Highlights

-

•

Cell-free expression of functional bacterial Na channel in mg quantities achieved.

-

•

The described method can be adopted for efficient site-directed isotope labelling.

-

•

This high throughput production enables bio-spectroscopic investigations.

Keywords: Cell-free expression, Membrane protein, Sodium channel

Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channels participate in the propagation of action potentials in excitable cells. Eukaryotic Navs are pseudo homotetrameric polypeptides, comprising four repeats of six transmembrane segments (S1–S6). The first four segments form the voltage-sensing domain and S5 and S6 create the pore domain with the selectivity filter. Prokaryotic Navs resemble these characteristics, but are truly tetrameric. They can typically be efficiently synthesized in bacteria, but production in vitro with cell-free synthesis has not been demonstrated. Here we report the cell-free expression and purification of a prokaryotic tetrameric pore-only sodium channel. We produced milligram quantities of the functional channel protein as characterized by size-exclusion chromatography, infrared spectroscopy and electrophysiological recordings. Cell-free expression enables advanced site-directed labelling, post-translational modifications, and special solubilization schemes. This enables next-generation biophysical experiments to study the principle of sodium ion selectivity and transport in sodium channels.

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels (Navs)2 are membrane proteins from the superfamily of voltage-gated ion channels, closely related to voltage-gated potassium channels and voltage-gated calcium channels [1]. Navs are present in all excitable cells, where they participate in the propagation of action potentials by changing the Na+ permeability of the cell membrane. Most voltage-gated ion channels comprise of similar building blocks and are mainly alpha-helical. Navs comprise six transmembrane segments (S1–S6), where S1–S4 form the voltage-sensing domain and S5 and S6 create the pore domain. In bacteria, four of these subunits arrange around a central pore to form a functional channel. In higher organisms, all four subunits are assembled from a single polypeptide chain, which may associate with auxiliary subunits [2].

Eukaryotic sodium channels were discovered first and have been the subject to extensive research for many decades [3]. However, the discovery of a prokaryotic bacterial sodium channel in 2001 [4] was a prerequisite for solving the proteins’ three dimensional crystal structure [5], mainly because it enabled production of larger amounts of channel protein. Bacterial Navs have 20–25% identity with human Navs and are expected to have a similar fold as they have nearly identical hydrophobicity profiles and predicted topologies in each of the pseudo-repeated eukaryotic domains [6]. Despite the available structural information, the mechanisms of molecular ion transport and ion selectivity are still not completely understood. X-ray crystallography catches high-resolution structures of stationary states, but lacks dynamic information. In principle, molecular dynamics simulations can be used to produce dynamical models. However, for potassium channels [7], such simulations have led to radically different proposals for mechanisms for ion transport [8,9]. This emphasizes the need for experimental validation. As we point out below, suitable experiments are today becoming possible. They may require sophisticated and site-selective modifications of the protein, which is asking for efficient production of Navs with cell-free (in vitro) synthesis.

In cell-free expression, proteins are expressed from exogenous template DNA added to the transcription and translation enzymes extracted from a cell lysate. This in vitro synthesis is becoming increasingly popular, particularly because it is possible to produce proteins which aggregate, or proteins which are toxic to host cells [10–14]. Today, typical yields of 0.3 mg to several milligrams of protein per mL reaction mixture can be achieved in batch or in continuous mode, respectively, and popular reaction mixtures are extracted from Escherichia coli or wheat germs [14–16]. As cell-free expression gives direct access to the nascent polypeptide, it facilitates co-translational solubilization of membrane proteins in a wide range of detergents, lipids and nanodiscs [10,17]. Indeed, functional membrane proteins [10–13] including ion channels such as connexins [18], nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [19], drosophila olfactory receptors [20] and potassium channels can be produced by in vitro synthesis [17,21,22]. Also, eukaryotic sodium channels protein were synthesized in vitro [23]. Most of these examples were produced in cell extracts that yield microgram quantities of proteins, which is sufficient for electrophysiological studies, but not for spectroscopic and crystallographic investigations [18,19,21–23]. Isotope-labelled proteins are easily available as the amino acids are added to the reaction mixture as required [24].

