Abstract

The present study was conducted to evaluate the benefits of indeterminate growth habit in breeding to improve yield potential of Japanese soybean varieties, which exclusively have determinate growth habit. Two populations of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from crosses between determinate Japanese cultivars and indeterminate US cultivars were grown in Akita and Kyoto, and seed weight per plant (SW) and its components were compared between indeterminate and determinate RILs. The difference of SW between the two growth habits in RILs varied depending on maturation time. The SW of early indeterminate lines was significantly higher than that of early determinate ones in Akita, but not in Kyoto. Among yield components, the number of seeds per pod was constantly larger in indeterminate lines than that in determinate ones irrespective of maturation time. The number of seeds per plant and the number of pods per plant of the indeterminate lines were greater than those of the determinate lines in early maturation in Akita. These results suggest that the indeterminate growth habit is an advantageous characteristic in breeding for high yield of early maturing soybean varieties in the Tohoku region.

Keywords: growth habit, maturation time, recombinant inbred line, soybean breeding, Tohoku region, yield component

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is the most economically important leguminous seed crop and provides the majority of plant protein and oil. Especially in Japan, soybean has long been an important crop because it is used for traditional foods such as miso, natto and tofu. However, the yield of soybean in Japan has not increased for 50 years so much as that in the USA, and therefore, increasing the yield of soybean is an important breeding objective in Japan (Shimada et al. 2013).

Stem growth habit is an important key character affecting yield in soybean. Based on stem growth habits, soybeans can be classified into indeterminate growth plants (IND), semi-determinate growth plants and determinate growth plants (DET), these categories having been demonstrated to be primarily controlled by Dt1 and Dt2 loci (Bernard 1972). The stem length and leaf formation in IND continue to grow for a long period after flowering. In DET, stem growth is terminated when flowering begins or soon afterward, and semi-determinate plants show stem termination intermediate between that of IND and that of DET (Bernard 1972). TERMINAL FLOWER1 (GmTFL1) on chromosome 19 (Glyma19g37890.1) has been identified as Dt1 using transformation and virus-induced gene silencing approaches in previous reports (Liu et al. 2010, Tian et al. 2010). GmTFL1 transcripts have been shown to accumulate in shoot apical meristems during early vegetative growth in both DET and IND, but GmTFL1 transcripts are abruptly lost after flowering in DET, while remaining in IND (Liu et al. 2010). This difference results in a difference of main stem nodes and flowering periods between IND and DET.

There have been some reports about the effect of the stem growth habit on yield in soybean. Some reports have shown a higher yield of IND (Bernard 1972, Cooper and Waranyuwat 1985, Parvez et al. 1989, Robinson and Wilcox 1998, Shannon et al. 1971) and a higher yield of DET (Weaver et al. 1991), and some reports have shown that the superiority of yield of IND or that of DET depends on location and genetic background (Boerma and Ashley 1982, Cober and Tanner 1995, Foley et al. 1986, Hicks et al. 1969, McBroom et al. 1981, Ouattara and Weaver 1995, Pfeiffer and Harris. 1990, Wilcox and Frankenberger 1987). Cober and Tanner (1995) and Ouattara and Weaver (1995) have pointed out that these inconsistencies are caused by interactions for yield between stem growth habit and location and between stem growth habit and genetic background. Despite many reports about the effect of growth habit on yield, there have been few reports on the effect of the stem growth habit on yield in the field in Japan and/or Japanese soybean cultivars. Most Japanese soybean cultivars are DET and Japanese breeders have rarely selected IND as parents for breeding because IND are inferior to DET in the uniformity of seed size due to their long flowering time (Nagata 1967). However, prolonged or continued stem growth could contribute to an increase of yield. In order to evaluate the effect of the IND trait on the yield in Japan, it is necessary to investigate the effect of the introduction of the IND trait into Japanese cultivars.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between yield and the stem growth habit at two locations in Japan. In the present study, two recombinant inbred line populations (RILs) without artificial and environmental selection developed from crosses between Japanese DET cultivars and U.S. IND cultivars were used.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Two RIL populations, designated as OA-RILs and ST-RILs, were developed by the single-seed descent (SSD) method from crosses of ‘Ohsuzu’ × ‘Athow’ (PI 595926) and ‘Stressland’ (PI 593654) × ‘Tachinagaha’, respectively. ‘Athow’ [maturity group (MG) III] and ‘Stressland’ (MG IV) developed for soybean meal and vegetable oil by the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA-ARS) (Cooper et al. 1999, Wilcox and Abney 1997) were selected as standard U.S. IND cultivars. ‘Ohsuzu’ (MG III) and ‘Tachinagaha’ (MG V), which are typical Japanese varieties for food products such as tofu and boiled (cooked) beans (Miyazaki et al. 1987, Tabuchi et al. 1999), were chosen as DET varieties. Generations were advanced to F6 for the OA-RIL population and to F7 for the ST-RIL population by SSD without selection. Generations of OA-RILs used in this experiment were F9 of OA-RILs in 2009 and F10 in 2010 and that of ST-RILs was F8 in 2010. The OA-RIL population consisted of 225 lines, and that of ST-RIL comprised 250 lines.

