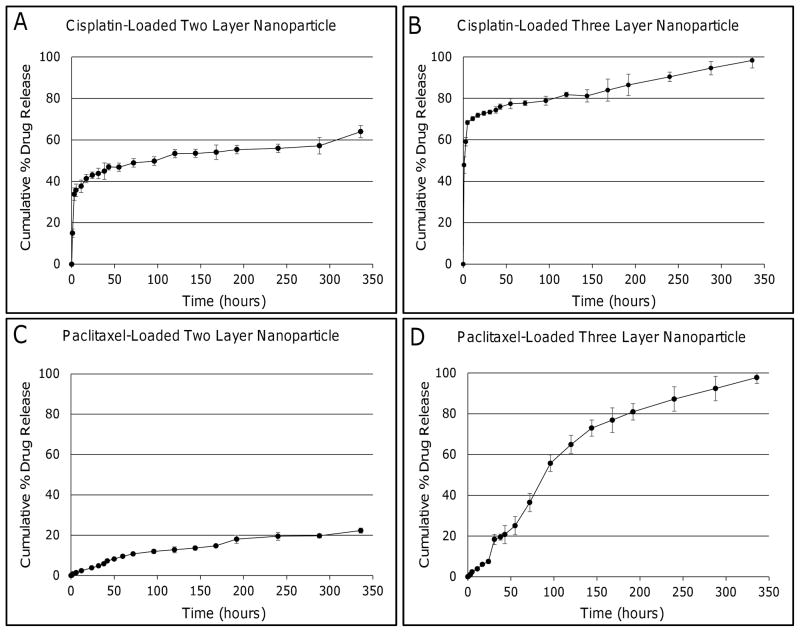

Both two and three layer gold nanoparticles were loaded with either cisplatin or paclitaxel to evaluate the effect that the surface modifications may have on hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release kinetics. The cumulative percent of drug release was plotted against time to analyze the kinetics for each case (Figure 5). For cisplatin-loaded two layer gold nanoparticles, an initial burst of 35.7 ± 2.3% was observed during the first 5 hours, followed by a steady release for the next 14 days (336 hours), with 64.0 ± 2.4% of loaded cisplatin released (Figure 5A). Three layer gold nanoparticles loaded with cisplatin also showed an initial burst of 68.4 ± 1.0%, followed by a steady profile with 98.3 ± 2.6% of loaded drug released at the end of 14 days (Figure 5B). Drug release within the first 24 hours was plotted separately to highlight the initial burst followed by the switch to a more linear profile (Figure A1).

Figure 5.

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release profiles from gold nanoparticles coated with PC and TL (two layer), or PC, TL, and HDL (three layer). (A) Cisplatin-loaded two layer gold nanoparticles exhibited a burst during the first 5 hours, with ~35% of drug being released. A steady release followed over the next 14 days. (B) Cisplatin-loaded three layer gold nanoparticles also experienced an initial burst with ~70% of encapsulated drug being released within the first 5 hours. Drug release then became steady for the next 14 days. (C) Paclitaxel release from two layer gold nanoparticles was steady with only ~20% of encapsulated paclitaxel released during the 14 days. (D) Almost 100% of paclitaxel encapsulated within three layer gold nanoparticles was released by 14. Error bars represent standard deviation (n=3).

Paclitaxel release from two layer gold nanoparticles showed a linear profile with only 22.3 ± 1.5% of loaded drug being released at the end of 14 days, indicating that nearly 78% of entrapped drug was still attached to the nanoparticles (Figure 5C). In contrast, the three layer formulation effectively released 97.8 ± 2.3% of encapsulated drug by day 14 (Figure 5D). The first 24 hours were also plotted separately to highlight the initial release (Figure A1).

The amount of drug loaded onto the nanoparticles was determined indirectly by measuring the amount of drug that did not load (Table 2). For two layer gold nanoparticles, 68.4 ± 7.1% of cisplatin and 99.1 ± 0.7% of paclitaxel were effectively loaded. For the three layer formulation, higher drug incorporation efficiencies were obtained with of 78.9 ± 4.9% cisplatin and 99.4 ± 0.4% of paclitaxel loaded. Nearly 100% of paclitaxel became encapsulated, suggesting that even higher drug concentrations may be possible.