In-vitro synthesis of ion channels is useful, because it may pave the way for the investigation of the molecular details of ion conductance in channel proteins. It has been demonstrated that in vitro synthesis enables time-saving direct reconstitution into oocytes [17]. Room temperature spectroscopy methods, such as NMR and vibrational spectroscopy, can in principle be used to study ion channels in native environments. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy is particularly interesting, because it can be used to characterize biological processes involving protein conformational change, e.g. transport or charge transfer with picosecond time resolution [25,26]. A specific infrared experiment to study the occupancy in selectivity filters of ion channels has been suggested [27]. Nonetheless, it is usually problematic to assign vibrational spectral signatures to specific sites in proteins, except for when these sites are labelled with isotopes or specific chemical groups [27–29]. In-vitro synthesis of protein makes possible site-directed labelling with specific amino acids using amber-stop codon technology [30,31]. To realize this new generation of spectroscopic experiments, reliable in vitro production of milligram quantities of ion channels is a prerequisite.

Here we report the production of a bacterial pore-only sodium channel from Silicibacter pomeroyi (NavSp1p) [32]. Designed and explored by the Minor group, the pore domain folds independently of the voltage-sensing domain into a functional channel protein, which displays selectivity for sodium over potassium ions. When produced in E. coli, it is more stable and expresses at higher levels than the complete channel [32]. We show here that cell-free production of a few milligrams of NavSp1p is possible, that the protein is folded correctly, and that a functional sodium channel is produced.

Material and methods

Extract cultivation, preparation

S12 extract was prepared from BL21 (DE3):RFI-CBD3 [31] as described in [33]. Briefly, cells were grown in a 20 L fermentor (Braun Biostat C) at 37 °C in 2xYPTG medium supplemented with choline chloride (Fluka 28.6 mg/L), nicotinic acid (Acros, 25.1 mg/L), p-aminobenzoic acid (Aldrich, 20.0 mg/L), pantothenic acid calcium salt (Fluka, 9.4 mg/L), pyridoxal-5-phosphate (1.8 mg/L), (−)-riboflavin (3.9 mg/L), thiamine hydrochloride (USB Corporation, 17.7 mg/L), betaine hydrochloride (Calbiochem, 33.1 mg/L), D-biotin (MP Biomedicals, 0.1 mg/L), cyanocobalamin (Fluka, 0.01 mg/L), folinic acid calcium salt hydrate (Sigma, 0.075 mg/L), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (Scharlau Chemie S.A., 20.0 mg/L), sodium molybdate dehydrate (Acros, 3.5 mg/L), boric acid (1.2 mg/L), cobalt sulphate heptahydrate (4 mg/L), copper sulphate pentahydrate (Merck KGaA, 3.4 mg/L), manganese sulphate hydrate (Merck KGaA, 1.9 mg/L), zinc sulphate heptahydrate (Scharlau Chemie S.A., 3.4 mg/L), and amino acids (Asp (28.5 mg/L), Gly (49.1 mg/L), His (9.35 mg/L), Ile (26.2 mg/L), Leu (29.9 mg/L), Lys (31.4 mg/L), Met (14.9 mg/L), Phe (15.3 mg/L), Pro (31.8 mg/L), Thr (37.7 mg/L), Trp (102.1 mg/L), Tyr (37.7 mg/L), Val (117.1 mg/L)). At OD600 ∼4.5 temperature was decreased to 10 °C by passing the cell suspension through a metal coil immersed in ice water, cells were harvested, washed with extraction buffer (10 mM Tris–acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM Mg(OAc)2, 60 mM K(OAc), cOmplete EDTA-free (Roche)), and finally resuspended in 10 mL extraction buffer/8 g of wet cells. The cells were lysed by a French press (two passages, 24,000 psi, ThermoFisher), centrifuged at 12,100g (10 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was decanted into fresh tubes and incubated for 2 h at a shaking incubator (30 °C, 150 rpm). We removed the release factor 1 protein from the cell extract. This is important for potential subsequent site-directed labelling steps with amber stop codons [30,34]. The S12 extract was passed over chitin resin (New England Biolabs) directly after the incubation and removal was confirmed by Western blotting. After addition of 1 mM DTT the S12 extract was dialyzed twice against extraction buffer supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol (1 mL/L), flash frozen, and stored at−80 °C.