Experimental procedures of field trails

All plant materials were grown in two locations, Akita (the Kariwano Branch of the Daisen Research Station of NARO Tohoku Region Agricultural Research Center, located at 39°32′N, 140°22′E) and Kyoto (the Experimental Farm of Kyoto University, located at 35°40′N, 139°46′E), from 2009 to 2010. An OA-RIL population was grown in Akita in 2009 and 2010, and in Kyoto only in 2010, whereas an ST-RIL population was grown in Akita and Kyoto only in 2010. The experimental field in Akita has highly humic andosol and was fertilized with 24 kg ha−1 of N, 80 kg ha−1 of P2O5 and 80 kg ha−1 of K2O before sowing. Each line or variety was planted in plots 2 to 2.4 m in length with a row spacing of 0.75 m and plant separation of 0.12 m within each row. The experimental field in Kyoto has alluvial sandy loam soil and was fertilized with 30 kg ha−1 of N, 100 kg ha−1 of P2O5 and 100 kg ha−1 of K2O before sowing. Each line or cultivar was planted in plots 1.35 m in length with a row spacing of 0.7 m and plant separation within each row of 0.15 m. Sowing dates were 19 June in 2009 for OA-RILs, 26 June in 2010 for OA-RILs and ST-RILs in Akita, whereas the sowing date was 28 June in 2010 for OA-RILs and ST-RILs in Kyoto. In 2009 and 2010, all 225 lines of OA-RILs were used in Akita, while 118 lines of ST-RILs randomly selected from the ST-RIL population were used in Akita in 2010 due to field and labor limitations. Similarly, in Kyoto in 2010, 60 lines were randomly selected from both OA-RILs and ST-RILs. Sixty selected lines of ST-RILs grown in Kyoto were included in the 118 lines selected from ST-RILs in Akita. Plots at each location were arranged according to a randomized complete block design with two replications. All plants with the exception of two at both ends of each row were harvested and seeds were bulked.

Measurement of agronomic characteristics

Stem termination of each line was presumed by the genotype of GmTFL1 beforehand and confirmed by visual inspection of main stem growth and termination after flowering (Bernard 1972). Nucleotide sequences of PCR products of GmTFL1 alleles in ‘Ohsuzu’, ‘Tachinagaha’, ‘Athow’ and ‘Stressland’ amplified by three primer pairs (GmTfl1-frag1, GmTfl1-frag2 and GmTfl1-frag3) were determined using an ABI3730XL Genetic Analyzer with BigDye terminator ver 3.1 (Applied Biosystems) (Tian et al. 2010). GmTFL1 genotypes of F6 plants in OA-RILs and F7 plants in ST-RILs were analyzed by distinguishing the length polymorphism of PCR products amplified by a primer pair of Dt1Int (5′-TATCTCTTCTCTTCTTATTCC-3′ and 5′-TACCGTGTGACCATGATTACAG-3′) using AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The initial 10-min denaturation at 95°C was followed by 35 cycles of 30-s denaturation at 95°C, 30-s annealing at 50°C and 1-min extension at 72°C. A final 7-min extension at 72°C completed the program. The amplified products were separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel.

In addition, flowering time (FT), maturation time (MT), number of pods per plant (NPP), number of seeds per pod (SPP), number of seeds per plant (NSP), 100-seed weight (HSW), seed weight per plant (SW), protein content (PRO) and oil content (OIL) of RILs were evaluated. FT was defined as the number of days from sowing to flowering of 50% of the plants in a plot, whereas MT was defined as the number of days from sowing to maturation of 80% of the plants in the plot (Yamada et al. 2012). Pods having seeds were counted for five plants in Akita and three plants in Kyoto in each plot to calculate NPP. The number of potential seeds for each plant was obtained according to Jeong et al. (2012) to calculate SPP by measuring the number of 1-seed pods, 2-seed pods, 3-seed pods and 4-seed pods of five plants in Akita and three plants in Kyoto in each plot. After threshing with a thresher, seeds were air-dried and weighed. SW was determined by dividing weight of seed mass by the number of plants harvested in each plot. HSW was measured twice by weighting 100 healthy seeds randomly selected from air-dried seeds. Moisture content was determined with a grain moisture tester (PM830-2; Kett Electric Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan), and SW and HSW were calibrated by adjusting seed moisture content to 15%. PRO and OL were determined by a near-infrared spectrophotometer (Infratec 1241 Grain Analyzer; FOSS Hillerød, Denmark). NSP was calculated by multiplying NPP by SPP.