Table 2.

Drug Incorporation Efficiency of Two and Three Layer Gold Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle | Surface Modification | Incorporated Drug | Drug Incorporation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC | Cisplatin | 68.4 ± 7.1 |

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC-HDL | Cisplatin | 78.9 ± 4.9 |

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC | Paclitaxel | 99.1 ± 0.7 |

| Citrate Gold | TL-PC-HDL | Paclitaxel | 99.4 ± 0.4 |

Kinetic models of drug release

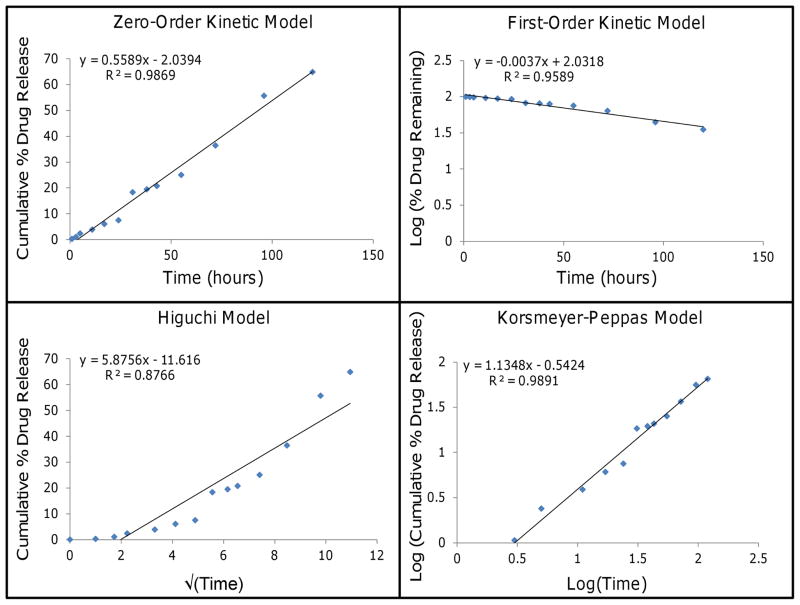

Mathematical models may be useful to evaluate the kinetics and mechanism of drug release from nanoparticles. The release curves from Figure 5 were fitted to four distinct models to determine which one exhibited the highest correlation with experimental results (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rate Constants and Correlation Coefficients Obtained from Modeling Drug Release from Two and Three Layer Gold Nanoparticles through the following: zero-order kinetic model, first-order kinetic model, simplified Higuchi model, and Korsmeyer-Peppas model.

| Surface Modification | Incorporated Drug | Zero-Order | First-Order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer-Peppas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | r2 | k | r2 | k | r2 | n | r2 | ||

| TL-PC | Cisplatin | 0.0725 | 0.8445 | 0.0008 | 0.5875 | 1.8554 | 0.8061 | 0.1248 | 0.9811 |

| TL-PC-HDL | Cisplatin | 11.699 | 0.7284 | 0.0890 | 0.8478 | 30.162 | 0.9287 | 0.2716 | 0.9897 |

| TL-PC | Paclitaxel | 0.0668 | 0.9127 | 0.0003 | 0.9313 | 1.294 | 0.9862 | 0.6787 | 0.9846 |

| TL-PC-HDL | Paclitaxel | 0.5589 | 0.9869 | 0.0037 | 0.9589 | 5.8756 | 0.8766 | 1.1348 | 0.9891 |

Hydrophobic drug (paclitaxel) release from three layer gold nanoparticles exhibited high correlation with the zero-order kinetic model and the Korsmeyer-Peppas models, both with R2>0.98 (Figure 6). The other cases of drug release are shown in the Supplement (Figure A2–4). Release of paclitaxel from the two layer gold nanoparticles also showed high correlation with the simplified Higuchi model (R2=0.9862), possibly due to the profile curve denoting an early stage of release since only 22.3 ± 1.5% of paclitaxel was unloaded by day 14. Both two and three layer gold nanoparticles loaded with hydrophilic drug (cisplatin) correlated best with the Korsmeyer-Peppas model with R2>0.98, suggesting that aggregate drug release from multi-layered gold nanoparticles may be modeled similar to a polymeric system undergoing degradation [41].