Cell-free protein expression was performed in batch mode as described by [33]. Briefly, plasmid 0.01 μg/μL DNA, 14–20 mM Mg(OAc)2, all 20 amino acids (1 mM each, besides Gln (4 mM) and Ser (2 mM)), 27.4 mM NH4OH, 212 mMd-Glu, 230 mM KOH, 52.5 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.0), 1.1 mM ATP, 800 μM GTP, 800 μM CTP, 800 μM UTP, 640 μM cAMP, 68 μM folinic acid (BioXtra), 1.7 mM DTT, 51.6 mM creatine phosphate (Roche), 4.4 mMl-(−)-malic acid (Fluka), 1.5 mM succinate (SAFC), 1.9 mM α-ketoglutaric acid (Fluka), 175 μg/mL tRNA (Roche), 8 U/mL RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (Thermofischer), 1xcOmplete EDTA-free (Roche), 50 μg/mL T7RNA polymerase (prepared according to [35,36]), 125 μg/mL creatine kinase (Roche), 31% (v/v) S12, and detergents were mixed. Brij®-58 (polyoxyethylene (20) cetyl ether) and Brij®-78 (polyoxyethylene (18) octadecyl ether) (Sigma) were used at a final concentration of 10 times excess of the critical micelle concentration (CMC), 0.8 mM and 0.46 mM, respectively. DDM (n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside) and DM (n-decyl-β-d-maltoside) (Anagrade Affymetrix) were used at 3 × CMC, 0.6 mM and 5.4 mM, respectively. Mixture was incubated for two hours at 30 °C and 800 rpm. For every batch of S12 the optimal Mg2+ was determined by GFPcyc3 expression. GFPcyc3 fluorescence was measured with a FluoStar plate reader (BMG Labtech, 390 nm (excitation), 520 nm (emission)).

To verify protein expression, Western blotting was performed following the manual for XCell II™ Blot Module and ONE-HOUR Western™ Basic Kit (Mouse) (GenScript) using Anti-His Antibody (GE Healthcare). Chemiluminescence was detected using a Fujifilm Las-1000 Luminescent Image Analyzer Chemi Fuji together with its software.

Overexpression of NavSp1p in E. coli cells

NavSp1p cloned into pHM3C-LIC, a vector containing a N-terminal hexa-His tag, a maltose-binding protein and a HRV 3C cleavage site was a kind gift from Daniel Minor [32]. The construct was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) and expression was performed as described [32].

Purification of NavSp1p from cell-free synthesis and expression in E. coli

We adapted a purification scheme from Shaya et al., 2011. After completed cell-free synthesis, the reaction mixture was centrifuged (16,000g, 20 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was loaded onto a gravity flow Ni–NTA agarose column (Qiagen) equilibrated with buffer A (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 8% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2.7 mM DM). The column was washed with 7 column volumes of buffer A with 20 mM imidazole and eluted by 3 column volumes of buffer A with 300 mM imidazole. Large amounts, as e.g. channel protein produced inE. coli were loaded onto a His-Trap HP column using an Äcta system (GE Healthcare). The sample was desalted using buffer A either by dialysis (MWCO 12–14 kDa) or loaded onto a HiPrep 26/10 Desalting Column (GE Healthcare). The affinity tag and the maltose binding protein were cleaved by a His-labeled in-house HRV 3C protease (see below) at a ratio protein: protease = 1 mg: 0.28 mg at 8 °C overnight with gentle agitation. The protease was removed by a second Ni–NTA column which additionally removes traces of uncleaved protein and the His-tagged maltose binding protein tag. The last purification step was a size exclusion chromatography step (Superdex Increase 200 GL (GE Healthcare), with buffer C (20 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 2.7 mM DM)). Protein purity was evaluated by SDS–PAGE stained with SimpleBlue™ SafeStain (life technologies) and the protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm using NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific), where the extinction coefficient for the uncleaved and cleaved protein was 90,300 M−1 cm−1 and 23,500 M−1 cm−1, respectively.

HRV 3C protease expression and purification

HRV 3C in a pET28 expression vector was obtained from Daniel Minor [32]. 10 mL 2YT (pH 7) containing kanamycin (100 μg/mL) was inoculated with a glycerol stock of pET28 inE. coli BL21 Star and grown overnight (220 rpm, 37 °C). Two liter cultures were inoculated with 6 mL of preculture and grown (180 rpm, 37 °C) to an O.D600 of 0.6–0.8. Then the temperature was reduced to 22 °C and after 15 min, expression was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG (Affymetrix). After 19 h cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000g, 20 min, 4 °C). Pelleted cells were resuspended in 50 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 1 mg lysozyme from chicken egg white, Sigma and 1 mM PMSF) and disrupted using French Press, two passages at 24,000 psi. Cell lysate was separated from unbroken cells and cell debris by ultracentrifugation (42,000g, 1 h, 4 °C). The supernatant containing the octa-histidine tagged 3C protease was loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap™ HP column (GE Healthcare) and equilibrated with chelating buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol). The column was washed with chelating buffer containing 46 mM imidazole and the bound protein was eluted by step application of elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 150 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol). The fractions containing the protein were collected and dialyzed overnight against 2 L dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 5 mM DTT) (MWCO 12–14 kDa, 8 °C). The concentration was measured photometrically using an extinction coefficient of 5960 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm and M.W. was 21.282 kDa. Aliquots were flash frozen and stored at −20 °C.

