Abstract

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) is an outcrossing hexaploid species with a large number of chromosomes (2n = 6x = 90). Although sweetpotato is one of the world’s most important crops, genetic analysis of the species has been hindered by its genetic complexity combined with the lack of a whole genome sequence. In the present study, we constructed a genetic linkage map based on retrotransposon insertion polymorphisms using a mapping population derived from a cross between ‘Purple Sweet Lord’ (PSL) and ‘90IDN-47’ cultivars. High-throughput sequencing and subsequent data analyses identified many Rtsp-1 retrotransposon insertion sites, and their allele dosages (simplex, duplex, triplex, or double-simplex) were determined based on segregation ratios in the mapping population. Using a pseudo-testcross strategy, 43 and 47 linkage groups were generated for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively. Interestingly, most of these insertions (~90%) were present in a simplex manner, indicating their utility for linkage map construction in polyploid species. Additionally, our approach led to savings of time and labor for genotyping. Although the number of markers herein was insufficient for map-based cloning, our trial analysis exhibited the utility of retrotransposon-based markers for linkage map construction in sweetpotato.

Keywords: sweetpotato, polyploidy, linkage map, pseudo-testcross, retrotransposon, high-throughput sequencing

Introduction

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam., Convolvulaceae) is one of the world’s most important crops, with an annual production of 103,145,500 tons and a harvested area of 8,087,115 hectares in 2012 (FAO; http://www.fao.org/home/en/), and is cultivated extensively in developing countries. Sweetpotato is highly nutritious, containing abundant vitamins C and A, calcium, potassium, folate, and β-carotene. The plant is also used for a wide variety of purposes, including food, processed products, animal feed, and as a source of alcohol, starch, flour, and pigments (β-carotene and anthocyanin). To fulfill these diverse use requirements, a number of sweetpotato cultivars and lines have been bred in recent years. However, sweetpotato is a highly heterozygous, outcrossing polyploid species with a large number of chromosomes (2n = 6x = 90), which complicates its genetic and linkage analyses. In addition, no whole genome sequence for the species is available, which increases the difficulty of developing molecular markers and conducting map-based gene cloning.

Only five papers to date have reported on the construction of linkage maps in sweetpotato, and these maps have been based on analyses of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), simple sequence repeat (SSR), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Cervantes-Flores et al. 2008, Kriegner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Ukoskit and Thompson 1997, Zhao et al. 2013). Sweetpotato has been characterized as an allohexaploid (Jones 1965, Magoon 1970, Ting and Kehr 1953, Sinha and Sharma 1992). Shiotani and Kawase (1989) proposed the genome constitution of sweetpotato as B1B1B2B2B2B2 based on the occurrence of frequent formation of tetravalents and hexavalents. However, recent reports have suggested that sweetpotato is an autohexaploid based on the segregation ratio of molecular markers (RAPD, SSR, and AFLP) from a genetic linkage analysis (Cervantes-Flores et al. 2008, Kriegner et al. 2003, Ukoskit and Thompson 1997, Zhao et al. 2013). In addition, these reports indicated that some preferential pairing occurs based on distorted segregation in some markers of different dosages in sweetpotato. Thus, recent studies have supported the hypothesis that the genome structure of sweetpotato is mainly autohexaploid with some preferential pairing. All linkage maps previously constructed in sweetpotato have utilized a two-way pseudo-testcross method employing F1 progeny. With this method, two separate linkage maps for each parent are constructed based on the expected segregation ratios of markers in the mapping progeny. In hexaploid mapping progeny, several variations in segregation ratio have been detected based on allele dosage (simplex, duplex, or triplex) and affected by cytological characteristics (autohexaploid, tetradiploid, or allohexaploid) (Table 1) (Jones 1967). Of these markers, only simplex markers show a simple segregation ratio (1 : 1) for any cytological characteristic (Table 1), indicating their utility as molecular markers for linkage map construction. Previous studies have employed simplex markers to construct a framework map and then inserted duplex, triplex, and double-simplex markers into the map (Cervantes-Flores et al. 2008, Kriegner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Ukoskit and Thompson 1997, Zhao et al. 2013). Thus, obtaining a number of simplex markers is important for linkage map construction.

Table 1.

The expected segregation ratio (presence : absence) of a dominant marker in a testcross of hexaploid for three hypothetical polyploidy types (Jones 1967). A and a represent dominant and recessive alleles, respectively

| Marker dose | Autohexaploid (hexasomic) | Tetradiploid (tetradisomic, tetrasomic, disomic) | Allohexaploid (disomic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplex | Aaaaaa 1 : 1 | Aa aaaa 1 : 1 | Aa aa aa 1 : 1 |

| aaaa Aa 1 : 1 | |||

| Duplex | AAaaaa 4 : 1 | AAaa aa 5 : 1a | Aa Aa aa 3 : 1 |

| Aaaa Aa 3 : 1b | AA aa aa 1 : 0 | ||

| aaaa AA 1 : 0c | |||

| Triplex | AAAaaa 19 : 1 | AAAa aa 1 : 0 | Aa Aa Aa 7 : 1 |

| AAaa Aa 11 : 1 | AA Aa aa 1 : 0 | ||

| Aaaa AA 1 : 0 | |||

| Quadruplex | AAAAaa 1 : 0 | AAAA aa 1 : 0 | AA Aa Aa 1 : 0 |

tetrasomic inheritance.

tetradisomic inheritance.

disomic inheritance.