Figure 6.

Paclitaxel release from three layer gold nanoparticles (points, representing average values) fitted to kinetic models (lines). The first 60% of cumulative release was fitted to each kinetic model: zero-order kinetic model by plotting cumulative % drug release vs. time, first-order kinetic model by plotting log of % drug remaining vs. time, simplified Higuchi model by plotting cumulative % drug release vs. square root of time, and Korsmeyer-Peppas model by plotting log cumulative % drug release vs. log time. Both the zero-order kinetic and the Korsmeyer-Peppas models showed high correlation with R2>0.98.

Assessment of Efficacy

The cytotoxicity of drug-loaded two- and three-layer gold nanoparticles was evaluated in 3D cell culture by comparing the inhibitory drug concentration to achieve a 50% decrease in cell viability (the “IC50”). Although 3D cell culture is a gross simplification of the in vivo condition, it allows for the establishment of tissue structures in which the effects of diffusion and transport are not negligible (unlike monolayer cell culture), thus mimicking poorly vascularized regions of solid tumors or avascular tumor nodules. Such a culture system allows for the possibility of tissue penetration by the two- and three-layer nanoparticle systems, as evaluated previously [26], with the goal to overcome the diffusion barrier presented by the typically irregular tumor vasculature during systemic delivery. Table 4 shows that for three different non-small cell lung cancer cell lines, the nanoparticles achieved a lower IC50 than with free drug, indicating that they were at least as efficacious as the traditional chemotherapeutics.

Table 4.

Assessment of efficacy of drug-loaded Two and Three Layer Gold Nanoparticles in 3D cell culture with three non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines.

| A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Incorporated Drug | Cell Line | Type | IC50 (μM) |

| Cisplatin | A549 | Free Drug | 26.6 ± 3.0 |

| Two Layer | 14.8 ± 0.4 | ||

| Three Layer | 15.9 ± 1.2 | ||

| H358 | Free Drug | 32.9 ± 3.4 | |

| Two Layer | 17.4 ± 0.4 | ||

| Three Layer | 10.8 ± 1.3 | ||

| PC9 | Free Drug | 16.6 ± 4.5 | |

| Two Layer | 13.4 ± 1.4 | ||

| Three Layer | 7.6 ± 2.4 | ||

| B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Incorporated Drug | Cell Line | Type | IC50 (nM) |

| Paclitaxel | A549 | Free Drug | 38.3 ± 4.2 |

| Two Layer | 28.5 ± 6.9 | ||

| Three Layer | 34.2 ± 2.6 | ||

| H358 | Free Drug | 45.6 ± 8.1 | |

| Two Layer | 19.0 ± 1.0 | ||

| Three Layer | 25.2 ± 3.3 | ||

| PC9 | Free Drug | 30.7 ± 4.6 | |

| Two Layer | 20.0 ± 1.6 | ||

| Three Layer | 24.4 ± 2.0 | ||

DISCUSSION

We synthesized two and three layer gold nanoparticles to analyze the effect of surface modifications on the loading and release kinetics of two commonly utilized chemotherapeutics, cisplatin and paclitaxel, representing hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, respectively. Two layer gold nanoparticles were synthesized through the addition of a TL layer and PC coating [26], thus creating a hydrophobic region accessible to water insoluble drugs such as paclitaxel (Figure 1). Besides aiding in drug entrapment, a PC coating was previously shown to significantly reduce nanoparticle cytotoxicity [42]. PC-coated gold nanoparticles were synthesized by first displacing the citrate stabilizer with TL. The strong binding affinity felt by the head group of TL for the gold core creates water insoluble nanoparticles, as the hydrophobic tails of TL point outward from the gold cores (Figure 1). Addition of PC to the outer layer of TL re-establishes water solubility, as the tail of the PC molecule binds tail-to-tail with TL. This process is expected to effectively create a hydrophobic region between the TL and PC layers that can be utilized for loading hydrophobic drugs. The two layer nanoparticles may be considered analogous to liposomes, yet containing an inner gold core. Addition of the bilayer to the outside of gold nanoparticles is expected to increase the bioavailability and decrease immunogenicity, as PC is a primary component of cellular membranes.