IR spectroscopy

IR spectrum of the liquid sample was obtained with Agilent Cary 630 FTIR spectrometer with Diamond ATR Accessory. Buffer absorbance was recorded, scaled, and subtracted from sample spectrum as to minimize the water absorbance.

Functional characterization of reconstituted NavSp1p

Purified NavSp1p was incorporated into giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) using procedures described previously [32,37,38]. First, GUVs were produced by electroformation using 10 mM 1,2, diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1 mM cholesterol dissolved in trichloromethane. No phosphatidyl glycerol, phosphatidyl serine nor phosphatidylinositol were added as the lipid sensitivity of pore-only NavSp1p seems to be drastically reduced when compared to full length protein [39]. Approximately 20 μL of lipid solution was placed on the Vesicle Prep Pro (Nanion Technologies) ITO glass surface and air-dried. The dry lipid film was rehydrated using 250 μL 1 M sorbitol. GUVs were formed by electroswelling under the influence of an alternating electrical field for 2 h. GUVs were collected and incubated with protein suspension containing 0.5 μg/mL NavSp1p in 20 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DM for 15 min. Excess detergent was adsorbed by addition of 40 mg mL−1 polystyrene beads (BioBeads SM2 Adsorbant, Biorad Laboratories) to the samples for 4 h. After incubation, BioBeads were separated from the GUVs by centrifugation (1000g, 10 min) and removed. The residual amount of DM after adsorption was not estimated. Empty control vesicles were prepared in a similar manner omitting the protein addition step. Electrophysiology recordings were made immediately following protein reconstitution.

Electrophysiology

All lipid bilayer experiments were performed using a planar patch clamp system (Port-a-Patch, Nanion Technologies GmbH), using borosilicate glass chip with an aperture diameter of approximately 1 μm. Channel activity was recorded in symmetrical condition comprised of 10 mM Na-Hepes, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7 (adjusted with NaOH). To determine the permeability of Na+ and K+, the reversal potential was measured in asymmetric conditions where the internal solution contained 10 mM Na-Hepes, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7 (adjusted with NaOH) and the external solution contained 10 mM Hepes, 110 mM KCl, pH 7 (adjusted with KOH). Data were filtered at 3 kHz (Bessel filter, HEKA amplifier, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) digitized at a sampling rate of 50 kHz and analyzed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments). Bilayer formation process was computer controlled by PatchControl software (Nanion). The permeability ratio was estimated as in Ref. [32,40], according to equation . R, T, F, and Erev are the gas constant, absolute temperature, Faraday constant, and the reversal potential, respectively. Activity coefficients for Na+ and K+ were estimated as follows: , where activity, as, is the effective concentration of an ion in solution, s is related to the nominal concentration [Xs] by the activity coefficient, γs, γs was calculated from the Debye–Hückel equation: where μ is the ionic strength of the solution, zs is the charge on the ion, and αs is the effective diameter of the hydrated ion in nanometers.