Retrotransposons are a type of transposable element (TE) and represent the majority of DNA in higher plant genomes (Fechotte et al. 2002, Kumar and Benettzen 1999, Levin and Moran 2011). As many retrotransposon insertions are dispersed throughout the genome and are genetically inherited, insertion polymorphisms among crop cultivars have been used to develop molecular markers for phylogenetic analysis and genetic diversity studies (Kalendar 2011, Kalendar et al. 2011, Kumar and Hirochika 2001, Poczai et al. 2013, Schulman et al. 2004). Several molecular markers based on PCR amplification of retrotransposon insertions, such as inter-retrotransposon amplification polymorphism (IRAP), retrotransposon microsatellite amplification polymorphism (REMAP), and sequence-specific amplified polymorphism (S-SAP), can be employed as dominant markers (Antonius-Klemola et al. 2006, Belyayev et al. 2010, Kalendar et al. 1999, Konovalov et al. 2010, Lou and Chen 2007, Melnikova et al. 2012, Nasri et al. 2013, Petit et al. 2010, Smýkal et al. 2011, Syed et al. 2005, Waugh et al. 1997). Moreover, newly inserted copies are thought to exist primarily as simplex alleles in polyploid species because those new insertions should randomly integrate into one of the homologous chromosomes. Rtsp-1 has been identified as an active retrotransposon family in sweetpotato (Tahara et al. 2004) and appears to have high insertional polymorphism among modern sweetpotato cultivars (Monden et al. 2013). In addition, our recent research has shown that high-throughput sequencing of Rtsp-1 insertion sites achieves efficient DNA fingerprinting even without whole genome sequence information (Monden et al. 2014c). Constructing a sequencing library through PCR amplification of Rtsp-1 insertion sites in a number of cultivars and subsequent data analyses yielded 76,912 genotyping data points (2,024 retrotransposon insertion loci for 38 cultivars) with one run of an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Monden et al. 2014c). Thus, high-throughput sequencing of active retrotransposon insertions in a mapping population is considered to be effective for linkage map construction.

In the present study, we constructed a linkage map based on Rtsp-1 insertion polymorphisms in sweetpotato. High-throughput sequencing and subsequent data analyses revealed a number of insertion sites in F1 progeny derived from the cultivars ‘Purple Sweet Lord’ (PSL) and 90IDN-47. We determined the allele dosages of these insertion sites according to their segregation ratios in the mapping population. Interestingly, we observed that most of the insertion sites (~90%) existed as simplex alleles, indicating their applicability as molecular markers for generating linkage maps in polyploid species.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and sample preparation

The F1 mapping population originated from a cross between two sweetpotato cultivars, ‘Purple Sweet Lord’ (PSL) and ‘90IDN-47’. PSL is one of the most famous purple sweetpotato cultivars in Japan and possesses numerous desirable characteristics, such as high yield, a high anthocyanin content, and good eating quality. Although PSL is widely grown in Japan, this cultivar is highly susceptible to infection by the pathogen Streptomyces ipomoeae. Showing resistance to this pathogen, 90IDN-47 is an Indonesian cultivar. To develop the mapping population, a cross was conducted using PSL as the female parent and 90IDN-47 as the male parent. A total of 98 F1 plants were used for the construction of a genetic linkage map in the present study. Genomic DNA was extracted from the parental cultivars and F1 progeny using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit and following the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN Inc, Germany).

Construction of sequencing library

An Illumina MiSeq sequencing library was constructed through PCR amplification of Rtsp-1 insertion sites (Supplemental Fig. 1). After the extracted DNA was fragmented using a g-TUBE (Covaris), forked adapters were ligated to the DNA fragments. The forked adapters were prepared by annealing two different oligos (Forked_Type1 and Forked_ Com) (Supplemental Table 1). Primary PCR amplification was performed with an Rtsp-1-specific (Rtsp-1_ppt) and adapter-specific (AP2) primer combination using the adapter-ligated DNA as the template. The PCR cycling program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 80°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 15 min. For nested PCR amplification, primers were customized to contain P5 or P7 sequences (Illumina) for hybridization on the sequencing flow cell and several barcodes for multiplex sequencing. Thus, the Rtsp-1-specific primers (D501–D510) consisted of a P5 sequence, one of 10 barcode sequences, and the Rtsp-1 end sequence, while the adapter-specific primers (D701–D712) consisted of a P7 sequence, one of 12 barcode sequences, and an adapter sequence; this arrangement permits a maximum of 120 samples (=10*12) for multiplex sequencing (Supplemental Table 1). The primer combinations of each sample are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Nested PCR amplification was performed with Rtsp-1–specific (one from D501–D510) and adapter-specific (one from D701–D712) primer sets using primary PCR products as the template (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The PCR cycling program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 80°C for 30 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 15 min. These PCR products were size-selected (400–600 bp) on agarose gels and purified with a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). The purified products were quantified with a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and the size selection was confirmed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Finally, equal amounts of these products were pooled to prepare a MiSeq sequencing library. MiSeq sequencing was conducted using an MS-102-2002 MiSeq Reagen Kit v2 (300 cycles) (Illumina). MiSeq sequencing which used the Rtsp-1 and adapter end sequences as custom primers yielded 150 bp of paired-end reads of the Rtsp-1 inserted site at each end (Supplemental Fig. 1). The sequences of the primers and adapters are listed in Supplemental Table 1. The MiSeq reads obtained in the present study were submitted to DDBJ (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) under Accession No. DRA002270.