Statistical analyses were conducted by the statistical package R ver 2.12.2 (http://www.r-project.org/). The statistical significance of differences was evaluated by Student’s t-test for comparisons between two groups. Correlations between traits were examined by Pearson product-moment correlation analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of Dt1 alleles between the parents of RILs and Dt1 genotyping of RILs

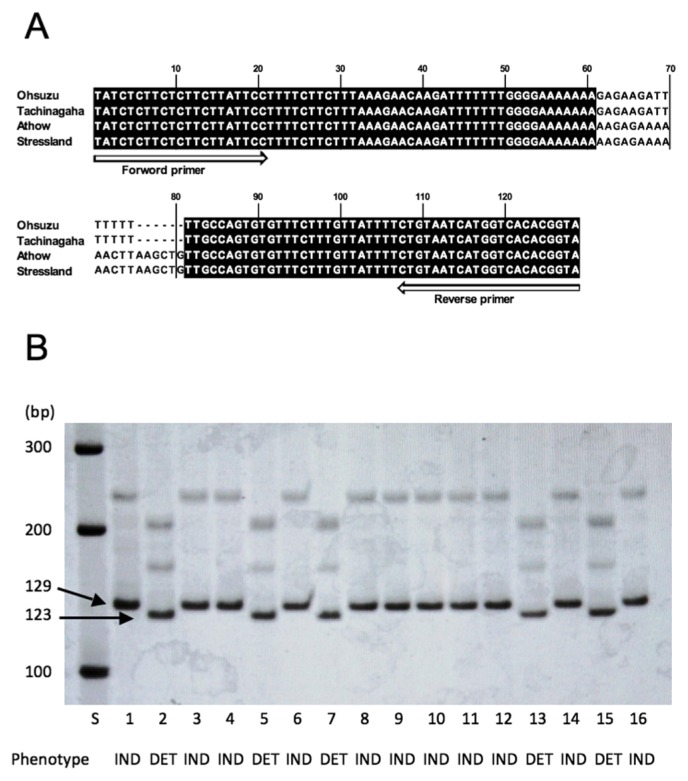

The evaluation of stem termination is sometimes difficult depending on cultivation condition (i.e., lodging and shading by neighboring lines). For judging stem termination precisely, we developed a DNA marker of GmTFL1 for predicting stem termination beforehand and confirmed it by visual inspection. Because some alleles in the GmTFL1 locus, i.e., GmTFL1-a (Dt1), GmTFL1-b (Dt1), Gmtfl1-ta (dt1), Gmtfl1-ab (dt1), Gmtfl1-bb (dt1) and Gmtfl1-tb (dt1), have been reported previously, we identified the alleles of GmTFL1 of the parents of RILs by sequencing the GmTFL1 locus from −740 to +1440 (nucleotide positions from the start codon) (Tian et al. 2010). There were four sequence polymorphisms between the DET cultivars, i.e., ‘Ohsuzu’, ‘Tachingaha’, and the IND cultivars, i.e., ‘Athow’ and ‘Stressland’. These cultivars were classified into two groups according to the sequence polymorphism of GmTFL1. The GmTFL1 sequences of ‘Athow’ and ‘Stressland’ were completely the same as the sequence of GmTFL1-a (Dt1) (Tian et al. 2010). ‘Ohsuzu’ and ‘Tachinagaha’ had AAAAA[T]TTCTT in 5′ UTR (−499), TATGA[G]CAGCG in 5′ UTR (−410), AAA[GAGAAGATTTTTTT]TTG in the 1st intron (+279–+292) and CACAG[T]GGGAA in the 4th exon (+1283), which were completely the same as the sequence of GmTFL1-ab (dt1) (Tian et al. 2010). In the 1st intron (+279–+292), a length polymorphism of 6 bp was identified (Fig. 1A), as shown in a previous study (Tian et al. 2010). The GmTFL1 genotypes of the parents and the lines in OA-RILs and ST-RILs were analyzed by distinguishing the 6-bp length polymorphism in the 1st intron within PCR products amplified by a primer pair of Dt1Int (Fig. 1B). The PCR products of ‘Ohsuzu’ and ‘Tachinagaha’ (dt1 genotype) produced bands of 123 bp, while the PCR products of ‘Athow’ and ‘Stressland’ (Dt1 genotype) produced bands of 129 bp (Fig. 1B). All the lines showing 129-bp bands were IND as ‘Athow’ and ‘Stressland’, whereas all the lines showing 123-bp bands were DET as ‘Ohsuzu’ and ‘Tachinagaha’ (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Association of stem growth habit with DNA polymorphism of Dt1. A. Alignment of nucleotide sequences of PCR products amplified by a pair of primer Dt1Int showing 6-bp length polymorphism between cultivars with Dt1 (Ohsuzu and Tachinagaha) and dt1 (Athow and Stressland). B. PCR products amplified by a pair of primer Dt1Int (separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel). Stem termination was evaluated by visual inspection of main stem growth after flowering. Analyzed plants are as follows: 1, ‘Stressland’; 2, ‘Tachinagaha’; 3–16, recombinant inbred lines derived from the cross between ‘Stressland’ and ‘Tachinagaha’. S indicates 100-bp DNA ladder (Promega G2101). IND: indeterminate growth plant, DET: determinate growth plant.