Results and discussion

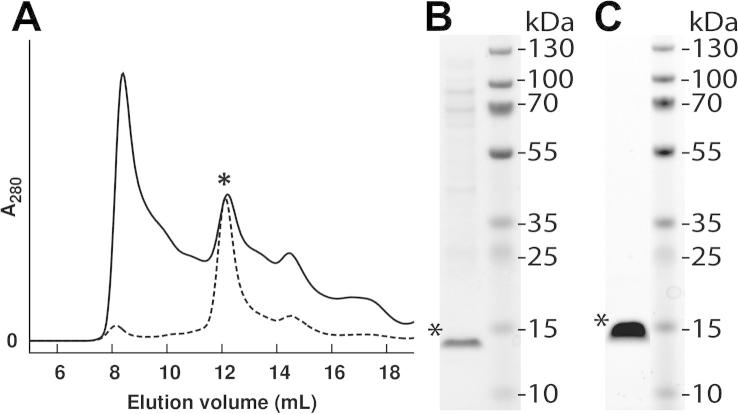

Based on the observation that membrane proteins can be successfully expressed in cell-free systems [10] and that E. coli is a suitable host for expressing the bacterial tetrameric pore-only NavSp1p fused to a maltose-binding protein and a hexa-His tag [32], we tested the expression of NavSp1p in a cell-free system derived from a bacterial extract S12 from E. coli. As NavSp1p is a membrane protein, we first undertook a detergent screen to effectively solubilize NavSp1p in CPFE. Based on literature research [41], we tried four non-polar detergents Brij®-58, Brij®-78, DDM and DM. The expression of NavSp1p was verified by immunoblotting in the crude expression mixture using anti-His antibodies (Fig. 1). We observed an equally strong signal both in the total reaction (T) and in the supernatant (S) indicating that the protein was not only expressed, but also effectively solubilized in all detergents. Next, we optimized the incubation time and temperature. Changing the initial incubation time from 2 h to 4 h and overnight, did not result in a significant change in the yield. A temperature drop from 30 °C to 19 °C inhibited expression in the environment of DM and DDM and but did not change the expression in Brij®-78 and Brij®-58. We chose an incubation temperature and time of 30 °C and 2 h, respectively, and performed expression in DM. The protein was purified using affinity and size exclusion chromatography[32]. Optimization of the amount of protease for cleavage of the maltose binding domain at 8 °C yielded an optimized ratio of 1 mg: 0.28 mg (protein: protease).

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of the solubilization NavSp1p expressed cell-free with four different detergents (Brij®-78, DM, Brij®-58, DDM). The blot is digitally overlaid with a picture of the same nitrocellulose membrane stained with Ponceau S (‘S’ denotes ‘supernatant’, ‘T’ denotes ‘total reaction’). The frame marks the expected size of the fusion protein NavSp1p 62.1 kDa.

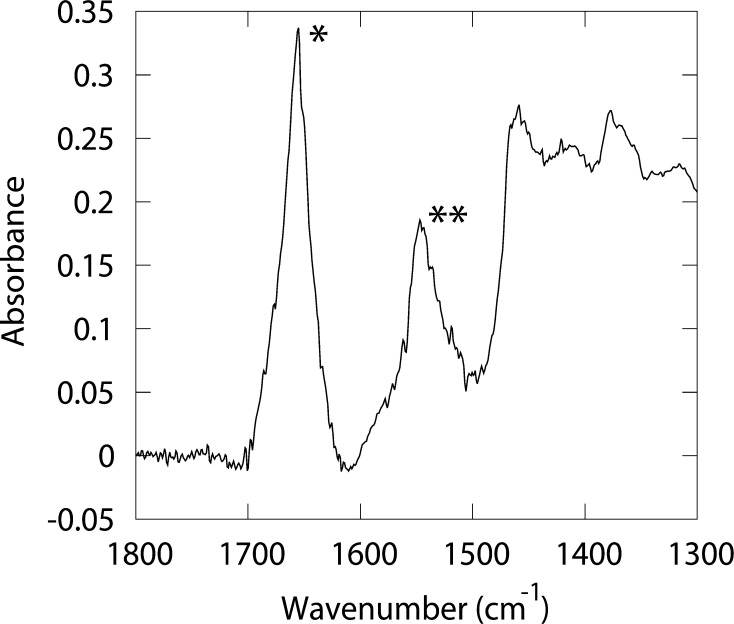

We also expressed NavSp1p in in vivo in E. coli as described [32]. The size-exclusion chromatogram shows that NavSp1p from both expression systems has an identical elution volume (Fig. 2A). This is indicative of elution as a tetramer (67.3 kDa). SDS–PAGE analyses under denaturing conditions (Fig. 2B and C) showed that purification yields a pure protein in both cases and we observed a monomeric NavSp1p with the size of 15.9 kDa. The total yield was 20 μg purified protein per mL of cell-free reaction, which is sufficient for production of milligram amounts. For comparison, the yields of purified cell-free expressed human voltage-dependent anion channel-1 and bacteriorhodopsin were reported as 200–300 μg/ mL and 24 μg/ mL, respectively[11,13], both produced in batch mode format using E. coli extract.

Fig. 2.

Purification of NavSp1p. (A) Size-exclusion chromatogram, full and dashed line mark the absorbance at 280 nm of the NavSp1p obtained from cell-free expression and E. coli cells respectively. Asterisk indicates the collected peak (elution volume of the tetrameric NavSp1p (67.3 kDa) is 11.7–13.2 mL and 11.5–13.5 mL for cell-free expression andE. coli sample, respectively). We note that the large void volume in the sample expressed in vitro is likely due to excess DNA in the reaction mixture. (B, C) SDS-PAGE analyses of collected peaks stained with Coomassie. The asterisk marks the band for monomeric NavSp1p at 15.9 kDa from cell-free expression (B) and from E. coli cells (C).