Data analyses

The MiSeq sequence reads were classified by line or cultivar based on the dual barcodes. The number of reads for each cultivar is shown in Supplemental Table 2. We analyzed these reads according to the procedures of our previous study (Monden et al. 2014b, 2014c) using Maser, which is the pipeline execution system of the Cell Innovation Program at the National Institute of Genetics (http://cell-innovation.nig.ac.jp/index_en.html). The procedures for data analyses are briefly described below. First, the paired-end reads were filtered out for invalid dual barcodes; if a read had an erroneous or undetermined barcode on either side, the entire read was discarded. The reads were then trimmed to 50 bp in length from the Rtsp-1 junction, and adapter removal with cutadapt (https://code.google.com/p/cutadapt/) and quality filtering based on the quality value (QV) for all base calls ≥20, were conducted. After the outliers were filtered by trimming them to a specific length that contained most of the sequences, reads shorter than this length were filtered out. The reads with ≥10 identical sequences were collapsed into a single sequence in FASTA format, and reads with <10 identical sequences were excluded from further analyses. Clustering analyses to identify Rtsp-1 insertion sites were performed with the BLAT self-alignment program (Kent 2002) using the following parameter settings: -tileSize = 8, -minMatch = 1, -minScore = 10, -repMatch = −1, and -oneOff = 2. To investigate the similarity of the sequences in the FASTA file, all-to-all comparison analysis was conducted, and clusters were built based on sequence similarities with the results of the pairwise alignments. In each cluster, a multiple sequence alignment was performed to reveal sequence similarity using the ClustalW program (Larkin et al. 2007). Our results showed that the sequences to be aligned in each cluster were very similar to each other (identity of more than 90%). The sequence with the highest read number in each cluster was selected as the representative sequence. These analyses produced a number of clusters and non-clustered sequences with ≥10 reads, each indicating an individual insertion site where an Rtsp-1 copy was inserted in at least one line or cultivar. We summarized the total number of reads and the number of reads for each cluster in all lines and cultivars. However, assigning insertion sites to cultivars would probably have caused some errors, because sequence errors in the barcode sequence may have allocated the reads to an incorrect cultivar. In addition, the reads with sequencing error might be mistakenly clustered. This erroneous assignment and clustering would have resulted in a very small number of reads in some clusters. Thus, we set a critical value for determining the presence of Rtsp-1 insertions, i.e., if the reads for a cultivar at a specific insertion site comprised <0.01% of the entire reads for that cultivar, we assumed that the retrotransposon was absent from that site. We have performed retrotransposon insertion site analysis using the same pipeline for other sweetpotato groups and wheat (Monden et al. 2014b, 2014c). In these analyses, we set several critical values, such as 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01%, for determining the presence or absence of insertion sites, and examined the results by PCR targeting the insertion sites. The critical value of 0.01% was found to best suit the results by PCR. Thus, we used 0.01% as the critical value for determining the presence or absence of Rtsp-1 insertion sites in the present study. These processes produced genotyping information for the presence (1) or absence (0) of Rtsp-1 insertion in both parents and the 98 F1 progeny. Insertions that were detected in either or both of the parents were utilized as molecular markers for linkage map construction.

Linkage map construction

In outcrossing heterozygous species, such as sweetpotato, a two-way pseudo-testcross strategy has been applied to construct linkage maps, as developed by Grattapaglia and Sederoff (1994). The dominant marker dosages in hexaploid sweetpotato can be determined by investigating the segregation ratio (presence to absence) in the mapping progeny for three hypothetical polyploidy types: (a) simplex markers, present in only a single copy in one parent and segregating in a 1 : 1 (presence : absence) ratio regardless of the polyploidy type; (b) duplex markers, present in two copies in one parent and segregating in 4 : 1 (hexasomic), 5 : 1 (tetrasomic), or 3 : 1 (disomic or tetradisomic) ratio; and (c) triplex markers, present in three copies in one parent and segregating in 19 : 1 (hexasomic), 11 : 1 (tetradisomic), or 7 : 1 (disomic) ratio (Table 1) (Jones, 1967). In the present study, we assumed that sweetpotato was autohexaploid and tested the segregation ratio of the presence to absence of the Rtsp-1 insertions in the progeny using χ2 goodness of fit (α = 0.01). We used JoinMap 4.1 software to construct a linkage map using a maximum likelihood (ML) mapping algorithm (Kyazma). Markers that were polymorphic between parents were grouped into separate sets according to their parental derivation and analyzed independently to construct a framework map. Simplex markers behave the same in diploids as in polyploids and can be mapped with standard methods. At first, the simplex markers were used to construct a framework map for each parent, and secondly, the double-simplex markers, which are present in a single copy in both parents with a segregation ratio of 3 : 1 in the progeny, were introduced into the framework maps. The ratio of marker segregation was calculated according to χ2 goodness of fit (α = 0.01). Markers showing significantly distorted segregation were excluded from the map construction. These steps were conducted using a CP population type with default options in the ML mapping. A LOD score of 5 was set as the linkage threshold for grouping and ordering of markers.