Three layer gold nanoparticles were synthesized through the addition of HDL to the surface of PC-coated two layer gold nanoparticles. This modification is expected to enhance tumor-targeting capabilities, especially for hepatocellular carcinoma as HDL receptors are unregulated in liver cancer [43]. Cisplatin was loaded after the addition of PC for the two layer gold nanoparticles or after the addition of HDL for the three layer gold nanoparticles, and expected to exhibit faster release kinetics in comparison to paclitaxel due to the weakness of the non-covalent linkages (Figure 1).

Nanoparticles were characterized to confirm proper synthesis and modifications. Currently, a set of characterization standards for characterizing nanoparticles does not exist [44], thus, this study utilized common instrumentation to ensure size, surface charge, and surface functionalization. While SEM (Figure 2) and DLS (Figure 3) are two common techniques for determining nanoparticle size [45], measurement variances are often seen between samples using both instruments [46,47]. As the head groups of PC are negatively charged, it was expected that two layer nanoparticles would be moderately anionic. A previous study showed that the zeta potential of PC-coated nanoparticles varies based upon pH, from 14 mV at pH=5 to −40 at pH=7 [48]. Due to the orientation of the PC onto the nanoparticles on top of the thiol compound, a slightly negative zeta potential was obtained. The zeta potential of HDL coated nanoparticles was expected to be more neutrally charged as HDL is a neutrally charged molecule [49], as confirmed in Table 1. Previous studies have shown that highly cationic or anionic nanoparticles experience increased uptake in the liver, thus inactivating the nanoparticles before they have time to reach the target destination and resulting in possible liver toxicity [50–52]. It has been shown that nanoparticles with a slightly negative charge may have low liver uptake and enhanced accumulation in solid tumors [50], thus suggesting that such nanoparticles will display improved biocompatibility, reduced RES sequestering, and enhanced drug delivery to solid tumors.

FTIR confirmed the presence of surface modifications by comparing the peaks of two and three layer gold nanoparticles to pure PC and HDL (Figure 4). Two layer gold nanoparticles coated with TL and PC were expected to have a large peak associated with –CH2 and –CH3 groups (~3000 cm−1) along with phosphate group vibrations ~900 cm−1 [33,53]. While these bands were present in the nanoparticle spectra, the intensity of the peaks was diminished from the spectra of pure PC. This can be attributed to the layering process, as the PC is loaded on top of TL, and both are attached to gold cores. For HDL-coated nanoparticles, bands were expected to show with lipid esters between 1700–1800 cm−1 and two amide stretches between 1500–1700 cm−1 [54]. As the HDL is loaded on top of the PC-coated nanoparticles, PC representative peaks were expected to be visible in the spectra of the three layer gold nanoparticles.

Cisplatin release from two and three layer gold nanoparticles showed an initial burst during the first five hours followed by a steady release for the following 14 days (Figure 5 A–B). An initial burst is common for nanoparticles, yet is highly dependent upon surface polymers and strength of drug attachment [55]. As cisplatin was bound to the nanoparticles non-covalently, the initial burst was expected. In comparison, paclitaxel showed a steady drug release profile (Figure 5 C–D). Minimal paclitaxel was released within 14 days from the two-layer formulation, which can be attributed to its tight encapsulation within the hydrophobic layer created by the TL and PC. While PC may be degraded inside the body, it will stay relatively intact in PBS, thus not allowing most of the drug to escape. However, the addition of HDL to the surface of PC disrupts the layer allowing for paclitaxel to slowly release from the hydrophobic region. This hypothesis is supported by the work of Scherphof et al. who determined that HDL could disrupt the structural integrity of liposomes synthesized with PC [56]. This effect could explain the difference between the two and three layer gold nanoparticles loaded with paclitaxel, showing a 5-fold increase in release from the three layer formulation coated with HDL in comparison to the two layer (Figure 5 C–D). This also suggests that the addition of HDL may not be creating an actual layer on the outside of the nanoparticles, but rather insert HDL into the PC layer.