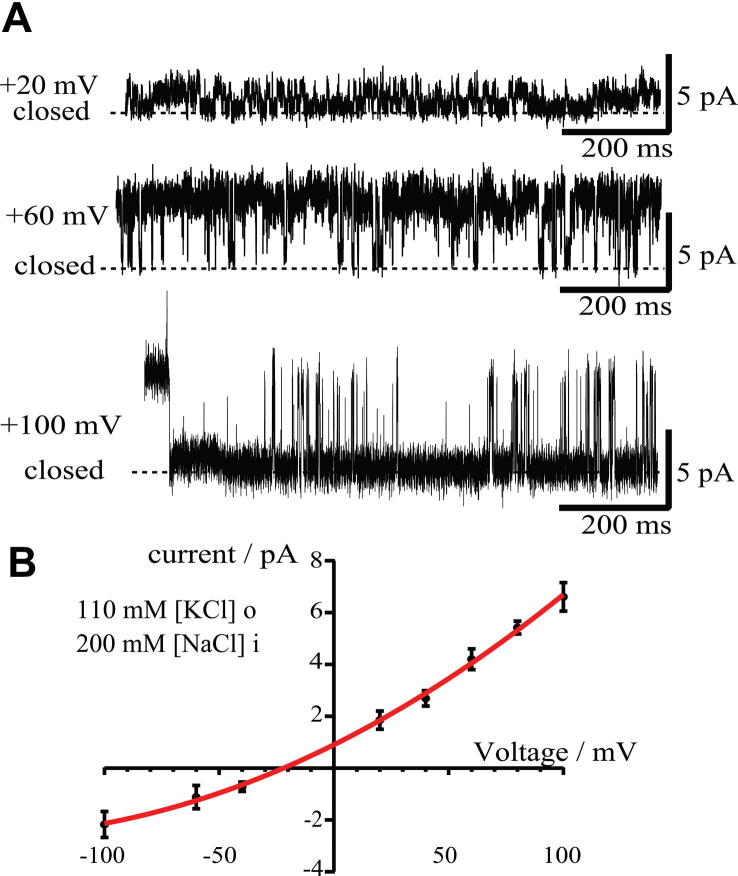

To confirm that the ion channel was folded correctly, we recorded an FTIR spectrum (Fig. 3). The vibrational frequency of the amide I band (1656 cm−1), and the peak shape of the amide I and II bands support the notion that the protein is alpha-helical [42].

Fig. 3.

Corrected FTIR spectra of NavSp1p. The amide I (1600–1700 cm−1) and amide II (∼1550 cm−1) vibrations of the polypeptide backbones are marked with one and two asterisks respectively.

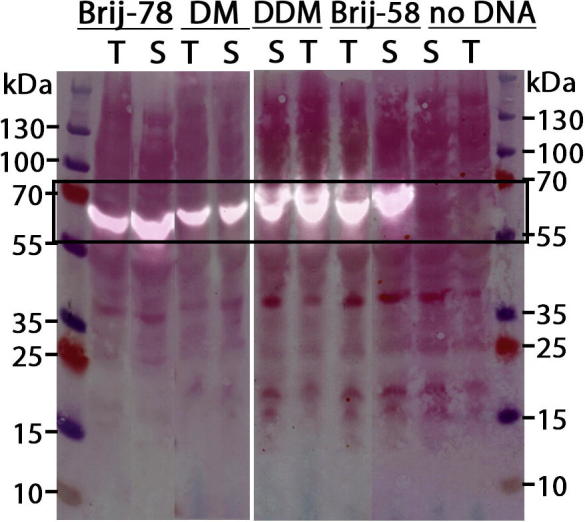

Electrophysiological characterization of the NavSp1p, produced in vitro, reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers was analyzed on the single channel level. The single channel recordings showed that the protein is a functional ion channel with a selectivity for sodium over potassium ions. We measured the conductance levels while varying the holding potential between −100 mV and +100 mV (Fig. 4A). The conductance of NavSp1 was 32.5 ± 2.8 pS under symmetrical condition (200 mM NaCl) which is in a good agreement with the previously reported value for the NavSp1p expressed in E. coli [32]. To further investigate the NavSp1p, we measured its selectivity for sodium over potassium by measuring the reversal potential in a set of asymmetric ion conditions. The current – voltage relationship under asymmetric condition (110 mM KCl extracellular/200 mM NaCl intracellular) showed that NavSp1p has a preference for ions of Na+:K+ = 1:0.27 (Fig. 4B). This indicates that the expressed sodium channel is indeed functional and that it is selective for sodium over potassium ions.

Fig. 4.

Functional characterization of NavSp1p (A) NavSp1p reconstituted in planar lipid bilayer recorded in an asymmetric buffer solution, 110 mM KCl,10 mM HEPES, pH 7 and 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7 external and internal solution respectively, at different voltages as indicated. The closed channel current level is indicated. (B) Single channel IV relationships for NavSp1p channels in an asymmetric buffer solution, 110 mM KCl,10 mM HEPES, pH 7 [K]o and 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH7 [Na]i external and internal solution, respectively.