Results

MiSeq sequencing and data analyses

A total of 16,967,012 paired-end reads of 150 bp were obtained from one run of the MiSeq sequencing platform. Of those reads, 16,557,182 contained the correct barcodes on both sides (P5 and P7). The remaining reads had erroneous or undetermined barcodes on either side (Table 2) and were excluded from further data analyses. The numbers of reads for each cultivar are shown in Supplemental Table 2. After trimming and filtering (QV ≥20), 7,552,515 reads remained (Table 2). Those reads were used for clustering analysis with the BLAT self-alignment program (Kent 2002), which produced 792 clusters or non-clustered single sequences with ≥10 reads that represented Rtsp-1 insertion sites (Table 2). We conducted genotyping (presence or absence) for each insertion site and calculated the total number of insertion sites for each line or cultivar. To investigate the reliability of the insertions predicted from the data analyses, several insertions were randomly selected for experimental confirmation by PCR (Supplemental Fig. 2). The PCR polymorphic bands were completely consistent with the genotyping results (absence and presence) predicted from the data analyses in randomly selected lines, which indicates the high reliability of our data analyses. We used two plants of PSL and 90IDN-47 cultivars for MiSeq sequencing and the data analyses (Supplemental Table 2). The numbers of Rtsp-1 insertion sites identified in our data analyses were 236 and 232 for PSL plants, and 238 and 237 for 90IDN-47 plants. Thus, the numbers of Rtsp-1 insertion sites were almost same between PSL and 90IDN047 parental cultivars. The average number of Rtsp-1 insertion sites in the F1 mapping populations was 233.5, with a range from 202 to 261. Thus, the numbers of Rtsp-1 insertion sites in the F1 mapping populations were close to those of parental cultivars. Interestingly, several new insertion sites appeared in the F1 mapping populations, which were not present in either two parental cultivars. However, an extremely few number of reads supported those insertion sites, which indicated that some errors of sequencing or clustering might occur at those putative new insertion sites (data not shown). For linkage map construction, we utilized the insertion sites that were present in the PSL and/or 90IDN-47 cultivars and were segregated in the F1 mapping populations.

Table 2.

Summary of reads in the data analyses

| Analysis | No. of reads | Ratio (%) | No. of collapsed reads (more than 10) | No. of clusters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | 16,967,012 | – | – | – |

| Validation of barcode | 16,557,182 | 97.6 | – | – |

| Adaptor removal | 16,436,002 | 96.9 | 77,876 | – |

| Trimming to 50 bp | 16,436,002 | 96.9 | 42,864 | – |

| QV (≥20) filtering | 11,254,201 | 66.3 | 31,296 | – |

| Outlier filtering | 7,552,515 | 44.5 | 15,705 | – |

| BLAT clustering | – | – | – | 792 |

Marker scoring

The total number of markers scored for PSL was 154, of which 133 (86.4%), 17 (11%), and 2 (1.3%) were simplex, duplex, and triplex markers under the assumption of autohexaploidy, respectively, while 158 markers were scored for 90IDN-47, of which 140 (88.6%), 10 (6.3%), and 1 (0.6%) were simplex, duplex and triplex markers, respectively, according to χ2 goodness of fit (α = 0.01) (Table 3). The results showed that only two and seven markers did not statistically fit the autohexaploid type segregations for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively (Table 3). Those simplex markers were used to construct the framework linkage map in each parent. In addition, the number of markers scored for both parents was 75, of which 41 (54.7%) were considered to be double-simplex markers (Table 3). The segregation ratios of the remaining 34 markers were not fitted to 3 : 1, according to χ2 goodness of fit (α = 0.01). The marker sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of segregation ratios of markers developed in the present study (α = 0.01)

| Genotype | No. of markers | Allele dosage | No. of markers* (α = 0.01) | % | Segregation ratio (presence : absence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSL | 154 | Simplex | 133 | 86.4 | 1 : 1 |

| Duplex | 17 | 11.0 | 4 : 1 | ||

| Triplex | 2 | 1.3 | 19 : 1 | ||

|

| |||||

| 90IDN-47 | 158 | Simplex | 140 | 88.6 | 1 : 1 |

| Duplex | 10 | 6.3 | 4 : 1 | ||

| Triplex | 1 | 0.6 | 19 : 1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Both parents | 75 | Double-Simplex | 41 | 54.7 | 3 : 1 |