Paclitaxel release was best fitted by the simplified Higuchi model for the two layer nanoparticles and the Korsmeyer-Peppas model and zero-order kinetic model for the three layer nanoparticles, both with correlation values >0.98. For these nanoparticles, the long term sustained release could make them suitable candidates for therapeutic applications. Cisplatin release from two and three layer gold nanoparticles was best modeled by the Korsmeyer-Peppas equation. Both the simplified Higuchi model and Korsmeyer-Peppas models describe drug release from degrading matrix and polymeric systems, thus suggesting that the aggregate drug released from multi-layered gold particles confined within a dialysis bag may be modeled similar to a system which undergoes degradation. The Higuchi model is based upon the following assumptions: (1) diffusion of drug only occurs in a single dimension, (2) negligible matrix swelling and dissolution, (3) much smaller drug molecules than system thickness, (4) constant drug diffusivity, (5) release environment acts as a perfect sink, and (6) much higher drug solubility than matrix initial drug concentration [34]. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model is a semi-empirical relation also known as the Power law, in which the fraction of drug release is exponentially related to the time for release. Two main assumptions include the following: (1) the equation is only applicable for the first 60% of drug release and (2) the release must occur in a single dimension [34, 57]. The single dimension is constructed by the release of drug radially outward from the source, thus making it possible to model a 1-D problem.

For comparison, we also evaluated the Weibull model as a possible candidate for describing the drug release. While this model is a general empirical equation that is widely applied to drug release from pharmaceutical dosage forms, the model is limited by the inability to establish in vivo and in vitro correlation and the lack of parameters that can be related to the drug dissolution rate [57]. The Weibull model exhibited low correlation for cisplatin-loaded two and three layer gold nanoparticles, with R2 values of 0.7617 and 0.8792, respectively. The model was a somewhat better fit for the paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles, with the two layer gold nanoparticles having R2=0.9313 and the three layer formulation R2=0.9743.

In contrast to polymeric or matrix nano-materials in which drugs are loaded within the nanocarrier structure, gold surfaces allow for drug molecule attachment via charge interactions and thiol-gold linkages that approach covalent bonds in strength. Based on desired release profiles and sequestration of molecules due to particular physical properties (such as charge and hydrophobicity), there may be applications for which a layered system is easier to design using gold instead of polymeric nano-materials. Thus, citrate gold particles represent an initial step to build a multilayer system on a gold surface, which can be used to elucidate interactions with cells. The next step would be to transition to a gold coated particle capable of absorbing light at a specified wavelength to generate heat and to use this energy to release drugs from the nanoparticle, thus leading to enhanced localized delivery. However, to enhance release requires particles which absorb light in a region transparent to tissue, such as near-infrared absorbing gold nanoparticles (nanorods, gold silica nanoshells or gold-sulfide aggregate nanoparticles). Colloidal gold particles are unsuitable for thermal absorption as the wavelength of light used to activate these particles (~540 nm) will harm living tissues due to absorption of energy at this wavelength [58].

Enhanced understanding of hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release kinetics from multi-layered gold nanoparticles could result in the development of combinatorial treatment strategies targeting tumor cells. Future work will assess the efficacy of cisplatin and paclitaxel from TL, PC, and HDL coated versions of gold nanoparticles in vivo; a preliminary assessment of in vitro efficacy shows promise in this regard. Here, we have chosen to focus on the drug release kinetics as a first step in this evaluation. The results may further help to calibrate computational simulations that can provide insight into the complex dynamics of nanoparticle transport and drug release within solid tumors [59–62].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release was assessed from layered Au nanoparticles

Layers were –thiol/phosphatidylcholine, or both plus high density lipoprotein

Layers help to modulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug release kinetics

High density lipoprotein enhances long term release of hydrophobic drug

Korsmeyer-Peppas kinetic model best described each drug release scenario

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. André M. Gobin for useful advice and discussions.