Genotyping of each line analyzed by the 6-bp length polymorphism classified 225 OA-RILs into 137 IND lines, 87 DET lines and 1 hetero line, in which the genotype was segregated, and classified 118 ST-RILs into 66 IND lines and 52 DET lines. This result completely matched results of the visual inspection of main stem growth and termination. The hetero line and some lines exhibiting physiological disorders or diseases were excluded. As a result, in OA-RILs, evaluated lines were 136 IND and 80 DET in 2009 in Akita, 130 IND and 78 DET in 2010 in Akita, and 26 IND and 26 DET in 2010 at Kyoto. In ST-RILs, 48 IND and 42 DET were examined in 2010 in Akita and 32 IND and 28 DET were tested in 2010 in Kyoto.

Comparison of flowering time, maturation time, protein content, oil content and SW between IND and DET

Mean values of FT, MT, SW, OIL and PRO in IND and DET of OA-RILs and ST-RILs in Akita and Kyoto are given in Table 1. A significant difference of flowering time between IND and DET was observed in OA-RIL. IND flowered 2 days earlier in Akita and 3 days earlier in Kyoto than DET in OA-RILs. As for maturation time, no significant differences were detected. Differences of protein and oil contents between IND and DET were also small and not significant, except for ST-RILs in Kyoto. The average protein content of five experiments was 41.9% in IND and 42.2% in DET, whereas oil content was 20.9% in IND and 20.8% in DET. On the other hand, the difference of SW between IND and DET was evident. In Akita, SW of IND was heavier than that of DET, and the differences were significant in both OA-RILs and ST-RILs. By contrast, in Kyoto, SW of DET was significantly heavier than that of IND in OA-RILs and there was no significant difference between IND and DET in ST-RILs.

Table 1.

Flowering and maturation time, seed weight and ingredient contents of DET and IND of RILs

| RILs | Location | Year | Growth habit | No. of lines | FT (day) | MT (day) | SW (g) | PRO (%) | OIL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA-RILs | Akita | 2009 | P1: Ohsuzu | 1 | 46 | 106 | 28.6 | 42.6 | 20.3 |

| P2: Athow | 1 | 41 | 114 | 27.6 | 40.6 | 21.5 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| IND | 136 | 47 | 117 | 27.2 | 42.5 | 20.0 | |||

| DET | 80 | 49 | 116 | 25.7 | 42.3 | 19.8 | |||

| ** | ns | * | ns | ns | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

| 2010 | P1: Ohsuzu | 1 | 39 | 113 | 27.9 | 42.5 | 21.3 | ||

| P2: Athow | 1 | 35 | 114 | 22.8 | 40.2 | 22.6 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| IND | 130 | 40 | 119 | 25.1 | 40.7 | 21.7 | |||

| DET | 78 | 42 | 120 | 23.0 | 40.6 | 21.8 | |||

| ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Kyoto | 2010 | P1: Ohsuzu | 1 | 32 | 106 | 51.2 | 44.6 | 20.2 | |

| P2: Athow | 1 | 29 | 107 | 55.3 | 40.4 | 22.5 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| IND | 26 | 32 | 114 | 48.5 | 43.7 | 21.1 | |||

| DET | 26 | 35 | 116 | 53.7 | 43.3 | 20.9 | |||

| * | ns | * | ns | ns | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ST-RILs | Akita | 2010 | P1: Stressland | 1 | 43 | 128 | 64.3 | 40.3 | 22.0 |

| P2: Tachinagaha | 1 | 50 | 140 | 52.8 | 42.0 | 20.6 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| IND | 48 | 47 | 134 | 51.5 | 42.0 | 21.0 | |||

| DET | 42 | 48 | 134 | 44.3 | 42.4 | 21.0 | |||

| ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Kyoto | 2010 | P1: Stressland | 1 | 33 | 118 | 45.0 | 42.2 | 21.5 | |

| P2: Tachinagaha | 1 | 34 | 124 | 52.5 | 44.2 | 21.0 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| IND | 32 | 34 | 125 | 45.9 | 43.6 | 21.2 | |||

| DET | 28 | 33 | 121 | 45.8 | 45.1 | 20.6 | |||

| ns | ns | ns | ** | ** | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Overall | IND | 372 | 43 | 120 | 32.7 | 41.9 | 20.9 | ||

| DET | 254 | 43 | 121 | 33.0 | 42.2 | 20.8 | |||

| ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |||||

DET: determinate growth plants, IND: indeterminate growth plants, FT: flowering time, MT: maturation time, SW: seed weight per plant, PRO: protein content, OIL: oil content.

significant between IND and DET at 5.0%, 1.0% and 0.1% levels, respectively (Student’s t-test).