Linkage map construction

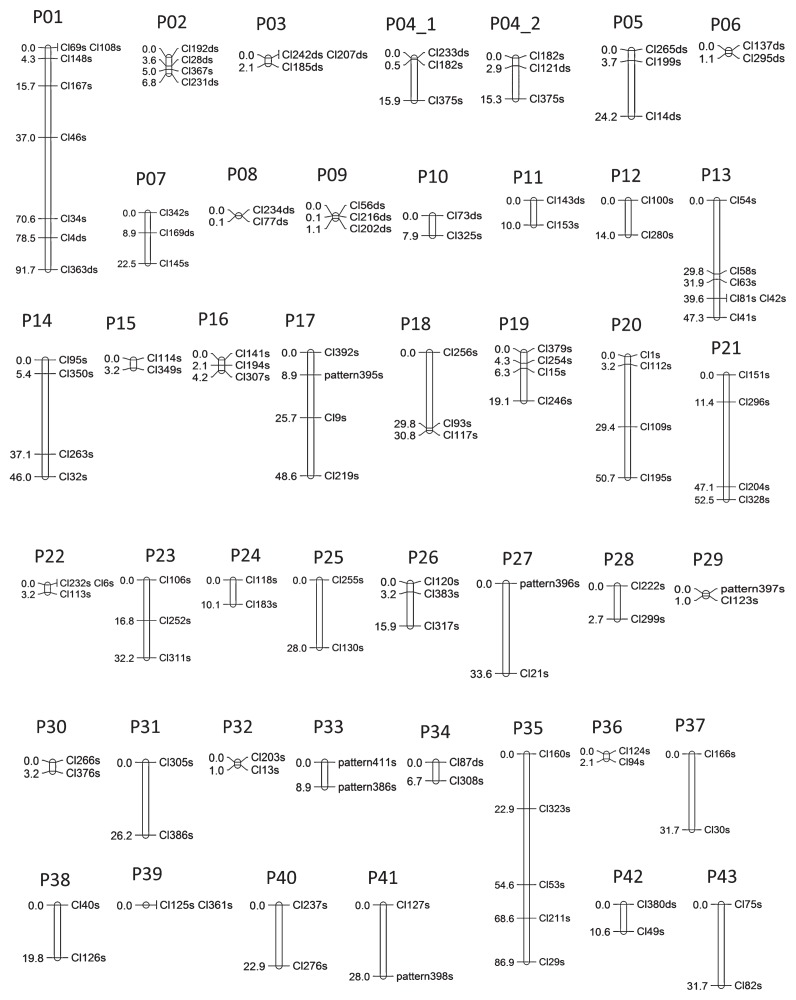

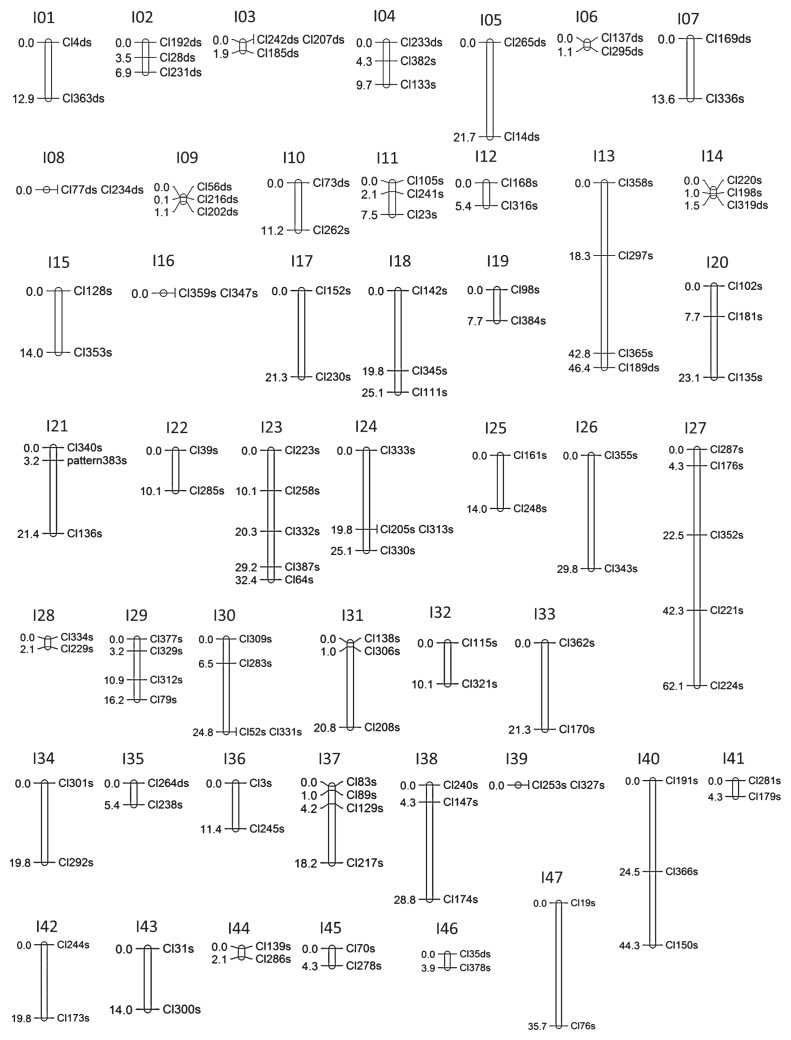

The genetic linkage map for each parent was constructed at an LOD score of 5.0 using JoinMap 4.1 software (Kyazma). The molecular markers were grouped into 43 and 47 linkage groups for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively (Table 4, Figs. 1 and 2). In the linkage map for PSL, the entire length was estimated as 931.5 cM, with an average distance between markers of 11.6 cM and an average length per linkage group of 21.2 cM. The number of mapped markers totaled 124, ranging from 2 to 8 markers per linkage group (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 4). In the map for 90IDN-47, the entire length was estimated as 734.3 cM, with an average distance between markers of 9.8 cM and an average length per linkage group of 15.6 cM. The number of mapped markers totaled 122, ranging from 2 to 5 per linkage group (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 4). Double-simplex markers were used to investigate the homology of the linkage groups between both parent maps. A total of 20 double-simplex markers revealed homologous relationships between 10 linkage groups of PSL (P01–P10) and 10 of 90IDN-47 (I01–I10) (Figs. 1 and 2, and Supplemental Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Summary of linkage maps constructed in the present study