In conclusion, we established a stable and functional cell-free expression system for NavSp1p. The yield (0.02 mg purified protein/mL extract) is comparable to other membrane proteins [10,11,13]. The ion channel is a homo tetramer with functional characteristic resembling the protein expressed in E. coli [32]. This adds another functional membrane protein to the list of targets that can be produced by in vitro expression [10] and also to the list of in vitro expressed sodium channels, coming two decades after expression of a mechanosensitive renal Nav [43] as the first from the family of bacterial voltage-gated Navs. The expression system can be adopted for efficient site-specific incorporation of isotope labeled amino acid, enabling the bio-spectroscopic investigation of this ion channel protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Daniel Minor for the donation of the plasmids for NavSp1p and HRV 3C protease. This work was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council, and the European Research Council through agreement number 279944.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: Navs, voltage-gated sodium channels; NavSp1p, sodium channel from Silicibacter pomeroyi; CMC, critical micelle concentration; GUVs, giant unilamellar vesicles.

Contributor Information

Sebastian Peuker, Email: peukers@gmail.com.

Sebastian Westenhoff, Email: westenho@chem.gu.se.

References

- 1.Hille B. Ion Channels Excit. Membr. Sinauer Associates, Inc.; Sunderland, MA: 2001. pp. 1–22. http://pub.ist.ac.at/Pubs/courses.migrated/2012/introductiontoneuroscience1/docs/Lectures May 13,15/Hille_Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes_Chapter1.pdf (accessed March 16, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall W.A. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall W.A. Voltage-dependent gating of sodium channels: correlating structure and function. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren D., Navarro B., Xu H., Yue L., Shi Q., Clapham D.E. A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science. 2001;294:2372–2375. doi: 10.1126/science.1065635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Zheng N., Catterall W.A. The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2011;475:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCusker E.C., D’Avanzo N., Nichols C.G., Wallace B.a. Simplified bacterial “pore” channel provides insight into the assembly, stability, and structure of sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16386–16391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.228122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle D.A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R.A., Kuo A., Gulbis J.M., Cohen S.L. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9525859 (accessed March 11, 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köpfer D.A., Song C., Gruene T., Sheldrick G.M., Zachariae U., de Groot B.L. Ion permeation in K+ channels occurs by direct Coulomb knock-on. Science. 2014;346:352–355. doi: 10.1126/science.1254840. (80-.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noskov S.Y., Bernèche S., Roux B. Control of ion selectivity in potassium channels by electrostatic and dynamic properties of carbonyl ligands. Nature. 2004;431:830–834. doi: 10.1038/nature02943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaksson L., Enberg J., Neutze R., Göran Karlsson B., Pedersen A. Expression screening of membrane proteins with cell-free protein synthesis. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012;82:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonar S., Patel N., Fischer W., Rothschild K.J. Cell-free synthesis, functional refolding, and spectroscopic characterization of bacteriorhodopsin, an integral membrane protein. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13777–13781. doi: 10.1021/bi00213a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goren M.A., Fox B.G. Wheat germ cell-free translation, purification, and assembly of a functional human stearoyl-CoA desaturase complex. Protein Expr. Purif. 2008;62:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deniaud A., Liguori L., Blesneac I., Lenormand J.L., Pebay-Peyroula E. Crystallization of the membrane protein hVDAC1 produced in cell-free system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:1540–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernhard F., Tozawa Y. Cell-free expression–making a mark. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klammt C., Schwarz D., Löhr F., Schneider B., Dötsch V., Bernhard F. Cell-free expression as an emerging technique for the large scale production of integral membrane protein. FEBS J. 2006;273:4141–4153. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spirin A.S. High-throughput cell-free systems for synthesis of functionally active proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarecki B.W., Makino S., Beebe E.T., Fox B.G., Chanda B. Function of Shaker potassium channels produced by cell-free translation upon injection into Xenopus oocytes. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1040. doi: 10.1038/srep01040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falk M.M., Buehler L.K., Kumar N.M., Gilula N.B. Cell-free synthesis and assembly of connexins into functional gap junction membrane channels. EMBO J. 1997;16:2703–2716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyford L.K. Cell-free expression and functional reconstitution of homo-oligomeric alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors into planar lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25675–25681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tegler L.T., Corin K., Hillger J., Wassie B., Yu Y., Zhang S. Cell-free expression, purification, and ligand-binding analysis of Drosophila melanogaster olfactory receptors DmOR67a, DmOR85b and DmORCO. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:7867. doi: 10.1038/srep07867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg R.L., East J.E. Cell-free expression of functional Shaker potassium channels. Nature. 1992;360:166–169. doi: 10.1038/360166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dondapati S.K., Kreir M., Quast R.B., Wüstenhagen D.A., Brüggemann A., Fertig N. Membrane assembly of the functional KcsA potassium channel in a vesicle-based eukaryotic cell-free translation system. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014;59:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awayda M.S., Ismailov I.I., Berdiev B.K., Benos D.J. A cloned renal epithelial Na+ channel protein displays stretch activation in planar lipid bilayers. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:C1450–C1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.6.C1450. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7611365 (accessed February 23, 2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kigawa T., Yabuki T., Yoshida Y., Tsutsui M., Ito Y., Shibata T. Cell-free production and stable-isotope labeling of milligram quantities of proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999;442:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01620-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9923595 (accessed December 28, 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.C.R. Baiz, M. Reppert, A. Tokmakoff, Introduction to protein 2D IR Spectroscopy, (2012) 1–38.