Comparison of relationship between SW and MT of IND and DET

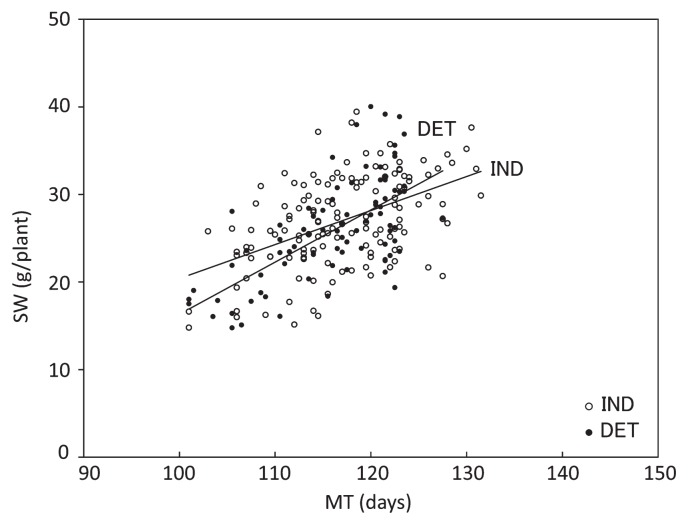

The relationship between SW and MT in OA-RILs grown in Akita in 2009 is shown in Fig. 2 to determine the differences of this relationship between IND and DET. A regression line of SW at maturation time is shown for each growth habit. There was a positive correlation between MT and SW and its correlation coefficient was significant at 0.1% (Fig. 2). As shown by two regression lines, SW was much heavier in IND at the early MT and the difference was large. However, when MT was later, the difference became smaller.

Fig. 2.

Relationship of seed weight per plant (SW) with maturation time (MT) in OA-RILs in Akita in 2009. Regression of SW to MT was analyzed in each group of indeterminate (IND) and determinate (DET) lines. Regression analysis y = bx + a, IND R2: 0.25***, b = 0.38 ± 0.06; DET R2: 0.42***, b = 0.57 ± 0.08

Comparison of yield components between IND and DET

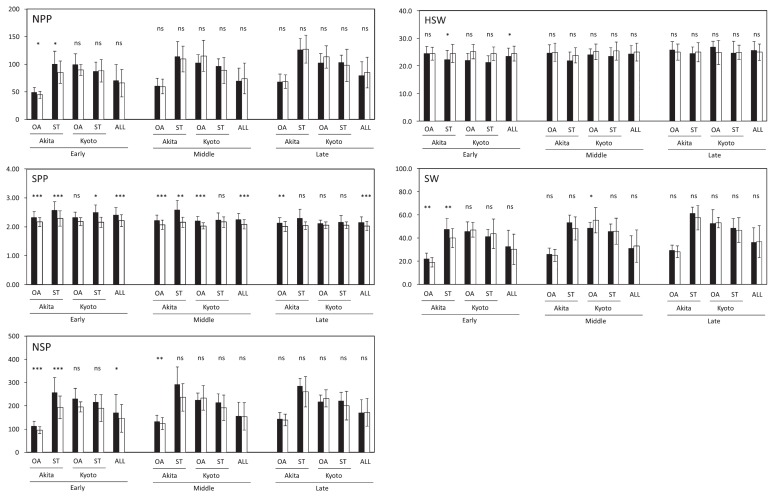

Since the difference of SW between IND and DET varied depending on MT, RILs were classified into three groups, i.e., early, middle and late MT, in each year and each location by dividing the difference of days between the earliest and the latest MT lines into three equal parts. SW and its components were compared between IND and DET within each MT group (Fig. 3). Throughout the five experiments, there were no significant differences in SW and NPP between IND and DET in early, middle and late MT. By contrast, SPP of IND was significantly more than that of DET in early, middle and late MT. NSP of IND was more than that of DET only in early MT, whereas HSW of DET was more than that of IND only in early MT.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of SW and its yield components between indeterminate (IND) and determinate (DET) lines with early, middle and late MT in OA-RILs and ST-RILs. *, **, ***: significant at 5.0%, 1.0% and 0.1% levels, respectively (Student’s t-test). RILs were classified into three groups, i.e., early, middle and late MT, in each location by dividing the difference of days between the earliest and latest MT lines into three equal parts. Black and white bars indicate IND and DET, respectively. NPP: number of pods per plant, SPP: number of seeds per pod, NSP: number of seeds per plant, HSW: 100-seed weight, SW: seed weight per plant. The data of OA-RILs in Akita include the data of OA-RILs in Akita in 2009 and 2010.