FUNDING SOURCES

National Institutes of Health Grant Number 1P30GM106396 from the National Center for Research Resources, and the Department of Bioengineering and James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DLS

Dynamic Light Scattering

- FTIR

Fourier Transform Infrared

- HDL

High Density Lipoprotein

- HPLC

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PC

L-α-Phosphatidylcholine

- PEG

poly (ethylene glycol)

- RES

Reticulo-endothelial System

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscope

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

- TL

1-Hexadecanethiol

- UV-Vis

Ultraviolet-Visible

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplemental Information Available. Graphs highlighting drug release from two- and three-layer gold nanoparticles during the first 24 hours are included. Additional graphs illustrating model fitting to release curves are also shown.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clegg A, Scott DA, Hewitson P, Sidhu M, Waugh N. Clinical and cost effectiveness of paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Thorax. 2002;57(1):20–28. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberoi HS, Nukolova NV, Kabanov AV, Bronich TK. Nanocarriers for delivery of platinum anticancer drugs. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2013;65(13–14):1667–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohndorf U-M, Rould MA, He Q, Pabo CO, Lippard SJ. Basis for recognition of cisplatin-modified DNA by high-mobility-group proteins. Nature. 1999;399(6737):708–712. doi: 10.1038/21460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz SB. Taxol (paclitaxel): mechanisms of action. Ann Oncol. 1994;5 (Suppl 6):S3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowinsky EK, Eisenhauer EA, Chaudhry V, Arbuck SG, Donehower RC. Clinical toxicities encountered with paclitaxel (Taxol) Seminars in Oncology. 1993;20(4 Suppl 3):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma P, Mumper RJ. Paclitaxel Nano-Delivery Systems: A Comprehensive Review. J Nanomedicine and Nanotechnology. 2013;4(2):1000164. doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.1000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(13):1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain S, Hirst DG, O’Sullivan JM. Gold nanoparticles as novel agents for cancer therapy. Brit J Radiol. 2012;85(1010):101–113. doi: 10.1259/bjr/59448833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Gu Y, Hu Y, Qian Z. Characterization of pH- and Temperature-sensitive Hydrogel Nanoparticles for Controlled Drug Release. J Pharm Sci Tech. 2007;61(4):303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jokerst JV, Lobovkina T, Zare RN, Gambhir SS. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2011;6(4):715–728. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols JW, Bae YH. Odyssey of a cancer nanoparticle: from injection site to site of action. Nano today. 2012;7(6):606–618. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longmire M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine-Uk. 2008;3(5):703–717. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heo DN, Yang DH, Moon HJ, Lee JB, Bae MS, Lee SC, et al. Gold nanoparticles surface-functionalized with paclitaxel drug and biotin receptor as theranostic agents for cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2012;33(3):856–866. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwu JR, Lin YS, Josephrajan T, Hsu MH, Cheng FY, Yeh CS, et al. Targeted Paclitaxel by Conjugation to Iron Oxide and Gold Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009 Jan 14;131(1):66–68. doi: 10.1021/ja804947u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding Y, Zhou Y-Y, Chen H, Geng D-D, Wu D-Y, Hong J, et al. The performance of thiol-terminated PEG-paclitaxel-conjugated gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(38):10217–10227. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren L, Huang XL, Zhang B, Sun LP, Zhang QQ, Tan MC, et al. Cisplatin-loaded Au-Au2S nanoparticles for potential cancer therapy: cytotoxicity, in vitro carcinogenicity, and cellular uptake. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85(3):787–796. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez-Paradinas S, Perez-Andres M, Almendral-Parra MJ, Rodriguez-Fernandez E, Millan A, Palacio F, et al. Enhanced cytotoxic activity of bile acid cisplatin derivatives by conjugation with gold nanoparticles. J Inorganic Biochem. 2014;131:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Goodisman J, Dabrowiak JC. Cyclodextrin capped gold nanoparticles as a delivery vehicle for a prodrug of cisplatin. Inorganic Chem. 2013;52(16):9418–9426. doi: 10.1021/ic400989v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai DH, Cho TJ, Elzey SR, Gigault JC, Hackley VA. Quantitative analysis of dendron-conjugated cisplatin-complexed gold nanoparticles using scanning particle mobility mass spectrometry. Nanoscale. 2013;5(12):5390–5395. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00543g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comenge J, Sotelo C, Romero F, Gallego O, Barnadas A, Parada TG, et al. Detoxifying antitumoral drugs via nanoconjugation: the case of gold nanoparticles and cisplatin. PloS One. 2012;7(10):e47562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomuleasa C, Soritau O, Orza A, Dudea M, Petrushev B, Mosteanu O, et al. Gold nanoparticles conjugated with cisplatin/doxorubicin/capecitabine lower the chemoresistance of hepatocellular carcinoma-derived cancer cells. J Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2012;21(2):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig GE, Brown SD, Lamprou DA, Graham D, Wheate NJ. Cisplatin-tethered gold nanoparticles that exhibit enhanced reproducibility, drug loading, and stability: a step closer to pharmaceutical approval? Inorganic Chem. 2012;51(6):3490–3497. doi: 10.1021/ic202197g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comenge J, Romero FM, Sotelo C, Dominguez F, Puntes V. Exploring the binding of Pt drugs to gold nanoparticles for controlled passive release of cisplatin. J Controlled Release. 2010;148(1):e31–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panczyk T, Jagusiak A, Pastorin G, Ang WH, Narkiewicz-Michalek J. Molecular Dynamics Study of Cisplatin Release from Carbon Nanotubes Capped by Magnetic Nanoparticles. J Phys Chem. 2013;117(33):17327–17336. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Likhitkar S, Bajpai AK. Magnetically controlled release of cisplatin from superparamagnetic starch nanoparticles. Carbohyd Polym. 2012;87(1):300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.England CG, Priest T, Zhang G, Sun X, Patel DN, McNally LR, et al. Enhanced penetration into 3D cell culture using two and three layered gold nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:3603–3617. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S51668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barzegar-Jalali M, Adibkia K, Valizadeh H, Shadbad MR, Nokhodchi A, Omidi Y, et al. Kinetic analysis of drug release from nanoparticles. J Pharmacy and Pharm Sciences. 2008;11(1):167–177. doi: 10.18433/j3d59t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frens G. Controlled Nucleation for the Regulation of the Particle Size in Monodisperse Gold Solutions. Nature Physical Sciences. 1973;241:20–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huo S, Ma H, Huang K, Liu J, Wei T, Jin S, He S, Liang XJ. Superior penetration and retention behavior of 50 nm gold nanoparticles in tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):319–330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bain CD, Biebuych HA, Whitesides GM. Comparison of Self-Assembled Monolayers on Gold: Coadsorption of Thiols and Disulfides. Langmuir. 1989;5:723–727. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Häkkinen H. The gold-sulfur interface at the nanoscale. Nat Chem. 2012;4(6):443–455. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca C, Simoes S, Gaspar R. Paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles: preparation, physicochemical characterization and in vitro anti-tumoral activity. J Controlled Release. 2002;83(2):273–286. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semalty A, Semalty M, Singh D, Rawat MSM. Preparation and characterization of phospholipid complexes of naringenin for effective drug delivery. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem. 2010;67(3–4):253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dash S, Murthy PN, Nath L, Chowdhury P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 2010;67(3):217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higuchi T. Mechanism of sustained-action medication. Theoretical analysis of rate of release of solid drugs dispersed in solid matrices. J Pharm Sci. 1963;52:1145–1149. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600521210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korsmeyer RW, Gurny R, Doelker E, Buri P, Peppas NA. Mechanisms of solute release from porous hydrophilic polymers. Int J Pharmaceutics. 1983;15(1):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bettini R, Catellani PL, Santi P, Massimo G, Peppas NA, Colombo P. Translocation of drug particles in HPMC matrix gel layer: effect of drug solubility and influence on release rate. J Controlled Release. 2001;70(3):383–391. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimling J, Maier M, Okenve B, Kotaidis V, Ballot H, Plech A. Turkevich method for gold nanoparticle synthesis revisited. J Phys Chem. 2006;110(32):15700–15707. doi: 10.1021/jp061667w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suleymanoglu E. The use of infrared spectroscopy for following drug-membrane interactions: probing paclitaxel (Taxol)-cell phospholipid surface recognition. Electronic J Biomedicine. 2009;3:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krilov D, Balarin M, Kosovic M, Gamulin O, Brnjas-Kraljevic J. FT-IR spectroscopy of lipoproteins--a comparative study. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2009;73(4):701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siepmann J, Peppas NA. Modeling of drug release from delivery systems based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2012;64(Supplement 0):163–174. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi H, Niidome Y, Niidome T, Kaneko K, Kawasaki H, Yamada S. Modification of gold nanorods using phosphatidylcholine to reduce cytotoxicity. Langmuir. 2006;22(1):2–5. doi: 10.1021/la0520029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang JT, Nilsson-Ehle P, Xu N. Influence of liver cancer on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Lipids Health Dis. 2006;5 doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall JB, Dobrovolskaia MA, Patri AK, McNeil SE. Characterization of nanoparticles for therapeutics. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2007;2(6):789–803. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benkovicova M, Vegso K, Siffalovic P, Jergel M, Luby S, Majkova E. Preparation of gold nanoparticles for plasmonic applications. Thin Solid Films. 2013;543(0):138–41. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bootz A, Vogel V, Schubert D, Kreuter J. Comparison of scanning electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation for the sizing of poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm And Biopharm. 2004;57(2):369–375. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(03)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wutikhun T, Ketchart O, Treetong T, Jaidee B, Warin C, Supaka S. Measurement and Compare Particle Size Determined by DLS, AFM and SEM. J Microscopy Society of Thailand. 2012;5(1–2):38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gándola K, Pérez SE, Irene PE, Sotelo AI, Miquet JG, Corradi GR, Carlucci AM, Gonzalez L. Mitogenic Effects of Phosphatidylcholine Nanoparticles on MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:1. doi: 10.1155/2014/687037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blume G, Cevc G. Molecular Mechanism of the Lipid Vesicle Longevity Invivo. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1993;1146(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90351-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao K, Li Y, Luo J, Lee JS, Xiao W, Gonik AM, et al. The effect of surface charge on in vivo biodistribution of PEG-oligocholic acid based micellar nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32(13):3435–3446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frohlich E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:5577–5591. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S36111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yah CS. The toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles in relation to their physiochemical properties. Biomed Res-India. 2013;24(3):400–413. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang F, Yang ZL, Zhang L, Weng SF, Wu JG. FT-IR study of the interaction between phosphatidylcholine and bovine serum albumin. Acta Phys-Chim Sin. 2004;20(10):1186–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krilov D, Balarin M, Kosovic M, Gamulin O, Brnjas-Kraljevic J. FT-IR spectroscopy of lipoproteins-A comparative study. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2009;73(4):701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Lim S, Ooi CP. Fabrication of Cisplatin-Loaded Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) Composite Microspheres for Osteosarcoma Treatment. Pharm Res. 2012;29(3):756–769. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scherphof G, Roerdink F, Waite M, Parks J. Disintegration of Phosphatidylcholine Liposomes in Plasma as a Result of Interaction with High-Density Lipoproteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1978;542(2):296–307. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costa P, Sousa Lobo JM. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;13(2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.El-Sayed I, Huang X, El-Sayed M. Selective laser photo-thermal therapy of epithelial carcinoma using anti-EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles. Cancer Letters. 2006;239(1):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frieboes HB, Wu M, Lowengrub J, Decuzzi P, Cristini V. A computational model for predicting nanoparticle accumulation in tumor vasculature. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e56876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frieboes H, Sinek J, Nalcioglu O, Fruehauf J, Cristini V. Nanotechnology in Cancer Drug Therapy: A Biocomputational Approach. In: Ferrari M, Lee A, Lee LJ, editors. BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology. Springer; US: 2006. pp. 435–460. [Google Scholar]

- 61.van de Ven AL, Wu M, Lowengrub J, McDougall SR, Chaplain MA, Cristini V, et al. Integrated intravital microscopy and mathematical modeling to optimize nanotherapeutics delivery to tumors. AIP Adv. 2012;2(1):11208. doi: 10.1063/1.3699060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu M, Frieboes HB, Chaplain MA, McDougall SR, Cristini V, Lowengrub J. The effect of interstitial pressure on therapeutic agent transport: Coupling with the tumor blood and lymphatic vascular systems. J Theor Biol. 2014;355:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.