- 26.Woutersen S., Mu Y., Stock G., Hamm P. Hydrogen-bond lifetime measured by time-resolved 2D-IR spectroscopy: N-methylacetamide in methanol. Chem. Phys. 2001;266:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganim Z., Tokmakoff A., Vaziri A. Vibrational excitons in ionophores: experimental probes for quantum coherence-assisted ion transport and selectivity in ion channels. New J. Phys. 2011;13:113030. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang C., Hochstrasser R.M. Two-dimensional infrared spectra of the 13C=18O isotopomers of alanine residues in an alpha-helix. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:18652–18663. doi: 10.1021/jp052525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye S., Zaitseva E., Caltabiano G., Schertler G.F.X., Sakmar T.P., Deupi X. Tracking G-protein-coupled receptor activation using genetically encoded infrared probes. Nature. 2010;464:1386–1389. doi: 10.1038/nature08948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noren C.J., Anthony-Cahill S.J., Griffith M.C., Schultz P.G. A general method for site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins. Science. 1989;244:182–188. doi: 10.1126/science.2649980. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2649980 (accessed October 28, 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loscha K.V., Herlt A.J., Qi R., Huber T., Ozawa K., Otting G. Multiple-site labeling of proteins with unnatural amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:2243–2246. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaya D., Kreir M., Robbins R.a., Wong S., Hammon J., Brüggemann A. Voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV) protein dissection creates a set of functional pore-only proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106811108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen A., Hellberg K., Enberg J., Karlsson B.G. Rational improvement of cell-free protein synthesis. N. Biotechnol. 2011;28:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2010.06.015. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1871678410004917 (accessed January 20, 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.S. Peuker, H. Andersson, K.S. Maiti, S. Niebling, A. Pedersen, M. Erdelyi et al., Isotope-edited proteins for site-directed infrared spectroscopy, Submitted (n.d.), (in preparation). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Grodberg J., Dunn J.J. OmpT encodes the Escherichia coli outer membrane protease that cleaves T7 RNA polymerase during purification. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1245–1253. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1245-1253.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davanloo P., Rosenberg A.H., Dunn J.J., Studier F.W. Cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:2035–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2035. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=345431&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed December 16, 2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreir M., Farre C., Beckler M., George M., Fertig N. Rapid screening of membrane protein activity: electrophysiological analysis of OmpF reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Lab Chip. 2008;8:587–595. doi: 10.1039/b713982a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gassmann O., Kreir M., Ambrosi C., Pranskevich J., Oshima A., Röling C. The M34A mutant of Connexin26 reveals active conductance states in pore-suspending membranes. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;168:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D’Avanzo N., McCusker E.C., Powl A.M., Miles A.J., Nichols C.G., Wallace B.A. Differential lipid dependence of the function of bacterial sodium channels. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yue L., Navarro B., Ren D., Ramos A., Clapham D.E. The cation selectivity filter of the bacterial sodium channel, NaChBac. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;120:845–853. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028699. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2229573&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed December 07, 2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarz D., Klammt C., Koglin A., Löhr F., Schneider B., Dötsch V. Preparative scale cell-free expression systems: new tools for the large scale preparation of integral membrane proteins for functional and structural studies. Methods. 2007;41:355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.F. Siebert, P. Hildebrandt, Vibrational Spectroscopy in Life Science, 2008.

- 43.I. Ismailov, K. Berdiev, D.J. Benos, A cloned renal epithelial Na+ channel protein displays stretch activation in planar lipid bilayers, (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]