Large SW of the early maturing IND was found to be statistically significant in Akita in both OA-RILs and ST-RILs (Fig. 3). SW of IND was significantly less than that of DET in OA-RILs in Kyoto in the middle MT. HSW of DET was a little heavier than that of IND although the difference of HSW between IND and DET was not significant except for that of ST-RILs in Akita in the early MT. NPP and NSP of IND were significantly more than those of DET in Akita in the early MT of OA-RILs and ST-RILs. This confirms that IND exhibit high yield when both NPP and SPP are large.

Discussion

This study was conducted to evaluate the benefits of introduction of the IND trait, which is predominant in the northern US varieties, into DET Japanese varieties for improving their yield potential. Two RIL populations derived from crosses between Japanese DET and U.S. IND cultivars were grown in Akita and Kyoto, and seed weight per plant and its components, i.e., number of pods per plant, number of seeds per pod and 100-seed weight, were measured and compared between IND and DET. This comparison indicated that the influence of growth habit on seed weight per plant varies with MT and that the high yield due to IND is prominent in the early MT of a short growing period. Similar results showing that the influence of growth habit on the seed yield is inconsistent depending on MT have been reported (Bernard 1972, Cober and Morrison 2010, Wilcox and Frankenberger 1987). Our result suggests that introduction of IND into the breeding program would be advantageous for improving yield potential of early maturing varieties in the Tohoku region.

The relation between growth habit and yield may vary depending on environments and genetic backgrounds. In the present study, two RIL populations were used for evaluation of the effect of the genetic background. In the two RIL populations, i.e., OA-RILs and ST-RILs, Japanese parents were ‘Ohsuzu’ and ‘Tachinagaha’, respectively, having large seed size. MT of ‘Ohsuzu’ is early (MG_III) and that of ‘Tachinagaha’ is late (MG_V), meaning that they cover a broad range of MT of domestic soybean varieties. In addition, for evaluating the difference between IND and DET with various genetic combinations, we used the RIL populations from the crosses between Japanese and U.S. cultivars. Therefore, our results on the effect of growth habit on seed yield would be broadly applicable to the domestic breeding program of soybean.

Furthermore, the RILs were grown in two locations, i.e., Akita and Kyoto, to evaluate the effect of environmental conditions on the seed yields of IND and DET. IND showed significantly heavier seed weight per plant in early MT in Akita, whereas in Kyoto, DET showed significantly heavier seed weight per plant in middle MT in OA-RILs and there was no significant difference between IND and DET in ST-RILs (Table 1). These results suggest that the introduction of IND into the breeding program would be more successful for the Tohoku region, where ensuring sufficient growth is difficult in early maturing varieties with short growing periods.

The number of seeds per plant of IND with early MT was significantly more than that of DET of OA-RILs and ST-RILs in Akita. By contrast, 100-seed weight of IND with the early MT was significantly lighter than that of DET of ST-RILs, but there was no significant difference between IND and DET of OA-RILs in Akita. These findings indicate that the high seed weight per plant of IND with the early MT in Akita was due to the high number of seeds per plant values. When the number of seeds per plant was further divided into number of pods per plant and number of seeds per pod, the number of seeds per pod of IND in Akita was significantly more than that of DET for all MTs except for ST-RILs in the late MT, while the number of pods per plant of IND was significantly more than that of DET only in the early MT. This indicates that the number of seeds pod was large for all MTs in IND. In addition, IND exhibited large number of pods per plant in the early MT. The high seed yield of IND was substantiated by the fact that the small seed size was compensated for by the large number of seeds.