| Parent cultivars | PSL | 90IDN-47 |

|---|---|---|

| No. of linkage groups | 43 | 47 |

| Total length (cM) | 931.5 | 734.3 |

| Average length of linkage groups (cM) | 21.2 | 15.6 |

| Average distance between markers (cM) | 11.6 | 9.8 |

| Min. number of markers in linkage groups | 2 | 2 |

| Max. number of markers in linkage groups | 8 | 5 |

| Min. length of linkage groups (cM) | 0.0* | 0.0* |

| Max. length of linkage groups (cM) | 91.7 | 46.4 |

Although the linkage groups with minimum length contain more than two independent markers, recombination was not observed in our F1 mapping populations. Thus, the markers in these linkage groups were considered to be closely linked.

Fig. 1.

Linkage map of ‘PSL’ based on Rtsp-1 markers (P01–P43). The linkage groups were integrated with JoinMap 4.1 at an LOD of 5.0. The name of each marker is derived from the name of the insertion site (Cl* or pattern) and s (representing simplex marker) or ds (representing double-simplex). The number corresponding to each marker indicates the genetic distance between markers (cM). Of these linkage groups, P01–P10 are homologous to I01–I10.

Fig. 2.

Linkage map for ‘90IDN-47’ based on Rtsp-1 markers (I01–I47). The linkage groups were integrated with JoinMap 4.1 at an LOD of 5.0. The name of each marker is derived from the name of the insertion site (Cl* or pattern) and s (representing simplex marker) or ds (representing double-simplex). The number corresponding to each marker indicates the genetic distance between markers (cM). Of these linkage groups, I01–I10 are homologous to P01–P10.

Discussion

In the present study, we constructed a linkage map based on Rtsp-1 retrotransposon insertion polymorphisms in sweetpotato. Five studies to date have constructed genetic linkage maps in sweetpotato using RAPD, SSR, and AFLP markers (Table 5) (Cervantes-Flores et al. 2008, Kriegner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Ukoskit and Thompson 1997, Zhao et al. 2013); the present study is thus the first to generate a linkage map based on retrotransposon insertion sites. To identify the comprehensive Rtsp-1 insertion sites in the two parent cultivars and F1 progeny, we employed the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform, which produced over 16 million reads within 2–3 weeks. A large number of reads were obtained in one run of the MiSeq sequencer, and subsequent data analyses determined the Rtsp-1 insertions in the mapping population according to the methods of our previous study. Thus, our approach is considered to be time- and labor-efficient for developing genetic markers and linkage maps.

Table 5.

Summary of the segregation ratios of molecular markers analyzed in sweetpotato

| Types of markers | Parent cultivars | No. of markers | No. of simplex markers | % | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD | Vardaman | 102 | 76 | 74.5 | Ukoskit and Thompson (1997) |

| Regal | 94 | 67 | 71.3 | ||

|

| |||||

| AFLP | Bikilamaliya | 641 | 410 | 64.0 | Kriegner et al. (2003) |

| Tanzania | 808 | 519 | 64.2 | ||

|

| |||||

| AFLP | Beauregard | 1751 | 1303 | 74.4 | Cervantes-Flores et al. (2008) |

| Tanzania | 1944 | 1511 | 77.7 | ||

|

| |||||

| SRAP | Luoxushu 8 | 770 | 446 | 57.9 | Li et al. (2010) |

| Zhengshu 20 | 523 | 325 | 62.1 | ||

|

| |||||

| AFLP and SSR | Xushu 18 | 2772 | 1204 | 43.4 | Zhao et al. (2013) |

| Xu 781 | 2850 | 1298 | 45.5 | ||

|

| |||||

| Retrotransposon based | PSL | 154 | 133 | 86.4 | The present study |

| 90IDN-47 | 158 | 140 | 88.6 | ||

Interestingly, the Rtsp-1–based molecular markers showed an extremely high proportion of simplex markers (~90%) in comparison with other molecular marker methods used in sweetpotato (Table 5). In the hexaploid mapping progeny, simplex, duplex, and triplex alleles showed polymorphism (alleles with higher doses showed no polymorphism). Due to the simple segregation ratio of simplex markers regardless of polyploidy type (Table 1), this type of marker is the most useful for the construction of framework maps in polyploidy species. Thus, retrotransposon-based molecular markers are more effective than any other marker types and should facilitate the construction of linkage maps in polyploid species.