In IND, nodes on the main stem continue to differentiate after onset of flowering, resulting in an increase of nodes. The number of nodes on the main stem steadily increases according to maturation time in both IND and DET. The difference in the number of nodes between IND and DET is relatively large in the early MT, where the number of nodes of DET plants is likely to be considerably small (Bernard 1972, Curtis et al. 2000, Hartung et al. 1981). The large number of pods per plant of IND with the early MT in the present study may have been caused by the large number of nodes on the main stem. On the other hand, the number of seeds per pod was constantly large irrespective of MT. A genetic factor controlling leaf shape has been reported to be responsible for the number of seeds per pod, which was found to be large in a narrow leaf genotype (Dinkins et al. 2002). Recently a gene controlling leaf shape has been identified (Gm-JAG1), and it has been revealed that it affects the number of seeds per pod as a pleiotropic effect (Jeong et al. 2012). As the parents of ST-RILs, ‘Stressland’ has broad leaflets and ‘Tachinagaha’ has narrow ones, whereas the two parents of OA-RILs have similar broad leaflets. Since segregation of the stem growth habit in RILs is independent of the leaf shape (Jeong et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2010), a gene controlling leaf shape is not considered to be responsible for the large number of seeds per pod in IND. Effects of IND on the number of seeds per pod have been reported by Hicks et al. (1969). They used near isogenic lines (NILs) of ‘Harosoy’ and ‘Clark’ (Dt1/dt1) and concluded that the number of three-seed pods in IND is significantly greater than those in DET, whereas two-seed pods in IND are significantly fewer than those in DET. It is necessary to verify the effect of the introduction of the IND trait on the number of seeds per pod in detail by using mutants or transgenic plants.

Since about half the amount of domestic soybean production is used for tofu processing, the balance between PRO and OIL influencing tofu processability, i.e., tofu yield and tofu texture, is important (Huang et al. 2014, Poysa and Woodrow 2002). In PRO and OIL, although there was little difference between IND and DET throughout the five experiments, the effects of the introduction of the IND trait on PRO and OIL were different depending on MT, cultivation environment and genetic background, consistent with previous reports (Bernard 1972, Cober and Morrison 2010, Ouattara and Weaver 1994, Wilcox and Zhang 1997). Therefore, the effect of the introduction of the IND trait on PRO and OIL should be evaluated in each cultivation environment and genetic background.

In the cultivation of soybean, lodging is a serious problem for machinery harvest. IND can be considered to be susceptible to lodging because of its tall plant height due to elongation of the main stem after flowering. In IND, as nodes are higher, leaves become smaller, resulting in a corn-like plant shape (Thseng and Hosokawa 1972). Weight of the upper part of a plant is likely to be lighter than that of the lower part. In early MT lines, plant height tends to be low. Therefore, the IND trait combined with the early MT may not necessarily result in severe lodging (Cober 2010). MT is also important for identification of regions where a new cultivar can be distributed. There was little difference in MT between IND and DET (Table 1). Consequently, no disadvantage is inferred in the breeding for high yielding varieties having the IND trait and the early MT.

The 100-seed weight of IND with the early MT was slightly smaller than that of DET (Fig. 2). If the seed size of IND with the early MT can be increased, its high yield potential will be further advanced. Since several QTLs of seed size have been found (Kato et al. 2014), DNA markers of these QTLs will enable backcross breeding of large-seed lines using a high yielding IND line as a recurrent parent.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan [Genomics for Agricultural Innovation (SOY2002 and SOY2004)].

Literature Cited

- Bernard, R.L. (1972) Two genes affecting stem termination in soybeans. Crop Sci. 12: 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma, H.R. and Ashley, D.A. (1982) Irrigation, row spacing, and genotype effects on late and ultra-late planted soybeans. Agron. J. 74: 995–999. [Google Scholar]