A large number of retrotransposon families exist in higher plant genomes. The present study focused on only one retrotransposon family, Rtsp-1, which generated an average of 200–250 insertion sites per line or cultivar. In our previous study, the average number of Rtsp-1 insertion sites was 257.5 among 38 modern sweetpotato cultivars (Monden et al. 2014c), which indicated that the number of Rtsp-1 insertion sites is considered to range from 200 to 250 in the genomes of most sweetpotato cultivars. Using the Rtsp-1 insertion sites in PSL, 90IDN-47, and F1 mapping populations, we constructed linkage maps which contained 124 and 122 mapped markers for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2). Sweetpotato is a hexaploid species (2n = 6x = 90) with an estimated genome size of 2200–3000 Mb. Thus, a large number of molecular markers are required for map-based gene cloning. So far, only five reports have constructed linkage maps in sweetpotato (Cervantes-Flores et al. 2008, Kriegner et al. 2003, Li et al. 2010, Ukoskit and Thompson 1997, Zhao et al. 2013). Kriegner et al. (2003) constructed linkage maps with a total of 632 and 435 AFLP markers, which produced 90 and 80 linkage groups for Tanzania Bikilamaliya parental cultivars, respectively. Cervantes-Flores et al. (2008) constructed linkage maps of Tanzania and Beauregard cultivars, which consisted of 86 and 90 linkage groups with 1166 and 960 AFLP markers, respectively. More recently, Zhao et al. (2013) constructed the highest density linkage maps, which contained 2,077 and 1,954 markers for Xushu 18 and Xu 781 parental cultivars, respectively. In their report, the linkage map for Xushu 18 covered 8,184.5 cM and generated 90 linkage groups, and that for Xu 781 covered 8,151.7 cM and generated 90 linkage groups. Thus, several thousands of markers are required to have 90 complete linkage groups, which is in agreement with the actual number of chromosomes in sweetpotato. Considering this, the marker numbers (124 and 122 markers for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively) in our maps are by far insufficient for the map-based cloning of genes. Indeed, our linkage maps cover only 43 and 47 linkage groups for PSL and 90IDN-47, respectively. In addition, the genetic positions of several molecular markers (Cl233ds and Cl121ds) grouped on the same linkage group (P04) could not be determined in the PSL linkage map, and the markers were therefore placed on separate linkage groups (P04_1 and P04_2) (Fig. 1). This situation may have been due to the lack of closely linked markers caused by the small number of mapped markers in our linkage map. Obviously, many additional markers are required to cover all 90 linkage groups for QTL mapping. However, we have recently screened long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon families showing high insertion polymorphism among cultivars in several crop species via an efficient, high-throughput sequencing platform (Monden et al. 2014a). We are currently identifying those families in sweetpotato; once those families are identified, their insertion polymorphisms may easily be applied as molecular markers. Thus, combining several families with high copy numbers should provide a large number of loci within the genome.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the usefulness and efficiency of retrotransposon-based molecular markers for the construction of linkage maps in polyploid species: a higher proportion of simplex markers, and time and labor savings by high-throughput sequencing. We expect that a higher-density linkage map will be generated based on the insertion polymorphisms of several retrotransposon families combined with other molecular markers, thereby promoting map-based cloning of genes in sweetpotato.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to Takako Nabeshima for her assistance in performing the experiments. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics-based Technology for Agricultural Improvement, SFC-3003).