- Cober, E.R. and Tanner, J.W. (1995) Performance of related indeterminate and tall determinate soybean lines in short-season areas. Crop Sci. 35: 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Cober, E.R. and Morrison, M.J. (2010) Regulation of seed yield and agronomic characters by photoperiod sensitivity and growth habit genes in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120: 1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.L. and Waranyuwat, A. (1985) Effect of three genes (Pd, Rps1a, and ln) on plant height, lodging, and seed yield in indeterminate and determinate near-isogenic lines of soybeans. Crop Sci. 25: 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.L., Martin, R.J., St Martin, S.K., Calip-DuBois, A., Fioritto, R.J. and Schmitthenner, A.F. (1999) Registration of ‘Stressland’ soybean. Crop Sci. 39: 590–591. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, D.F., Tanner, J.W., Luzzi, B.M. and Hume, D.J. (2000) Agronomic and phenological differences of soybean isolines differing in maturity and growth habit. Crop Sci. 40: 1624–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkins, R.D., Keim, K.R., Farno, L. and Edwards, L.H. (2002) Expression of the narrow leaflet gene for yield and agronomic traits in soybean. J. Hered. 93: 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley, T.C., Orf, J.H. and Lambert, J.W. (1986) Performance of related determinate and indeterminate soybean lines. Crop Sci. 26: 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, R.C., Specht, J.E. and Williams, J.H. (1981) Modification of soybean plant architecture by genes for stem growth habit and maturity. Crop Sci. 21: 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, D.R., Pendleto, J.W., Bernard, R.L. and Johnston, T.J. (1969) Response of soybean plant types to planting patterns. Agron. J. 61: 290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M., Kaletunc, G., Martin, S.S., Feller, M. and McHale, L.K. (2014) Correlations of seed traits with tofu texture in 48 soybean cultivars and breeding lines. Plant Breed. 133: 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, N., Suh, S.J., Kim, M.H., Lee, S., Moon, J.K., Kim, H.S. and Jeong, S.C. (2012) Ln is a key regulator of leaflet shape and number of seeds per pod in soybean. Plant Cell 24: 4807–4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, S., Sayama, T., Fujii, K., Yumoto, S., Kono, Y., Hwang, T.Y., Kikuchi, A., Takada, Y., Tanaka, Y., Shiraiwa, T.et al. (2014) A major and stable QTL associated with seed weight in soybean across multiple environments and genetic backgrounds. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127: 1365–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.H., Watanabe, S., Uchiyama, T., Kong, F.J., Kanazawa, A., Xia, Z.J., Nagamatsu, A., Arai, M., Yamada, T., Kitamura, K.et al. (2010) The soybean stem growth habit gene Dt1 is an ortholog of Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER1. Plant Physiol. 153: 198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBroom, R.L., Hadley, H.H., Brown, C.M. and Johnson, R.R. (1981) Evaluation of soybean cultivars in monoculture and relay intercropping systems. Crop Sci. 21: 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, S., Shigemori, I., Takahashi, N., Tezuka, M., Yagasaki, K., Kobayashi, T. and Mikoshiba, K. (1987) A new soybean variety “Tachinagaha”. Bull. Nagano Chushin. Agric. Exp. Stn. 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, T. (1967) Studies on the significance of indeterminate growth habit in breeding soybeans. 3. Varietal difference in fruting process attributable to the habit. a. Maturity and growth habit of pods and seeds. Jpn. J. Breed. 17: 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ouattara, S. and Weaver, D.B. (1994) Effect of growth habit on yield and agronomic characteristics of late-planted soybean. Crop Sci. 34: 870–873. [Google Scholar]

- Ouattara, S. and Weaver, D.B. (1995) Effect of growth habit on yield components of late-planted soybean. Crop Sci. 35: 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, A.Q., Gardner, F.P. and Boote, K.J. (1989) Determinate- and indeterminate-type soybean cultivar responses to pattern, density, and planting date. Crop Sci. 29: 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, T.W. and Harris, L.C. (1990) Soybean yield in delayed plantings as affected by alleles increasing vegetative weight. Field Crops Res. 23: 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Poysa, V. and Woodrow, L. (2002) Stability of soybean seed composition and its effect on soymilk and tofu yield and quality. Food Res. Int. 35: 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.L. and Wilcox, J.R. (1998) Comparison of determinate and indeterminate soybean near-isolines and their response to row spacing and planting date. Crop Sci. 38: 1554–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, J.G., Wilcox, J.R. and Probst, A.H. (1971) Response of soybean genotypes to spacing in hill plots. Crop Sci. 11: 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, S., Shiraiwa, T., Katsura, K. and Shimamura, S. (2013) The difference of soybean production between Japan and U.S.A. and problems of Japanese soybean production. In: Umemoto, M. and Shimada, S. (eds.) Subject and prospect for Japanese soybean production. Agricultural Research Series of the NARO Agricultural Research Center 68, pp. 69–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi, K., Adachi, T., Shimada, H., Kikuchi, A., Takahashi, K., Takada, Y., Nakamura, S., Yumoto, S., Kowata, M., Banba, H.et al. (1999) A new soybean variety “Ohsuzu”. Bull. Tohoku Natl. Agric. Exp. Stn. 95: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Thseng, F.S. and Hosokawa, S. (1972) Significance of growth habit in soybean breeding: I. Varietal differences in characteristics of growth habit. Jpn. J. Breed. 22: 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.X., Wang, X.B., Lee, R., Li, Y.H., Specht, J.E., Nelson, R.L., McClean, P.E., Qiu, L.J. and Ma, J.X. (2010) Artificial selection for determinate growth habit in soybean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 8563–8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D.B., Akridge, R.L. and Thomas, C.A. (1991) Growth habit, planting date, and row-spacing effects on late-planted soybean. Crop Sci. 31: 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, J.R. and Frankenberger, E.M. (1987) Indeterminate and determinate soybean responses to planting date. Agron. J. 79: 1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, J.R. and Abney, T.S. (1997) Registration of “Athow’ soybean. Crop Sci. 37: 1981–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, J.R. and Zhang, G.D. (1997) Relationships between seed yield and seed protein in determinate and indeterminate soybean populations. Crop Sci. 37: 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, T., Hajika, M., Yamada, N., Hirata, K., Okabe, A., Oki, N., Takahashi, K., Seki, K., Okano, K., Fujita, Y.et al. (2012) Effect on flowering and seed yield of dominant alleles at maturity loci E2 and E3 in a Japanese cultivar, Enrei. Breed. Sci. 61: 653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]