Literature Cited

- Antonius-Klemola, K., Kalendar, R. and Schulman, A.H. (2006) TRIM retrotransposons occur in apple and are polymorphic between varieties but not sports. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyayev, A., Kalendar, R., Brodsky, L., Nevo, E., Schulman, A. and Raskina, O. (2010) Transposable elements in a marginal plant population: temporal fluctuations provide new insights into genome evolution of wild diploid wheat. Mob. DNA 1: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Flores, J.C., Yencho, G.C., Kriegner, A., Pecota, K.V., Faulk, M.A., Mwanga, R.O.M. and Sosinski, B.R. (2008) Development of a genetic linkage map and identification of homologous linkage groups in sweet potato using multiple-dose AFLP markers. Mol. Breed. 21: 511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., Jiang, N. and Wessler, S.R. (2002) Plant transposable elements: where genetics meets genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattapaglia, D. and Sederoff, R. (1994) Genetic linkage maps of Eucalyptus grandis and Eucalyptus urophylla using a pseudo-testcross: mapping strategy and RAPD markers. Genetics 137: 1121–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. (1965) Cytological observations and fertility measurements of sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.]. Proc. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 86: 527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. (1967) Theoretical segregation ratios of qualitatively inherited characters for hexaploid sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Technical Bulletin No. 1368. Agricultural Research Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture in cooperation with Georgia Agricultural Experiment Stations, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar, R., Grob, T., Regina, M., Suoniemi, A. and Schulman, A. (1999) IRAP and REMAP: two new retrotransposon-based DNA fingerprinting techniques. Theor. Appl. Genet. 98: 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar, R. (2011) The use of retrotransposon-based molecular markers to analyze genetic diversity. Ratar. Povrt. 48: 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar, R., Flavell, A.J., Ellis, T.H.N., Sjakste, T., Moisy, C. and Schulman, A.H. (2011) Analysis of plant diversity with retrotransposon-based molecular markers. Heredity 106: 520–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W.J. (2002) BLAT—The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Res. 12: 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konovalov, F.A., Goncharov, N.P., Goryunova, S., Shaturova, A., Proshlyakova, T. and Kudryavtsev, A. (2010) Molecular markers based on LTR retrotransposons BARE-1 and Jeli uncover different strata of evolutionary relationships in diploid wheats. Mol. Genet. Genomics 283: 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegner, A., Cervantes, J.C., Burg, K., Mwanga, R.O.M. and Zhang, D. (2003) A genetic linkage map of sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] based on AFLP markers. Mol. Breed. 11: 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. and Bennetzen, J.L. (1999) Plant retrotransposons. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33: 479–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. and Hirochika, H. (2001) Applications of retrotransposons as genetic tools in plant biology. Trends Plant Sci. 6: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N.P., Chenna, R., McGettigan, P.A., McWilliam, H., Valentin, F., Wallace, I.M., Wilm, A., Lopez, R.et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23: 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, H.L. and Moran, J.V. (2011) Dynamic interactions between transposable elements and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12: 615–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.-X., Liu, Q.-C., Wang, Q.-M., Zhang, L.-M., Zhai, H. and Liu, S.-Z. (2010) Establishment of molecular linkage maps using SRAP markers in sweet potato. Acta Agron. Sin. 36: 1286–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Q. and Chen, J. (2007) Ty1-copia retrotransposon-based SSAP marker development and its potential in the genetic study of cucurbits. Genome 810: 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoon, M.L., Krishnan, R. and Vijaya Bai, K. (1970) Cytological evidence on the origin of sweet potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 40: 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikova, N.V., Kudryavtseva, A.V., Speranskaya, A.S., Krinitsina, A.A., Dmitriev, A.A., Belenikin, M.S., Upelniek, V.P., Batrak, E.R., Kovaleva, I.S. and Kudryavtsev, A.M. (2012) The FaRE 1 LTR-retrotransposon based SSAP markers reveal genetic polymorphism of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) cultivars. J. Agric. Sci. 4: 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Monden, Y., Yamamoto, A. and Tahara, M. (2013) Development of DNA markers for anthocyanin content purple sweet potato using active retrotransposon insertion polymorphisms. DNA Polymorphism (DNA Takei) 21: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Monden, Y., Fujii, N., Yamaguchi, K., Ikeo, K., Nakazawa, Y., Waki, T., Hirashima, K., Uchiyama, Y. and Tahara, M. (2014a) Efficient screening of long terminal repeat retrotransposons that show high insertion polymorphism via high-throughput sequencing of the primer binding site. Genome 57: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monden, Y., Takai, T. and Tahara, M. (2014b) Characterization of a novel retrotransposon TriRe-1 using nullisomic-tetrasomic lines of hexaploid wheat. Sci. Rep. Facul. Agr. Okayama University 103: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Monden, Y., Yamamoto, A., Shindo, A. and Tahara, M. (2014c) Efficient DNA fingerprinting based on the targeted sequencing of active retrotransposon insertion sites using a bench-top high-throughput sequencing platform. DNA Res. 21: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, S., Abdollahi Mandoulakani, B., Darvishzadeh, R. and Bernousi, I. (2013) Retrotransposon insertional polymorphism in Iranian bread wheat cultivars and breeding lines revealed by IRAP and REMAP markers. Biochem. Genet. 51: 927–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit, M., Guidat, C., Daniel, J., Denis, E., Montoriol, E., Bui, Q.T., Lim, K.Y., Kovarik, A., Leitch, A.R., Grandbastien, M.et al. (2010) Mobilization of retrotransposons in synthetic allotetraploid tobacco. New Phytol. 186: 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poczai, P., Varga, I., Laos, M., Cseh, A., Bell, N., Valkonen, J.P. and Hyvönen, J. (2013) Advances in plant gene-targeted and functional markers: a review. Plant Methods 9: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, A.H., Flavell, A.H. and Ellis, T.H.N. (2004) The application of LTR retrotransposons as molecular markers in plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 260: 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiotani, I. and Kawase, T. (1989) Genomic structure of the sweet potato and hexaploids in Ipomoea trifida (HBK) DON. Jpn. J. Breed. 39: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, S. and Sharma, S.N. (1992) Taxonomic significance of karyomorphology in Ipomoea spp. Cytologia 57: 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Smýkal, P., Bačová-Kerteszová, N., Kalendar, R., Corander, J., Schulman, A.H. and Pavelek, M. (2011) Genetic diversity of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) germplasm assessed by retrotransposon-based markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 1385–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, N.H., Sureshsundar, S., Wilkinson, M.J., Bhau, B.S., Cavalcanti, J.J.V. and Flavell, A.J. (2005) Ty1-copia retrotransposon-based SSAP marker development in cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara, M., Aoki, T., Suzuka, S., Yamashita, H., Tanaka, M., Matsunaga, S. and Kokumai, S. (2004) Isolation of an active element from a high-copy-number family of retrotransposons in the sweet potato genome. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272: 116–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting, Y.C. and Kehr, A.E. (1953) Meiotic studies in the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.). J. Hered. 44: 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ukoskit, K. and Thompson, P.G. (1997) Autopolyploidy versus allopolyploidy and low-density randomly amplified polymorphic DNA linkage maps of sweet potato. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 122: 822–828. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, R., McLean, K., Flavell, A.J., Pearce, S.R., Kumar, A., Thomas, B.B. and Powell, W. (1997) Genetic distribution of Bare-1-like retrotransposable elements in the barley genome revealed by sequence-specific amplification polymorphisms (S-SAP). Mol. Gen. Genet. 253: 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N., Yu, X., Jie, Q., Li, H., Li, H., Hu, J., Zhai, H., He, S. and Liu, Q. (2013) A genetic linkage map based on AFLP and SSR markers and mapping of QTL for dry-matter content in sweet potato. Mol. Breed. 32: 807–820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.